Abstract

This paper thematizes the topic of the eyewitness report based on Miriam Katin’s transgenerational point of view on the Holocaust, which has a cathartic impact on the author through self-reflexivity. In We Are On Our Own, Miriam Katin draws on her own cultural and transgenerational memory, which is heavily influenced by her mother. The author unveils her parents’ story and elaborates on how she, as the child of Holocaust survivors, has dealt with the atrocities of the Holocaust throughout her life. In her second memoir, Letting It Go, Katin expands this point of view and not only addresses the Holocaust from the view of the second generation, but adds another layer to dealing with the Nazi past, namely the point of view of the third generation. Accordingly, it is through Katin’s son, Ilan, that Miriam learns not to encounter Berlin stereotypically and embittered anymore. Modern day Berlin welcomes Katin and her family with open arms and is not comparable with the former capital of National Socialism anymore. Therefore, both graphic memoirs can be regarded as a process of coming to terms with the trauma of the Holocaust through the technique of self-reflexivity.

Keywords:

Katin; Miriam; Holocaust; graphic memoir; self-reflexivity; second generation; Hirsch; Marianne; postmemory; third generation 1. Introduction

Today, representations of the Holocaust are to be found in every field of (popular) culture, be it in movies, poems, exhibitions, music, or in literature. However, three decades ago, this omnipresence of cultural works on the Holocaust was not given. Holocaust studies as an academic field, for example, have permeated popular culture in the 1980s, (Hirsch 2012) with Claude Lanzmann’s documentary film, Shoah, which gained access into American living rooms in 1985 and consequently made the Holocaust accessible to a broader audience. It was also in this time period that comic book artist Art Spiegelman published his seminal graphic novel Maus, which consists of two volumes; My Father Bleeds History (1986) as well as And Here My Troubles Began (1991). In his work, Spiegelman deals with his familial experiences of the Holocaust and the impact the war has had on both him and his parents. Recording his father’s testimony about the Holocaust throughout the 1970s, Spiegelman has found an unconventional way to approach the difficult topic of the Holocaust by using anthropomorphic characters to represent Jews, Germans, and Poles in his work. Moreover, Carolyn Kyler in her article, “Mapping a Life: Reading and Looking at Contemporary Graphic Memoir,” reasons that Maus “marked the coming of age of the contemporary graphic novel” (Kyler 2010, p. 2).

However, prior to permeating popular culture with such representations of the Shoah, survivors remained silent about their war experiences for decades. In their study “Memoirs of Child Survivors of the Holocaust: Processing and Healing of Trauma Through Writing”, Adu Duchin and Hadas Wiseman elaborate on this topic that “survivors tried to tell about their life but nobody wanted to listen” (Duchin and Wiseman 2019, p. 2). Therefore, Duchin and Wiseman emphasize the importance for Holocaust survivors to write about their experiences and therewith find peace with their past. They explain, “one way survivors can tell their traumatic stories is by writing their memoir and publishing them in book form” (ibid.). Such an “activity of storytelling”, notes Ernst van Alphen in his essay “Second Generation Testimony, Transmission of Trauma, and Postmemory,” can greatly influence a survivor’s “healing” (van Alphen 2006, p. 474).

One such child survivor of the Holocaust is Miriam Katin, who survived the war with her mother by hiding in the Hungarian countryside from 1944–1945. Born in 1942, Miriam was a toddler when her mother decided to fake their murder after the situation for Jews worsened with the invasion of Budapest by the Nazis in 1944. After the war, Katin’s childhood was characterized by her family’s silence about their ordeal, resulting in the child’s “imaginative investment, projection, and creation” of the Holocaust (Hirsch 2012). After the war, under the pressure of the rising Communism in the country, Katin and her family moved to Israel where, according to Katin, “nobody talked about the war—nobody wanted to remember the war” (USC Shoah Foundation Visual History Archive 2018, 01:01:17). In this respect, Jews trying to speak about their Holocaust experience, were considered weak, as the young nation of Israel wanted to look forward and not carry the burden of the past. However, Katin was influenced by Spiegelman’s publication of Maus, which was a turning point in her handling of her familial trauma. About the influence Spiegelman’s Maus had on Katin, she explains,

He already got the prize for it and everything—Pulitzer Prize—(…) I saw it in the corner of a bookstore [in 1989], and it was down there this appalling thing. And I hated it, Jesus. And I didn’t even know what to do with it myself. And when I came back to New York, finally I faced it. I said. ‘Let’s see what this is’. (…) By the time in Israel, I did some comics for children, for children’s magazines (…). So when I saw Maus (…) I said to myself, ‘You know what? I can tell my stories. I can draw them.’ Cause, you know, the stories my mother told me, they were all like a running … you know, in my mind it was like a constant running stories. But I am not a writer and anyway I said ‘Who needs another Holocaust book, there are plenty of them’. But the stories were still there, like a narrative and I was saying it in the third person of them. (…) So I said I can draw them.(USC Shoah Foundation Visual History Archive 2018, 02:17:11).

As becomes evident from this citation, Art Spiegelman’s Maus has paved the way for other comic book creators to critically engage with their past by using art as an expressionist tool. In times of an increasing “Holocaust fatigue”, as Joshua Lambert (2017) calls the inundation of films and books on the topic, the genre of the graphic novel, argues Victoria Aarons in the introduction of her monograph Holocaust Graphic Narratives: Generation, Trauma and Memory, offered “a legitimate form of Holocaust representation” (Aarons 2020a, p. 1). Consequently, Katin has produced two graphic memoirs, We Are On Our Own (2006) and Letting It Go (2013), in which she confronts her familial Holocaust history and tries to come to terms with her inherited trauma. Therefore, this paper uses Marianne Hirsch’s concept of postmemory to demonstrate Katin’s try to recover from her inherited past through remembering and re-living the past with the help of her familial photo archive in We Are On Our Own, and ultimately finding healing through an intergenerational self-reflexivity in Letting It Go. With her two graphic memoirs, Miriam Katin joins the ranks of women graphic artists such as Alison Bechdel, Aline Kominsky-Crumb, Leela Corman, and Miriam Libicki, as Dana Mihăilescu rightfully writes in her essay “Performing the Gendered Self: The Stakes of Affect in Miriam Katin’s We Are On Our Own” (Mihăilescu 2010), thereby making women graphic novelists more visible in comics studies.

2. Graphic Memoirs

2.1. We Are On Our Own

Miriam Katin’s first graphic memoir, We Are On Our Own, which was published in 2006 by the Montreal-based publishing company, Drawn & Quarterly, thematizes a Jewish family’s escape and life in hiding during the Holocaust. Set in Budapest and the Hungarian countryside during the Nazi occupation between 1944 and 1945, We Are On Our Own centers around Esther Levy and her daughter, Lisa, the increasing disenfranchisement and ghettoization of the Hungarian Jews, and the two protagonist’s flight from Budapest and their eventual survival of the war.

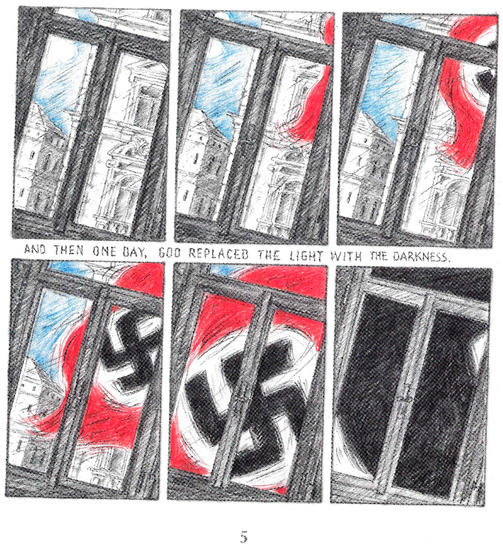

Miriam Katin opens her book, We Are On Our Own, with a proem to the actual narrative, thereby anticipating the events to follow in her graphic memoir. For this purpose, she uses a religious theme by borrowing a passage from Genesis 1:2, which she simultaneously has the omniscient narrator comment: “In the beginning darkness was upon the face of the deep. And God said: Let there be light. And there was light … And it was good. (…) And then one day, God replaced the light with darkness” (Katin 2006, p. 3 ff.). The first page of Katin’s book is devoted to the representation of the sentence, “In the beginning darkness was upon the face of the deep”, alluding to the creation narrative in the Torah. Stylistically, the sentence is placed in the middle of the page, surrounded by a thick frame drawn in heavy and disordered pencil lines. During the course of the next two pages, Katin continues with the foreshadowing of the events, i.e., Lisa’s and Esther’s war time experiences caused by National Socialism and the trauma that is going to haunt them for the rest of their lives.

Figure 1, for instance, draws attention to the contrast between the initial sentence, “Let there be light”, and the reversal thereof one page later, “And then one day, God replaced the light with darkness” (Katin 2006, p. 5). Divided into six commensurate, classically arranged panels, Katin represents the increasing threat posed by the Nazi regime slowly taking over Hungary. Stylistically, this is achieved through the symbolism of the Nazi flag. The latter slowly but inexorably appears from the corner of the second panel and continuously stretches over the next four panels until an oversized swastika sign is noticeable. The last panel is characterized by an extreme close-up of the swastika sign, producing a darkness hinted at on the first pages of the book. Following this, Katin uses the size and the prominence of the swastika sign to metaphorically herald the Jews’ experiences under Nazi occupation in Hungary.

Figure 1.

We Are On Our Own (Katin 2006). Reproduced by permission of Miriam Katin.

Following this prelude, the author begins her graphic memoir with the representation of the Jewish population of Hungary in 1944. On the macro level, Budapest is represented as a metropolitan city, “a city of lights, culture, and elegance”, as the narrator declares (Katin 2006, p. 7). For the depiction of her birthplace, Katin uses a scenic view of the city, which is stylistically realized by a rectangular panel taking half of the page alone. Zooming into the following two panels, it becomes apparent how modern Budapest is represented, as people amble along the Danube river, sit in cafés, and walk their dogs. On the micro level, however, this tranquility is being broken as soon as Katin starts to engage with the representation of the increasing marginalization and disenfranchisement of the Jewish population in Hungary one page later. As can be noted from a conversation between Esther and her non-Jewish friend, Eva, the former laments, “So, as I was saying, we can’t even own pets any more” (Katin 2006, p. 8). As a consequence, Esther has to hand over their family dog, Rexy, to Nazi soldiers greedily awaiting such dog breeds like Rexy (Schnauzer). Moreover, the worsening situation for the Jews in Budapest is represented by eviction notices, the command to list one’s belongings, as well as the rising antisemitism of the Hungarian population towards Jews in the country1. However, the treatment of the Hungarian Jews culminates in the regulation for their relocation into a newly established ghetto on the outskirts of the Hungarian capital, which is already a notorious place of avoidance among the Jewish population of the time2. Therefore, Katin’s and her mother’s alter egos, Lisa and Esther, stage their own deaths by spreading rumors of their suicide in the Danube river with the help of non-Jewish aides, eventually disguise themselves as a peasant mother with an illegitimate child, and consequently flee to the countryside. Here, the “duo [goes] door-to-door in the Hungarian countryside, begging anyone they [can] find to offer them refuge. In exchange, Levy offer[s] her sewing skills” (Kuznia 2019). In the countryside, then, mother and daughter encounter people helping them altruistically on the one hand, but also persons driven by avarice aiding them only for a service in return on the other. Since Lisa and her mother travel on their own3 through their home country, as Lisa’s nameless father is at the front, they repeatedly run the risk of being (sexually) assaulted by both Nazi and Russian soldiers.

By retelling her own and her mother’s escape story from Nazi-occupied Budapest in the graphic memoir, Katin heavily draws from her mother’s experiences during the time—be it her oral testimony or archival material, like letters and postcards available to her from the family archive. Katin shares this information with her readers in the epilogue of We Are On Our Own, in which she elaborates, “This book is the story of our escape and life in hiding during the year of 1944–1945. I could somehow imagine the places and people my mother told me about, but a real sense of myself as a small child and the reality and the fear of confusion of those times I could understand only by reading the last few letters and postcards my mother has written to my father” (Katin 2006, no pag.; emphasis added). In relation to Katin’s statement about somehow imagining places and people she was told about by her mother after the war, Diederik Oostdijk ties on exactly this self-referential remark by the author in his essay, “‘Draw yourself out of it’: Miriam Katin’s Graphic Metamorphosis of Trauma”, by noting, “Katin was born in 1942 and lived through the war herself. Yet, since children usually do not remember any childhood events before the age of three and a half, it is doubtful that Katin writes from personal experience” (Oostdijk 2018, p. 80). Therefore, Oostdijk reasons that, “It appears that Katin is drawing from an ‘imaginative investment and creation’ rather than relying on ‘recollection’” (ibid.; emphasis added). While Oostdijk assumes Katin’s imaginative investment and creation is inspired by her mother, this paper aims at verifying this assumption, as Katin herself states she “was there for that year, [i.e., 1944–1945], but I did not really ‘experience’ it. The story was told to me at about age 30 and the book is a recreation of my mother’s telling” (Miriam Katin, email correspondence; emphasis added).

In this regard, Marianne Hirsch in her seminal work, The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture After the Holocaust, published in 2012 by Columbia University Press, calls the aforementioned process ‘postmemory’4, which she defines as

[T]he relationship that the ‘generation after’ bears to the personal, collective, and cultural trauma of those who came before—to experiences they ‘remember’ only by means of the stories, images, and behaviors among which they grew up. But these experiences were transmitted to them so deeply and affectively as to seem to constitute memories of their own rights. Postmemory’s connection to the past is thus actually mediated not by recall but by imaginative investment, projection, and creation. To grow up with overwhelming inherited memories, to be dominated by narratives that preceded one’s birth or one’s consciousness, is to risk having one’s own life stories displaced, even evacuated, by our ancestors.(Hirsch 2012, p. 5; emphasis added).

Marianne Hirsch’s theory of postmemory, which connects the past “not by recall but by imaginative investment, projection, and creation”, can thusly be found in Katin’s first graphic memoir. The author ratifies Hirsch’s concept of postmemory in a video testimony for the USC Shoah Foundation Visual History Archive recorded in October 20185. In it, Katin stresses how the Holocaust and her familial losses lingered nonverbally on her childhood. Whenever she asked her parents or surviving relatives about their perished family members, the only monolingual answer she received was, “camps”, “They gone”, and “the war” (USC Shoah Foundation Visual History Archive 2018, 56:50). Accordingly, Katin’s childhood was overshadowed by a silence and vagueness of the Holocaust, which immensely added to her ‘imaginative investment [and] projection’ of the events in her works. In her paper, “The Cross-Generational Transmission of Trauma: Ritual and Emotion among Survivors of the Holocaust”, for instance, Janet Jacobs seizes upon this subject illustrating the psychological impact the Holocaust has had on second-generation survivors. Concerning this, she states, “Beginning in 1966, psychiatric and psychological studies of the second generation of Holocaust survivors described the children of survivors as suffering from nightmares, guilt, depression, fear and death, sadness, and the presence of intrusive images” (Jacobs 2011, p. 343). While not all mentioned symptoms necessarily need to manifest themselves in second-generation survivors, the overall findings of these studies reveal that the Holocaust “‘[had been] a dominant psychic reality’” (Bergman and Jacovy qtd. in Jacobs 2011, p. 343) for the latter. In accordance with Hirsch’s concept, earlier studies on the subject matter have also revealed the ways in which trauma is passed on from one generation to the other. In this regard, trauma is transmitted from the first to the second generation via parents obsessively telling their children about the Holocaust or being silent about it; the latter applies to Katin’s childhood experiences. This way of communication, or in Katin’s case, non-communication, deeply influenced Katin. While, on the one hand, “[p]arents shared, even with young children, the horrors to which they and their relatives had been subjected (…) deep emotional silences that are more difficult to articulate and assess, parental trauma was conveyed through (…) the [untold], feelings and emotions that permeated the survivor household,” aptly writes Jacobs (ibid.). In her video testimony for the USC Shoah Foundation Visual History Archive, Katin expresses how she reacted when she heard her family speak about the Holocaust for the first time within the frame of the Hungarian uprising to Communism in the 1950s:

And then my mother, father, my uncle and a friend were there and on the table … playing cards. What do you gonna do, you know? Play cards. And my uncle and the other friend stared to talk about the camps, the war. I was under the table playing with my cousin (…) and I just couldn’t believe it. Yeah. I heard a lot during that week. ‘Cause they were under pressure and stress and they were talking about it. I couldn’t deal with it at all. I couldn’t deal with those stories they were saying, but it stuck of course.(2018, 01:00:23).

Relating to this, and drawing on the concept of postmemory, this paper aims at underlining the dichotomy in the perception of the war by both Lisa and her mother, Esther, in We Are On Our Own, amongst others. When Esther Levy, for example, is approached both emotionally and physically by a Nazi officer, who is only referred to as “Herr Commandante” by the author throughout her work, Esther knows she must physically give in to his ‘advances’, which undoubtedly are to be classified as rape, otherwise their lives are endangered.

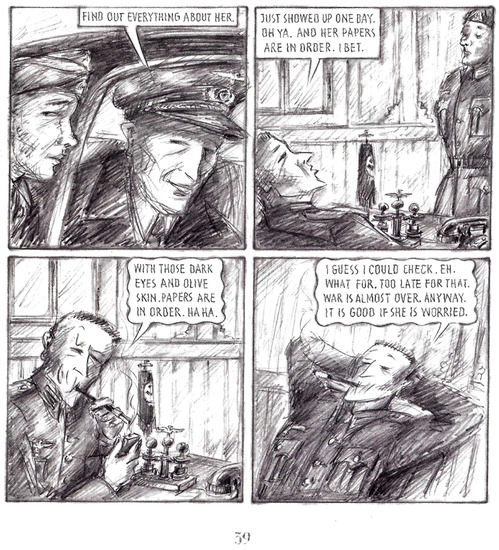

As can be seen in Figure 2, the Commandante takes advantage of Esther’s and her toddler’s situation by unscrupulously using the racist ideology propagated by the Nazis for his own (sexual) purposes. In line with this, he orders his nameless assistant to “[f]ind out everything about her” (Katin 2006, p. 39). Stylistically, Katin makes up the page of four classically ordered panels. The space between the panels, also known as ‘the gutter,’ is, according to Scott McCloud, characterized by human imagination. The latter, writes McCloud in his influential theoretical study, Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art, “takes two separate images and transforms them into a single idea” (McCloud 1994, p. 66). While “comics panels fracture both in time and space, offering a jagged, staccato rhythm of unconnected moments,” the practice of closure “allows [the reader] to connect these moments and mentally construct a continuous, unified reality” (McCloud 1994, p. 67). Hence, bringing into focus the first and second panel of the page, the reader can use their imagination—the practice of closure—to conclude that the Commandante’s assistant obeyed the order by standing at his attention, exclaiming, “Just showed up one day. Oh ya. And her papers are in order” (Katin 2006, p. 39). Ultimately, what follows in the third panel is a relaxed and content Commandante, lighting a cigarette in his office, which is full of Nazi symbols, alluding to the National Socialist racial laws of the time by confidently ruminating on Esther’s phenotype, “With these dark eyes and olive skin. Papers are in order. Ha. Ha”, and, metaphorically, having the whip in his hand (ibid.). In this instance, the Commandante’s thoughts about Esther’s ‘race’ are represented by the curvy contours of the speech balloon. Consequently, in the following fourth panel, the Nazi officer continues with his line of thoughts, which reveals his maliciousness to sexually take advantage of Esther’s fears of being reported to and eventually killed by the Nazis, “I guess I could check. Eh. What for. Too late for that. War is almost over. Anyway. It is good if she is worried” (Katin 2006, p. 39; emphasis added). Four pages further into the story, the Commandante is shown to button up his trousers in the third panel, while Esther lies in bed and covers her body with a blanket, grinningly asking Esther, “By the way, how would a simple servant speak German so well?”, upon which Esther submissively and sadly counters, “I worked for a German family” (Katin 2006, p. 43).

Figure 2.

We Are On Our Own (Katin 2006). Reproduced by permission of Miriam Katin.

By physically pleasing the German officer, Esther saves her own and her daughter’s life. Yet this life in hiding is in a stark contrast to the one she enjoyed before the war. This, for instance, is represented by Esther’s choice of clothing. “The change of clothing from a lady to a peasant girl,” observes Eszter Szép in her essay, “Graphic Narratives of Women in War. Identity Construction in the Works of Zeina Abirached, Miriam Katin, and Marjane Satrapi”, “also illustrates the freedom the mother gives up when she takes refuge in the country6” (Szép 2014, p. 28). Despite the Commandante’s ‘visits’ that cause a lot of despair and a feeling of helplessness in Esther resulting in repeated crying, Lisa, in her own childish and naïve way of thinking at the age of two, assumes her mother’s sadness stems from ‘her friend’ leaving her mother at regular intervals. What Lisa, however, does not understand is her mother’s obligation to have sexual intercourse with the German officer in order to survive. Hence, while Esther perceives the Commandante as her rapist over an indefinite time, and additionally as the begetter of her baby she eventually aborts, Lisa, in turn, appreciates his presence since it is accompanied by chocolates for Lisa and ‘such happiness’ for her mother. Similarly, in his essay “‘To Night the Ensilenced Word’: Intervocality and Postmemorial Representation in the Graphic Novel about the Holocaust,” Jean-Philippe Marcoux also interprets that “the gift [of the chocolates] is deceitful as it is a gateway to raping the mother” (Marcoux 2016, p. 204 f.). And yet, the discrepancy between the different levels of perception of this situation even result in Lisa’s infantile apotheosis of the Commandante by uttering hopefully, “Mmm. So good. Such a nice man. Maybe he is God. The chocolate God.” by delightfully eating her filled chocolates received by the Nazi officer

Interestingly, while in her early childhood Katin’s alter ego, Lisa, misses this point, Katin does include these ‘visits’ into We Are On Our Own as an adult several decades later. The reader, therefore, can assume her mother has told the grown-up Miriam about the real causes behind those ‘visits,’ which, in turn, have deeply influenced and traumatized the grown-up Miriam. By the same token, Marcoux interprets this dual perspective on the event by commenting, “It is only through the graphic novelization of her mother’s mediated experience that Katin can understand the violence of the act performed on her mother” (Marcoux 2016, p. 204 f.). Relating to this, in her video testimony for the USC Shoah Foundation Visual History Archive, Katin self-reflexively affirms, “My mother told me the stories when I was about 30 years old when my second child was born, and my husband thinks it changed me.” (2018, 49:02). Miriam Katin further elaborates on the traumatic effects her mother’s wartime experiences have had on her by ruminating,

Throughout my whole life, I feel like the history and what happened to our family, I feel as if I am pulling behind me a filthy, dirty cloak that I would love to throw away and can’t. And that things remind me about a war. Funniest, you know, is it cold? Is it hot? The rain, the shower drains, it can all bring it back, that think I don’t even remember really, of course, but the story’s [sic!], the reality, all the time.(47:24).

Describing her inherited past, Katin’s feelings culminate in the description of triggers provoking the stories and the reality of her childhood memories and imagination (ibid.). This inherited trauma with which the author has been dealing with for the rest of her life, can also be noted in the aesthetics of her graphic memoir. “The images that represent the past”, sharply notes Aarons in her book chapter “The Performance of Memory: Miriam Katin’s We Are on Our Own, a Child Survivor’s (Auto)Biographical Memoir,” “are increasingly indistinct as they are when they represent a danger that Katin can only ‘remember’ in her projected hold on such remote memory. Katin’s illustrations are characteristically softly drawn sketches” (Aarons 2020b, p. 39; emphasis added), which evoke in the reader associations with the works of German expressionist painter Käthe Kollwitz.

While there exist a handful of colorful panels in Katin’s graphic narrative, all of which have to do with Lisa’s and Esther’s future refuge, i.e., the United States of America, the rest of We Are On Our Own is held in black and white. “Delicate scenes”, writes Dana Mihăilescu (2015) in her essay “Haunting Spectres of World War II Memories from a Transgenerational Ethical Perspective in Miriam Katin’s We Are On Our Own and Letting It Go”, are “drawn in heavy pencil lines” (Mihăilescu 2015, p. 167), demonstrating the author’s inner conflict when imagining her mother’s experiences during the war in Hungary.

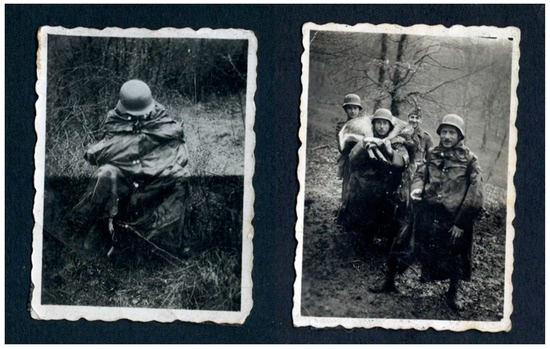

Moreover, Katin’s drawing style was influenced by two photographs her father carried with him while serving in the Hungarian Army, which scared and simultaneously also fascinated Miriam in her childhood (USC Shoah Foundation Visual History Archive 2018, 2:18:59).

The photographs in Figure 3 represent Katin’s father, who remains nameless in her narrative, trying to keep himself warm in an Army trench in the Carpathian Mountains in Romania (left), as well as his colleagues carrying a dead lamb on their shoulders, which was meant for supper, as can be learned from a recreated letter her father wrote to her mother in the graphic narrative (left).

Figure 3.

Katin’s father in the Army. Courtesy of the Katin Family Archive. Reproduced by permission of Miriam Katin.

Elaborating on the photographs, Katin elucidates in her video testimony, “The depth of the blackness in there (…) that’s what I wanted to reach on my pages [in We Are On Our Own]. That was very instrumental in finding my style, and the mood of the book—those two pictures” (2:19:32). Further commenting on her drawing style, Katin remarks, “it just came to me so natural” (2:17:73) and “[t]he style came with the story. I never had a style before, but I sat down, put my pen on the paper and it was just pouring out of me” (2:18:08).

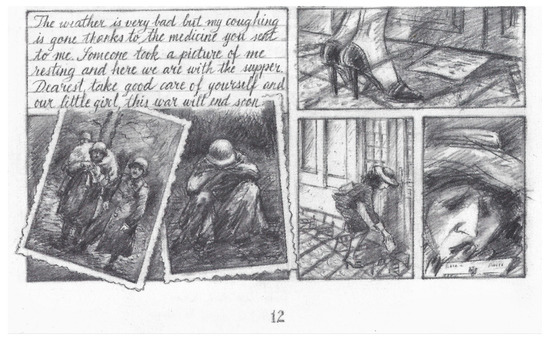

The importance of the family photo archive for Katin’s work can doubtlessly be observed from this passage. “My visual influences”, strengthens Katin in an interview published in Samantha Baskind’s and Ranen Omer-Sherman’s edited volume, The Jewish Graphic Novel: Critical Approaches, “are a number of old photographs that survived the war with my father. Especially the two I re-create on page 12 [in We Are On Our Own; cf. Figure 4]. Also, the photographs of our family members who never returned and I did not know” (241). Upon the use of photography in cultural texts by the second generation, Marianne Hirsch notices, “The key role that photographic images—and family photographs in particular—play as media of postmemory clarifies the connection between familial and affiliative postmemory, and the mechanism by which public archives and institutions have been able to re-embody and to re-individualize the more distant structures of cultural memory”. Hirsch goes on by noting that “photographic images are fragmentary remnants that shape the cultural work of postmemory” (Hirsch 2012, p. 36). In addition, Andrew J. Kunka further elaborates on the topic that photography is also used in autobiographical comics “as a gesture toward authenticity” (Kunka 2017, p. 72). El Refaie addresses this phenomenon as well by stating, “Unlike most of the more common comic genres, graphic memoirs frequently include photographic images and other forms of ‘documentary evidence’ in their works, whether in their ‘pure’ form or in a graphic rendering (…) [and] it is undoubtedly the photograph that places the most significant role in performing authenticity in the graphic memoir” (El Refaie qtd. in Kunka, p. 72). Correspondingly, as Katin herself aptly points out in her testimonial for the USC Shoah Foundation Visual History Archive, she recreates her familial history by imaginative investment, projection, and creation through the two pictures her father was able to rescue from the war.

Figure 4.

We Are On Our Own (Katin 2006). Reproduced by permission of Miriam Katin.

Following this line of argumentation about the importance of familial photographs, Katin incorporates, in her first graphic memoir, two important images that stick out through the course of the narrative, i.e., the cover image as well as the very last image in the book. On the cover of Katin’s memoir, for example, Aarons writes, “[I]t is a split panel; on the left is a drawing of the defeated Nazi banner in a heap in the ground, the image of the swastika partially obscured by the flag’s folds; on the right is a picture of mother and daughter, over whose heads flies a Soviet banner.” (Aarons 2020b, p. 48). Rounding off the structure of the book, the memoir ends with “a final parallel image to that on the cover” (ibid.). The picture the reader can see here is a recreation of an image Katin’s uses from her family archive. As a caption informs, it was taken in 1946 and shows Miriam’s mother smilingly holing her small child’s hand, while Miriam is standing next to her mother and both “look directly out of the frame as, together, they meet the viewer’s gaze” (ibid. 49). Hence, Aarons concludes, “While on the cover, the expression in the faces of mother and child are yet to be distinctly formed, as in their future, the final image at the close of the memoir shows them smiling in open embraces of a new and hopeful life” (ibid.).

And yet, while Aarons hints at a happy ending of the graphic memoir for both Katin and her mother, another passage in the epilogue deconstructs this benevolent outlook and is rather demonstrating the impact the specters of the past have had on both Katin and her mother ever since. In the respective section of the epilogue Karin writes,

Everybody is talking more about the war these days and so is my mother. The world she faced so bravely left her with great mistrust of places, systems, and institutions. She watched me creating this book with apprehension. When I would tell her, ‘Mom, everyone from this story is either dead or too old to care’ she would reply, ‘You never know. Someone might see it, take offense and come after us’.(Katin 2006, no pag.; emphasis added)

As the citation clearly demonstrates, the Holocaust still continues to haunt Katin’s mother, who is afraid to reveal their identities even after six decades. In an interview with Samantha Baskind, Katin comments, “‘There is an enormous fear in some of the survivors, like my mother, that someone will be offended and take revenge’” (Katin qtd. in Baskind and Omer-Sherman 2010, p. 241). As a consequence, the fear of Katin’s mother prompts the author to use pseudonyms of the characters in both her graphic memoirs.

2.2. Letting It Go—Or, Reconciliation

While ending her graphic memoir, We Are On Our Own, with an assessment of the wounds the war has left on her mother, the same traits reoccur in Katin’s second memoir, Letting It Go (Katin 2013). Leaving wartime Hungary behind and flashforward 60 years, Letting It Go also focuses on the relationship of two members of the Katin family. Unlike We Are On Our Own, however, which represents the bond between mother and daughter, Letting It Go centers around the relationship between the second and the third generation of Holocaust survivors, more precisely around Katin herself and her son Ilan. The story centers around Katin and how she tries to come to terms with her traumatic past when her grown-up son, Ilan, one day visits her in New York City to tell her about his plans to move to Berlin. In a personal email correspondence, Katin reveals that Letting It Go originated from “the rage [of] my son’s decision [to live in Berlin]” (Miriam Katin, email correspondence, 4 October 2020). Adding to it, Katin further declares in her oral testimony for the USC Shoah Foundation Visual History Archive that his choice of moving to the German capital city, “completely knocked me out of my … - I was terribly upset” (2018, 02:32:23).

Interestingly, the memoir oscillates between New York City, Katin’s home, and Berlin, her son’s abode. The narrative starts off where Katin’s last book ended—namely with the representation of the author’s mistrust towards all things German. This mistrust, which originated from the wartime experiences her parents had to endure, and which were passed on to Katin through “stories, images, and behaviours” (Hirsch 2012), also entails places, systems, and institutions. Hence, as can clearly be noted, Letting It Go and We Are On Our Own are characterized by a circular structure so that the books seem to complement each other by “bring[ing] together the war time memories of three generations of Holocaust survivors, i.e., child survivors, adult survivors and children of survivors” and their perception of the war (Mihăilescu 2015, p. 155) and the time thereafter.

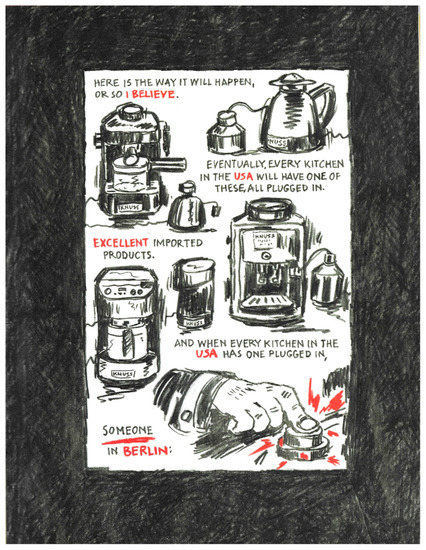

Letting It Go, also released by the Canadian publisher Drawn and Quarterly in 2013, opens with a single-page representation of kitchen machines by the fictional German brand ‘Kruss’ held in black and white.

As can be seen in Figure 5, the depiction of the kitchen utensils is surrounded by a thick border drawn in deep black, and disordered pencil lines. The borderless captions to this representation, for example, suggest a plot against Americans by an unknown Berlin-based institution or person with the intent of blowing up American kitchens. According to Dana Mihăilescu, Katin’s “choice of brand is not random, as [the author] in fact indirectly refers to the [German] ‘Krupp’ manufacturer of arms and ammunition, infamous for their use of slave labour during World War II” (Mihăilescu 2015, p. 156). Furthermore, the immediacy Katin wants to create with this picture is stylistically emphasized through red words like “USA” and “Berlin” in bold print and the lack of panels. At the same time, this aesthetic means also hints at the antagonistic stance both countries, Germany and the United States of America, hold in Katin’s mindset.

Figure 5.

Letting It Go (Katin 2013). Reproduced by permission of Miriam Katin.

The protagonist’s antipathy towards Germany, ultimately, intensifies throughout the book, as Ilan’s plans to move to Berlin take form. In addition to this, Ilan also intends to apply for a Hungarian citizenship to increase his chances of remaining in Europe.

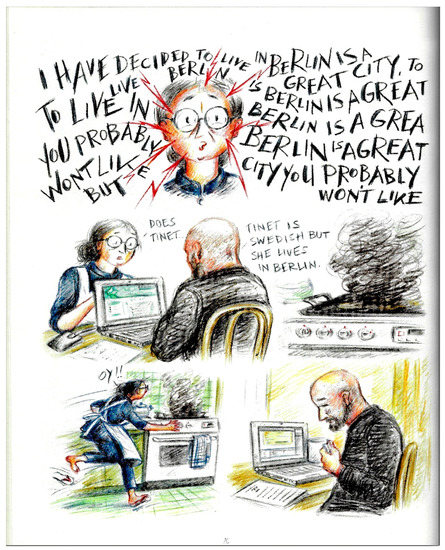

As noted in Figure 6, Katin’s shock about Ilan’s revelation is graphically captured by arrows pointing at her head, which is drawn in a close-up and takes almost one third of the borderless page layout. As can clearly be noticed, the protagonist’s negative feelings are mirrored in the respective drawing style. Oostdijk hereunto notes, “the more unsettled Miriam’s mind becomes the more irregular the page layout becomes” (Oostdijk 2018, p. 83). Interestingly,

by choosing her head rather than her heart to suggest her shock at Ilan’s decision, Katin underscores that what is at stake in Letting It Go is her largely unsuccessful attempt rationally to control her deeply internalized feelings [about the Holocaust mediated to her throughout her life].(Mihăilescu 2015, p. 159)

Figure 6.

Letting It Go (Katin 2013). Reproduced by permission of Miriam Katin.

Whereas her son thinks pragmatically about becoming a Hungarian citizen, Miriam immediately sarcastically replies to him that the Hungarians wanted to kill her and her mother during the war. In this regard, Dana Mihăilescu notices,

For Katin—the survivor of Nazi policies—Hungarian or German citizenship means an irrevocable threat to one’s security in light of the 1935 Nuremberg racial laws of Germany and the 1941 racial laws of Hungary which established who counted as Jewish as well as drastic limitations on Jews’ economic, social, and political rights.(Mihăilescu 2015, p. 159)

During Ilan’s request to fill out his application, the reader perceives Katin’s inner conflict with obliging to her son’s wish. Upon going through the questionnaire, Miriam’s inherited traumatic experiences of the war are triggered by every question. Thusly, she sarcastically laments:

About the grandparents, for example. As to who they were. Also, what was their last address. Well. They went ‘Arbeit’ and then they ‘Frei’-ed. Or Roasted. (…) This is like handing my baby over to the wolves.(Katin 2013, no pag.).

Katin’s struggle with filling out her son’s application for the Hungarian citizenship is portrayed by the protagonist sitting at her table at night, with a Martini next to her, and the documents spread all over the table. Miriam bows over the documents, her hair loosened, desperately holding her head with her hand. While going through the paperwork, Katin’s graphic novel character not only sarcastically comments on the questions asked, but the author also embeds the infamous entry sign to Auschwitz “Arbeit macht frei” (Katin 2013, no pag.) in her book. Stylistically, Katin uses a black and white drawing style to distinguish the past from the colorful present, which is “a way to prove how the artist’s view of Germany has kept the location frozen in time, at the level of World War II events” (Mihăilescu 2015, p. 157). Moreover, Katin abstains from classically arranged panels and uses a more open format for the page layout. This emphasizes the author’s emotions and her stream of consciousness in the process of her memoir, which, in turn, creates more authenticity to the narrative7.

And yet, while Ilan returns home after a night out in New York City at 1 A.M., he sees his mother bent over his documents, sleeping. The next morning, he tells his mother, “Mom, Mom. I threw it into the trash. I can’t ask this. I see what it’s doing to you.” (Katin 2013, no pag.). Throughout this episode in the graphic memoir, the reader learns Katin’s graphic novel character is not mentioning her sorrows and feelings to her son. Interestingly, a similarity between the first, second and third generation of Holocaust survivors sticks out in this part of the graphic memoir, namely the lack of communication, or silence. While Miriam’s mother did not talk to her child about her experiences during the war until the age of 30, (Miriam Katin, email correspondence, 2019), the grown-up Miriam also does not tell her son about her uneasy feelings while filling out Ilan’s application for a Hungarian citizenship. On a ubiquitous silence about the Holocaust and its impact on the family, Katin reveals, “I did try, as my parents did, to hide the facts from my children and in school there was not much about it. I wanted to save my children, as my parents did me from all the terrible reality” (Miriam Katin, email correspondence). The author’s utterance about shielding her children from the harsh reality of postmemory could be interpreted as Katin’s inability to deal with her and her parent’s past. Therefore, in Letting It Go, Ilan functions as an entity forcing his mother to come to grips with her (familial) past.

Ultimately, Miriam can only be dissuaded from her stance on Ilan gaining the Hungarian citizenship after meeting her friend, Betty, herself a Holocaust survivor, in New York City. Betty’s family fled to Argentina during National Socialism and her friend offers an alternative perspective on Ilan’s wish to Katin:

Concerning this matter, Katin is well aware of her presumable overreactions, as she self-reflectively calls herself a “manic old lady” in the acknowledgements of the book. Therefore, it might not surprise the reader that the first half of the book is devoted to the representation of Katin’s antipathy towards Germany. This antipathy becomes manifest in Katin’s representation of Berlin in 1945 amongst others and her repeated badmouthing even of things she actually likes, like, for instance, the German design of certain things during her first visit to Berlin. The protagonist’s deliberate suspicion of Germany even continues while Miriam and her husband, Geoffry, visit Ilan. While being invited by the Jewish Museum Berlin to exhibit her works and even by experiencing Germany’s ‘Vergangenheitsbewältigung’, its coming to terms with the Nazi past through countless memorials to the murdered Jews of Europe, Katin cannot abstain from sarcastically drawing parallels between almost everything she experiences and sees in modern-day Berlin and the Berlin of National Socialism.Listen Miriam. You are not protecting him. If he wants to live there, he will anyways. Illegally! With no rights. When our kids were born in Argentina, we arranged for them to get German citizenships through their grandparents. (…) See? They have choices. We gave them choices. Think about it.(Katin 2013, no pag.).

One example for the protagonist’s aversion for Germany is manifested in an experience she and Geoffry have in the Neue Synagoge Berlin, which has been turned into a museum. In order to enter the exhibition halls, Miriam and Geoffry need to undergo a security check for which all metal objects need to be taken off. After experiencing the Neue Synagoge and slowly but steadily starting to like present-day Berlin, Geoffry cannot find his wedding ring anymore and immediately blames the German security agent by incredulously exclaiming, “That can’t be! You mean here I am, a Jew visiting Germany, and somebody takes my gold wedding ring? (…) Those dirty Krauts! I bet somebody kept it!” (Katin 2013, no pag.). As becomes clear from this episode in the graphic memoir, Katin here draws parallels between her husband’s presumable stealing of his wedding ring and the Nazis’ theft of Jewish gold during the Third Reich. However, while shortly thereafter Geoffry’s ring wondrously reappears, Katin wants to incorporate their experience in her nascent graphic memoir. In a conversation she has with Ilan, she expresses, “(…) The ring was found, but in the story I’m working on, it will stay lost. (…). It will be meaner that way. I want it as nasty as possible” (Katin 2013, no pag.; emphasis added). However, Ilan here appeals to his mother’s conscience telling her, “But Mom, lying about the ring conveys this idea that we should continue to hold our prejudices based on history and not based on direct experience. We know you had a nice time in Berlin” (Katin 2013, no pag.). In fact, Ilan’s opinion about his mother’s intention on the plot of her graphic memoir are of avail, as the protagonists thinks over her plan. Hence, to paraphrase Carolyn Kyler, Ilan’s role in Letting It Go can be interpreted as a bridge between his mother’s imagination of Berlin (postmemory) and her reconciliation thereof; hence, Ilan functions as a mediator between Miriam’s imagination and her experience of Berlin and Germany (Kyler 2010, p. 12 f.).

From this moment on, the reader can perceive Miriam’s changed attitude towards Berlin and Germany by slowly acknowledging present-day Berlin cannot be compared to war-time Berlin that was frozen in her imagination over decades. The city, she realizes, has changed to a multicultural place welcoming a myriad of cultures and ethnicities. Hence, Katin self-reflexively admits in a conversation with her husband, “I guess the Germans have moved on and I didn’t” (Katin 2013, no pag.).

And yet, although Miriam slowly realizes the shift Germany has taken from the country of the perpetrator to a country critically engaging with its Nazi past, Miriam’s inherited trauma of the Holocaust still becomes apparent in physical reactions, which are

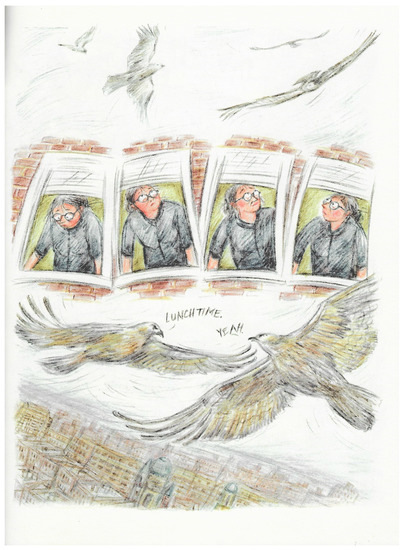

While, on the one hand, Berlin causes such strong physical reactions in Miriam, New York City, on the other, seems to be the author’s place of refuge, even her “comfort zone”, as Mihăilescu aptly formulates (p. 166). Interestingly, what accompanies Katin’s representation of the United States of America, more precisely her apartment in New York City, is the repeated portrayal of doves.first represented by a bout of diarrhea, and then by a rash only affecting herself, and not her husband. (…) [T]hese symptomatic reactions of Katin stand for her position as a young child survivor of the Holocaust for whom (…) embodied somatic traumatic memories of their World War II experiences predominated and, after the Holocaust, continued to influence how they related to the world.(Mihăilescu 2015, p. 166).

Doves, for example, not only appear within the narrative several times but they are also imprinted on the board. As the birds only emerge in combination with America, the latter can be understood as a signifier of freedom. Moreover, on another level of synesthesia, doves can also be understood as a symbol of peace. In the Bible, Michael Ferber elucidates in monograph, A Dictionary of Literary Symbols, Noah

sends a dove forth three times to find out how far the waters of the Flood have receded (…); the second time the bird returns with a fresh olive leaf in its beak, a sign that the waters have shrunk enough to reveal olive groves. In classical tradition the olive came to represent peace, and so had the dove (…).(Ferber 2007, p. 63)

Seizing upon the trope of freedom and peace, it can be concluded that Katin has incorporated doves, as can be noticed in Figure 7, in her second graphic memoir as to their ability to fly wherever they want. It is this independence that brings about the author’s disentanglement from the chains of her inherited past. Therefore, the trope of freedom is a clear aesthetic means Katin’s uses to portray her long way of reconciliation with her past. The latter is also emphasized by the dedication on the first page of the book. It thus reads, “Dedicated to the Past, Present, Future and the new Berlin” (Katin 2013, no pag.). In accordance with the liberating feeling of producing her second graphic memoir, Katin self-reflexively comments in her video testimony, “I just realized that I don’t quite think that much about it daily. It’s not as painful, not as burdensome as it was before I did the book. (…)” (USC Shoah Foundation Visual History Archive 2018, 02:32:23).

Figure 7.

Letting It Go (Katin 2013). Reproduced by permission of Miriam Katin.

3. Conclusions

To conclude, this paper has thematized the topic of postmemory and the transgenerational trauma of the Holocaust in Miriam Katin’s two graphic memoirs We Are On Our Own and Letting It Go. Special attention has been paid to investigating the technique of self-reflexivity as an instrumental copying mechanism in the creative process. As I have shown, Katin’s first graphic memoir constitutes the author’s first step of dealing with her inherited past by narratively and visually representing her mother’s ordeal during the Nazi occupation of Hungary from 1944–1945. In order to correctly capture the mood of the time Jews faced in Budapest, and in an attempt to do justice to her mother’s war time memories, Katin has opted for an (almost all) black and white drawing style. She uses the aesthetic means of recreating history by remediating photographs, letters, and postcards from her family archive, which she has read as an adolescent. In effect, the reader is confronted with material that the graphic novel uses to authenticate these memories. In line with this, Katin closely follows conventional stylistic elements in We Are On Our Own, i.e., the use of panel borders, the neat arrangement of the page layout, speech balloons, as well as the numeration of pages.

Visualizing the effects of the transmission of trauma, this paper has drawn on the theory of ‘postmemory’, first described by Marianne Hirsch in 1993. In her groundbreaking monograph, The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture After the Holocaust,” Hirsch defines the aforementioned concept as

[T]he relationship that the ‘generation after’ bears to the personal, collective, and cultural trauma of those who came before—to experiences they ‘remember’ only by means of the stories, images, and behaviors among which they grew up. But these experiences were transmitted to them to deeply and affectively as to seem to constitute memories of their own rights. Postmemory’s connection to the past is thus actually mediated not only by recall but by imaginative investment, projection, and creation. To grow up with overwhelming inherited memories, to be dominated by narratives that proceeded one’s birth or one’s consciousness, is the risk of having one’s own life stories displaced, even evacuated, by our ancestors.(Hirsch 2012, p. 5)

Secondly, this study has demonstrated how far Katin’s graphic memoir Letting It Go conveys the author’s inherited trauma that her parents have transferred to her non-verbally, silently evoked on the one hand, and creatively reimagined on the other, as Katin has involuntarily overheard a conversation about the camps and the Holocaust by her parents while playing under a kitchen table as a child.

As this paper has revealed, Letting It Go centers on how Katin tries to come to terms with her son’s plans to move to Berlin. While the author uses half of her memoir to express her prejudices toward Berlin, once she has visited the city and has encountered its ‘Vergangenheitsbewältigung,’ (its coming to terms with the past), the protagonist starts to like the place. However, as has become clear through this study, Katin still grapples to let go of her negative image she has internalized over the last three decades. Yet, strikingly, Ilan functions as an entity of reconciliation for Miriam, as his wish to move to Berlin and to become a Hungarian citizen forces Miriam to engage with the German capital on a personal level when visiting him. While, in We Are On Our Own, Katin has stuck to a conventional drawing style in view of looking back at her mother’s experiences of the Holocaust, Letting It Go takes a more liberal approach. In fact, she uses a more experimental drawing style, eschewing panels, speech balloons, and, for instance, page numbers. Contrary to the seriousness mirrored in the choice of colors in We Are On Our Own, Letting It Go is characterized by colorful drawings, which are occasionally surpassing page layouts. Thus, as has become clear in this paper, at the beginning of her dealing with her memoir, Miriam Katin looks for recovery through remembering and re-living the past with the help of her familial photo archive, whereas in Letting It Go she finds healing through an intergenerational self-reflexivity. This is best embodied by the preface found in Letting It Go: “Dedicated to the Past, Present, Future and the new Berlin” (Katin 2013, no pag.).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

Andrea Schlosser gratefully acknowledges the USC Shoah Foundation for allowing her to use transcripts of the following testimonies: [Miriam Katin, (2019)]. Further thanks are due to Dana Mihăilescu for her counseling during the development of this study. Last but not least, the author also wishes to thank Miriam Katin for the correspondence, her willingness to help, and the sense of humor Mrs. Katin has showed during the production process of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Aarons, Victoria. 2020a. Introduction: Visual Testimonies of Memory. In Holocaust Graphic Narratives: Generation, Trauma, and Memory. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Aarons, Victoria. 2020b. The Performance of Memory: Miriam Katin’s We Are on Our Own, a Child Survivor’s (Auto)Biographical Memoir. In Holocaust Graphic Narratives: Generation. Trauma, and Memory. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, pp. 17–51. [Google Scholar]

- Baskind, Samantha, and Ranen Omer-Sherman, eds. 2010. The Jewish Graphic Novel: Critical Approaches. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Duchin, Adi, and Hadas Wiseman. 2019. Memoirs of Child Survivors of the Holocaust: Processing and Healing of Trauma Through Writing. Qualitative Psychology 6: 280–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferber, Michael. 2007. Dictionary of Literary Symbols, 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch, Marianne. 2012. The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture After the Holocaust. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, Janet. 2011. The Cross-Generational Transmission of Trauma: Ritual and Emotion Among Survivors of the Holocaust. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 40: 342–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katin, Miriam. 2006. We Are on Our Own. Montreal: Drawn & Quarterly. [Google Scholar]

- Katin, Miriam. 2013. Letting It Go. Montreal: Drawn & Quarterly. [Google Scholar]

- Kunka, Andrew. 2017. Autobiographical Comics. Bloomsbury Comics Studies. New York: Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Kuznia, Rob. 2019. USC Shoah Foundation Redoubles Efforts to Collect Testimonies of Holocaust Survivors before It Is Too Late. USC Shoah Foundation. September 6. Available online: https://sfi.usc.edu/news/2019/07/25866-usc-shoah-doundation-redoubles-efforts-collect-testimonies-holocaust-survivors-it (accessed on 13 October 2019).

- Kyler, Carolyn. 2010. Mapping a Life: Reading and Looking at Contemporary Graphic Memoir. CEA Critic 72: 2–20. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, Joshua. 2017. How Comics Help Us Combat Holocaust Fatigue. Forward. February 2. Available online: https://forward.com/culture/361784/how-comic-help-us-combat-holocaust-fatigue/ (accessed on 17 April 2020).

- Marcoux, Jean-Philippe. 2016. ‘To Night the Ensilenced Word’: Intervocality and Postmemorial Representation in the Graphic Novel about the Holocaust. In Visualizing Jewish Narrative: Jewish Comics and Graphic Novels. Edited by Derek Parker Royal. New York City: Bloomsbury, pp. 199–218. [Google Scholar]

- McCloud, Scott. 1994. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. New York City: Harper Perennial. [Google Scholar]

- Mihăilescu, Dana. 2010. Performing the Gendered Self: The Stakes of Affect in Miriam Katin’s We Are on Our Own. In American Visual Memoirs After the 1970s: Studies on Gender, Sexuality and Visibility in the Post-Civil Rights Age. Bucharest: Bucharest University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mihăilescu, Dana. 2015. Haunting Spectres of World War II Memories from a Transgenerational Ethical Perspective in Miriam Katin’s We Are on Our Own and Letting It Go. Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics 6: 154–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oostdijk, Diederik. 2018. “Draw Yourself Out of It”: Miriam Katin’s Graphic Metamorphosis of Trauma. Journal of Modern Jewish Studies 17: 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szép, Eszter. 2014. Graphic Narratives of Women in War: Identity Construction in the Works of Zeina Abirached, Miriam Katin, and Marjane Satrapi. International Studies. Interdisciplinary Political and Cultural Journal 16: 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USC Shoah Foundation Visual History Archive. 2018. “Miriam Katin”. In USC Shoah Foundation Visual History Archive. Los Angeles: USC Shoah Foundation, October 22, Available online: https://sfiaccess.usc.edu/Testimonies/ViewTestimony.aspx?RequestID=3d990730-8f05-4069-ad29-7edc7d146ee0&fbclid=IwAR3oFQ6BWdzyhHTgW4-ni_VZnBgwoDL6E84WmoP_maNFEcxOFIy-w4kq2Bo (accessed on 21 October 2019).

- van Alphen, Ernst. 2006. Second-Generation Testimony, Transmission of Trauma, and Postmemory. Poetics Today 27: 473–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | A representative for the rising antisemitism among Hungarians towards their Jewish citizens, is the character of ‘Herr Baross,’ Esther’s landlord, who pretends to only follow orders but secretly insulting Esther and her family as “Dirty Jews” (Katin 2006, p. 13). |

| 2 | In this regard, Esther Levy has heard rumors about deportations and disappearing people, so that she arranges for her and her daughter to flee with false papers. |

| 3 | One possible way of interpreting the title of Katin’s first graphic memoir, is thanks Esther’s and Miriam’s circumstance of fleeing, namely on their own. |

| 4 | Marianne Hirsch’s concept of ‘postmemory’ originated from her own experience at a time when the Holocaust slowly but steadily entered mainstream society between the end of the 1970s and the 1980s. This phenomenon manifested itself on college syllabi and an increase in television programs and films of the topic, like Claude Lanzmann’s documentary Shoah (1987) or the television series Holocaust (1978). The same year PBS aired Lanzmann’s documentary, for instance, Marianne Hirsch started teaching Holocaust memory through Art Spiegelman’s graphic novel Maus (1986). The work was of particular interest to her because, “(…) [T]here was something else that drew me in as well: Artie’s person, the son who did not live through the war but whose life, whose very self, was shaped by it. I identified with him profoundly, without fully realizing what that meant.” (Hirsch 2012, p. 9). During the process of establishing her groundbreaking and generic theory, Hirsch notes, “I was writing as someone who had inherited the legacy of a distant and incomprehensible past that I was only just beginning to be ready to study and to try to understand from a larger historical and generational perspective” (Hirsch 2012, p. 13 f.). Explaining her motivation for entering the field of memory studies, Hirsch points out, “(…) it offered a means to uncover and to restore experiences and life stories that might otherwise remain absent from the historical archive. (…) As a form of counter-history, ‘memory’ offered a means to account for the power structures animating forgetting, oblivion, and erasure and thus engage in acts of repair and redress” (Hirsch 2012, p. 15 f.). |

| 5 | Access to Katin’s video testimony is granted to several research institutions and universities around the world. |

| 6 | In the beginning of the graphic memoir, Esther Levy is represented as a fashionable woman who still experiences the liberty of meeting her friend Eva, watching the world go by in a Budapest café, and joking about Jewish dogs and their circumcision. However, this lighthearted life comes to a close when Esther decides to go into hiding. Disguised as a peasant woman passing a group of Nazi soldiers calling her indecent names, she acts empowered in order not to get caught. |

| 7 | On the production process of Letting It Go, which took Katin several years to finish, Katin explains it was like a “constipation,” therewith borrowing the term which was coined by Alison Bechdel during a personal conversation between the two female graphic artists (Interview, USC Shoah Foundation Visual History Archive, 02:38:00). |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).