1. Introduction

Whakapapa is the Māori word for genealogy, and can be interpreted literally as ‘the process of layering one thing upon another’ (

Ngata [1944] 2011, p. 6). For many, everything has a whakapapa. Accordingly, there is a genealogy for every word, thought, object, mineral, place and person (

Roberts 2015). Some see whakapapa as ‘the skeletal structure of Māori knowledge’, while others emphasise it as an organising framework for Māori history (

Tau 2001, p. 73;

Keenan 2000). The importance of whakapapa in the Māori world is paramount because it is considered crucial to assertions of Māori identity and tribal membership. Ngai Tahu leader, Tipene O’Regan, once remarked that whakapapa ‘carries the ultimate expression’ of who he is, and that without it he would be simply an ‘ethnic statistic’ (

O’Regan 1987, p. 142). In my tribe, Ngāti Porou, whakapapa has been described as the ‘heart and core of all Māori institutions from Creation to what is now iwi’ (

Mahuika 1998, p. 219). Since the arrival of European colonisers, whakapapa has been defined, used, and researched in various ways. There is a broad array of writing and research on whakapapa, much of which is scattered in studies on tribal histories, Māori myths, folklore, songs, Land Court Minute Books, personal memoirs, Māori newspapers, research on carving, education, politics, biographies and ethnographies. This essay surveys the multiple ways in which whakapapa has been addressed since the nineteenth century. While there is an array of commentary on whakapapa, there is no single study that traces the way it has been engaged with over the past century. This paper then, is ambitious in its desire to canvass that history and, with a limited word count, cannot include everything on the subject. It nonetheless strives to highlight some key approaches that have impacted the way we think about, and research, whakapapa in Aotearoa New Zealand.

2. Whakapapa as an Explanatory Framework

Whakapapa has been at the heart of Māori history and knowledge long before, and well after, European invasion. Genealogical connections, before and after British unsettlement, played a significant role in the way tribe’s related to each other and identified themselves. Whakapapa is hierarchical and has been central to the way Māori organised social and political units, from large groupings or iwi (tribes) to hapū (subtribe) and whānau (families).

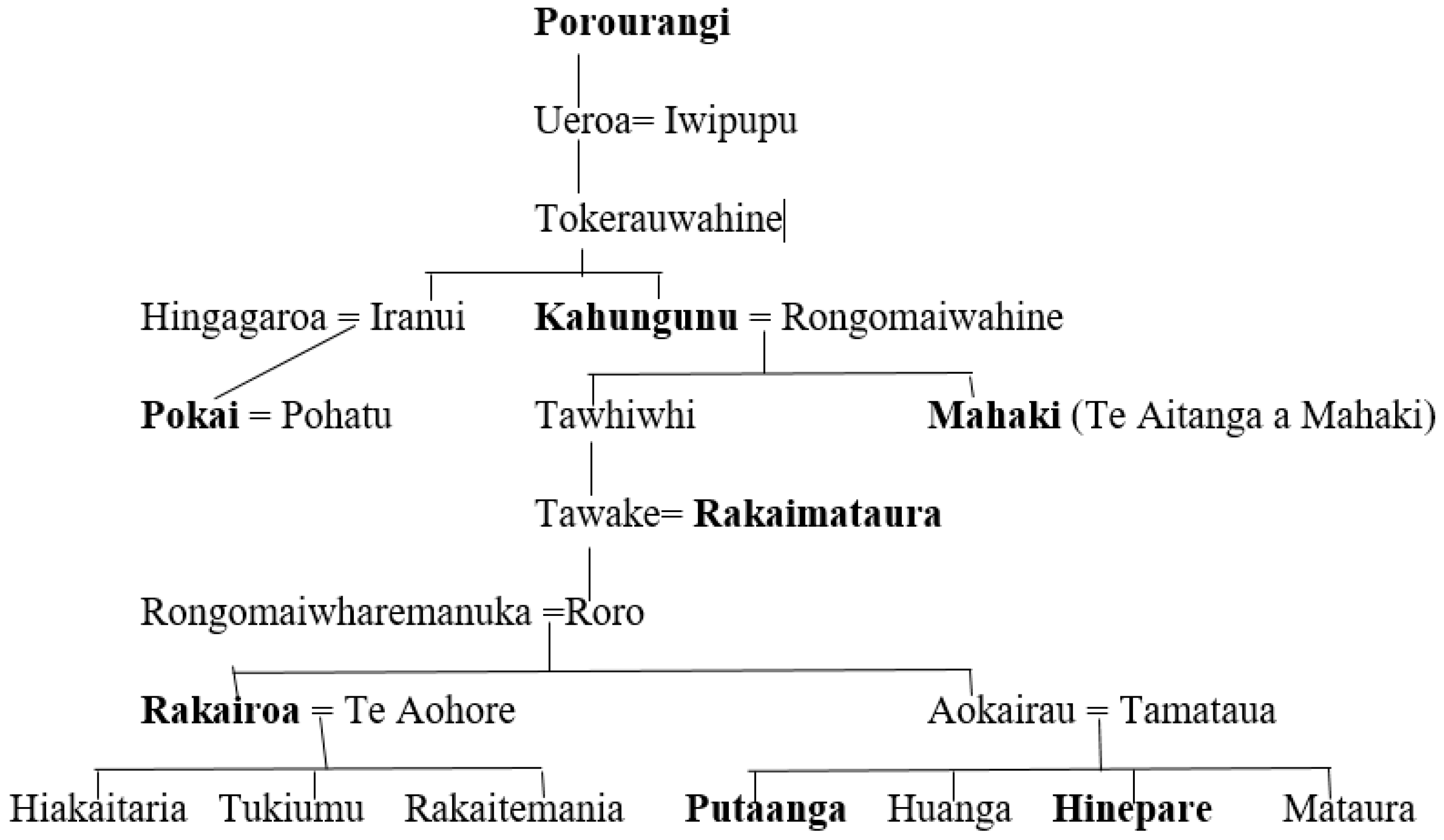

1 Iwi and hapū were generally named after key ancestors, like Ngāti Porou who take their name from the eponymous ancestor Porourangi. In the following whakapapa table, Porourangi’s connection to other tribes and sub-tribal ancestors is indicated in bold: See

Figure 1.

Kahungunu, while descended from Porourangi identify as their own separate and autonomous iwi, as do the descendants of Mahaki. In contrast, the whānau of Pokai, Rakaimataura and Rakairoa are often considered hapū found in smaller family groupings that are part of the larger Ngāti Porou iwi collective. Kahungunu and Mahaki occupy different territory, but have strong whakapapa connections to Ngāti Porou. These genealogies connect Māori back to the Pacific and to Ariki (the literal descendants of the Gods) and Atua (Gods) that in Māori culture and history are believed to exercise dominion and authority over the natural and spiritual worlds. Porourangi, then, is a descendent of Paikea (the whale rider), Hine Mahuika (the Goddess of fire) and the well-known Polynesian ‘trickster’ and ‘demi-god’, Māui (

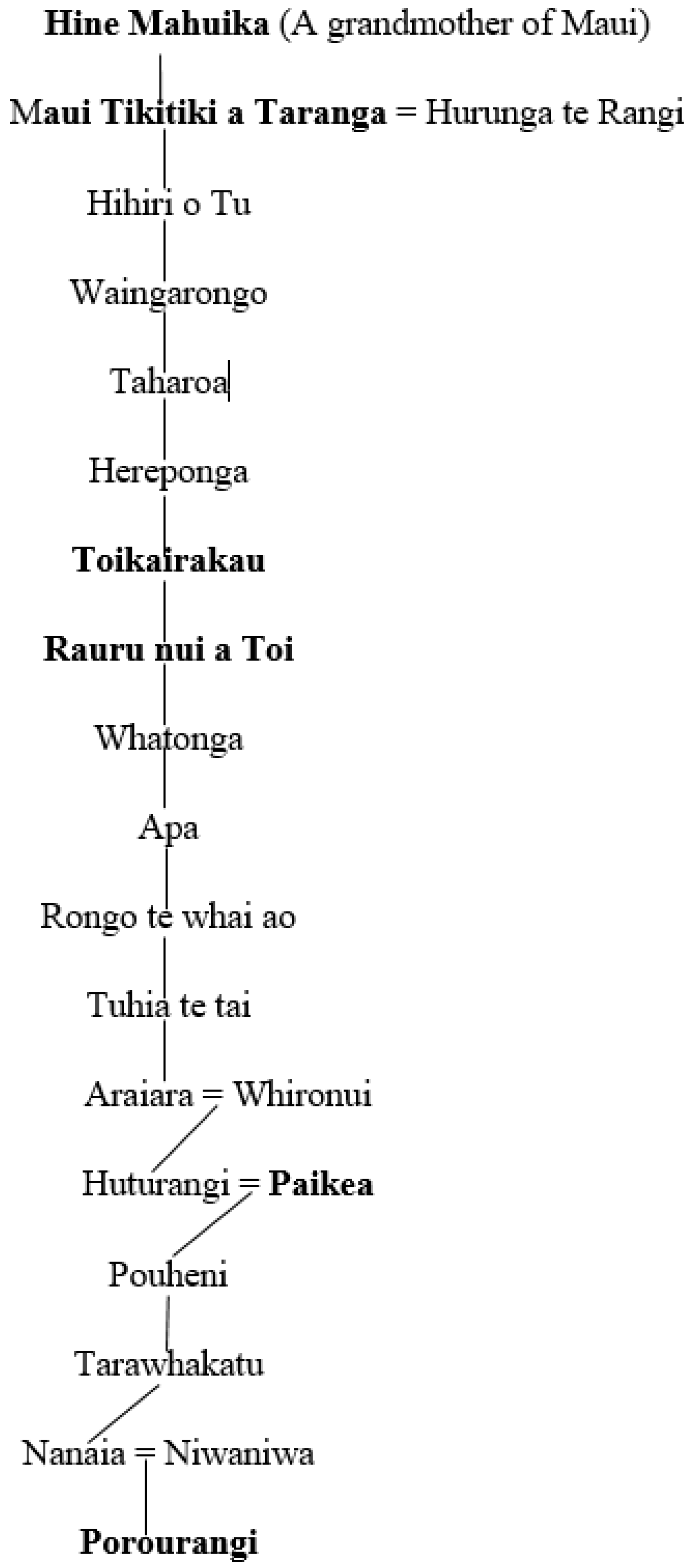

Luomala 1949): See

Figure 2.

In this genealogy we learn that Paikea and Porourangi are descendants of Toi, Rauru and Whatonga, all significant figures in the Pacific that Apirana Ngata once described as the most aristocratic stock in Polynesia. These whakapapa emphasise ocean and island lineages, and are reference points to the many ‘Hawaiki’ or ‘origin points’ from where ancestral Māori navigators set sail (

Smith 1910;

Kōhere 1920). Genealogies, like these, have framed the history of waka (canoe) migrations, and are illustrations of how whakapapa assert human genealogies that coalesce with the supernatural and spiritual planes. The Māori natural and spiritual worlds were expounded in genealogies that gave meaning to landmarks, fauna, flora and phenomena, the roles of men and women, and divine descent. These whakapapa chronicled evolutions from the beginning of time, providing explanatory frameworks for the world and everything in it. Māori genealogy was primarily transmitted orally up until the advent of writing and print in the nineteenth century, and today remains more of an oral tradition and performance than it is a written practice. In

The Ancient History of the Māori published in 1890, John White recorded the recitations of the nineteenth century Ngāti Kahungunu elder Mohi Tawake, who recounted the ‘descendants of Ranginui (the sky father) and Papatūānuku (the earth mother)’:

Rangi took Papa to wife and begat Tāne te wai ora (Tāne male of the living waters) who had Po nui (the great night) and Ao roa (the long day)’.

Genealogies like these described what some have termed ‘divisions’ or ‘states’ of Māori whakapapa and history. John White’s reference to Rangi and Papa above, fit into what he called the three ‘divisions’, which are ‘Popoa-rengarenga (Genealogy of the Gods)’, ‘Takiura (a genealogy of the ancestors who followed after or were immediately descended from the Gods)’, and ‘Tua-tangata (genealogy of man)’ (

White 1890, pp. iii, iv). Almost a century later, Ranginui Walker suggested a similar interpretation of Māori genealogy in what he argued were ‘three states of existence’ that recounted the origins of life from ‘te kore’ (the void), to ‘te po’ (the dark), and ‘te ao mārama’ (the world of light) (

Walker 1992, p. 11). While epochs of time were genealogically ordered, so too were histories regarding the development of memory, thought and consciousness. One of the more famous examples is this recitation regarding the evolution of thought:

| Nā te kune te pupuke | From the conception the increase |

| Nā te pupuke te hihiri | From the increase the thought |

| Nā te hihiri te mahara | From the thought the remembrance |

| Nā te mahara te hinengaro | From the remembrance the consciousness |

| Nā te hinengaro te manako | From the consciousness the desire. |

| Ka hua te wānanga. | Knowledge became fruitful |

Whether referring to abstract concepts, deities, physical and material objects, practices, people, or places, Māori prior to and after the arrival of Europeans, maintained genealogies that traced all things to living beings in complex interwoven connections. Whakapapa first and foremost explained the world and served as a framework upon which Māori could hang all of the concepts and narratives pivotal to their identity, culture, politics, language and religions.

As nineteenth century British colonisers tried to comprehend the Māori world, they remarked on how Māori shaped ‘their political and social divisions as descent groups’ and through specific lineage to eponymous ancestors and waka groupings (

Ballara 1998, p. 63). The intricately connected world of whakapapa that the invaders encountered made it difficult for them to purchase land from just any Māori, and complicated simplistic ideas around Māori leadership, territory, and intertribal politics and hierarchies. Whakapapa prior to the arrival of Europeans was a lived experience taught orally through schools of learning or wānanga that were reserved for individuals selected because of their social rank and perceived skills and abilities to memorise and retain information. Most whakapapa experts prior to the advent of print and arrival of colonisers held important positions in their tribes and were considered more priests, spiritual leaders or tohunga (experts) than historians or merely genealogists.

2 Approaches to whakapapa, however, changed with the arrival of Europeans, whose incredulity of oral histories, belief in their own superiority, and desire to own indigenous culture not only undermined traditional experts but shifted whakapapa to print where it became subject to Pākehā scrutiny, legal interpretation, or displaced by colonisers as unreliable superstitions and myth.

3. Whakapapa and Pākehā Researchers

Early Pākehā researchers, missionaries and ethnographers especially, were avid collectors of Māori genealogies. John White (noted above) filled much of his work with genealogy tables. He, along with other nineteenth and early twentieth century researchers like Edward Shortland, Richard Taylor, Sir George Grey, Elsdon Best, Edward Treager and Stephenson Percy Smith sought out whakapapa, finding experts from within Māori communities to both inform their work and provide interpretations. Others, like Walter Edward Gudgeon, drew on Māori Land Court records to furnish their histories. By the 1840s, increasing literacy coupled with Pākehā curiosity about Māori customs and peoples, led to an intensifying of the transition of whakapapa and tribal histories to print (

Anderson et al. 2014, p. 74). Whakapapa, which had been long viewed as sacred, treasured, and specific to tribes was being gathered and redeployed to accommodate Pākehā desires to understand and manage their new environment (

Gibbons 2002, p. 7). Within the new-comers work, ancestors who were previously accepted as real and living in Māori genealogy were reimagined in fables and legends that colonisers called Polynesian mythologies and fairytales (

Reed 1974, p. 1). Māui became a mythical being, sometimes a ‘Hercules of the Pacific’, while Hine-ahu-one was transformed into a ‘Dawn-maid’, and the male issue of Tāne-nui-a-rangi the ‘Maori Adam’ (

Clark 1896;

Condliffe 1930). During this period, researchers—predominantly non-Māori—developed approaches to whakapapa that went on to influence generations of scholars in Māori history. W. E. Gudgeon, a nineteenth century Native Land Court Judge, as Athol Anderson writes ‘advocated arranging tribal histories and genealogies into a single history of Maori’ (

Anderson et al. 2014, p. 52). Simple singular narratives were not normative to Māori oral history, and in writing tended to strip genealogies down in order to massage them into coherent accounts that often erased or misinterpreted the nuances that inform and acknowledge competing tribal identities. This was only one of the problems with Gudgeon’s commitment to recorded Land Court whakapapa rather than local expertise. Land Court testimonies were not necessarily reliable sources of genealogical data. Angela Ballara has pointed out the ‘problems associated with using Land Court evidence, not the least of which is legibility’ (

Ballara 1998, p. 44). Genealogical testimony in the Minute Books were often difficult to read, incomplete, and composed in an adversarial context that pitted Māori against each other. Gudgeon has since been criticised for his inability to understand the context of the whakapapa he was referencing (

Mahuika 2007, Rec.3: 13.46–18.12;

Gudgeon 1972). While Māori embraced literacy, print, and coloniser technologies, whakapapa and Māori oral history during this time were displaced and often rejected by Pākehā as ‘a mixture of unsifted fact and fable’, ‘superstition’ and the ‘puerile imaginings’ of a ‘primitive race’ (

Sinclair 1980, p. 18;

Grey [1855] 1956, p. x;

Taylor 1855, p. vi). This process has been referred to as ‘cultural colonization’ in which ‘Maori themselves and their cultures were textualized by Pākehā from the nineteenth century onward, so that the colonists could “know” the people they were displacing’ (

Gibbons 2002, p. 13).

The most significant approach to whakapapa brought by non-Māori researchers in the nineteenth century was a genealogical method or system of counting and dating generations popularised in the work of the Polynesian Society (

Sorrenson 1992, p. 21). This approach was promoted by a range of researchers and genealogical specialists, including J. B. W. Robertson who drew his examples from Tainui whakapapa and Edward Shortland who compared dates to whakapapa of South Island Māori (

Robertson 1956,

1958;

Shortland 1856). For some, in averaging generations back to waka migration, this method could help align Māori history with standard Western conceptions of time. The singular narrative that arose from this approach was promoted by Stephenson Percy Smith via his theory of a Great Fleet which he calculated arrived in 1350 AD (

Smith 1898,

1910;

King 2003, p. 45). Using this method, estimations regarding Māori canoe arrivals varied, with some averaging 20 generations, and others like Elsdon Best, who focused on Tuhoe whakapapa, suggesting 16.5 generations back to Toroa from the Mataatua canoe. But the genealogical method, despite its popularity and widespread use and appeal was fraught with problems (

Sharp 1958,

1959).

4. Whakapapa and Māori Writing

While Pākehā researchers focused on counting generations back to possible waka arrivals, Māori who had embraced literacy and writing began to commit their oral records to print (

McRae 2002). It was common, as Bruce Biggs, writes ‘for Māori families to keep manuscript books’ and recorded genealogies. Many of these books, he pointed out, were accidentally destroyed or ignored and avoided because they were believed to be tapu (sacred or restricted) and possibly malevolent (

Biggs and Mead 1964, p. 3). By the twentieth century whakapapa books and collections of songs were kept by a large number of families (

Mahuika 2007, Rec.1: 18.48–19.02). These books were sometimes lost and buried with relatives, while others were taken, stolen or hidden (

Mere 2008, Rec.2: 2.29–4.10). In my tribe, whakapapa books were remembered by some as finely crafted texts with ‘beautiful writing’ (

Donaldson 2008, Rec.1: 35.35–36.48). Today, some of these books have survived, almost a century old and are kept by descendants whose ancestors were keepers of family genealogy (

Taiapa 2007, Rec.1: 28.53–30.30). Those who speak about these texts assert that the books themselves are not meant to replace the mode of oral delivery, but are there to support tribal orators who prepare to deliver that knowledge following the conventions of traditional speech making. Whakapapa as a methodology in this way, then, is supposed to be stored ‘in the Māori mind’ and imparted on the marae (tribal meeting ground) contextualised in our cultural settings (

Lardelli 2007, Rec.1: 14.47–15.41). Whakapapa is part of our cultural practice, supported by songs, proverbs, karakia (incantations), and best presented in the Māori language. Nevertheless, books served as an adjunct to support the archiving and dissemination of genealogies from one generation to the next. For many, genealogy remained something learnt by ear, taught in the mnemonic rhythms and repetition of chants and songs. Mervyn Mclean writes that manuscripts and books were used to aid learning, but ‘by and large, people picked them up simply by hearing them performed in context’ (

McLean 1989, p. 13). Different tribes by the twentieth century, then, established and held special schools of learning in order to educate new generations and practice the memorising and delivery of whakapapa.

3 For Māori, whakapapa books although adherent to writing and literacy still carried underlying oral and traditional conventions in the way data was recorded. ‘Tarere’ or single descent lines, for instance, showing intermarriage to kin, was, according to Apirana Ngata, the usual method of tracing adopted in most whakapapa books (

Ngata [1944] 2011, p. 6).

5. Whakapapa and Māori Terminology

The genealogical method advanced by Smith and others may not have been well known by most Māori at the beginning of the twentieth century, but Apirana Ngata, an ardent supporter of the Polynesian Society, promoted it in his ‘Rauru nui a Toi Lectures’ in the 1940s (

Ngata [1944] 2011). The Polynesian Society, Ngata emphasised, considered whakapapa ‘indispensable in reconstructing Maori history’ and by the twentieth century had advocated specific conventions in regard to their use that Ngata felt should be taken up by Māori themselves. According to Ngata, the two primary conventions were:

- (a)

That the length of a generation may be taken as twenty five years. So that if an average of a number of lines of descent from a common ancestor the length is say eighteen generations then that ancestor lived about four and a half centuries ago.

- (b)

By using this method the mean of generations from the crews of Te Arawa, Mataatua, Takitimu, Tainui and other canoes of what is called the fleet, the date of that migration is given as the year 1350 A.D. (

Ngata [1944] 2011, pp. 4–5).

Ngata was not the only Māori scholar in support of this approach to whakapapa or to Percy Smith’s ‘Great Fleet’ theory. In 1958, Pei te Hurinui Jones, wrote of his conviction that Tainui ‘lines of descent from the Fleet’ were also authentic. He observed that whakapapa appeared ‘to be giving some Europeans trouble’, and thus it might be helpful if native experts supported confused Pākehā unaccustomed to difficult Māori names (

Jones 1958, p. 162). For Ngata, it was important to find ways to use the genealogical method to assist in the retention and teaching of whakapapa. He stressed that while genealogies should be written down, they are best ‘memorised’ through ‘the ear’ and should only be ‘recited on appropriate occasions’ (

Ngata [1944] 2011, pp. 5, 8). Ngata was specific about the way whakapapa should be presented both orally and in writing. When writing, students were to use a ‘foolscap size’ notebook and ensure that each genealogy table was numbered in the margins by multiples of five so that corresponding notes would synchronise with the correct line of the whakapapa (

Ngata [1944] 2011, p. 5). One of the great gifts in Ngata’s work was his attention and detail to the terminology of whakapapa, which revealed the depth of Māori conventions in regard to the presentation of genealogical knowledge. Some of this essential terminology included:

| Whakamoe | the intermarriages in the lines of descent. |

| Taotahi | to recall a descent line without listing a spouse. |

| Tararere | to trace a single descent line without showing |

| | intermarriage to their kin. |

| Tāhū | the main lines or the principal ancestors of the tribe. |

| Whakapiri | ones connection to another line. |

| Kauwhau taki | the term used for tracing whakapapa, |

| | meaning to ‘recite, declare’ |

| Raraka Kôrero | tells of the traditions notes differences between junior and senior lines |

Whether writing or reciting whakapapa, Ngata argued that it was important to understand that Māori had their own conventions and terms to describe various types of genealogical tables. To refer to the ‘Tāhū’ of a genealogy, as Ngata argued, meant to set out the main lines or stock ancestors of a tribe (

Ngata [1944] 2011, p. 6). ‘Whakapiri’, he revealed, seeks a common connecting ancestor with the audience or person you are addressing. Once that link is found, Ngata writes that ‘you have to consider whether he or you are of the same elder branch, so that you may call him tuakana [older relative] or taina [a younger relative]’ (

Ngata [1944] 2011, p. 7). This terminology, then, reflected specific cultural understanding crucial to the way whakapapa should be used and understood in Māori contexts. Ngata’s writing in the first half of the twentieth century offers an invaluable vocabulary specifically relevant to Māori genealogy (

Ngata 2019, p. 19). It reveals how crucial it is to be proficient in te reo Māori (the Māori language) because whakapapa is not just a list of Māori names or words, but is an act best comprehended in the language itself. Each of the words as he explained have much deeper meanings in the Māori world:

| Tatai | to arrange or set in order. |

| Hikohiko | to skips names on the vertical line down |

| | and sometimes interpolate names on the horizontal plane. |

| Ure tane and | |

| whakaparu wahine | Tracing through male or female lines |

Apirana Mahuika, a student of Ngata’s, explained that tatai-hikohiko is the ‘practice of indicating a line of descent by naming a few ancestors on that line without giving a complete line’ (

Mahuika 1974, p. 7). In following Ngata’s teaching, Mahuika argued that Ngāti Porou people must remain in control of the cultural adaptions that are a part of our genealogical inheritance, and that this includes the language of whakapapa and an understanding of the tikanga (protocols) related to genealogical transmission (

Mahuika 1999, p. 68). Ngata’s approach sought to adapt and use the genealogical dating method to support the production, and validation, of whakapapa. His insistence on correct terminology accentuated the fact that Māori themselves maintained conventions and language about how, and in what ways, whakapapa should be compiled and presented. Whakapapa, as Ngata observed, should be both a written and oral practice, but mastery in it required a knowledge of the Māori language, an appropriate repertoire of songs and proverbs together with a firm grasp of the terms used to recite it. Moreover, Ngata understood whakapapa as a body of knowledge, or framework, inextricably connected to traditional songs and incantations (

Ngata and Jones [2004] 2005). Ngata had hoped that this body of work would inform a course in Māori studies, however he died before he was able to complete his collections. He understood at a much deeper level the way in which Māori people of his era valued, kept, and responded to, their own specific genealogical lineages. Whakapapa, then, was a central factor in the establishment of the 28th Māori Battalion that served alongside other New Zealand forces during the Second World War. Adopting an already common whakapapa based on existing canoe genealogies, Ngata organised the Battalion into these well-known waka collectives that grouped various tribes together (

Mahuika 2010a, p. 158;

Soutar 2008, pp. 45–49). For Māori, whakapapa continued to be a key factor in composing history, whether written or oral, and the majority of written tribal histories produced in the twentieth century were organised within waka genealogies. These included Pei Jones and Bruce Biggs’ (

Jones and Biggs 1995)

Ngā Iwi o Tainui,

Rongowhakaata Halbert’s (

1999)

Horouta,

Tiaki Mitchell’s (

1997) history of

Takitimu,

T. G. Hammond’s (

1924)

Aotea and

Don Stafford’s (

1986)

Te Arawa. This emphasis changed as attention turned to specific tribal land claims and settlements toward the end of the twentieth century.

6. Rethinking Genealogical Methods

Whakapapa as a specific topic of study and methodology in the mid-twentieth century was largely addressed in articles published through the Journal of The Polynesian Society. J. B. W. Robertson, Pei Te Hurinui Jones, D. R. Simmonds, and other authors such as Leslie G. Kelly all contributed to ongoing discussions regarding the value of whakapapa and what had up until that point become a predominantly accepted theory of Māori migration and the ‘Great Fleet.’

The genealogical method advanced by Stephenson Percy Smith and embraced by Apirana Ngata and others was severely critiqued in the second half of the twentieth century. Smith’s theory was criticised by both Andrew Sharp and later by D. R. Simmons who both doubted the genealogical consistency across tribal whakapapa (

Anderson et al. 2014, p. 63). In

The Great New Zealand Myth, Simmons reviewed and tested Smith’s assertion and found that the evidence did not align with different tribal generational data or with Kupe’s supposed arrival date. Simmons argued that Smith had manipulated the evidence to accommodate his story, and that the twenty five year per generation calculation produced different dates for various tribes (

Simmons 1976, p. 307). This genealogical method based in the averaging of generations was, however, not the only approach popular in Aotearoa and the Pacific. Anthropologists influenced by the work of W. H. R. Rivers also practiced a genealogical methodology based in interviews with native peoples that sought to explain their insights around kinship, inheritance, and succession (

Rivers 1900,

1910). Ethnographers like Raymond Firth promoted this genealogical method as part of his studies in Tikopia (

Firth 1959). While Ngata and Pei Te Hurinui were influenced by Percy Smith’s approach to genealogy, other Māori later in the twentieth century responded to the work of Firth and those interested in kinship and primogeniture. An increasing number of Māori theses produced from the 1970s onward included and commented on whakapapa. In his study of female leadership, Apirana Mahuika, for instance, used tribal whakapapa to challenge the idea that Māori leadership is primarily determined through the male line (

Mahuika 1974). Like Ngata he accentuated the importance of understanding the indigenous terminology around primogeniture and structures of Māori kinship in order to better interpret and understand whakapapa. His work, like many others from the 1970s onward emphasised a desire by Māori to take back ownership of the way whakapapa might be used and thought of as a methodology. It is not surprising that this coincided with the Land Marches in 1975, the Bastion Point occupation in 1977 and Springbok Tour protests in 1981. Māori efforts to bring greater political awareness to the Treaty of Waitangi and Māori rights impacted also on a desire to take ownership of our own history and mātauranga (knowledge).

With the advent of the Waitangi Tribunal, and the energy of a new generation of activists, approaches to whakapapa from the 1980s onward tended to focus less on anthropological and ethnographical questions about kinship, and more on land claims and historic grievances. Re-energised by new generations committed to language revitalisation, decolonisation and Māori autonomy, whakapapa research turned to new readings of the Land Court Minute Books and interviews by Māori with Māori pakeke (elders). The place of whakapapa as crucial to Māori identity and history influenced new commentators interested in genealogy as a method and as the framework for Māori epistemologies. By the 1990s Māori were describing whakapapa approaches in various ways. Charles Te Ahukaramu Royal, for instance, described whakapapa as a research methodology or tool apt in the analysis of natural ‘phenomena’, origins, connections and relationships, and even predicting the future’ (

Royal 1998, pp. 6–8). Tipene O’Regan stressed the living and connected nature of whakapapa between ancestors and Māori in the present, stating that ‘my past is not a dead thing to be examined on the postmortem bench of science without my consent and without an effective recognition that I and my whakapapa are alive and kicking’ (

O’Regan 1987, p. 142). O’Regan’s message emphasised the importance of ownership and an ethics around genealogical research. His assertion followed more than a decade of Māori commentators demanding that Pākehā and non-Māori reconsider their status as ‘experts’ in Māori culture, and step aside to allow Māori to take back ownership of their own knowledge. On this issue Keri Kaa remarked that:

We have kept quiet for too long about how we truly feel about what is written about us by people from another culture. For years we have provided academic ethnic fodder for research and researchers. Perhaps it is time we set things straight by getting down to the enormous task of writing about ourselves.

This was not simply a result of post 1970s’ protests. Māori had felt this way for some time. In a letter to his friend Apirana Ngata, Te Rangihiroa (Peter Buck) had, for instance, many decades earlier (in 1931) suggested that the time for Elsdon Best and others is over, and that we as Māori must take responsibility for researching our world for ourselves (Buck cited in

Sorrenson 1987, p. 115).

At the beginning of the twenty first century, Māori scholarship had moved toward a decolonising politics, in which the reclaiming of our knowledge also meant repossessing methods and definitions of whakapapa. As Moana Jackson has insisted: ‘we have to reclaim the right to define ourselves, who we are, and what our rights are. We have to challenge definitions that are not our own especially those which confine us to a subordinate place’ (

Jackson 1998, p. 73). Reassertions of the meaning of whakapapa, then, tended to highlight a need to remove it from non-Māori frameworks. ‘Whakapapa korero’, according to Takirirangi Smith for instance, are better understood as ‘discourses held by tangata whenua’ and provide important narratives of Māori identity (

Smith 2000, p. 53). Smith argued that ‘whakapapa korero belongs to a different spatial and temporal reality than the lineal temporal sequence of European ideas of history and myth’ and thus ‘a major problematic is raised with the imposition of a Western historical framework in the interpretation of whakapapa korero’ (

Smith 2000, p. 54). Like Smith, Ngai Tahu historian, Rawiri Te Maire Tau also highlighted the specifically indigenous importance of whakapapa as ‘the skeletal structure to mātauranga Māori’ or what he calls ‘Māori epistemology’ (

Tau 2001, p. 73). For both, Māori genealogy did not fit or belong within Western frameworks of history, and thus to understand and better use whakapapa it is necessary to situate it within its Māori epistemological roots. Whakapapa as a body of knowledge and approach has in the past decade been emphasised as a crucial aspect of Māori identity. Of whakapapa, Joe Te Rito has written that it grounds him ‘firmly in place and time’, and connects us to the past in ways that confirm our identity as Māori through a deep sense of ‘being’ (

Te Rito 2007, p. 9). Whakapapa as a framework for understanding identity has informed studies on ‘Urban Māori’ identities (

Smith 2012) and research regarding family identity and ‘experiences’ (

Walker 2013). Family research and genealogy remains a popular practice for Māori who through colonial assimilation have been disconnected from a knowledge of their own history and whakapapa. The very few Māori guides and manuals dedicated to tribal and family research all stress whakapapa as the key methodological approach (

Joyce et al. 2008;

Roberts 2006;

Royal 1992;

Te Awekotuku 1991). Other studies like Ngarino Ellis’

A Whakapapa of Tradition (

Ellis 2016) surveyed a hundred years of tribal carving, revealing a sophisticated intergenerational negotiation of internal and external cultural knowledge. In each case, whakapapa served as a framework to explore intergenerational cultural transmissions, and how these have shaped various Māori identities, whether personal, collective, urban, cultural or explicitly relative to the art of whakairo (carving).

Beyond these explicit analyses of identity, others like James Graham have highlighted the importance of whakapapa in the way our institutions work. He argues, for instance, that ‘whakapapa facilitates the institution’s behaviour by upholding the use of a distinctive tribal kawa [customs] that guides certain tikanga Māori [Māori protocols]’ (

Graham 2009, p. 6). This approach, similar to Tipene O’Regans views about the ownership of Māori genealogy and history, emphasises the place of whakapapa within Māori communities and therefore a crucial aspect of research ethics. The ethics of whakapapa has its own broad array of commentary. Māori have reminded museums and curators, for example, that the true custodianship of Māori artefacts belong first and foremost to those peoples who have specific genealogical relationships with those taonga (treasures). Whakapapa, then, is part of the requirement for one to exercise guardianship or ‘kaitiakitanga’ (

Mahuika 2010b). More recently, whakapapa has become the subject of research in bioscience and genetics with some exploring the potential of ‘whakapapa as a foundation for genetic research’ (

Hudson et al. 2007;

Evans 2012). The ethical questions posed here note that access to whakapapa is ‘usually restricted’ and that the transference of ‘whakapapa and the genetic material associated with it’ across generations is considered by many Māori to be tapu (

Hudson et al. 2007, p. 46).

In this brief history of whakapapa in academic and private practice, there are some consistent themes about the very nature of Māori genealogical knowledge. It is, and always has been, grounded in cultural protocols and contexts that are paramount to the way Māori identify and relate to each other and the world around them. Whakapapa as an approach, whether it be relevant to genetics, history, education, or elsewhere, is inextricably connected to underlying protocols and tribal ethics. Whakapapa has its own tribal specific, and collective Māori, politics that seek out connections and inclusivity and are necessarily exclusive when it comes to exercising and asserting ownership and authority. Māori whakapapa are also part of genealogical discussions in the Pacific and in the wider indigenous global community. Whakapapa resonates with the ways in which our relatives in the Pacific understand genealogy and the fact that indigenous genealogies ‘have rarely been the subjects of historians’ and yet from our perspectives as native peoples absolutely constitute viable histories (

Salesa 2014, p. 41). Like us, other indigenous peoples confirm that genealogical research in their communities ‘requires special knowledge and skills, as well as access’ and are rarely the province of all (

Salesa 2014, p. 42). Their perceptions of genealogies corroborate the view that in the telling of stories ‘genealogies create the conditions for debate, particularly when it comes to making claims on status, rank, authority, and mana (spiritual power, prestige), especially in matters of succession’ (

Tengan et al. 2010, p. 139). Māori approaches to genealogy and its many iterations in research and practice has long sought out an embracing of knowledge beyond our homelands. Whakapapa is consistently being tested and applied to new situations. Vanessa Paki and Sally Peters, for instance, have recently referred to whakapapa as a tool for conducting research as a cultural concept to mapping transition journeys from early child learning institutions to schools (

Paki and Peters 2015, p. 49). In her work, Marama Salsano, has examined whakapapa ‘as literary analysis’, arguing that it ‘encompasses a series of layers that can reveal huge areas of knowledge’ but requires ‘the learner to live whakapapa as a conscious activity’ (

Salsano 2016, pp. 36, 39). Living whakapapa to truly understand it, as opposed to just using it when convenient, underlines the long lasting truth of the way whakapapa has been dealt with and defined since the arrival of European colonisers. From the beginning, whakapapa was the whole world, an explanatory framework for life and our place in it. In all the various ways it has been addressed by non-Māori and our own people across time, this foundational aspect of whakapapa has persevered: that whakapapa is everything, and everything has a whakapapa.