Abstract

This conceptual paper introduces the Integrated Transformative Potential Intervention Development (InTrePID) Method. InTrePID is a method that social problem solvers can use to develop interventions (practices, programs, policies, culture) that translate the critical transformative potential development framework into concrete practice steps: (1) dialogue, (2) critical participatory action research initiatives, (3) skill building, and (4) critical action project implementation. The purpose of the InTrePID method is to develop each prong of the Critical Transformative Potential Development Framework: consciousness (awareness), accountability/responsibility, efficacy (ability), and action. The framework is theorized to bridge the gap between critical consciousness and critical action needed to transform and address dehumanizing realities that harm the self, relationships, and the community. In essence, InTrePID should generate a cyclical process for participants to increase awareness of individual and systemic factors that perpetuate interpersonal and community violence; take responsibility for (in)actions that perpetuate dehumanization and accountability for implementing solutions; develop efficacy in individual and collective community/cultural organizing skills; and, practice solution-oriented multi-level action. The paper highlights the work of a community-based project as an example of one way to implement the method to support community members in healing from the harm of dehumanization by addressing the violence of living in a dehumanizing society.

1. Introduction

This paper introduces and reflects on the Integrated Transformative Potential Intervention Development (InTrePID) Method for healing, equity, innovation, and reconciliation through personal, relational, and community transformation. To demonstrate a community-based project’s implementation of each prong of the method in practice, this paper highlights the work of the HOW project. “HOW” stands for “hate/heal our women.” The name of the project was derived from the Tupac song, “Keep Ya Head Up” that asks “…do we hate our women?” and then states “…Time to heal our women” (Shakur et al. 1993). The InTrePID Method was developed from and to support the HOW project’s credible messengers in their work to raise critical awareness of and action against community violence, specifically sexual and gender-based violence; to develop individual and communal potential to transform self, relationships and community; and, to increase safety to be one’s authentic self. As the lead on the project, I developed methods and strategies that could generate the desired outcome—participants developing and sustaining critical awareness of and critical action against dehumanizing/oppressive realities—the highest levels of Critical Transformative Potential. For the purposes of this paper, “critical” means a socio-structural understanding that connects macro-level processes with micro-level consequences. I also created the Critical Transformative Potential Development Framework (Jemal and Bussey 2018) to bridge the gap between critical consciousness and critical action—to realize and facilitate the potential to transform consciousness into action. The framework became a four-prong model that includes awareness, accountability, ability, and action. Through the collective journey of exploring ways to convert the abstract framework into practice during implementation of the HOW project, a new process emerged that incorporated critical dialogue, critical participatory action research (CPAR) initiatives, skill-building, and community and/or cultural organizing. The HOW project put this thought experiment into practice and, after informally noting the strengths and impact of the process, it became the InTrePID Method (see Table 1). The method operates on at least two levels: (1) it is a method to develop socio-cultural interventions (programs, policies, practices) grounded in the Critical Transformative Potential Development Framework for personal and social transformation of dehumanizing/oppressive realities; and (2) the participation in the process of developing the intervention that attacks dehumanization is, itself, a healing intervention for the effects of dehumanization.

Table 1.

From Transformative Potential to the InTrePID Method.

2. Part I: Critical Consciousness for Healing and Liberation

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. (King 1958), recognizing the interplay of social injustice processes and outcomes, stated, “There must be a rhythmic alteration between attacking the causes and healing the effects”. In other words, attacking the causes of a social issue (e.g., racial disparities in life, liberty and justice), not only prevents effects by eliminating the causes (e.g., racialized dehumanization), but also works to heal the effects—as the process of addressing the causes is a healing process in and of itself. Attacking the causes is healing work and healing works to attack the causes. In this respect, the healing from transformation of self, relationships, and communities, cannot occur if underlying social and systemic forces (the causes) are not acknowledged, analyzed, and addressed. As such, critical consciousness—and its derivative, Transformative Potential—with a focus on upending the dehumanizing -isms (e.g., racism, sexism, heterosexism) has been identified as essential to healing from oppressive violence and trauma (Jemal 2018; Watts et al. 2011).

The –isms flourish and spread in societies that lack critical consciousness (Freire [1970] 2000). Each social identity has its respective form of inequity: racism, sexism, heterosexism, classism, etc. These –isms, as ideologies of dominance, inform micro to macro processes that produce violent consequences for individuals and communities (Dunlap and Johnson 1992). The –isms use many tools and methods to dehumanize the masses and maintain the sociopolitical hierarchy of power. One method is cultural invasion (Freire [1970] 2000). “In this phenomenon, the invaders penetrate the cultural context of another group, in disrespect of the latter’s potentialities; they impose their own view of the world upon those they invade and inhibit the creativity of the invaded by curbing their expression” (Freire [1970] 2000). Freire ([1970] 2000) noted that cultural invasion is always an act of violence against the persons belonging to the invaded culture who lose or risk losing their originality. “Cultural invasion, which serves the ends of conquest and the preservation of oppression, always involves a parochial view of reality, a static perception of the world, and the imposition of one world view upon another. It implies the “superiority” of the invader and the “inferiority” of those who are invaded, as well as the imposition of values by the former, who possess the latter and are afraid of losing them” (Freire [1970] 2000). As such, “[c]ultural invasion is on the one hand an instrument of domination, and on the other, the result of domination” (Freire [1970] 2000). The –isms are a process of dehumanization and, simultaneously, the outcome of dehumanization. The –isms, as process and outcome, are cyclical and self-perpetuating. Likened to a virus, they weaken a society by attacking its own people. No one is immune to the consequences of daily living in a dehumanizing society. The constant attacks on human beings simply for being human creates mutated beings disconnected from their humanity (Freire [1970] 2000). When infected with dehumanizing realities, our humanity is negatively affected by dehumanizing effects; but fortunately, scholars have identified critical consciousness as the antidote (Jemal 2018; Watts et al. 2011).

The goal of critical consciousness is liberation (Freire [1970] 2000). Liberation requires individuals to repossess their humanity through “praxis: reflection and action upon the world in order to transform it” (Freire [1970] 2000, p. 51). Developing critical consciousness—awareness of and action against oppressive realities—is a way to reclaim our humanity (Freire [1970] 2000). When we reclaim our humanity, we re-member ourselves, reuniting pieces of our identities that have been forgotten or damaged by the –isms. Thus, the development of critical consciousness both attacks the causes (the –isms) and causes healing effects (humanization). As such, a key aspect of critical consciousness development is that people move from being objects that are acted upon by oppressive conditions to empowered subjects that act upon their sociopolitical environment for justice (Diemer et al. 2006; Freire [1970] 2000). Freire used a process to move individuals through a series of lower, non-critical levels or stages of consciousness to higher levels of consciousness (Campbell and MacPhail 2002; Carlson et al. 2006; Freire 1973). For action, the solution is not to adapt to structures of oppression, but to transform those structures to support the humanization of all beings (Freire [1970] 2000).

To date, there has been significant innovative scholarship around, and reformulation of, critical consciousness development as a way to ameliorate inequitable conditions and processes (Baxamusa 2008; Peterson 2014). The objective of critical consciousness is to shift causal attributions of social problem causes away from personal failings and toward structural faults (Diemer et al. 2017; Jemal 2017a). Through this shift, critical consciousness addresses multi-level (i.e., personal, communal, societal levels) and systemic (i.e., housing, employment, criminal justice systems) inequity (Freire [1970] 2000). As a result, critical consciousness has been used in research to examine a broad range of health, social, and educational disparities (Campbell and MacPhail 2002; Jemal et al. 2019a, 2020b; McGirr and Sullivan 2017; Windsor et al. 2014a) and is associated with a host of desirable individual-level outcomes among marginalized people (Chronister and McWhirter 2006; Diemer and Blustein 2006; Diemer and Li 2011; Hatcher et al. 2010; Seider et al. 2017). Thus, the construct of critical consciousness has important scholarly, practice, and policy implications. While scholars have noted the relevance and application of critical consciousness to current socio-behavioral health problems and have advanced its theory and practice, they have also identified conceptual and practice-based limitations (Jemal 2017a; Jemal 2018; Jemal and Bussey 2018).

Limitations of Critical Consciousness

Some scholars have limited the focus of critical consciousness to oppressed or marginalized populations (Baker and Brookins 2014; Watts et al. 2011). Such limited definitions exclude individuals perpetrating and/or perpetuating oppression and may inadvertently support the false proposition that oppression is a problem solely for oppressed individuals to solve. Equally problematic is the failure to incorporate the concept of privilege. The majority of definitions limit critical consciousness to addressing oppression (Garcia et al. 2009); however, systemic inequity requires dividing people into binary groups— “us” versus “them”—and applying differential treatment based on group membership. This differential treatment greatly determines access to opportunities and resources (Speri 2017). Thus, privilege and oppression are mutually reinforcing and operate in a cyclical process.

Transformative Potential, informed by the critical consciousness literature, developed in response to these limitations. Transformative Potential does not only apply to oppressed populations but also to the oppressor, the ally/ “accomplice,” and all those in between. Some social justice advocates have transitioned from using “ally” to “accomplice” to differentiate and indicate that an ally may stand with or be in support of a marginalized community, but an accomplice will act to dismantle the structures that oppress at the direction of the stakeholders in the marginalized group. Freire ([1970] 2000) stated, “The pedagogy of the oppressed is an instrument for their [the oppressed] critical discovery that both they and their oppressors are manifestations of dehumanization.” Transformative Potential adds the idea that the pedagogy of the oppressor is an instrument for their critical discovery that both they and the oppressed are manifestations of dehumanization. Critical Transformative Potential (i.e., the highest level of Transformative Potential) development is integral for members of privileged groups who have greater access to resources and power, and may operate as allies/accomplices (Thomas et al. 2014). To achieve liberation, it is imperative that beneficiaries of inequitable resource distribution and access to opportunities recognize injustices and acquire the knowledge and skills needed for social change. Although marginalized populations may use action to cope with, heal from, and resist dehumanizing contexts (Hernandez et al. 2005; Windsor et al. 2014a), privileged individuals can use their privilege to protect marginalized persons from harm and disrupt the oppressive status quo. Liberation requires solidarity in which the oppressor takes a radical posture of empathy, “entering into the situation of those with whom one is solidary” (Freire [1970] 2000). The requisite radical empathy takes compassion, self-awareness and critical consciousness to identify the similarities that exist within our lives across differences, while also interrogating the inequities and injustices woven in the seams of the local contextual fabric (Bussey et al. 2020).

3. Part II: Transformative Potential

Transformative potential includes social analysis of both forms of inequity: oppression and privilege. Transformative potential incorporates intersectionality, recognizing most individuals are some composition of hero and tyrant. Most importantly, Transformative Potential acknowledges the interdependence of human existence, that the liberty and humanity of the oppressed is coupled with the liberty and humanity of the oppressor. After the Transformative Potential process, the person “who emerges is a new person, viable only as the oppressor-oppressed contradiction is superseded by the humanization of all people…: no longer oppressor nor longer oppressed, but human in the process of achieving freedom” (Freire [1970] 2000). Along these lines, the framework incorporates a developmental, eco-social systems approach (Bronfenbrenner 1994) to encompass the interrelationships of systems, meaning how micro practices reflect macro socio-political processes and vice versa. Socio-behavioral health interventions, policies, and practices that treat behaviors as if they exist in a micro vacuum - by solely focusing on the individual level—allow invisible, inequitable socio-structural factors to continue unchallenged (Jemal et al. 2019b; Windsor et al. 2016). The transformative potential approach bridges the micro-macro divide by examining systemic inequity in conjunction with internalized oppression and privilege, which has not been addressed in the critical consciousness literature.

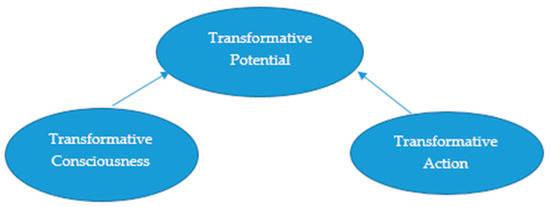

Transformative Potential constitutes levels of consciousness and action that produce potential to transform the contextual factors that perpetuate inequitable conditions and unjust outcomes at one or more socio-eco-systemic (e.g., individual or institutional) levels (Jemal 2017a, 2017b). Transformative Potential balances individual need and the need for social reform. In theory, a person with a high or critical level of Transformative Potential is more likely to critically reflect on inequitable conditions and actively work to produce equitable change. Transformation (of one’s self, relationships, or community) requires the simultaneous processes of reflecting and acting (Freire [1970] 2000). Merely reflecting on realities without intervention will not lead to transformation; and, moreover, one cannot truly perceive the depth of the problem without being involved in some form of action to confront it (Freire [1970] 2000). Thus, Transformative Potential is comprised of two dimensions: Transformative consciousness and transformative action (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The Transformative Potential Model. Note. Figure 1 depicts the two dimensions of Transformative Potential (Jemal 2018).

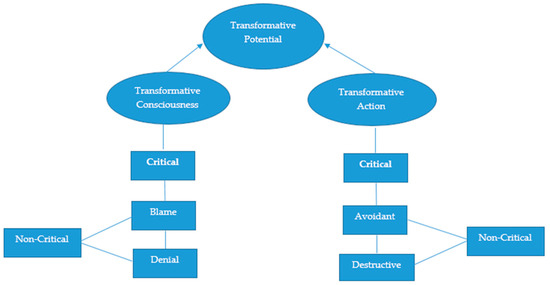

Transformative consciousness refers to the degree of awareness of systemic, institutional, and historical forces that promote and limit opportunities for specific groups within one or more socio-ecosystem (e.g., microsystem, macrosystem). Transformative consciousness acts as a lens for understanding how people are impacted by structural and historical oppression and includes three hierarchical levels—denial, blame, and critical (Jemal 2018). Transformative action is defined as individual and community action to dismantle inequity (i.e., privilege and oppression) at one or more levels of the socio-ecosystem (Jemal and Bussey 2018). Transformative action also has three tiered levels—destructive, avoidant, and critical (see Figure 2). Since inequity is inherently part of the culture, following the status quo through avoidant action is a path of violence and oppression. Thus, Transformative Potential interventions are important for moving bystanders or allies from avoidant to critical action.

Figure 2.

Levels of Transformative Consciousness and Transformative Action. Note. Figure 2 depicts the two dimensions of Transformative Potential with the levels of the Transformative Consciousness and Transformative Action dimensions (Jemal 2018).

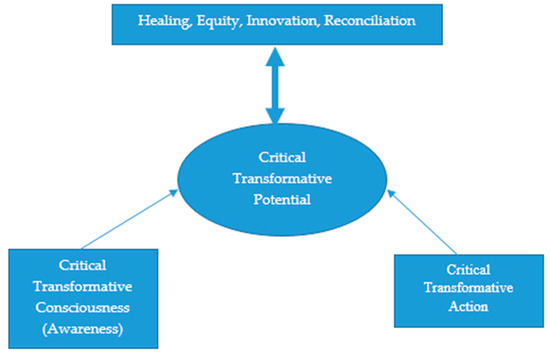

3.1. Critical Transformative Potential

Both dimensions (transformative consciousness and transformative action) determine one’s level of Transformative Potential, indicating how likely one is to transform (from personal to environmental transformation): that is, to be transformed and to transform (facilitate the transformation of others and/or transform their environment). The goal is for participants to progress from lower levels of transformative consciousness and action to critical transformative consciousness and action, thereby developing Critical Transformative Potential (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The Critical Transformative Potential Model. Note. Figure 3 depicts the two dimensions of Critical Transformative Potential.

Since both dimensions of Transformative Potential have hierarchical levels, Transformative Potential can be critical (made up of critical transformative consciousness and critical transformative action) or non-critical (in which transformative consciousness is blame or denial and transformative action is avoidant or destructive). Critical Transformative Potential, the highest level of Transformative Potential, is about information, interrogation, inspiration, imagination, innovation, and intervention, all of which begin with “I.” Likewise, the first step in developing Critical Transformative Potential begins with the self (“I”) as the subject for action: self-awareness and self-work to examine and address one’s own internalized privilege, oppression, prejudices, biases, and discriminatory behavior. However, even with self transformational work, the relationship between critical consciousness and critical action is murky (Jemal 2017a). Critical transformative consciousness does not ensure engagement in critical action (Watts et al. 2011). Perhaps critical action could lead one to develop critical consciousness, but it may be unlikely for people to engage in critical action without some level of critical understanding of systemic causal factors to formulate critical action responses. To bridge this divide, the Critical Transformative Potential Development Framework incorporates accountability/responsibility and efficacy. This framework makes it more likely for Critical Transformative Potential to manifest.

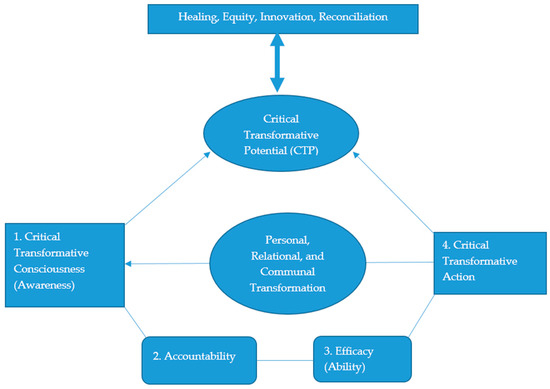

3.2. Critical Transformative Potential Development Framework

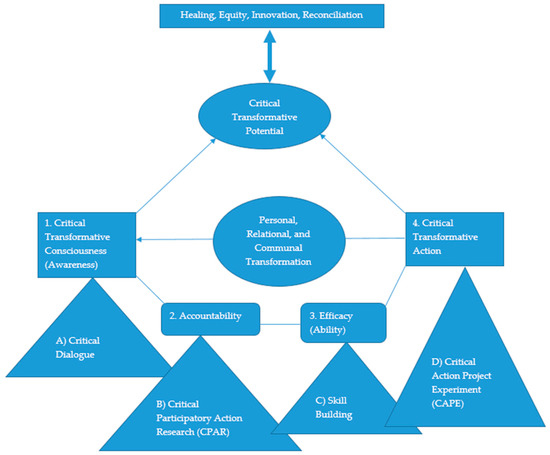

Scholars have noted that critical consciousness does not necessarily translate to critical action (Watts et al. 2011). The framework bridges the gap between consciousness and action, the two dimensions of the Critical Transformative Potential model. Critical Transformative Potential positions people to be “transformers” who make meaningful change in themselves, relationships, communities, and/or sociopolitical realities. People will be much more likely to engage in critical action if they consciously identify an issue, understand its structural linkages, and perceive the ability to create meaningful change via their actions (Watts et al. 2011). Built from this logic, the four pathways of the framework—critical consciousness (awareness), accountability/responsibility, efficacy (ability), and action—are pathways that enable people to develop the potential to transform. (see Figure 4). In practice, developing transformative potential is not linear; and development can occur simultaneously or sequentially along the pathways, such that focusing on one pathway (e.g., awareness) will develop another pathway (e.g., accountability). Moreover, one does not have to move through the pathways in a specific order. The framework is hypothesized to be multi-directional in that development of one pathway leads to development of other pathways or, in Freirian (Freire [1970] 2000) terms, “praxis”.

Figure 4.

Critical Transformative Potential Development Framework. Note. Figure 4 depicts the four pathways (numbers 1–4) of the Critical Transformative Potential Development Framework (Bussey et al. 2020). Critical Transformative Potential is the proposed outcome from the process of Critical Transformative Potential Development.

Freire noted that the liberation process cannot be a purely intellectual endeavor but must involve action, nor can the liberation process be limited to activism without serious reflection: ‘‘only then will it be a praxis’’ (Freire [1970] 2000). Praxis is ‘‘a continually evolving process’’ (Garcia et al. 2009) that ‘‘brings with it the possibility of a new praxis, which at the same time makes possible new forms of consciousness’’ (Hernandez et al. 2005) and action. The framework is consistent with Freirian pedagogy, in that social action should naturally loop back to analysis and dialogue that sustain change efforts — the foundation for liberation (Jemal 2017a). To structure this potentially challenging, transformative process, a template or method could be useful to those working to create trauma-informed and healing-centered practices, policies, opportunities and/or spaces in their lives, the lives of others or communities.

3.3. The InTrePID Method

There are numerous ways to develop interventions, or Critical Transformative Potential, or interventions that develop Critical Transformative Potential; one of which is the Integrated Transformative Potential Intervention Development (InTrePID) Method. In other words, InTrePID is a method or strategy for developing Critical Transformative Potential as well as a method to develop Critical Transformative Potential interventions. InTrePID implements the four pathways of Critical Transformative Potential Development. It is an interdisciplinary and multimodal method, as it draws on multiple professional fields’ perspectives and uses more than one method of intervention. Aligning with the four-pronged process of Critical Transformative Potential Development (awareness, accountability, ability and action), InTrePID has four components: (a) dialogue, (b) critical participatory action research initiatives, (c) cultural and community organizing skill building, and (d) critical action project experiments (CAPE) (see Figure 5). InTrePID’s four-component structure allows freedom and flexibility within the method. It creates a balance between allowing all possibilities for developing Critical Transformative Potential and having a rigid structure wherein all content and decisions are predetermined.

Figure 5.

The InTrePID Method to Develop Critical Transformative Potential for Healing, Equity, Innovation and Reconciliation. Note. Figure 5 depicts the full theoretical model consisting of Critical Transformative Potential, the Critical Transformative Potential Development Framework (numbers 1–4) with the components of the InTrePID method (letters A–D) theorized to promote personal, relational, and communal transformation for healing, equity, innovation, and reconciliation (Bussey et al. 2020).

4. Part III: The HOW Project—An Example of the InTrePID Method in Practice

This section presents a brief overview of each prong of the Critical Transformative Potential Development Framework using the HOW project as an example of each component of the InTrePID Method in practice. Although this paper introduces the components of the method, it does not provide models of practice for critical dialogue, critical participatory action research (CPAR), skill building, or critical action project experiments (CAPEs). This framework and the method are continuously evolving in tandem each time they are implemented as theory informs practice and practice informs theory. In fact, the four components were only identified as a cohesive method after implementation by the HOW project, and, in some respects, the framework emerged after informally considering how well the method worked in practice. This method integrates three areas—(1) Education, (2) Research, and (3) Cultural and Community Organizing Practice—to move toward humanizing transformation for those harmed by and/or for those who participate (intentionally or unconsciously) in structural, community, and/or interpersonal violence. For context, a brief description of the HOW project is provided; however, this paper is not a report on or study of the HOW project. The HOW project demonstrates one way to implement the InTrePID Method to develop each prong of the Critical Transformative Potential Framework.

The purpose of the HOW project was for participants to develop Critical Transformative Potential about racial and gender-based community violence. Black women disproportionately experience violence at home, school, work, and in their communities (Institute for Women’s Policy Research 2017). Black women face high rates of intimate partner violence (IPV), rape, and homicide (Institute for Women’s Policy Research 2017). Moreover, Black girls and women also experience institutionalized racism—they are disproportionately punished in school, funneled into the criminal justice system after surviving physical or sexual abuse, subjected to racial profiling and police brutality, and incarcerated at rates far exceeding their population percentage (Institute for Women’s Policy Research 2017). More than 4 in 10 Black women experience physical violence from an intimate partner during their lifetime (Institute for Women’s Policy Research 2017). Sexual violence and intimate partner violence, often resulting in death, affects Black women at disproportionate rates (Violence Policy Center 2020). When murdered by men, approximately nine of ten Black female victims knew their killers (Violence Policy Center 2020). Black women also experience significantly higher rates of psychological abuse—including humiliation, insults, name-calling, and coercive control—than do women overall (Women of Color Network 2006). Moreover, the lives of Black and LatinX transwomen are disproportionately affected by violence ranging from micro-aggressions to death (Human Rights Campaign 2020; Heffernan 2015).

Community violence, with a particular focus on sexual and/or gender-based violence, concerns power struggles and hierarchies that overlap multiple social constructs: race, gender, sexuality, and class. Intersecting socially-constructed identities make for real-life consequences and differences for those occupying these identities (Crenshaw 1989, 1991). The HOW project hoped that participants would realize, cope with, heal from, and transform personal, social, and systemic forces that permit and promote sexual and/or gender-based community violence. The project incorporated the creative arts to produce creativity and spontaneity for healing in action. Self-identified, African American (aged 18+) men (Group A) participated in discussions and trainings on oppression, violence, and research methods. These participants were identified as credible messengers because they belonged to the target community of young, Black males that had experienced community violence and were also part-time service providers employed with the community-based organization that partnered with this project. The HOW project provided a forum for Group A participants to gain a better understanding of how racism, sexism, and heterosexism intersect to engender violence against women and gender expansive people of color.

4.1. Critical Dialogue

The InTrePID Method begins with critical dialogue; however, there are two pre-dialogue steps that help to set the stage for critical, productive, and effective dialogue. The first dialogue preparatory step is to build sociometry. Sociometry, from psychodrama and sociodrama practice, entails making invisible connections between people visible (Moreno 1953). As humans, we are more alike than we are different, but we have been socialized to scrutinize and magnify our differences (a key feature of the divide and conquer tactics for creating, sustaining, and expanding inequity) and ignore the many ways in which we are similar and connected. Sociometry makes connections at the basic level of humanity and what it means to live as a human being. Being hurt in relationship is part of the human experience, and having the tools to heal our psycho-emotional wounds within relationship is also a uniquely human practice. Moreover, support for healing from trauma does not have to come from the same relationship that caused the injury. Healing lives in community in that healing takes place when in community. In community, each person is the healing agent for the other (Moreno 1953).

Building sociometry is critical for successful dialogue that interrogates inequity because the core of inequity is dehumanizing thought and action for person(s) harmed and for person(s) committing harm (Jemal et al. 2019c). As the sociometric connections develop in the group, radical empathy increases and improves the likelihood of open-minded listening. Open-minded listening is listening to hear the person rather than listening to hear yourself and for information that validates your points or confirms your beliefs (Cohen 2014). Open-minded listening also includes a willingness to change your mind or question deeply held beliefs (Cohen 2014). The sociometric connections with radical empathy and open-minded listening create an environment in which people are better able to work together, learn from each other, and use the healing power of relationship for transformation. Using relationship-building tools to create and highlight existing connections creates a brave and safer space for critical dialogue that is conducive to learning and growing together in a way that supports every participant’s humanity. A “safer” space is cultivated because no space can be guaranteed 100% psychologically or emotionally safe. These tools only help to make the space safer than it would be without the tools. Then, participants can hear and identify with another person’s narrative of when their humanity had been contested, even though each individual’s humanity may not have been contested in the same way (Sólorzano and Yosso 2002).

The second dialogue preparatory step is to conduct a healing circle. Healing circles can be an important component of restorative justice practice when working from the premise that hurt people hurt others, hurt themselves, and are hurting; and that there is not always a clear distinction between victim and offender (Hopkins 2002; Jemal et al. 2019c). Critical dialogue can be uncomfortable (Watt 2007). In general, people dislike discomfort and may either shut down/withdraw or lash out. These responses cause more hurt. Thus, it is important to start from a place of restoration that comes from telling your story before an audience that is there (fully present) to listen. For inequity and subsequent division to exist, lies have been told and people deceived to protect the oppressive status quo (Freire, 2000). The witnessing allows that person to be defined in and on their own terms, seen through their own words, and heard in their own voice (Sólorzano and Yosso 2002). As more narratives are shared, commonalities are discovered that may reduce feelings of isolation and thoughts like, “I’m the only one in this kind of situation,” or “It must be (something wrong with) me.” As transformative consciousness develops, questions transition from: “What’s wrong with you?” (the oppressive question) versus “What happened to you?” (the trauma-informed question) or “What do you need to support your humanity in this moment?” (the healing-centered question). Then, most importantly, the discussion shifts from analyzing and shaming “problematic” individuals to focusing on marginalizing systems and problematic cultural norms and values (Ortega-Williams et al. 2018).

Another purpose of critical dialogue is to identify a person’s level of transformative consciousness and to begin facilitating the process of progressing from a non-critical level to the critical level of transformative consciousness (Brown et al. 2016). Critical transformative consciousness development incorporates material from the humanities, for example, history, anthropology and American Studies disciplines. A socio-historical perspective is crucial because reality is contextual and present-day situations cannot be disconnected from yesterday’s events. Critical transformative consciousness breaks down the barriers of siloed knowledge and draws connections between past, present, and future; the socio-ecosystems, with awareness of how macro processes influence micro consequences; and, inequities based on singular social identities (e.g., racism, sexism, etc.). Critical dialogue interrogates power and its relationship to violence, the multi-systemic factors and causes of inequity that go beyond an individual’s behavior to question context and environment. Reflection and questions guide an assessment of the multi-level and multi-systemic factors, attributions, and historical knowledge about how intersecting systems and socio-structural forces create and sustain inequity over time. In the HOW project, to investigate gender-based violence using critical dialogue, the group analyzed the lyrics of Tupac’s song, “Keep Ya Head Up” (Shakur et al. 1993). The group explored the intersection of racism, heterosexism, and sexism in the lives of African American/Black males that create destructive patterns of relating to self, others, and community. Critical dialogue also incorporated slam poetry by artists with varying gender identities about sexuality, masculinity, femininity, power, and violence.

4.2. Critical Participatory Action Research (CPAR)

CPAR is used to begin to fill gaps in awareness and knowledge and answer questions that originated during the critical dialogue. Rooted in critical and liberation psychology, CPAR actively challenges ideas about who can conduct research and inequitable access to the knowledge produced by research (Stoudt et al. 2012). Participatory research is conducted by and for people with lived experience and/or most intimately affected by the issues the research addresses (Baum et al. 2006). The practice brings together distinct forms of personal and professional wisdom, academic knowledge, and lived experience “to study theoretically, empirically and politically, the structures and dynamics of injustice” (Stoudt et al. 2012). CPAR initiatives are used for the accountability/responsibility prong of the InTrePID Method because CPAR investigates the causal location or “root” of the issue, identifies sources of power, and interrogates beliefs, behaviors, and the culture perpetuating the identified problem. For the HOW project, the identified problem was sexual and gender-based violence against transgender and cisgender women of color. Critical participatory action research also investigates understandings of who has the most power and responsibility for working to create a just society (Baum et al. 2006); thereby, helping participants imagine their role in finding and initiating solutions.

The HOW project implemented parts of a CPAR project. The results of that project are not presented here, but may be forthcoming in a separate publication. Here, I provide a brief overview of the InTrePID Method’s CPAR project as executed by the HOW project. The CPAR portion of the HOW project included seven, three-hour training sessions. Through trainings on CPAR methods, the credible messengers developed a skill set for conducting research and obtaining information on important issues and prospective solutions or methods that could be used to address the issues most relevant to and congruent with the community’s needs. The first session provided an introduction to research. Session two introduced data collection methods. Participants gained familiarity with collecting data using focus groups, semi-structured interviews, and the Photovoice methodology. Session three was dedicated to certification for research with human subjects. All participants became certified in human subjects research. Session four developed data collection tools. Session five focused on data analysis. Session six was group facilitation training. In the last session, participants practiced obtaining informed consent and facilitating group discussions, similar to the critical dialogue session in which they participated a few weeks earlier.

4.2.1. A Discussion Groups

To execute the CPAR prong of the InTrePID Method, Group A, composed of credible messengers, decided to have discussion groups with members from their peer network (Group B) rather than focus groups for research purposes. Even though Group A elected to facilitate a critical dialogue for personal, interpersonal, and community development and not for “research” purposes in the academic sense, they obtained informed consent from participants to participate in the discussion. In short, Group A, the credible messengers, co-facilitated discussion groups with other participants from the community-based organization’s client population (Group B) to discuss sexual and gender-based community violence and the intersection of racism, heterosexism, and sexism in the lives of African American/Black males that create destructive patterns of relating to self, others, and community. Discussions explored how contemporary interactions are manifestations of historical oppression and trauma. The credible messengers used the knowledge gained from the discussions to inform their community organizing efforts (e.g., planning the community forum) to reduce gender-based community violence.

4.2.2. B Community Forum

Persons that participated in the project and community members were invited to attend a community forum in which Group A shared what they learned from this process, informed the community, and disseminated their work. The community forum was grounded in a restorative justice approach and liberation health model (Belkin Martinez 2014; Kant 2015). Discussions explored whether and how contemporary interactions between Black men and women are rooted in racism, sexism, and historical trauma, and if oppressive ways of thinking and acting are manifested in current personal, social, and community relationships. The community forum was structured to empower participants to think of action or intervention steps toward a cultural shift, rather than focusing on individual behavioral change by the person who was violated. For example, discussion questions asked participants to identify ways to intervene that go beyond teaching women self-defense, or advising women to walk in packs or not to venture out at a certain time of night. The introductory presentation included a video about gender-based violence created and produced by young people from another community-based organization.

After the introductory presentation, all participants joined in the community forum’s World Café. The World Café (The World Café 2015) created an environment to connect multiple ideas and perspectives on a topic by engaging participants in several rounds of small-group conversation. Participants that attended the community forum sat at a table with eight available seats. Each table had the same list of questions that pertained to ideas that originated in the discussion groups about sexual and gender-based violence. The small groups participated in three 20-minute rounds of conversation answering the questions. Tables were covered in butcher block paper for taking notes and doodles. At the end of the twenty minutes, each member of the group moved to another table to meet a new group of discussants. The World Café generated ideas for action and suggested sites for intervention that focused on dismantling inequity and redistributing power at the root and core of interpersonal and community violence. After the World Café, forum attendees participated in a healing circle.

4.3. Skill-Building

While many great ideas were generated from the World Café exercise, this work of social justice and social change depends on moving people from awareness to action. For some people, not knowing how to do or how to engage blocks their path from consciousness to action. “Know how” or skill development is the foundation of transformative efficacy. Creative methods can be used to learn and practice skills and develop efficacy by getting people unstuck. Creative methods facilitate creativity and spontaneity, leading to a radical imagining of alternative solutions and strategies. For example, improv theatre uses the “Yes and” method. Participants can practice saying “yes” to ideas and then adding on to improve the ideas, rather than discarding an idea for its negatives before exploring the positives. Particularly, sociodrama and Applied Theatre techniques are useful practices for the iterative process of generating ideas and putting ideas into action. They provide opportunities for behavioral rehearsal and role play so participants can play out ideas, test options, enact various scenarios in a safer environment, and receive feedback to effect better outcomes (Bussey et al. 2020). These techniques, and others, may help participants to develop the skills and comfort needed to take action in the real world. The HOW project incorporated skill-building exercises for credible messengers throughout the project, using role plays to practice facilitating group discussions and implementing data collection methods, and putting new skills into practice by organizing the community forum.

4.4. Critical Action Project

First, participants develop higher levels of awareness of systemic factors, hold themselves accountable for addressing the issue, and, cultivate efficacy. Then, they develop and execute a project to develop individual, interpersonal, community, and social Critical Transformative Potential. The purpose of the HOW project’s critical action project was to begin cultural and community organizing efforts to heal from and address the impact of historical oppression and trauma at the intrapersonal, interpersonal, and community levels that manifest in interpersonal violence and community harm (Ortega-Williams et al. 2018). For purposes of the InTrePID Method, it is important to note that the HOW project’s Community Forum could be categorized as a critical action project. The components of the InTrePID method overlap as noted in Figure 5, such that a critical action project can work in one (e.g., accountability) or more (e.g., awareness and ability) Critical Transformative Potential Development areas concurrently. Because the HOW project initially planned to continue working beyond the community forum, other project ideas were explored.

A main objective for the critical action project is for participants to reinvest in relationships and community. The HOW project participants discussed creating an ethnodrama theatrical piece informed by the discussion groups. Participants were searching for ways to connect lived experience from the CPAR component with the experimental visions from the community forum and skill-building activities for social transformation. Eventually, they selected an art gallery exhibition based on the information from the discussion groups and the World Café as a creative means to disseminate information from earlier phases of the project to the community. HOW project participants discussed selecting major themes extracted from the earlier phases of the project and visually depicting themes by community artists. This process is similar to one that was used to create the paintings for the Community Wise intervention (Windsor et al. 2014b) to spark critical dialogue among the participants (Jemal et al. 2020a; Windsor et al. 2014a). When exploring venues to display the themed-artwork, the group suggested using the site of a conference with related content, such as restorative justice, liberation-based healing, or anti-racism. Each painting would be displayed with a caption that included a quote from the discussion group and a written description from the artist about how the painting interprets that quote. However, because I ended the HOW project after the community forum, the plan to translate themes into artwork and select a venue to display the art was postponed indefinitely; hopefully, to be a critical action project for another time.

Freire ([1970] 2000) noted that critical consciousness development is a cyclical process that oscillates between reflection and action. This cyclical process or praxis is also evident in this work in that the project started with critical dialogues meant to raise participants’ critical consciousness. This raised awareness led participants to plan a community forum and think about an art gallery project that would be used to continue critical dialogue among those viewing the artwork at the conference. They also discussed having an impromptu or pop-up healing circle in the art gallery or at the conference. Although this idea did not come to fruition, one of the Group A participants individually took another critical transformative action step by enrolling in a Masters of Social Work (MSW) program. Joining formal education with lived experience is a powerful combination for raising Critical Transformative Potential and leading and initiating transformative efforts. By developing transformers to transform, a cyclical process is initiated between transformative individuals and environments that should produce profound insight and growth.

For project sustainability, grounding the critical action project component of the InTrePID Method within social enterprise is strategically valuable. “Social Enterprise” refers to various entrepreneurial strategies and activities that, when applied to community issues, support the public interest and redistribute economic and social resources to marginalized populations (Gray et al. 2003). For example, the social enterprise aspect of the HOW Project’s planned venture was that the artwork would constitute a silent auction to raise funds for the community-based partner organization to continue its work of social justice and healing from community violence and trauma. The critical action project should make an investment in the community so the work takes on a life of its own and continues to produce fertile ground for counter-activism. Ideally, the project facilitates empowerment at individual, collective, and systemic levels and initiates social change that can range in extensiveness from raising an individual’s Transformative Potential to beginning a social movement. The InTrePID Method may facilitate individuals’’ and communities’ potential to transform intention, power, and impact from harming to healing lives in community.

5. Implications and Future Considerations

This paper’s significance is grounded in its implications that bridge several divides in the critical consciousness literature and beyond; such as, consciousness and action; privilege and oppression; micro and macro; theory and practice. In the spirit of practice-based research and acknowledgment of the continual evolvement of the framework and the method, I added a fifth prong to the framework, “affinity/relationship-building,” that encapsulates the pre-dialogue components featured in the HOW project. Future research is needed to determine the InTrePID Method’s effectiveness at bridging divides and, most importantly, developing Critical Transformative Potential. For practitioner consideration, the inclusion of the creative arts may enhance InTrePID’s effectiveness. With moments of reflection, during and after HOW project implementation, it became evident that incorporating the creative arts strengthens the InTrePID method’s capacity to develop each prong of the Critical Transformative Potential Development Framework. The creative arts are helpful when confronting difficult and painful discussions, like those in which the HOW project participants engaged about violence against Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC) transwomen and cisgender women.

Freire ([1970] 2000) insinuates the importance of creativity and cultural organizing in the form of radical imagination. The struggle for liberation requires making the invisible, inequitable forces visible and perceiving the reality “of oppression not as a closed world from which there is no exit, but as a limiting situation which they can transform” (Freire [1970] 2000), rather than reform. Imagination and creativity tap into the unknown for transformative discoveries that explore tensions and dialectical relationships (Freire [1970] 2000)—that is, holding opposing perspectives simultaneously and/or performing contradictory behaviors (e.g., the principle that all men are created equal while supporting slavery). Working in the realm of culture against cultural invasion, the creative arts possess the power to spotlight invisible, underlying oppressive factors hiding in the backstage shadows of our psyches (e.g., implicit biases) (Griffith and Semlow 2020). Theatre and other art forms have the power to amplify the voices of the silenced and raise awareness of horrific and problematic events that people attempt to ignore. For example, theatre companies brought the inhumane act of lynching to center stage. Theatre dramas, primarily produced by Black women, brought to life knowledge gaps at the intersections of race, class, and gender, that decentered and deconstructed white supremacy, capitalism, and patriarchy (Perkins and Stephens 1998). Many lynchings of Black Americans demonstrated how unsupported accusations by White women against Black men were as serious as life or death (Wiegman 1993). The lynching dramas exposed the mentality that stereotyped Black men as rapists, Black women as prostitutes, and White women as the property of White men (Hill and Hatch 2003). With theatre, audiences were allowed to peek through the eyes of another to see a different, perhaps hidden, perspective. As such, the creative arts can become “‘the practice of freedom,’ the means by which men and women deal critically and creatively with reality and discover how to participate in the transformation of their world” (Freire [1970] 2000).

Examining knowledge gaps and pitfalls of current movements is important in the healing process, deepening our understanding of transforming self, relationships, and environment. Although started by a Black woman, Tarana Burke, the #MeToo Movement gained a national stage and spotlight when contesting White women as the property of White men and condemning the discounting of White women’s accusations of sexual violence. In contrast, the lynching dramas visually depicted the intersection of class, race, and gender, where women of color are left out on the corner, a blind spot of #MeToo when looking back in history. Artistic methods can facilitate consciousness and action about White women’s lack of responsiveness to the sexual violence against women of color. Theatre and other art forms that highlight intersectionality and center the voices of those with lived experience are essential tools for the development of Critical Transformative Potential.

Practitioners of the InTrePID Method can select an art form (e.g., dance, poetry, visual arts) as a tool to implement one or more components of the method that best meets their Critical Transformative Potential development needs. In selecting one or more art forms, practitioners should be aware that the nexus between the arts and social consciousness must include an adequate socio-cultural and historical background that explores the dialectics (that is, balancing intersecting, multi-dimensional conditions and narratives that may conflict and/or be in opposition) of human existence. As discovered in the HOW project, interventions that prevent or address sexual or gender-based community violence and its impending trauma must not be ahistorical or decontextualized. For these reasons, there is a great need for methods that infuse art and trauma-informed consciousness into healing-responsive action, manage the dialectics and socio-historical complexity.

InTrePID is a method to design specific interventions that translate the Critical Transformative Potential Development Framework into practice for all participants, including facilitators. A key implication and revelation from implementing InTrePID with the HOW project is that the process of developing an intervention that develops Critical Transformative Potential is, itself, an intervention that develops Critical Transformative Potential. Thus, by developing and facilitating the HOW project, I was pulled into my own Critical Transformative Potential Development as I worked to facilitate that process for the HOW participants. As such, creating and discovering this work has been a healing process for me. I engaged in critical dialogue raising my critical awareness. I discovered my accountability, developed individual and community capacity, and engaged in many critical action projects that have cycled me back to broadening my awareness of the impact of the –isms on me, my relationships and community. This work informs the next steps of my healing journey to become a trauma-informed and healing-centered educator, researcher, and practitioner.

To be transparent, I am still learning all that the method has to offer. In fact, I may never learn all that InTrePID has to teach me because, I believe, learning and healing are a lifelong journey. I am learning that Transformative Potential, as an inter- and multidisciplinary, intersectional, multi-level, and multi-systemic theoretical framework grounded in critical consciousness theory, prepares interventions to address symptoms (effects) and the viral roots (causes) which then generates radical imaginative practice, policies, and culture. I am learning that InTrePID is a method for intervention that, in and of itself, is a healing process and also produces healing possibilities. The InTrePID Method is theorized to be healing work on four levels. It is healing when: (1) using the InTrePID Method (the process) to develop socio-cultural interventions (practices, programs, policies); (2) implementing the intervention; (3) participating in the developed intervention; and (4) discovering possibilities for continuing the healing journey for self and others using the critical action projects. Although future research is needed to test the method, the theory suggests that a person with a high level of Transformative Potential critically reflects on the conditions that shape their life and actively works with their self and/or others to change problematic conditions (Jemal 2017a). The method assists practitioners, researchers, and educators to do their own trauma-informed, healing-centered work while facilitating this process for others. In my work, Critical Transformative Potential has bridged theory, research, education, and practice. Following this method has directed me, as an educator, to produce Masters of Social Work (MSW) curriculum to share the method; as a researcher, to pursue passion projects (CAPEs) that aim to address causes and heal effects; and, as a practitioner, to work with organizations, associations, and government agencies to produce healing practices, policies, and culture within their specific contexts. These examples demonstrate how InTrePID has put the Critical Transformative Potential Development Framework into practice in my life. Future research could test the framework to determine if and how well it transforms developing consciousness, imagination, passion, and potential into action for healing, equity, innovation, and reconciliation.

6. Conclusions

The purpose of this paper was to introduce the InTrePID method. InTrePID translates the abstract Critical Transformative Potential Development Framework into practice as exampled by the HOW project. The Framework is theorized to attack the causes and heal the effects of the -isms for those harmed and for those who perpetuate harm. I offer InTrePID as an approach to and for healing from daily living in a dehumanizing society. The –isms are both a process of dehumanization and a consequence of dehumanization. In other words, the –isms make and cause harm, in some cases, irreparable harm to individuals, relationships, and communities; but nonetheless, harm from which healing is a beneficial option. Critical Transformative Potential recognizes that the dehumanization is the pathology that results in actions, conditions, and states of being that are adaptive to dehumanization; but, maladaptive for liberation. Socio-health issues, like community and gender-based violence, are symptoms of an unhealthy society that has been infected by the –isms. Interventions that are not radical in their essence will miss the root cause of the issue and only treat the symptoms. Consequently, the –isms will continue unfettered to threaten life, liberty, justice, wellness, and all that is uniquely human. When any one is dehumanized, we are all dehumanized whether perpetrator, perpetuator, victim, and/or survivor. Being dehumanized, dehumanizing someone else, and allowing dehumanization to occur are all points on the dehumanization cycle. To stop this cycle, there is a need for humanizing work that is trauma-informed and healing centered. This work calls for an understanding that attacking the –isms is healing the effects; and healing the effects is attacking the –isms. This paper offers the InTrePID Method, in whole or in part, as a tool for researchers, educators, healing practitioners, community/cultural organizers, social workers, social entrepreneurs, survivors, and to all those who do or want to do the work of developing/implementing socio-cultural interventions (practices, programs, policies) at various levels (personal, relational, communal, societal) that attack causes for healing effects to reclaim our humanity and declare liberation.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Baker, Alison M., and Craig C. Brookins. 2014. Toward the development of a measure of sociopolitical consciousness: Listening to the voices of Salvadoran youth. Journal of Community Psychology 42: 1015–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, Fran, Colin MacDougall, and Danielle Smith. 2006. Glossary: Participatory action research. Journal of Epidemiol and Community Health 60: 854–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baxamusa, Murtaza H. 2008. Empowering communities through deliberation: The model of community benefits agreements. Journal of Planning Education and Research 27: 261–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkin Martinez, Dawn. 2014. The liberation health model. In Social Justice in Clinical Practice: A Liberation Health FRAMEWORK for Social Work. Edited by Dawn Belkin Martinez and Ann Fleck-Henderson. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 9–28. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, Urie. 1994. Ecological Models of Human Development. In International Encyclopedia of Education, 2nd ed. Oxford: Elsevier, vol. 3, Available online: http://www.psy.cmu.edu/~siegler/35bronfebrenner94.pdf (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Brown, Hilary, Richard D. Sawyer, and Joe Norris, eds. 2016. Forms of Practitioner Reflexivity: Critical, Conversational, and Arts-Based Approaches. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Bussey, Sarah, Alexis Jemal, and Sherika Caliste. 2020. Transforming social work’s potential in the field: A radical framework. Social Work Education. in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Catherine, and Catherine MacPhail. 2002. Peer education, gender and the development of critical consciousness: Participatory HIV prevention by South African youth. Social Science and Medicine 55: 331–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, Elizabeth D., Joan Engebretson, and Robert M. Chamberlain. 2006. Photovoice as a social process of critical consciousness. Qualitative Health Research 16: 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chronister, Krista M., and Ellen H. McWhirter. 2006. An experimental examination of two career interventions for battered women. Journal of Counseling Psychology 53: 151–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Jonathan R. 2014. Open-Minded Listening. 5 Charlotte L. Rev. 139. Available online: https://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1479&context=facultypub (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Crenshaw, Kimberlé. 1989. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum 1989: 139–67. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, Kimberlé. 1991. Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review 43: 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diemer, Matthew A., and David L. Blustein. 2006. Critical consciousness and career development among urban youth. Journal of Vocational Behavior 68: 220–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diemer, Matthew A., and Cheng Hsien Li. 2011. Critical consciousness development and political participation among marginalized youth. Child Development 82: 1815–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diemer, Matthew A., Aimee Kauffman, Nathan Koenig, Emily Trahan, and Chueh An Hsieh. 2006. Challenging racism, sexism, and social injustice: Support for urban adolescents’ critical consciousness development. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 12: 444–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diemer, Matthew A., Luke J. Rapa, Catalina J. Park, and Justin C. Perry. 2017. Development and validation of the critical consciousness scale. Youth & Society 49: 461–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, Eloise, and Bruce D. Johnson. 1992. The setting for the crack era: Macro forces, micro consequences. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 24: 307–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freire, Paulo. 2000. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Continuum. First published 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, Paulo. 1973. Education for Critical Consciousness. New York: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, Marisol, Iva Kosutic, Teresa McDowell, and Stephen A. Anderson. 2009. Raising critical consciousness in family therapy supervision. Journal of Feminist Family Therapy 21: 18–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, Mel, Karen Healy, and Penny Crofts. 2003. Social enterprise: Is it the business of social work? Australian Social Work 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, Derek M., and Andrea R. Semlow. 2020. Art, anti-racsim and health equity: “Don’t ask me why, ask me how!”. Ethnicity & Disease 30: 373–80. [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher, Abigail, Jacques de Wet, Christopher Philip Bonell, Vicki Strange, Godfrey Phetla, Paul M. Proynk, Julia C. Kim, Linda Morison, John D. H. Porter, Joanna Busza, and et al. 2010. Promoting critical consciousness and social mobilization in HIV/AIDS programmes: Lessons and curricular tools from a South African intervention. Health Education Research 26: 542–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heffernan, Dani. 2015. GLAAD Launches Trans Microaggressions Photo Project #transwk. Available online: https://www.glaad.org/blog/glaad-launches-trans-microaggressions-photo-project-transwk (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Hernandez, Pilar, Rhea Almeida, and Ken Dolan-Del. 2005. Critical consciousness accountability, and empowerment: Key processes for helping families heal. Family Process 44: 105–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, Errol C., and James V. Hatch. 2003. A History of African American Theatre. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, Belinda. 2002. Restorative justice in schools. Support for Learning 17: 144–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Human Rights Campaign. 2020. Fatal Violence against the Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming Community in 2020. Available online: https://www.hrc.org/resources/violence-against-the-trans-and-gender-non-conforming-community-in-2020 (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Institute for Women’s Policy Research. 2017. Violence against Black Women—May Types, Far-Reaching Effects; Washington: Institute for Women’s Policy Research. Available online: https://iwpr.org/iwpr-issues/race-ethnicity-gender-and-economy/violence-against-black-women-many-types-far-reaching-effects/ (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Jemal, Alexis. 2017a. Critical consciousness: A critique and critical analysis of the literature. Urban Review 49: 602–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jemal, Alexis. 2017b. The opposition. Journal of Progressive Human Services: Radical Thought and Practice (JPHS) 28: 134–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jemal, Alexis. 2018. Transformative consciousness of health inequities: Oppression is a virus and critical consciousness is the antidote. Journal of Human Rights and Social Work 3: 202–15. Available online: https://rdcu.be/2Cxm (accessed on 28 December 2020). [CrossRef]

- Jemal, Alexis, and Sarah Bussey. 2018. Transformative action: A theoretical framework for breaking new ground. EJournal of Public Affairs 7: 37–65. Available online: http://www.ejournalofpublicaffairs.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/211-1311-1-Galley.pdf (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Jemal, Alexis, Alana Gunn, and Christina Inyang. 2019a. Transforming responses: Exploring the treatment of substance-using African American women. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse 19: 659–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jemal, Alexis, Myrtho Gardiner, and Katharine Bloeser. 2019b. Perceived race as variable: Moderating relationship between perceived discrimination in workplace and mentally unhealthy days. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 6: 265–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jemal, Alexis, Sarah Bussey, and Briana Young. 2019c. Steps to racial reconciliation: A movement to bridge the racial divide and restore humanity. Social Work and Christianity 47: 31–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jemal, Alexis, Liliane Windsor, Christina Inyang, and Christina Pierre-Noel. 2020a. We need to talk: Critical dialogue development, process and implementation in group practice. under review. [Google Scholar]

- Jemal, Alexis, L. Scott Urmey, and Sherika Caliste. 2020b. From sculpting an intervention to healing in action. Social Work with Groups 43: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kant, Jared D. 2015. Towards a socially just social work practice: The liberation health model. Critical and Radical Social Work 3: 309–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, Martin Luther, Jr. 1958. Stride Toward Freedom. New York: Harper and Row. [Google Scholar]

- McGirr, Sara A., and Chris M. Sullivan. 2017. Critical consciousness raising as an element of empowering practice with survivors of domestic violence. Journal of Social Service Research 43: 156–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, Jacob. 1953. Who Shall Survive? Foundations of Sociometry, Group Psychotherapy and Sociodrama, rev. ed. Beacon: Beacon House. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-Williams, Anna, Laura J. Wernick, Jenny DeBower, and Brittany Brathwaite. 2018. Finding relief in action: The intersection of youth-led community organizing and mental health in Brooklyn, NYC. Journal of Youth and Society, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, Kathy A., and Judith L. Stephens, eds. 1998. Strange Fruit: Plays on Lynching by American Women. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, N. Anderson. 2014. Empowerment theory: Clarifying the nature of higher order multidimensional constructs. American Journal of Community Psychology 53: 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seider, Scott, Jalene Tamerat, Shelby Clark, and Madora Soutter. 2017. Investigating adolescents’ critical consciousness development through a character framework. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 46: 1162–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakur, Tupac A., Roger Troutman, Stan Vincent, and Daryl L. Anderson. 1993. Keep Ya Head up [Song]. Available online: https://www.azlyrics.com/lyrics/2pac/keepyaheadup.html (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Sólorzano, Daniel G., and Tara J. Yosso. 2002. Critical race methodology: Counter-Storytelling as an analytical framework for education research. Qualitative Inquiry 8: 23–44. [Google Scholar]

- Speri, Alice. 2017. “I Don’t Think We’re Free in America”: An Interview with Bryan Stevenson. Available online: https://theintercept.com/2017/01/02/i-dont-think-were-free-in-america-an-interview-with-bryan-stevenson/ (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Stoudt, Brett. G., Madeline Fox, and Michelle Fine. 2012. Contesting privilege with critical participatory action research. Journal of Social Issues 68: 178–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Café Community Foundation Creative Commons Attribution. 2015. A Quick Reference Guide for Hosting World Café. Available online: http://www.theworldcafe.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Cafe-To-Go-Revised.pdf (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Thomas, Anita, Rabiatu Barrie, John Brunner, Angela Clawson, Amber Hewitt, Gihane Jeremie-Brink, and Meghan Rowe-Johnson. 2014. Assessing critical consciousness in youth and young adults. Journal of Research on Adolescence 24: 485–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Violence Policy Center. 2020. Annual VPC Study Released for Domestic Violence Awareness Month in October. Available online: https://vpc.org/press/study-finds-black-women-murdered-by-men-are-nearly-always-killed-by-someone-they-know-most-commonly-with-a-gun-6/ (accessed on 31 December 2020).

- Watt, Sherry K. 2007. Difficult dialogues, privilege and social justice: Uses of the Privileged Identity Exploration (PIE) Model in student affairs practice. The College Student Affairs Journal 26: 114–26. [Google Scholar]

- Watts, Roderick J., Matthew A. Diemer, and Adam M. Voight. 2011. Critical consciousness: Current status and future directions. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development 134: 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegman, Robyn. 1993. The anatomy of lynching. Journal of the History of Sexuality 3: 445–67. [Google Scholar]

- Windsor, Liliane, Alexis Jemal, and Ellen Benoit. 2014a. Community Wise: Paving the way for empowerment in community reentry. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 37: 501–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Windsor, Liliane, Pinto, Ellen Benoit, Lauren Jessell, and Alexis Jemal. 2014b. Community Wise: Development of a model to address oppression in order to promote individual and community health. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions 14: 402–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Windsor, Liliane, Alexis Jemal, and Edward Alessi. 2016. Cognitive behavioral therapy and substance using minorities: A meta-analysis. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 21: 300–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Women of Color Network. 2006. Facts and Stats: Domestic Violence in Communities of Color. Available online: http://www.doj.state.or.us/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/women_of_color_network_facts_domestic_violence_2006.pdf (accessed on 28 December 2020).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).