Group and Child–Family Migration from Central America to the United States: Forced Child–Family Separation, Reunification, and Pseudo Adoption in the Era of Globalization

Abstract

1. Background

2. Materials and Methods

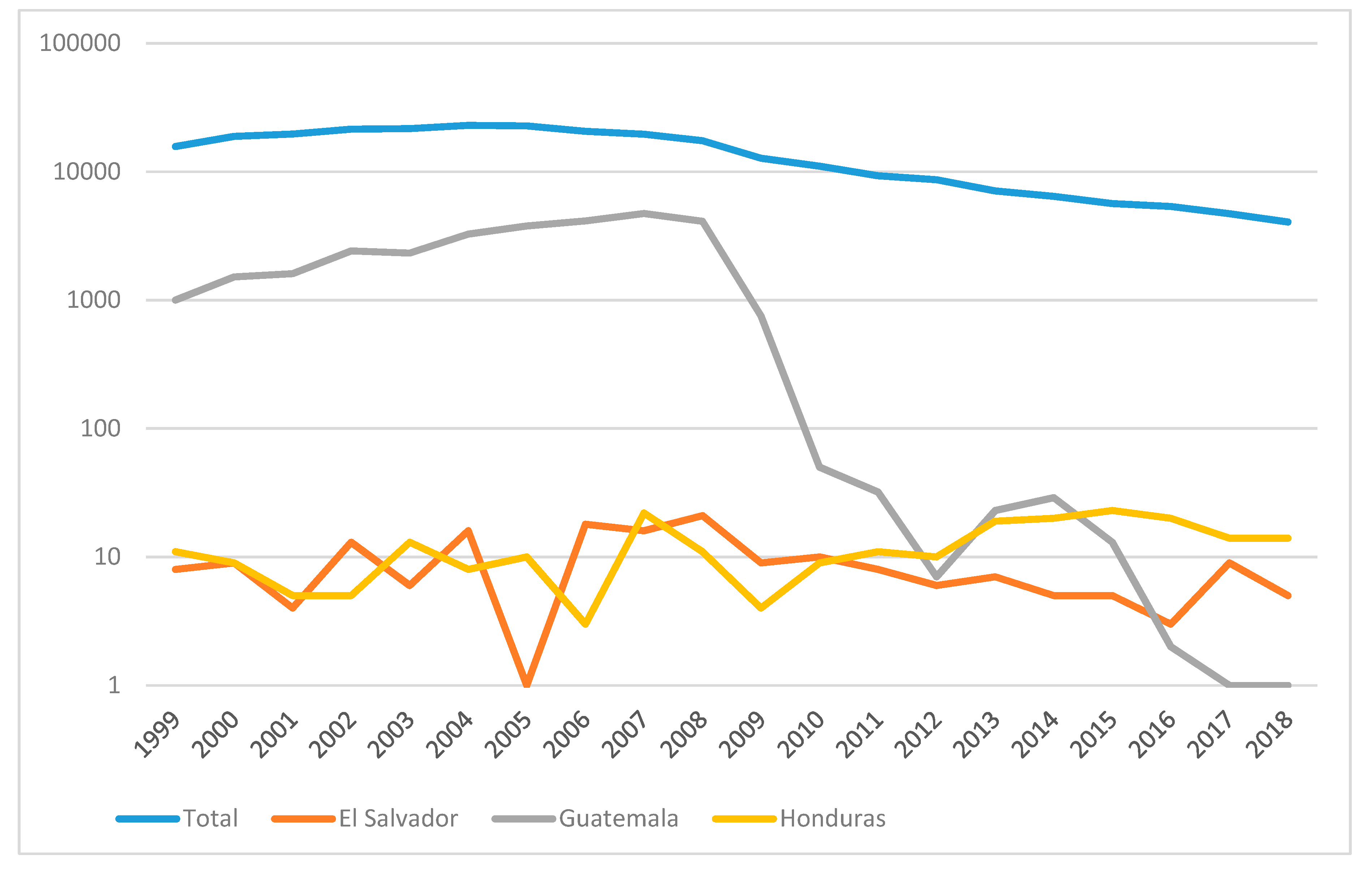

3. Historical Evolution of Intercountry Adoption from Latin America and Child Protection in Central American Northern Triangle Countries: Country Case Studies

3.1. The Case of El Salvador

3.2. The Case of Guatemala

3.3. The Case of Honduras

4. From Apprehension to Separation to Institutionalization and De Facto Adoption: Individual Case Studies

4.1. Forced Child–Family Separation Resulting from U.S. Immigration Policies

4.2. From Apprehension to Separation to Institutionalization and De Facto Adoption: Individual Case Examples

- (1)

- Separation by death: the death of toddlers, young children, youth, and adolescents during or soon after U.S. government custody;

- (2)

- Prolonged separation: the return of children to biological parents and relatives after extended or indefinite separation;

- (3)

- No reunification insight: families divided before, during, and after the zero-tolerance policy, with children remaining institutionalized as they are not eligible for adoption; and

- (4)

- Definite or temporary loss of parental rights: the loss of parental rights after detention of biological parents due to criminal charges (crossing without CBP inspection), the use of fraudulent documentation at work, or cases of domestic violence (those reported and investigated but not necessarily substantiated).

4.2.1. Cases of Separation by Death

4.2.2. Cases of Prolonged Separation

4.2.3. Cases of No Reunification in Sight

4.2.4. Cases of Definitive or Temporary Loss of Parental Rights

5. Discussion

5.1. Patterns, Policy Options, and Administrative Hurdles for Children in Current U.S. Systems

5.2. Implications for the Protection, Development, and Well-Being of Child Migrants in the U.S.

5.3. A Child Rights-Based Approach to the Care of Migrant Children in the U.S.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- ACLU. 2018a. ACLU to court: Order the Government to Reunite the Families. Available online: https://www.aclu.org/blog/immigrants-rights/immigrants-rights-and-detention/aclu-court-order-government-reunite-families (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- ACLU. 2018b. No, the Government Did Not Make the Deadline to Reunify Children with Their Parents. Available online: https://www.aclu.org/blog/immigrants-rights/immigrants-rights-and-detention/no-government-did-not-make-deadline-reunify (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- ACLU. 2018c. Fact-Checking Family Separation. Available online: https://www.aclu.org/blog/immigrants-rights/immigrants-rights-and-detention/fact-checking-family-separation (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- ACLU. 2018d. Family Separation by the Numbers. Available online: https://www.aclu.org/issues/immigrants-rights/immigrants-rights-and-detention/family-separation (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Ainsley, Julia, and Didi Martinez. 2019. What ICE did and did not do for kids left behind by Mississippi raids. NBC News. August 9. Available online: https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/immigration/what-ice-did-did-not-do-kids-left-behind-mississippi-n1040776?cid=emlnbn20190809 (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Alstein, Howard, and Rita J. Simon. 1991. Intercountry Adoption—A Multiple Perspective. New York: Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. 2013. Guidelines for psychological evaluations in child protection matters. American Psychological Association 68: 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Associated Press. 2018. Deported parents may lose kids to adoption, investigation finds. NBC News. October 9. Available online: https://www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/deported-parents-may-lose-kids-adoption-investigation-finds-n918261 (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Associated Press. 2019. Soap, sleep essential to migrant kids’ safety, according to panel of judges. Public Broadcasting Service. August 15. Available online: https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/soap-sleep-essential-to-migrant-kids-safety-according-to-panel-of-judges (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Ataiants, Janna, Chari Cohen, Amy Henderson Riley, Jamile Tellez Lieberman, Mary Clare Reidy, and Mariana Chilton. 2018. Unaccompanied children at the United States border, a human rights crisis that can be addressed with policy change. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 20: 1000–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BBC News. 2018. Honduras country profile. BBC News. May 16. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-18954311 (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- BBC News. 2019. Migrant children in the US: The bigger picture explained. BBC News. July 2. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-44532437 (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Bromfield, Nicole Footen, and Karen Smith Rotabi. 2012. Human trafficking and the Haitian child abduction attempt: Policy analysis and implications for social workers and NASW. Journal of Social Work Values and Ethics 9: 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bunkers, Kelley McCreery. 2010. Informal Family-Based Care Options: Protecting Children’s Rights? A Case Study of Gudifecha in Ethiopia. Master’s of Advanced Studies in Children’s Rights dissertation, Institut Universitaire Kurt Bosch and Université de Fribourg, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- Bunkers, Kelly McCreery, and Victor Groza. 2012. Intercountry adoption and child welfare in Guatemala: Lessons learned pre and post ratification of the 1993 Hague Convention on the Protection of Children and Cooperation in Respect of Intercountry Adoption. In Intercountry Adoption: Policies, Practices, and Outcomes. Edited by Judith L. Gibbons and Karen Smith Rotabi. Surrey: Ashgate Press, pp. 119–31. [Google Scholar]

- Bunkers, Karen McCreery, Victor Groza, and Daniel Lauer. 2009. International adoption and child protection in Guatemala: A case of the tail wagging the dog. International Social Work 52: 649–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnett, John, and Vanessa Romo. 2019. Guatemalan toddler apprehended at U.S. border dies after weeks in hospital. National Public Radio. May 16. Available online: https://www.npr.org/2019/05/16/ 723984077/guatemalan-toddler-apprehended-at-u-s-border-dies-after-weeks-in-hospital (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Castillo, Mariano. 2012. Undocumented immigrant mother loses adoption battle. CNN. July 18. Available online: https://www.cnn.com/2012/07/18/us/missouri-immigrant-child/index.html (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Catholic Legal Immigration Network, Public Counsel, Goodwin Procter LLP, and Kids in Need of Defense (KIND). 2019. Court Order Blocks New Asylum Policy Affecting Unaccompanied Immigrant Children. August 5. Available online: https://supportkind.org/media/court-order-blocks-new-asylum-policy-affecting-unaccompanied-immigrant-children/ (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Center for Gender and Refugee Studies of the University of California Hastings College and the Migration & Asylum Program Justice and Human Rights Center of the National University of Lanús. 2015. Childhood and Migration in Central and North America: Causes, Policies, Practices and Challenges. Available online: https://www.justice.gov/eoir/file/882926/download (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Chapin, Angelina. 2019. In their own words, migrant children describe horrific conditions at border patrol facilities. HuffPost. June 28. Available online: https://www.huffpost.com/entry/migrant-children-describe-detention_n_5d1646ffe4b03d61163af666 (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- CICIG. 2010. Report on Players Involved in the Illegal Adoption Process in Guatemala Since the Entry into Force of the Adoption Law (Decree 77-2007). Available online: http://cicig.org/uploads/documents/informes/INFOR-TEMA_DOC05_20101201_EN.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- DHS. 2018. ICE’s inspections and monitoring of detention facilities do not lead to sustained compliance or systemic improvements. Office of Inspector General. Available online: https://www.oig.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/assets/2018-06/OIG-18-67-Jun18.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Dickens, Jonathan. 2009. Social Policy Approaches to Intercountry Adoption. International Social Work 52: 595–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickerson, Caitlin. 2019. The youngest child separated from his family at the border was 4 months old. The New York Times. June 16. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/16/us/baby-constantine-romania-migrants.html?action=click&module=RelatedLinks&pgtype=Article (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Durkee, Ellen. 1982. Special problems of custody for unaccompanied refugee children in the United States. Michigan Journal of International Law 3: 197–225. [Google Scholar]

- Durran, Mary. 1993. New Internationalist. Stealing Children: Northern Couples Who “Legally” Adopt Children from Honduras May Never Imagine That the Children Have Been Stolen from Their Mothers. Available online: https://www.questia.com/read/1P3-450770921/stealing-children-northern-couples-who-legally (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Engel, Eliot L. 2019. Chairmen Engel, Nadler, and Thompson call on Trump to end Unlawful Safe Third Country Negotiations: State Department Human Rights Report Shows Guatemala and Mexico Agreements Would be Contrary to U.S. Law. June 27. Available online: https://engel.house.gov/latest-news/chairman-engel-nadler-and-thompson-call-on-trump-to-end-unlawful-safe-third-country-negotiations/ (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Estefan, Lianne Fuino, Katie A. Ports, and Tracy Hipp. 2017. Unaccompanied Children Migrating from Central America: Public Health Implications for Violence Prevention and Intervention; Betseda: National Center for Biotechnology Information. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5812021/ (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Filipovic, Jill. 2019. I can no longer continue to live here. Politico Magazine. Available online: https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2019/06/07/domestic-violence-immigration-asylum-caravan-honduras-central-america-227086 (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Fowler, Sarah. 2019. Where are my parents? School on standby to help children in aftermath of ICE raids. USA Today. Available online: https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2019/08/08/ice-raids-mississippi-undocumented-workers-arrested-kids-worry/1952572001/?fbclid=IwAR1ZdRhA4e0Evcknt%20Hhf5k2bX0hEVVXgv%20AD2IFIczD0pzgWI5QIhHEg_Irg (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Gallagher, Dianne. 2019. 680 undocumented workers arrested in record-setting immigration sweep on the first day of school. CNN. Available online: https://www.cnn.com/2019/08/08/us/mississippi-immigration-raids-children/index.html (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Gendle, Matthew H., and Carmen C. Monico. 2017. The balloon effect: The role of US drug policy in the displacement of unaccompanied minors from the Central American northern triangle. Journal of Trafficking, Organized Crime and Security 3: 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Goldschmidt, Ilse. 1986. National and intercountry adoptions in Latin America. International Social Work 29: 257–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, Richard. 2019. ACLU: Administration is still separating migrant families despite court order to Stop. National Public Radio. July 30. Available online: https://www.npr.org/2019/07/30/746746147/aclu-administration-is-still-separating-migrant-families-despite-court-order-to-?utm_campaign=storyshare (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Gzesh, Susan. 2019. “Safe Third Country” agreements with Mexico and Guatemala would be unlawful. Just Security. July 15. Available online: https://www.justsecurity.org/64918/safe-third-country-agreements-with-mexico-and-guatemala-would-be-unlawful/ (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Haag, Matthew. 2019. Thousands of immigrant children said they were sexually abused in U.S. detention centers, report says. The New York Times. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/27/us/immigrant-children-sexual-abuse.html (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- HCCH. 1993a. Convention of 29 May 1993 on Protection of Children and Co-Operation in Respect of Intercountry Adoption. Available online: https://www.hcch.net/en/instruments/conventions/full-text/?cid=69 (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- HCCH. 1993b. Explanatory Report on the 1993 Hague Intercountry Adoption Convention. Available online: https://www.hcch.net/en/publications-and-studies/details4/?pid=2279 (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- HCCH. 2008. Guatemala: Annual Adoption Statistics 1997–2005. Available online: http://hcch.e-vision.nl/upload/adostats_gu.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- HCCH. 2011. Status Table 33: Convention of 29 May 1993 on Protection of Children and Co-operation in Respect of Intercountry Adoption. Available online: https://www.hcch.net/en/instruments/conventions/status-table/?cid=69 (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Hennessy-Fiske, Molly. 2019. Guatemalan 16-year-old boy dies in U.S. custody after crossing the border. Los Angeles Times. Available online: https://www.latimes.com/nation/la-na-border-migrant-youth-death-20190501-story.html (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Herrmann, Kenneth, and Barbara Kasper. 1992. International adoption: The exploitation of women and children. Affilia 7: 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollingsworth, Lselie Doty. 2003. International adoption among families in the United States: Considerations of social justice. Social Work 48: 209–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Human Rights Watch. 2018. Honduras Events of 2018. Available online: https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2019/country-chapters/honduras (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Ingber, Sasha. 2019. Third child dies in U.S. government custody since December. National Public Radio. Available online: https://www.npr.org/2019/05/02/719409488/third-child-dies-in-u-s-government-custody-since-december (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Instituto Latinoamericano para la Educación y la Comunicación, ILPEC [Latin American Institute for Education and Communication]. 2000. Adopción y los derechos del niño en Guatemala [Adoption and the rights of the child in Guatemala]. Available online: https://www.brandeis.edu/investigate/adoption/docs/InformedeAdopcionesFundacionMyrnaMack.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Jawetz, Tom, and Scott Shuchart. 2019. Language access has life-or-death consequences for migrants. Center for American Progress. Available online: https://www.americanprogress.org/ issues/immigration/reports/2019/02/20/466144/language-access-life-death-consequences-migrants/ (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Jordan, Miriam. 2018. ‘It’s horrendous’: The heartache of a migrant boy taken from his father. The New York Times. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/07/us/children-immigration-borders-family-separation.html (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- King, Shaun. 2018. Encarnación Bail Romero’s story is a harrowing reminder of the stakes for separated migrant families. The Intercept. Available online: https://theintercept.com/2018/07/11/separated-children-encarnacion-bail-romero/ (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Rocio, Labrador, and Danielle Renwick. 2018. Central America’s violent northern triangle. Council on Foreign Relations. June 26. Available online: https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/central-americas-violent-northern-triangle (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- MacGill, Dan. 2018. Christian non-profit faces scrutiny over government foster care contract for separated children. Snopes News. June 26. Available online: https://www.snopes.com/news/2018/06/26/bethany-christian-services-family-separation-betsy-devos/ (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- MacLean, Sarah A., Priscilla O. Agyeman, Joshua Walther, Elizabeth K. Singer, Kim A. Baranowski, and Craig L. Katz. 2019. Mental health of children held at a United States immigration detention center. Social Science & Medicine 230: 303–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merchant, Nomaan. 2019. 4th migrant child dies in U.S. custody since December. Public Broadcasting Service. Available online: https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/4th-migrant-child-dies-in-u-s-custody-since-december (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Monico, Carmen. 2013. Implications of Child Abduction for Human Rights and Child Welfare Systems: A Constructivist Inquiry of the Lived Experience of Guatemalan Mothers Publically Reporting Child Abduction for Intercountry Adoption. Ph.D. dissertation, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, USA. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10156/4373 (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Monico, Carmen, and Karen Smith Rotabi. 2012. Truth, reconciliation and searching for the disappeared children of civil war: El Salvador’s search and reunion model defined. In Intercountry Adoption: Policies, Practices, and Outcomes. Edited by Judith L. Gibbons and Karen Smith Rotabi. Surrey: Ashgate, pp. 301–10. [Google Scholar]

- Monico, Carmen, Karen Smith Rotabi, and Justin Lee. 2019a. Forced child–family separations on the southwestern U.S. border under the “zero-tolerance” policy: Preventing human rights violations and child abduction into adoption (Part 1). Journal of Human Rights and Social Work 4: 164–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monico, Carmen, Karen Rotabi, Yvonne Vissing, and Justin Lee. 2019b. Forced child–family separations in the southwestern U.S. border under the “zero-tolerance” policy: The adverse impact on well-being of migrant children (Part 2). Journal of Human Rights and Social Work 4: 180–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, Amna, and Frazee Gretchen. 2019. ‘Why did you leave me?’ In new testimonies, migrants describe the ‘torment’ of child separation. PBS. Available online: https://www.pbs.org/newshour/ nation/why-did-you-leave-me-in-new-testimonies-migrants-describe-the-torment-of-child-separation (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- O’Halloran, Kerry, ed. 2006. Intercountry adoption. In The Politics of Adoption. Amsterdam: Springer, pp. 263–89. [Google Scholar]

- Polaris. n.d. Current Federal Laws. Available online: https://polarisproject.org/current-federal-laws (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Public Law 96-212. 1980 March 17. Available online: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-94/pdf/STATUTE-94-Pg102.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Rappleye, Hannah, and Lisa Riordan Seville. 2019. 24 immigrants have died in ICE custody during the Trump administration. NBC News. June 9. Available online: https://www.nbcnews.com/ politics/immigration/24-immigrants-have-died-ice-custody-during-trump-administration-n1015291 (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Redeen, Susan. 2014. U.S. Supreme Court declines to consider area adoption case. The Joplin Globe. Available online: https://www.joplinglobe.com/news/local_news/u-s-supreme-court-declines-to-consider-area-adoption-case/article_3479fa7a-11a9-5d87-a08b-613608d32e45.html (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Reichert, Elizabeth. 2003. Social Work and Human Rights: A Foundation for Policy and Practice. New York: Columbia University. [Google Scholar]

- REMHI [Recuperación de la Memoria Histórica or Recovery of the Historical Memory]. 1999. Guatemala Never again! Maryknoll: Orbis. [Google Scholar]

- Roby, Jini L. 2007. From rhetoric to best practice: Children’s rights in intercountry adoption. Children’s Legal Rights Journal 27: 48–71. [Google Scholar]

- Roby, Jini L., and Jim Ife. 2009. Human rights, politics and intercountry adoption: An examination of two sending countries. International Social Work 52: 661–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roby, Jini L., Karen Smith Rotabi, and Kelly McCreery Bunkers. 2013. Social justice and intercountry adoptions: The role of the U.S. social work community. Social Work 58: 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Root, Jay. 2019. How one migrant family got caught between smugglers, the cartel and Trump’s zero-tolerance policy. The Texas Tribune. Available online: https://www.texastribune.org/2019/03/07/migration-us-border-generating-billions-smugglers/ (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Ross, Brian, and Angela M. Hill. 2012. Tug-of-love: Immigrant mom loses effort to regain son given to US parents. In ABC News. Available online: https://abcnews.go.com/Blotter/immigrant-mom-loses-effort-regain-son-us-parents/story?id=16803067 (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Rotabi, Karen Smith. 2007. Ecological theory origin from natural to social science or vice versa? A brief conceptual history for social work. Advances in Social Work 8: 113–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotabi, Karen Smith. 2009. Guatemala City: Hunger protests amid allegations of child kidnapping and adoption fraud. Social Work and Society News Magazine. Available online: http://www.socmag.net/?p=540 (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Rotabi, Karen Smith, and Kelly McCreery Bunkers. 2008. Intercountry adoption reform based on the Hague Convention on Intercountry Adoption: An update on Guatemala in 2008. Social Work and Society News Magazine. Available online: http://www.socmag.net/?p=435 (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Rotabi, Karen Smith, Morris Alexandra W., and Weil Marie O. 2008. International child adoption in a post-conflict society: A multi-systemic assessment of Guatemala. Journal of Intergroup Relations 35: 9–41. [Google Scholar]

- Rotabi, Karen Smith, Carmen Monico, and Kelly Bunkers. 2015. At this critical juncture in the era of reform: Reviewing 35 years of social work literature on intercountry adoption. In The Intercountry Adoption Debate: Dialogues Across Disciplines. Edited by Robert L. Ballard, Naomi H. Goodno, Robert F. Cochran and Jay A. Milbrandt. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Sacchetti, Maria. 2019. ACLU: U.S. has taken nearly 1,000 child migrants from their parents since judge ordered stop to border separations. The Washington Post. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/immigration/aclu-us-has-taken-nearly-1000-child-migrants-from-their-parents-since-judge-ordered-stop-to-border-separations/2019/07/30/bde452d8-b2d5-11e9-8949-5f36ff92706e_story.html (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Sanford, Victoria. 2003. Buried Secrets: Truth and Human Rights in Guatemala. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Sanford, Victoria. 2008. From genocide to feminicide: Impunity and human rights in twenty-first century Guatemala. Journal of Human Rights 7: 104–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selman, Peter. 2002. Intercountry adoption in the new millennium: The ‘‘quiet migration’’ revisited. Population Research and Policy Review 21: 205–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selman, Peter. 2006. Trends in intercountry adoption: Analysis of data from 20 receiving countries, 1998–2004. Journal of Population Research 42: 183–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selman, Peter. 2009. The rise and fall of intercountry adoption in the 21st century. International Social Work 52: 575–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selman, Peter. 2012. The rise and fall of intercountry adoption in the 21st century: Global trends from 2001 to 2010. In Intercountry Adoption: Policies, Practices, and Outcomes. Edited by Justin Lee, Gibbons and Karen Smith Rotabi. London: Ashgate Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sherman, Christopher, Martha Mendoza, and Garance Burke. 2019. US held record number of migrant children in custody in 2019. Associated Press. November 12. Available online: https://apnews.com/015702afdb4d4fbf 85cf5070cd2c6824 (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Smolin, David Mark. 2005. Intercountry adoption as child trafficking. Valparaiso University Law Review 39: 281–325. [Google Scholar]

- Smolin, David Mark. 2006. Child laundering: How the intercountry adoption system legitimizes and incentivizes the practices of buying, trafficking, kidnapping, and stealing children. Wayne Law Review 52: 113–200. [Google Scholar]

- Smolin, David Mark. 2007. Intercountry adoption and poverty: A human rights analysis. Capital University Law Review 36: 413–53. [Google Scholar]

- Smolin, David Mark. 2010. Child laundering and the Hague Convention on Intercountry Adoption: The future and past of intercountry adoption. Louisville Law Review 48: 441–98. [Google Scholar]

- Soboroff, Jacob. 2019. Emails show Trump admin had ‘no way to link’ separated migrant children to parents. NBC News. Available online: https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/immigration/emails-show-trump-admin-had-no-way-link-separated-migrant-n1000746 (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Spencer, Hsu, and Thompson Steve. 2018. U.S. returns 7-year-old Guatemalan boy taken from his mother at border. The Washington Post. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/public-safety/us-says-it-will-return-7-year-old-taken-from-guatemalan-mother-at-border-as-her-federal-lawsuit-gets-hearing/2018/06/21/cd20ffbe-7571-11e8-9780-b1dd6a09b549_story.html?noredirect=on&utm _term=.21476fed38b7 (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- 8 U.S. Code §1158 Asylum. 2008. Cornell Law School Legal Information Institute. Available online: https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1158 (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2013, Fact Sheet—How the Child Welfare System Works. Available online: https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubPDFs/cpswork.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2019a. Child welfare goals, legislation, and monitoring. Available online: https://training.cfsrportal.acf.hhs.gov/book/export/html/2987 (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2019b. Separated children placed in Office of Refugee Resettlement Care. In Office of Inspector General. Available online: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-BL-18-00511.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- U.S. Department of State. 2018. Annual Report on Intercountry Adoption. Available online: https://travel.state.gov/content/dam/NEWadoptionassets/pdfs/Tab%201%20Annual%20Report%20on%20Intercountry%20Adoptions.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- U.S. Department of State. 2019. Adoptions Statistics. Available online: https://travel.state.gov/content/travel/en/Intercountry-Adoption/adopt_ref/adoption-statistics.html (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- U.S. Government Accounting Office. 2015. Central America: Information on migration of unaccompanied children from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. In GAO Highlights, GAO-15-362; Washington: Government Accounting Office. Available online: https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-15-362 (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- U.S. Office of the Federal Registrar. 2019. Apprehension, processing, care, and custody of alien minors and unaccompanied alien children. In Federal Register. Available online: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2019-08-23/pdf/2019-17927.pdf?fbclid=IwAR02E-mnrn6_FJGyQzg0YuIgASLS-vG09pp3B4eaLsUQpy3ZiyXkkpqRcZo (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- United Nations. 1948. Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Available online: http://www.un.org/en/documents/udhr/ (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- United Nations. 1989. Convention on the Rights of the Child. Available online: http://www2.ohchr.org/english/law/pdf/crc.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- United Nations. 2000. Convention against Transnational Organized Crime and the Protocols Thereto. Available online: https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/organized-crime/intro/UNTOC.html (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- United Nations. 2010. Guidelines for the Alternative Care of Children. Available online: http://www.crin.org/docs/Guidelines-English.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- United Nations. 2014. Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Sale of Children, Child Prostitution and Child Pornography on Her Follow-Up Visit to Honduras (21–25 April 2014). Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/Children/SR/A-HRC-28-56-Add1_ar.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). 2016. Broken Dreams: Central American Children’s Dangerous Journey to the United States. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/files/UNICEF_Child_Alert_Central_America_2016_report_final(1).pdf (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. 2010. Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/en-us/protection/basic/3b66c2aa10/convention-protocol-relating-status-refugees.html (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. 2014. Children on the Run. Available online: http://www.unhcrwashington.org/sites/default/files/1_UAC_ Children%20on%20the%20Run_Full%20Report.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner. 2018a. Committee on the Rights of the Child Examines Report of El Salvador. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=23594& LangID=E (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner. 2018b. Committee on the Rights of the Child Examines Report of Guatemala. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=22591& LangID=E (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- USCIS. 2019. Policy Manual, Chapter 11—Inadmissibility Determination. Available online: https://www.uscis.gov/policy-manual/volume-8-part-b-chapter-11 (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- USCIS. n.d. Inadmissibility and Waivers. Available online: https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/USCIS/About%20Us/Electronic%20Reading%20Room/Applicant%20Service%20Reference%20Guide/Inadmissibillity_and_Waivers.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Weil, Richard H. 1984. International adoptions: The quiet migration. International Migration Review 18: 276–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, Janet A., Andres G. Viana, Stephen A. Petrill, and Matthew D. Mathias. 2007. Interventions for internationally adopted children and families: A review of the literature. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal 24: 285–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. 2019. The World Bank in Honduras—Overview. Washington: World Bank. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/honduras/overview (accessed on 2 December 2019).

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Monico, C.; Mendez-Sandoval, J. Group and Child–Family Migration from Central America to the United States: Forced Child–Family Separation, Reunification, and Pseudo Adoption in the Era of Globalization. Genealogy 2019, 3, 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy3040068

Monico C, Mendez-Sandoval J. Group and Child–Family Migration from Central America to the United States: Forced Child–Family Separation, Reunification, and Pseudo Adoption in the Era of Globalization. Genealogy. 2019; 3(4):68. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy3040068

Chicago/Turabian StyleMonico, Carmen, and Jovani Mendez-Sandoval. 2019. "Group and Child–Family Migration from Central America to the United States: Forced Child–Family Separation, Reunification, and Pseudo Adoption in the Era of Globalization" Genealogy 3, no. 4: 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy3040068

APA StyleMonico, C., & Mendez-Sandoval, J. (2019). Group and Child–Family Migration from Central America to the United States: Forced Child–Family Separation, Reunification, and Pseudo Adoption in the Era of Globalization. Genealogy, 3(4), 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy3040068