1. CHamoru People

The

CHamoru (Chamorro) people are of Austronesian origins that settled in the Mariana Islands at least over 3000 years ago (

Cunningham 1992). After more than 2500 years of isolation from the outside world the

CHamoru people eventually developed rare mutations of their DNA making them a unique population among other races (

Vilar et al. 2012). Following that extended period of isolation and independence, the people of the Mariana Islands became subjected to a variety of colonial powers for over the next 350 years. While the people and islands are first recorded in 1521 by the Spaniards, colonial imposition began in 1668 with the arrival of Spanish Jesuits and Army that lasted until 1898 (

Garcia 2004). As a result of the Spanish-American war, the

CHamoru people of the Mariana Islands were and continue to remain victims of partition. For the

CHamoru people of Guam, they were under the rule and possession of the United States from 1898–1941, Japan 1941–1944 (World War II), and then back to the U.S. from 1944–present (

Rogers 1995). For the

CHamoru people residing in the rest of the Mariana Islands, they were under the possession and rule of Germany from 1899–1914, Japan 1914–1944 (World War I and II), 1944–1975 administered by the U.S. a United Nations trusteeship, and by 1975 became the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, a territory of the U.S. (

Farrell 2011).

Indeed, the “Chamorro identity is inextricably intertwined in a complex colonial history” (

Perez 2005, p. 589). Many challenges to

CHamoru genealogy are introduced by it. Some examples include the replacement of indigenous first names with Christian names upon baptismal, names recorded under Spanish traditions, and a mandate to record names using the American convention that was decreed by a U.S. Naval Governor in 1920 (

Punzalan 2009). Perhaps one of the biggest and current genealogy challenges now facing the

CHamoru people are those of the diaspora.

Perez (

2005) notes that a

CHamoru exodus has been historically evident since Guam citizens gained U.S. citizenship in 1950. Many

CHamoru people left their homes to join the military while others for opportunity or some other change. For Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI) citizens they were granted U.S. citizenship in 1986 through a covenant with the U.S.

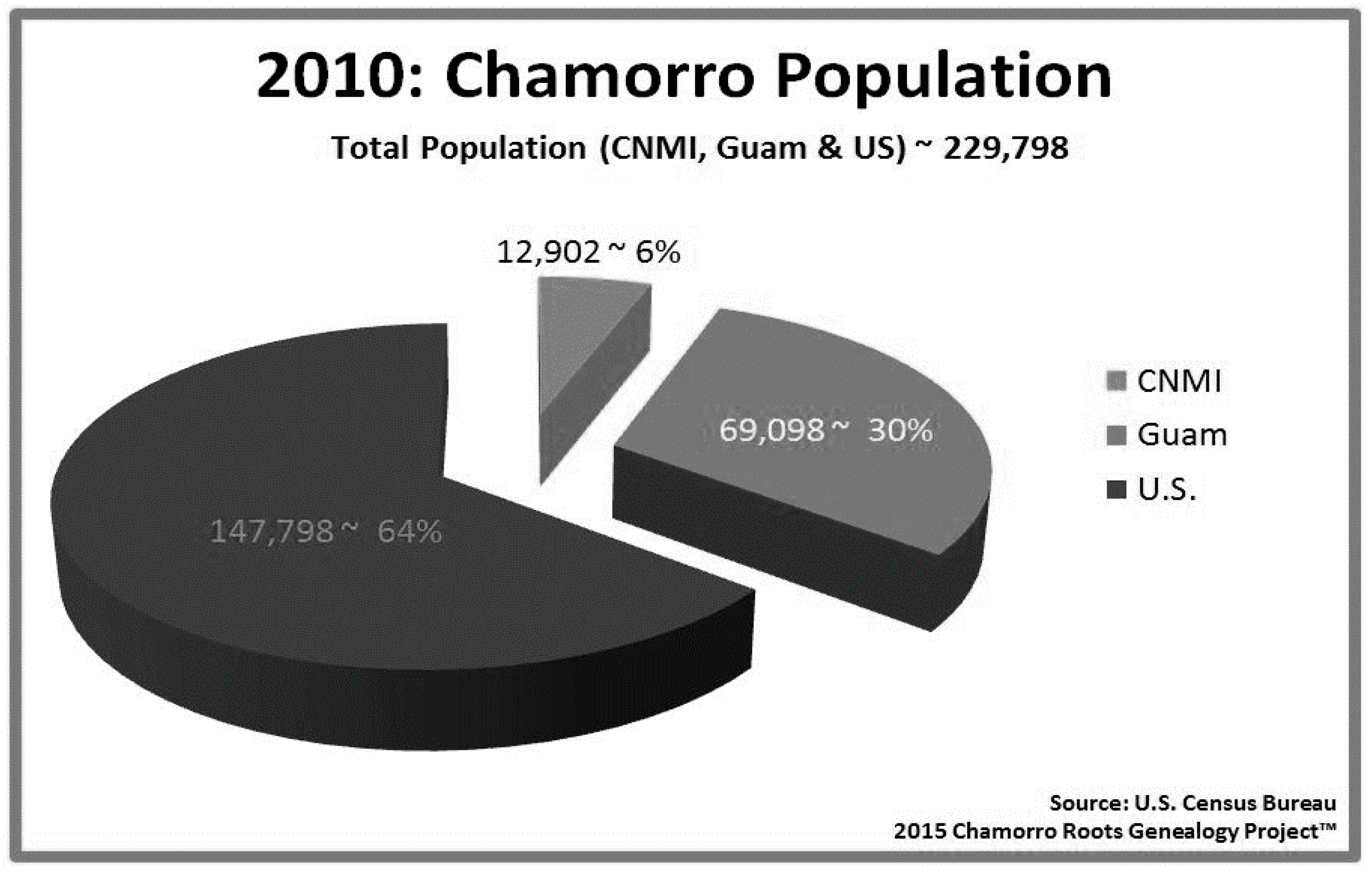

Later in this paper, you will find that more than the majority of the entire CHamoru population reside in the U.S. as opposed to their native Mariana Islands. In family alone, my sons are fourth generation military servants to the U.S. My parents and grandparents have taught me in so many ways that no matter where we are at in this world, family is a significant part of the CHamoru culture. Therefore, the recording and preserving of CHamoru genealogy is also paramount to maintaining and demonstrating the unique identity and heritage of the CHamoru people.

2. The Chamorro Roots Genealogy Project

Since 2003, I have been passionately cultivating the Chamorro Roots Genealogy Project (Punzalan n.d.). What initially started out as a family roots project, eventually evolved into a community-wide project for the CHamoru people. This Project is a token of my chenchule’ (reciprocal contribution) to our CHamoru people that is primarily funded at my own personal expense. Other funding sources include chenchule’ from individuals who believe in or have benefited from the Project. Proceeds from information created and published from this Project have also helped to offset costs.

I must admit that I have no genealogy training or academic background; however, during the course of my personal family genealogy research I encountered gaps of information, misinformation and the lack of on-line genealogy resources regarding the

CHamoru people. There were only two websites where I was able find some information, which were the Familian Chamorro Genealogy Database Index (

Micronesian Area Research Center n.d.) and

Ancestry (

n.d.). Both were very limited in scope and information. These issues became more and more frustrating as I tried to progress with my research. So I finally decided to become part of the solution by trying to fill those gaps by creating the Chamorro Roots Genealogy Project.

With the lack of accessible resources, I envisioned the Chamorro Roots Genealogy Project to become the premiere portal of CHamoru genealogy, where the CHamoru people, local and abroad, can have access to a centralized repository of genealogy information. The initial marketing and outreach establishment of the Chamorro Roots Genealogy Project was by word of mouth. Today, with the use of the current technological tools available, the outreach and effect has become incredibly overwhelming.

I am pretty much a one-person operation when it comes to the technological administration and demonstration of the Project. This includes administering and developing the website, performing some minor custom coding and ensuring that the various independent software applications that make up the Project website are compatible and woven correctly in order for each to work together. This Project has many collaborators and contributors, but I remain the principal investigator of the Project who performs most of the research, data gathering, publications and presentations on the Project. With all the data mining from the information gathered, the Project has produced a variety of resources, which are highlighted later in this paper.

I often wonder why this Project seems to take much of my undivided attention and passion. I spend at least six to eight hours after my normal job and then another twelve to fourteen hours on the weekends working on this Project. Perhaps the most compelling and fulfilling reason seems to be because of the people reaching out to me on social media for their desire to learn more, and to reconnect with their roots and heritage. When I am able to provide them with some feedback and information their praise and gratitude reminds me that I am doing something very productive and that is something much bigger and greater beyond any one individual. This encouragement also reminds me of what Dr. Robert A.

Underwood (

1997), a well-known

CHamoru educator, who also served several terms as a U.S. Congressional Delegate for Guam, wrote:

“We fail to be actors in our own history and, as a consequence, we hand down the lesson that we cannot be actors in our future. History becomes painful not because there was pain and loss, but because our agency as a people has been denied. History is about telling a story for understanding so that we can do two things today. First, we can understand the environment we live in and the underpinnings of institutional and social behavior. Second we can then behave in the present and plan for the future from a position of strength … The failure to understand history, or to assume that only one rendering of its dimensions is possible, is tantamount to oppression. Without the knowledge of the past or access to its riches, we can be victimized by those who claim to know it and by those who wish to manipulate its lessons...we must participate in the historical project as a society. All of us must acquire the habit of history from a common basis. No particular advantage is gained and much harm occurs when only a few acquire the habit of history. When inaccurate history goes unchallenged and a lack of critical thinking occurs, others are allowed to tell us which parts of history are important and which are not.”

(pp. 4–5)

I initially started the Project’s website using The Next Generation of Genealogy Sitebuilding application (

Lythgoe n.d.). This remains the cornerstone of the Project which houses the database. It allows for registered users to make recommendations to add or correct individual or family information as well submit documents and photos. However, it did not completely offer some key features found in an open source content management system (CMS) that I needed to collaborate with people, such as a discussion board or internal messaging.

The next thing I added to enhance the website was a CMS called PHP-Nuke (

Burzi n.d.). After a while, that too did not bode well for me in what I was trying to achieve so I switched to Joomla (

Open Source Matters Inc. n.d.). Although Joomla had so many available features I soon found out that all CMS platforms were vulnerable to spamming, hacks and other security concerns. The most common attacks I experienced were targeted at discussion boards and places within the website that offered the public or registered users some space for comment. This was a steep learning curve for me to grasp and mitigate. Fortunately, I have continued to monitor and manage those vulnerabilities with more website add-ons that protect and secure the data and website.

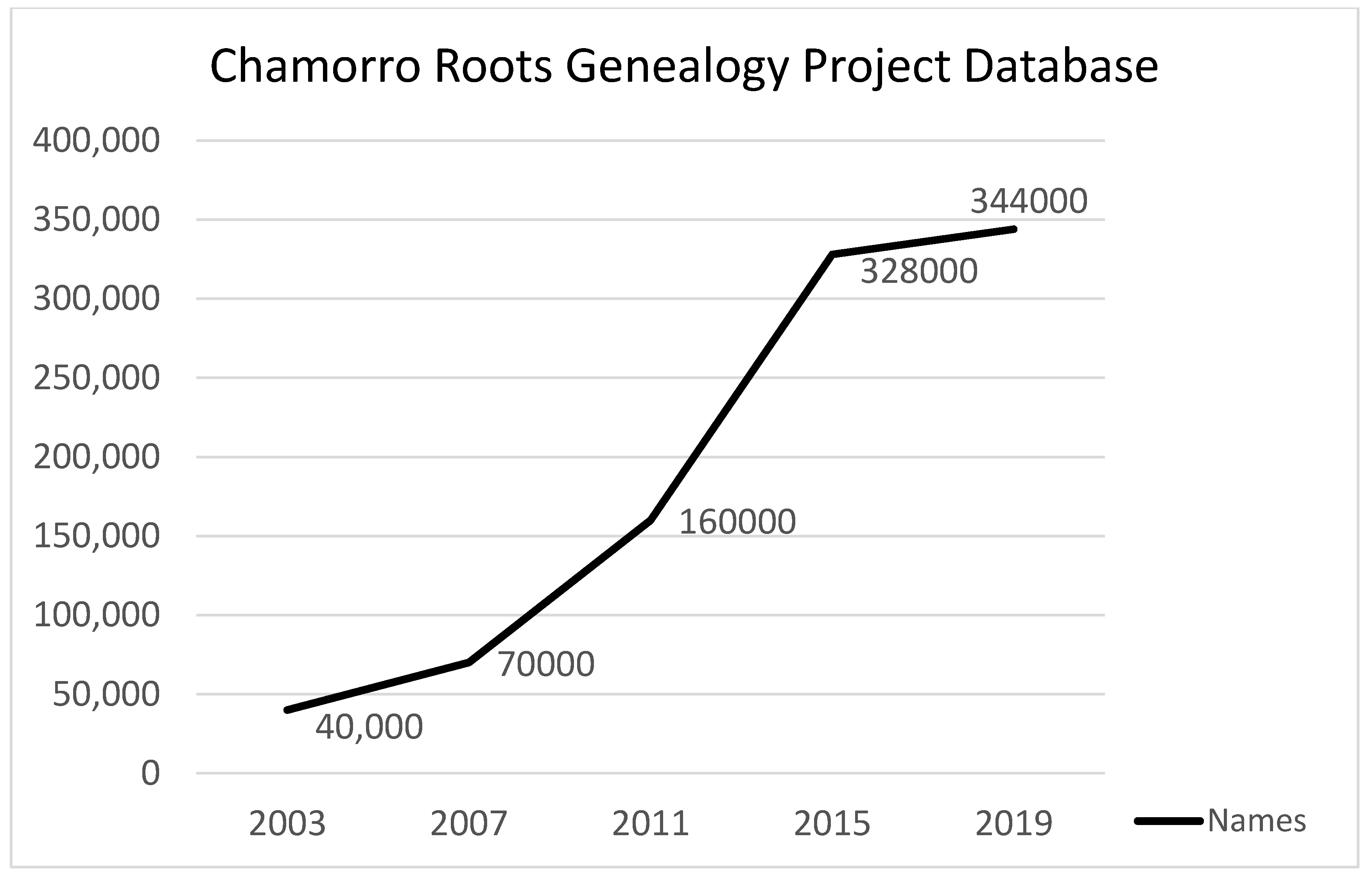

To some extent, the growth in the Project’s database correlates with some types of key projects pursued. As depicted in

Figure 1, with the exception of 2019, after every four years, the number of names in the database doubled. Typically, the bulk of the growth stems from being able to capture existing data first onto a spreadsheet that I was able to secure from other sources on the internet and then convert and transpose the spreadsheet data into GEDCOM file format and then add the new tables to the Project’s database.

The most productive four-year period of database entries occurred between 2011 and 2015 in which the database grew by over 128,000 names. Leveraging technology, networking and social media were significant factors of this spike. During this period the Project was highly engaged on variety of collaborative projects that involved a major undertaking of transcribing and indexing Census documents: The 1727 and 1758 Census of the Mariana Islands; and the US Federal population census of 1920 and 1930 for Guam were important historical sources sued in this Project. Also occurring during this extremely productive period were pilot projects (later discussed in this paper) that yielded more data and reports. In 2015, I was also blessed with being selected as a Guam Delegate from the CHamoru diaspora for specializing in CHamoru genealogy. At the 2016 Festival of the Pacific Arts, I presented a CHamoru Diaspora Seminar and conducted a CHamoru genealogy workshop.

3. Leveraging Social Media

My efforts to leverage social media for the Project produced additional data. I moderate a couple of Facebook™ (FB) group pages. In addition, I have been added by FB Friends to at least 33 family groups; each group having an interest in their genealogy and often seek my help. So I not only communicate and receive inquiries through the Project’s website, but also through social networks.

In 2009, I started my personal account with FB. As I began to post comments and images related to CHamoru history and genealogy, the interest slowly but surely gained some momentum. I then joined the FB group Todu I Familian Chamorro (All Chamorro Families) and started posting topics there as well. As I garnered more interest from people, Ms. Lou Torre Montez, a member of that group suggested I start another group. I not only took her up on that challenge, but only under the condition that she would help me administer and moderate the group.

In 2011, I officially established the Chamorro Roots ~

Hale’ CHamoru FB group. Naturally, the primary topics were focused on

CHamoru genealogy and history. I was able to share many things I had researched and learned during this special journey of mine developing the Project. As a result of this group we were able to publish two key reports based on group members contributing to information we solicited from them (

Punzalan 2014a,

2014b). These reports are linked to

CHamoru customs regarding nicknames and are the pilot projects I referred to earlier. The

CHamoru people have a practice of providing people and families with nicknames rather than using first names or just family clan names. These, in some cases, start out as a nickname for an individual, but eventually the whole family is tagged with the nickname as a unit. These nicknames are very helpful towards pinpointing and establishing a person’s genealogical connection.

When I started these pilot projects attached to FB, I was not quite sure how the results would turn out. Initially, I thought about setting some inclusion and exclusion criteria for submission entries, but then realized that I might not capture the essence of people’s contributions and effort. Also, it may have precluded some frequency data that might somehow be helpful in the future to distinguish between common, unique or even spin-off nicknames that I am tracking.

The online work also provided a way to connect with people to share their experiences and knowledge so any contribution was better than none. It was also a great way to recognize people that contribute and have become a part, and source, of a community with a common interest which we recognized by publishing these results. Hopefully, this effort will continue to spark interest and motivate others to contribute their knowledge and experience.

4. Significance of Nicknames

Like many other cultures there are certain names in

CHamoru communities that are very common in numbers it becomes difficult to determine which Maria or Jose Cruz may be the subjects of discussion. There is very little published material in the mainstream on

CHamoru nicknames from the Mariana Islands. The two most notable are from Laura

Thompson (

1932),

Archaeology of the Mariana Islands, and Anthony

“Malia”

Ramirez (

1984)

Chamorro Nicknames, republished in Guampedia.com. While Thompson’s work on this topic primarily comes from Gertrude “

Trudes Alimån” Hornbostel (

Flores n.d.), and is somewhat brief, Ramirez provides an excellent baseline description of what tends to comprise a

CHamoru family clan. Family clan names are a way of identifying specific families tied to a larger family tree.

According to Ramirez, family nicknames tend to be derived from a reference of at least one of ten categories. For example, see

Table 1:

Louis Claud

Freycinet (

2003), during his 1819 visit to the Mariana Islands, recorded that some of the native children were given names based on the talents or personal qualities of their father, or named after fruit, plants, and other things. All else considered, the ancient people of the Mariana Islands only had a first name. Some scholars are convinced that the names of these people were dynamic. In other words, their names were not static. At some point, depending on the circumstances, the name may have changed as a result of an event that may have occurred. In the case of a family clan name, such an event helps to frame a time point and a specific family within a larger clan. Therefore, the first effort made on FB was to add to the knowledgebase of

CHamoru family clan names.

5. CHamoru Family Clan Name Resource

On 24 June 2012, I issued a call for family clan name submissions that was fielded strictly on FB after being inspired by Joseph Hocog

Aldan (

n.d.) collection of family clan names from Rota, Tinian and Sa’ipan. This call, with the assistance of Ms. Montez on several

CHamoru-related FB groups, in addition to the data from Aldan’s work, the published work of Ramirez and Thompson, combined with the data from the Chamorro Roots Genealogy Project were all incorporated within the report,

Nå’an Manggåfan Taotao Håya, Chamorro Family Clan Names. It was finally compiled and released on 8 July 2014 (

Punzalan 2014b). We received positive feedback from our FB group members on the report and they were elated to see that they were cited as sources for their entries.

During the call, we also asked FB participants that if they knew the meaning or history of the family clan name to provide that information. While some contributors were able to provide the meaning (CHamoru to English translation), very few knew the history of how the family clan name came about.

The effort and call for family clan names produced a total of 5760 entries (

Table 2).

The family clan name report does not assert that all 5760 clan names were unique. In fact, the spelling variation of CHamoru family clan names is somewhat problematic and can be a challenge for those unfamiliar with the native language and orthography. These variations are a result of the orthography from the colonial occupation and administration of the Mariana Islands by the Spanish, Germans, Japanese and United States Americans over the last 400 years. While spelling variations remain a challenge to exact a number, the data seems to suggest that there are at least 1100 unique family clan names listed in the Appendix of the Report.

First Name—Nickname Resource

After obtaining some preliminary research on family clan names, it further fueled my interest to conduct a second call of interest regarding nicknames for first names. In one of the most widely used Chamorro-English dictionary books, there are many examples of nicknames that were supplied by Rufino Tudela of Sa’ipan and included (

Topping et al. 1975). The purpose for including the nicknames was to demonstrate that most

CHamoru nicknames tend to evolve from using the latter part of a given name. Granted, there are exceptions, however, this is worth being mindful of since some

CHamoru family clan names are derivatives of first names. This may also further explain (requires more research and data analysis) how some clan names today may be actual derivatives of ancient clan names.

Påle’ Eric

Forbes (

2011), a

CHamoru Historian and Genealogist, also affirms this nickname practice. For example (

Table 3):

Therefore, the other report from our FB group that was produced is the

Chamorro Roots ~ Hale’ CHamoru First Name Nickname Dictionary (First Annual Report), published on 9 April 2014 (

Punzalan 2014a). The call for submissions was simple. We asked people to provide us with a first name and nickname associated for that person that they or their family uses. However, this time we decided to keep it manageable by limiting the call strictly to the Chamorro Roots ~

Hale’ CHamoru FB group. Again, I was not sure how this would pan out because, not every member in a group is engaged in discussions.

While the call was simple and made only on one FB group post, it still required constant monitoring and ensuring that the call remained at the top of postings and not lost in a conglomerate of discussions. We learned quickly to add a photo to the post, because it was easier for us to quickly locate the photo than a discussion. This should not be an issue these days because FB now allow group administrators to “Pin” certain posts that remain at the top of the discussion. Also, FB at the time did not have a polling option.

The data collected from that pilot project lasted for one year from 4 April 2013 to 3 April 2014. From this effort there were 655 entries that came from a little less than one percent of the 4442 group members. We found that there were 255 unique first name entries and 515 unique nickname entries, which demonstrated that one first name may have several nicknames associated with it. I have yet to initiate a subsequent call for any succeeding report to this particular effort.

6. Census Transcriptions and Index—Resources

Through a combination of certain website features, FB groups and email exchanges, I was able to lead and facilitate the collaborative efforts to transcribe and proof-read census records that were transcribed, indexed and then published as additional genealogy tools of reference. The Project’s website housed the census images and transcriptions for collaborators to sign-in, view, and download the transcriptions for proofreading. Once the proofreader completed each census page, an email was sent back to me either confirming the transcription or identifying typographical errors for correction. Through these technological tools and collaborative efforts the Chamorro Roots Genealogy Project self-published the following resources:

1920 Population Census of Guam—Transcribed (

Punzalan 2012a), in print (560 pages) and eBook copy. The print copy is globally available, while the eBook copy is exclusively accessible only at the Project’s website.

Index: 1920 Population Census of Guam—Transcribed (

Punzalan 2012b). This a companion copy and quick reference index to the former. Initially, this was available only as an eBook, but by numerous requests, print copies have been globally available since 2018.

1930 Population Census of Guam—Transcribed (

Punzalan 2014c), in print (796 pages). Like the 1920 census transcription, the print copy for this is globally available, while the eBook copy is exclusively accessible only at the Project’s website.

Index: 1930 Population Census of Guam—Transcribed (

Punzalan 2014d). This too is a companion copy and quick reference index. Likewise, it was available only as an eBook, but by numerous requests, print copies have been globally available since 2018.

Once this data was transcribed it became a much more meaningful set of tools for CHamoru genealogy. We now have specific datasets that can be analyzed and viewed more closely from a cultural and genealogical lens of history.

Census Observations

One of the first things that stand out when reviewing the census documents and data of the 1727 and 1758 is that Spanish colonization and conversion of the

CHamoru natives to Catholicism is apparent within the transition of indigenous native names to Hispanic style. Prior to contact, the indigenous people only had one name. It was not until they were baptized, the Jesuits renamed them with a Christian name and their indigenous name became their surname. In the transcription of those census documents, the majority of indigenous immediate family units had different surnames (

Levesque 2000a,

2000b).

Initially, when we transcribed the 1920 Census we had a few challenges in reconciling the population numbers. The Census Bureau reported an official count or 13,275, which took a while to match (

NARA 1920). In addition, one segment population, from the Yigo Barrio, consisting of 107 people were entirely illegible so there was even a challenge to reconcile age, race, and gender population counts. However, from the data we were able to discern some interesting facts such as: identifying the oldest female and male, top ten most common female and male first names, top ten most common surnames, the enumeration and potential cause of people being recording more than once, variation in surname spellings, and mixed recording of conventional versus Spanish surname practices.

With regards to accounting for and transcribing race, whatever race the head of household was, the enumerators identified his children with the same race. For example, if the head of household was Filipino or Chinese and even though they were married to a

CHamoru female, their children were categorized with their father’s race. This is contrary to ancient

CHamoru society where the children “belong to their mother and her avuncuclan” (

Cunningham 1987, p. 71). In addition, during the 1819 French expedition of the Uranie to the Mariana Islands, junior surgeon Jean-Paul Gaimard noted the

CHamoru practice for families of a deceased wife would reclaim the children and all household possessions on the basis, “that he only obtained those things because of his marriage and because while they could be sure that the children were hers, they could not have the same certitude that they were his.” (

Milsom 2019, Loc 2883–2894)

After transcribing the 1930 Census, our observations were similar to what we found in the 1920 Census. However, in reconciling the transcription against the official population data (18,509), there were actually 18,512 names recorded in the census (

NARA 1930). The difference of three were: two additional names were found in District 11 (Municipality of Sumay) and one in District 13 (Naval Reservations and Ships).

We once again also identified the oldest female and male, top ten most common female and male first names, top ten common surnames, and variation in surname spellings. We found at least what appears to be 68 duplicate recordings of the some individuals and families; based on the names and ages. In addition, some individuals, particularly those who may have served as Cooks or Servants at other households may have been inadvertently recorded twice. It also seems that the reason some family members may have been recorded twice and at separate locations is because they may have maintained one permanent residence and the other residence may have been for farming.

For the 1920 and 1930 census, Maria and Jose were the most popular names among the female and male population, respectively. In addition, the surname Cruz was also at the top among the most common surname. Indeed, this observation reiterates the essence of capturing nicknames and CHamoru family clans, to narrow down and identify certain people when constructing or reconstructing family trees from source documents or oral histories.

7. Presentations and Live Broadcasts

Through all this data mining and research effort I have been blessed to provide some presentations on some of the work produced.

Festival of Chamorro Arts, 2016, San Diego, California (presentation and genealogy workshop)

Festival of the Pacific Arts, 2016, Guam (seminar and genealogy workshop)

Pacific Islands Bilingual-Bicultural Association (PIBBA), 2016 (presentation)

University of Minnesota, 2017, (presentation and genealogy workshop)

I was able to provide some live feeds using the FB application on my cellular phone for portions of these presentations. Unfortunately, I experienced inconsistent cell phone data speeds that eventually interrupted and disconnected the live feed. Even when I tried to leverage public Wi-Fi at a couple of those venues, those connections were not reliable either.

Recently, I have also conducted some trial live FB presentations from my home office with live broadcasting software. These sessions were piloted only among friends and not the public just yet. This option requires more work and effort on studying and evaluating the various broadcasting software that are available, but my goals are to engage more participation and collaboration through this effort. The two types of broadcasting software being tested are Open Broadcasting Software (OBS) (

Bailey n.d.). OBS is a free and open source. The second is ManyCam, which requires a paid license (

Visicom Media Inc. n.d.). So far, the software that appears to be the easiest to setup and resulted with the least amount of glitches during a live broadcast session is OBS. During the piloting of these live feeds, I was able to demonstrate the capabilities and features of the Project’s website.

8. Conclusions

After querying 2010 data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s website, it revealed 64% of the

CHamoru population were residing in the U.S. and 36% back in the Mariana Islands (

American FactFinder n.d.). The diaspora is expected to increase when the 2020 U.S. Census is completed. These percentages are increasing at an alarmingly rate and makes it more important to ensure outreach and global accessibility of these resources produced from this Project. The products from the Chamorro Genealogy Projects will continue to add to the availability of

CHamoru genealogy resources locally and abroad. In addition, as a key data-mining resource of

CHamoru genealogy information, we hope it will entice more scholars to collaborate, review and interpret the data collected, which has the potential to provide another aspect of and add to the knowledgebase of

CHamoru history from a genealogical lens. See

Figure 2.