Abstract

Genealogical research is full of opportunities for connecting generations. Millions of people pursue that purpose as they put together family trees that span hundreds of years. These data are valuable in linking people to the people of their past and in developing personal identities, and they can also be used in other ways. The purposes of this paper are to first give a short history of the development and practice of family history and genealogical research in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, which has developed the FamilySearch website, and second, to show how genealogical data can illustrate forward generation migration flows across the United States by analyzing resulting patterns and statistics. For example, descendants of people born in several large cities exhibited distinct geographies of migration away from the cities of their forebears.

1. Introduction

Throughout the world, there is a growing fascination among people of diasporic backgrounds, who have been transplanted in new lands far from the homelands of their biological forebears, to understand their genetic and historical roots. As other articles on this issue indicate, this increasing awareness in people typically involves a strong desire to carry out genealogical research as a way of understanding where they ‘are from’. Among the millions of people undertaking family history research, many may be classified as either serious or amateur genealogists, with the majority probably falling somewhere in between, with genealogy and family history being carried out as one of several part-time hobbies.

Anyone with a newfound desire to seek their roots soon discovers that the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (in this article both the full name of the church and “Church” are used interchangeably, and members of the Church are written as “Latter-day Saints”) is a serious advocate for genealogy, and its members have a deep interest in family history, perhaps more than any other group in the world, with many falling into the category of ‘serious genealogists’.

This article has two purposes. First, it gives a short explanation for this peculiar religious emphasis and underscores the part the Church has played in the growth of genealogical research as a religious imperative for its members. In the process of encouraging genealogy for doctrinal reasons, the Church has developed a resource for the millions of people outside of its faith who enjoy genealogy as a hobby or serious work-related endeavor.1 Second, it gives an example of how the great amount of genealogical data amassed by the Church can be used for more general studies of past populations. Specifically, multiple generations of migration measured by parent to child birthplaces are shown to illustrate cross-country migration from cities across the country. Before explaining the history and background of the Church’s interest in genealogy and family history, we will place the religious practices in context within two cultural constructs. These are, first, activities performed to fulfill religious or cultural obligations and, second, the emergence of personal heritage and identity seeking in connection with genealogical practices. We argue that the Latter-day Saint faith’s emphasis on genealogy and temple work translates into a peculiar type of heritage seeking developed through a sense of religious obligation, which often begets a distinct pattern of personal heritage behaviors, including travel that focuses on places and people of the past.

2. Religious Obligation and the Personal Heritage Quest2

Religions of the world each have their own sets of requirements of action and belief that adherents are expected to follow. For example, in many Christian sects baptism and partaking of the sacrament of communion are required. In Islamic traditions, five key pillars of belief, including the frequency and manner of prayer, almsgiving, and pilgrimage to Mecca, form the foundations of Muslim religious doctrines. In traditions that have come to be called Hinduism, a proscribed way of life is to be followed within the constructs of society to assure a progressive position in the afterlife. In the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, members are required not only to participate in certain religious ordinances such as baptism for themselves, but they are also asked to share their beliefs with non-Latter-day Saints and research their genealogical roots to identify ancestors who were not Church members. The call to share their beliefs has translated into the Church’s large proselyting program that includes thousands of missionaries around the world. The second admonition for Latter-day Saints, to seek out their blood ancestry, has been intimately tied to both the growth of the Church’s genealogical program and to the multiplication of the religion’s most revered houses of worship: its temples (Otterstrom 2008).

One comparison that can be made to the religious emphasis that the Latter-day Saints place on identifying their ancestors is the practice of filial piety among some Asian cultures (such as those in China, Korea, and Japan), which sometimes extends to ancestor worship. Filial piety consists of the concept of the elderly being cared for and respected by the young. The support of the old that is expected of the young often continues after the death of the parent or grandparent. Indeed, in places such as China, elaborate funerary practices that extend long past the funeral itself are tied to the degree to which the living are seen to be respectful to the dead (Ikels 2004). Often, shrines are built to commemorate connections to ancestors and wherein the dead may be adulated and consulted about difficult matters in everyday life. The cultural practices related to filial piety have thus developed their own distinct theological structure replete with ritual, requirement, and spiritual repercussions (Ikels 2004; Chi-Ping 1989; Li 2000). Furthermore, the practices associated with filial piety and ancestor worship have been shown to be instrumental in the development of personal identity within the broader society (Clarke 2000; Hwang 1999).

The Latter-day Saint practice of genealogical research differs from the ancestor veneration of these Asian cultures. The purposes behind the two practices are quite different, as will be seen. However, just as filial piety can lead to a distinct relationship between the young and the old, or the living and the deceased, so does knowing the identity of one’s ancestors extend the concept of personal heritage and invokes a connection between the living and the dead. Catherine Nash (2002) linked genealogical research to the development of an expanded concept of personal identity. Her research into the cultural practices of those involved in Irish genealogy pursuits, for instance, reveals the connection that is evident between the simple practice of learning the identity of one’s ancestors and the multiplication of questions that can arise concerning the evolving national composition or cultural status of that personal identity.

Personal identity is shaped and influenced as a person discovers his/her ancestral roots, and consequently a related desire or urge often emerges. The urging is a quest for understanding, which focuses on the concept of heritage, re-creating, preserving, and identifying with past environments. David Lowenthal’s (1975, 1985, 1996) extensive work on developing the theoretical construct of heritage underscores the underpinning of how modern society values such attention to places that can exist only as attempted re-creations of past places or memories of what once was. In terms of genealogical practices, the efforts that individuals make to connect with the people and places of their ancestral pasts can be classified as personal heritage activities (Timothy 1997). Family historians searching for their ancestors participate in personal heritage tourism, both as a means of obtaining primary data on the life and background of relatives in certain locales and to experience the environments most closely associated with these relations (Meethan 2004; Timothy 1997).

Although many are aware of the emphasis that the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints places on genealogical research, far fewer understand why the Latter-day Saints are so involved in this activity. The academic literature has only scattered references to the importance of genealogical research within the theology of the Church. Some mention the concept of religious obligation in their explanation of Latter-day Saint practices, but often it is discussed in passing while other subjects are emphasized, such as genealogy’s use in teaching history (Johnston 1978), the potential of the Church’s genealogy library as a historical research resource (Gerlach and Nicholls 1975), or the structure and distinctive qualities of Latter-day Saint families (Anderson 1937). Some scholars, such as Douglas Davies (2000), do relate some of the peculiar Latter-day Saint religious practices to their theological roots in more detail.3 Thus, outside of writings published by the Church or its members, there is much room for a greater explanation of the religious reasons behind Latter-day Saint genealogical pursuits in a manner that is more accessible to non-Latter-day Saint readers.

2.1. Church Temples and Genealogy

Visitors to the headquarters of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Salt Lake City, Utah, will find an interesting array of office and religious buildings. We mention a few, but the genealogist would certainly be interested in certain particular places. There is the 28-story Church Office Building, where the day-to-day operations of the Church are coordinated. The Tabernacle (home of the Tabernacle Choir at Temple Square) with its distinctive architecture, the historic Assembly Hall, and the expansive Conference Center, where 21,000 people can meet in one hall (Dietsch 2002), all serve as Church meeting and cultural event venues. Nearby is the Joseph Smith Memorial Building, which was named after the Church’s first prophet.4 It was transformed from its former use as a hotel to its current multiple function capacity, having restaurants, reception areas, Church office and meeting spaces, a movie theater used to present church-produced films to visiting audiences, and areas where visitors can search for their ancestors on computers as they are assisted by Church missionaries.5 That is a good place for budding genealogists to start, but eventually most family researchers find their way to a building a little to the west of the Joseph Smith Building: the Family History Library.

However, the key to understanding why members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints do family history research is not in the library itself, but in the historic temple to the east of the library. More specifically, comprehension of Latter-day Saint genealogical interest comes by discovering the background and purposes of temple worship among the Latter-day Saints. Indeed, after Latter-day Saints go the Family History Library for research purposes, their ultimate destination is one of the Church’s temples. The Salt Lake Temple is the focus point of the whole Church Headquarters complex and is probably one of the best-known icons of the Church. Notwithstanding its fame, this temple is just one of some 160 such edifices that are being operated by the Church around the world. These buildings are different from Latter-day Saint chapels, where regular Sunday services are held. Indeed, temples are reserved for worship services on other days of the week beside Sunday. Additionally, only members of the Church who hold a “temple recommend” that signifies their observance of the Church’s standards of belief and practice can enter the temple (Packer 1999, p. 21).

But what does the temple have to do with the interest of many Latter-day Saints in family history? The Latter-day Saint genealogist goes to the temple to perform certain Church ordinances, such as baptisms for the deceased, for family members and ancestors who have passed away. Once Latter-day Saints have been baptized themselves, they are ready to be baptized as proxy for the dead. Whereas baptisms of the living can be performed by authorized Latter-day Saints in Church meetinghouse baptismal fonts and other bodies of water, baptisms for the dead are only carried out in a temple.6

2.2. Development of the Genealogical Libraries and Resources

The Genealogical Society of Utah was organized in the fall of 1894 to help Latter-day Saints in Utah seek out their own genealogies (Allen et al. 1995). The first president of the society was Franklin D. Richards, one of the apostles of the Church, which shows the Church’s interest in the small association. The society library grew slowly until, in 1911, it had some 2000 volumes of genealogies. At first, the library was only open to paying members but, after many years, the Church incorporated it into its administrative structure in 1944, and the library’s holdings became available to the public (Ludlow 1992, p. 494; Allen et al. 1995). Church members were encouraged to submit their family group sheets (standard format pages listing single nuclear families, with their vital information). In subsequent years, further growth at the library resulted in holdings of some 61,754 volumes and 2050 manuscripts by 1960 (Bennett 1960).

Only two other American genealogical societies predated the Genealogical Society of Utah. They were the New England Historic and Genealogical Society (established in 1844) and the New York Genealogical and Biographical Society (1869). Additionally, a year after the Genealogical Society of Utah began functioning, the Genealogical Society of Pennsylvania was organized in 1895. In the twentieth century, numerous other societies were started in the United States to promote genealogical research. Not only was it inaugurated early in the evolution of genealogical societies, but the Utah society, because of its religious orientation, has also sought to collect records from all over the United States and world, in contrast to many other genealogical societies that are more localized in their focus (Scott 1969).

Since 1960, the growth of the Church’s genealogical library has been significant. It is now known as the Family History Library and has a substantial collection of microfiche, books, microfilm, electronic resources, and periodicals, making its genealogy collection the largest in the world (Familysearch.org 2021a; Warren and Warren 2001).

In Salt Lake City, the Family and Church History Department located at Church headquarters has been charged to administer the effort to help people around the world learn more about their ancestors. Their work has extended to many nations of the earth as they work to gather the names of the world’s deceased. With the rapid development of the Internet, the Church has developed a website that gives the public database access to hundreds of millions of names of people who have died. FamilySearch.org was launched on 24 May 1999 and has grown rapidly since that time (Rasmussen 2000). In 2010, there were 750 million indexed names on FamilySearch.org, and by 2020, that number had grown to 8 billion names (Familysearch.org 2021b and Toone 2020). A related part of FamilySearch is its generationally linked database called FamilySearch Tree or Family Tree. This database is where Church members and others add family names in pedigree and family group fashion, often using the indexed records of the other part of FamilySearch.org. The Family Tree database has grown significantly since 2010, when it contained 300 million names, up until 2015, when it had some 1.1 billion names (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/FamilySearch).

In sum, the collecting, preserving, and disseminating of this vast amount of genealogical records has been made possible through the direct administrative influence and financial support of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints for the clear purpose of enabling Latter-day Saints and others to pursue their personal genealogical research. The religious aims of the Church in connection with temple ordinances must also, of necessity, be remembered in explaining this tremendous emphasis on family history research.

3. American Multiple Generation Migration

In this second part of the paper, we use data obtained from the Church’s Family Tree to analyze migration patterns to and from selected U.S. cities to show the general geographic size and distance of multi-generational migration.

John Hudson (1988) studied the migration of people across the continent using the U.S. Census as his primary data source. Beginning in 1850, the census included the birth state or country for each person listed. In 1880, the states of birth of the individual and their parents were added, and those data are also available for 1900, 1910, 1920, and 1930. With one of those records, Hudson could extract up to three generations of birth data (a child, the parent, and the grandparents). Other scholars have used this type of historical census analysis, including in more recent studies of the population origins of Phoenix (Arreola and Hartwell 2014) and several counties in Nebraska (Aieta 2007).

However, the census’s limitation of only listing the larger geographic area of state or nation means that there is locational accuracy in the historical migration data. Additionally, even when one uses the linked data sources that are becoming available for portions of the population (see Goeken et al. 2011; Ruggles et al. 2011), a researcher is limited in their generations of migration tracing, especially before 1850 when censuses in the U.S. only included the name of the head of the household. Thus, a genealogically based system potentially allows for a longer temporal study period with more personally linked generations in the analysis.

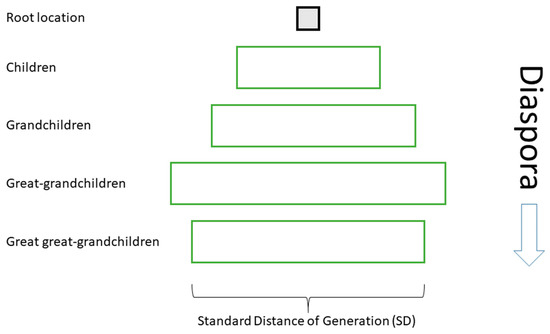

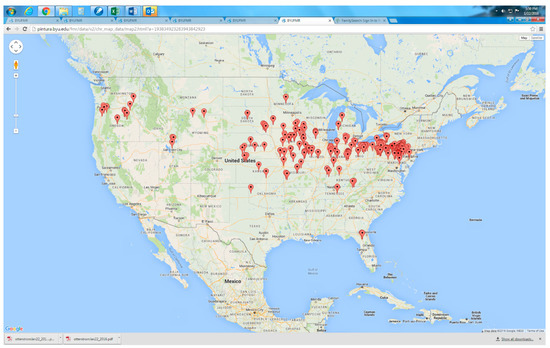

We used the method described and implemented by Otterstrom and Bunker (2013, 2018) to extract data from the Family Tree system for multiple cities across the United States during the 19th century and into the 20th century. We extend the research from Otterstrom and Bunker’s work, which just considered family migration going backward in time (parents, grandparents, great-grandparents, etc.), to retrieving and analyzing forward migration (children, grandchildren, etc.). The searches return the locations of either ancestors or descendants, which are mapped. From those locations, the center point of each generation’s migration can be obtained, as well as the size of the dispersion (or how far away the children were born from the source city). We compute a migration pyramid for each sample city, along with associated maps and statistics, and compare the results to show how each city had its own historical migration trajectory and pattern (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Generational Migration Pyramid (derived from Otterstrom and Bunker 2013, p. 547).

Sample cities are spread north to south across the middle section of the country and include Chicago, Cincinnati, Detroit, Indianapolis, Louisville, Memphis, Milwaukee, Mobile, New Orleans, and St. Louis. A search was performed for each city (known as the “Root” location) for up to 200 people born there in 1850 (size of sample varied by city). Once those people were found, the system searched for the children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren of these “Root” individuals and then computed some of the statistics introduced by Otterstrom and Bunker (2013), which they used in their backward in time searches. It is important to note that the spatial distribution of children and grandchildren are biased by the number of children born to a couple, so the most reliable results are those that have large numbers of individuals in the sample.

Analyzing the geography related to the pyramidal expansion through migration from the root place helps show how persistent the population in one place is across space and the statistics related to this persistence can be used to show the differences among communities in terms of their keeping their resident population close by or stable over time. Several spatial measures can help depict and quantify population migration from the root place. The statistics we use in this study from Otterstrom and Bunker (2013) include:

- Mean Migration Distance (MMD)—Mean distance between the birthplaces of children and their parents who were natives of a single locale at one point of time;

- Standard Distance of Generation (SD)—Shows how relatively dispersed the locations of all birth places are from the weighted mean center of one particular generation;

- Descendant Dispersal Index (DDI)—Average migration distance (for all people in that generation) calculated between two particular generations (e.g., compare parents’ to children’s generation);

- Descendant Concentration Index (DCI)—Uses the standard distance of generation (SD) statistic and compares it between different generations (e.g., compare children’s to grandchildren’s generation).

To illustrate how to interpret these statistics, we used the data from Indianapolis and New Orleans because they both had a large group of individuals retrieved from 1850 and forward generations and they are in different regions of the country. The mean migration distances (MMD—root—1st) were similar between the cities for the first generation (291 to 325 miles) (Table 1). However, the grandchildren (Root to 2nd generation) in the two cities had greatly different mean migration distances from their place of birth to the root city (526 to 310 miles). The same goes for the mean distances from the origin city to the 3rd generation where the grandchildren of people born in Indianapolis in 1850 were born an average of about 250 miles farther away from the root city than the grandchildren of people born in New Orleans in 1850 (591 to 339 miles).

Table 1.

Mean Migration Distance (MMD) by Generation Pair from those born in these Cities in 1850 (in miles).

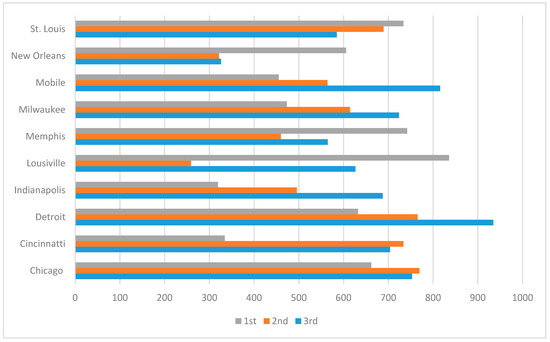

Standard distance is a standard spatial statistic of “the square root of the averaged squared distance” of a number of locations to a central point, and is not the same thing as the aspatial standard deviation statistic because all standard distance values are positive (Rogerson 2015, p. 43). Thus, standard distance of generation (SD) is a useful way to quantify, in one number, the relative birth locations of one generation compared with the next. Bigger SD values mean that birthplaces in two generations were relatively more dispersed, indicating a larger generational migration source area, while lower SD values might point to chain migration caused by descendants from generation to generation migrating together, resulting in more concentrated birth locations. Figure 2 illustrates the pyramidal generational migration for descendants for the ten sample cities. Some cities showed increasing standard distance in each successive generation, while others did not. This points to distinct local settlement factors around each of the study cities that led to their differences (e.g., greater job opportunities in the areas where people stayed closer in the next generation). This, or cultural factors, could have been the case with New Orleans, while cities like Detroit had greater dispersion of their 1850 individuals over the years.

Figure 2.

Standard Distance by City of Succeeding Generations from Individuals Born in 1850 (distance in miles).

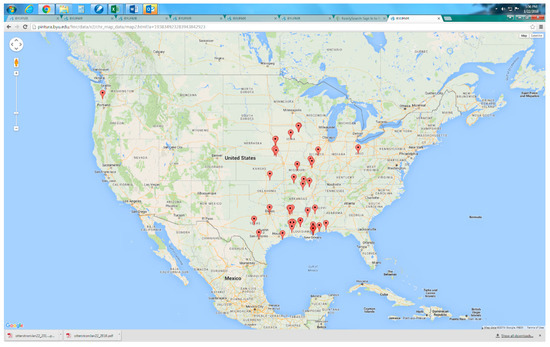

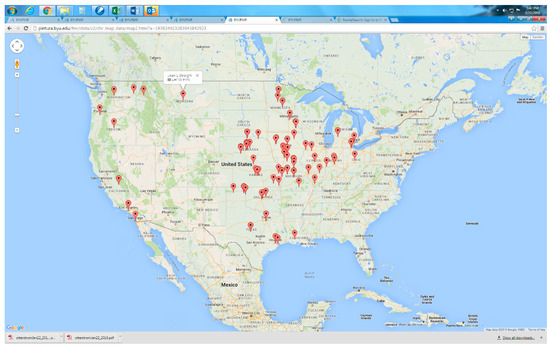

To clarify: the MMD is the mean migration distance between generations of all children to their parents between generations or from the second or third generation to the first generation, while the SD measures the spatial distances of all individuals within a single generation. Thus, Indianapolis’s first generation standard distance was 319 miles compared with New Orleans at 606 miles, while these values were inverted for the second generation with New Orleans’s at just 321 miles and Indianapolis at 496 miles, meaning much more spatial dispersion for Indianapolis descendants (born in the late 1890s). The reasons for these differences appears to be related to the fact that the children of New Orleans-born individuals tended to be born up the reaches of the Mississippi River system, which spread them out initially, but the next generation did not spread much from those areas (Figure 3). On the other hand, the Indianapolis descendants dispersed to the west in the first generation, and they dispersed outward and westward even more in the second generation (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Birth locations of grandchildren of individuals born in New Orleans in 1850.

Figure 4.

Birth locations of grandchildren of individuals born in Indianapolis in 1850.

The varying MMDs by generation pair and among the ten sample cities show that time and place affected the movement of families (Table 1). For example, the MMDs from the second to third generations were small in Chicago, but quite large in Indianapolis. This makes one wonder what made the cities descendants move so differently across time and space.

Dividing the generations into female and male subgroups shows another level of spatial differentiation (Table 2 and Table 3). These widely varying numbers indicate that birth locations of male children and grandchildren of men and female children and grandchildren of women were affected by both geography and gender issues.

Table 2.

Mean Migration Distance (MMD) by Generation Pair from those born in these Cities in 1850—Males Only (in miles).

Table 3.

Mean Migration Distance (MMD) by Generation Pair from those born in these Cities in 1850—Females Only (in miles).

Diaspora

The geographical diaspora of the descendants migration pyramid (Figure 1) can be described by two related indices: dispersal and concentration. The descendant dispersal index (DDI) compares MMD values between different generations of descendants. The denominator MMD in the index is the one from the generation more proximate in time to the root location (usually the generation of the root parents’ location to their children’s locations). The DDI indicates how much the descendants of parents in one generation spread compared with the movements in another generation, showing the relative dispersal of these descendants.

DDI values that are smaller than 1.0 point to decreasing MMD, or less distant migration over time, while values over 1 show that migrations over succeeding generations were more mobile and dispersed. For example, the DDI for 1850 Indianapolis (Table 1) comparing the first two generational migrations is 1.2, pointing to greater migration dispersion for children to grandchildren (1st to 2nd generations) compared with the root to their children’s generation (root to 1st generations). In New Orleans, the same value was 0.54, meaning that the relative migration distances were inverted. This helps quantify, in relative terms, the inverting MMD values discussed above. These statistics therefore illustrate the concept of diaspora over successive generations, with Indianapolis descendants spreading out more over time.

The related descendant concentration index (DCI) measures how localized or concentrated in space descendants were, according to their birthplaces. In effect, it indicates how much descendants tended to cluster through succeeding generations. This index takes the standard distance of birth locations in one generation (numerator) and divides that by the standard distance of another generation that is closer in generational time to the original root location. An index value greater than 1.0 translates to that relevant generation (e.g., grandchildren) being more dispersed in their birth locations than the generation of comparison (e.g., the children). The forward-looking DCI shows the relative size and locality of the descendants of those originating (born), with at least one ancestor, in one locality and depicts the destinations to which the people coming from one destination were dispersed. The comparative differences in this index between different sets of generations can be instructive in showing how descendants’ migration varied in a number of communities over time.

Initially, one might hypothesize that the values of DCI’s would always be greater than 1.0 because generational starting points would likely be more dispersed in succeeding generations than in the first generation. That was only the case sometimes. For example, the standard distance for children of parents born in Cincinnati in 1850 was 335 miles and for the grandchildren it was 734 miles. Thus, the DCI between those two generations was 2.2, which indicates a noteworthy dispersion over the course of two generations. In contrast, St. Louis’s DCI for the same two generations was 0.94, meaning that the second generation (grandchildren) was relatively less spread out than the first (children).7

4. Summary

This paper has explained how and why the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has developed such extensive genealogical resources, and it has also illustrated how the Church’s genealogical database can be queried for interesting data concerning the settling and movement of people across the United States. The religious purposes for family history research are what drive the incredible growth of the FamilySearch Family Tree, yet the opportunities for using the millions of multi-generationally linked records to research important trends in the settlement and movement of people across the U.S. and other parts of the world only add to the value of the system.

With some 837 grandchildren located from a sample of 300 people born in 1820 in Pennsylvania, a fascinating picture of both the “stickiness” of Pennsylvania and the forward pull of the west along a nearly latitudinally focused line. This migration picture raises many questions, but it also has the visual pointers to help one begin to find the explanations (Figure 5). As the Church’s database continues to expand, many more potential avenues of research will be become apparent to those wishing to understand the great process of peopling our planet with families that span the generations and who have been tied together across time and place.

Figure 5.

Birth locations of grandchildren of individuals born in Pennsylvania in 1820.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M.O.; methodology, S.M.O., B.E.B. and M.A.F.; software, B.E.B. and M.A.F.; validation, S.M.O. and M.A.F.; formal analysis, S.M.O.; investigation, S.M.O.; resources, S.M.O.; data curation, S.M.O. and M.A.F.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M.O.; writing—review and editing, S.M.O.; visualization, S.M.O., Bunker, and M.A.F.; supervision, S.M.O.; project administration, S.M.O.; funding acquisition, S.M.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received funding from Brigham Young University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aieta, Nicholas Joseph. 2007. Frontier Settlement and Community Development in Richardson, Burt, and Platte Counties, Nebraska, 1854–1870. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Department of History, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, NE, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, James B., Jessie L. Embry, and Kahlile B. Mehr. 1995. Hearts Turned to the Fathers: A History of the Genealogical Society of Utah, 1894–1994. Provo: BYU Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Nels. 1937. The Mormon Family. American Sociological Review 2: 601–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arreola, Daniel D., and Rio Hartwell. 2014. Phoenix Population Origins, 1870–1900. Geographical Review 104: 439–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, Archibald F. 1960. Saviors on Mount Zion. Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chi-Ping, Yu. 1989. Theology of Filial Piety: An Initial Formulation. Asian Journal of Theology 3: 496–508. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, Ian. 2000. Ancestor Worship and Identity: Ritual, Interpretation, and Social Normalization in the Malaysian Chinese Community. Sojourn 15: 273–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, Douglas J. 2000. The Mormon Culture of Salvation. Aldershot and Burlington: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Dietsch, Deborah. 2002. Building The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints Conference Center. New York: Edizioni Press. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: http://www.familysearch.org/wiki/en/Family_History_Library (accessed on 10 February 2021).

- Available online: http://www.familysearch.org/about (accessed on 10 February 2021).

- Gerlach, Larry R., and Michael L. Nicholls. 1975. The Mormon Genealogical Society and Research Opportunities in American History. The William and Mary Quarterly 32: 625–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goeken, Ron, Lap Huynh, T. A. Lynch, and Rebecca Vick. 2011. New methods of census record linking. Historical Methods 44: 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudson, John C. 1988. North American origins of middlewestern frontier populations. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 78: 395–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Kwang-Kuo. 1999. Filial Piety and Loyalty: Two Types of Social Identification in Confucianism. Asian Journal of Social Psychology 2: 163–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikels, Charlotte, ed. 2004. Filial Piety: Practice and Discourse in Contemporary East Asia. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, A. Montgomery. 1978. Genealogy: An Approach to History. The History Teacher 11: 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Liu. 2000. Ancestor Worship: An Archaeological Investigation of Ritual Activities in Neolithic North China. Journal of East Asian Archaeology 2: 129–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowenthal, David. 1975. Past Time, Present Place: Landscape and Memory. Geographical Review 65: 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowenthal, David. 1985. The Past is a Foreign Country. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lowenthal, David. 1996. Possessed by the Past: The Heritage Crusade and the Spoils of History. New York: The Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ludlow, Daniel H., ed. 1992. Encyclopedia of Mormonism. New York: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- McConkie, Bruce R. 1966. Mormon Doctrine, 2nd ed. Salt Lake City: Bookcraft. [Google Scholar]

- Meethan, Kevin. 2004. To Stand in the Shoes of My Ancestors: Tourism and Genealogy. In Tourism, Diasporas and Space. Edited by Tim Coles and Dallen J. Timothy. London: Routledge, pp. 153–64. [Google Scholar]

- Nash, Catherine. 2002. Genealogical Identities. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 20: 27–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otterstrom, Samuel M. 2008. Genealogy as Religious Ritual: The Doctrine and Practice of Family History in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. In Geography and Genealogy: Locating Personal Pasts. Edited by Dallen J. Timothy and Jeanne Kay Guelke. Aldershot: Ashgate, pp. 137–51. [Google Scholar]

- Otterstrom, Samuel M., and Brian E. Bunke. 2013. Genealogy, migration, and the intertwined geographies of personal pasts. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 103: 544–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otterstrom, Samuel M., and Brian E. Bunke. 2018. Genealogical Genealogy and the Generational Migration of Europeans to America. In The Routledge Companion to Spatial History. Edited by Ian Gregory, Don DeBats and Don Lafreniere. London: Routledge, pp. 35–53. [Google Scholar]

- Packer, Boyd K. 1999. The Holy Temple. In Temples of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Salt Lake City: Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, pp. 20–7. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen, Russell C. 2000. Computers and the Internet in the Church. In Out of Obscurity: The LDS Church in the Twentieth Century. Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, pp. 274–85. [Google Scholar]

- Rogerson, Peter A. 2015. Statistical Methods for Geography: A Student’s Guide, 4th ed. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Ruggles, Steven, Evan Roberts, Sula Sarkar, and Matthew Sobek. 2011. The North Atlantic population project: Progress and prospects. Historical Methods 44: 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Ruthven, Malise. 2001. Review of The Mormon Culture of Salvation. Journal of Contemporary Religion 16: 239–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, Kenneth. 1969. Genealogical Societies: Introduction, General Description and Brief History, in World Conference on Records and Genealogical Seminar: Papers. [Area K: Genealogical Societies: Hereditary and Lineage Societies]. Salt Lake City: Genealogical Society of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. [Google Scholar]

- Timothy, Dallen J. 1997. Tourism and the Personal Heritage Experience. Annals of Tourism Research 34: 751–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toone, Trent. 2020. ‘Tip of the Iceberg’: How It’s Now Possible to Search 8 Billion Names on FamilySearch.org. Deseret News. Available online: https://www.deseret.com/faith/2020/9/25/21455940/familysearch-records-family-names-lds-mormon-genealogy-history-ancestors-relatives-rootstech (accessed on 25 September 2020).

- Warren, Paula S., and James W. Warren. 2001. Your Guide to the Family History Library. Cincinnati: Betterway Books. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | While there are subtle differences, genealogy and family history are both used here to signify the practice of researching genetic lineage and historical backgrounds of families and individuals. |

| 2 | |

| 3 | See also Ruthven (2001) for a detailed review of Davies’ book and other related publications. |

| 4 | Joseph Smith lived from 1805–1844. |

| 5 | These missionaries are assigned to help the public search for their ancestors on the Church’s computer system and they are also available to answer questions concerning the beliefs of the Church and to refer visitors to proselyting Church missionaries in the tourists’ home cities. |

| 6 | Latter-day Saints practice baptism by complete immersion in water by a priest or a Melchizedek priesthood holder (McConkie 1966, pp. 69–72). Performing baptisms for those who have died can be controversial as it relates to other religious traditions. For example, for a time, the Church allowed proxy ordinances for Jewish Holocaust victims, which, when discovered, was formally opposed by the Jewish community. The Church agreed not to allow the practice, although the implementation of the policy since that time has not always been perfect. |

| 7 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).