Robertson at the City: Portrait of a Cemetery Superintendent

Abstract

:1. Introduction

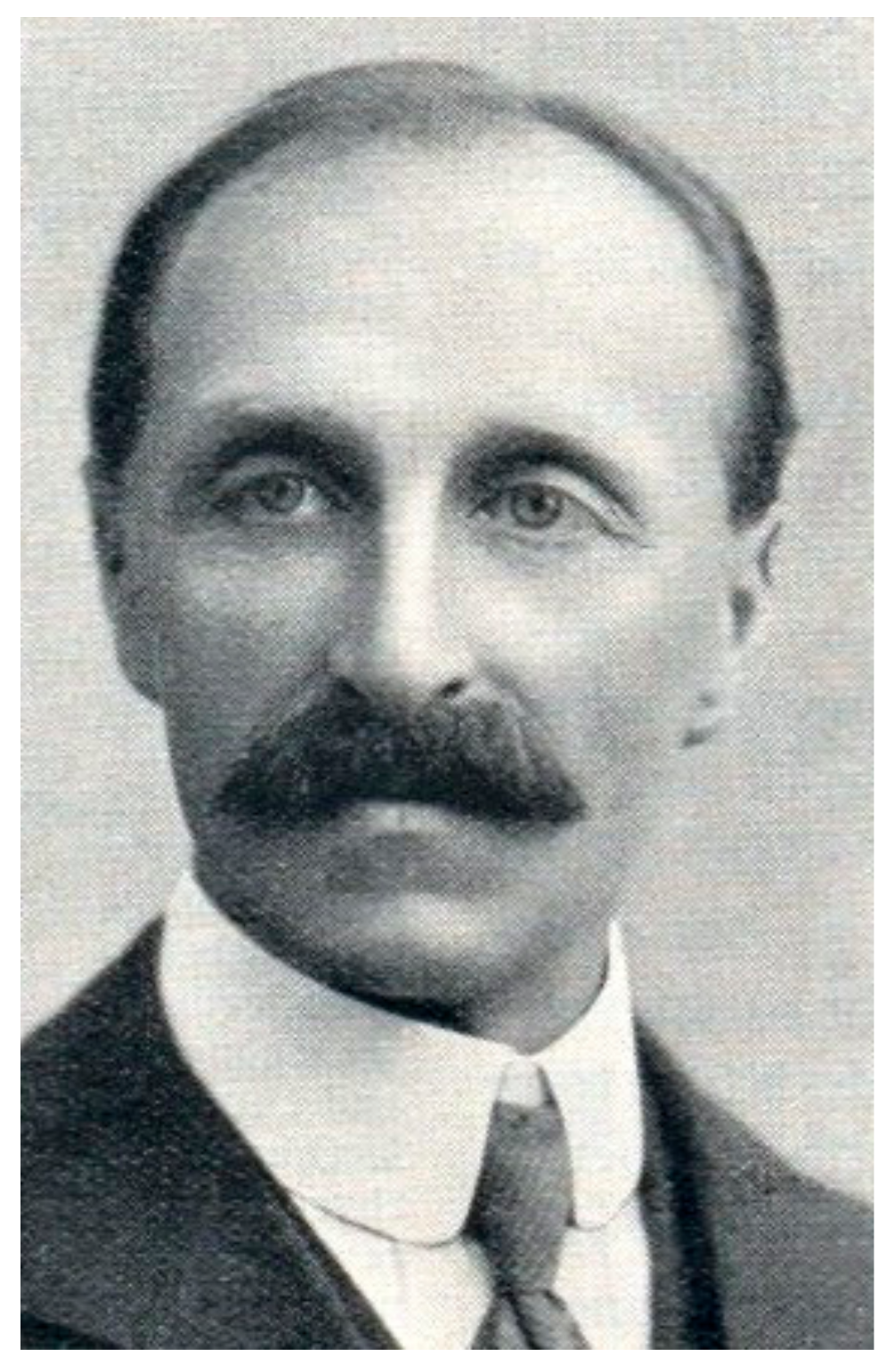

2. John Duncan Robertson

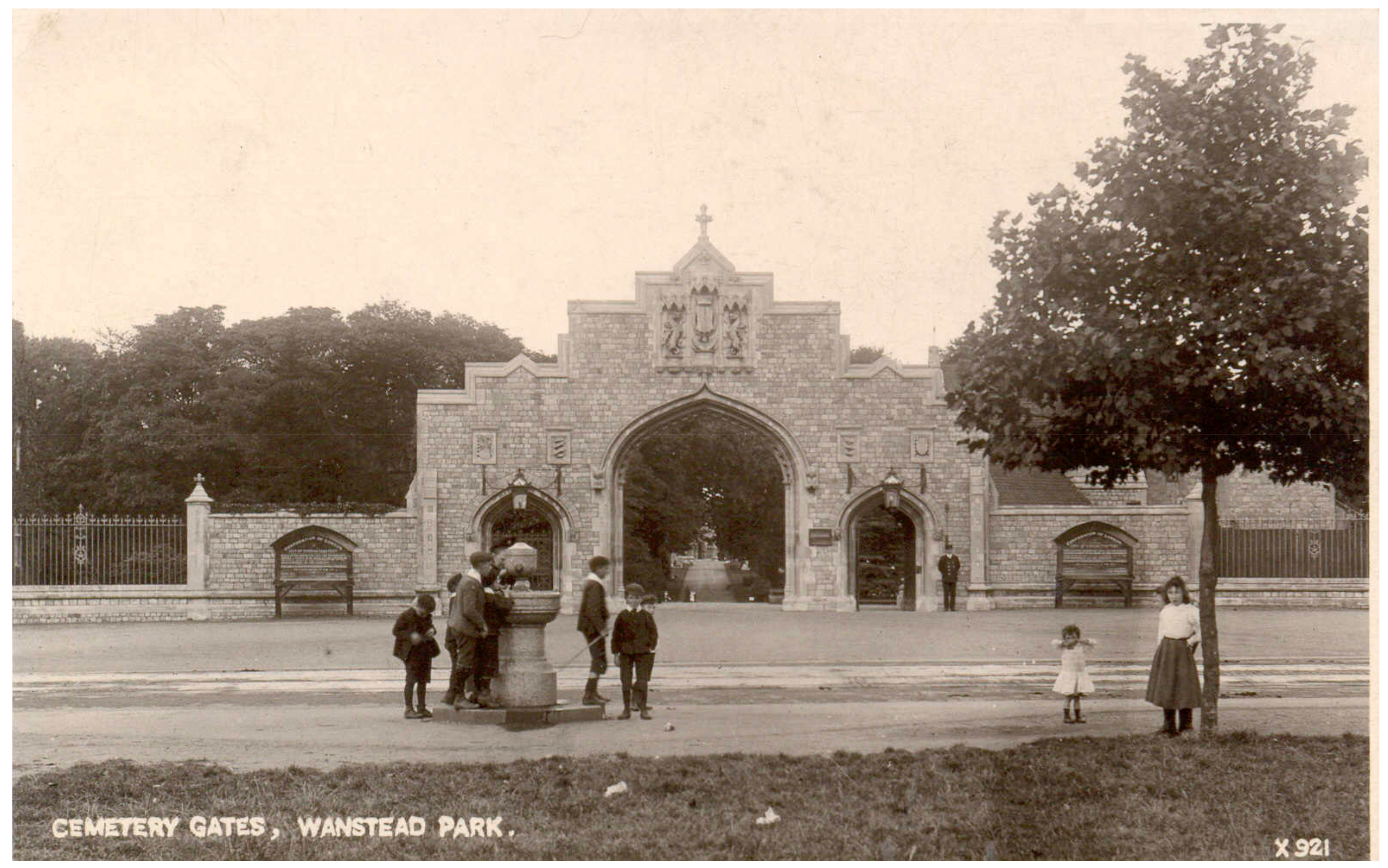

3. Robertson at the City of London Cemetery

4. Robertson and the National Association of Cemetery Superintendents

- To further the interests of cemetery superintendents and promote the efficiency of cemeteries in the United Kingdom

- To promote the knowledge of work appertaining to the management of cemeteries

- To provide facilities and foster social intercourse amongst members.12

- Gas Meter Inspector £250

- Chief Inspector of Weights and Measures £400

- Inspector of Sewers £250

- Chief of Cleansing and Watering £40014

5. Robertson and Cremation

‘… let me say that no modern cemetery is fully equipped unless it has a crematorium … The modern cemetery, like the great departmental store which is fully equipped in all departments, should be able to offer to the public all the known legal forms of disposal, which of course includes cremation.’

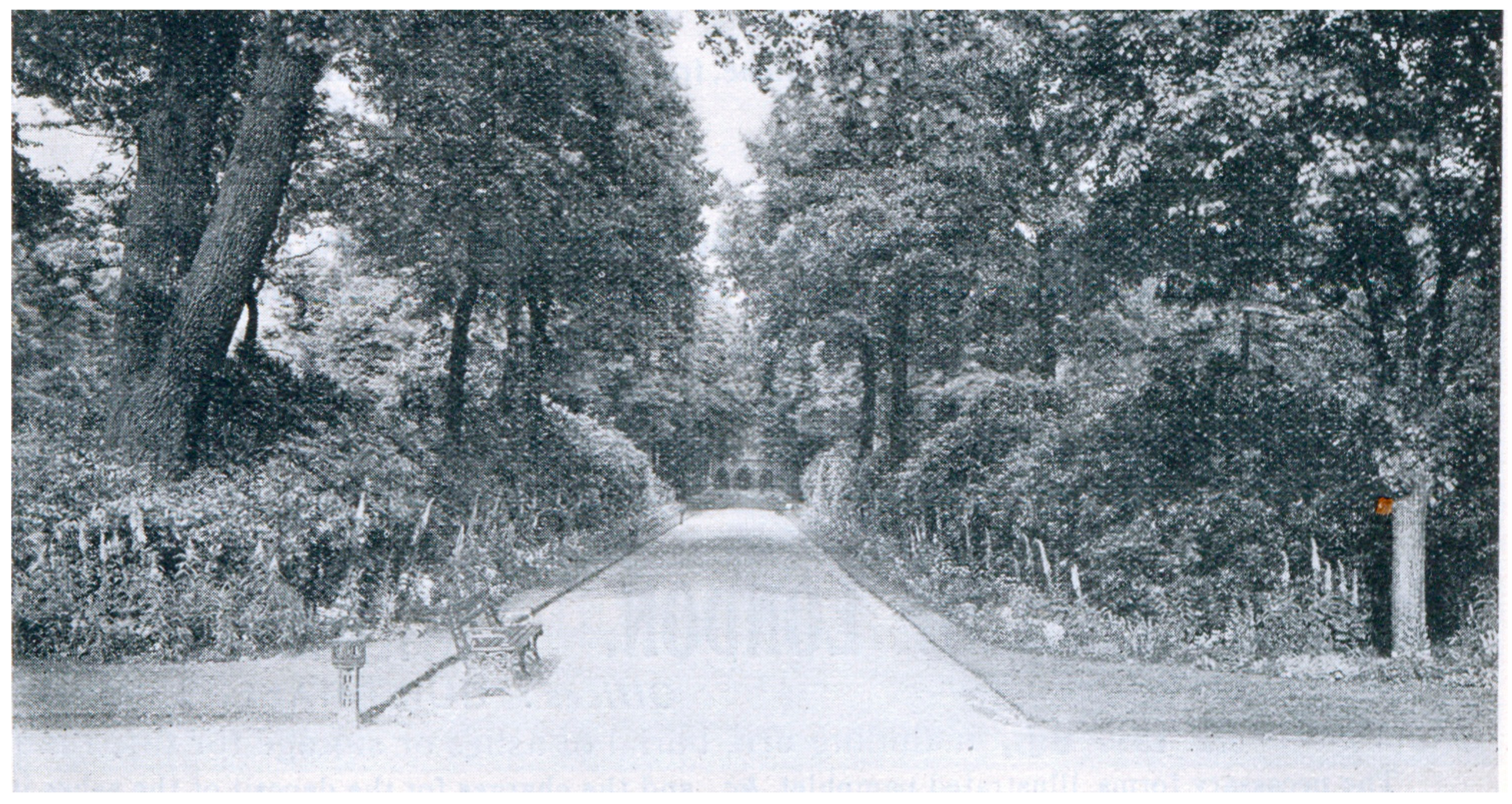

6. Robertson as a Writer on Cemetery Management

Again, he noted the differences:‘…although park-like schemes should be introduced, sight should not be lost of the fact that many features suitable to park planning may not always be in accord with cemetery requirements, but a combination of both would bring into being the most suitable for the cemetery; always bearing in mind the area of land to be treated, and its topographical features.’

The hallmark of an ideal cemetery was good planting and in one article he commented that, ‘The seasonal floral displays in many cases compare favorably with many of our public parks and gardens.’32 This leads into the second point, that planting should be coherent. Showy or what he termed ‘gay displays’ were to be avoided and should be replaced with‘In the preparation of the plans, the designer should visualize a park for, in the words of an authority of this subject, cemeteries in this country are becoming more attractive from an aesthetic point of view, while many of our parks are gradually given over more and more to sports of various forms which generally curtails space for floral display.’

‘…tasteful attractions…to lure the visitor to a continual round of fresh discoveries that would in no way exhaust interest or appear improperly placed, and would reveal a combination of efforts in harmony with our best landscape traditions.’

‘The grounds to be laid out on the park cemetery principle (you know how much one sees of the chess-board cemetery in this country). The artistic relations between memorials and landscape; drainage and sanitation; models of modern and up-to-date chapels, crematoria, columbarium, and urn courts and model office administration.’

7. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. ‘The Modern or Ideal Cemetery’ by JD Robertson

Appendix B. Other Articles by John Robertson

Archival Material

References

- Hey, David, ed. 2010. The Oxford Companion to Family and Local History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, David. 2006. The Cemetery in a Garden. 150 Years of the City of London Cemetery and Crematorium. London: City of London Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Loudon, John Claudius. 1843. On the Laying Out, Planting and Managing of Cemeteries; and on the Improvement of Churchyards. London: Longman, Brown Green and Longmans. [Google Scholar]

- Mawson, Prentice E. 1935. Garden Cemeteries. Landscape and Garden 11: 125–27. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, Brian. 2005. Where did the ashes go? The development of cremation and disposal of ashes 1885–1950. Part 2—From Grave to Gardens: Scattering and Gardens of Remembrance. ICCM Journal 73: 28–42. [Google Scholar]

- Rugg, Julie. 2006. Lawn Cemeteries: The emergence of a new landscape of death. Urban History 33: 213–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, F. 1932. British War Cemeteries. TUJ August: 247. [Google Scholar]

- Webster, Angus D. 1920. London Trees. London: Swarthmore Press. [Google Scholar]

- Weed, Howard E. 1912. Modern Park Cemeteries. Chicago: HJ Haight. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Robertson, J.D. (1938) Horticulture in the Cemetery TUJ, October, p. 378. |

| 2 | ‘Presentation’ (1936) JNACCS, No 4 November, vol. 2, p. 19. |

| 3 | See ‘London News Items’ (1920) TUJ, November, p. 344 |

| 4 | ‘Death of Mrs JD Robertson’ (1933) TUJ, February, p. 60. Robertson, J.D. (1938) ‘From the Cape to the Zambezi’ TUFDJ, August, pp. 299–300 & Robertson, J.D. (1940) ‘A Tour of New Zealand’ TUFDJ, January, pp. 9–10 & Robertson, J.D. (1940) ‘A Tour of the Far East and Back’ TUFDJ, December, pp. 327–28. |

| 5 | ‘Mr JD Robertson’ (1942) TUFDJ, May, p. 102. |

| 6 | London Metropolitan Archive Col/CC/PBC/04, p. 25. |

| 7 | ‘The City of London Cemetery and Crematorium’ (1915) TUJ, August, pp. 223–26. |

| 8 | Ibid. |

| 9 | This was the case for 1914. See Col/CC/PBC/01/02/07 23, February 1915. |

| 10 | ‘Association of Cemetery Superintendents’ (1913) TUJ, November, p. 303. |

| 11 | ‘Association of Cemetery Superintendents’ (1914) TUJ, February, p. 51, ‘The United Kingdom Association of Cemetery Superintendents’ (1914) TUJ, May, p. 146 and TUJ, August, p. 213. |

| 12 | ‘Interview with Mr JD Robertson’ (1915) TUJ, June, pp. 165–66. |

| 13 | ‘The United Kingdom Association of Cemetery Superintendents. Annual Congress’ (1916) TUJ, September, pp. 255–56. See also ‘The National Association of Cemetery Superintendents’ (1918) TUJ, July, p. 190. |

| 14 | Col/PBC/01/02/016. 25 November 1913. |

| 15 | ‘United Kingdom Association of Cemetery Superintendents’ (1916) TUJ, September, p. 254. |

| 16 | ‘National Association of Cemetery Superintendents: Sixth Annual Congress’ (1921) TUJ, August, p. 283. |

| 17 | ‘National Association of Cemetery Superintendents: Council Meeting 21 January 1928’ (1928) TUJ, February, p. 68. |

| 18 | Robertson, J.D. (1918) ‘Cremation—A War-Time Consideration’ TUJ, May, p. 132. |

| 19 | ‘No One to Bury the Dead. Cremation for all’ (1917) TUJ, January, pp. 25–26 and Robertson, J.D. (1918) ‘Cremation—A War-Time Consideration’ TUJ, May, p. 132. |

| 20 | Robertson, J.D. (1917) ‘The Relationship between Undertakers and Cemetery Superintendents’ TUJ, July, pp. 189–90. He also contributed ‘Undertakers and the Law of Burials’ (1926) BUA Monthly, March, pp. 186–87. |

| 21 | Robertson, J.D. (1920) ‘Cremation: its Advantages over Earth Burial’ TUJ, May, pp. 145–46; Robertson, J.D. (1931) ‘Cremation from the Cemetery Superintendent’s Point of View’ TUJ, August, p. 268. |

| 22 | Robertson, J.D. (1924) ‘Cremation and Economics—Individual, Municipal and National’ TUJ, September, pp. 319–20. |

| 23 | ‘Fifth Annual Conference of Cremation Authorities’ (1926) TUJ, November, p. 362. |

| 24 | See Superintendent’s Day Book 28 April 1931, p. 91. |

| 25 | Robertson, J.D. (1931) ‘Cremation from the Cemetery Superintendent’s Point of View’ TUJ, August, pp. 266–68. Robertson, J.D. (1931) ‘Cremation from the Cemetery Superintendent’s Point of View’ BUA Monthly, October, pp. 93–94. See also ‘National Association of Cemetery Superintendents Annual Congress (1923) TUJ, July, p. 256. |

| 26 | Col/CC/PBC/01/01/032. |

| 27 | Robertson, J.D. (1931) ‘Crematoria: Bright and Cheerful’ TUJ, November, p. 372. |

| 28 | See ‘National Association of Cemetery and Crematoria (sic) Superintendents’ (1933) TUJ, May, p. 161. |

| 29 | At the NACS conference in 1929 he gave ‘The Modern Cemetery—Selection and Planning.’ ‘Fourteenth Annual Conference’ (1929) TUJ, June, p. 193. |

| 30 | Robertson, J.D. (1931) ‘Development of Cemeteries and Crematoria: Cemetery Plans’ TUJ, April, p. 131. |

| 31 | Ibid. |

| 32 | Ibid. |

| 33 | Robertson, J.D. (1919) ‘The Modern or Ideal Cemetery: Planting’ TUJ, March, p. 85. |

| 34 | Robertson, J.D. (1917) ‘The Modern or Ideal Cemetery: Preparing the Plans, Continued’ TUJ, April, pp. 98–99. |

| 35 | Robertson, J.D. (1919) ‘The Modern or Ideal Cemetery: Staff’ TUJ, November, p. 340. |

| 36 | Robertson, J.D. (1917) ‘The Modern or Ideal Cemetery: Preparing the Plans, Continued’ TUJ, April, pp. 98–99, and Robertson, J.D. (1919) ‘The Modern or Ideal Cemetery: Monuments’ TUJ, June, pp. 175–77. |

| 37 | ‘Cemeteries as Parks’ (1914) TUJ, March, p. 73. |

| 38 | ‘An Exhibition that may be’ (1915) TUJ, October, p. 265. |

| 39 | ‘The Official Organ of the NACS’ (1923) TUJ, February, p. 59. This was not carried out due to lack of space. |

| 40 | Col/CC/PBC/01/02/037, 24 January 1933. See also Superintendent’s Day Book, 24 January 1933, p. 101. |

| 41 | Wimbledon Borough Council: Minutes of the Council, 10 May 1933, para. 1088. |

| 42 | Minutes of Proceedings taken before the Select Committee of the House of Lords on the Wimbledon Corporation Bill, 24 March 1933, pp. 82–92. |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Parsons, B. Robertson at the City: Portrait of a Cemetery Superintendent. Genealogy 2018, 2, 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy2030031

Parsons B. Robertson at the City: Portrait of a Cemetery Superintendent. Genealogy. 2018; 2(3):31. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy2030031

Chicago/Turabian StyleParsons, Brian. 2018. "Robertson at the City: Portrait of a Cemetery Superintendent" Genealogy 2, no. 3: 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy2030031

APA StyleParsons, B. (2018). Robertson at the City: Portrait of a Cemetery Superintendent. Genealogy, 2(3), 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy2030031