1. Introduction

Traditionally, identity formation, positionality, and power are explored from competing theories based on the majority White group and void of context (e.g.,

Beijaard et al. 2004;

Erickson et al. 2011;

Jenlink 2014). As

Holland and Lave (

2001) posit, individuals socially construct the essence of self through the intersectional context of figured worlds. Individuals possess distinctive ways of looking at the world, which are “socially produced, culturally constituted activities” (

Holland and Lave 2001, pp. 40–41). As such, individuals interpret the world based on unique lived cultural, historical, linguistic, and political experiences. Within figured worlds, our positionality may determine whether we are allowed into certain spaces (

Urrieta 2007a). As a dynamic process, individuals’ interpretations inform how they perceive self and others, and, in turn, this influences their experiences within their figured worlds. In the case of Latinos or Mexican Americans, our identities, histories, positionality, and power are also intimately linked and reflective of what

Anzaldúa (

1997) calls the “consciousness of the borderlands” (p. 270). Additionally, our identities are a fusion of various racial groups that the philosopher

Vasconcelos (

2013) referred to as

La Raza Cosmica. To explore self within figured multiple worlds, both physical and metaphysical, in contrast to traditional autobiographic methods,

Anzaldúa and Keating’s (

2009)

autohistoria as a decolonial methodology is appropriate.

Autohistoria, in contrast to storytelling, creates a tapestry of our stories with those of our

antepasados, while prompting critical reflection of the sociocultural, historical, and political contexts.

Undeniably, engaging in

autohistoria of our figured worlds is critical, given that the current sociopolitical context perpetuates a “culture of forgetting” (

Darder 2017), which results in the shedding of the ethnic/cultural/linguistic/historical self. As

Flores and Clark (

2017) demonstrate, educators’ identities are awakened when they examine and interrogate how their identities, beliefs, positionalities, and consciousness were influenced by various experiences. According to

Freire (

1993), the discovery of self becomes a liberatory act that heightens our

concientización (critical consciousness). Thus, the exploration of self within the sociocultural, historical, political context is paramount (

Flores and Clark 2017;

Gómez et al. 2008;

Sleeter 2008) and is ongoing process (

Flores and Clark 2017;

Urrieta 2007b).

Towards this end, I am using

autohistoria-teoria (

Anzaldúa 1987) methodology and

Holland and Lave’s (

2001) notion of figured worlds, as a sociocultural, historical, and political space in which individuals configure self, to explore and share my paternal grandmother’s family,

Los Martínez’, cultural-historical experiences. In particular, I explore, as figured worlds, various border crossings, whether across land, rivers, or oceans, and other geographic spaces. Specifically, I consider the uniqueness of the US Texas-Mexico border as a historical, political, and ever-present context as a figured world influencing the essence of the individual. The following question guides my

autohistoria: How does cultural-historical experiences along borders shape identities, positionalities, and power in the spaces we occupy?

As colonizers and settlers,

Los Martínez’ lived along the Rio Grande-Río Bravo de Norte

1, which is now the Texas and Mexico border, and these experiences will serve as the narrative case-study. Yet, their story begins across the Atlantic in the Kingdom of Navarre, presently in northern Spain. As such, my analysis considers

Urrieta’s (

2007a) proclamation:

… in figured worlds people encounter narratives borne out of historical significance (both oppressive and liberating) as well as a distribution of power, rank, and prestige (or the lack thereof) that they either accept, reject, or negotiate to varying degree.

(p. 111)

Using archival data interwoven with historical events, spanning from the 14th century to present, these themes are revealed:

Situational identities, positionality, and power (circa 14th–15th centuries);

Renegotiated identities, positionality, and power (circa 15th–17th centuries);

Reconstituted identities, positionality, and power (circa 17th–19th centuries);

Repatriated identities, positionality, and power (circa 19th–20th centuries); and

Revitalized identities, privilege, and power (circa 21st century).

Each of these themes will be elaborated in the subsequent paragraphs and will be followed by a discussion and conclusion.

2. Results

2.1. Situational Identities, Positionality, and Power (Circa 14th–Mid 15th Centuries)

In examining the ancestral origins of

Los Martínez, the theme of situational identities, positionality, and power were derived from my

antepasados’ figured world, the royal court in the Middle Ages. During this period, status was predetermined based on class structures, and education was limited to the ruling and noble classes as well as clergy; e.g., bishops, priests, and nuns (

Kersey 1980). Hence, identity, positionality, and power were determined based on the situation of a person’s birth, or birthright.

In traversing back through time in search of my historical ancestry, I learned that my 14th great grandmother, Catalina Sánchiz de Lizaso, was the mistress of King Charles II “the Bad” d’Evreux De Navarre in 1375 (

Cawley 2019a). The Kingdom of Navarre was located in the western Pyrenes, what we now consider northern Spain, but during the Middle Ages it was ruled by the French monarchies (

Narbona-Cárceles 2001). While the historical accounts of Charles II are well documented, little is known about Catalina and her family. Catalina was born in 1350, the daughter of Iñigo O. Yenego Sánchiz, Abad de Lizaso (

Cawley 2019b); the title of Abad indicates that her father was a priest. While bishops lived lavishly and owned property, priests did not attain such wealth; nevertheless, they were afforded certain privileges (

Kersey 1980). Given that Catalina’s father was an Abad, she was likely given opportunities to learn literacy skills in Latin and the social skills needed to be part of the royal court (

Kersey 1980). Further, Catalina’s identity and positionality, as revealed in historical documents, were linked to the recognition that she was identified as a woman of the royal court (

Narbona-Cárceles 2001).

After Queen Joan of Valois’ died in 1373, Catalina positionality was changed and situated based on how others perceived her status. Perhaps Catalina was a lady in waiting for Queen Joan (Jeanne) of Valois’ in Navarre. As a lady in waiting, Catalina would have assisted the queen, but may have also been expected to engage in sexual services to the king. Catalina had presence in the court and likely captured the eye of the king. Interestingly, genealogy ancestry documents from the Netherlands recognize Catalina as a legitimate spouse of Charles the Bad. In Spanish historical documents, she is not recognized, or simply identified as his mistress (

Cawley 2019a;

Yanguas y Miranda 1840). These distinct views of Catalina’s positionality may reflect cultural and religious differences of the historians documenting this period of time.

Catalina bore two children, Leonel Mosen Evreux Batard (1378–1413) and Blanca Joanna Evereuz Batard (b. 1385). Leonel’s and Blanca’s lineage are confirmed in charter documents dated 1380, in which Charles provided financial support for his children (

Cawley 2019b;

Yanguas y Miranda 1840). After Charles II’s death, historical documents reveal that Catalina continued to receive financial support from the kingdom (

Yanguas y Miranda 1840). For the purpose of this

autohistoria narrative, I followed Leonel Mosen’s historical journey, as he is my direct ancestor. In 1407, Charles III, King of Navarre, bestowed his step-brother, Leonel Mosen, the title of Vizcondes de Muruzábal, Marqueses de Cortes (

Cawley 2019b).

In 1388, Catalina died when she was 38. Given Catalina’s status within the kingdom, her children’s titles clearly identified their illegitimacy at birth, yet she and her children were provided financial support and her son was afforded an education. With the awarding of a prestigious, noble title, Leonel’s situational identity, positionality, and symbolic power were being transformed; he was no longer just the bastard son of Charles II. While he had no right to become king, Leonel nevertheless was recognized as a son and his descendants likely benefited from this ascribed noble status.

Leonel’s son, my 13th great grandfather, Felipe Batard, 2nd Vizcondes de Murazabal de Navarre (1410–1450), was also recognized as a nephew by the court. This claim is based on marriage and historical documents (

Cawley 2019b,

2019c). Carlos III gave 3500

florinos for the marriage of Felipe (

su subrino) and Juana de Peralta y Ezpeleta, daughter of Baron Mosen Pierres de Peralta, who was also the maestrehostal (palace manager). Their son Pedro de Navarro (b. 1442), my 12th great grandfather, was named the 3rd Vizcondes de Murazabal (

Cawley 2019b;

Dynastie Capetienne 2020;

Cadenas y Vicent 1992). Don Juan Pedro de Navarro married María Isabela Rodríguez de Peralta (1449–1536), likely his cousin, from the Peralta noble family.

Catalina and her descendants’ identities as to how they saw themselves, their positionality as to how others perceived them, and what power they had afforded to them was based on their role and status in the court. Over time, situational identities, positionality, and power were being altered as the family’s noble status was affirmed with the awarding of titles and lands. Further, marital alliances with other royal families secured and ensured their status.

2.2. Renegotiated Identities, Positionality, and Power (Circa 15th–17th Centuries)

The theme of renegotiated identities, positionality, and power is evident in that Catalina’s descendants’ status was no longer tied to her situational circumstances or the social constraints of her birthright. I suggest that renegotiation occurs when individuals convert their identities and ascribed status, which is based on social constraints, through self-determination or transactions that result in the socially significant forms of power, such as the procurement of wealth. The attainment of titles and lands allowed for Catalina’s descendants to identify as members of the royal class, transform how they were perceived, and the power they held within their figured worlds. Thus, upon arrival to Nuevo España, this renegotiated identities and status afforded Catalina’s descendants’ privilege and power.

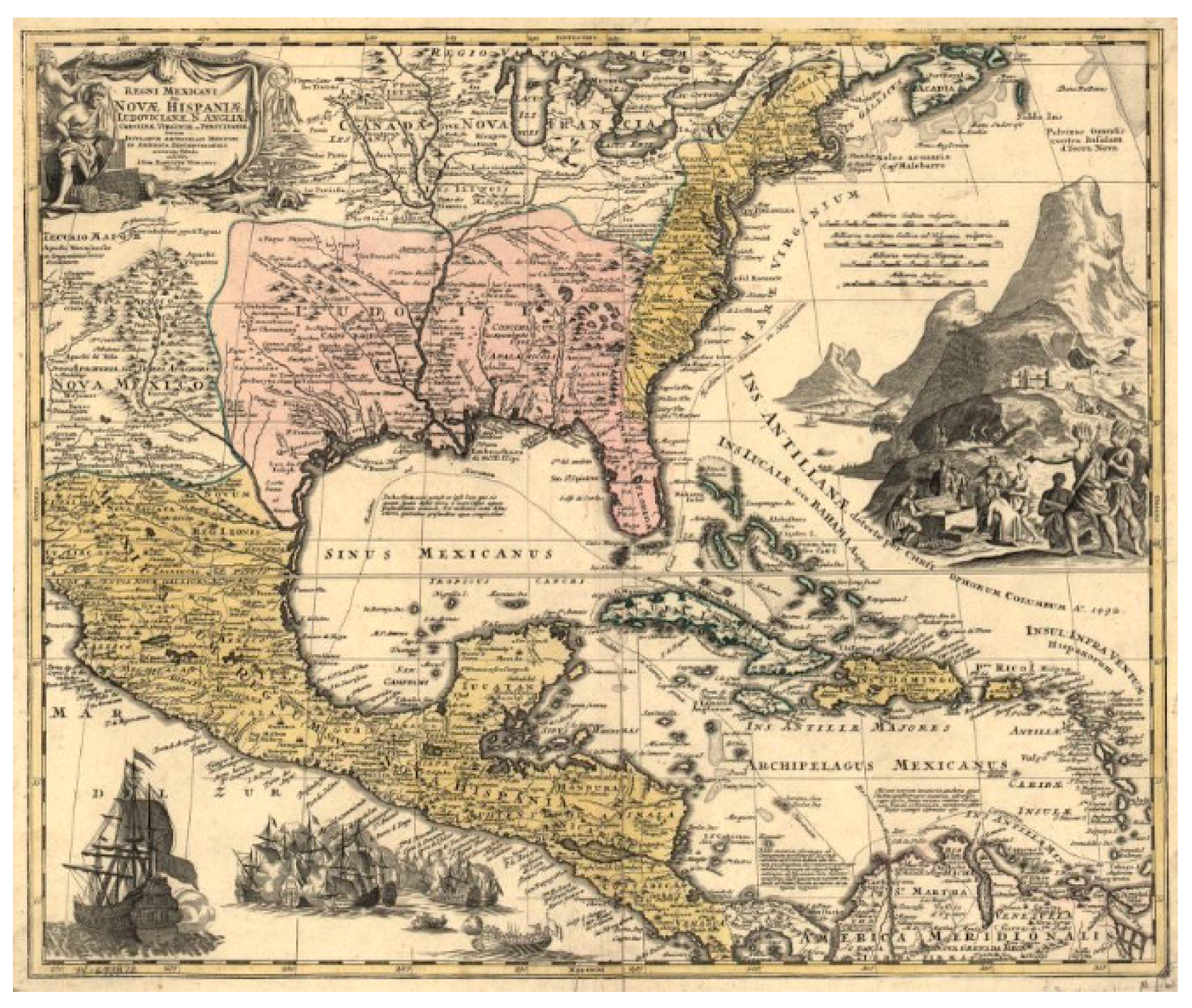

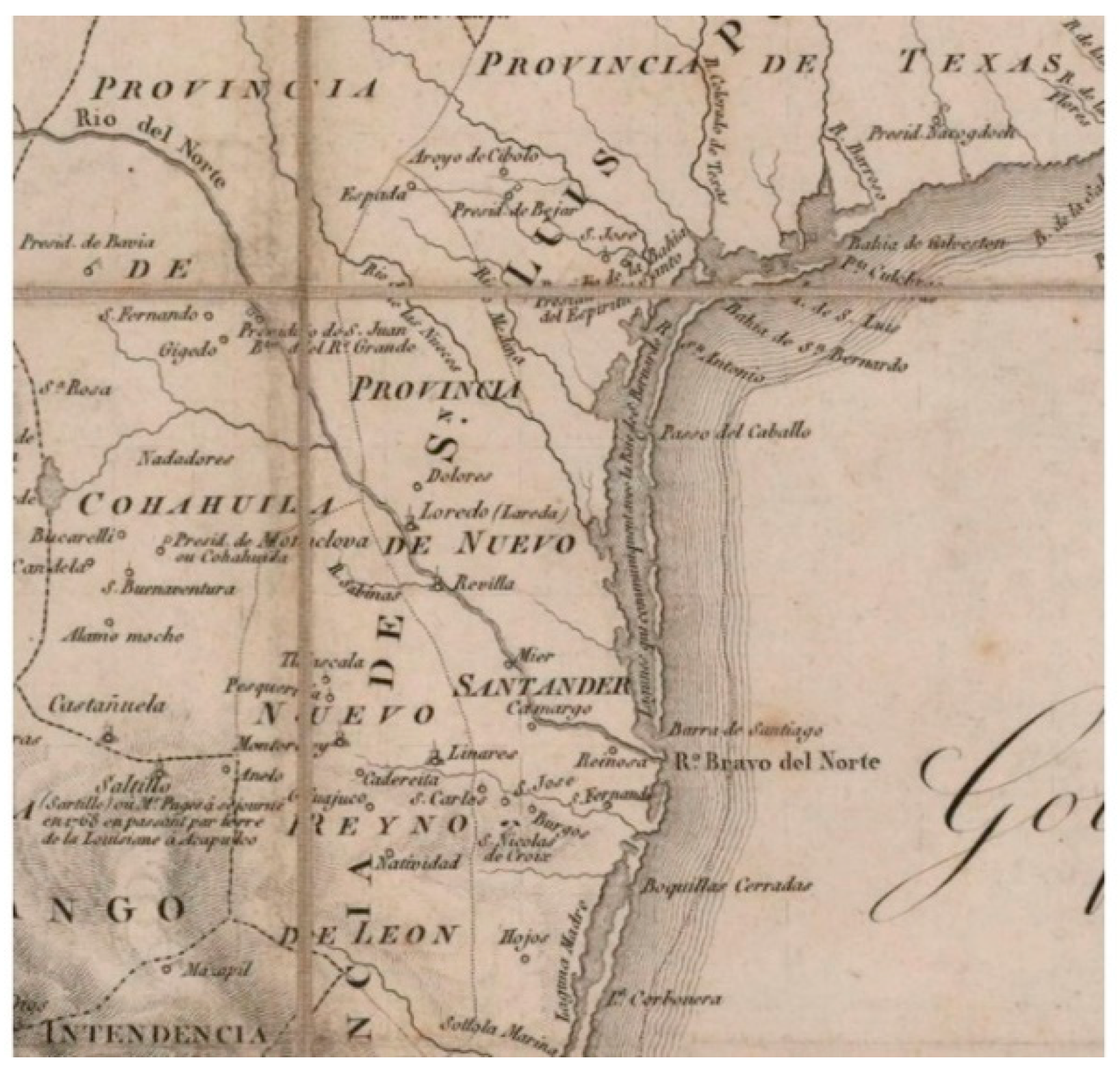

In following Catalina’s descendants’ journeys, it was evident that they were conquerors who proclaimed the “discovered” new world for Spain. From 1519–1685; 1690–1821, Spain ruled

Nuevo España, which included Texas (see

Figure 1: Nuevo España Map (

Anville et al. 1979) &

Figure 2:

van Humbolt (1811) Texas Map

2; see

Figure S2 van Humbolt Interactive Map). The French occupied the region from 1684–1690.

In securing these lands for Spain, the

conquistadores had the positionality and power to rule over these new figured worlds. Don Juan Pedro and María Isabela’s son, Capítan Juan Pedro Navarro II (1488–1536), my 11th great grandfather, was a conquistador. His spouse was María de Navarre Sosa (1491–1555). He attained a military title and it is suggested that as a conquistador, he traveled to the new world first to arrest Cortez and then assisted Cortez with

la conquista. As part of a Spanish land grant (

encomienda), he was awarded the Sierra Mazateca, Teotitlán, and La Cañada in what is now considered southern México (

Feinberg 2003;

Icazbalceta and García Pimentel 1904).

Juan Pedro II and María de Navarre Sosa’s son, Capítan Juan Pedro Navarro III (1533–1594), my 10th great grandfather, was born in Spain, and arrived in the new world with titles and wealth. He was a conquistador procuring additional land and wealth, as well as power. Essentially, Capítan Juan Pedro Navarro III was part of Nuevo España’s gentile, noble class. He married María Rodríguez Castaño de Sosa, born in 1565 in Monterrey, México (Nuevo España), the daughter of Baltazar Castaño de Sosa (1537–1595), who in 1583 became the mayor of Saltillo, Coahuila, Nuevo España.

Juan Pedro and María’s daughter, my 9th great grandmother, Ursula Inés Catarina Navarro Rodríguez (~1581–1640) was born in Monterrey, México and married to Capítan Juan Francisco Martínez Guajardo (~1565–1613). As military officers, my conquistador antepasados’ identity was tied to their status, and they held both position and power in their figured world, which thus afforded and legitimized their families’ elite status in Nuevo España.

During this era, more of my

antepasados were being born in

Nuevo España; thereby, perhaps the forging of a new identity was occurring. The descendants of Ursula and Capítan Juan Francisco became the settlers of northern Nuevo España, establishing villas along the north corridor towards the Río Bravo/Grande (

Inclán 2009). Their son, my 8th great grandfather, Capítan José Ignacio Martínez-Guajardo (~1600–1654), was born in Santiago de Saltillo, Coahuila, México and married María Isabela Flores de Valdez, born around 1600 in Saltillo, Coahuila. Their second son, my 7th great grandfather, Capítan José Ignacio Martínez Flores (1652–1712), and Inés de la Garza (1653–1734) were married in Monterrey in 1683. He founded the Hacienda San Antonio de Los Martínez in 1684, which later become the Villa de San Carlos de Marín (

Farías and Martínez 2011;

Inclán 2009).

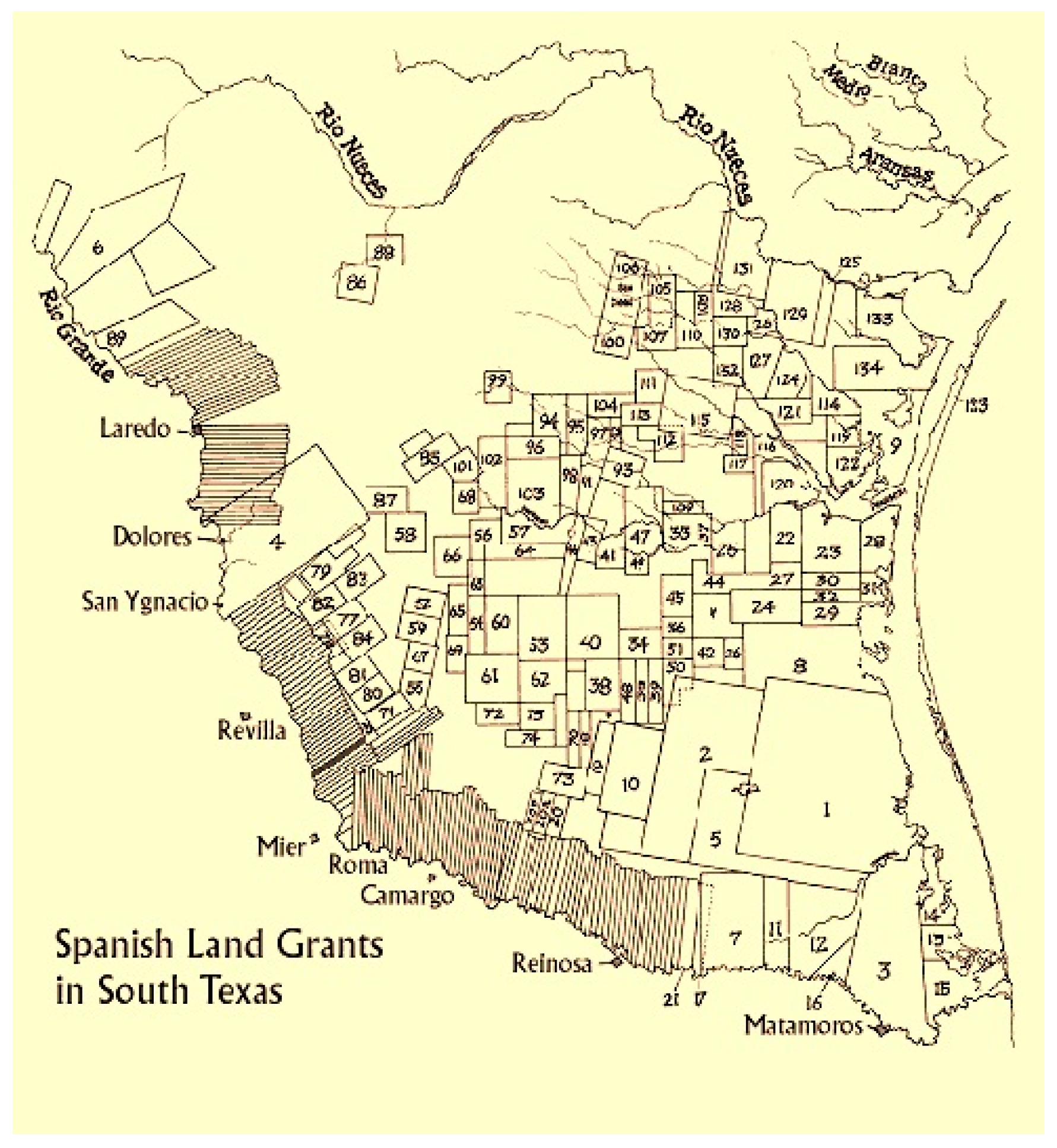

Capítan José Ignacio and Inés’ son, Alférez (high ranking officer) Miguel Martínez (1674–1759), my 6th grandfather, and his spouse, Clara Treviño Rentería (1674–1774) in 1753 received Spanish land grant

porcion #55 as one of the original settlers of Revilla, which was part of

Nuevo Santander. In an effort to ensure Spain’s stronghold of the Sierra Gorda region, José de Escandón led the colonization of Nuevo Santander, an area located between Cerralvo and the Río Bravo, which included Revilla ((

De la Peña 1995;

Lang and Long 20163); see

Figure 3: Spanish Land Grants Map, (

Jackson 1986)).

Revilla (later named Cuidad Guerrero) flourished as the 43 original families grew (

Peña 2006), and often cousins married cousins, as is evident in my paternal family tree.

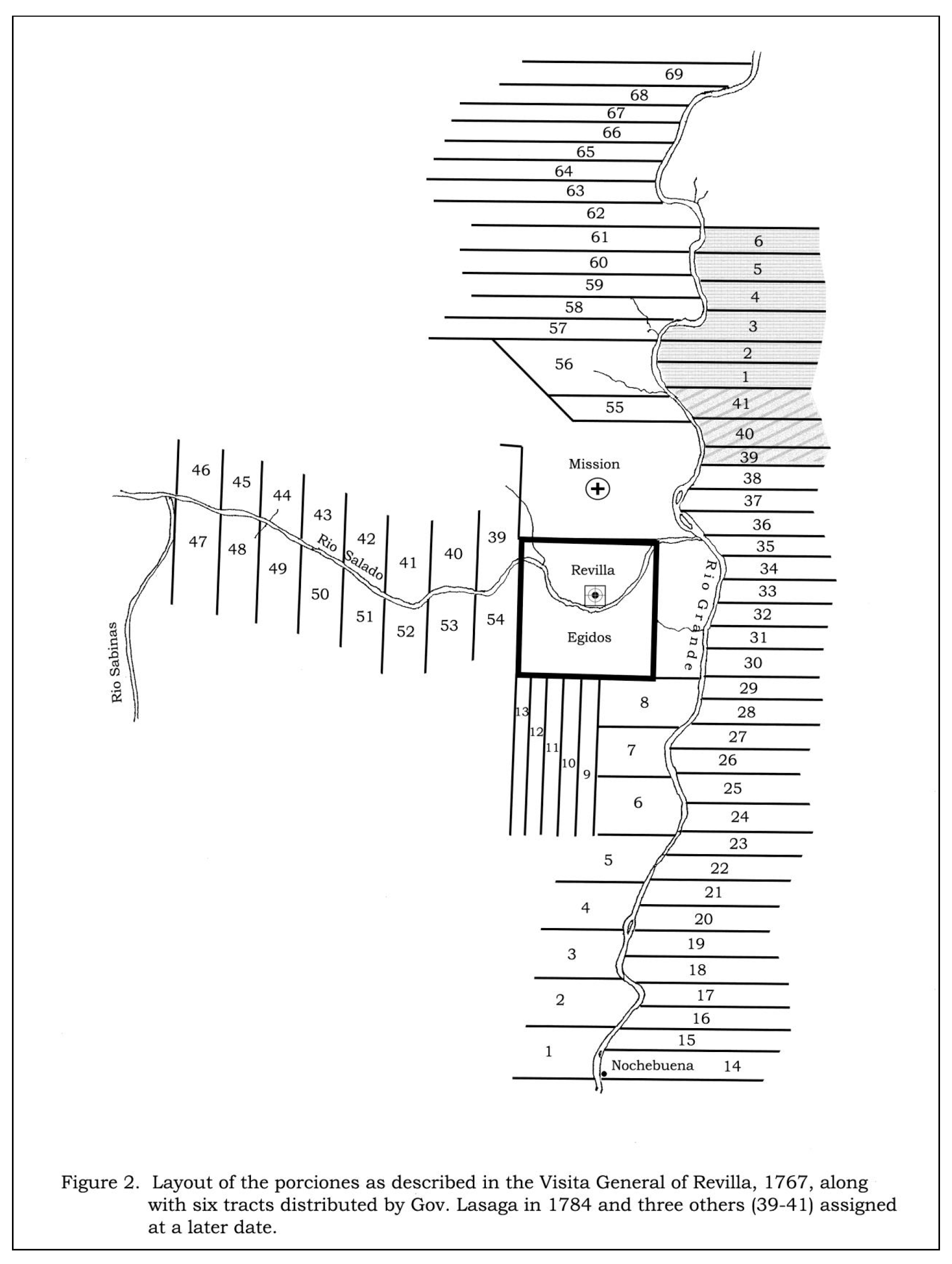

Los Martínez de Revilla were listed in the 1757 Mexican Census and included Miguel, Clara, and their direct descendants. In 1767, their descendants, including my 5th great grandfather, José Bartolomé Martínez (1733–1804), who married María Gertrudis García (~1735–1821), received a distribution of the Spanish land grant “porciones” #56 ((

De la Peña 1995;

Farías and Martínez 2011); see

Figure 4: Revilla Porciones Map, (

Greaser et al. 2009)). An examination of Revilla records reveals that cousins were marrying cousins and that sometimes the couple had to ask the Catholic church for matrimonial dispensations; hence both paternal and maternal families carried the Martínez last name.

Los Martínez left Revilla at different points, some left to

El Rancho Martineño (

Martínez y Martínez 1978). My father, Arturo S. Bustos, recalls his Tío José María speaking fondly of our

antepasados living in El Martineño, La Palma (near el Río Salado), and El Uribeño. In examining historical geographic maps of the locations of these areas, El Uribeño existed in the present Zapata County, Texas (

Martínez y Martínez 1978;

De la Peña 1995).

Franciscan missions flourished in Nuevo Santander, which promoted the practice of Catholicism and the conversions of the native people (

Peña 2006). The priests kept detailed records of marriages, births, and deaths. As I examined these documents, the records clearly reflect the Spanish

Casta (lineage/breed) system, as individuals were identified as Castellanos (Spanish), chinos, criollo, mestizos, mulatos, negros, indio, zorros, etc. The names and origins of those in attendance or serving as witnesses at various events were also recorded, which helped preserve the history of the era, but also the status quo. Those who were

Castellanos had a Spanish identity, and as their blood was not tainted,

sangre pura, they were perceived to have greater positionality and power (

Martínez 2010). On my paternal side, my documents do not reveal any familial allegiance to the French language or culture, even though France occupied México from 1684–1690. However, yet again, it is important to consider that some of our Mexican cultural practices, such as Mariachi music, cascarones, and piñatas, may indeed have French influence.

2.3. Reconstituted Identities, Positionality, and Power (Circa 18th–19th Centuries)

The third theme of reconstituted identities, positionality, and power signify a shift or the formation of new identities and status. As more families were born in México, according to my Tío José María, there was shift of loyalty from the madre patria (mother country). The Spanish-origin families did not appreciate having to pay tribute to the Spanish crown. Eventually, after México won its independence in 1821 from Spain, the emergence of this third theme was evident. Los Martínez, like other families of Spanish-origin, were no longer intimately tied to a Spanish identity, and while the majority were classified as Castellanos, there was a new reconstituted identity and positionality being formed in the new figured world, as Mexicanos.

The country occupying and ruling the new lands in the Americas held the upper hand, the power in controlling the destiny of the people, and, as such, impacted the formation of a new identity and positionality. Much history has been written about the countries or groups that have ruled over Texas (

Fehrenbach 2014). However, before Spain claimed ownership over Texas and other territories, the Americas and, more specifically, the lands along the Río Bravo, were indigenous. Tío José María (

Martínez y Martínez 1978) reflected on the conflicts between the settlers and the indigenous groups residing along the Río Bravo.

Martínez y Martínez (

1978) reveals that two of our ancestral great grandfathers, Claudio Gutiérrez Gutiérrez, (1802–1835) living in

El Uribeno and José Manuel Nepomuceno Martínez (1813–1843) living in

El Rancho La Palma, were murdered by “

indios malditos” (savage Indians; pp. 104–5).

According to

Peña (

2006), around 60 various native tribes resided in El Seno, México, and northern territories. While some indigenous tribes assisted the settlers in adjusting to life in the new lands, others, such as the Apache and Commanche, did not welcome these invaders or their diseases (

Peña 2006).

Los Martínez had acquired land grants as conqueror-settlers, which sustained their positionality and power as landowners of indigenous spaces, while systematically displacing the native population. Meanwhile, in Texas, a revolution was brewing, which resulted in the conqueror becoming conquered.

As a result of the Texas Revolutionary War with México, in 1836, Texas became a republic. Then, in 1845, Texas joined the United States. However, México did not recognize the treaty and viewed the US as encroaching on its northern lands. My Tío José María (

Martínez y Martínez 1978) reflected, “En esos lejanos y difíciles días nuestra Patria era extensa, virgen. Todavía los norteamericanos no la mutilaban” ([In those difficult days of long ago, our Mother country was extensive, virgin lands. The North Americans had not yet mutilated her], p. 105). My Tío likely saw the invasion of the US on the Mexican northern lands as a loss of positionality of the mother country and of the

Mexicano. Similarly,

Vasconcelos’ (

2013) personal experiences, as a child living along the border and attending school in Eagle Pass, Texas in which he observed the discriminatory practices against

Mexicanos, led him to pronounce that “ideologically, the Anglos continue to conquer us” (p. 403).

The US justified their actions through a belief in “manifest destiny”, a divine right to expand westward and conquer the land and the people residing in these territories, which included Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, Texas, and Utah. At the end of the Mexican–American War, in 1848, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed, wherein México ceded claims to its territories north of the Río Bravo. In 1861, Texas seceded from the United States and became part of the Confederate States of America, and after the Civil War rejoined the Union in 1865 (

Texas State Historical Association [TSHA] 2020). Depending on which side of the border

Los Martínez’ were residing, their identity, positionality, and power likely reflected the reconstituting and colliding of these cultural, linguistic, geographic, historical, and political figured worlds.

2.4. Repatriated Identities, Positionality, and Power (Circa 19th–20th Centuries)

With the formation of Texas as a republic and the Mexican Revolutionary war, the theme of repatriated identities, positionality, and power was noted. Repatriation occurs when an individual’s citizenship and birthright are transformed either voluntarily or involuntarily depending on those in power. In the case of

Los Martínez, my paternal great grandparents, living in the early- to mid-1800s, were residing on both sides of the Río Bravo (Grande). Some were living in Revilla, like my 3rd great grandfather, José Manuel Nepomuceno Martínez (1813–1843), who was Catalina’s descendant, whereas José María Antonio Eduardo Martínez (1821), a sheep rancher, had a Spanish land grant and owned

El Ranche de los Martínez4 located within the Texas border. The 1880 US Census documents that he, his wife, María de Loreto Ramirez Martínez (1824–1909), and the members of their family were living in

El Ranche de los Martínez, which appeared to be part of

Los Ovejas Rancho.

Interestingly, even though some of my great grandparents’ children and grandchildren were born after 1848, the Census birthplace location was identified as México. Based on the birthdates, I wondered if indeed they were born in México or in Texas. Since Texas became part of the United States in 1848, they should have also been considered US citizens, as per the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Perhaps, their identities were tied to México and since their land was once part of México, the family did not identify as US citizens. This may also be a sign of resistance to subjugation.

Also residing in

El Ranche de los Martínez, Texas was my great, great grandfather, José Reyes Martínez (1854–1943) and his wife, Juana M. Martinez, (1861–1947), a descendent of Catalina. Around 1872, Papa Reyitos, Juana, and other family members crossed the Rio Grande from Texas into México to find land for grazing sheep (

Martínez y Martínez 1978). Again, I wonder if other factors came into play when Papá Reyitos decided to move the family. According to

Montejano (

1987), the Texas Revolution led to the loss of lands owned by Mexican ranchers and the segregation of the Mexican population and their descendants. Hence, within this figured world, power was now held by the Republic of Texas and later the US, which resulted in a loss of positionality and power for

Mexicano families living along the border. In crossing the border, Papa Reyitos was repatriated to his country of origin.

Papá Reyitos was one of the original settlers of San Ignacio, Tamaulipas, México (

Martínez y Martínez 1978). During the Mexican Revolutionary War (1910–1920), his daughter, María del Socorro Martínez de Martínez (1880–1963), her husband, a descendent of Catalina, Jesus María Martínez (1860–1957), and their family again crossed the Río Bravo back into Texas.

Sosa and Neftalí (

2013) document that the Mexican Revolution drove many families to come to the US to escape the cruelties of war

5. Jesús María Martinez’s daughter, like other children of the revolution, Juliana Martínez (1916–2012), my paternal grandmother, was born in San Ygnacio, Texas located on the Rio Grande and across from San Ignacio, México. When the war was over, the family returned to San Ignacio, México. Again, here we observe the repatriation of identities, positionalities, and power, with some families remaining in the US and others choosing to return to México. Also evident is the fluidity of the border, in which movement occurred freely across the Río Bravo (Grande).

Even though Mamá Julia and her older brother, Feliciano (1913–1999) were born in Texas, it is clear that the family identified as Mexicanos and that their ownership of land as descendants of the original settlers of San Ignacio represented their positionality and power within that community. Mamá Julia would tell me how much she loved el Rancho de San Ignacio. She also shared wonderful stories of my grandfather, Arturo Silvano Bustos, whom she met while he was patrolling the border, “montado en un caballo blanco” (mounted on white horse). They married in 1935 at El Rancho de San Ignacio. The marriage did not last because Mamá Julia did not like the idea of living in a big city versus living the simple of life of the rancho. “Yo me quiera quedarme en mi rancho, y Arturo, tu abuelo, era de la capital”, so she stayed on el rancho. My father, Arturo Silvano Bustos, Jr. (1935) was born in San Ignacio, México.

While living in the rancho, under the tutelage of her brother José María Martínez y Martínez, Mamá Julia earned her credentials as a maestra/normalista rural (teacher). One of my favorite family pictures of Mamá Julia is one in which she is smiling and standing in front of a rural school adobe building with her class. As a child, my father also attended the school. Eventually Mamá Julia remarried, and in 1948 she moved with her son, Arturo, to San Antonio, Texas.

When San Ignacio was flooded due to torrential rains and the establishment of the Falcon Lake, the majority of the family left for Nuevo Laredo, México (

Martínez y Martínez 1978). After the water receded,

El Rancho de San Ignacio became a family getaway. As a child, I also have fond memories of San Ignacio—sleeping under the cool air coming from the Río Bravo and playing in the hot sun. I remember my Tío José María sharing the stories of our great grandparents and other relatives living in

El Rancho de San Ignacio. With pride, he would show us around the abandoned town where Pancho Villa once had a gun fight and the tree that still had his bullet in its trunk. From the Mexican perspective, Pancho Villa is seen as a revolutionary hero much like Robin Hood, whereas from US historical accounts, Villa is seen as ruthless bandit because he dared to “attack” the US border (

Katz 1998).

During our visits, Tío José María and my Mamá Julia would also introduce us to other

primos (cousins) or

tíos (uncles) still residing in San Ignacio and the school building where he, Mamá Julia, and other family members were teachers. They would recount historical events and hardships as we walked through

Los Martínez’ family cemetery site. They would say “

Estos son nuestros antepasados, que en paz descansen, sin por ellos y su sacrificio en esos tiempos, no estuviéramos aquí” (These are our ancestors, that they may rest in peace; if it was not for their sacrifices, none of us would be here). They would also share with humility and sadness that our

antepasados also lived in Revilla (Guerrero Viejo), where their graves were underwater due to the building of the Falcon Dam in 1953. Tío José also spoke about the greater good in the building of the dam and how others families were uprooted to Nueva Cuidad Guerrero (

Martínez y Martínez 1978;

Peña 2006). We were also reminded that we had

primos and

tios living in San Ygancio and Laredo, Texas.

When traveling in México, my family was seen as privileged “Americanos”, gringos (pejorative term for US foreigner or a person of Latino descent that no longer can speak Spanish), or pochos (pejorative term to convey abandonment of México and inability to speak “correct” Spanish). I recall that I did not appreciate being considered a gringa or pocha because, after all, I had been raised to be proud of my bicultural, historical, and bilingual heritage. As I now reflect, perhaps, we were seen as privileged because our positionality was also tied to our antepasados’ status.

These historical and personal accounts demonstrate the repatriation of identities, positionality, and power. Some of Los Martínez either chose or were driven back into México once the Texas Revolutionary War ended, others chose to stay in Texas. Then, during the Mexican Revolutionary War, Los Martínez residing in San Ignacio were driven back into Texas. What is also observed is the fluidity of the border, with families moving across the Río Bravo/Grande dependent on the threat of war or in search for a better life.

2.5. Revitalized Identities, Privilege, and Power (21st Century)

In the most current century, the theme of revitalized identities, privilege, and power has surfaced in exploring Los Martínez’ descendants. Revitalization occurs when individuals resist subjugation, oppression, and/or hegemonic discourse. Rather than succumbing to such oppressive hegemonic discourse, my family chose to instill a sense of cultural and linguistic wealth.

As a descendent of Los Martínez, I am proud to be a bicultural-bilingual Mexican American. I am privileged, as I have obtained a terminal degree and I am an academic. I am also privileged in that I have power as an associate dean. However, these achievements were the result of personal attainment, despite some oppressive experiences, and much support from my family. When I consider my success, I think about my initial experiences as a bicultural-bilingual child and how these experiences built my view of the world and my resistance towards pejorative majoritarian tales about my identities, biculturalism, and bilingualism.

As a child, my Mamá Julia was most ardent that her grandchildren be bilingual. She would say, “la persona bilingüe, vale por dos” (a bilingual is worth two people). She and I would spend time together when my mother, Frances Salazar Bustos (b. 1934) was at work. Mamá Julia taught me how to read and write in Spanish; she would have me read religious pamphlets and we would study human anatomy in Spanish. During these times, she would tell me cuentos about her adventures en la rancho and other children’s stories.

My mother, Frances, always encouraged me to be an independent thinker, not to allow others to make me feel less than (

“no te dejes”) and to be proud of our familial roots. She also taught me how to cook and sew, involved me in girl scouts, took me to cooking activities or swimming lessons sponsored by the city, and also made sure I took piano lessons. Activities such as cooking, sewing, and music supported my mathematical and logical thinking (

Riojas-Cortez et al. 2008). Through

consejos (advice) and

dichos (sayings), she taught me that a successful woman can be smart and accomplished.

My father also provided experiences that allowed me to think mathematically, whether it was measuring a room or calculating the mileage on a family trip. He also would encourage my siblings and I to study and stay in school so that we could have professional jobs and become respected members of the community. He would say “Fíjense como la gente respetan a tu Tío José María, siempre lo saludan, Licenciado, Director, o Profesor” (See how the people in the community respect your Tío José María; they always formally greet him as a licensed educator, principal, or professor).

My parents’ experiences growing up in the US reflected the prejudice and discrimination towards Mexican Americans during the mid-1930s, in which Mexicans and their descendants were thought of as being dirty, disease-carrying, and backward (

Montejano 1987). My mother Frances recounted her father’s experience as a sharecropper and how she and her family were treated as second-class citizens. In Seguin, my mother recalled that there was a lot of prejudice against Mexican Americans; this is ironic because it bears the name of Juan Seguin, a hero of the Texas Revolution. She also shared how her brother, Tío Epifaño, upon his return from the war, dressed in full uniform and bearing his purple star medal, experienced discrimination in Seguin, Texas when he was refused service at a restaurant. During the mid-20th century, Jim Crow laws allowed lawful discrimination and promoted the segregation of Mexicans and African Americans (

Montejano 1987). Signage such as “We serve Whites only. No dogs or Mexicans!” were proudly displayed in places of business and persisted throughout Texas until the mid-1940s (see

Figure 5: Segregation Signage as captured by

Lee n.d.).

Jim Crow Laws ensured the positionality and power of the Whites, mostly Anglo Texans, while subjugating Mexicans, Mexican Americans, and African Americans through inadequate, segregated schooling, as well as limiting their access to services and voting rights. These insidious practices ensured that Mexicans’ and their descendants’ positionality was that of second-class citizens who would never attain any power.

As a result, individuals did not know their rights or expect that the laws would protect their rights as citizens. My father, Arturo, would silently express concern that he would be deported because he was born in México when, in fact, he had citizenship rights because his mother had been born in Texas. I recall a trip to California when I was an adolescent when a border patrol pulled over my father asking him for proof of citizenship. Fortunately, my mother had our birth certificates and my father had his “migra” (immigration) card from when he had crossed the border as an adolescent. Once the border patrol learned that in fact my father’s mother (Mamá Julia) was born in Texas and that all of us were born in Texas, he told my dad to take care of his citizenship upon his return to San Antonio, Texas. It was then that my father learned that he did not need an immigration card because he had full citizenship rights. Beyond that, he had ancestral claims; Los Martínez at different points in time had resided in Texas.

Despite my parents’ experiences, they were determined that their children have greater educational and economic opportunities, so rather than sending us to the barrio school, they made a decision to send us to Catholic school. Because of my mother’s segregated schooling experiences, my parents knew that the barrio school did not afford the best educational opportunities. From first to eighth grade, I attended a small Catholic school, which served a predominantly Mexican American community. When I completed eighth grade, my father indicated that either I would continue my education in a Catholic high school or that we would move to a better neighborhood.

My father was forward-thinking—he also wanted me to learn the home-purchasing process, so I went house hunting with my parents. I clearly remember my parents’ experience in their attempt to purchase a new home. During one of these times, I could tell the realtor was not interested in selling my parents the home that they had selected. Even though they were prequalified, the realtor essentially told my dad, “You and your family would likely be happier in another neighborhood because the families that live in this neighborhood are professionals.” The other neighborhood that the realtor recommended was a low-income subsided housing area; a place that the realtor likely felt was a more appropriate place, as my father was a foreman for an automobile company.

These schooling and home-purchasing practices exemplify dejure and defacto segregation (

Acuña 2015;

Donato and Hanson 2012) and were used as mechanisms to perpetuate positionality and power of the White population. My parents ended up finding a nicer house and neighborhood, and I attended a predominantly White high school. As an adolescent, I noted the differential treatment and lower expectations of Mexican American and African American students at my high school.

Throughout my experiences, my constant anchor was the cultural, historical, and linguistic pride that had been instilled in me by my parents, Mamá Julia, and Tío José María. According to

Yosso (

2005), this anchor is the cultural wealth that Latino families provide their children to support their success. While I had always considered myself a first-generation college student, as I was the first in the immediate family to attain a college degree, and eventually earned a terminal degree, I also recognize that my Tío José María obtained his

licenciatura (bachelor’s degree) as a

normalista (teacher), and later became a school principal. Once I obtained my bachelor’s degree and bilingual education teacher certification, I always knew that I want to go beyond my position as a teacher. While I loved teaching and serving the bilingual community, I also wanted to help my community even more.

I think now that I was heavily influenced by my family, but also Tío José María, because of his commitment to the community and social justice—“Tenemos que ayudar el pueblo” (We have to help the people). I later obtained my master’s degree and became a bilingual school counselor. However, as a counselor, I still felt I needed to do more for my community as I noted that not all teachers were as compassionate or well-prepared to work with diverse student populations. Hence, I pursued my doctoral degree and obtained a faculty position and created a research center to study and prepare culturally and linguistically efficacious teachers.

While I felt I had achieved my education and career goals, I also wanted to share my knowledge through research as well as teaching. I made it my goal to be a top scholar in the field as well as an exemplary educator. To date, I have been recognized as a top scholar in the field, attaining various national awards. However, what is most important to me is ensuring that the teachers who interact with the daily lives of diverse children are well prepared. As an associate dean, I am able to guide our educator preparation program’s vision for the curriculum as well as the field and clinical experiences in which our teacher candidates participate. Have I achieved my professional goals? Well, I can say that our teacher preparation program is being transformed and well under way in preparing all our teacher candidates for the diversity that exists within the US. But there still is much work to be done and these efforts must be sustained over time to ensure social and educational justice.

3. Discussion

As I recount these experiences, I see the interplay and struggles among identities, positionality, and power. The themes highlighted in this manuscript expound on the formation of self within figured worlds that people along borders/spaces occupy through time as both colonizer and colonized, and for some eventually become liberated when they attain

concientización (

Freire 1993) of their cultural-historical self.

Urrieta (

2007a,

2007b) theorizes that the cultural activities in which individuals engage result in identity formation and their positionality within their figured words.

As I reflected on the first theme of Situational Identities, Positionality, and Power, I considered the historical period in which this occurred. During the Middle Ages, status was negotiated based on the circumstance of birth—a child was born into the role of a serf, noble, or clergy. As I considered Catalina’s story, I contemplated about how her identity and positionality were tied to her status. Catalina was the child of an Abad, but her mother is not identified in any historical documents. Priests were allowed to marry, so this leaves me wondering why her mother is never identified; perhaps her mother was noble. Catalina must have been considered of noble status, as the mistress (spouse) of Charles II as she and her children were financially supported and recognized by the court.

While she attained this position and identity, I must ask “Did Catalina have a choice in becoming Charles’ lover? Was she bowing to the expectations foisted onto the women of her time?” Perhaps she thought that becoming his lover would be advantageous and provide her status. Some scholars suggest that women of the court, while considered pious and not equal to men, had power in that they often served as counsel to the noble men (

Erler and Kowaleski 1988;

Narbona-Cárceles 2001;

Stuard 2012).

Further, to preserve the status quo, it was observed that nobles married other noble family members, which often included second cousins. Essentially, status was passed down through the generations, where positionality and power are retained. The awarding of titles, land, and wealth afforded and secured Catalina’s descendants and my antepasados’ identity, positionality, and power as nobles.

As I considered the second theme of Renegotiated Identities, Positionality, and Power, I thought about how generational power and wealth are sustained overtime within figured worlds. I wonder what my antepasados thought about their status or if this crossed their minds, since this was the natural order of life. At the time, people were born with or without privilege and were made to believe that they had to accept that fate in life. Those with privilege had attained their position because they had been blessed by God. I also thought about how my paternal grandmother, Mamá Julia, would speak about choosing the right husband, para lavar la sangre—to wash away any impurities in the blood. Her beliefs about positionality were clearly embedded in her historical memories of her figured world.

As I observed the third theme,

Reconstituted Identities, Positionality, and Power, during this era there was a shift from conqueror to conquered people as a result of conflicts over the rights to claim geographic spaces and dominate other people. The spread of Catholicism was achieved through persecution, strife, and domination. Interestingly, while Spain and Latin America continues to be predominately Catholic, a number of the original conquerors, with last names like Martínez (as well my other surnames—Bustos, Salazar, and Flores, see

Gamero 2020), were likely descendants of Crypto-Jews or new Christians. As part of the Jewish diaspora, families chose to be baptized during the Spanish Inquisition rather than face religious persecution (

Wiznitzer 1962). The Spaniards, whose identity was likely linked to Catholicism, perceived their role to conquer the indigenous population through the conversion to Christianity (

Martínez 2010), while simultaneously claiming lands to increase their position, wealth, and power in the new world.

Similarly, the US Americans saw their role as having the divine right to rule over the Americas, and also to position the US as a powerful nation. My Tío José María’s (

Martínez y Martínez 1978) suggestion that the North American’s “mutilation” of the Mexican northern lands reveals a deep sense of resentment as well as a loss of power and positionality of México and the

Mexicano. As

Freire (

1993) pronounces for those who have been oppressed; “they are at one and the same time themselves and the oppressor whose consciousness they have internalized” (p. 30). In this shift of power, the conqueror of indigenous lands becomes the conquered, and unfortunately, there is no recognition that our

antespasados had engaged in similar intrusive actions, as well as the pillaging of natural resources and destroying the codices that recorded indigenous history.

Yet, as I reflect, why was it that the Spaniards are considered conquerors and that label is not attached to those who were colonizing, invading, and raiding other indigenous lands and natural resources in North America? The answer is simple: it is how history is written by those with power. We know that these notions of power and world domination are nothing new. Throughout history, different groups (Visigoths, Greeks, Romans, etc.) have had this notion that they were destined to rule over the world. It is part of an identity forged within a figured world in which the privileged believe that they are imbued with such positionality that they have an inherent right to dominate others.

Hence, through conflict and force, the conquistadores of the new world were no different than other conquering groups. Also, those once conquered, for example, during the Jewish diaspora, became conquerors in the name of religion or for the sake of the mother country. We see this clash and conflict occurring within our modern day, in which one group attempts to subjugate other groups, through various means, e.g., economic, linguistic, political, or religious oppression. Why humankind is driven to dominate others is clearly a flaw we possess.

In considering the fourth theme,

Repatriated Identities, Positionality, and Power, we begin to see an identify and positionality shift with the transfer of power. Borders were reconfigured during the Texas Revolution. That is, the figured world was transformed in such a way that certain individuals were no longer welcomed or accepted. Mexican Americans often say “We didn’t cross the border; the border crossed us.” This saying clearly reflects that their descendants had ruled the land and further demonstrates the fluidity of the border as an area of conflict. As part of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, Mexicans were classified as White and had full citizenship rights. However, history clearly demonstrates the subjugation of Mexicans and Mexican Americans. Examples include land ownership restrictions, dejure and defacto segregation, and deportation (

Acuña 2015;

Donato and Hanson 2012).

Montejano (

1987) surmises:

... Texas independence and annexation acquire special significance as the events that laid the initial ground for invidious distinction and inequality between Anglos and Mexicans. In the “liberated” and annexed territories, Anglos and Mexican stood as conquerors and conquered, as victors and vanquished, a distinction as fundamental as any sociological sign of privilege and rank.

(p. 5)

Essentially, a displacement of positionality and power occurred. As

Montejano (

1987) posits, it was the transposition of the old order with the new world order; the perpetuation of this new world order was ensured through segregated schooling, the denial of bilingual instruction, and the lack of equal educational opportunities. Eventually, this marginalization was challenged during the civil rights era, which resulted in court case rulings, changes in public policies, and schooling practices, such as The Bilingual Education Act of 1968.

The duality or hybridity of identity that exists along the border (

Anzaldúa 1987,

1997) is evident in these historical and personal accounts. Due to war, families moved to the US, with some of these families remaining in the US, while others returned to México. My Mamá Julia (paternal grandmother) would say “

Gracias a Dios, que Santa Ana nos dejo de este lado” (Thank God, Santa Ana left us on the US side) whenever she would get upset with Mexican political issues or injustices. Nevertheless, she was proud to be a

Mexicana and, as I reflect, I do not recall her ever identifying herself as a Mexican American or Tejana.

These stories illuminate the psychological conflict that Mexican Americans feel, as if they reside in an “in-betweenness” of cultural, geographic, historical, linguistic, psychological, or political spaces. Rather than approaching this in-betweenness from a deficit perspective,

Anzaldúa (

1987) refers to this space as the

nepantla in which border-crossers have the unique capacity to move within and among multiple worlds embracing their multiple identities as opposed to being regulated to a single identity. Likewise,

Urrieta (

2007b) captures this notion that we live in multiple figured worlds in which we forge our identities.

The final theme,

Revitalized Identities, Privilege, and Power, demonstrates that while a country may attempt to conquer a people, the people can resist subjugation and marginalization; further, some become self-determined, empowered, and liberated. As

Anzaldúa and Keating (

2009) proclaimed, “

Caminante, no hay puentes, se hace puentes al andar” (Voyager, there are no bridges, one builds them as one walks; p. 73). So, even when bridges or opportunities are removed, we can also create a path for ourselves and others.

Yosso’s (

2005) work also bears relevance here. As opposed to cultural capital, cultural wealth is perpetual. Such cultural wealth reflects the knowledge and ways of being that family’s nurture: “aspirational, navigational, social, linguistic, familial, and resistant capital” (p. 69). These various forms of cultural wealth were evident in my experiences. I was encouraged to be bicultural-bilingual, encouraged to strive toward greater achievement, and provided with a variety of experiences to help me navigate the world. The stories of my family’s struggles taught me to resist others’ attempts to subjugate me and served me to feel self-empowered.

Essentially, the struggle of borders created through conquests simply reflect lines drawn by cartographers. In speaking about

la lucha de fronteras (border struggles),

Anzaldúa (

1997) posits that because Mexican Americans exist and have lived in the

nepantla, we are able to traverse in and out from one culture to another. We represent the intersectionalities of cultures and the uniqueness of each culture. This is our strength as a people.

5. Conclusions

Who am I? is an esoteric question that my colleague and I have encouraged educators to contemplate (

Clark and Flores 2001;

Flores and Clark 2017). I also assign an

autohistoria activity to my class, in which my students reflect on their families’ origins and situate these within historical events. This activity is always eye-opening for my students, as they consider that the Americas did not begin with the landing of the Pilgrims on Plymouth Rock. Moreover, for those of Spanish or Latino descent, they come to realize that their identities, positionality, and power are a fusion of the various spaces as figured worlds that their

antepasados have occupied and they are occupying, as well as the intermixing of various ethnic and religious groups. For some, this is a cathartic experience in which they embrace their indigenous self while gaining “voice and power to name one’s identity and define one’s reality” (

Comas-Díaz 2001, p. 116). Essentially, as

Flores and Clark (

2017) stipulate,

se despierta el ser in which the self is awakened and transformed; this liberation fuels the sense of self and concientización.

In this

autohistoria, I delved even deeper as much as possible to find my paternal family origins. This exploration of my historical-self in the borderlands (

Anzaldúa 1987,

1997) broadened and deepened my own identity and

concientización (critical consciousness). Who am I? As I considered this question, I recalled my mother telling me that when I was born, while I had almost no hair as a young child, my hair had a reddish hint and people would question her as to whose baby I was. After all, both my parents had dark hair. The answer may lie in the past. I found an unverified museum portrait of Catalina as a beautiful red-haired, fair-skinned woman posted on ancestry and it reminded me of Mamá Julia’s fair skin and light brown hair with a reddish hint. We inherit our genetic traits from our parents, who have inherited their genetic traits from their

antepasados. However, I am Catalina, my various

antepasados, my Mamá Julia, and my parents beyond genetic traits; my historical self and memory as a figured world are embedded in their experiences.

As is observed in this

autohistoria, my

antepasados did possess tenacity; they were adventurers and risk-takers in uncharted spaces. Throughout time, they traversed and occupied various educational, geographic, historical, linguistic, and social spaces. As I explored these figured worlds within the borderlands as part of my

autohistoria, I found historical accounts of oppression and liberation. As nobles and colonizers, my

antepasadsos used their positionality and power to advance themselves and their families. My

antepasadsos negotiated their places in the world to maintain and sustain their status. As colonizers, they claimed land that was indigenous for themselves and for their mother country. While I can certainly empathize with this loss of my ancestors at the hands of the indigenous population, I also believe that these were indigenous lands, and that our ancestors were occupying and encroaching upon the indigenous populations. Indigenous tribes saw my

antepasados as threats to their way of life and, as such, fought for their positionality and status. While I cannot judge the past decisions based on our present ways of thinking, retrospectively I am conflicted. As

Urrieta (

2007a) notes, within figured worlds we will encounter oppressive experience which we may choose to accept, reject, or negotiate. In negotiating this conflict, I can understand that my

antepasados were trying to secure a better life for themselves and their families. This goal is one that resonates with many of us; nevertheless, one we should reflect upon to ensure that our actions do not lead to the marginalization or subjugation of others, rather we should promote the self-determination and liberation of others.

Nevertheless, it is also evident that through self-anointed decrees of manifest destiny or under the guise of religious pronouncements, the land of my ancestors, as well as other conquerors, was colonized in the name of the madre patria (mother country), and eventually was claimed by another powerful colonizer. Thus, despite of generational positionality and power, other political factors ultimately diminished these claims.

Throughout our history, there has been a constant struggle for land ownership, and it is intimately tied to domination. As human beings, we have failed to learn that world domination is impossible, because in time people become resistant to such proclamations and liberate themselves, as is reflected in my autohistoria. Traversing through time and space as a figured world raised my concientización of who I am as cultural historical being, but also left me wondering about my other historical roots.