Abstract

Community based participatory research and attention to cultural resilience is recommended in HIV prevention research with Indigenous communities. This paper presents qualitative findings from evaluation of a culture-centered HIV prevention curriculum for Indigenous youth that was developed using a community based participatory research approach. Specifically, the authors focus on youth descriptions of cultural resilience and enculturation factors after participating in the curriculum. Thematic analysis of in-depth interviews with 23 youth participants yields three salient themes associated with cultural resilience and enculturation factors including: Development of cultural pride, honoring ancestors through traditional cultural practices, and acknowledging resilience and resistance within Indigenous communities. Additionally, per community directive, the authors share an observation of changes to identity descriptions from pre-curriculum baseline to post-curriculum interviews, pointing to a possible increase in awareness of Indigenous cultural identity.

1. Introduction

Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) is a research approach centering partnership and collaboration between researchers and community participants throughout all aspects of the research project (Israel et al. 1998; Wallerstein and Duran 2006). Participatory research processes are described as having a goal of “learning for change” (Abma et al. 2019). That is, participatory approaches in research aim to improve the systems within which they operate and, ultimately, change is produced and directed by the community stakeholders as they guide the process of the research (Abma et al. 2019). CBPR has been used over the last several decades to address health disparities (Burke et al. 2013; Israel et al. 2005; Wallerstein and Duran 2006) and focuses on the interconnected goals of action, education, and research (Wallerstein and Duran 2017). Among Indigenous communities, specifically, CBPR has been utilized as a research approach to address health inequities and health promotion through engaging stakeholders and community members in culturally responsive approaches to research (Dickerson et al. 2018; Dignan et al. 2014; Mau et al. 2010). CBPR projects in Indigenous communities have been successful in centering relationships, collaboration, and sustainability within communities and have allowed for culturally-specific adaptations and iterative and fluid modifications to the research (Brockie et al. 2017; Mau et al. 2010). Moreover, CBPR is emphasized as a recommended approach for HIV research with Native and Indigenous communities (Walters et al. 2011).

In 2013, an informal community survey conducted at a grassroots annual HIV prevention event, held in an urban area of the Rocky Mountain region, entitled “Rise Up!” yielded a call from community members to increase HIV prevention education for the community’s Indigenous youth. Responding to this call, researchers and the organizations that participated in hosting the annual event used a CBPR design to develop and evaluate a culture-centered HIV prevention curriculum for Indigenous youth, which was funded in 2014 and implemented in 2015. The curriculum addressed the multiple prongs of HIV health risk while centering positive cultural identity development. This paper reports qualitative findings from evaluation of this culture-centered HIV prevention program with a focus on youth descriptions of enculturation factors embedded in the curriculum.

We begin with a brief description of HIV risk in the population. Then we describe our approach, rooted in CBPR, to develop the HIV prevention curriculum in collaboration with community partners focusing on how we integrated enculturation factors into the curriculum modules. Next, we report findings related to three themes emerging from post-curriculum interviews: Developing cultural pride, honoring ancestors through traditional cultural practices, and acknowledging resistance and resilience. We conclude with a brief discussion on observations related to shifts in identity descriptions from the pre-curriculum baseline demographic form to post-curriculum interviews.

This paper uses the term “Indigenous” as a tool of inclusivity for the targeted participants. Community partners identified this as an important value as they work to serve all Indigenous communities regardless of federal tribal status. The term here encompasses all Indigenous peoples of the Western hemisphere that may live in or around the study area (an urban area of the Rocky Mountain West), including but not limited to: AI (American Indian), First Nations, Latinx of Indigenous descent such as Mexican American Indians, Central American Indians, South American Indians, as well as individuals of mixed race Indigenous heritage. It is important to note that this specific urban area has a unique experience of group integration within the AI and Latinx communities, historically seen as separate but who are known to have shared histories with similar experiences of colonization. Part of that is related to the area’s status as the largest hub for urban Indigenous communities within a 200-mile radius, proximity to the southwest, and the intersectional identity experiences common to AI and Latinx communities in the region. Due to absent epidemiological data on Indigenous Latinx communities singularly, we present HIV prevalence in both American Indian and Alaska Natives (AIAN) and Latinx populations to provide the foundational background for the issue.

2. Background of HIV/AIDS in Indigenous Communities

Indigenous communities globally are disproportionately affected by HIV/AIDS (Purdy 2013). In the United States, when diagnosed with AIDS, AIAN have shorter survival times than Whites, Asian and Pacific Islanders, and Hispanics (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] 2016; Walker et al. 2015). HIV diagnoses for both Hispanic/Latino and AIAN increased between 2013 and 2018 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] 2019c). Further, during that five-year time period, the gap between diagnoses for both AIAN and Hispanic/Latino populations and White populations also increased (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] 2019b). Among LGBTQ populations, in 2016, the greatest number of new HIV diagnoses were among men who have sex with men (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] 2018) and within this group, those aged 13–29 accounted for nearly 50% of diagnoses (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] 2018). AIAN diagnoses for MSM within this age range increased 14.8% annually between 2008 and 2016 and 4.5% for Hispanic/Latinos (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] 2018). These increases are disproportionately high given the national annual increase for this segment of the population was 3% (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] 2018), and indicates the need for HIV prevention programming targeting AIAN and Hispanic/Latino youth and adolescents.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] (2019a) reports that substance use poses an increased risk of HIV. Among AIAN there is a high comorbidity of alcohol and other drug (AOD) use and HIV (Bertolli et al. 2004; Dombrowski et al. 2018). For example, investigating HIV risk behaviors, Bertolli and colleagues (Bertolli et al. 2004) found that the number of AIAN who met the criteria for alcohol dependence was higher than the rate of non-AIAN counterparts. Dombrowski et al. (2018) found that 86% of HIV patients attending a clinic reported active substance use. AIAN and Latino communities also have higher rates of interpersonal violence (Tehee and Esqueda 2008; Burnette 2015; Matamonasa-Bennett 2015), and AIAN children are exposed to more violence than any other ethnic group (U.S. Department of Justice 2014).

Historical trauma is described as one component of HIV risk in Indigenous communities attributable to disruptions in cultural practices, interpersonal relationships, and community cohesion (Evans-Campbell 2008; Walters et al. 2011). Historical trauma is defined as a collective and cumulative wounding as a result of targeted mass group assaults (e.g., boarding schools, forced removal, deportations, slavery). The trauma is both personal as well as collective, can be transmitted to future generations and can impact health and mental health outcomes (Heart and DeBruyn 1998; Evans-Campbell 2008; Sotero 2006). Disruptions of cultural traditions can impact Indigenous peoples’ ability to maintain traditional health practices for optimum health and well-being (Beltrán et al. 2018). These disruptions also impact relationships to self, family, community and the environment (Beltrán et al. 2018; Evans-Campbell 2008) and may lead to risky behaviors. Research suggests this combination of historical trauma, alcohol and substance abuse, and interpersonal violence creates an HIV “triangle of risk” (Walters et al. 2011).

Along with the existence of high rates of HIV, AOD, and other health risks related to historical trauma, research has identified numerous protective mechanisms for AIANs that may buffer the impact of trauma on HIV and AOD risk. Specifically, Indigenous health models, including the Indigenist Stress Coping Model (Walters and Simoni 2002) describe the role of culture and enculturation on buffering the impacts of historical trauma and social and environmental stressors on health outcomes. Cultural resilience factors that have shown promise in buffering the effects of traumatic stressors on health outcomes in AIAN communities include enculturation (Chae and Walters 2009; Novins et al. 2012; Walters et al. 2002), spirituality and traditional health practices (Novins et al. 2012; Walters et al. 2002), and feelings of connection to family, community, and the environment (Evans-Campbell 2008; Mohatt et al. 2011). Enculturation describes the degree to which individuals are integrated into their cultural traditions and encompasses the process of learning about and identifying with traditional language, customs and practices, spirituality, and nuances of cultural identity (Bals et al. 2011; Fleming and Ledogar 2008a). Specific enculturation factors including participating in cultural activities, developing a sense of ethnic pride, and learning native languages have also been described as cultural resilience factors (Bals et al. 2011; McIvor and Napoleon 2009). While findings have varied related to the degree to which enculturation is protective, many studies describe enculturation as a protective factor in reducing negative outcomes related to alcohol and substance use, academic success, suicidal ideation and mental health (Fleming and Ledogar 2008a). Enculturation is shown to mitigate negative impacts of life stressors on health outcomes (Walters and Simoni 2002) and has been empirically supported in studies examining the role of cultural identity development in improving educational health outcomes (Les Whitbeck et al. 2004; Zimmerman et al. 1996), and in reducing health and mental health burdens in Indigenous youth (Bals et al. 2011).

Specific to HIV prevention, Wyatt and colleagues (Wyatt et al. 2012) suggest that HIV prevention programs address cultural identities and beliefs, (rather than just targeting racial/ethnic groups) to address social and cultural factors that may contribute to risk behaviors (Wyatt et al. 2012). Programs that focus on culture-centered HIV interventions have yielded positive results (Walters et al. 2011). For example, Duran and colleagues (Duran et al. 2010) found significantly positive outcomes from culture-centered case management for HIV positive AIs in a rural southwest community. Additionally, other HIV prevention challenges within the AIAN and Latinx communities related to HIV status awareness, cultural stigma and confidentiality concerns, cultural diversity among the population, as well as limitations to data including racial misclassification (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] 2016), may be mitigated by a cultural-centered approach. Given these risks and the promise of cultural resilience factors, there is a need for HIV prevention research with holistic, culture-centered approaches and prevention programs that leverage community strengths (Walters and Simoni 2002; Evans-Campbell 2008; Walters et al. 2011).

Responding to the call for holistic culture-centered approaches to HIV prevention combined with the responsiveness of CBPR in Indigenous communities, our team worked in close relationship with community partners to develop the Indigenous Youth RiseUp! HIV Prevention Curriculum (IYR) with a focus on integrating cultural resilience and enculturation factors throughout the curriculum.

3. Methods

3.1. Culture-Centered Curriculum Development: A CBPR Approach

In line with a targeted, collaborative approach to CBPR within a specific geographic area (Weiner and McDonald 2013), the Indigenous Youth RiseUp! (IYR) curriculum was co-created by a team of Indigenous and Latinx university-based researchers, community leaders, and activists from five community organizations serving AI and/or Latinx communities. The objective was to design a community-based, culturally responsive prevention curriculum to address the risks related to HIV in the regional Indigenous community with a focus on adolescents. Specifically, the IYR curriculum was designed to increase enculturation and positive identity attitudes, two of the hypothesized buffers to health and mental health risks (Walters and Simoni 2002). The community members were actively involved throughout the duration of the project, from curriculum design, program implementation, evaluation, and dissemination.

Implemented by a team of Indigenous and Latinx researchers and facilitators in summer 2015, the program included educational modules on historical trauma, AOD abuse, and interpersonal violence, in addition to HIV and STI prevention to increase knowledge, decrease HIV risk behaviors, and reduce stigma among Indigenous youth. Our curriculum development team drew on multiple HIV prevention curricula utilized with Indigenous and Latinx youth (e.g., Cuídate, Circle of Life, Strengthening the Circle) to develop comprehensive modules that integrated traditional and contemporary Indigenous understandings of HIV risk (e.g., AOD use, interpersonal violence, historical trauma) and protective factors (traditional cultural practices, positive identity attitudes, and social cohesion). Creators of the curriculum acknowledge that with more than 370 million Indigenous people in the world, it is impossible to characterize a singular set of traditional beliefs. There are some, however, that are common to many Indigenous peoples throughout the world (e.g., respect for land, a holistic ecological orientation to balance in health and wellness). The research team and community partners worked to identify unifying beliefs, customs, and practices to design the modules, including content specific to characteristics of the urban Rocky Mountain region Indigenous communities. We also invited participants to relate and share content as understood through their respective tribal cultures.

The research team also partnered with local community experts to guide and implement aspects of the curriculum centering on healing from historical trauma from a regionally specific Indigenous lens. For example, we partnered with a local spoken-word and creative expression organization that had provided empowerment programming to youth in the targeted populations for over a decade. With their input, we integrated activities using their Indigenous model of poetry development into the curriculum. These local experts also further addressed potential issues of mistrust and misunderstanding among participants and researchers because they had long-standing relationships with the community (Mau et al. 2010).

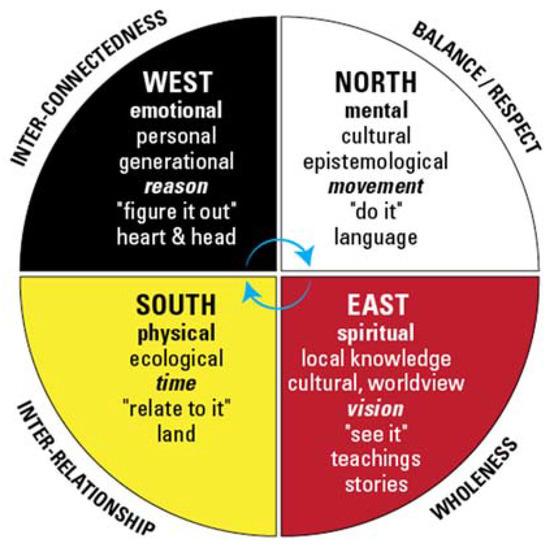

Similar to several other HIV prevention programs for Indigenous youth, the IYR curriculum used the medicine wheel as the framework for the curriculum design. The medicine wheel is increasingly used as an important framework for prevention and intervention with Indigenous communities and is the basis for numerous HIV and STI-prevention curricula with Indigenous youth (Kaufman et al. 2012; Red Circle Project 2016). Each quadrant of the medicine wheel represents different aspects of health and well-being (See Figure 1), and provides guidance about how to achieve balance. The quadrants mental (north), spiritual (east), physical (south), and emotional (west), each align with a primary aspect of the IYR curricula, and each lesson plan corresponded with the medicine wheel as a teaching tool. As the curriculum was implemented over four days, each day of the curriculum focused on one component of the medicine wheel. The curriculum development team created modules with corresponding educational activities that were associated with topics aligned with the respective medicine wheel direction. For example, day one was focused on the east direction and the central role of spirituality and its connection to worldviews and original lands for Indigenous peoples.

Figure 1.

Medicine Wheel (Bell 2013). This figure depicts an Anishinaabe Medicine Wheel and the corresponding teachings that align with the various sections of the wheel.

3.2. Curriculum Example: East/Spiritual

Specifically, on the east/spirituality day, the curriculum emphasized learning about the connections between health risk behaviors and historical trauma and healing, honoring ancestors and traditional knowledge, and understanding our bodies’ connection to land/place. After a morning blessing and contextualizing the curriculum within the medicine wheel framework, we provided an overview of the concept of historical trauma and healing by locating the groups’ ancestral origins or tribal territories on collective maps. Because the majority of our participants were Indigenous to North America (U.S. and Mexico), we used butcher paper to draw maps of these territories. We then asked participants to use colored stickers to locate their ancestral origins and/or tribal geographic locations on the map. Directed by the youth, we were asked to include additional maps of continental Africa and Europe so they could acknowledge the diverse aspects of their ancestral and cultural origins. After participants completed their maps, we gathered in a circle and facilitated a conversation about historical origins, migration histories, original land/territory, and consideration of both common and divergent historical experiences with colonization. Interestingly, despite diverse and intersectional origins, participants focused more on commonalities than differences. For example, the majority identified that they no longer live in their original tribal territories, an experience common to urban Indigenous communities. We discussed how displacement and relocation could be understood as an outcome associated with historically traumatic events (Evans-Campbell 2008; Walters et al. 2011).

Following the discussion, participants were asked to reflect on their own personal histories. They were given time to journal on important events within their ancestral and familial history and were encouraged to include both traumatic and healing events. After students had recorded their personal histories, the group gathered to create a singular historical trauma and healing timeline. Using sidewalk chalk, participants and facilitators wrote or drew their personal histories onto a singular (non-linear) timeline on a large outdoor patio, doing so in silence. Once the group timeline was complete, participants and facilitators stood in a circle and one-by-one described what they saw represented. Once again, participants reflected on the commonalities across groups, including: Presence of similar massive traumatic events (e.g., relocation, forced migration, boarding schools, police brutality) as well as collective healing responses and cultural resilience factors (e.g., tribal creation stories, cultural dance, songs, language, and educational accomplishments). We discussed how cultural resilience factors such as traditional cultural practices, educational attainment, and tribally specific beliefs also function as means to interrupt the intergenerational transmission of trauma.

By acknowledging the profuse nature of historically traumatic events for Indigenous peoples across tribal origins in this activity, we illuminated commonalities, made room for a focus on the strengths and creativity of Indigenous communities, and connected these strengths back to Indigenous cultural values and practices; factors associated with enculturation. This empowered participants to more clearly articulate which aspects of their struggle and their strength emanated from their ancestors, community, family, and personal cultural identity. All of the educational modules used similar strategies, integrating cultural values and practices within the HIV prevention curriculum. Throughout the curriculum, as we explored HIV health risk topics, we utilized Indigenous talk story pedagogy (Foy 2009), offered smudge to participants with medicinal plants common to the Indigenous people of the region (e.g., sweetgrass, sage, cedar, and copal), and referred back to the values described in the medicine wheel as they connected to each educational component.

4. Data Collection

4.1. Recruitment

Using a purposive sampling strategy, community partners recruited 25 Indigenous identifying youth from within their community programs and services, targeting youth between the ages of 14–25. Participants in this age bracket were recruited due to the disproportionate risk for HIV/AIDS among ethnic minorities in the age group (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] 2018). Eligibility criteria required that youth be between the ages of 14–25, have the ability to read, understand, and speak English, and be available for the full duration of the curriculum (four 8 hour days over two weekends in a summer month). Members of the research team screened participants either in person or via phone. When eligible, baseline demographic information and contact information were collected. Informed consent and minor assent was collected by research staff either at community partner organizations, participant homes, or on-site on the first day of the curriculum. All informed consent and assent documents were available in both English and Spanish to make the project information accessible to Spanish-speaking youth and families, and bilingual research staff collected informed consent for youth from Spanish-speaking parents.

4.2. Participant Demographics

Of the 25 youth that enrolled in IYR, 23 completed the workshop, pre-curriculum surveys, and follow-up interviews. Ages ranged from 14–22, with the majority of participants being under 18 (n = 15) and the remaining 8 being between 18–22 years old. The sample was split with 11 participants identifying as male and 12 identifying as female. Additionally, 13% (n = 3) identified as Two-Spirit, and an additional 8% (n = 2) identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender or queer/questioning (LGBTQ). Race/ethnic identity descriptions represented in the pre-curriculum demographic baseline included: Latino, Mexican, Native American, African American, and mixed-race. Tribes represented in the sample at pre-protocol demographic baseline included (alone or in combination): Chippewa, Navajo/Dine, Hopi, Sioux, Oglala Lakota, Nez Perce, Choctaw, and Southern Ute.

4.3. Research Design

The project research plan included three components. The first was completion of a series of several demographic questions for each eligible participant, which gave us a baseline record of tribal and racial/ethnic identity, age, and gender. The second component of the research was a pre- and post-intervention survey assessing knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors (KABB) that included items related to HIV, STIs, sexual and romantic relationships, as well as gender identity and sexual orientation. The third component was a post-curriculum in-depth interview, which asked participants to reflect on the educational topics and their experiences in the curriculum. The findings reported in this paper focus on salient themes related to cultural identity and enculturation factors that emerged from the post-curriculum interviews. The post-curriculum in-depth individual interviews were conducted one- to two-weeks post-curriculum. The semi-structured qualitative protocol included questions related to each aspect of the curriculum including: Cultural identity, perceived relationships with self, partners, and/or community; perceptions of physical body and sexuality; emotional health and sexuality; mental health and sexual health decisions; as well as overall feedback about the program.

5. Data Analysis

All interviews were audio recorded and professionally transcribed. After interviews were transcribed, they were cleaned and de-identified by members of the research team. An initial codebook was developed using questions from the interview guide as organizing themes. Using Dedoose analytic software, we conducted a broad thematic analysis to identify overarching themes (e.g., cultural identity description, cultural pride). Initial coding reduced the data into distinct components for closer examination, allowing for more nuanced comparison and contrast (Saldaña 2015). Our in-depth thematic analysis revealed sub-themes with more intricate meanings that illuminated complexities in participant experiences.

6. Results

In this paper, we highlight three salient themes related to enculturation factors and identity: Developing a sense of cultural pride, honoring ancestors through traditional cultural practices, and acknowledging resistance and resilience. Findings presented below use pseudonyms to protect confidentiality, and a designation of “minor” is used for participants under the age of 18.

6.1. “I Just Feel Proud that I’m Native”: Developing a Sense of Cultural Pride

An important aspect of enculturation is the process in which youth learn about and identify with their traditional Indigenous culture and consequently develop a sense of cultural pride (Bals et al. 2011). Consistent with literature that defines cultural or ethnic pride as an enculturation factor (Bals et al. 2011), participants described numerous processes of learning about their Indigenous heritage that were fostered, facilitated, and supported by the curriculum. For many youth, these processes included becoming more aware of cultural identity. Twenty youth described various processes of learning about their Indigenous cultural heritage as part of how they define pride in their culture. Marco (minor) described the value of knowing his cultural past, including the impact of historical trauma and a desire to educate others on that aspect of history.

Caring about my past, not my past but a cultural past… We’ve been through so much trauma…we’re different and we’re treated differently…we’re singled out because we’re a different color or we come from different places…or what happened in the past is passed on to us…I just feel proud that I’m Native American … So that makes me want to tell them what we’ve been through.(Marco, minor)

Seventeen youth described an absence of fear and shame as part of cultural pride, and one quarter of participants reported that self-identifying as Indigenous with no shame was an important part of their Indigenous identity.

When I talk about pride, I think about no shame, not shaming it any way, and making sure that every piece of our culture, every aspect of it is made beautiful and made sacred … because it hasn’t been for so long.(Belen)

Gabriel (minor) described an absence of fear as important in claiming his own sense of cultural pride. It is “not being scared of where you come from and what your cultural beliefs are.” For Amara, embracing cultural practices, even if they are outside of the dominant norm is one way of rejecting shame. To her, cultural pride is “just trying to embrace those things and trying to embrace even those different cultural holidays, cultural practices, that aren’t the norm in the United States.”

Additionally, being surrounded by other Indigenous people (facilitators and youth) had positive impacts on the level of comfort and connection described. Participating in IYR allowed participants to connect to the idea of what being “Indigenous” is in a safe collective space that they described as not existing in spaces like schools or other youth programs. Marisa explains:

Being in a space of people who identify as Indigenous, having their identity connected to that word, that identity alone, just Indigenous, it’s not a way that we are able to classify ourselves if we’re like outside of a reservation or unless we’re like with our families. Otherwise, there’s not spaces in schools, in youth programs … [there are] very few that are specifically for Indigenous or mixed Indigenous youth.(Marisa)

Making connections to others with similar experiences within the IYR curriculum further normalized their experiences and expressions of cultural traditions. As Belen describes:

Just being around other Indigenous youth, being able to talk about things that I haven’t been able to talk about for a long time since I moved from [another state], about pow-wows and dancing and that being so normal in our communities. And you notice when you’re not around that or when you’re not exposed to that as often, ’cause you just don’t talk about it; and then you’re in that space and other youth are talking about it in this way that it’s just like, “Oh, yeah, I’m going to this and that,” and other people are like, “Oh, my God, I wanted to go to that so bad.” And it’s beautiful just to hear those conversations happen so naturally.(Belen)

The development of cultural pride is an example of an enculturation factor that has been connected to reducing poor health and mental health outcomes, and for the youth participating in IYR, it is also connected to honoring ancestors through embracing and engaging with traditional cultural practices.

6.2. “To Live the Way that Our Ancestors Lived”: Honoring Our Ancestors through Traditional Cultural Practices

Ten of the participants described traditional cultural practices and language as part of how they define cultural pride. Dancing, participating in pow-wows, wearing Native/traditional clothes, and eating cultural foods were all described as important elements of their Indigenous identity expression. While these specific cultural activities were not all part of the experiential activities within the curriculum, the facilitators created a space where these activities surfaced and were named as important aspects of cultural identity. As such, the curriculum created community and fostered connections between participants, facilitators, and volunteers through their cultural practices. Several youth described the process of naming and connecting to culture and traditions as a positive manner in which to acknowledge their ancestors. Naran (minor) comments, “Having a culture, having tradition, having ceremonies and rituals you can do and you can practice… You’re like directly practicing history. You’re doing something that your ancestors did; so, it’s really cool.” Belen continues this thread through describing the act of cultivating and preparing food as an important part of honoring ancestors. She states “…The food that I cook and grow and eat. I try to keep it like the food that was traditional for our ancestors” (Belen).

Honoring ancestors through cultural practices was also described as part of the trajectory of passing knowledge on to future generations as a means of maintaining connections to those practices. Sergio describes a responsibility to maintain ancestral ways as a path toward mentoring relatives, siblings, and younger community members with shared identities. Sergio says:

Just doing what my Grandma told me, like trying to keep some of the ways. Going to pow-wows, trying to get really just [healthy] food, to live the way that our ancestors used to live and trying to be a mentor to my younger ones.(Sergio, minor)

Hector (minor) described a process of “staying in touch” with his ancestors as an important part of finding pride and comfort in cultural identity. He explains:

Just be me, and stay in touch with [traditional cultural] practices. Some practices will be like prayers and sweat lodges; and it could also be like walking, thinking, and taking a moment to step aside and remember where you came from. Just go for a walk and thank your ancestors for where you are now—let them know you’re in good hands.(Hector, minor)

Consistent with literature describing positive impacts of integrating cultural practices to HIV prevention and intervention approaches (Duran et al. 2010) as well as literature describing the protective role of enculturation in health outcomes (LaFromboise et al. 2006; Stone et al. 2006; Whitbeck et al. 2004), IYR engaged cultural practices within the curriculum to simultaneously increase positive identity attitudes, enculturation, and HIV health knowledge. Part of this involved contextualizing current health outcomes as connected to historically traumatic events while also highlighting the strength and persistence of Indigenous communities not only to survive but also to thrive.

6.3. “We’re Still Here”: Acknowledging Resilience and Resistance

One third of the youth described the strength and resilience of their people(s) as being a source of pride for them. Fleming and Ledogar (2008b) define resilience as “positive adaptation despite adversity” (p.1). Along with cultural practices, knowledge of historical injustices and the impacts on their communities today were embedded in experiential and dialogic activities throughout the IYR curriculum and were reinforced by several youth in the follow-up interviews. Jaime connected his sense of cultural pride not only to understanding his culture but also to understanding the complex and difficult historical legacy of his ancestors. For Jaime, this understanding of his ancestral legacy is part of what gives him strength in the here and now to face his own struggles:

Cultural pride means, first of all, knowing your culture—understanding it and knowing where you came from—and then being proud of the struggles that your ancestors had to go through; using that strength and knowledge to overcome obstacles that you have to go through personally.(Jaime)

Jaime continues describing his ancestors’ resistance and survival despite efforts of physical and cultural destruction:

We’re still here. We went through a genocide. The mission was to have us completely wiped out, and that’s not the case; so just being able to survive genocide, that shows that our people are incredibly strong.(Jaime)

Belen also describes resistance despite multiple colonial efforts to control and destroy while highlighting intersectional aspects of her cultural and gender identity. She says:

I think that I’m most proud of the resistance of my people and my culture… it’s been tried to be wiped out for so long and so hard, in both Mexico and up here, like by different colonizers and everything. And as two-spirit young people, we literally have been to tried to [be] wipe[d] out.(Belen)

This focus on the resilience and resistance of their respective Indigenous communities illustrates how youth who participated in IYR see their ancestral and cultural lineage as a strength and resource.

6.4. Additional Findings: Member-Checking and Community Directives

When we began this project, community partners asked to build in a plan to share findings and conduct member-checking through providing a research capacity building training upon completion of curriculum implementation and initial data analysis. In accordance with the bidirectional information sharing within CBPR, the community requested that we design a workshop for collaborators and community members that highlighted decolonial processes in research using the findings from the study as the foundation for the training. As directed by our community partners, all participating organizations, stakeholders, youth, and interested community members were invited to attend. It is important to note that through this member-checking process, when we took our initial data report back to our community stakeholders they were encouraged by the positive changes resulting from the KABB survey (published in a community report in 2017), but they were most enthusiastic about the findings related to enculturation factors and changes in cultural identity descriptions. In fact, during the workshop/share-back, one of our community partners jubilantly yelled “la cultura cura” (culture cures)! As such, the presentation of observations related to the shifts in identity descriptions presented below is driven by the community prioritization to document the value of the role of cultural identity in prevention, intervention, and healing.

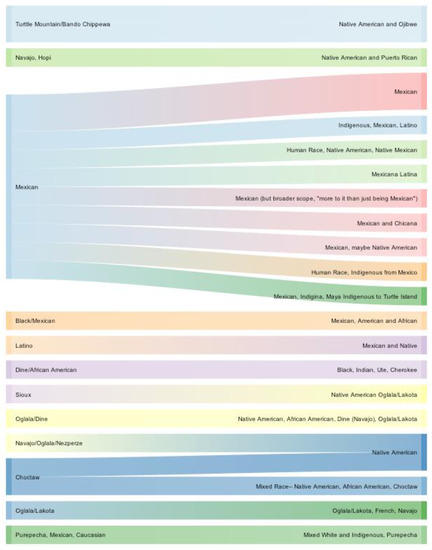

6.5. Emerging Identities

In our exploration of cultural identity development, we noticed salient shifts in tribal and race/ethnic identity descriptions from the demographic form to answers in the follow-up interview. Changes in identity descriptions were most striking in individuals who described themselves as “Mexican” or “Latino” prior to participating in the curriculum. Of the 10 individuals who identified as “Mexican” on the eligibility form, 7 reported different race/ethnic identity descriptions (e.g., Indigenous, Mexican and Latino, Native American, Native Mexican, Indigenous from Mexico) in the post-workshop follow-up interview. One youth, Manuel, described his emerging identity as directly related to participating in IYR, stating, “Well, I still identify as Mexican, because that’s how I’ve always identified, but these workshops have made me look at [the] broader scope of what that means. Like there’s more to it … than just being Mexican.” Similarly, an individual who identified as “Latino” prior to the workshop, identified as “Mexican and Native” in the follow-up interview.

Several participants reported more specificity of their tribal heritage or included more aspects of their racial/ethnic identity. For example, on the demographic form, one participant identified as “Sioux,” a description of a larger ethnic group representing several tribal bands in the plains region of the United States. In the follow-up interview, the same participant identified as “Oglala Lakota”, more specific to their tribal band. While four of the participants’ identity descriptions became more broad (e.g., from Choctaw to Native American), the remaining nineteen participants either described more specificity to their tribal heritage or to a more comprehensive description of their intersectional identities (see Figure 2). While not conclusive, these changes point to a possible increase in understanding of Indigenous cultural identity after participating in the IYR curriculum and illuminate opportunities for future exploration and evaluation of these aspects of identity shifts for youth participating in a culture-centered HIV prevention curriculum.

Figure 2.

Changes in Tribal and Racial/Ethnic Identity. This is a data visualization graphic depicting changes in tribal and racial/ethnic identity from the baseline demographic survey to the post-intervention interviews. The categories on the left are the data derived from the baseline demographic survey. The categories on the right are the post-intervention identity descriptions gathered in the post-intervention interviews. The thicker lines depict multiple participants and displays the shifting racial/ethnic and tribal identification of participants pre- and post-intervention.

7. Discussion

In their review of resilience literature, Fleming and Ledogar (2008b) describe community level resilience resources, including school experiences (peer support, positive teacher influences, academic success), community support (belief in individual, non-punitive relationships, support for belief in values of society), and cultural resources (traditional spirituality, language, activities, and healing). As illustrated by the themes described above, IYR fostered community level resilience resources and leveraged enculturation factors by centering cultural values, practices, and activities throughout the educational components of the curriculum. While we cannot make direct correlations to reduced HIV risk behaviors within this analysis, these themes align with research that has found positive health and mental health outcomes associated with enculturation and cultural resilience.

CBPR approaches have been used to develop interventions that are infused with Indigenous epistemology and culture, which is recommended when engaging Indigenous communities in research (Dickerson et al. 2018). Centering culture in intervention work requires projects that are “based on Indigenous history, language, values, and healing traditions as ways for people to heal from historical traumas” (Dickerson et al. 2018, p. 2). The principles of CBPR can be expanded to recognize historical trauma and other inequities that can impact partnerships and mutuality between community and university groups (Wallerstein and Duran 2006). This research team made efforts to mitigate these potential barriers in a number of ways. First, by engaging with an Indigenous/Latinx/Persons of Color (POC)1 research team (throughout all phases of the research), the team attempted to minimize cultural barriers, racial/ethnic and cultural microaggressions, and to increase trust among and between community and university partners. That said, there were efforts made to acknowledge varying levels of participation and engagement throughout the project so as to mitigate power imbalances and to honor shifting capacities for contribution based on interest, time demands, and expertise (Israel et al. 2005; Wallerstein and Duran 2006). Additionally, per community directives, in combination with data-sharing, the research team facilitated community training about research ethics and problematics when working in Indigenous communities to highlight the necessary self-reflection, attention to power, and acknowledgement of historical and on-going harm that has been committed in the name of research when attempting university-community partnerships.

Successful approaches to CBPR contribute something valuable to the community (Weiner and McDonald 2013), and as such, the community partners drove the focus of the analysis, as well as the research dissemination plan. Through this targeted CBPR approach, the university and community partners were able to create shared goals contributing to their mutual interests (Weiner and McDonald 2013). Challenges for CBPR practitioners working in Indigenous communities have included needing to be flexible about research methodologies and protocols (Holkup et al. 2004). Specifically, adjusting protocols based on the community needs and interests, adding time for self-reflection in research team meetings to center relationships and mutual learning, and actively discussing how to honor the needs of the participants (Holkup et al. 2004).

The CBPR approach used with the IYR project provided a strong model for this level of community engagement, particularly when the research team realized that there were aspects of the research more interesting and relevant to the community than was originally designed. Specifically, the identity-level shifts that the research team discovered in the comparison between the pre- curriculum demographic questionnaire and post-curriculum interviews resonated deeply with community partners, and felt like a validation of what they instinctively and anecdotally already knew; that programs rooted in Indigenous culture have the power to strengthen and deepen participants’ identification with that culture. As an approach that values community needs, relationships, and responsiveness above program evaluation and/or fidelity of implementation (Dignan et al. 2014), the CBPR approach allowed for the research team to be responsive to these interests and to pursue the questions of identity and enculturation as we continued to explore the data.

8. Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. First, because the sampling strategy was purposive and many of the youth recruited were connected to partner organizations through their respective youth programming, the participants may have already had a robust connection to enculturation factors in their own lives, and their descriptions may not be representative of a broader sample of Indigenous youth who are not actively participating in organizational programming. This may have also contributed to the high retention rate of participants in the study. Second, the interview responses were overwhelmingly positive and, given that members of the research team who were also part of facilitating the curriculum conducted the interviews, there is also the possibility that social desirability bias is reflected in participant interviews. Third, there are methodological challenges to conducting analyses with two distinct forms of data. Responses to the tribal and race/ethnic identifications on the baseline demographic questionnaire most certainly cannot capture the nuances of identity. Comparing these responses to more nuanced qualitative descriptions detailed in the in-depth interviews is not an optimal measure of pre- to post-curriculum change. Nevertheless, this was an encouraging observation to the community and presenting this here reflects the relational as well as the adaptive and iterative process embedded within the CBPR approach. Future iterations of this curriculum or similar projects should build in pre- and post-intervention identity measures that can more accurately capture changes to descriptions. Finally, the project has not been successfully funded for repeat implementation. Due to these funding limitations, the curriculum has not been manualized for further evaluation and dissemination. Optimally, manualization of the curriculum and multiple implementations with a randomized control trial design would yield more conclusive evidence on the effectiveness of the curriculum. Culturally supported interventions are often practiced and implemented in the community but are not systematically evaluated or recognized for their impacts (Wallerstein and Duran 2006). In many Indigenous communities, regular efforts are being made toward healing from historical trauma (through cultural events, arts, and/or healing ceremonies; Chino and Debruyn 2006; O’Keefe et al. 2019), and additional efforts to support, document, and measure these practices would also be an important area for continued work.

9. Conclusions

The IYR curriculum was designed to address the multiple prongs of HIV risk as described by the HIV “triangle of risk” (Walters et al. 2011). Specifically, we sought to increase enculturation and identity attitudes, two of the hypothesized “buffers” to health and mental health risk outcomes (Walters and Simoni 2002) by incorporating cultural activities and lessons that drew connections between historical and contemporary struggles and strengths within Indigenous communities to health risk and protective behaviors. Analysis of post-curriculum in-depth interviews shows that participation in IYR is associated with enculturation factors including developing a sense of cultural pride, honoring of ancestors through participating in traditional cultural activities, and acknowledging the resilience and resistance that is endemic to Indigenous communities despite experiences of historical trauma.

Additionally, as prioritized by community partners, changes in identity descriptions for youth that participated in the IYR curriculum underscore the potential of centering culture in an HIV prevention curriculum for Indigenous youth. While the findings presented in this paper do not demonstrate changes to HIV risk behaviors, they align with established empirical evidence linking development of positive cultural identity and enculturation factors to reduction in risky health outcomes and illuminate opportunities for innovations in HIV and health prevention curricula broadly. Further implementation and evaluation of this curriculum is necessary to measure impacts of cultural resilience and enculturation factors on HIV risk behaviors.

Author Contributions

R.B. and X.A. conceived and designed the curriculum and evaluation of the curriculum along with the IYR team; R.B. and X.A. implemented the curriculum and conducted evaluation surveys and interviews along with other members of the IYR research and community team; A.R.G.A. led the data analysis represented in this paper, which was also supported by R.B.; R.B. and A.R.G.A. led the substantive development of this paper; L.C., X.A., and A.Z.D. assisted in paper development, writing the body of the paper, and provided editing and formatting support. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abma, Tineke, Sarah Banks, Tina Cook, Sónia Dias, Wendy Madsen, Jane Springett, and Michael T. Wright. 2019. Participatory Research for Health and Social Well-Being. Springer. Available online: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007%2F978-3-319-93191-3 (accessed on 28 January 2020).

- Bals, Margrethe, Anne Lene Turi, Ingunn Skre, and Siv Kvernmo. 2011. The relationship between internalizing and externalizing symptoms and cultural resilience factors in Indigenous Sami youth from Arctic Norway. International Journal of Circumpolar Health 70: 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, Nicole. 2013. Just do it: Anishinaabe Culture-based education. Canadian Journal of Native Education 36: 36–58. [Google Scholar]

- Beltran, Ramona, Katie Schultz, Angela Fernandez, Karina Walters, Bonnie Duran, and Tessa Evans-Campbell. 2018. From ambivalence to revitalization: Negotiating cardiovascular health behaviors related to environmental and historical trauma in a Northwest American Indian community. Journal of American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research 25: 103–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertolli, Jeanne, A. D. McNaghten, Michael Campsmith, Lisa M. Lee, Richard Leman, Ralph T. Bryan, and James W. Buehler. 2004. Surveillance systems monitoring HIV/AIDS and HIV risk behaviors among American Indians and Alaska natives. AIDS Education and Prevention 16: 218–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brockie, Teresa N., Gail Dana-Sacco, Miriam Magaña Lopez, and Lawrence Wetsit. 2017. Essentials of research engagement with Native American Tribes: Data collection reflections of a tribal research team. Progressive Community Health Partnerships 11: 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, Jessica G., Sally Hess, Kamden Hoffmann, Lisa Guizzetti, Ellyn Loy, Andrea Gielen, Maryanne Bailey, Adrienne Walnoha, Genevieve Barbee, and Michael Yonas. 2013. Translating community-based participatory research (CBPR) principles into practice: Building a research agenda to reduce intimate partner violence. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, And Action 7: 115–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnette, Catherine E. 2015. Disentangling indigenous women’s experiences with intimate partner violence in the United States. Critical Social Work 16: 2–20. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]. 2016. HIV/AIDS among Latinos, American Indians and Alaska Natives. CDC HIV/AIDS; [Fact sheet]. Revised October, 2015. Available online: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/cdc_36608_DS1 (accessed on 1 November 2019).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]. 2018. National Gay Men’s HIV/AIDS Awareness Day—September 27, 2018. In Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report; 67, p. 1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]. 2019a. HIV and substance use in the United States. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/substanceuse.html (accessed on 1 November 2019).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]. 2019b. HIV Surveillance Report. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/cdc-hiv-surveillance-infographic.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2019).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]. 2019c. HIV Surveillance Report, 2018 (Preliminary). Atlanta, Georgia U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. vol. 30. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2018-vol-30.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2019).

- Chae, David H., and Karina L. Walters. 2009. Racial discrimination and racial identity attitudes in relation to self-rated health and physical pain and impairment among two-spirit American Indians/Alaska Natives. American Journal of Public Health 99: S144–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chino, Michelle, and Lemyra Debruyn. 2006. Building true capacity: Indigenous models for indigenous communities. American Journal of Public Health 96: 596–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickerson, Daniel, Julie A. Baldwin, Annie Belcourt, Lorenda Belone, Joel Gittelsohn, Joseph Keawe’aimoku Kaholokula, John Lowe, Christi A. Patten, and Nina Wallerstein. 2018. Encompassing cultural contexts within scientific research methodologies in the development of health promotion interventions. Prevention Science 21: 1–10. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-018-0926-1 (accessed on 15 November 2019).

- Dignan, Mark B., Kate Jones, Linda Burhansstipanov, and Arthur M. Michalek. 2014. Evaluation lessons learned from implementing CBPR in Native American communities. Journal of Cancer Education 29: 412–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dombrowski, Julia C., Meena Ramchandani, Shireesha Dhanireddy, Robert D. Harrington, Allison Moore, and Matthew R. Golden. 2018. The Max clinic: medical care designed to engage the hardest-to-reach persons living with HIV in Seattle and King County, Washington. AIDS Patient Care and STDs 32: 149–56. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Duran, Bonnie, Melvin Harrison, Maynard Shurley, Kevin Foley, Priscilla Morris, Lynn Davidson-Stroh, Jonathan Iralu, Yizhou Jiang, and Michele Peake Andrasik. 2010. Tribally-Driven Hiv/Aids Health Services Partnerships: Evidencebased Meets Culture-Centered Interventions. Journal of HIV/AIDS & Social Services 9: 110–29. [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Campbell, T. 2008. Historical trauma in American Indian/Alaska Native communities: A multilevel framework for exploring impacts on individuals, families, and communities. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 23: 316–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleming, John, and Robert J. Ledogar. 2008a. Resilience and indigenous spirituality: A literature review. Pimatisiwin 6: 47. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, John, and Robert J. Ledogar. 2008b. Resilience, an evolving concept: A review of literature relevant to Aboriginal research. Pimatisiwin 6: 7. [Google Scholar]

- Foy, Jackie. 2009. Incorporating talk story into the classroom. First Nations Perspectives 2: 25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Heart, Brave, and Lemyra M. DeBruyn. 1998. The American Indian Holocaust: Healing historical unresolved grief. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research 8: 56–78. [Google Scholar]

- Holkup, Patricia A., Toni Tripp-Reimer, Emily Matt Salois, and Clarann Weinert. 2004. Community-based participatory research: An approach to intervention research with Native American community. Advances in Nursing Science 27: 162–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israel, Barbara A., Amy J. Schulz, Edith A. Parker, and Adam B. Becker. 1998. Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health 19: 173–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israel, Barbara A., Edith A. Parker, Zachary Rowe, Alicia Salvatore, Meredith Minkler, Jesús López, Arlene Butz, Adrian Mosley, Lucretia Coates, George Lambert, and et al. 2005. Community-based participatory research: Lessons learned from the Centers for Children’s Environmental Health and Disease Prevention Research. Environmental Health Perspectives 113: 1463–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, Carol E., Anne Litchfield, Edwin Schupman, and Christina M. Mitchell. 2012. Circle of Life HIV/AIDS-prevention intervention for American Indian and Alaska Native youth. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research: The Journal of the National Center 19: 140–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaFromboise, Teresa D., Dan R. Hoyt, Lisa Oliver, and Les B. Whitbeck. 2006. Family, community, and school influence in resilience among American Indian adolescents in the upper Midwest. Journal of Community Psychology 34: 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Les Whitbeck, B., Xiaojin Chen, Dan R. Hoyt, and Gary W. Adams. 2004. Discrimination, historical loss and enculturation: culturally specific risk and resiliency factors for alcohol abuse among American Indians. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 65: 409–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matamonasa-Bennett, A. 2015. “A disease of the outside people” Native American men’s perceptions of intimate partner violence. Psychology of Women Quarterly 39: 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mau, Marjorie K., Joseph Keawe‘aimoku Kaholokula, Margaret R. West, Anne Leake, James T. Efird, Charles Rose, Donna-Marie Palakiko, Sheryl Yoshimura, Puni B. Kekauoha, and Henry Gomes. 2010. Translating diabetes prevention into Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander communities: The PILI Ohana Pilot Project. Progressive Community Health Partnerships 4: 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIvor, Onowa, and Art Napoleon. 2009. Language and culture as protective factors for at-risk communities. Journal of Aboriginal Health 5: 6–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohatt, Nathaniel V., Carlotta Ching Ting Fok, Rebekah Burket, David Henry, and James Allen. 2011. Assessment of awareness of connectedness as a culturally-based protective factor for Alaska native youth. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 17: 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novins, Douglas K., Misty L. Boyd, Devan T. Brotherton, Alexandra Fickenscher, Laurie Moore, and Paul Spicer. 2012. Walking on: Celebrating the journeys of Native American adolescents with substance use problems on the winding road to healing. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 44: 153–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keefe, Victoria M., Mary F. Cwik, Emily E. Haroz, and Allison Barlow. 2019. Increasing culturally responsive care and mental health equity with Indigenous community mental health workers. Psychological Services. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/ser0000358 (accessed on 1 November 2019).

- Purdy, B. 2013. “Our women and girls are dying”: HIV/AIDS in Indigenous communities. In First Peoples Worldwide. West Vancouver: The Red Road HIV/AIDS Network. Available online: http://firstpeoples.org/wp/tag/indigenous-health/ (accessed on 4 October 2013).

- Red Circle Project. 2016. Strengthening Communities. Available online: http://redcircleproject.org/ (accessed on 31 October 2019).

- Saldaña, J. 2015. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. Los Angeles, London, New Deli, Singapore and Washington, DC: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Sotero, M. 2006. A conceptual model of historical trauma: Implications for public health practice and research. Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice 1: 93–108. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, Rosalie A. Torres, Les B. Whitbeck, Xiaojin Chen, Kurt Johnson, and Debbie M. Olson. 2006. Traditional practices, traditional spirituality, and alcohol cessation among American Indians. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 67: 236–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehee, Melissa, and Cynthia Willis Esqueda. 2008. American Indian and European American women’s perceptions of domestic violence. Journal of Family Violence 23: 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Justice. 2014. Attorney General’s Advisory Committee on American Indian and Alaska Native Children Exposed to Violence: Ending Violence So Children Can Thrive; (Report 11-2014). Available online: https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/defendingchildhood/pages/attachments/2015/03/23/ending_violence_so_children_can_thrive.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2019).

- Walker, Frances J., Jane M. Kelly, Mona Doshani, Neeraja Saduvala, and Joseph Prejean. 2015. Epidemiology of HIV among American Indians and Alaska Natives–United States, 2008–2011. Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice 8: 7. [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein, Nina B., and Bonnie Duran. 2006. Using Community-Based Participatory Research to address health disparities. Health Promotion Practice 7: 312–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallerstein, Nina B., and Bonnie Duran. 2017. The theoretical, historical and practice roots of CBPR. In Community Based Participatory Research for Health: Advancing Social and Health Equity, 3rd ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, pp. 17–29. [Google Scholar]

- Walters, Karina L., and Jane M. Simoni. 2002. Reconceptualizing Native women’s health: An “indigenist” stress-coping model. American Journal of Public Health 92: 520–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, Karina L., Jane M. Simoni, and Teresa Evans-Campbell. 2002. Substance abuse among American Indians and Alaska Natives: Incorporating culture in an “indigenist” stress-coping model. In Public Health Reports. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publishing, vol. 117, pp. 5104–17. [Google Scholar]

- Walters, Karina L., Ramona Beltran, Tessa Evans-Campbell, and Jane M. Simoni. 2011. Keeping our hearts from touching the ground: HIV/AIDS in American Indian and Alaska Native Women. Women’s Health Issues 21: S26–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, Janet, and J. A. McDonald. 2013. Three models of Community-Based Participatory Research. Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics 18: 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt, Gail E., John K. Williams, Arpana Gupta, and Dominique Malebranche. 2012. Are cultural values and beliefs included in U.S. based HIV interventions? Preventive Medicine 55: 362–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, Marc A., Jesus Ramirez-Valles, Kathleen M. Washienko, Benjamin Walter, and Sandra Dyer. 1996. The development of a measure of enculturation for Native American youth. American Journal of Community Psychology 24: 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | The research team during development and implementation was all Indigenous and/or Latinx. Later in the project, new research team members identifying as non-Indigenous people of color joined the analysis and dissemination. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).