Writing Lifestories: A Methodology Introducing Students to Multicultural Education Utilizing Creative Writing and Genealogy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Origin of the Course

- Organize their experiences and write personal stories.

- Interview family members (and others) and capture their experiences in your own prose.

- See and experience the world as those who came before them may have seen and felt it in order to understand ancestors hopes, dreams, and fears.

- Reflect upon how family history affected their lives in order for them to gain the insights needed to capture the interior life of a culture from whence they came.

- Explain to others that regardless of what heritage we come from, ALL are part of rich and varied backgrounds and intersecting cultures have become a part of the complex American cultural landscape.

- Research historical materials in order to put their own lifestories into the context of a wider world around them and take responsibility for the space that they occupy.

- Produce writings that will hopefully become valued family resources and treasures.

3. Designing the Course for a New Generation

4. Interpretations about the Literature and My Pedagogical Decisions

“Read: The Rice Room: Number Two Son to Rock and Roll by Fong-Torres

Written assignment: Write 2–4 pages in a typewritten, double spaced paper. Do any of the topics Torres writes about ring a bell with you? (e.g., your relationship with your parents today (Prologue). Do certain foods remind you of “home?” Your parents? Certain childhood experiences? (Chapter 1). Are names, or what we call ourselves, an issue with people with “different” sounding names? What was your relationship with your siblings? What were your childhood passions? Have you ever openly defied your parents as Fong-Torres did?

Written Assignment: Now, write a 3–4 page paper about your grandparents. Do some research on historical/political context. If your grandparents are not available to interview, interview your parents to learn what they remember about them, or even a friend of the family or a contemporary of your parents/grandparents. Look up historical incidents mentioned by your contacts”.(p. 3)

- Diverne’s House

- The house of myth;

- the house that shame built;

- the house given to Diverne.

- The myth of a slave woman

- Who had to be broken,

- but bore Two children,

- neither Negro nor white.

- The myth of their father.

- Panola: My Kinfolks’ Land

- As the toilers laid their tools down for an endless rest.

- It’s on this site that my soul breathes to harvest my best.

- For what was planted by those before me will forever stand.

- On this rural countryside called Panola, my kinfolks’ land.

It’s the ragged source of memory, a tarpaper-shingled bungalow in a weedy ravine

Nothing special: a chain of three bedrooms and a long side porch turned parlor where my great-grandfather, Pomp, smoked every evening over the news, a long sunny kitchen where Annie, his wife measured cornmeal dreaming through the window across the ravine and up to Shelby Hill where she had borne their spirited, high-yellow brood…

- …As much love,

- As much as a visit

- To the grave of a known ancestor,

- The homeplace moves me not to silence But to righteous, praise Jesus song:

- …Oh, catfish and turnip greens,

- Hot-water cornbread and grits

- Oh, musty, much-underlined Bibles; Generations lost to be found, to be found.

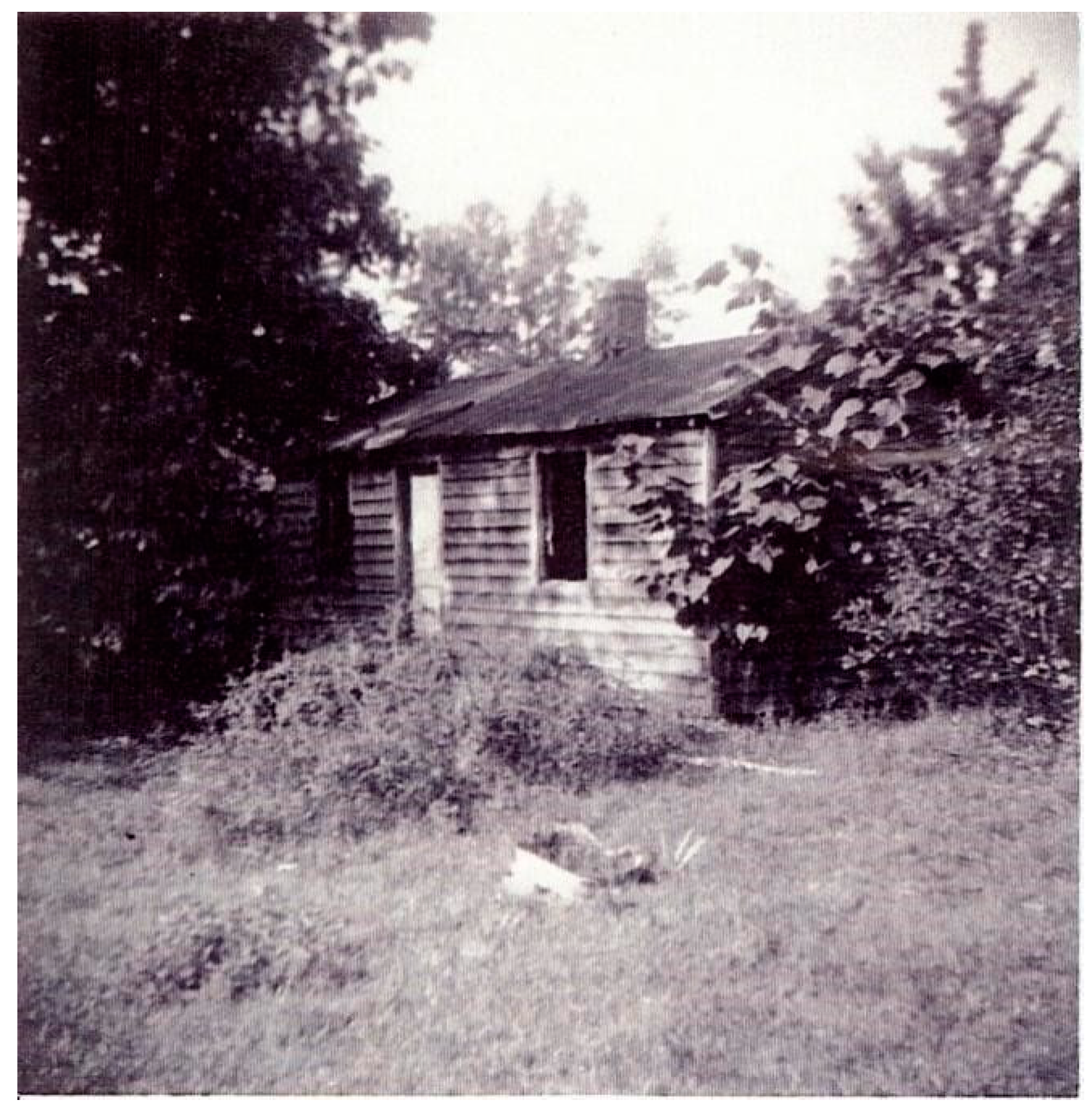

The family’s homestead (Figure 1) is located in Richmond County, the village of Warsaw (near Lyells), Virginia. Isabelle Newton (my great, great, great grandmother) bought this land as a result of saving money from the wages she earned as a midwife. The land—a total of 6 to 8 acres—was purchased from the Carter family (“… good White people”) for $40.

“…site of the ancestor…The role of the ancestor in Southern sections…

Is of great significance because it stress(es) the significance of an ancestor, or the blood… a place where Black blood earns a Black birthright to the land, a locus of history, culture… a place of birthright… a significant Influence in the migrant’s life in the North.”

Who Set You Flowin? (Farah Jasmine Griffen 1995)

“…the Black South’s religiosity… provided psychic health for Blacks by assuring them that they would not always be oppressed in the “Egyptland” of the Jim Crow south [but] equipped Southern Blacks with an indigenous belief system for hastening and contributing to their own liberation.”

“Reading assignment: “First Memories”, in Hong’s Growing up Asian American: An Anthology (Hong 1993, pp. 21–123). Some of the memories described in these short excerpts may help you in your interviews with your parents/grandparents about their childhood memories. Interview your grandparents or your parents, or both. If your grandparents are not available to interview, interview your parents to learn what they remember about their own childhood, or even a friend of the family or a contemporary of your parents or grandparents.

Short introduction to the readings.

Discussion of possibilities: How to begin research on your own family. Genealogical Research. Make plans for interviews; i.e., collect materials immediately accessible to you.

Write down names of family members you can consult, names of family friends and contemporaries of parents, grandparents.”.(p. 3)

“Guidelines for Library Research

There are three Library Research Days when you will report to the library to research materials for your Family History Book. Take advantage of the time and explore the library resources such as Ancestry.com, Dr. Christine Sleeter’s blog (https://christinesleeter.org/critical-family-history/), and any other library resources. Use the following guidelines to assist you with the research:

Research the historical background of the period: major news events, prominent political figures, economic or religious trends.

Collect visual images, old family photographs if available, if not, other images in books and magazines. Describe what the world must have looked like to your ancestors: Architecture, street signs, dress and hair styles, advertising, and foods.

Research cultural milieu: Artistic trends, best seller books, popular songs, jokes, recreational activities, games, movies, medical practices. Submit the primary sources where available into GeorgiaView (i.e., letters, newspapers clippings, documents).

Sign of the times: Speculate on the hopes, dreams, fears of the period. Examine the editorial sections of the newspapers, letters”

5. Reflections Upon the Initial Implementation

Conclusions

- Cousin P

- Or should I call her Cousin Suicidal-out there in

- Mormonville, UT

- But a girl’s gotta get edukated!

- ~smile~

- Anyway, it was GrandPop’s viewing

- I knew all of 8 people in the room

- I was nervous and needless to say not looking forward to sitting in a room with a “body”

- Not my Pop

- Shoooooot, we used to watch Soul Food on HBO

- He called them “the stories”

- He introduced me to a new word: “bulldagger”

- That was a brand new word

- He used to watch Moesha, Hardball with Chris

- Matthews and Judge Mablean all at once

- Thats right, 3 tv’s on at the same time

- I was blessed enough to meet him in ‘97

- He and my mother had the same smile My mother showed me forgiveness through her relationship with him

- He was a cool dude-and he knew it

- “These are Stacey Adams… the only shoes I wear”, he informed me with that Grandaddy arrogance and charm once, when I complimented him on his shoes

- Saying goodbye to him messed me up

- But God was with me

- And so was Cousin P

- Before I stepped a foot into the room

- I looked up and there was my cousin Paulette My cousin who’d spent all of 8 min with me my whole life

- I just knew her cause I’d never ridden in a Benz til she came to visit

- She walked me over to the casket

- And when I was about to crumble, she was next to me literally holdin me up

- God just sent her-

- And the two of them were right on time.

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Assignment | Length and Format | Contribution to Argument Construction |

| #1 A Collection of Memories | Brainstorming over 2–3 pages | Initial writing process brainstorming draft of family history and historical contexts |

| #2 A Response to Partner Scholar Presentations | Reflection of 2–3 pages | Synthesis and analysis of material presented by a range of scholars |

| #3 A Memorable Incident in My Life | Reflection of 2–4 pages | Data collection and synthesis |

| #4 Interview with a Family Member | Data collection and initial analysis. Length will vary, but likely 2–4 pages | Learning to synthesize specific data sources within broader contexts. Students work on identifying facts with accuracy, connecting to other sources, and beginning to identify theme. (Family member’s perspective). |

| Midterm Table of Contents | Midterm outline, 1–2 pages | Synthesizing key data and initial thesis construction. |

| #5 Profile of a Family Member | Reflection that may also include images, approximately 2–4 | Synthesis toward the ultimate argument by practicing with the data from one participant. (Student’s synthesis of multiple data sources to present a family through image and/or text.) |

| #6 Narrative of Findings | Reflection of 2–4 pages in a scholarly paper format | Connecting interview data as well as research from primary and secondary sources to begin a deeper synthesis leading to the overarching thesis and argument. |

| #7 An Analytical Essay | Reading response of 2–4 pages | Students respond to specific readings and model scholarly texts (e.g., Bell Hooks’ Yearning: Race, Gender and Cultural Politics). The assignment requires students to read and respond to scholarly work written in a similar format to their culminating project. |

| #8 National Identity | Reflective reading response of 2–4 pages | This assignment guides students to examine their ethnic identity and how it relates to family history and context. This is a seminal assignment for the scholarly connection between individual families and broader social and political contexts. |

| #9 Conclusion | Synthesis for inclusion in the culminating project, 2–4 pages | This is the final “chapter” or writing selection in the culminating book project. This is the location of the overarching argument each student constructs for their family history book. |

| #10 Bibliography | Annotated bibliography, varied in amount of pages. (approximately 2 pages) | Students articulate and annotate how they have engaged in a full review of related literature and sources to identify the five (5) most important scholarly sources used for their projects. This includes primary and secondary source materials of historical books and articles, cultural research, and genealogy. Students must evaluate each source for relevance, authority and format. |

| Final Culminating Book | Initial and final draft of the culminating family history book | Course synthesis and argument presentation. These books are shared in the library with an abstract and full text showcase. |

References

- Alby, C. 2019. Design for Transformative Learning. Semester-Long Program. Milledgeville: Center for Teaching and Learning, Georgia College & State University. [Google Scholar]

- Caron, Timothy P. 1996. The-reds-are-in-the-Bible-room-political activism and the Bible in wright, Richard ‘uncle tom’s children’. Studies in American Fiction 24: 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, P. 1997. WARSAW: The Newton-Patrick-Smith Family History Book. Unpublished book. Irvine: University of California at Irvine. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, Paulette Theresa. 2014. HOMEPLACE: Unearthing and Tracing the Oral Traditions and Subjugated Knowledge of a Multi-Generational Woman-Centered African American Family. Ph.D. dissertation, The University of Utah Education, Culture & Society, Salt Lake City, UT, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Dilworth-Williams, Evelyn. 2002. Panola: My Kinfolks’ Land. Bloomington: AuthorHouse. [Google Scholar]

- Fong-Torres, Ben. 1994. The Rice Room: Growing Up Chinese-American from Number Two Son to Rock ‘n’ Roll. Berkely: University of California. [Google Scholar]

- Georgia College & State University. 2019. GC1Y 1000: Critical Thinking: Writing Lifestories—Discovering Cultural Heritage Syllabus. Milledgeville: Paulette Cross. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, Natalie. 1996. Writing Down the Bones. Boulder: Shambhala Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Maria. 1993. Growing Up Asian American: An Anthology. New York: W. Morrow. [Google Scholar]

- Hooks, Bell. 1990. Homeplace: A site of resistance. In Yearning: Race, Gender, and Cultural Politics. Boston: South End Press. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, Toni. 1995. The Site of Memory. In Inventing the Truth: The Art and Craft of Memoir, 2nd ed. Edited by William Zinsser. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin, pp. 83–102. [Google Scholar]

- Trueblood, Kathryn, and Linda Stovall. 1996. Homeground. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan: Before Columbus Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, Alice. 2002. Everyday Use. New York: Knopf Publishing Group. [Google Scholar]

- Waniek, M. N. 1990. The Homeplace. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yamada, Mitsuye. 1997. Asian Am 110/Com Lit 103: Asian Americans Writing Lifestories: Discovering Cultural Heritage Syllabus. Irvine: The University of California at Irvine: School of Humanities. [Google Scholar]

- Yamada, Mitsuye. 1999. Asian Am 110/Com Lit 103: Asian Americans Writing Lifestories: Discovering Cultural Heritage Syllabus. Irvine: The University of California at Irvine: School of Humanities. [Google Scholar]

- Yamada, Mitsuye. 2000. Asian Am 110/Com Lit 103: Asian Americans Writing Lifestories: Discovering Cultural Heritage Syllabus. Irvine: The University of California at Irvine: School of Humanities. [Google Scholar]

- Yamada, Mitsuye. 2003. Asian Am 110/Com Lit 103: Asian Americans Writing Lifestories: Discovering Cultural Heritage Syllabus. Irvine: The University of California at Irvine: School of Humanities. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cross, P.T. Writing Lifestories: A Methodology Introducing Students to Multicultural Education Utilizing Creative Writing and Genealogy. Genealogy 2020, 4, 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy4010027

Cross PT. Writing Lifestories: A Methodology Introducing Students to Multicultural Education Utilizing Creative Writing and Genealogy. Genealogy. 2020; 4(1):27. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy4010027

Chicago/Turabian StyleCross, Paulette T. 2020. "Writing Lifestories: A Methodology Introducing Students to Multicultural Education Utilizing Creative Writing and Genealogy" Genealogy 4, no. 1: 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy4010027

APA StyleCross, P. T. (2020). Writing Lifestories: A Methodology Introducing Students to Multicultural Education Utilizing Creative Writing and Genealogy. Genealogy, 4(1), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy4010027