1. Introduction

In the summer of 2015, I was invited by Sámien giessieváhkkuo (a Sami community in the southern part of Swedish Sápmi, the traditional Sami area) to hold a seminar on reindeer husbandry. After the seminar a heated discussion arose, which centered on land title and indigenous rights. An older member of the community stood up and, in a broken voice, stated that he still had papers in his possession giving him land title over his ancestors’ traditional land. He was not a reindeer herder and, as the conversation progressed, it became clear that he wanted to use the land for hunting and fishing for his own subsistence. However, it was also an issue of belonging, as he sought acknowledgement of his Sami identity within the Sami community and outside, as well as recognition as a rightful inheritor of the land.

Being a historian in Sápmi, a Sami descendant, and with no relatives that are involved in reindeer husbandry, I can recall many similar discussions over the years, in which questions of genealogy, kinship, and place intersected with questions of identity and land rights. This is not surprising. On a global level, indigenous people’s identity processes, rights, and connections to place are often intertwined and complex. Aspects of colonialism, decolonization, acculturation, segregation, and enforced assimilation have influenced how indigenous identity is understood and practiced, and what rights accompany indigenous ‘status’ (

Åhrén 2008, p. 81;

Anaya 2004;

Hilder 2014, pp. 109–48;

Loomba 2007;

Minde 2008;

Moreton-Robinson 2003;

Snyder et al. 2003;

UN General Assembly 2007).

In Sweden, as well as in Norway, Finland, and Russia, Sami identity and culture, recognition, and rights are all constructed differently. However, in all contexts, Sami identity (which I will get back to later) is not necessarily expressed through, nor assessed, in relation to Sami status (electoral enrollment to Saemiedigkie). Sami Parliaments are acknowledged by and within the tree Nordic states, as political bodies representing the Sami people. People have to be included in the electoral register in order to elect representatives to the parliaments, and criteria for inclusion differ between the countries. Enrollment in all countries demand self-ascribing as Sami and is also evaluated in relation to language skills (

Gaski 2008). Although electoral enrollment is not automatically followed by (or follow with), Sami identity or -land rights (if any), to some inclusion in the political Sami community is important and ‘has both practical and symbolic significance due to power-related factors and collective recognition from the rest of the Sami community’ (

Sarivaara 2016, p. 196).

Sweden is somewhat unusual in a global context, in that Indigenous land rights are tied to the practice of a specific industry or livelihood—reindeer husbandry. Even though Sami in Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia practice reindeer husbandry, the regulations, practices, and legal framework surrounding reindeer husbandry differs greatly. In Sweden, the law and regulations on reindeer husbandry originates from the late 19th century, and it was connected to the Swedish government’s notion of Sami as primarily active in (and best suited for) reindeer husbandry. I argue that the notion, the legal framework building upon it, and how the two have been reproduced over time (within and outside the Sami community) have influenced Sami identity processes up until today.

In my writing I understand Sami identity as ‘a matter of “becoming” as well as of “being” (

Hall 1994, p. 394). Thus, it is fluent, borderless, and constantly negotiated and changed. I also see identity as a dialectal process between the self and social group(s). (

Pietikäinen and Dufva 2006). Today, Sami identity is continuously assessed both within and outside the Sami community (

Hirvonen and Anttonen 2008, pp. 111–8). It is unsurprising that connection to reindeer husbandry is a key factor influencing whether or not someone is recognized as Sami due to the current legislative landscape in Swedish Sápmi and its history (

Åhrén 2008). Inga Ravna Eira raises this in a poem:

I have no herd

I have no homestead

I do not hunt

Am I a Sámi?

I do have

a Sámi will

a Sámi thought

a Sámi mind

the Sámi tongue.

The poem reflects what makes a person feel Sami and accepted as such. Listed at the start of the first stanza, the herd denotes the importance of reindeer husbandry for acceptance.

An example of the central role that reindeer husbandry has in negotiations of identity arose in discussions preceding the 2017 election for the Saemiedigkie [Sami parliament] in Sweden. In December 2016, one of the political parties in Saemiedigkie filed for the whole electoral roll (including about 7000 people) to be revised, because they calculated that hundreds of people were wrongly enrolled (

Heikki 2016). The request for revision (which was not granted) became a topic during the election campaign, as reported on by the Sami Radio (

Blind 2017;

Hällgren 2016;

Poggats 2016a,

2016b,

2016c,

2016d). One argument that was put forward by advocates of revising the electoral roll was that wrongly listed people, people who were not regarded as Sami, jeopardized the parliament’s legitimacy as a Sami elected body (

Heikki 2016). Parties that opposed the revision, in turn, said that the revision process itself threatened the legitimacy of the parliament, since it might question the work of the electoral board and the parliament (

Poggats 2016b). During an election debate, which was broadcasted by the Sami radio in February 2017, it became clear that political parties most clearly representing ‘reindeer husbandry interests’ favored a revision, whereas the other parties were against it. The chairman of one of the parties in favor of a revision said that ‘In the proposal for a future Sami policy, they [the parties against revision of the electoral roll] want everyone on the electoral roll to be able to join a reindeer husbandry district [My translation].’ (

Poggats 2017). The prospect that the electoral roll could be used as a basis for admission in a reindeer husbandry district seems to have created incentives to restrain electoral enrollment. To understand why reindeer husbandry districts play part here, one must consider the law that most specifically regulates Sami land rights in Swedish Sápmi: the Reindeer husbandry law

1. To exercise land rights that are acknowledged by the law (including use of reindeer grazing areas, hunting and fishing, collecting firewood, building houses, etc.), individuals must be members of a reindeer husbandry district (which refers both to an area and the associated community). The districts’ members themselves review and decide on membership applications, through votes based on numbers of reindeer that members own. Thus, households with the most reindeer have the strongest influence over the district (

Nordin 2007)

2. The vast majority of Sami in Sweden are not members of a reindeer husbandry district. In this context, it should be noted that the parties in favor of revising the electoral roll represent reindeer husbandry districts and family-based companies that already struggle to make ends meet, and they feel pressured by ongoing land-use conflicts and competition over resources (

Sehlin MacNeil 2017). Thus, restricting electoral enrollment can be seen as a way for them to prevent further potential competition and conflict over resources and land in the future.

The debates in the Swedish Saemiedigkie the winter 2016–2017 can be placed in a wider context on electoral enrollment in Sápmi, being vividly discussed in Finland (

Junka-Aikio 2016), as well as within Sámi parlamentáralaš ráđđi (a cooperative body for the Sami parliaments in Norway, Sweden and Finland). In connection to this wider context, researcher Nils Johan Päiviö made a statement in the autumn of 2006, claiming that “swedenized” Sami had taken control of the Saemiedigkie in Sweden. In the statement, he referred to political parties with an interest in “forest life and hunting”. Asked by a reporter from the Sami radio channel what he believed to be “a true Sami”, Päiviö responded ‘A Sami should at least be able to speak Sami and have strong connections. However, there are many Sami who don’t know Sami [language], but still have strong connections to the Sami world, especially in reindeer husbandry there are many who don’t know the language but one would never doubt that they are Sami. [My translation]’ as the interview goes on, he continues to refer to the importance of reindeer husbandry to Saminess in saying that ‘Who should then be permitted to vote? Is it just a meeting where people get to participate without knowing anything substantial about Sápmi. Or should there be real requirements of cultural knowledge and language and strong ties to reindeer husbandry to be Sami? [My translation]’ (

Nutti et al. 2016).

The division between reindeer husbandry and ‘non-reindeer husbandry’ that can be distinguished in the above debates is not only situated in politics and media, but in many Sami contexts in Sweden. A report on racism that was published by the Saemiedigkie in 2018 (

Saemiedigkie 2018) concluded that one of various racist constructs in Sweden that affects Sami was “internal exclusion” within the Sami community (

Saemiedigkie 2018, pp. 5–6). The researchers who drafted the report surveyed Sami people’s views and experiences of racism, and more than a quarter of respondents said that they had been subjected to racism by other Sami (

Saemiedigkie 2018, Appendix A). In this context, the report recounted a story to exemplify a vicious circle where “Sami outside reindeer husbandry are not seen as Sami, and hindered from taking part in Sami traditions because they are not seen as truly Sami” (

Saemiedigkie 2018, p. 35). The issue of internal exclusion has also been reported from northern Norway, where Sami youth with weak place attachment and language skills, multi-ethnic parentage ‘and with a lack of reindeer husbandry affiliation experienced exclusion by community members as not being affirmed as Sami, and therefore reported stressors like anger, resignation, rejection of their Sami origins and poor well-being’ (

Nystad et al. 2017, p. 1).

The debate on electoral enrollment 2016–2017 relates to matters of Sami status, culture, and identity that shape, and are shaped by, how Saminess is constructed and negotiated. Even though there are broadly accepted Sami histories and social spaces in which reindeer husbandry has played, and continues to play, a minor role—Sami tradition, culture, and history are tied to reindeer husbandry, both within and outside the Sami community in Sweden. As my opening story shows, kinship and place can and is used in negotiations of Saminess in Sweden, although these matters (unlike reindeer husbandry) were not referred to as grounds to claim Saminess or Sami status in the referred media discourse.

I believe that considering the role that kinship and place play in Sami culture and identify processes, in past and present, can work settle some of the remnants of 19th century Swedish Sami policy—policies which party dictate the terms and conditions for how Saminess is negotiated in Sweden today. Putting kinship and place up front in a historical study does not tether Sami identity, ethnicity, or culture to time or place—but rather seeks to explore alternate ways to understand Saminess and how it is negotiated, past and present. I also believe that focusing on kinship and place can, and needs to be done, without disregarding or detaching other aspects of Sami identify and culture (such as language or reindeer husbandry). From a Swedish Sami perspective, I hold the division of Sami livelihood, culture, and land-rights into two separate spheres partly responsible for creating unhealthy relationships, as manifested in the form of racism and an exclusionary Saminess. I believe that the rupture needs healing.

1.1. Objectives

In this paper, I explore relationships between kinship, place, and culture in Swedish Sápmi before the first Reindeer grazing law. I focus the study on the area around Gijrejaevrie, in the southern part of Swedish Sápmi, and track kinship relations of the landholders from 1740 to 1870. I then move forwards and connect stories, place names, and narratives to the people and places in and around area, exploring livelihoods and culture beyond reindeer husbandry. I then discuss the role state administration and policy in the late 19th century played in rending Sami livelihood, culture, and land-rights into two (reindeer husbandry-based and other) spheres. By drawing attention to livelihoods and culture beyond reindeer husbandry and considering their bearing on culture and local identity, I aim to re-assess the contentious, and I would argue fabricated, boundary between reindeer herding and non-reindeer herding Sami history and culture.

1.2. Theoretical Concept of People-Place Attachment

The relations between people, place, and cultural belonging are explored here, drawing theoretically on the concept of ‘place attachment’. I understand place as a space of socioecological interactions and place attachment as the emotional, cognitive, social, material, and spiritual relations between people and place. Although I agree with

Norris et al. (

2008, p. 139) that place attachment can be (and studied as) ‘an emotional connection to one’s neighborhood or city, somewhat apart from connections to the specific people who live there’, I do not limit the connections to human emotions. Instead, I apply a wider phenomenological understanding of the concept, regarding place attachment as “part of a broader lived synergy in which the various human and environmental dimensions of place reciprocally impel and sustain each other” (

Seamon 2013, p. 27).

My understanding of place attachment in terms of the relations between people and place also implies that it is not solely driven by the agency of people. Unlike

Scannell and Gifford (

2010), I do not see place as the object of attachment, but rather as a subject in dialogue (

see also: Hernández et al. 2007;

Lewicka 2011). For example, I agree with Scannell and Gifford’s view of place attachment as [partly] a social process whereby individual and group interrelate and influence one another in forming and transforming place attachment. I also fully acknowledge that people can inscribe symbolic meaning to places through common experiences, histories, and/or religion that can be transmitted between generations (

Memmott and Long 2002;

Scannell and Gifford 2010). However, I would like to add that during the process people interact with place. As both

Scannell and Gifford (

2010, p. 2), and

Brown and Perkins (

1992, pp. 279–304) suggest, people become attached to places where they can practice, preserve, and develop their cultures and livelihoods. However, places themselves influence what and how cultures and livelihoods can be practiced, preserved, and developed. Thus, a place is not a passive screen for human projections and place attachment is, in turn, an interaction between people and place.

Building on work by

Scannell and Gifford (

2010), in this paper I connect place to culture, identity, and livelihood. In connection to questions surrounding identity and culture, Scannell and Gifford hold that attachment to place is coupled to a personal sense of self, connected to personal memories, experiences, and events (

Knez 2005, pp. 207–18;

Scannell and Gifford 2010). Thus, being from a certain place creates inward social bonds and distinctiveness from others, and, for some people, places can come to represent who they are (

Scannell and Gifford 2010, p. 3). Here, the concept becomes increasingly blended with the terms ‘place identity’ and ‘belonging’ (

Knez 2005;

Hernández et al. 2007). I do not draw sharp distinctions between these concepts in the paper, but rather regard place identity and belonging as elements of place attachment.

I operationalize the concept by scrutinizing historical archives, exploring storytelling and narratives, as well as place names, primarily searching for information on cultural and livelihood activities, histories, and spiritual practices that are documented in connection to the place Gijrejaevrie.

1.3. Gijrejaevrie—The Place of Study

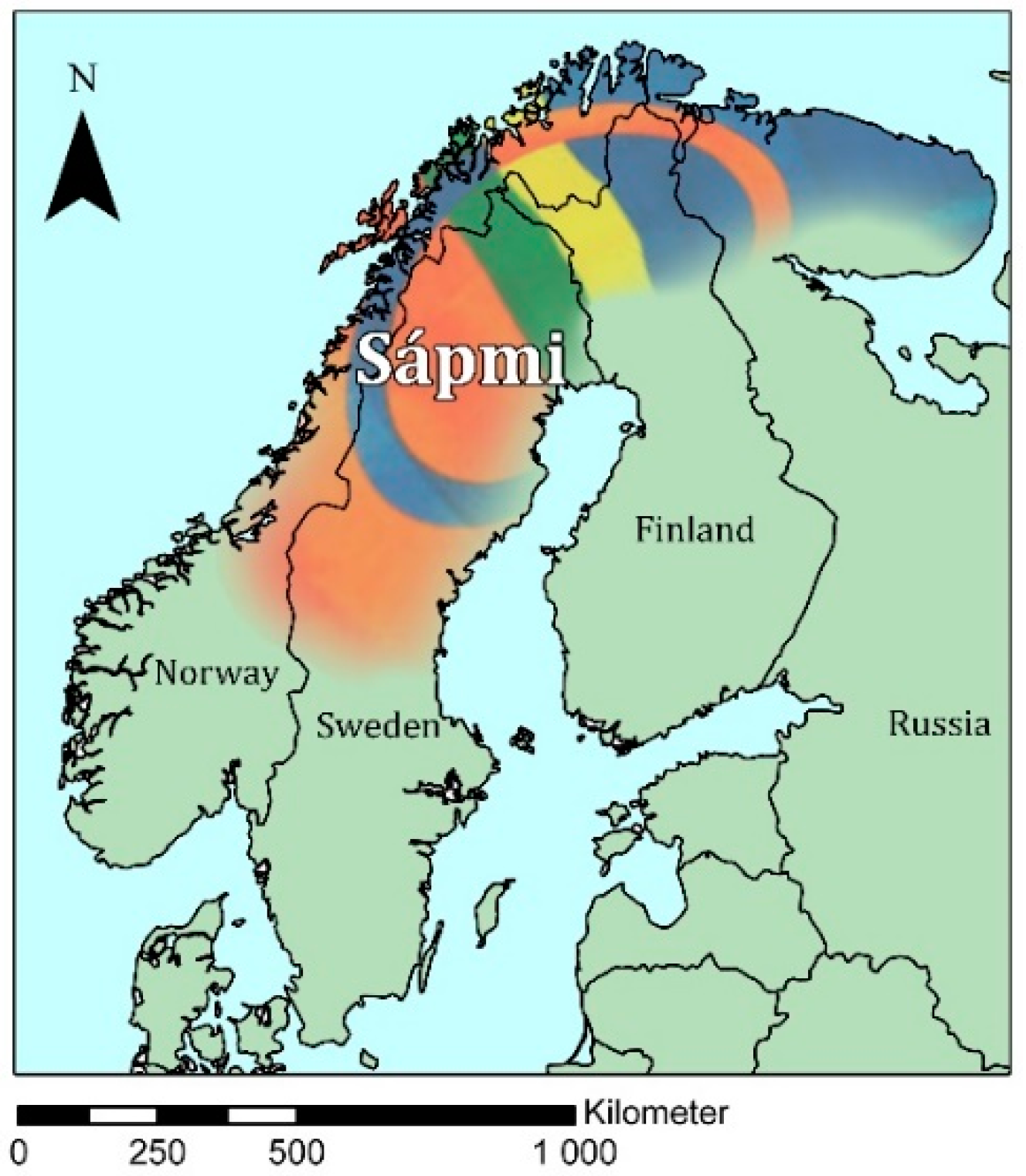

For at least a couple of centuries, Sami communities in the Swedish part of Sápmi (

Figure 1) had distinct land-tenure systems from those of the governing state and surrounding communities (

Korpijaakko-Labba 1994, pp. 321–41;

Josefsson et al. 2010). Sami families and communities were traditionally involved (

inter alia) in fishing, trade, farming, handicrafts, and reindeer husbandry (

Brännlund 2019). The lands were divided into entities held by one or several families in order to regulate social relations and relations between people and places. The lands sustained reindeer husbandry, fishing, hunting, and (later), small-scale farming. For use of these lands, the families paid taxes to the Swedish state (sometimes also to the Norwegian state before the middle of the 18th century). In local Sami contexts, the lands were referred to by their place names, but in Swedish lexicon they are referred to as Sami taxation lands (

Schefferus 1674;

Holmbäck 1922;

Arell 1977;

Korpijaakko-Labba 1994;

Päiviö 2011;

Åhrén 2008). The land that the older community member referred to in my opening story was a ‘Sami taxation land’.

The lands sustained reindeer husbandry, fishing, hunting, and, later on, small scale farming. The political and legislative history of the lands is well documented (

Arell 1977;

Korpijaakko-Labba 1994;

Lundmark 2006). However, the attachment between people and places has received far less attention. We need more knowledge of the roles that lands might have played in individual and collective local history and -identity constructs, before the reindeer grazing laws was passed, in order to re-evaluate and challenge notions of Sami lands as ‘reindeer grazing areas’ and Sami as (purely) ‘reindeer herders’. The place of study is a Sami taxation land called Gijrejaevrie, located within current borders of Vilhelmina north reindeer husbandry district, in the southern part of Sápmi. In the local Sami dialect, the holders of the land were referred to as ‘viesat’ (not spelled according to the 1978 orthography).

It might seem odd to explore place attachment, livelihoods, and culture ‘beyond reindeer husbandry’ in an area that is so heavily influenced by it. There are other areas, for example, forested areas used (inter alia) for reindeer husbandry and areas that are owned or used by settled Sami communities, where other livelihoods and cultural expressions would be more easily detected. However, it increases its suitability for the study, as the aim is to re-assess the supposed boundary between reindeer herding and non-reindeer herding Sami history and culture. Further reasons for selecting the taxation land were that the district members wanted to document the area and its history, and archives covering the investigated time period were available.’.

2. Use of Historical Materials and Narrations

A challenging aspect in studies of Sami history is the absence of Sami voices in the Swedish historical archives. Historical records and material originating from local Sami actors are only available in relation to the latter part of the study period. This poses a risk of merely depicting the perspective and interests of the state, which at that time heavily centered on controlling and administering reindeer husbandry (researchers concerned with the history of subaltern groups often encounter this problem, for a discussion of this in Sami contexts see, for example,

Kuokkanen 2008). In an effort to surmount this issue, I made use of Sami storytelling and place names that that provide a richer history of land-use and people-place attachment. All of material in the study was analyzed critically with respect to context, applying standard source evaluation. The following section offers an overview of central archive materials used and a brief presentation of their setting.

Taxation records for the years 1750 and 1774–1869 were examined in order to study land use in the area and identify landholders and kinship relations (records for the period 1751–1773 and 1819 are missing). The taxation records include the first and family name of every person who was liable for tax, the amounts of tax due and paid, and the name of the taxed land. The sources exhibit good internal consistency; the scripts are of fine quality and good readability (Taxation Record 1750; Taxation Records 1774–1834; Taxation Records 1835–1869).

Church parish records have been examined to ascertain family ties among landholders; this helps to portray kinship ties and how they related to place and land. The holders of Gijrejaevrie were listed by the clergy in catechetical records from 1772, first in Åsele and later in Vilhelmina parish (Parish catechetical record for Åsele 1772–1853; Parish catechetical record for Vilhelmina 1780–1792, 1815–1894). In the registers, priests listed every individual living within their jurisdiction, being arranged by place of residence and household. In addition, every individual’s occupation, legal status, and dates of birth and death were noted.

Court records from Åsele Lappmark judicial district were analyzed to identify livelihoodand cultural practices that were connected and to the land. Court records are important sources of information regarding historical land use, culture, and livelihood. However, the material is vast and not easy to read. In order to access the material, a collection of transcriptions was first examined and in a second phase the original documents were interpreted (Wiklund K.B Avskriftsamling 1645–1845).

Interviews, narrations, and stories conducted and collected in the area by Torkel Tomasson in the summer of 1917 were analyzed to investigate land use, livelihood, and cultural practices during the latter part of the study period. Tomasson was a Sami politician, writer, and founder of

Samelfolket (the Sami people’s journal). In the summer of 1917, he conducted 22 interviews in southern Sápmi and collected stories about livelihood customs, reindeer husbandry, and belief systems (Reindeer herd migration into Norway by Vilhelmina and Vapsten Sami written by Torkel Tomasson;

Tomasson 1988).

3. Intergenerational Connections between People and Place

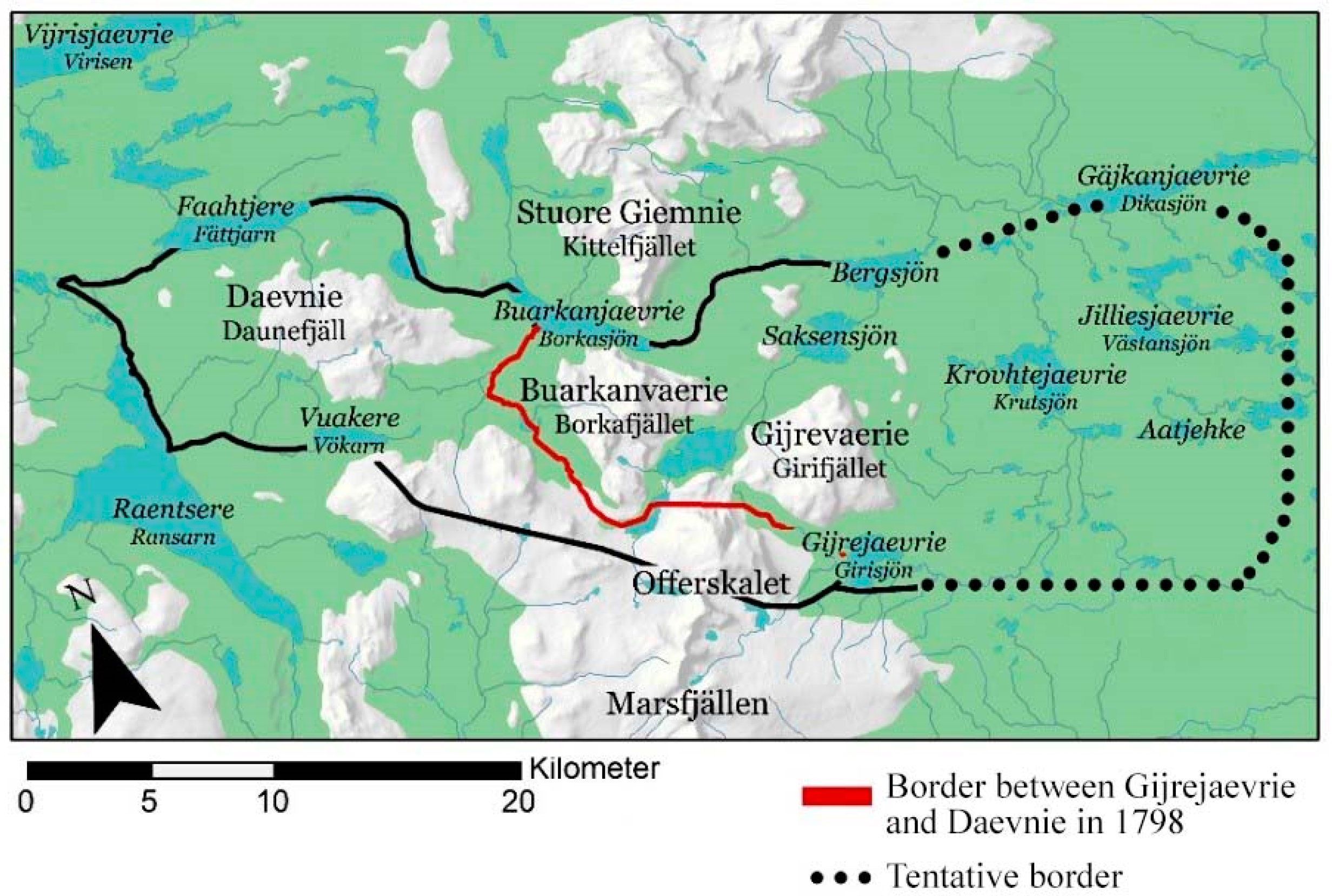

The place name Gijrejaevrie derives from the south Sami words for spring and lake, which indicates the importance of the lake and its use, particularly during spring and early summer. In Gijrejaevrie (

Figure 2), an arena for social interaction, the main dwelling of the landholding family was on a ridge called Koksikkammen. Reindeer migration routes that were used by herders in the area crossed the outskirts of the land. The land was also part of the calving ground during early summer (Inquiry of Sami Issues in Västerbotten County 1912;

Pettersson 1979;

Qvigstad and Wiklund 1912; State Report on Untaxed Properties Year 1914).

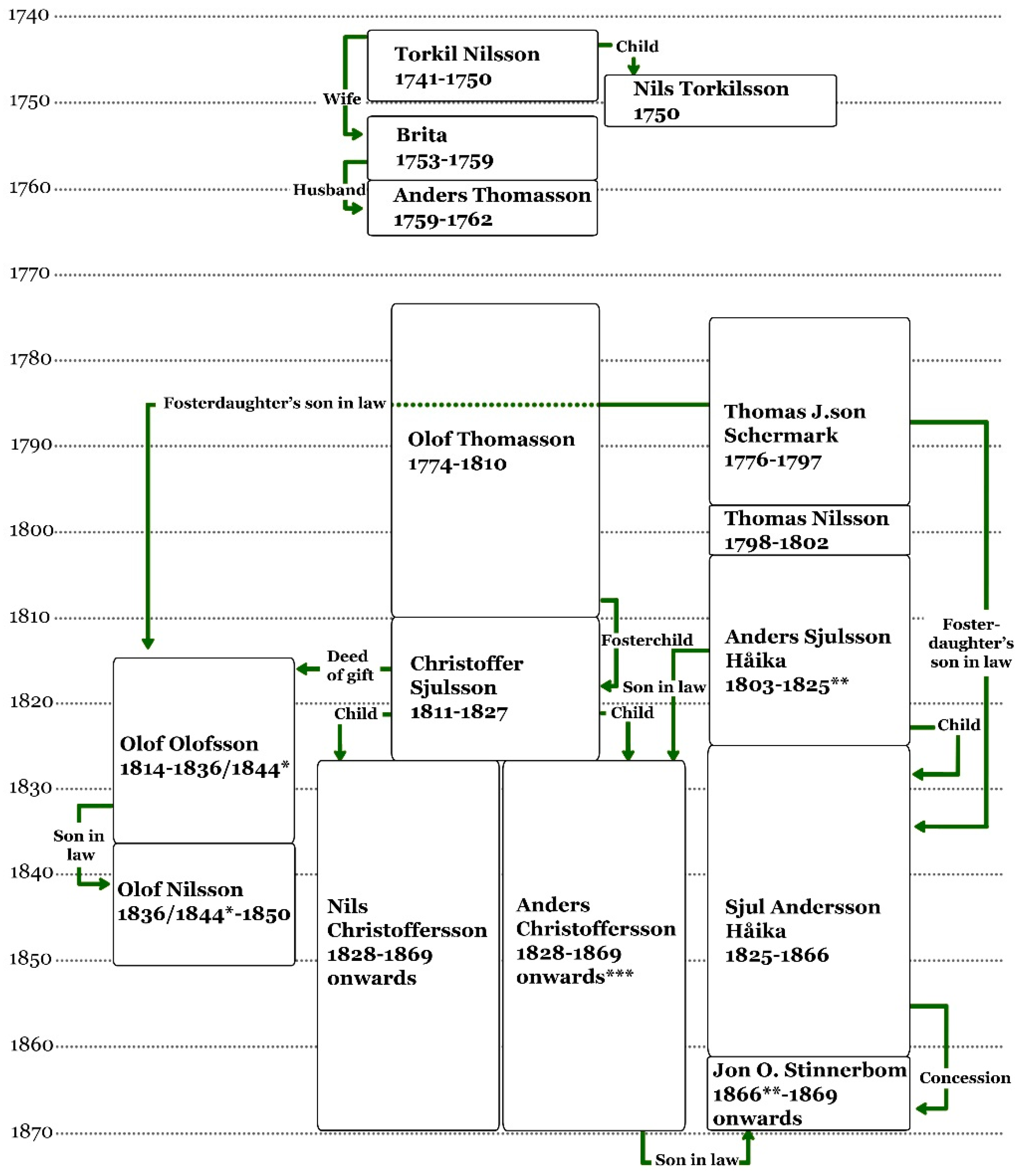

With the help of taxation records, church records, and county administrative archives, landholders of Gijrejaevrie taxation land have been identified over a period of 130 years (1740–1870). As shown in

Figure 3, holders of the land were all strongly related throughout this period. The taxation records only noted the males’ or widowed women’s names in the tax papers (although land use and land title were family matters). This reflects county administrators’ view of land title and taxation as being primarily a male domain and it echoes previous findings that Swedish administrators’ understanding of Sami culture and reindeer husbandry was (and is) male gendered (

Amft 1998, pp. 69–80;

Ledman 2012, pp. 115, 148–53). Nevertheless, we can see that many women carried land titles over time. In the figure, all linkages display this where a son-in-law was registered as a new taxpayer.

As also shown in

Figure 3, title transfers occurred when a landholder passed away and the transfers seem to have followed a pattern of inheritance, as the land was generally passed from one generation to the next, and only occasionallypassed to people outside the immediate family when the landholders had no biological children. In the sole exception during the study period, by deed of gift Christoffer Sjulsson gave Olof Olofsson right to a third of the land, a part that was later returned to the Sjulsson family. However, Olofsson was not a stranger to the land, because he was linked to the former holders by marriage.

The strong intergenerational connections between people in Gijrejaevrie signal people-place attachment in the form of cognitive (knowledge the land) and material (use of resources) relations between people and place. Moreover, people used the place name (and names of other Sami taxation lands) not only in the context of tax payments, but also as an intercultural identifier (

Tomasson 1988). This shows that Gijrejaevrie represented who people were and functioned as a node in culture and local identity processes. Genealogical origin and relation to land or place are commonly part of, and negotiated, in ethnic discourses (

Roosens 1990, p. 160). In the context of this study, I would say that these aspects were clear in intercultural discourses.

Reconnecting with the understanding of place attachment as an interaction between people and place, the individuals of Gijrejaevrie are regarded as having not only a personal genealogy (as descendants of people), but also had a genealogy of place. This was a genealogy of place that was attached to them that they needed to relate to, regardless of their recognition of it and irrespective of their emotional relations to the place. During the study period, holding a taxation land and possession of appropriate documents acknowledging this right secured a family’s rights to live on and off the land, to fish and hunt, take material for handicraft and houses, and use it for herding reindeer—rights that many Sami today lack. In the context of my opening story, I believe that intergenerational connections between people and place, together with Sami taxation lands’ strong associations with rights, help to explain the roles that are played by connections between genealogy and taxation lands in identity processes and discussions on land-rights in Swedish Sápmi today.

The material, albeit interesting, conveys people-place relations in the context of state control and administrative interest in reindeer husbandry. As discussed in

Section 2, considerable material on “Sami issues” is tied to reindeer husbandry, but there are other materials, stories, tales, and interviews that convey a richer history of land-use and people-place attachment.

5. Reindeer Husbandry above Place: National Policies on “Sami Issues”

In Swedish Sápmi, colonization (the process of territorial, economic, and socio-political conquest and control) was coupled with a national process of distribution and separation of estate, in which traditional Sami lands were separated from state land.

Stenman (

1983, pp. 65–68, 279), who studied the procedure in the county Västerbotten, argues that the state wanted “unused” property to be further “divided into a new homestead, if there were opportunities for colonization”. The formal process of distribution and separation of estate started with legislation passed in 1873 in the inner parts of Västerbotten, where Gijrejaevrie was located. The legislation stated that Sami had a continued right to “use traditional areas for reindeer husbandry”, but it did not consider reindeer husbandry, hunting, or fishing grounds for land claims. Neither were genealogical connections nor attachment to the land

4. Under the new law, previous rights that the families had to manage Gijrejaevrie or protect the land from other users were bypassed.

The national process of distribution and separation of estate coincided with an administrative change in state policy concerning the taxation lands (

Korpijaakko-Labba 1994;

Lundmark 2006;

Päiviö 2011). The first incident that demonstrated this change in Gijrejaevrie regards an application from Christoffer Sjulsson and Maria Nilsdotter to take over the land from Sjulsson’s foster father (Concession and Title Documents, May 6th 1809). According to the new order, the family was obliged to apply for a title deed from the county administration instead of the court. Their application, which was granted, included a document stating that the foster father had granted the applicants his land title. Sixteen years later, the county administration processed another application; Olof Olofsson applied for a title citing a deed of gift signed by the current holder, Christoffer Sjulsson. This time the county administration also granted the application, but attached a caveat, granting Olofsson one-third of the land “for as long as he needed it for his own reindeer herds” (Concession and Title Documents, July 4th 1825). In the eyes of the administration, the taxation land was now primarily reindeer grazing ground, not Sami land.

The confinement of Sami land rights, cultural life, and livelihoods to reindeer husbandry also influenced the legislative framework regulating Sami land rights during the latter part of the 19th century (

Lantto 2000, pp. 94–114;

Lundmark 2006;

Päiviö 2011). Reindeer Grazing Acts, which were passed in 1886, 1898, and 1928, established a discourse in which Sami rights and the understanding of Sami culture were strongly confined to reindeer husbandry. A key element of this discourse was that ‘pure’ Sami people lived far away in the mountains, in traditional temporary settlements, surviving on reindeer husbandry alone. All forms of combined livelihoods, including fishing, hunting, and/or small-scale farming, were seen as inauthentic hybrid lifestyles (

Brännlund 2019;

Mörkenstam 1999, pp. 79–107;

Thomasson 2002).

Records of County administrative level indicate that, although state authorities wanted to increase agriculture, they did not want Sami to turn their own taxation lands into agricultural properties. There were probably multiple reasons for this. The taxation lands were extensive (commonly covering areas of 1500 hectares during the early phase of the study period) and they covered almost the entire northern Swedish mountain range. Thus, recognizing these lands as agricultural properties would have allocated extensive parts of the traditional Sami area to a few Sami families. Not all Sami families held a taxation land and their ability to use the land would probably have decreased under the legislative landscape of the time. From a financial perspective, it would have strongly affected the state’s ability to withdraw resources from the area (which the state considered itself to possess). Furthermore, acknowledging the lands as private property would have decreased state control over the area. Finally, there was an element of racism that was embedded in the state’s reluctance to promote Sami agriculture. Agriculture was seen as a breakdown of “traditional Sami nomadism” and settlement was understood as a hindrance to continuation of reindeer husbandry and, by extension, Sami culture (

SCB 1909; Sami Committee of 1919, vol. I).

In addition to the portrayal of Sami as nomadic reindeer herders was a notion of Sami as ‘homeless’. The Sami Bailiff in Norrbotten County, Frans Forsström, challenges this notion in a letter to the provincial court in 1892:

Up until now people believed that the Sami would be indifferent to the places he migrated to or lived in, just as long as he found grazing for his reindeer and the reindeer in other respects were content. However, many circumstances have convinced me that the Sami are just as fond of their fatherland as the resident populations are of theirs, and that they are very reluctant to leave it.

(Sami Bailiff in Norrbottens Northern District Yearly Report of 1890)

The ideas of Sami people as homeless nomads roaming around in the mountains, as indicated by the above quotation of the Sami Bailiff, implies that Sami lacked connection or attachment to place. This idea starkly conflicts with findings of this study, as the taxation and parish records clearly show that families had strong multi-generational and multi-dimensional commitment to places.

6. Concluding Summary

By confining Sami land title to reindeer husbandry in the late 19th century the state they endorsed a notion of Sami as reindeer herders, a notion that continues to be reproduced, both within and outside the Sami community. In this study place attachment have open up new readings of history and challenged this notion by persuading us to see beyond static, predefined categories of livelihood and ethnicity.

The historical exploration of place attachment have merged reindeer and non-reindeer herding Sami history and displayed that people had a range of livelihoods, cultural practices, and trades—in place. The Sami lands were not used, or perceived, solely as grazing areas for reindeer. In these people-place interactions, bonds of attachment between people and place manifested themselves in various ways. In ongoing dialectical process, places had resources setting the stage for people’s cultural expressions and livelihoods (such as handicraft, fishing, and reindeer husbandry), which in turn, imprinted in place both physically (such as bone disposal sites, sacred sites, de-barked trees, and farmsteads) and socially (naming of places, storytelling, and place identity).

The results show connections between people, place, and cultural belonging that were not reliant on reindeer husbandry, clearing space for local Sami identity processes ‘being’ and ‘becoming’ something else than reindeer herders. However, this was restricted by the confinement of Sami land title to reindeer husbandry and the notion of Sami as reindeer herders—restricting families and individuals from developing their culture and livelihoods as Sami, independent of reindeer husbandry. Moreover, these constructs were not restricted to a discourse of Sami or land, but they became anchored to the land by the legal framework regarding Sami land rights in Sweden. As a result, many people, who today identify as Sami experience exclusion both in terms of rights and identity. It is a cause of conflicts, which, even though they might be centered on land rights and land use, sometimes are experienced or manifested in the form of racism or exclusionary Saminess.

I believe that the study primarily provides new insight into our history where reindeer husbandry and “non- reindeer husbandry” is allowed to mend. This contributes to a wider understanding of historical Sami culture, way of life, and local identities, which is fluid and changes over time. Knowledge I believe can help us to better comprehend the role that ancestry and place have for people’s identity processes today. However, what bearing does this history have on contemporary identity processes and land rights in Swedish Sápmi?

On one hand, history can open up new ways of thinking about culture, place, and belonging. Thus, this study might support people in the process of rediscovering, claiming, or reclaiming Saminess. However, as contemporary Sami identity is constructed around ‘a real connection to, and a sense of belonging […] that cannot be artificially reconstructed by exploring one’s family tree or taxation records back to the 1600s or 1700s.’ (

Junka-Aikio 2016, p. 215) Thus, (re)discovering Sami heritage does not equal becoming Sami. Moreover, using historical examples in contemporary negotiations of identity is problematic. As Hall nicely puts it, ‘cultural identities come from somewhere, have histories. But, like everything which is historical, they undergo constant transformation’ (

Hall 1994, p. 394). Thus, calling for history in negotiations of identity risks reproducing an assumption that identities are tethered to a time and a place—that they were authentic in the past (but maybe not now). This, in turn, can hamper contemporary identity processes, including the imagining of future and moving (in and out of) place.

Notwithstanding these objections, just as ‘identities are the names we give to the different ways we are positioned by, and position ourselves within, the narratives of the past’ (

Hall 1994, p. 394). Sami today call on history, their genealogy of kinship, and place to signal Sami belonging. As my opening story shows, people continue to evoke their connections to place, regardless of livelihood. Depending on individual circumstances, experiences, and context, the meaning that the connections is given and how it is expressed differ, but place attachment has a role in Sami identity constructs today, partly due to the history portrayed in this paper. In this context, the results of the study do have implications for the way that we understand Saminess today, because it offers a narrative of the past, a place people can positions themselves within—regardless of whether they (re)discovered their Sami heritage in taxation records or always known about it, are part of a reindeer herding district or are not.