He Tātai Whenua: Environmental Genealogies

Abstract

:1. Explanatory Tools for Understanding the World

In te ao Māori, all of the myriad elements of creation—the living and the dead, the animate and inanimate—are seen as alive and inter-related. All are infused with mauri (that is, a living essence or spirit) and all are related through whakapapa... The people of a place are related to its mountains, rivers and species of plant and animal, and regard them in personal terms. Every species, every place, every type of rock and stone, every person (living or dead), every god, and every other element of creation is united through this web of common descent…

This system of thought provides intricate descriptions of the many parts of the environment and how they relate to each other. It asserts hierarchies of right and obligation among them... These rights and obligations are encompassed in another core value—kaitiakitanga. Kaitiakitanga is the obligation, arising from the kin relationship, to nurture or care for a person or thing. It has a spiritual aspect, encompassing not only an obligation to care for and nurture not only physical well-being but also mauri [life force]…

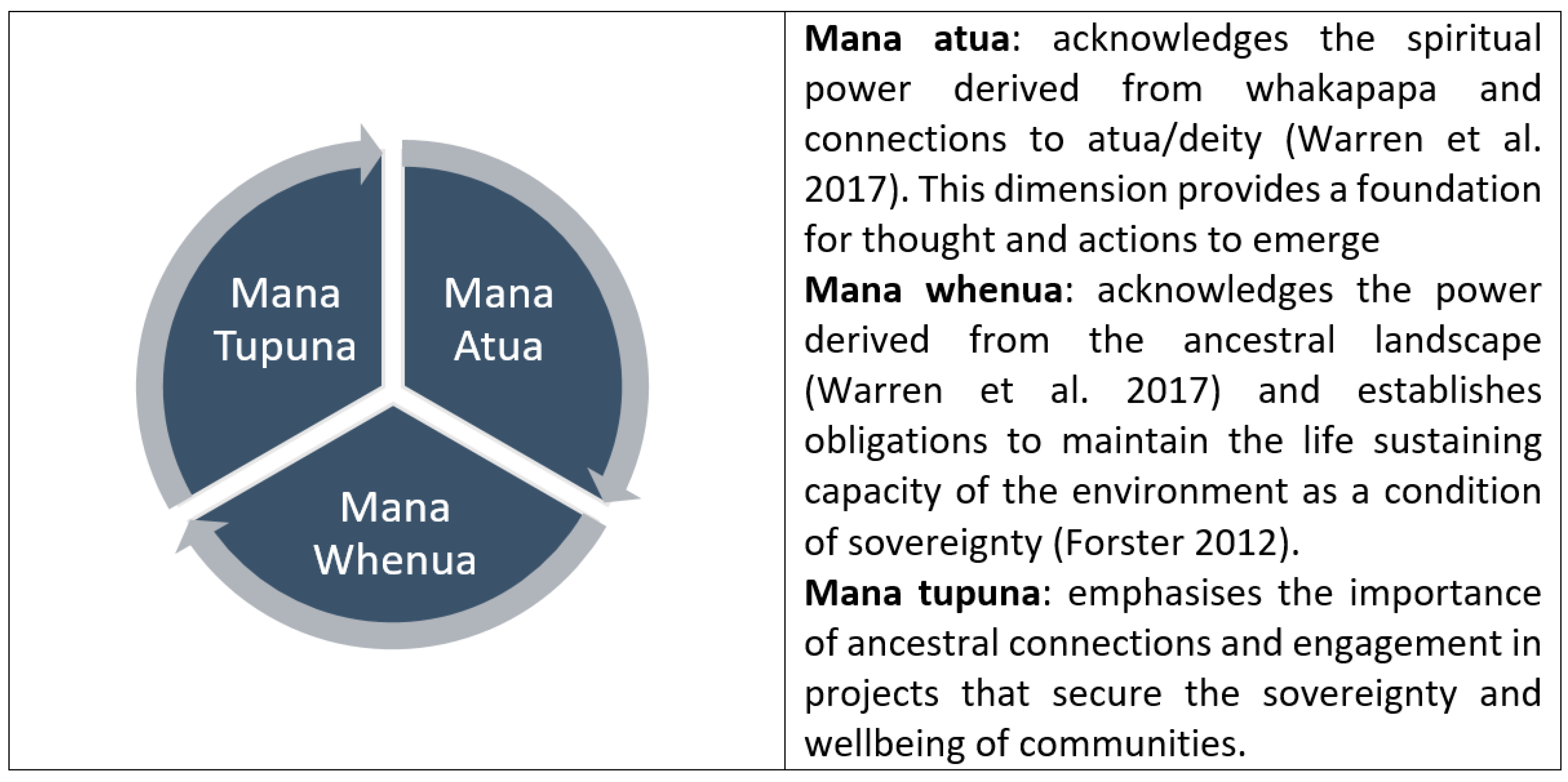

Enacting whakapapa or performing kinship obligations and responsibilities is intricately linked to tribal sovereignty. Conversely, when whakapapa is absent within day-to-day activities then connections to ancestors and the environment weaken. When this notion is applied to understanding social phenomena whakapapa can be used to trace and critique origin, complex connections and interactions—although is much more than just a chronological history of events. It can make explicit dominant imperatives whilst also making visible those imperatives that have failed to gain traction at specific junctures of time thereby inviting consideration of whether we can think or act differently.In the human realm, those who have mana [authority]… must exercise it in accordance with the values of kaitiakitanga—to act unselfishly, with right mind and heart, and with proper procedure. Mana and kaitiakitanga go together as right and responsibility, and that kaitiakitanga responsibility can be understood not only as a cultural principle but as a system of law.

2. Environmental Histories of Aotearoa New Zealand

2.1. Te Ao Māori/the Māori World

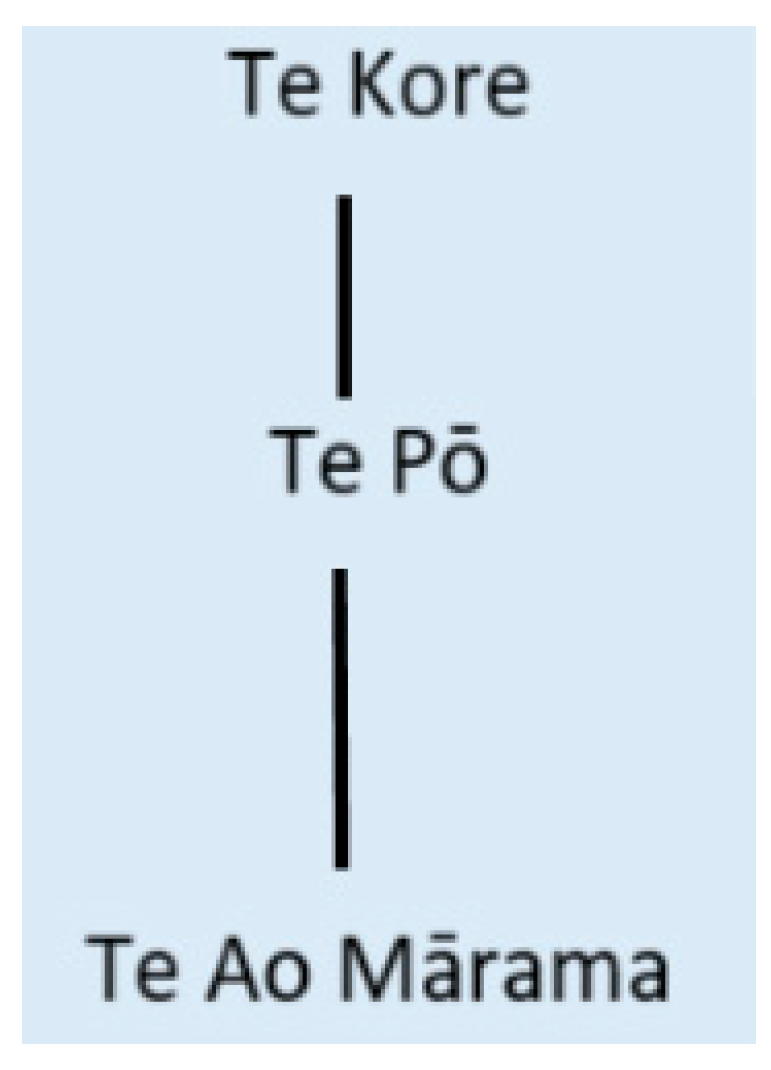

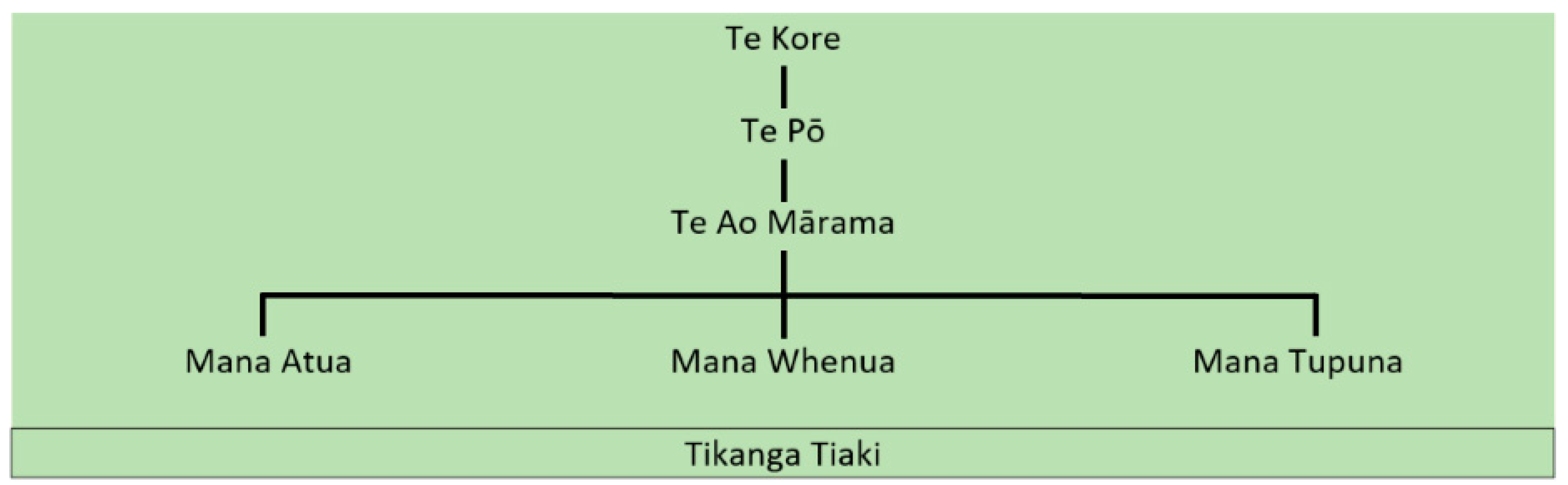

Every culture has its traditions about how the world was created. Māori have many of them, but the most important stories are those that tell how darkness became light, nothing became something, earth and sky were separated, and nature evolved.

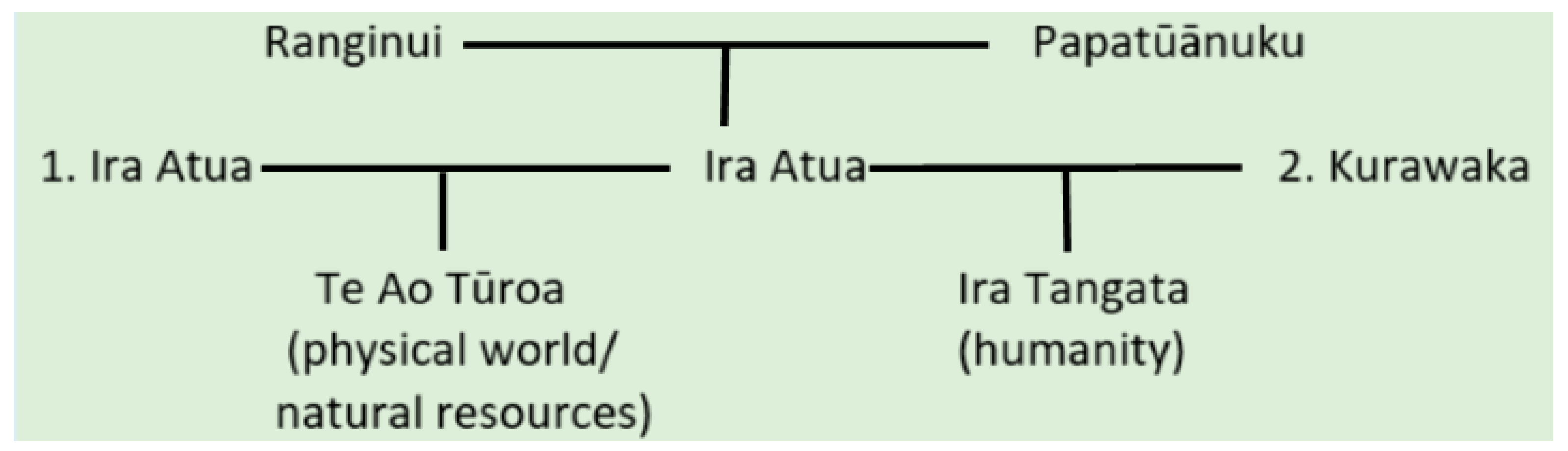

The children of Ranginui and Papatūānuku were born into Te Pō, the dark world of potential and when they thrust apart their parents Te Ao Mārama the world of light was created. It is in the world of light that natural resources and humanity emerged. Figure 3 is a whakapapa sequence depicting the origin of natural resources and humanity.In the Māori story of creation, the earth and sky came together and gave birth to some 70 children, who eventually thrust apart their parents and populated the world. Each of the children became the god of a particular domain of the natural world. Their children and grandchildren then became ancestors in that domain. For example, Tangaroa, god of the sea, had a son called Punga. Punga then had two children: Ikatere, who became the ancestor of the fish of the sea, and Tūtewehiwehi, who became the ancestor of the fish and amphibious lizards of inland waterways.

Hineahuone is the mother of humanity. She was formed from the Earth and imbued with the essence of the ira atua (Mikaere 2003). This is the origin of one of the names of the Māori people—tangata whenua meaning people of or from the Earth. Hineahuone gave birth to the first human form—Hinetītama (Mikaere 2003) creating a kinship relationship with the spiritual world as represented by Ranginui, Papatūānuku and their children and natural resources (Roberts et al. 1995; Royal 2003).The children of Ranginui and Papatūānuku had only talked of life… They had not experienced it for themselves, not in the physical forms that tormented their imaginations... [but] it was the human form that eluded… Papatūānuku waited until she knew the time was right, then led Tāne to her sacred place, to Kurawaka. This was where he fashioned me [Hineahuone] from the red clay he found there. I was the first. The first to breathe, to touch, to feel, to hold, to know, to experience everything of the newly created world.(Excerpts from the poem Hineahuone by Wiremu (Grace n.d.))

2.2. Te Ao Hurihuri/the Changing World

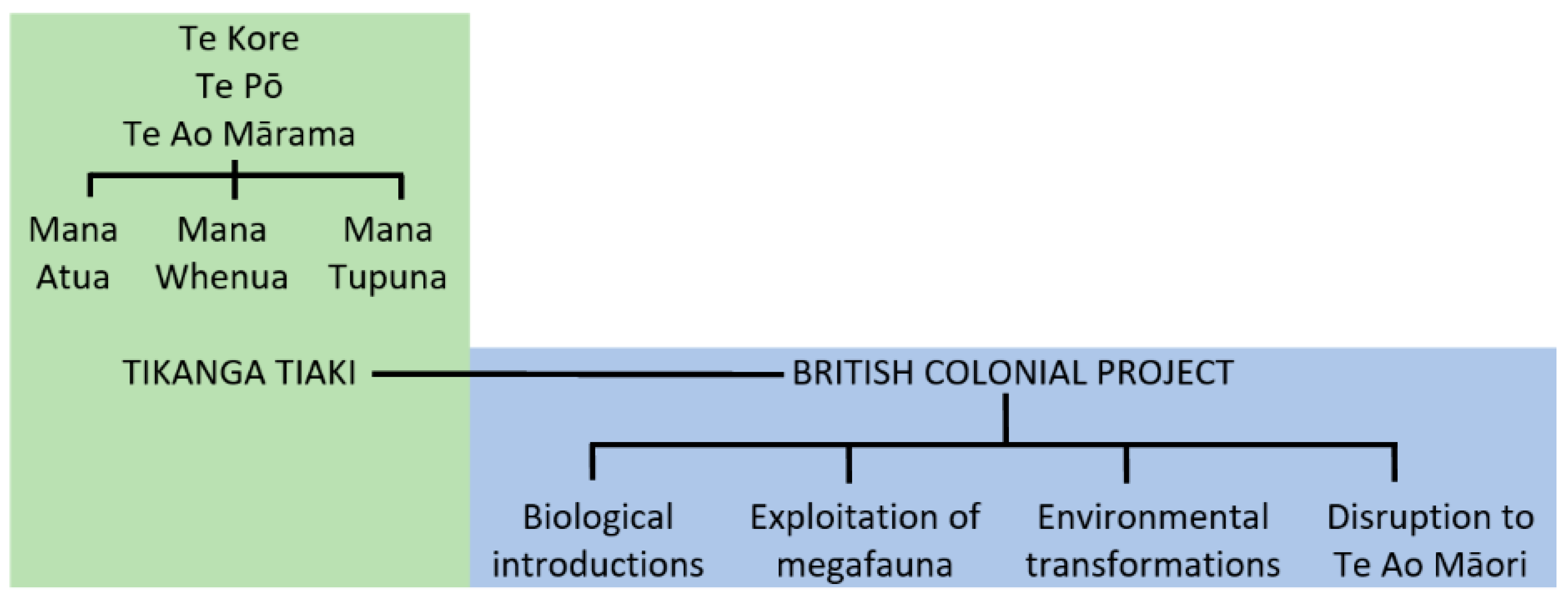

The British colonial project introduced new ideas, technologies and peoples to the Aotearoa New Zealand landscape. An abrupt change to authority over the environment emerged and Māori communities experienced widespread disruption to Te Ao Māori (Forster 2013a; Walker 1990). Figure 6 is a whakapapa sequence that demonstrates the interaction between the two dominant and contested environmental traditions—one derived from Te Ao Māori (a repeat of Figure 5), the other introduced by the British colonial project.An overriding feature of New Zealand’s environmental histories has been the use of land and water for successive waves of resource exploitation, for which reason this remains a country heavily dependent on a narrow range of primary exports. In the nineteenth century, wool, wheat and timber booms followed sealing and goldmining; in the twentieth century, the preoccupation was with the extraction of maximum value from grass-based commodities. Such resource ‘quarrying’, of living ‘off’ rather than ‘with’ the land, has been framed through systems of law, surveying, cartography and metrology... reveal[ing] how fragile and unstable are the land and waters so measured and appropriated... acquisition of intimate environmental knowledges through the senses of Māori has not always been replicated among Pākehā. The assumption of the colonial project of improvement has been that of an essentially benign, if not fixed or knowable, environmental stage, which is why the project has in its turn been portrayed as ‘fraught and vulnerable’.

However, Māori and supporters of a conservation agenda have continuously contested the emphasis on exploitative economies (Forster 2014, 2016; Young 2004). By the 1950s, a global movement for sustainability (McClean and Smith 2001) was also beginning to influence the direction of Aotearoa New Zealand’s environmental policy (Memon 1995); change was imminent.The effects of Māori hunting, fire and horticulture were extensive. But they were less dramatic than 200 years of Pākehā transformations, initiated as part of the European imperial drive to incorporate new territories into the capitalist world economy... There have been contests for land between Māori and Pākehā, vigorous throughout the nineteenth century and not forgotten by Māori since, and environmental interventions resulting in resource destruction, soil erosion and the spread of unwanted, and costly, pests and weeds.

2.3. Te Ao Tautohe/the Contested World

2.4. A Wetland Story

In the days of our forefathers and to the present day, the great lake has been a major source of food... The tangata whenua [local indigenous people] of Whakakī [derived] a total way of life from this lagoon and its tributaries. Their ancestors are buried... around the perimeters of the lagoons. The spiritual connections are strongly bonded between the land, lagoons and people. The heritage bonds give the tangata whenua their pride, their mana [power and prestige] and their spiritual culture.

This has now changed drastically due to the ecosystem being muddled with by engineers... The food source which the people of Whakakī relied on... has now almost disappeared... The river... has now silted up.

The letter points out that Whakakī Lake and wetland system in the Hawke’s Bay region of the North Island, New Zealand is a significant resource in the tribal territory of my ancestors. Survival as a people was dependent on this resource and the lake and associated natural resources are intricately linked to our mana and tribal identity. This letter provides examples of mana atua/spiritual power, mana whenua/power derived from ancestral landscape and mana tupuna/ancestral connections. For example, mana atua connections are referenced by the phrase “heritage bonds” and mana whenua is expressed through the desire to influence contemporary resource management decision-making. The intent was to ensure that mana tupuna responsibilities are maintained, particularly nurturing the wellbeing of natural resources and ensuring the survival of “heritage” for future generations of our people.In these changing times where a natural order of nature is fast disappearing we as kai tiaki (Trustees) of the environment should endeavour to maintain all natural resources. This is to ensure that future generations can grow up with a heritage that is a vital part of being Māori.(Letter written 25 May 1992 from Huki Solomon to the Parliamentary Commission for the Environment, Helen Hughes)

3. Discussion and Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Glossary

| Aotearoa | Māori name for New Zealand |

| hapū | Subtribe |

| Ira atua | Ancestral life principle |

| Ira tangata | Humanity |

| Kaitiakitanga | Māori environmental ethos and practices |

| Kaupapa Māori research | Approach to research based on Māori worldview and political agenda |

| Kōrero tuku iho | Genealogical narrative; narratives derived from whakapapa |

| Mahi mara | Gardening |

| Mahinga kai | Collection of wild foods |

| mana | Authority |

| Māori | Indigenous people of Aotearoa |

| Mauri | Life force |

| Mātauranga Māori/mātauranga | Māori knowledge |

| Pūrākau | Narratives |

| Te Tiriti o Waitangi | Treaty of Waitangi |

| Te whare tapa whā | Māori framework for conceptualising health based on the four-sided whare |

| Te wheke | Māori framework for conceptualising health based on the octopus |

| Tikanga | Actions |

| Rāhui | Restrictions to protect natural resources |

| Waiata | Songs |

| Whakapapa | genealogy |

| Whakataukī | Sayings |

| Wharenui | Tribal meeting house |

Names in Whakapapa Sequences (In Order of Appearance)

| Te Ao Māori | The Māori world |

| Te Ao Hurihuri | The changing world |

| Te Ao Tautohe | The contested world |

| Te Kore | World of darkness |

| Te Pō | World of potential |

| Te Ao Mārama | World of light |

| Ranginui | Sky father |

| Papatūānuku | Earth Mother |

| Tangaroa | God of sea |

| Punga | Son of Tangaroa |

| Ikatere | Offspring of Punga; ancestor of the fish of the sea |

| Tūtewehiwehi | Offspring of Punga; ancestor of the fish and lizards of inland waterways |

| Tāne | God of the forest |

| Te Ao Tūroa | The natural world |

| Kurawaka | Sacred place that held life principle of humanity |

| Mana atua | Power derived from whakapapa |

| Mana whenua | Power derived from ancestral landscapes |

| Mana tangata | Power linked to upholding the dignity and wellbeing of people |

| Tikanga tiaki | Guardianship customs |

References

- Awatere, Shaun, and Garth Harmsworth. 2014. Ngā Aroturukitanga Tika mō ngā Kaitiaki: Summary Review of Mātauranga Māori Frameworks, Approaches, and Culturally Appropriate Monitoring Tools for Management of Mahinga Kai. Hamilton: Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research. [Google Scholar]

- Belgrave, Michael, Merata Kawharu, and David Williams. 2004. Waitangi Revisited: Perspectives on the Treaty of Waitangi. Auckland: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Best, Elsdon. 1976. Māori Agriculture. Wellington: Shearer, Government Printer. [Google Scholar]

- Best, Elsdon. 1977a. Fishing Methods and Devices of the Māori. Wellington: Keating. [Google Scholar]

- Best, Elsdon. 1977b. Forest Lore of the Māori. Wellington: Keating. [Google Scholar]

- Bevir, Mark. 2010. Rethinking governmentality: Towards genealogies of governance. European Journal of Social Theory 13: 423–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boast, Richard. 1999. Māori Land Law. Wellington: Butterworths. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, Lyn. 2019. Aotearoa/New Zealand adaptation strategies and practices. In Indigenous Pacific Approaches to Climate Change. Palgrave Studies in Disaster Anthropology. Cham: Palgrave Pivot, pp. 71–84. [Google Scholar]

- Coombes, Brad, and Stephanie Hill. 2005. Fishing for the Land under Water—Catchment Management, Wetland Conservation and the Wairoa Coastal Lagoons. A Report Prepared for the Crown Forestry Rental Trust. Auckland: School of Geography and Environmental Science, University of Auckland. [Google Scholar]

- Durie, Mason. 1994. Whaiora: Māori Health Development. Auckland: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Durie, Mason. 1998. Te Mana te Kāwanatanga: The Politics of Māori Self-Determination. Auckland: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Forster, Margaret. 2012. Hei Whenua Papatipu: Kaitiakitanga and the Politics of Enhancing the Mauri of Wetlands. Ph.D. thesis, Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand. [Google Scholar]

- Forster, Margaret. 2013a. Imagining new futures: Kaitiakitanga and Agri-Foods. New Zealand Sociology 28: 9–32. [Google Scholar]

- Forster, Margaret. 2013b. Kaitiakitanga as Environmental Leadership. In Ara Mai He Tetekura—Visioning Our Futures. New and Emerging Pathways of Maori Academic Leadership. Edited by Paul Whitinui, Marewa Glover and Daniel Hikuroa. Dunedin: Otago University Press, pp. 112–20. [Google Scholar]

- Forster, Margaret. 2014. Indigeneity and trends in recognizing Māori environmental interests in Aotearoa New Zealand. Nationalism and Ethnic Politics 20: 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, Margaret. 2016. Indigenous environmental autonomy in Aotearoa New Zealand. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Scholarship 12: 316–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, Wiremu. n.d. A Trilogy of Wahine Toa. Available online: http://eng.mataurangamaori.tki.org.nz/Rauemitautoko/Te-Reo-Maori/Nga-Pakiwaitara-Maori-me-nga-Purakau-Onaianei/He-raupapa-toru-o-ngawahine-toa (accessed on 15 January 2019).

- Graham, James. 2009a. Nā Rangi tāua, nā Tūānuku e takato nei: Research methodology framed by whakapapa. MAI Review 1: 3. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, James. 2009b. Whakatangata Kia Kaha: Toitū te Whakapapa, Toitū te Tuakiri, Toitū te Mana. An Examination of the Contribution of Te Aute College to Māori Advancement. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand. Available online: https://mro.massey.ac.nz/handle/10179/1254 (accessed on 19 March 2019).

- Haami, Brad, and Mere Roberts. 2002. Genealogy as taxonomy. International Social Science Journal 54: 403–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, Aroha. 2004. Hikoi: Forty Years of Māori Protest. Wellington: Huia Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Hayward, Janine. 2003. Local Government and the Treaty of Waitangi. Victoria: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hayward, Janine, and Nicola Wheen. 2004. The Waitangi Tribunal. Te Roopu Whakamana i te Tiriti o Waitangi. Wellington: Bridget Williams Books. [Google Scholar]

- Kawharu, Merata. 2000. Kaitiakitanga: A Māori anthropological perspective of the Māori socio-environmental ethic of resource management. Journal of the Polynesian Society 109: 349–70. [Google Scholar]

- King, Darren, Wendy Shaw, Peter Meihana, and James Goff. 2018. Māori oral histories and the impact of tsunamis in Aotearoa New Zealand. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 18: 907–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClean, Robert, and Trecia Smith. 2001. The Crown and Flora and Fauna: Legislation, Policies, and Practices, 1983–98. Wellington: Waitangi Tribunal. [Google Scholar]

- Mead, Hirini Moko. 2003. Tikanga Māori: Living by Māori Values. Wellington: Huia Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Memon, Pyarali Ali. 1995. Keeping New Zealand Green. Recent Environmental Reforms; Wellington: Government Press.

- Mikaere, Ani. 2003. The Balance Destroyed: Consequences for Māori Women of the Colonisation of Tikanga Māori. Auckland: The International Research Institute for Māori and Indigenous Education. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, Te Kipa Keepa. 2004. A Tangata Whenua Perspective on Sustainability Using the Mauri Model: Towards Decision-Making Balance with Regard to Our Social, Economic, Environmental and Cultural Well-Being. Paper presented at the International Conference on sustainability Engineering and Science, Auckland, New Zealand, July 6–9. [Google Scholar]

- Pawson, Eric, and Tom Brooking. 2011. Seeds of Empire: The Environmental Transformation of New Zealand. London: I.B. Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Pawson, Eric, and Tom Brooking. 2013. Making a New Land: Environmental Histories of New Zealand. Dunedin: Otago University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pere, Rangimārie Rose. 1991. Te Wheke: A Celebration of Infinite Wisdom. Gisborne: Ao Ako Global Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Petrie, Hazel. 2006. Chiefs of Industry: Māori Tribal Enterprise in Early Colonial New Zealand. Auckland: Auckland University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, Mere, Waerete Norman, Nganeko Minhinnick, Dell Wihongi, and Carmen Kirkwood. 1995. Kaitiakitanga: Māori perspectives on conservation. Pacific Conservation Biology 2: 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochford, Tim. 2004. Whare tapa wha: A Māori model of a unified theory of health. The Journal of Primary Prevention 25: 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, Nikalos, Pat O’Malley, and Mariana Valverde. 2006. Governmentality. Annual Review of Law Society 2: 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royal, Te Ahukaramū Charles. 1998. Te Ao Mārama: A research paradigm. He Pukenga Kōrero 4: 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Royal, Te Ahukaramū Charles. 2003. The Woven Universe: Selected Writings of the Rev. Māori Marsden. Ōtaki: Estate of Rev. Māori Marsden. [Google Scholar]

- Royal, Te Ahukaramū Charles. 2005. Māori Creation Traditions. Te Ara—The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Available online: http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/maori-creation-traditions (accessed on 2 April 2019).

- Royal, Te Ahukaramū Charles. 2007. Te Ao Mārama—The Natural World—An Interconnected World. Te Ara—The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Available online: http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/te-ao-marama-the-natural-world/page-2 (accessed on 11 January 2019).

- Sadler, Hone. 2007. Mātauranga Māori (Māori Epistemology). International Journal of the Humanities 4: 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Linda Tuhiwai. 1999. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. London: Zed Books, Dunedin: University of Otago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Taonui, Rawiri. 2012. Māori urban protest movements. In Huia Histories of Māori: Ngā Tāhuhu Korero. Edited by Danny Keenan. Wellington: Huia Publishers, pp. 230–59. [Google Scholar]

- Tawhai, Veronica, and Katarina Gray-Sharp. 2011. ‘Always Speaking’: The Treaty of Waitangi and Public Policy. Wellington: Huia Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Rowan. 1997. The State of New Zealand’s Environment. Wellington: Ministry for the Environment, Manatū mō te Taiao, Wellington: GP Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Te Rito, Joe. 2007. Te Tīhoka me te Karo: Struggles and Transformation of Ngāti Hinemanu of Ōmahu. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand. [Google Scholar]

- Tipa, Gail, and Laurel D. Teirney. 2003. A Cultural Health Index for Streams and Waterways: Indicators for Recognising and Expressing Māori Values; Wellington: Ministry for the Environment.

- Waitangi Tribunal. 2011. Ko Aotearoa Tēnei. A Report into Claims Concerning New Zealand Law and Policy Affecting Māori Culture and Identity. Wellington: Legislation Direct. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, Ranginui. 1984. The genesis of Māori activism. Journal of the Polynesian Society 93: 267–82. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, Ranginui. 1990. Ka Whawhai Tonu Matou: Struggle without End. Auckland: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, Te Rina, Margaret Forster, and Veronica Tawhai. 2017. Tangata whenua: Māori identity and belonging. In Tūrangawaewae: Identity and Belonging in Aotearoa New Zealand. Edited by Trudie Cain, Ella Kahu and Richard Shaw. Auckland: Massey University Press, pp. 53–69. [Google Scholar]

- Young, David. 2004. Our Islands, Our Selves. Dunedin: University of Otago Press. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | For those readers unfamilar with this model te whare tapa wha is a tool for conceptualising wellbeing from a Māori perspective (Durie 1994; Rochford 2004) based on the metaphor of a four sided house. It emphasises that wellbeing is dependent on four interconnected cultural concepts or dimensions—taha wairua/the spiritual, taha hinengaro/the mental, taha whānau/the family and, taha tinana/the phyiscal. This model was developed to contest the dominant medical model of health that tends to focus on illness and physical dimensions. |

| 2 | Te wheke (Pere 1991) is another Māori health model with an emphasis on whānau/family. This model is depicted by te wheke/the octopus. The head represents the family and each of the tentacles a distinct cultural health concept. |

| 3 | Treaty of Waitangi; A treaty negotiating Māori and British sovereignty in Aotearoa New Zealand. |

| 4 | The genealogical narratives provided here are based on the author’s own tribal traditions—those of the Ngāti Kahungunu people. It is important to note that other tribes have their own traditions that can differ from the one described here. |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Forster, M. He Tātai Whenua: Environmental Genealogies. Genealogy 2019, 3, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy3030042

Forster M. He Tātai Whenua: Environmental Genealogies. Genealogy. 2019; 3(3):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy3030042

Chicago/Turabian StyleForster, Margaret. 2019. "He Tātai Whenua: Environmental Genealogies" Genealogy 3, no. 3: 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy3030042

APA StyleForster, M. (2019). He Tātai Whenua: Environmental Genealogies. Genealogy, 3(3), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy3030042