A Little Bit of That from One of Your Grandparents: Interpreting Others’ Direct-to-Consumer Genetic Ancestry Results

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Interpreting Direct-to-Consumer Genetic Tests

2.2. How Genetic Tests and Results Work

2.3. Genetic Ancestry Research

2.4. Bottom-Up and Top-Down Processing of Genetic Ancestry Results

2.5. Research Questions

- RQ 1:

- How do individuals interpret genetic ancestry results?

- RQ 2:

- How does understanding a genetic test’s scientific explanation shape result interpretations?

- RQ 3:

- How do individuals determine whether genetic ancestry results support identity claims?

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

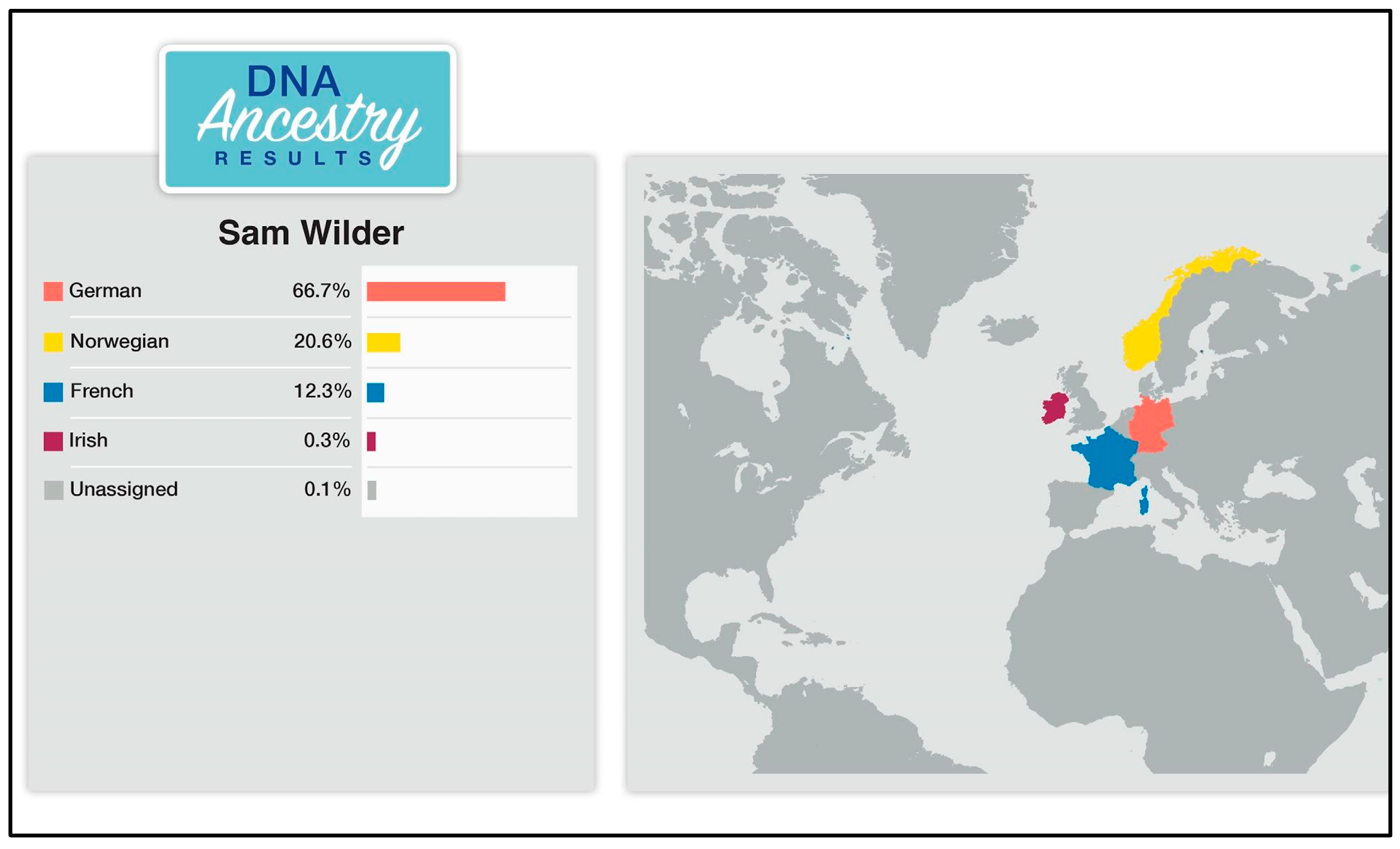

3.2. Stimulus Materials

3.3. Questionnaire

3.4. Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Superficial Interpretations

4.1.1. Formatting Simplicity

I think [interpreting the results] was pretty simple, especially with the map right there. Like, even if you didn’t know where these countries were originally on the map, it is right there, and so you can just look at the map and it will tell you. And plus, it’s color coded, so that really helps a lot, too.(Stephanie)

4.1.2. Content Simplicity

I think that these results are pretty plain … If it had been, like, Western European and, like, Northern African, I’d have been, like, “Oh, that’s interesting.” But this is all, like, the same general region.(Laura)

4.1.3. Unclear Meaning

Another participant, asked what it meant to be “66.7% English and Welsh,” followed similar reasoning:That’s the part I’m confused about. I don’t know what that means. … I don’t know, it’s hard to trace that. Like, are 20.6% of his ancestors were Norwegian? Or is he alone 20.6%?(Ashley)

If it’s, like, the amount of family members he’s had? … I’d think that it’s just out of all of his ancestors, 66.7, maybe, that percent of his past family, maybe, was born in that country.(Nicole)

Thinking about Germany and Norway being so close in this map, maybe those ancestors traveled from one place to the other, maybe because at the time it was easier, maybe … when all the situations in World War II were happening, that was when they traveled to Norway or vice versa.(Katherine)

4.2. Scientific Explanation Confuses and Frustrates

4.2.1. Comprehension Difficulties

If I was understanding it right, they were saying that 50% of your DNA matches other people … I got, like, how they calculated it, because it says they determine it by, like … they track it by basically spanning across the globe, and tracking your DNA, and going across the globe. But I didn’t get, like, how they get your DNA, which is kind of what I was looking for, and that’s what got kind of confusing for me.(Stephanie)

4.2.2. Doubting the Results

I feel like if you buy a toaster and 50% [of the time] it would work and 50% it won’t, it’s, like, why would I buy that toaster? It’s not worth it if it’s only going to make toasts every other day. That’s just not a reliable company to me.(Laura)

4.3. Legitimate Ancestry Identities

4.3.1. Personal Choice and Culture

It is not my place to decide who someone believes they are, or what culture they want to believe in, or celebrate, or put forth their love for. Because I feel like if you appreciate it, then it’s fine to identify with it to a certain extent.(Christina)

I guess DNA can tell you maybe where your ancestry was located but if you’ve never learned what that means, or what that history is, or the traditions that are in that culture, and you don’t really practice that, then that’s not really who you are.(Andrea)

4.3.2. Thresholds

I feel like, if someone were to tell me that “I am French,” and I say, “What percentage of French are you?” and they say a number under, like, 20%, I would say, “Oh. You are not really French.” I feel like anything under 10% might be stretching it. You are not really that.(Andrea)

I feel like it is mainly based on what the person wants to interpret their result as. But if we are going to go numerical, I’d say at least 10% of something in order to say, “Yes, I am definitely this.”(Christina)

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Interview Question Protocol

- How difficult or easy was it to interpret these results?

- Have you taken a test like this before?

- What did you learn from your results?

- What do your test results mean to you?

- What does the right section of the results tell us? What does the left section tell us?

- Depending on the answer, ask a follow-up to get closer to what the numbers really mean. Ex. What does it mean to be 4% Welsh?

- Thinking specifically about the list of countries (or regions), how difficult or easy was it to interpret these results?

- What do these results say about this person’s ancestry? (Probe as necessary)

- What continents are most of this person’s ancestors from?

- What continents are the ancestors not from?

- Were you surprised by these results? Why or why not?

- So, if this person came to you and said, “You know what, I’m ________.” And then they gave you these results, would you think that’s an accurate representation of their identity? (fill in the blank with points below)

- Ask about the largest and the smallest percentages (excluding unassigned)

- One country between 4%–5% (excluding unassigned)

- For the stimuli with only 4 countries just ask about the largest and smallest percentage (excluding unassigned)

- At what point or what percentage would you consider this person to be_________? (the lowest % on the stimulus)

- What does the unassigned ancestry label mean?

- Do you trust these results? Why or why not?

- 12.

- What do these instructions mean?

- 13.

- Would you consider purchasing an ancestry DNA test? Why or why not?

References

- 23andMe. 2019. Ancestry Composition: 23andMe’s State-of-the-Art Geographic Ancestry Analysis. Available online: https://www.23andme.com/ancestry-composition-guide/ (accessed on 15 December 2019).

- Aertsens, Joris, Koen Mondelaers, Wim Verbeke, Jeroen Buysse, and Guido Van Huylenbroeck. 2011. The influence of subjective and objective knowledge on attitude, motivations and consumption of organic food. British Food Journal 113: 1353–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agurs-Collins, Tanya, Rebecca Ferrer, Allison Ottenbacher, Erika A. Waters, Mary E. O’Connell, and Jada G. Hamilton. 2015. Public awareness of direct-to-consumer genetic tests: Findings from the 2013 US Health Information National Trends Survey. Journal of Cancer Education 30: 799–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolnick, Deborah A., Duana Fullwiley, Troy Duster, Richard S. Cooper, Joan H. Fujimura, Jonathan Kahn, Jay S. Kaufman, Jonathan Marks, Ann Morning, Alondra Nelson, and et al. 2007. The science and business of genetic ancestry testing. Science 318: 399–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borry, Pascal, Mahsa Shabani, and Heidi C. Howard. 2013. Nonpropositional content in direct-to-consumer genetic testing advertisements. The American Journal of Bioethics 13: 14–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2012. Thematic analysis. In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology. Edited by Harris Cooper. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, vol. 2, pp. 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Brodwin, Paul. 2002. Genetics, identity, and the anthropology of essentialism. Anthropological Quarterly 75: 323–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brubaker, Rogers. 2016. The Dolezal affair: Race, gender, and the micropolitics of identity. Ethnic and Racial Studies 39: 414–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucher, Hans-Jürgen, and Peter Schumacher. 2006. The relevance of attention for selecting news content: An eye-tracking study on attention patterns in the reception of print and online media. Communications 31: 347–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casali, John G., and Kenneth B. Gaylin. 1988. Selected graph design variables in four interpretation tasks: A microcomputer-based pilot study. Behaviour & Information Technology 7: 31–49. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, Kurt D., Toby E. Jayaratne, Scott Roberts, Sharron L. R. Kardia, and Elizabeth M. Petty. 2010. Understandings of basic genetics in the United States: Results from a national survey of black and white men and women. Public Health Genomics 13: 467–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council on Foreign Relations and National Geographic. 2016. What College-Aged Students Know about the World: A Survey on Global Literacy. New York: Council on Foreign Relations, September, Available online: https://www.cfr.org/content/newsletter/files/CFR_NatGeo_ASurveyonGlobalLiteracy.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2019).

- Cross, John A. 1987. Factors associated with students’ place location knowledge. Journal of Geography 86: 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs, Julie S., Wändi Bruine de Bruin, and Baruch Fischhoff. 2008. Parents’ vaccination comprehension and decisions. Vaccine 26: 1595–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunlop, Charles E. M., and James H. Fetzer. 1993. Glossary of Cognitive Science. New York: Paragon House. [Google Scholar]

- Felzmann, Heike. 2015. ‘Just a bit of fun’: How recreational is direct-to-consumer genetic testing? The New Bioethics 21: 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foeman, Anita, Bessie Lee Lawton, and Randall Rieger. 2015. Questioning race: Ancestry DNA and dialog on race. Communication Monographs 82: 271–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabel, Jessica D. 2012. Redeeming the genetic Groupon: Efficacy, ethics, and exploitation in marketing DNA to the masses. Mississippi Law Journal 81: 363–438. [Google Scholar]

- Glenberg, Arthur M., Alex Cherry Wilkinson, and William Epstein. 1982. The illusion of knowing: Failure in the self-assessment of comprehension. Memory & Cognition 10: 597–602. [Google Scholar]

- Graf, Nikki. 2019. Mail-in DNA Test Results Bring Surprises about Family History for Many Users. Pew Research Center. August 6. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/08/06/mail-in-dna-test-results-bring-surprises-about-family-history-for-many-users/ (accessed on 7 February 2020).

- Haga, Susanne B., William T. Barry, Rachel Mills, Geoffrey S. Ginsburg, Laura Svetkey, Jennifer Sullivan, and Huntington F. Willard. 2013. Public knowledge of and attitudes toward genetics and genetic testing. Genetic Testing and Molecular Biomarkers 17: 327–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, Adam L., Aliya Saperstein, Jasmine Little, Martin Maiers, and Jill A. Hollenbach. 2019. Consumer (dis-)interest in genetic ancestry testing: The roles of race, immigration, and ancestral certainty. New Genetics and Society 38: 165–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobling, Mark A., Rita Rasteiro, and Jon H. Wetton. 2016. In the blood: The myth and reality of genetic markers of identity. Ethnic and Racial Studies 39: 142–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juengst, Eric T. 2004a. DNA identification. In Encyclopedia of Bioethics, 3rd ed. Edited by Stephen G. Post. New York: Macmillan Reference, pp. 677–83. [Google Scholar]

- Juengst, Eric T. 2004b. Genetic testing and screening: Population screening. In Encyclopedia of Bioethics, 3rd ed. Edited by Stephen G. Post. New York: Macmillan Reference, pp. 1007–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kruikemeier, Sanne, Sophie Lecheler, and Ming M. Boyer. 2018. Learning from news on different media platforms: An eye-tracking experiment. Political Communication 35: 75–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanie, Angela D., Toby Epstein Jayaratne, Jane P. Sheldon, Sharon L. R. Kardia, Elizabeth S. Anderson, Merle Feldbaum, and Elizabeth M. Petty. 2004. Exploring the public understanding of basic genetic concepts. Journal of Genetic Counseling 13: 305–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Sandra Soo-Jin. 2013. Race, risk, and recreation in personal genomics: The limits of play. Medical Anthropology Quarterly 27: 550–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewandowsky, Stephan, and John T. Behrens. 1999. Statistical graphs and maps. In Handbook of Applied Cognition. Edited by Francis T. Durso, Raymond S. Nickerson, Roger W. Schvaneveldt, Susan T. Dumais, D. Stephen Lindsay and Michelene T. H. Chi. New York: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 514–49. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Norman P., Debbie Treise, Stephen I. Hsu, William L. Allen, and Hannah Kang. 2011. DTC genetic testing companies fail transparency prescriptions. New Genetics and Society 30: 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linskey, Annie. 2018. Elizabeth Warren Releases Results of DNA Test. Boston Globe. October 15. Available online: https://www.bostonglobe.com/news/politics/2018/10/15/warren-addresses-native-american-issue/YEUaGzsefB0gPBe2AbmSVO/story.html (accessed on 7 February 2020).

- Lorenzoni, Irene, and Nick F. Pidgeon. 2006. Public views on climate change: European and USA perspectives. Climatic Change 77: 73–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, Amy D. 2019. A white woman searches for her black family: A home DNA test led Christine Jacobsen to grapple with complicated questions about her racial identity. The Wall Street Journal. November 21. Available online: https://www.wsj.com/articles/a-white-woman-searches-for-her-black-family-1157262511 (accessed on 7 February 2020).

- Meyer, Joachim, David Shinar, and David Leiser. 1997. Multiple factors that determine the performance with tables and graphs. Human Factors 39: 268–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Jon D. 2004. Public understanding of, and attitudes toward, scientific research: What we know and what we need to know. Public Understanding of Science 13: 273–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molster, Charles T., Amanda Samanek, and Peter O’Leary. 2009. Australian study on public knowledge of human genetics and health. Public Health Genomics 12: 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Science Board (NSB). 2018. Chapter 7: Science and Technology—Public Attitudes and Public Understanding. Science and Engineering Indicators. Available online: https://www.nsf.gov/statistics/2018/nsb20181/report/sections/science-and-technology-public-attitudes-and-understanding/public-knowledge-about-s-t (accessed on 10 February 2020).

- Nelson, Alondra, and Jeong Won Hwang. 2013. Roots and revelation: Genetic ancestry testing and the youtube generation. In Race after the Internet. New York: Routledge, pp. 277–96. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, Alondra. 2008. Bio science: Genetic genealogy testing and the pursuit of African ancestry. Social Studies of Science 38: 759–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, Eryn J., Madeline C. Jalbert, Norbert Schwarz, and Deva P. Ly. 2020. Truthiness, the illusory truth effect, and the role of need for cognition. Consciousness and Cognition 78: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordgren, Anders, and Eric T. Juengst. 2009. Can genomics tell me who I am? Essentialistic rhetoric in direct-to-consumer DNA testing. New Genetics and Society 28: 157–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, Donald A., and David E. Rumelhart. 1975. Explorations in Cognition. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman and Company. [Google Scholar]

- O’reilly, Michelle, and Nicola Parker. 2013. ‘Unsatisfactory Saturation’: A critical exploration of the notion of saturated sample sizes in qualitative research. Qualitative Research 13: 190–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostergren, Jenny E., Michele C. Gornick, Deanna Alexis Carere, Sarah S. Kalia, Wendy R. Uhlmann, Mack T. Ruffin, Joanna L. Mountain, Robert C. Green, J. Scott Roberts, and PGen Study Group. 2015. How well do customers of direct-to-consumer personal genomic testing services comprehend genetic test results? Findings from the impact of personal genomics study. Public Health Genomics 18: 216–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panofsky, Aaron, and Joan Donovan. 2019. Genetic ancestry testing among white nationalists: From identity repair to citizen science. Social Studies of Science 49: 653–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Cheong-Yi. 2001. News media exposure and self-perceived knowledge: The illusion of knowing. International Journal of Public Opinion Research 13: 419–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, Yvette E., and Yuping Liu-Thompkins. 2012. Consuming direct-to-consumer genetic tests: The role of genetic literacy and knowledge calibration. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 31: 42–57. [Google Scholar]

- Pieters, Rik, and Michel Wedel. 2007. Goal control of attention to advertising: The Yarbus implication. Journal of Consumer Research 34: 224–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post Editorial Board. 2018. Warren still Has to Answer for Her Ethnic Identity Theft. New York Post. October 16. Available online: https://nypost.com/2018/10/16/warren-still-has-to-answer-for-her-ethnic-identity-theft/ (accessed on 7 February 2020).

- Quaid, Kimberly A. 2004. Genetic testing and screening: Predictive genetic testing. In Encyclopedia of Bioethics, 3rd ed. Edited by Stephen G. Post. New York: Macmillan Reference, pp. 1020–25. [Google Scholar]

- Regalado, Antonio. 2019. More than 26 Million People Have Taken an At-Home Ancestry Test. MIT Technology Review. February 11. Available online: https://www.technologyreview.com/s/612880/more-than-26-million-people-have-taken-an-at-home-ancestry-test/ (accessed on 7 February 2020).

- Roth, Wendy D., and Biorn Ivemark. 2018. Genetic options: The impact of genetic ancestry testing on consumers’ racial and ethnic identities. American Journal of Sociology 124: 150–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royal, Charmaine D., John Novembre, Stephanie M. Fullerton, David B. Goldstein, Jeffrey C. Long, Michael J. Bamshad, and Andrew G. Clark. 2010. Inferring genetic ancestry: Opportunities, challenges, and implications. The American Journal of Human Genetics 86: 661–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, Herbert J., and Irene S. Rubin. 2012. Qualitative Interviewing: The Art of Hearing Data, 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford, Adam. 2018. A Brief History of Everyone Who Ever Lived: The Human Story Retold Through our Genes. New York: The Experiment. [Google Scholar]

- Ryffel, Fabian A., and Werner Wirth. 2020. How perceived processing fluency influences the illusion of knowing in learning from TV reports. Journal of Media Psychology 32: 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleckser, Kathryn. 2013. Physician participation in direct-to-consumer genetic testing: Pragmatism or paternalism. Harvard Journal of Law & Technology 26: 695–730. [Google Scholar]

- Scodari, Christine. 2017. When markers meet marketing: Ethnicity, race, hybridity, and kinship in genetic genealogy television advertising. Genealogy 1: 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scully, Marc, Steven D. Brown, and Turi King. 2016. Becoming a Viking: DNA testing, genetic ancestry and placeholder identity. Ethnic and Racial Studies 39: 162–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, Jatin Y., Amruta Phadtare, Dimple Rajgor, Meenakshi Vaghasia, Shreyasee Pradhan, Hilary Zelko, and Ricardo Pietrobon. 2010. What leads Indians to participate in clinical trials? A meta-analysis of qualitative studies. PLoS ONE 5: e10730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, Priti, and Eric G. Freedman. 2011. Bar and line graph comprehension: An interaction of top-down and bottom-up processes. Topics in Cognitive Science 3: 560–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, Priti, Eric G. Freedman, and Ioanna Vekiri. 2005. The comprehension of quantitative information in graphical displays. In The Cambridge Handbook of Visuospatial Thinking. Edited by Priti Shah and Akira Miyake. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 426–76. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, Priti, Richard E. Mayer, and Mary Hegarty. 1999. Graphs as aids to knowledge construction: Signaling techniques for guiding the process of graph comprehension. Journal of Educational Psychology 91: 690–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, Wade. 2019. WWE’s Seth Rollins Discovers He Has Siblings with DNA Test. United Press International. September 11. Available online: https://www.upi.com/Entertainment_News/2019/09/11/WWEs-Seth-Rollins-discovers-he-has-siblings-with-DNA-test/4401568218638/ (accessed on 7 February 2020).

- Shim, Janet K., Sonia Rab Alam, and Bradley E. Aouizerat. 2018. Knowing something versus feeling different: The effects and non-effects of genetic ancestry on racial identity. New Genetics and Society 37: 44–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silk, Kami J., and Roxanne L. Parrott. 2014. Math anxiety and exposure to statistics in messages about genetically modified foods: Effects of numeracy, math self-efficacy, and form of presentation. Journal of Health Communication 19: 838–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, Maria, Laura K. Warren, Ariana L. Harner, and Eugen Owen. 2015. Comparative Indicators of Education in the United States and Other G20 Countries: 2015. In National Center for Education Statistics. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2016/2016100.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2020).

- Vayena, Effy, Christian Ineichen, Elia Stoupka, and Ernst Hafen. 2014. Playing a part in research? University students’ attitudes to direct-to-consumer genomics. Public Health Genomics 17: 158–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, Peter. 2019. Elizabeth Warren Apologized to Cherokee Nation for DNA Test: The Senator Hopes It Will Put This Issue to Bed. Rolling Stone. February 2. Available online: https://www.rollingstone.com/politics/politics-news/warren-dna-test-apology-789180/ (accessed on 7 February 2020).

- Wagner, Jennifer K., and Kenneth M. Weiss. 2012. Attitudes on DNA ancestry tests. Human Genetics 131: 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weise, Elizabeth. 2018. These Are the Top Companies Offering Genealogical DNA Testing to Learn about Your Family. USA Today. December 2. Available online: https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/2018/12/02/genealogical-dna-testing-companies-ancestry-23-andme/2141344002/ (accessed on 20 April 2020).

- Winship, Jodi M. 2004. Geographic Literacy and World Knowledge among Undergraduate College Students. Unpublished Master’s thesis, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA, USA. Available online: https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/bitstream/handle/10919/10177/Final_Thesis_JWinship.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2020).

- Yang, Xiaodong, Liang Chen, and Shirley S. Ho. 2020. Does media exposure relate to the illusion of knowing in the public understanding of climate change? Public Understanding of Science 29: 94–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Li. 2019. Poll: Elizabeth Warren’s Handling of Her DNA Results Hurts Her Favorability—But Not Her Electoral Chances. Vox. May 8. Available online: https://www.vox.com/2019/5/8/18535741/poll-elizabeth-warren-dna-test-2020-democratic-primary (accessed on 7 February 2020).

| Name | Gender | Map Literacy Score (Out of 12) | Experience with Genetic Ancestry Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jessica | F | 11 | Maybe |

| Nicole | F | 9 | No |

| Matthew | M | 10 | Yes |

| Rachel | F | 10 | Yes |

| Allison | F | 12 | Yes |

| Olivia | F | 10 | Yes |

| Emily | F | 6 | No |

| Ashley | F | 7 | No |

| Elizabeth | F | 8 | Yes |

| Jacob | M | 7 | Yes |

| Mary | F | 10 | Yes |

| Brian | M | 7 | Maybe |

| Laura | F | 10 | Yes |

| Christina | F | 10 | Yes |

| Jack | M | 12 | Yes |

| Amy | F | 10 | No |

| Katherine | F | 8 | No |

| Stephanie | F | 5 | Yes |

| Andrea | F | 12 | Yes |

| Andrew | M | 12 | No |

| Total/average | F = 15 M = 5 | 9.3 | Yes = 12 No = 6 Maybe = 2 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bobkowski, P.S.; Watson, J.C.; Aromona, O.O. A Little Bit of That from One of Your Grandparents: Interpreting Others’ Direct-to-Consumer Genetic Ancestry Results. Genealogy 2020, 4, 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy4020054

Bobkowski PS, Watson JC, Aromona OO. A Little Bit of That from One of Your Grandparents: Interpreting Others’ Direct-to-Consumer Genetic Ancestry Results. Genealogy. 2020; 4(2):54. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy4020054

Chicago/Turabian StyleBobkowski, Piotr S., John C. Watson, and Olushola O. Aromona. 2020. "A Little Bit of That from One of Your Grandparents: Interpreting Others’ Direct-to-Consumer Genetic Ancestry Results" Genealogy 4, no. 2: 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy4020054

APA StyleBobkowski, P. S., Watson, J. C., & Aromona, O. O. (2020). A Little Bit of That from One of Your Grandparents: Interpreting Others’ Direct-to-Consumer Genetic Ancestry Results. Genealogy, 4(2), 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy4020054