Papering the Origins: Place-Making, Privacy, and Kinship in Spanish International Adoption

Abstract

1. Introduction

Kinship, Place, and Privacy on Paper

2. Ethnographic Setting and Methods

3. Discussion

3.1. Truth and Falsity

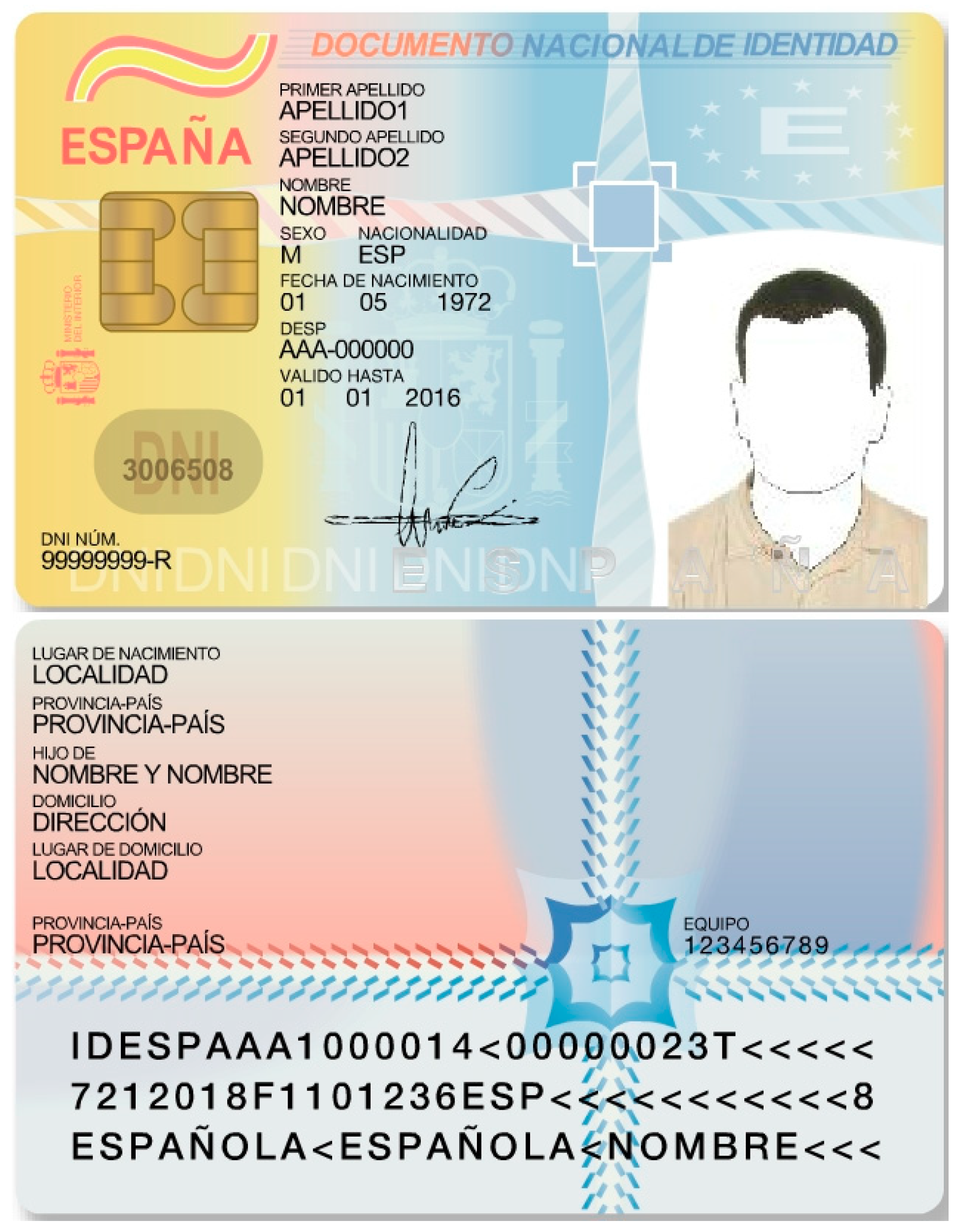

3.2. The Material Document

3.3. Secrecy and Kinship

4. Conclusions

“the traditional family ideal’s ideas about place, space, and territory suggest that families, racial groups, and nation-states require their own unique places or ‘homes’. Because ‘homes’ provide spaces of privacy and security for families, races, and nation-states, they serve as sanctuaries for group members”.

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Legal Materials Referenced in the Text (in Chronological Order)

References

- Bergmann, Sven. 2011. Fertility Tourism: Circumventive Routes That Enable Access to Reproductive Technologies and Substances. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 36: 280–89. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bok, Sissela. 1989. Secrets: On the Ethics and Concealment of Revelation. New York: Vintage Books. [Google Scholar]

- Boswell, John. 1988. The Kindness of Strangers: The Abandonment of Children in Western Europe from Late Antiquity to the Renaissance. New York: Pantheon Books. [Google Scholar]

- Carp, E. Wayne. 1998. Family Matters: Secrecy and Disclosure in the History of Adoption. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, E. Summerson. 2010. Scripting Addiction: The Politics of Therapeutic Talk and American Sobriety. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ceasar, Rachel Carmen. 2016. Kinship across Conflict: Family Blood, Political Bones, and Exhumation in Contemporary Spain. Social Dynamics 42: 352–69. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, Julie. 2009. Identification Papers and the Pursuit of Burial Rights in Fuzhou. In Between Life and Death: Governing Populations in an Era of Human Rights. Edited by Sabine Berking and Magdalena Zolkos. Frankfurt: Peter Lang, pp. 199–216. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, Patricia Hill. 1998. It’s All in the Family: Intersections of Gender, Race, and Nation. Hypatia 13: 62–82. [Google Scholar]

- De Graeve, Katrien. 2013. Festive Gatherings and Culture Work in Flemish-Ethiopian Adoptive Families. European Journal of Cultural Studies 16: 548–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Justicia (España). 2011. ¿Cómo se adquiere la nacionalidad española? Available online: https://www.mjusticia.gob.es/cs/Satellite/Portal/es/ciudadanos/nacionalidad/nacionalidad/como-adquiere-nacionalidad/espanoles-origen (accessed on 13 August 2019).

- Dorow, Sara K. 2006. Transnational Adoption: A Cultural Economy of Race, Gender, and Kinship, Nation of Newcomers. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison, Susan. 2018. Domesticating Democracy: The Politics of Conflict Resolution in Bolivia. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fassin, Didier. 2005. The Truth from the Body: Medical Certificates as Ultimate Evidence for Asylum Seekers. American Anthropologist 107: 597–608. [Google Scholar]

- Fessler, Ann. 2006. The Girls Who Went Away: The Hidden History of Women Who Surrendered Children for Adoption in the Decades before Roe V. Wade. New York: Penguin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, Michel. 2001. Governmentality. In Essential Works of Foucault, 1954–1984. Edited by James D. Faubion. London: Penguin, pp. 201–22. First published 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Frekko, Susan E., Jessaca B. Leinaweaver, and Diana Marre. 2015. How (not) to talk about adoption in Spain. American Ethnologist 42: 703–19. [Google Scholar]

- Garzón, Baltasar. 2008. Auto, Administración de Justicia, Juzgado Central de Instrucción No. 5. Madrid: Audiencia Nacional, vol. 53. [Google Scholar]

- Gay, Paloma, and Paloma Blasco. 2012. ‘A Wondrous Adventure’: Mutuality and Individuality in Internet Adoption Narratives. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 18: 330–48. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, Erving. 1963. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. New York: Touchstone. [Google Scholar]

- Goldfarb, Kathryn. 2018. Beyond Blood Ties: Intimate Kinships in Japanese Foster and Adoptive Care. In Intimate Japan: Ethnographies of Closeness and Conflict. Edited by Allison Alexy and Emma E. Cook. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, pp. 181–98. [Google Scholar]

- Gordillo, Gastón. 2006. The Crucible of Citizenship: ID-Paper Fetishism in the Argentinean Chaco. American Ethnologist 33: 162–76. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, Akhil, and James Ferguson. 1992. Beyond “Culture”: Space, Identity, and the Politics of Difference. Cultural Anthropology 7: 6–23. [Google Scholar]

- Herzfeld, Michael. 1997. Cultural Intimacy: Social Poetics in the Nation-State. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Howell, Signe. 2003. Kinning: The Creation of Life Trajectories in Transnational Adoptive Families. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 9: 465–84. [Google Scholar]

- Howell, Signe, and Diana Marre. 2006. To Kin a Transnationally Adopted Child in Norway and Spain: The Achievement of Resemblances and Belonging. Ethnos 71: 293–316. [Google Scholar]

- Hull, Mathew S. 2012. Documents and Bureaucracy. Annual Review of Anthropology 41: 251–67. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson, Heather. 2008. Culture Keeping: White Mothers, International Adoption, and the Negotiation of Family Difference. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Kay Ann. 2016. China’s Hidden Children: Abandonment, Adoption, and the Human Costs of the One-Child Policy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kertzer, David I., and Dominique Arel. 2002. Census and Identity: The Politics of Race, Ethnicity, and Language in National Census, New Perspectives on Anthropological and Social Demography. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Labov, William. 1966. The Social Stratification of English in New York City, Urban Language Series. Washington, DC: Center for Applied Linguistics. [Google Scholar]

- Lamphere, Louise. 2001. Whatever Happened to Kinship Studies? Reflections of a Feminist Anthropologist. In New Directions in Anthropological Kinship. Edited by Linda Stone. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, pp. 21–47. [Google Scholar]

- Leinaweaver, Jessaca B. 2011. Kinship Paths to and from the New Europe: A Unified Analysis of Peruvian Adoption and Migration. Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Anthropology 16: 380–400. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Leinaweaver, Jessaca B. 2013. Adoptive Migration: Raising Latinos in Spain. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leinaweaver, Jessaca B. 2014. The Quiet Migration Redux: International Adoption, Race, and Difference. Human Organization 73: 62–71. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Leinaweaver, Jessaca B. 2015a. How Internationally Adoptive Parents Become Transnational Parents: ‘Cultural’ Orientation as Transnational Care. In Anthropological Perspectives on Care: Work, Kinship, and the Life-Course. Edited by Erdmute Alber and Heike Drotbohm. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Leinaweaver, Jessaca B. 2015b. Transnational Fathers, Good Providers, and the Silences of Adoption. In Globalized Fatherhood. Edited by Marcia Inhorn, Wendy Chavkin and José-Alberto Navarro. New York: Berghahn Books, pp. 81–102. [Google Scholar]

- Leinaweaver, Jessaca, Diana Marre, and Susan Frekko. 2017. ‘Homework’ and Transnational Adoption Screening in Spain: The Co-Production of Home and Family. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 23: 562–79. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Leinaweaver, Jessaca, and Linda Seligmann. 2009. Introduction: Cultural and Political Economies of Transnational Adoption. Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Anthropology 14: 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Marín Corbera, Martí. 2010. la Gestación del Documento Nacional de Identidad: Un Proyecto de Control Totalitario para la España Franquista. In Novísima: Actas del Ii Congreso Internacional de Historia de Nuestro Tiempo. Edited by Carlos Navajas Zubeldía and Diego Iturriaga Barco. Logroño: Universidad de La Rioja, pp. 323–38. [Google Scholar]

- Marre, Diana. 2004. la Adopción Internacional y las Asociaciones de Familias Adoptantes: Un Ejemplo de Sociedad Civil Virtual Global. Scripta Nova 170: 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Marre, Diana. 2007. ‘I Want Her to Learn Her Language and Maintain Her Culture:’ ‘Transnational Adoptive Families’ Views of ‘Cultural Origins’. In Race, Ethnicity and Nation: Perspectives from Kinship and Genetics. Edited by Peter Wade. New York: Berghahn Books, pp. 73–95. [Google Scholar]

- Marre, Diana. 2011. Cambios en la Cultura de la AdopcióN y de la FiliacióN. In Familias: Historia de la Sociedad EspañOla (del Final de la Edad Media a Nuestros Días). Edited by Francisco Chacón and Joan Bestard. Madrid: Catedra, pp. 893–952. [Google Scholar]

- Mendo, Alberto. 2015. Los Padres de Niños Adoptados Denuncian la Discriminación de la FIFA Para Inscribir a sus Hijos. Antena 3 Noticias, October 20. Available online: https://www.antena3.com/noticias/sociedad/padres-ninos-adoptados-denuncian-discriminacion-fifa-inscribir-sus-hijos_20151020571e6a344beb287a291a569a.html (accessed on 17 September 2019).

- Modell, Judith S. 2002. A Sealed and Secret Kinship: The Culture of Policies and Practices in American Adoption. New York: Berghahn Books. [Google Scholar]

- Nash, Catherine. 2005. Geographies of Relatedness. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 30: 449–62. [Google Scholar]

- Navaro-Yashin, Yael. 2007. Make-Believe Papers, Legal Forms and the Counterfeit: Affective Interactions between Documents and People in Britain and Cyprus. Anthropological Theory 7: 79–98. [Google Scholar]

- OECD Spain. 2010. International Migration Outlook. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development, pp. 240–41. [Google Scholar]

- Paxson, Heather. 2010. Locating Value in Artisan Cheese: Reverse Engineering Terroir for New-World Landscapes. American Anthropologist 112: 444–57. [Google Scholar]

- Posocco, Silvia. 2011. Expedientes: Fissured Legality and Affective States in the Transnational Adoption Archives in Guatemala. Law, Culture and the Humanities 7: 434–56. [Google Scholar]

- Real Academia Española. 2018. Diccionario de la Lengua Española. Madrid: Real Academia Española. [Google Scholar]

- Reeves, Madeline. 2013. Clean Fake: Authenticating Documents and Persons in Migrant Moscow. American Ethnologist 40: 508–24. [Google Scholar]

- Riles, Annelise. 2006. Introduction: In Response. In Documents: Artifacts of Modern Knowledge. Edited by Annelise Riles. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Samuels, Elizabeth J. 2013. Surrender and Subordination: Birth Mothers and Adoption Law Reform. Michigan Journal of Gender and Law 20: 33–81. [Google Scholar]

- Seligmann, Linda. 2009. The Cultural and Political Economies of Adoption in Andean Peru and the United States. Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Anthropology 14: 115–39. [Google Scholar]

- Seligmann, Linda J. 2013. Broken Links, Enduring Ties: American Adoption across Race, Class, and Nation. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Selman, Peter. 2009. The Rise and Fall of Intercountry Adoption in the 21st Century. International Social Work 52: 575–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmel, Georg. 1906. The Sociology of Secrecy and of Secret Societies. American Journal of Sociology 11: 441–98. [Google Scholar]

- Skrabut, Kristin. 2014. Extreme Lives: The Unruly Domestication of Peruvian Poverty. Ph.D. Thesis, Brown University, Providence, RI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Sturm, Circe. 2002. Blood Politics: Race, Culture, and Identity in the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sturm, Circe. 2011. Becoming Indian: The Struggle over Cherokee Identity in the Twenty-First Century, 1st ed. School for Advanced Research Resident Scholar Series; Santa Fe: School for Advanced Research Press. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Children’s Fund. 2013. Every Child’s Birth Right: Inequities and Trends in Birth Registration. New York: UNICEF. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations General Assembly. 1989. Convention on the Rights of the Child, 20 November 1989. Treaty Series; San Francisco: United Nations. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/crc.aspx (accessed on 17 September 2019).

- Yngvesson, Barbara, and Susan Bibler Coutin. 2006. Backed by Papers: Undoing Persons, Histories, and Return. American Ethnologist 33: 177–90. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leinaweaver, J. Papering the Origins: Place-Making, Privacy, and Kinship in Spanish International Adoption. Genealogy 2019, 3, 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy3040050

Leinaweaver J. Papering the Origins: Place-Making, Privacy, and Kinship in Spanish International Adoption. Genealogy. 2019; 3(4):50. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy3040050

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeinaweaver, Jessaca. 2019. "Papering the Origins: Place-Making, Privacy, and Kinship in Spanish International Adoption" Genealogy 3, no. 4: 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy3040050

APA StyleLeinaweaver, J. (2019). Papering the Origins: Place-Making, Privacy, and Kinship in Spanish International Adoption. Genealogy, 3(4), 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy3040050