Decolonizing Ways of Knowing: Heritage, Living Communities, and Indigenous Understandings of Place

Abstract

Tell me the truth. Didn’t you come from the other side?Yes. I was on the other side.You came back because of me?Yes.You rememory me?Yes, I remember you.You never forgot me?Your face is mine.—Toni Morrison, Beloved (Morrison 1987)

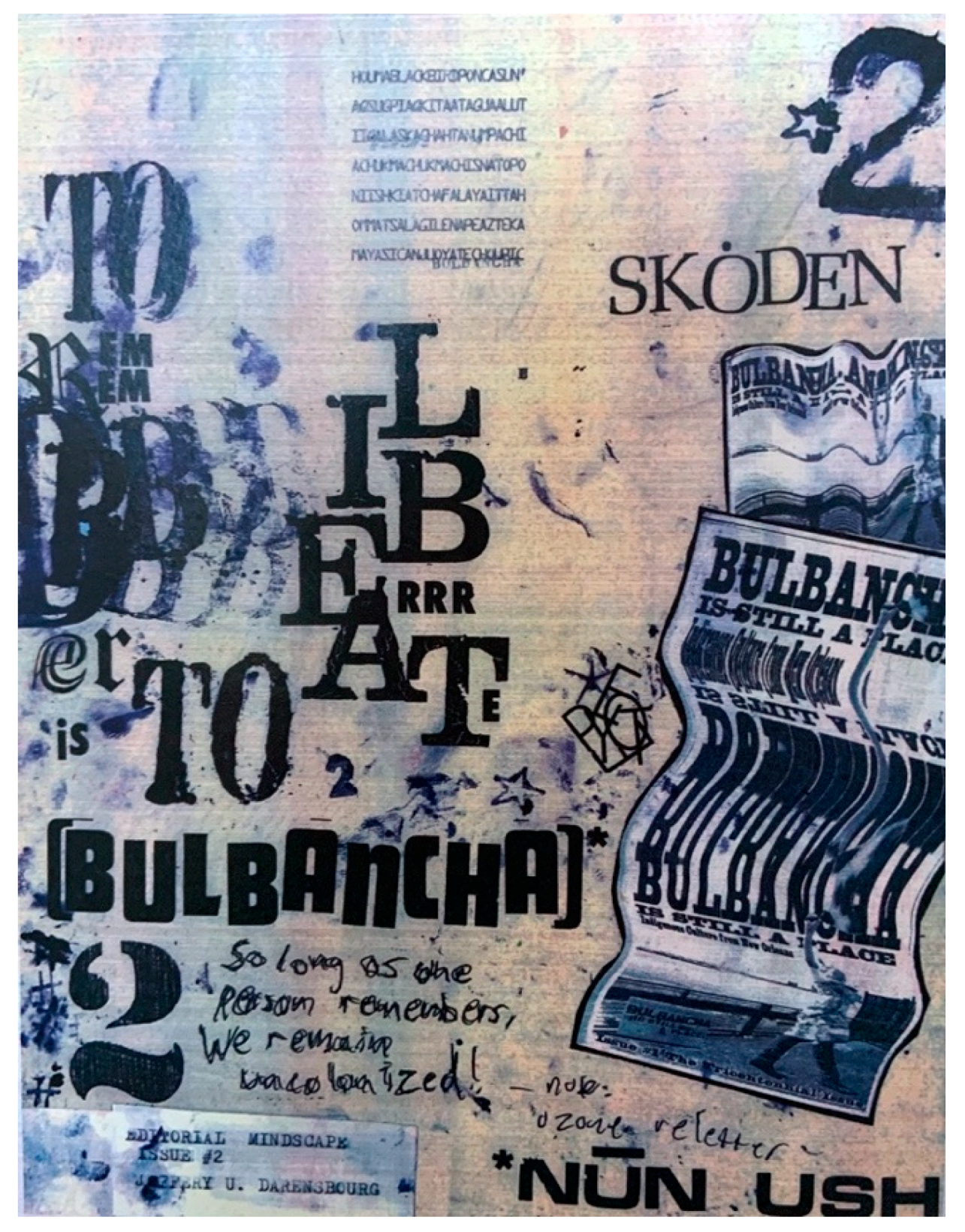

I brought them cigarettesdrew in a first coarse breathblinked briefly and saw themflash of blood memorythey saw what was still themflash of the eye at duskwhen I doubt I’m the oneto tell this tale I hear themfrom that Atchafalaya earthworkte nakoy get up and tell it—Jeffery Darensbourg, “Impostoral”

1. Memory Work: The Use of Multi-Media in Critical Genealogies

The origins of “Decolonizing Ways of Knowing” began in conversations Antoinette and I had about the importance of public scholarship in helping families and communities confront oppressive histories in their lineages. In her first book, Speaking for the Enslaved, Antoinette writes:If the purpose of violence is to extinguish certain people, knowledges and perspectives, then memory continues to resist that violence. Thus the moral burden of the past in the present includes the refusal to succumb to the world of violence and amnesia…and [works] against the comfort of monologue.

Many people have posed the question: Why go back to the plantation? Why bother reconstructing a negative time in American history? I understand their sentiment and skepticism… In school I remember stifling feelings of embarrassment behind a mask of indifference when slavery was discussed. I saw no use in looking back at that period in history.

The dolls are mostly gone now, but Ronald refused to forget them. In his interpretation of the exhibit, he explains:rainrain drenches the cityas we move paststuffed black mammieschained to Royal St. praline shops.check it out

I decided to use boats and masks and figurines to show connections across places. The masks represent West African culture and the boats represent those slave ships… And in the middle, I put an Aunt Jemima doll with its image of racism.

Ronald continued to exhibit one to reconcile two images in his mind—the woman who raised him, and a racist caricature of Black women. Calling forth W.E.B. Dubois’s double consciousness (DuBois 2014), he created what anthropologist Gina Athena Ulysses calls rasanblaj—a Haitian Kreyòl word that means “an assembly, compilation, enlisting, regrouping (of ideas, things, people, spirits)” to challenge his audiences towards more honest discourse of our sense of the past (Ulysses 2015).It’s easy to just push history to the side, but I don’t want to do that because it’s there. To be fair, I want to identify with it all. When I talk about my mama coming off that sugarcane plantation, I’m not ashamed of that because that’s where my roots are. As I was growing up, my mama always had her hair tied up in a scarf. When I see this doll, I remember that, too, and think about how my family survived those cane fields.

In the years since these violent acts against freedom, stories of San Malo, the participants of the slave revolt, and the legacy of Bras Coupé have been part of counter-memories that focus on the lives, rather than deaths, of the early revolutionaries (Barnes and Breunlin 2019; Wagner 2019). In protest, art, film, songs, and altars, the dead are still with us. See Figure 3 and Figure 4.No Mardi Gras procession, no special pageant that I know… ever attracted such surging crowds as were witnessed under that broiling, solstitial sun. Men, women, and children; whites and blacks, freedmen and slaves; professional men and laborers in their working blouses all seemed to have gathered there to satisfy their curiosity.(Castellanos quoted in Wagner 2019, p. 11)

After years of critiquing the way racial categories have been used to divide and conquer, anthropologists have also become mindful of other traps of language, including “the most problematic connotations of ‘culture’: homogeneity, coherence, and timelessness” (Abu Lughod 1993, p. 14). In this special issue, we recognize that the word “Indigenous” has been reclaimed by many First Nations, while also acknowledging that the term developed out of early anthropological thought in the early 20th century when the discipline assumed, “cultures were bounded and isolated from each other and that they have a purity and authenticity that can be identified and catalogued” (Regis 2019, p. 152). Memory work breaks these assumptions down (Harrison 1991; Davis and Craven 2016).Definition is itself at the roots of racism: the way we reduce the world to a word, and gag the mouths of others with our labels. One man put it very succinctly: “Amongst ourselves we are people, whites turn us into Aborigines.”

Inspired by the cosmopolitan ethic of Bulbancha, we have invited scholars and artists from Africa, the South Pacific, and the United States to develop a cross-cultural dialogue about decolonizing genealogy. Following Saidiya Hartman’s “history of the present,” this project works:Bulbancha, “the place of many languages,” or “the place of many tongues,” is the original name for this area… Bulbancha is much older than New Orleans. It is also closer to the heart of the matter. Before the first Europeans came here, it was a place where people from around 40 distinct Native groups crisscrossed, traded, followed game and fish, moved to rising and falling waters and interacted with one another. It was a place of diversity, and changes, where people came and went in search of what they needed, including the Chitimacha, Houma, Chawasha, Washa, Acolapissa, Tunica-Biloxi, Baogoula, Natchez, Taensa, Atakapa-Ishak, and other groups as well. That was Bulbancha then; this is Bulbancha now: a complex, multi-ethnic, multicultural place.

Here, we want to highlight our contributors who have combined genealogical research with creative nonfiction and autoethnography, as well as artwork, film, and a critical examination of archives, to contribute dynamic experiences with family, ancestors, and land. Through the open-source format of this journal, we hope to redistribute critical genealogies back to the communities represented in the articles in ways that contribute to dialogues already at play, and to provide new opportunities to look at personal and collective lineages.to illuminate the intimacy of our experience with the lives of the dead, to write our now as it is interrupted by this past, and to imagine a free state… as the anticipated future of this writing.

2. Honoring Place Through Home Languages

Similarly, in Kayang and Me, Kim Scott meditates on how learning words in Noongar, an Indigenous language from Western Australia, helps connect to local landscapes. He shares the work of lexical cartographer Jay Arthur, who has asked Anglo-Australians to consider the limitations of English words used to describe Australian ecologies. For instance, “[t]he word ‘drought’ in a country where rainfall is naturally irregular…encourages us to be disappointed, to feel cheated, to see the land as hostile (Scott and Brown 2005, p. 219). Scott provides another example in the word “river,” which:No English words are good enough to give a sense of the links between an Aboriginal group and its homeland. Our word “home,” warm and suggestive though it may be, does not match the Aboriginal word that may mean “camp,” “hearth,” “country,” “everlasting home,” “totem place,” “life source,” “spirit centre,” and much else all in one. Our word “land” is too spare and meagre. We can now scarcely use it except with economic overtones unless we happen to be poets. The Aboriginal would speak of “earth” and use the word in a richly symbolic way to mean his shoulder” or his “side”.

The work of holding onto endangered languages can lead different ways of knowing. Robin Well Kimmerer writes of how she learned a “grammar of animacy” by studying her family’s language. In English, verbs make up 30% of the vocabulary, but in Potawatomi, they account for 70%. She explains what happen when nouns are transformed into action words:only approximates what in Australia is known as a river Along the south coast a “river” is typically a tenuously linked sequence of ponds barred by a sandy beach from reaching the sea… Kayang Hazel tells me the Noongar word for river is bily. It is also the word for navel.

Just as we would recoil in English from someone who refers to a person as “it,” so would a fluent Potawatomi speaker if they heard someone objectifying plants or animals (Kimmerer 2013, p. 56).When bay is a noun, it is defined by humans, trapped between its shores and contained by the word. But the verb wiiwegamaa—to be a bay—releases the water from bondage and lets it live. “To be a bay” holds the wonder that, fro—this moment, the living water has decided to shelter itself between these shores, conversing with cedar roots and flocks of baby mergansers.

The Fitzroy’s wetlands and tributaries stretch to the edge of the Great Sandy Desert, where many Walmjarri, Jaru, and Mangala people lived on their traditional land until the 20th century and are still fluent in their languages.[T]he river was formed in the beginning of time by Nyikina ancestor, Woonyoomboo. Woonyoomboo is the human face of the Mardoowarra and in partnership with Yoongoorrookoo, the sacred ancestral spiritual living being, created the river valley tracks. Woonyoomboo was an explorer, map maker, and scientist who named the places, animals, birds, fish, plants, and living water systems.

Slowing down to discover what these names are referencing, we learn that “Yarday” means “North” in Warrwa, a language similar to Nyikina that is now extinct—one of more than 100 Aboriginal languages which have been lost since British colonization (McGregor 1994; Poelina 2013). Yarday is a “cardinal direction” in Warrwa, one of four quadrants that form a fixed frame of reference for understanding where something or one is located (McGregor 2006, p. 149). In this case, Yarday helps us understand that the town of Derby was founded in the northern territory of Warrwa country in 1883. Named after Edward Henry Stanley, the fifth earl of Derby and the secretary of state for the British colonies, Britain established it to support the growing pastoral industry, which was simultaneously displacing many Aboriginal people from their land throughout the region. Under the arc of this history, the last name Bessie references, “Budalah,” can be seen as an act of reclamation within these colonized boundaries. Overseen by the Winun Ngari Aboriginal Corporation, it is a small community within Derby that was developed to support Aboriginal housing needs.Nykinia and Warrwa people belong to here. This is their country. They used to call it, in the olden days, Yarday. Now they call it Badulah. Them white man named it Derby.

In many ways, Aboriginal English became a trade language—a liminal space between Indigenous communities that were often displaced after British colonization. For instance, Carlene Wise’s mother (Walmajarri) and father (Mangala) came from Desert Country. She explains that, “Whitefella mixed Mangala up with Nyikina and moved them to a big block out from the Fitzroy River called Looma” (Breunlin and Haviland 2008, p. 70). Amongst the other languages, she learned her mother’s tongue from the Great Sandy Desert:I only know talking Bardi… My mum used to talk to us in Nyikina… I understand the old people talking to me, but I answer them in English.

Paul Stoller has written about anthropologists being “sojourners of the ‘the between,’” yet Biddy, Bessie, and Carlene are also sojourners; members of transnational families who have experienced both the insight and disconnections that come from moving between places and languages (Stoller 2009, p. 4). Carlene’s family still returns to the Great Sandy Desert for funerals, but she does not feel as comfortable there as she does by the Fitzroy. “After a few days, we wanted to go back to our river” (Breunlin and Haviland 2008, p. 71). See Figure 8.I grew up speaking Walmajarri. It’s an easy one—Nyikina and Mangala are too hard. When they talk those languages, I tell them to speak English.

3. Embodied Memory: Returning to the Dead

Amongst the òrisa (dieties) that are worshipped is Egúngún-Oya, the mother of the collective spirits of the ancestors. In Yorùbá, the word egúngún:I have never seen anything like it before. I have been to so many Yoruba towns, but there appears to be none that is comparable to Oyo. It is like every household has a babaláwo (Ifa diviner) or two, as well as other traditional religion worshippers such as Sango, Obatala, and Osanyin as members. Even some young boys between the ages of 18 and 20 years, who were my students, were practicing babaláwos or ardent worshippers of one form of Yoruba traditional religion or another.

“O-ya” is also a compound word which translates as “she tore.” Revered by market women, Egúngún-Oya oversees the cemetery, and is called upon for transformation. Òrisa of wind and lightning, she harnesses the destructive power of tornadoes that form along the Guinea Coast when winds from the Atlantic Ocean, the Saharan desert, and eastern dry savannah converge to bring about change—the same winds that build in the ocean to make land fall as hurricanes in the Caribbean and southern United States. For this special issue, Abiodun shares his research on two egúngún from Òyó. See Figure 9.is a compound word formed by the combination of morphemes/e + gún + gún/, literally “that which facilitates or brings about stability, unity, peace, and joy” among others.

In the United States, the descendants of slave owners are often reluctant, or outright hostile, at the suggestion that they should pay debts to those they enslaved. The memories are often preserved outside of dominant narratives, and through family and community practices. See Figure 10.Why should you not pay your debts to the slave spirits the way we Ewe do? You would be better off for it their spirits are powerful; they can help, heal, and protect you when you need them, if you honor them fully.

Once again, emotion is the first sign that a larger story needs to be told. When the feeling runs against dominant discourse, it may take time to begin to incorporate new ways of knowing. Denise reflects:Her question still haunts me to this day. It was as if she had time-travelled and caught the quizzical look on my ten-year old face as I observed how my grandparents ate. They used utensils, but there was also a mixing of various foods and a use of the thumbs with the pointer finger and middle finger to scoop mixed flavors of cornbread with chicken and greens into a delightful bite in a way that may be similar to how West Africans use fufu. I asked my mother why my grandparents did this and was dismissed. It was as if my observation was shameful or not polite enough to prompt further inquiry.

As I have gotten older, I have delighted in picking up pieces of arugula with my fingers at formal or casual dinners in public or in my own home. I frequently mix my foods, putting salad on top of beans and rice and mixing them all together. Doing so honors the cultural memory that I have retained from my grandparents and celebrates the way they enjoyed eating—with utensils, as well as with their hands.

4. Carving out Space: Genealogies of the Land

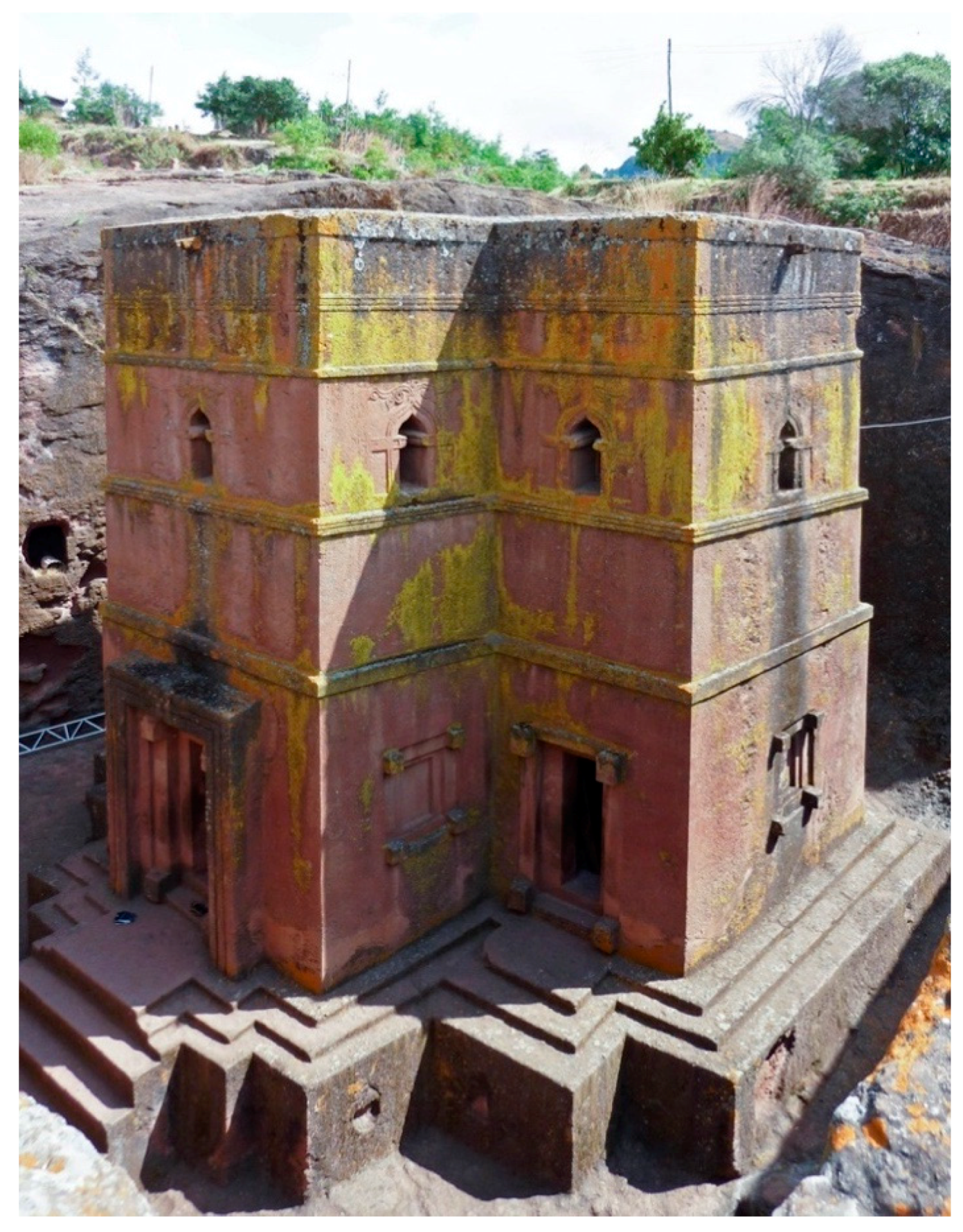

The Tewahido Church traces its roots genealogically back to King Solomon and is considered the indigenous religion of most Ethiopians. See Figure 12.Like other indigenous perspectives, rather than being conceived as a tabula rasa, waiting to be authored or acted upon by human beings, the traditional beliefs of Ethiopians understand place to have agency that can impose demands on human beings… Like other African philosophical traditions…which view life as a sacred connection among the human, the non-human and the spirit world, Lalibela’s churches are places embodied with spiritual meaning and identity.

Amongst Tewahido believers, the important sacred text is ገድለ ላሊበላ, The Acts of Lalibela, which was written in Ge’ez, and recently translated into Amharic. For his article, Yirga translated parts of The Acts into English “as a way to make the primary storylines in the text more accessible” (Woldeyes 2019, p. 9). Spending time in the churches was an important part of Yirga’s education. Even before he was able to read, the artwork that was displayed throughout the churches told stories of connecting the Tewahido Church back to the Middle East. As he grew up, he heard the story of how when King Lalibela was born, he was swarmed by bees, which was seen as an omen for miraculous deeds to come, and watched as people came to Bete Giyorgis (St. George) to receive holy honey that dates back to Lalibela’s time in 900 CE.attending Sunday school and from listening to the stories of the hermits, monks, nuns, priests and spiritual scholars who lived in communion with the church and our community… Other times, my friends and I gathered in the compound of Bete Medhanialem and in the caves of Amanuel and Bete Mariam churches to study scripture with the monk-scholar Aba Zekarias. He was referred to as Arat Ayina, Four Eyed—someone with the ability to see the past as well as the future. Arat Ayina knew infinite stories, verses and fables. He read from the ancient books written in Ge’ez, and used Amharic to educate us in the 81 books of the Ethiopian

The symbolism of bees for King Lalibela, who went on to create some of the most stunning architecture on the planet, may be explored in more depth as the relationship between bees and their environments continues to be studied.The intricacy and complexity of the communication system (and the accuracy and precision incorporated into it) demonstrates a truly amazing capacity for bees to encode and communicate information in the abstract, symbolic way that would shame many a communications or GIS specialist… The entire repertory of bee dances with all of its innumerable parts and variations falls within a mathematical schema unknown to any architect. The only other known physical process to which such mathematics applies concerns quarks in quantum theory… If [bees somehow have this knowledge] then bees “know” (with a tiny brain) a kind of mathematics known to only a handful of people, but they may also be able to do what no human appears ever able to do—operate in quantum fields without disturbing them.

Since UNESCO “inscripted” the churches in Lalibela, many residents of the rock-hewn buildings, as well as the surrounding neighborhood, were forced to relocate. Yirga explains that UNESCO adopted:a wide array of practical skills and acquired intelligence in responding to a constantly changing natural and human environment… The practice and experience reflected in metis is almost always local.

Lalibela is not the only local community that has had a difficult time reconciling with UNESCO. While it may seem as an exceptional honor to be named a treasure of the world, the impacts of conservation and the development of sites for an international tourist market are often managed outside the communities that have historic ties to the sites (Adams 2006; Collins 2008; Davis 2015).new concepts such as “heritage,” “property,” “conservation,” and “authenticity” that do not incorporate the meanings and experiences local people have had with the churches in the region. The World Heritage Committee insisted on the creation of boundaries, buffer zones, and conservation zones around “the property”.

Majestic remnants of tall rainforest growing on sand and half the world’s perched freshwater dune lakes are found inland from the beach. The combination of shifting sand-dunes, tropical rainforests and lakes makes it an exceptional site (UNESCO).

For generations, the Wondunna clan of the Badtjala Nation has countered this argument with their cultural activism, writing, and art. Following in her family’s lineage, artist and scholar Fiona Foley has created a stunning body of work dedicated to K’Gari. See Figure 14. In a review of her artwork in our special issue, “Source to Subject: Fiona Foley’s Evolving Use of Archives,” art historian Marina Tyquiengco explains, “Over the years, her practice of engaging the archive to connect with the genealogy of the Badtjala has expanded to include the artist as a subject, witness, and/or participant” (Tyquiengco 2020). In her own article in this special issue, “The People of K’Gari/Fraser Island: Surviving 250 Years of Racial Double-Coding,” Fiona weaves together her family’s genealogy with the history of the island, including the cultural activism of her mother, Shirley Foley, who was central to the Badtjala’s Native Title Claim (Foley 2020).The High Court held that “when the tide of history has washed away any real acknowledgment of traditional law and any real observance of traditional customs,” the foundation of native title disappeared and native title rights were extinguished. As if merely substituting the notion of culture for an older version of race, the court argued that if Aboriginal culture interbred with another “heritage” to some undefined degree, it forfeited these rights.

Of particular concern for Fiona is the preservation of the Badtjala language. She edited and republished her mother’s book, Badtjala-English, English-Badtjala Word List. In this special issue, we also have the opportunity to watch a short film she directed on K’gari, Out of the Sea like Cloud. With the help of her mother’s dictionary and singer/songwriter Telia Watson, the film repatriates a Badtjala song back into their language. As Fiona writes in her article, “Our language had been sleeping for many years and was awoken. It was the first time the full weight of my mother’s work had been activated in such a space” (Foley 2020).Although the Badtjala people won their Native Title claim, Foley says they gained very few actual rights and can’t make money from the tourism. It’s a point of ongoing frustration for Foley, who has argued for a levy to be imposed on all vehicle permits for the island, the funds of which could be reinvested in Badtjala cultural programs.

Her grandmother’s marae was at Manukorihi, (“chorus of birds” in English), an ancient pa located in northern Taranaki above the Waitara river. Famed for never being taken by another taua (invading party), the Te Ati Awa tribe commissioned a new meeting house, Te Ikaroa a Maui, with elaborate whakairo (carvings), kohaiwhari (painted carvings), and tukutuku (weavings). They debuted it with a public ceremony in 1936 when Helene’s grandmother was in her early 20s: See Figure 15.Christmas time was usually shared with extended whanau and neighbours. She prepared a gigantic Christmas family picnic. The children loaded the truck up and they trekked off to some outlying place—the bush or the lake—and dragged all the gear up there to enjoy lunch. When the parents fell asleep, the children ran riot in the bush to explore new territory.

5. Reclamations

Kim Scott’s father died in his 30s. His son said that he was not able to articulate the impact of his own experiences of colonization, but Judy Atkinson’s work in Trauma Trails: Recreating Song Lines, may be able to describe some of his experiences with collective trauma:I didn’t grow up in the bush. There was no traditional upbringing of stories around the camp fire, no earnest transmission of cultural values. The floor of the first house I remember was only partially completed, and my three siblings and I, pretending we were tightrope walkers, balanced on the floor-joints spanning the soft dirt and rubble half a metre below us.We moved to a government house on a bitumen street with gutters running down each side, and even though the street came to an end, the slope ran on and one through patchy scrub and past the superphosphate factory, the rubbish tip, the Native Reserve.Individuals were fined for being on the reserve and fined for being in town. Their crime was being non-Aboriginal in the one place and Aboriginal in the other, after legislation was refined in the attempt to snare those who—as the frustrated bureaucrat put it—“run with the hares and hunt with the hounds” and to trip them as they moved to and fro across a dividing line.My father was mobile that way, always moving

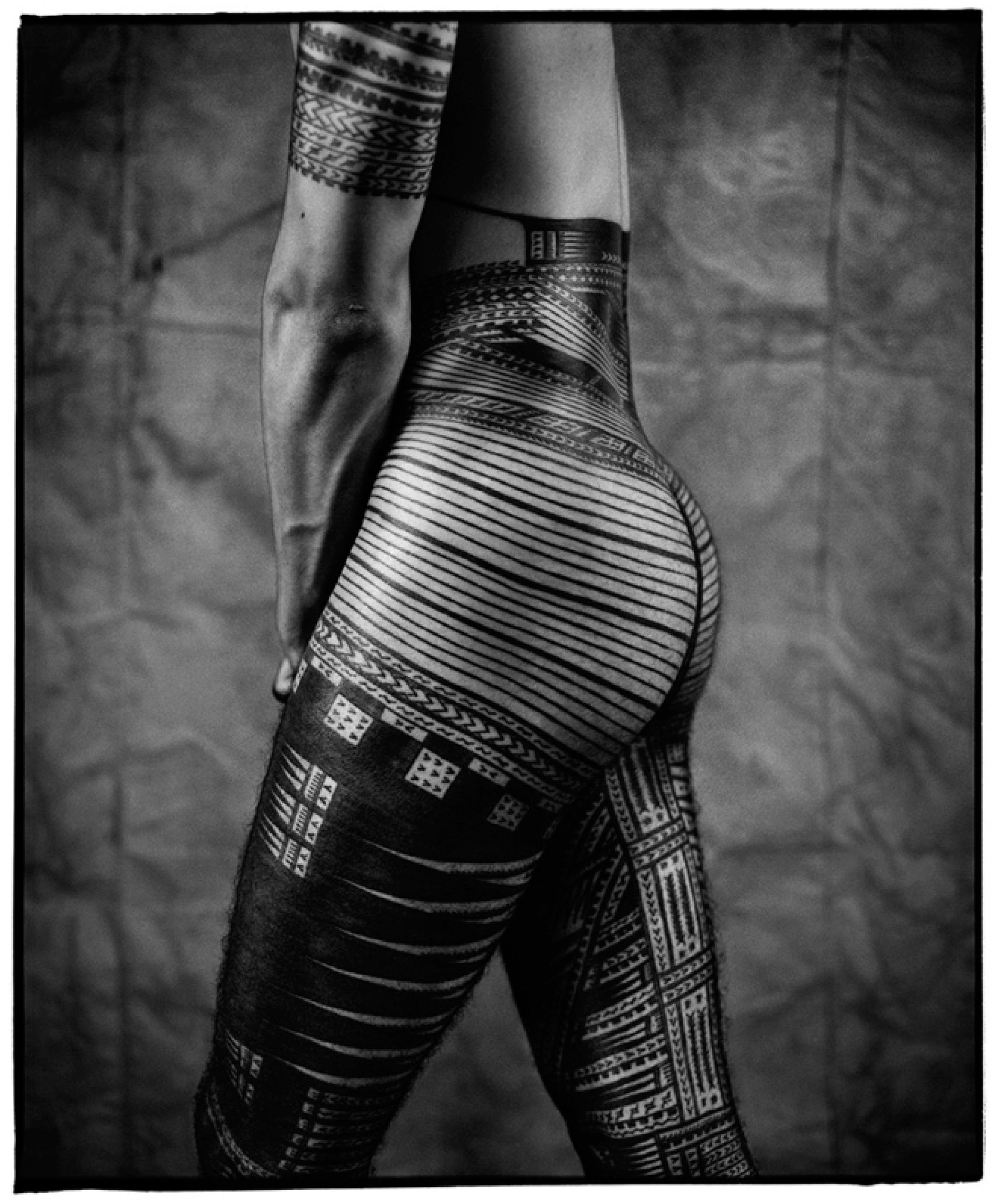

Through his commitment to understanding his family history, and learning the Noongar language, Scott has been able to reconnect to parts of his heritage that were severed. Around the world, artists, scholars, and community-based activists are reclaiming indigenous knowledges through acts of creation. The photography of Greg Semu provides one example. I first saw his work at the Queensland Museum of Art in Brisbane, Australia, in 2010. As part of UNNERVED: The New Zealand Project, he exhibited self-portraits that showed the different sides of his pe’a, the traditional men’s body tatau of Samoa. In Samoan, the verb tā means to strike, and in the case of tatau, refers to the “tap” sound of the comb used to penetrate the skin with ink. The verb tau translates as “to reach an end,” but also means war or battle. Put together, tatau also translates as “rightness” or “balance.” See Figure 16.It seeps slowly and insidiously into the fabric and soul of relationship and beliefs of people as community. The shock of loss of self and community comes gradually. People, feeling bereaved, grieve for their loss of cultural surrounds, as well as for family and friends. Feeling victimised, the same people may also carry a deep rage at what has happened to them, but may be unable to express their anger at those they perceive to have violated their world and caused the death of their loved ones

Our drawings and paintings address old (tumbuna/bipo taim) ideas, woven and marked out by a new generation of men and women from our community. We have begun telling stories through what we have seen and what we know—shields and bilum weaving. In the Highlands we are surrounded by dramatic mountains and unique beauty, made delicate by the complexities of warfare, violence and colonial presence. We compound these sometimes challenging situations through ceremonial acts of ‘bilas’ (noun: costume/verb: to beautify). Our studies into our own ancestral shields has led us as a group to understand the power of its visual language; to identify the signifiers of the tribal fight, learning from conflicts of the past in order to control forms of negativity, and come to harness the positivity of our designs for protection, and for amamas [happiness].

When we published Return to Yakni Chitto, Monique said that she wanted to honor her father’s love of their family’s traditions and his appreciation of other cultures by putting it into practice. As we talked about what the events could look like, we drew inspiration from a passage that she wrote about an afternoon in the mid-1980s when her father took her to their relatives, Jane and Anesie Verdin’s home in Pointe-aux-Chenes:In our shortcuts through back-a-town, he introduced me to his friend, John Taylor. John told me, “Everybody called your dad Julio, but I knew he wasn’t Mexican. I knew he was from the Parish. I was going into the Bayou Bienvenue swamp and bringing out garfish, and your dad was always up from down the road selling shrimp, coons, or turtle to all the Creoles who lived in the Lower Ninth Ward.” Both my dad and John were wild salesman who could see the truth. If you passed them in the street, maybe you wouldn’t think twice, but they recognized real, simple beauty from the freedom they found in that wildness.

In the Unbearable Lightness of Being, Milan Kundera writes, “The brain appears to possess a special area which we might call poetic memory and which records everything that charms or touches us, that makes our lives beautiful” (Kundera 1984, p. 208). Monique wanted to share this beauty that came from her extended Houma family with her community and the broader, diverse audiences we imagined for the book and companion exhibit. At the Neighborhood Story Project’s workshop in an old corner store building in the Seventh Ward, we hosted the exhibit and book release that emphasized leisure as “an affirmation of humanity” (Jackson 2020, p. 77). Our neighbors shucked oysters and cooked large pots of gumbo, we played bouré—a Louisiana card game—and danced. Then Monique and I packed up the exhibit and brought it down to Los Isleños Museum, dedicated to the history of Canary Islanders, to join a cross-cultural conversation about different migrations to St. Bernard Parish. See Figure 20.[W]e came up to a bunch of people gathered around a pile of freshly boiled shrimp on top of a makeshift plywood and sawhorse table, talking in Houma French. That memory stayed with me through my childhood. It was unlike other parts of the U.S. I had known. It felt like home.

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abu Lughod, Lila. 1993. Writing Women’s Worlds: Bedouin Stories. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, Kathleen M. 2006. Art as Politics: Recrafting Identities, Tourism, and Power in Tana Toraja, Indonesia. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, Sara. 2004. The Cultural Politics of Emotion. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, Judy. 2002. Trauma Trails: Reconnecting Song Lines. Melbourne: Spinifex. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, Bruce Sunpie, and Rachel Breunlin. 2019. Le Kèr Creole: Creole Compositions and Stories from Louisiana. New Orleans: University of New Orleans Press. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, Walter. 1969. The Task of the Translator in Illuminations. New York: Schocken Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bird Rose, Deborah. 2004. Reports from a Wild Country: Ethics of Decolonisation. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press. [Google Scholar]

- Breunlin, Rachel, and Maya Haviland, eds. 2008. Singing Out: Aboriginal Ladies’ Stories from the Northwest Kimberley. The Neighborhood Story Project, and Side by Side Community Projects. Derby: Jalaris Aboriginal Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Breunlin, Rachel, and Ronald W. Lewis. 2009. The House of Dance & Feathers: A Museum by Ronald W. Lewis. The Neighborhood Story Project. New Orleans: The University of New Orleans Press. [Google Scholar]

- Breunlin, Douglas, Richard Schwartz, and Betty Kune-Karrer. 2001. Metaframeworks: Transcending the Models of Family Therapy. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Bridgeman, Eric. 2020. Eric Bridgeman and Haus Yuriyal: Nene Iken Ain Ere Kole Napin/We Should Go Home. Brisbane, Australia: Milani Gallery. [Google Scholar]

- Carney, Judith. 2001. Black Rice: The African Origins in the Rice Cultivation of the Americas. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coates, Ta-Nehesi. 2013. Trayvon Martin and the Irony of American Justice. The Atlantic Monthly. July 15. Available online: https://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2013/07/trayvon-martin-and-the-irony-of-american-justice/277782/ (accessed on 1 August 2020).

- Collins, John. 2008. ‘BUT WHAT IF I SHOULD NEED TO DEFECATE IN YOUR NEIGHBORHOOD, MADAME?’ Empire, Redemption, and the ‘Tradition of the Oppressed’ in a Brazilian World Heritage Site. Cultural Anthropology 23: 279–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, Helene. 2019. Whakapapa Back: Mixed Indigenous Maori and Pakeha Heritage and Identity in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Genealogy 3: 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, Hannah. 2019. Bad luck comes, when you bulldoze boabs. National Indigenous Times. June 25. Available online: https://nit.com.au/bad-luck-comes-when-you-bulldoze-boabs/ (accessed on 26 May 2020).

- Darensbourg, Jeffery. 2018. Bulbancha is Still A Place: Decolonizing the Tricentennial of New Orleans. In Bulbancha Is Still A Place: Indigenous Culture from New Orleans. Bulbancha: POC Zine Project. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Marion. 2015. Managing a Living Cultural Landscape: Lessons and Insights from the Subaks of Bali, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Stockholm Environmental Institute. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep00442 (accessed on 2 September 2020).

- Davis, Dána-Ain, and Christa Craven. 2016. Feminist Anthropology: Thinking Through Methodologies, Challenges, and Possibilities. London: Rowman and Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Dent, Tom. 2000. Secret messages. In Literary New Orleans. Edited by Judy Long. Athens: Hill Street Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dizon, Michelle, and Viêt Lê. 2018. White Gaze. Chicago: CANDOR, Memory and Resistance Laboratory, and Sming Sming Books. [Google Scholar]

- DuBois, William Edward Burghardt. 2014. The Soul of Black Folks. Introduction by Vann Newkirk, II. New York: Restless Classics. [Google Scholar]

- Fámúle, Oláwọlé. 2018. Èdè Àyàn: The Language of Àyàn in Yòrùbá Art and Ritual of Egúngún. Yoruba Studies Review 2. Available online: https://news.clas.ufl.edu/ede-yan-the-language-of-yan-in-yoruba-art-and-ritual-of-egungun/ (accessed on 2 September 2020).

- Fields, Edda L. 2008. Deep Roots: Rice Farmers in West Africa and the African Diaspora. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Foley, Fiona. 2020. The People of K’Gari/Fraser Island: Working Through 250 Years of Racial Double Coding. Genealogy 4: 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazier, Denise. 2020. The Nickel: A History of African-Descended People in Houston, Texas. Genealogy 4: 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, Gwendolyn Midlo. 1992. Africans in Colonial Louisiana: The Development of Afro-Creole Culturel. In The Eighteenth Century. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, Faye, ed. 1991. Decolonizing Anthropology: Moving Further Towards and Anthropology for Liberation. Arlington: American Anthropological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Hartman, Saidiya. 2008. Venus in Two Acts. Small Axe 12: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, David. 2000. Spaces of Hope. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haviland, Maya. 2014. The Challenge of Cross-Cultural Creativity. In Double Desire: Transculturation and Indigenous Contemporary Art. Edited by Ian McLean. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 117–35. [Google Scholar]

- Haviland, Maya. 2017. Side by Side? Community Art and the Challenge of Co-Creativity. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, Michael. 1995. At Home in the World. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, Antoinette. 2011. Shattering Slave Life Portrayals—Uncovering Subjugated Knowledge in US Plantation Sites in South Carolina and Florida. American Anthropologist 113: 448–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, Antoinette. 2012. Speaking for the Enslaved: Heritage Interpretation at Antebellum Plantation Sites. New York: Left Coast Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, Antoinette. 2020. Heritage, Tourism, and Race: The Other Side of Leisure. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kebede, Messay. 2003. Eurocentrism and Ethiopian Historiography: Deconstructing Semitization. International Journal of Ethiopian Studies 1: 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kembrey, Melanie. 2020. Artist Fiona Foley explores how opium was used to control Aboriginal labor. The Sydney Morning Herald. January 3. Available online: https://www.smh.com.au/culture/art-and-design/artist-fiona-foley-explores-how-opium-was-used-to-control-aboriginal-labour-20191230-p53niv.html (accessed on 2 May 2020).

- Kimmerer, Robin Wall. 2013. Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Milkweed Editions. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchenblatt-Gimblett, Barbara. 2006. World Heritage and Cultural Economics. In Museum Frictions: Public Culture/Global Transformations. Edited by Ivan Karp, Corinne A. Kratz, Lynn Szwaja and Tomas Ybarra-Frausto. Durham: Duke University Press, pp. 161–202. [Google Scholar]

- Kundera, Milan. 1984. The Unbearable Lightness of Being. New York: Harper’s & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Kurutz, Steven. 2020. Ronald W. Lewis, Preserver of New Orleans Black Culture, Dies at 68. The New York Times. April 9. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/09/us/ronald-w-lewis-dead-coronavirus.html (accessed on 11 April 2020).

- McGregor, William B. 2006. Prolegomenon to a Warrwa grammar of space. In Grammars of Space: Explorations in Cognitive Diversity. Edited by Stephen C. Levinson and David P. Wilkins. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McGregor, William B. 1994. Warrwa. Munich: Languages of the World/LINCOM. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, Toni. 1987. Beloved. New York: Plume, a Division of Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, Toni. 2019. 12 of Toni Morrison’s Most Memorable Quotes: The authors thoughts on writing, freedom, identity, and more. The New York Times. August 6. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/06/books/toni-morrison-quotes.html (accessed on 10 August 2020).

- Mydans, Seth. 2007. Across Cultures, English is the Word. In The New York Times. April 9, Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2313-5778/4/3/92 (accessed on 1 September 2020).

- One Arm Point Remote Community School. 2010. Our World; Bardi Jaawi Life at Ardiyooloon. Broom: Magabala Books. [Google Scholar]

- Pai, Shin Yu. 2020. Embarkation: Reimagining a Taoist Ritual Ceremony. Genealogy 4: 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poelina, Anne. 2013. Our Nyikina Story: Australian Indigenous People of the Mardoowarra. Cultural Survival Quarterly. Available online: https://www.culturalsurvival.org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/our-nyikina-story-australian-indigenous-people-mardoowarra (accessed on 24 May 2020).

- Poelina, Anne. 2016. Blood Line, Song Line. Great Australian Story. August 12. Available online: https://greataustralianstory.com.au/story/blood-line-song-line-pt2 (accessed on 24 May 2020).

- Poelina, Anne. 2018. Mardoowarra-Fitzroy River. Water Justice Hub. Available online: https://waterjusticehub.org/mardoowarra-fitzroy-river/ (accessed on 6 August 2020).

- Povinelli, Elizabeth A. 2002. The Cunning of Recognition: Indigenous Alterities and the Making of Australian Multiculturalism. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen, Daniel. 2017. New Orleans Forgotten Slave Revolt. The Daily Beast. July 13. Available online: https://www.thedailybeast.com/new-orleans-forgotten-slave-revolt-by-dan-rasmussen-american-uprising-author (accessed on 10 August 2020).

- Regis, Helen A. 2019. Local, Native, Creole, Black: Claiming Belonging, Producing Autochthony in New Orleans. In Remaking New Orleans: Beyond Exceptionalism and Authenticity. Edited by Thomas Adams and Matt Sakakeeny. Durham: Duke University Press, pp. 138–61. [Google Scholar]

- Regis, Helen A. 2013. Producing Africa at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival. African Arts 46: 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regis, Helen A, Rachel Breunlin, and Ronald W. Lewis. 2011. Building Collaborative Partnerships Through a Lower Ninth Ward Museum. Practicing Anthropology 33: 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, Judy. 1998. Possession, Ecstasy, and Law in Ewe Voodoo. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press. [Google Scholar]

- Saunt, Claudio. 2020. Unworthy Republic: The Dispossession of Native Americans and the Road to Indian Country. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Schwab, Gabriele. 2010. Haunting Legacies: Violent Legacies and Transgenerational Trauma. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, David. 1991. That Event, This Memory: Notes on the Anthropology of African Diasporas in the New World. Diasporas: A Journal of Transnational Studies 1: 216–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, James C. 1998. Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, Kim, and Hazel Brown. 2005. Kayang and Me. Perth: Fremantle Arts Centre Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stanner, William Edward Hanley. 1979. White Man Ain’t Got No Dreaming: Essays, 1938–1973. Canberra: Australian National University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stoller, Paul. 2009. The Power of the Between: An Anthropological Odyssey. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tyquiengco, Marina. 2020. Subject to Source: Fiona Foley’s Evolving Use of Archives. Genealogy 4: 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulysses, Gina Athena. 2015. Introduction to Caribbean Rasanblaj. Emisférica 12. Available online: https://hemisphericinstitute.org/en/emisferica-121-caribbean-rasanblaj.html (accessed on 16 May 2020).

- Verdin, Monique. 2019. Return to Yakni Chitto: Houma Migrations. Edited by Rachel Breunlin with an introduction by Michael Dardar and poems by Raymond Moose Jackson. New Orleans: University of New Orleans Press. [Google Scholar]

- wa Thiongo, Ngugi. 1997. Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature. Portsmouth: Heinmann. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, Bryan. 2019. The Life and Legend of Bras Coupé: The Fugitive Slave Who Fought the Law, Ruled the Swamp, Danced at Congo Square, Invented Jazz, and Died for Love. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wegmann, Mary Ann, Louisiana State Museum, and University of New Orleans History Department. 2020. Jackson Square during the Battle of New Orleans. New Orleans Historical. Available online: https://neworleanshistorical.org/items/show/623 (accessed on 10 August 2020).

- Williams, Raymond. 1977. Marxism and Literature. Oxford: University of Oxford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Woldeyes, Yirga. 2020. ‘Holding Living Bodies in Graveyards’: The Violence of Keeping Ethiopian Manuscripts in Western Institutions. M/C Journal. Available online: http://journal.media-culture.org.au/index.php/mcjournal/article/view/1621 (accessed on 22 July 2020).

- Woldeyes, Yirga. 2019. Lalibela: Spiritual Genealogy beyond Epistemic Violence in Ethiopia. Genealogy 3: 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Breunlin, R. Decolonizing Ways of Knowing: Heritage, Living Communities, and Indigenous Understandings of Place. Genealogy 2020, 4, 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy4030095

Breunlin R. Decolonizing Ways of Knowing: Heritage, Living Communities, and Indigenous Understandings of Place. Genealogy. 2020; 4(3):95. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy4030095

Chicago/Turabian StyleBreunlin, Rachel. 2020. "Decolonizing Ways of Knowing: Heritage, Living Communities, and Indigenous Understandings of Place" Genealogy 4, no. 3: 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy4030095

APA StyleBreunlin, R. (2020). Decolonizing Ways of Knowing: Heritage, Living Communities, and Indigenous Understandings of Place. Genealogy, 4(3), 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy4030095