Patriarchs, Pipers and Presidents: Gaelic Immigrant Funerary Customs and Music in North America

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Discussion of Evidence and Analysis of Sources

The Celts… were so partial to music, thought it indispensable on occasion of death. The bards always attended at the raising of the tomb, besides singing the praises of the dead in the circles, and the poem or rather both it and the music, was called the coronach [Corronach].(ibid., p. 487)

On the occasion of a death in a Gaelic household, it was the custom up to about a hundred to a hundred and fifty years ago (and in isolated cases, much more recently), to sing the virtues and mourn the loss of the person who had died, to a special kind of music. This was usually sung by a professional mourning woman, the bean-tuiream (plural, Mnathan-tuirim). It was a ritual which was looked upon as the proper right and need of everyone, high or low, to ensure their happy passage to the next world, the bàs-sona, or ‘happy death’.

At funeral processions, which had been, and still are conducted with remarkable regularity, the pipes, in strains of pathos and melody, followed the bier, playing slow plaintive dirges, composed for and used only on such occasions. On arriving near the church-yard, the music ceased, and the procession formed a line on each side, between which the corpse was carried to its narrow abode.

Unfortunately, there is no mention of the pipe music performed on that day.Died, February 22d, at his residence, at East Point, justly regretted, MR DONALD BEATON, sen., at the patriarchal age of 95 years. He was born 20 July 1746, in the Village of Achlauchrach, in the Parish of Cappach, Lockaber, and emigrated to this Island shortly after its conquest by the British, and was one of its first settlers. By untiring industry, he brought up a large and respectable family; and had the happiness, before his decease, to behold his progeny increase to the third and fourth generation. His remains were conveyed from his late residence to the Cemetery of St Columbus, followed by a numerous and respected assemblage of relatives and friends; and, according to his strict injunctions to his surviving friends, his funeral was attended to the grave by the National airs of his native glens! The solemn Piobrachd as it died away in the distance, reminded us of the “deeds of the times of old”, when the Chieftain’s corpse was followed by the weeping clan, and the mournful Coronach [sic] of the Highland pipes reverberated from the neighbouring hills! REQUIESCATA IN PACE!

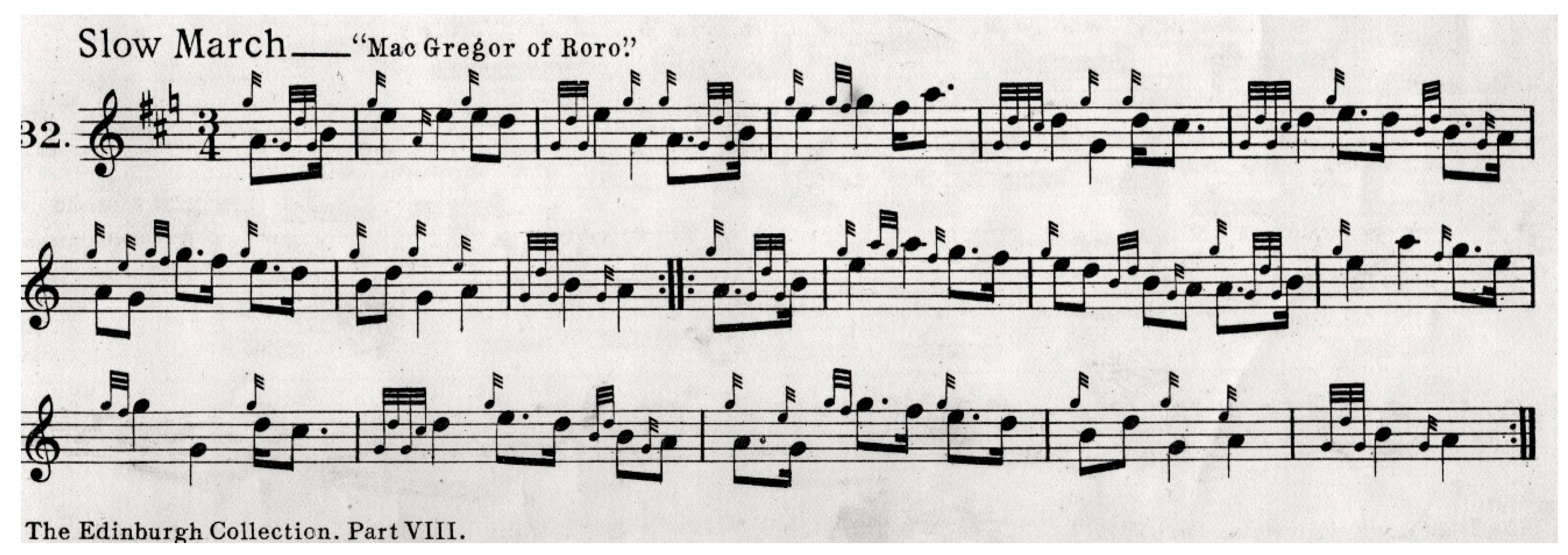

A thorough believer in everything Highland, his dearest delight, second only to matters of religion, was to hear and talk of the clans and their deeds in “auld lang syne.” He had himself all the virtues characteristic of them; a great contempt of falsehood and meanness. Rugged honesty and sterling integrity marked him. It need not, therefore, surprise anyone that his friends—and above all his own sons—should have carried out his funeral in harmony with his own old-time notions, in a word that his should be in the time-honored Highland style which honored the worthy departed by the pibroch and bearing the remains on the shoulders. Thus, then, were the deceased’s remains tenderly and respectfully borne to their last resting place by the men of Mabou-some, indeed, of whom, it was noted had already passed their three score and ten. Yes, slowly, orderly, and solemnly one of the largest funeral corteges for many years seen in Mabou thus wended its way, timed to the wail of McCrimmons’ [sic] lament, Lochaber, Flowers of the Forest, McGregor’s, and Mac ic Raonial na Caepeach. After a Requiem High Mass by Rev. John McMaster, P.P., all that was mortal of good old Aonas Og was buried with the blessing of the Church whose Sacraments had prepared him to meet his Lord and his God. May his soul rest in peace!

[t]he tune goes back at least as far as the early 17th C as it occurs in the Skene Mandora MS dated to circa 1615–1625, so feasibly could extend back to the event itself in 1513. It also features, not as a lament but as a reel in the Gillespie MS, (1768) and with added variations in Oswald’s Caledonian Pocket Companion.(ibid.)

Tha mulad, tha mulad, Tha mulad gam lìonadh

(Sorrow is, sorrow is, sorrow is filling me)7

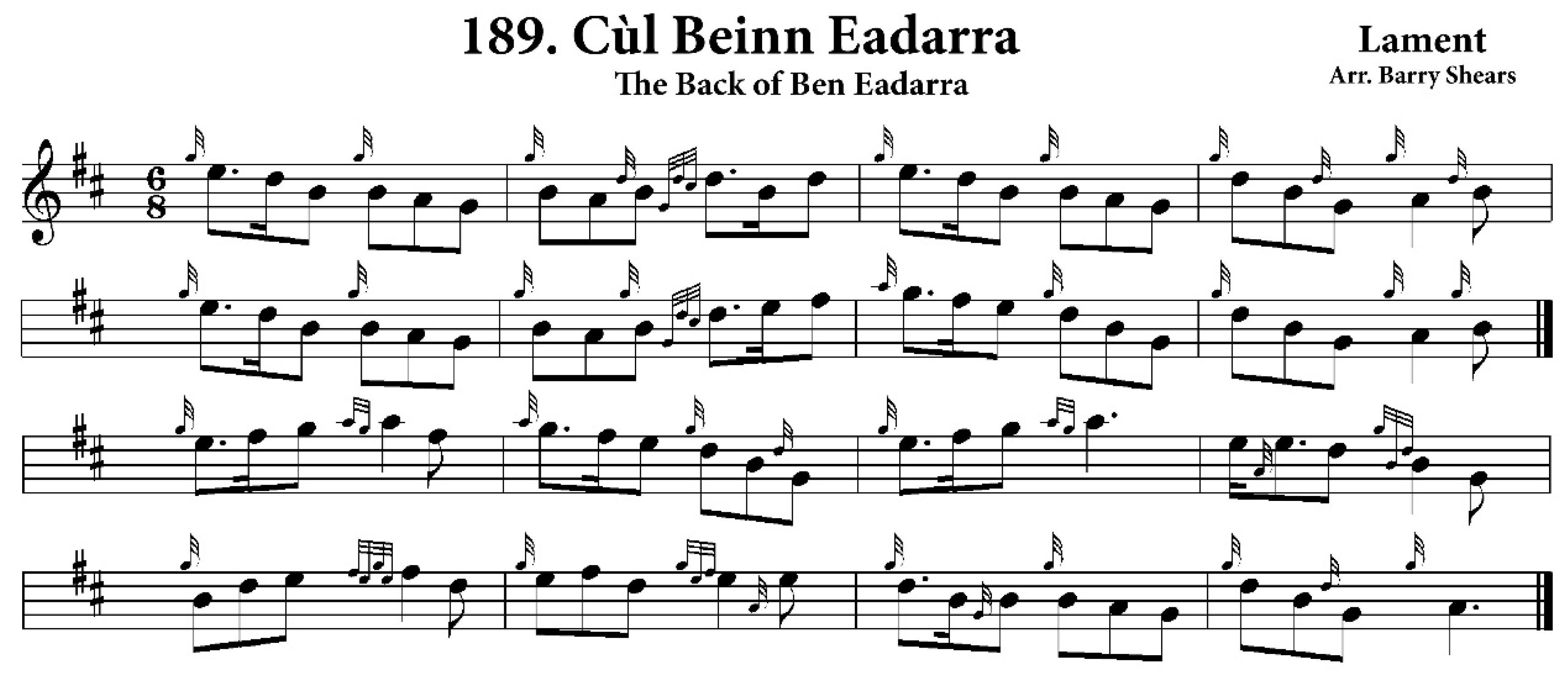

His family wanted an old-style Scotch funeral with six men actually carrying the corpse behind a piper. In spite of knowing of Ranald’s aversion to [the man], they still approached him to lead the cortege and were very surprised when they found that he was willing to play for his old adversary. On the way to the graveyard Ranald played the evocative slow air “Fuadach nan Gaidheal”.(The Exile of the Highlanders/Lord Lovat’s Lament)

All went well and, after the funeral, someone asked Ranald what was the beautiful lively tune that he had played on the way back from the graveyard. Ranald replied in Gaelic that it was “Cuir do Shròin an Tòin a’ Choin Dubh”.(Put Your Nose in the Black Dog’s Arse) (Gillis 2008)

Angus MacMillan Fraser, widely known bagpiper, who died on Sunday at the age of 64, was buried yesterday in Mount Olivet Cemetery in Maspeth, as his band of pipers played the Children’s Lament. More than 400 were present at the burial, including representatives of the Clans MacDonald, Chisholm and MacKenzie. Services at the grave were conducted by Fred Taggart, past chieftain of the Caledonian Club, of which Mr. Fraser was first chieftain. The pipers, known as Angus Fraser’s Lovat Pipe Band, which consisted of twenty-five pieces, played four numbers during the services.

4. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References and Notes

- Blankenhorn, Virginia. 1978. Traditional and Bogus Elements in ‘MacCrimmon’s Lament’. Scottish Studies 22: 45–67. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Grace. 1964. Highland Heritage. London: Collins. [Google Scholar]

- Cannon, Roderick. 1995. The Highland Bagpipe and Its Music. Edinburgh: John Donald Publishers Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Chartsfo. 2007. Gerald Ford Memorial-Bagpiper. Available online: https://youtu.be/2npzAKnI2bQ (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Collinson, Francis. 1966. The Traditional and National Music of Scotland. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. [Google Scholar]

- Colonial Herald and Prince Edward Island Advertiser. 1841. April 24, pp. 2–3. Available online: https://islandnewspapers.ca/islandora/object/newspapers:84/newspaper_about (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Creighton, Helen, and Calum MacLeod, eds. 1964. Gaelic Songs in Nova Scotia. Ottawa: National Museums of Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Dickson, Joshua. 2006. When Piping Was Strong. Edinburgh: John Donald Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, William. 2000. The Highland Pipe and Scottish Society, 1750–1950. Edinburgh: Tuckwell Press. [Google Scholar]

- Flood, William Gratton. 1911. The Story of the Bagpipe. London: Walter Scott, New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, John G. 1998. Traditional Gaelic Piping, 1745–1945. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, John G. 2002. Old and New World Highland Bagpiping. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gillis, Allan J. 2008. May 18. Personal communication with author.

- Harper, Marjory. 1998. Emigration from Scotland between the Wars. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Logan, James. 1847. The Scottish Gaël; or, Celtic Manners, as Preserved among the Highlanders, 5th ed. Hartford: S. Andrus and Son, vol. 2. First published 1831. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald, Allan. 1995. The Relationship between Pibroch and Gaelic Songs: Its Implications on the Performance Style of the Pibroch Ùrlar. Unpublished. MLitt Thesis, Edinburgh University, Edinburgh, UK. Available online: https://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/~rja14/musicfiles/manuscripts/allanmacdonald/ (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- MacDonald, James M. 1968. Piping in Cape Breton. Piping Times, 22, 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- MacDougall, Hector, ed. 2004. Smeorach nan Cnoc‘s nan Gleann, The Songster of the Hills and Glens. North Sydney: Northside Printers Ltd. First published 1939. [Google Scholar]

- MacKay, Angus. 1838. A Collection of Ancient Piobaireachd or Highland Pipe Music. Aberdeen, Inverness and Elgin: Logan & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie, John, and James Logan. 1841. Sar-Obair nam bard Gaelach: Or the Beauties of Gaelic Poetry, and the Lives of the Highland Bards. Glasgow: MacGregor, Polson and Co. [Google Scholar]

- MacLean, Vincent W. 2014. These Were My People, Washabuck: An Anecdotal History. Sydney: Cape Breton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- MacNeil, Joe Neil. 1987. Tales until Dawn: The World of a Cape Breton Gaelic Story-Teller. Translated and Edited by Shaw John. Kingston and Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press. [Google Scholar]

- MacNeil, Neil. 1971. The Highland Heart in Nova Scotia. Toronto: S. J. Reginald Saunders. First published 1948. [Google Scholar]

- McDonell, Angela. 2019. December 27. Personal communication with author.

- McEwan-Fujita, Emily. 2020. January 21. Personal communication with author.

- McIan, Robert Ronald, and James Logan. 1845. The Clans of the Scottish Highlands. London: Ackermann and Co., Strand, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- McRae, Finlay. 1845. Parish of North Uist. In The New Statistical Account of Scotland 1834–45. Edinburgh: William Blackwood & Sons, vol. 14, pp. 159–181. First published 1837. [Google Scholar]

- New York Herald Tribune. 1938. March 9, npa.

- New York Times. 1938. March 12, p. 17.

- Rankin, Effie. 2019. December 17. Personal communication with author.

- Sanger, Keith. 2019. Laments at Funerals. Bob Dunsire Bagpipe Forums. Available online: Bob.dunsireforums.com (accessed on 12 December 2019).

- Seanair. 1994. Gaelic Names of Pipe Tunes. Kingston: Iolair Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Shears, Barry. 1991. The Gathering of the Clans Collection. Halifax: Privately Printed. [Google Scholar]

- Shears, Barry. 2008. Dance to the Piper: The Highland Bagpipe in Nova Scotia. Sydney: Cape Breton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shears, Barry. 2018. Play It Like You Sing It: The Shears Collection of Bagpipe Culture and Dance Music from Nova Scotia. Halifax: Bradan Press, vol. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Tennyson, Brian Douglas. 2007. Percy Wilmot, a Cape Bretoner at War. Sydney: Cape Breton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- The Black Watch. 1966. War Pipe and Plaid (with liner notes). London: International SW99407. [Google Scholar]

- The Casket. 1899. June 15, p. 5.

- The Havengore Trust. 2013. Footage of Sir Winston Churchill’s Funeral. Available online: https://youtu.be/vjtpwPRynqE (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- The Piobaireachd Society, ed. 1925–2015. Piobaireachd with a Preface and Explanatory Notes, Books 1–16. Edinburgh: The Piobaireachd Society. [Google Scholar]

- Wake and District. 2009. Ronald Reagan Funeral-Amazing Grace. Available online: https://youtu.be/Wo7MexlaQ30 (accessed on 13 May 2020).

| 1 | This informal survey was conducted recently on the Dunsire Forums, a chat group for pipers around the world. The half a dozen or so pipers from North America, who responded to my question about piping at funerals, suggested that pipers were featured more frequently at male than female funerals. The split was roughly 75 to 25, showing a decided male bias towards this tradition. My correspondents were at a loss to explain why this was the case. |

| 2 | Videos of all three funerals can be found on YouTube, as well the funeral service for Sir Winston Churchill (The Havengore Trust 2013), where bagpipes were also played. |

| 3 | It should be noted that I have observed some aspects of Logan’s description of piping in the early 19th century still being practiced among the ear-trained pipers in Cape Breton and Newfoundland until the late 20th century. |

| 4 | For further discussion on the subject of pibroch song, see Allan MacDonald’s unpublished MLitt thesis, “The Relationship between Pibroch and Gaelic Songs: Its Implications on the Performance Style of the Pibroch Ùrlar”, Edinburgh University, 1995. https://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/~rja14/musicfiles/manuscripts/allanmacdonald/. |

| 5 | This information was kindly sent to me by Angela McDonell, Wellington, Prince Edward Island. |

| 6 | This newspaper reference was kindly sent to me by Effie Rankin, Mabou, Cape Breton. |

| 7 | Translation modified by Emily McEwan-Fujita, personal communication with author, 21 January 2020. |

| 8 | This album also featured a musical tribute to John F. Kennedy that included “The Mist Covered Mountains” and a new composition, a hornpipe named for the late President and composed by Canadian piper, Bill Gilmour. |

| 9 | Pipers have continued to create new music to express loss. Two laments with a Nova Scotian connection were composed in North America in the 20th century by two pipers who had served during the First World War. These were “Courcellette” and “Captain Angus L. MacDonald”. The first was a lament composed by Pipe Major Jock Carson to commemorate the 25th Battalion’s losses during the Battle of Courcellette, 15 September 1916 (Tennyson 2007, p. 210), and the second was composed by Pipe Major Fraser Holmes, New Glasgow, Nova Scotia, entitled “Captain Angus L. MacDonald, Lament for a Friend” (Shears 1991, vol. 1, p. 75). Angus L. was the last Gaelic-speaking Premier of Nova Scotia, and both he and Holmes served in the 85th Battalion, Nova Scotia Highlanders, during the First World War. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shears, B. Patriarchs, Pipers and Presidents: Gaelic Immigrant Funerary Customs and Music in North America. Genealogy 2020, 4, 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy4020063

Shears B. Patriarchs, Pipers and Presidents: Gaelic Immigrant Funerary Customs and Music in North America. Genealogy. 2020; 4(2):63. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy4020063

Chicago/Turabian StyleShears, Barry. 2020. "Patriarchs, Pipers and Presidents: Gaelic Immigrant Funerary Customs and Music in North America" Genealogy 4, no. 2: 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy4020063

APA StyleShears, B. (2020). Patriarchs, Pipers and Presidents: Gaelic Immigrant Funerary Customs and Music in North America. Genealogy, 4(2), 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy4020063