Abstract

This paper outlines Darwin’s theory of descent with modification in order to show that it is genealogical in a narrow sense, and that from this point of view, it can be understood as one of the basic models and sources—also indirectly via Nietzsche—of Foucault’s conception of genealogy. Therefore, this essay aims to overcome the impression of a strong opposition to Darwin that arises from Foucault’s critique of the “evolutionistic” research of “origin”—understood as Ursprung and not as Entstehung. By highlighting Darwin’s interpretation of the principles of extinction, divergence of character, and of the many complex contingencies and slight modifications in the becoming of species, this essay shows how his genealogical framework demonstrates an affinity, even if only partially, with Foucault’s genealogy.

Keywords:

Darwin; Foucault; genealogy; natural genealogies; teleology; evolution; extinction; origin; Entstehung; rudimentary organs “Our classifications will come to be, as far as they can be so made, genealogies; and will then truly give what may be called the plan of creation. The rules for classifying will no doubt become simpler when we have a definite object in view. We possess no pedigrees or armorial bearings; and we have to discover and trace the many diverging lines of descent in our natural genealogies, by characters of any kind which have long been inherited. Rudimentary organs will speak infallibly with respect to the nature of long-lost structures. […]. When we can feel assured that all the individuals of the same species, and all the closely allied species of most genera, have within a not very remote period descended from one parent, and have migrated from some one birth-place; and when we better know the many means of migration, then, by the light which geology now throws, and will continue to throw, on former changes of climate and of the level of the land, we shall surely be enabled to trace in an admirable manner the former migrations of the inhabitants of the whole world”.(Darwin 1859–1876, p. 426, emphasis mine)

This is one of the final passages from On the Origin of Species, in which Darwin explains how his new theory will transform the entire traditional system of classification of the forms of life into genealogies. This transformation represents one of the strongest impacts of the new theory of “descent with modification”—usually interpreted as “Darwin’s evolutionistic theory”—on the traditional fixist, essentialist, and teleological framework, in which the natural species were understood as unchangeable forms, determined from a predetermined essence, and thought of in a teleological way. Darwin posits the new genealogical classification as “the only possible arrangement” of “all the organic beings, extinct and recent, which have ever lived” (Darwin 1859–1876, p. 395, emphasis mine)1; which means that natural genealogies are not a theoretical integration of, nor an improvement on, the classical Natural System. Instead, they represent a new way of (re)arranging this whole system. In a very radical way, Darwin’s genealogy overcomes the old framework based on the assumptions of a fixed aim for every organ and part (directly or indirectly) that was established from the beginning of the species and which preserves the static, harmonious, and hierarchical natural system (this is the traditional œconomia naturae).

It is for this reason that, on a theoretical and methodological level, Darwin highlights the importance of the presence of rudimentary or useless organs: parts of the body—like the “mammæ of male mammals”—that no longer have any life functions, and that therefore cannot be explained in a teleological way (Darwin 1859–1876, p. 381)2. The young Darwin wrote: in these cases, there is “no final cause,” (Darwin 1987a), which means that we cannot think of single organs as things that are determined by a fixed and unchangeable connection between form and function, and that they have always been perfectly adapted to the organism’s environment. On the contrary, only a genealogical approach can offer a coherent explanation of these organs that do not have any aim, any vital function, any utility; they must be interpreted as “the record of a former state of things”. These organs can therefore help us to discover the ancient genealogies: “they have been retained solely through the power of inheritance, —we can understand, on the genealogical view of classification, how it is that systematists, in placing organisms in their proper places in the natural system, have often found rudimentary parts as useful as, or even sometimes more useful than, parts of high physiological importance. Rudimentary organs may be compared with the letters in a word, still retained in the spelling, but become useless in the pronunciation […]” (Darwin 1859–1876, p. 402, emphasis mine). By using these “letters”, among many other elements, we can proceed in the discovery of the many diverging lines of descent of every living species, in order to obtain a picture of the ancient forms of life. However, it’s certainly a very complicated task. Darwin explains: “we possess only the last volume of the geological record, and that in a very broken condition, we have no right to expect, except in rare cases, to fill up the wide intervals in the natural system, and thus to unite distinct families or orders” (Darwin 1859–1876, p. 305). We can therefore understand why Darwin writes that the community of descent is the hidden bond that has to be found (Darwin 1859–1876, p. 369).

This research of the community of descent is then based on a genealogical arrangement of the species in a narrow sense: the basilar theoretical assumption of this approach is that “all the individuals of the same species, and all the closely allied species of most genera, have […] descended from one parent”. If Darwin’s concept of natural genealogies is also linked or shaped using the traditional theoretical model of family genealogies, it has to do not only with the individual level offspring of the same species (as in family genealogies), but also with a genealogical arrangement of the different levels and degrees of modification of the natural system (varieties, species, genera, and so on). He explains: “I believe that the arrangement of the groups within each class, in due subordination and relation to each other, must be strictly genealogical in order to be natural; but that the amount of difference in the several branches or groups, though allied in the same degree in blood to their common progenitor, may differ greatly, being due to the different degrees of modification which they have undergone; and this is expressed by the forms being ranked under different genera, families, sections, or orders.” (Darwin 1859–1876, p. 369, emphasis mine). It is considering this specific and crucial use of the concept of “genealogy” to (re)arrange the whole Natural System that Darwin should be considered one of the fathers of the modern way to theorize the history of life forms, and more generally, the history of living nature, including humankind, in a genealogical way. Darwin’s concern for explaining the history of all organic beings, extinct and recent, leads directly to natural genealogies understood as lines of descent, even if the “old” genera and forms are usually extinct.

In what follows I will maintain—even if only by way of an introductory argument—that Darwin’s genealogies show several affinities with, and could also be thought of as an indirect source of, the genealogical approach developed by Michel Foucault, especially in his famous essay Nietzsche, Genealogy, History (Foucault 1971). This is actually a topic that is very poorly investigated. An important exception is Philipp Sarasin’s voluminous “experimental book” Darwin und Foucault, in which there is an extensive analysis of the relations between the two doctrines, and an analysis of the reception of Darwinism in the twentieth century, with an emphasis on the concept of natural selection, and the question of the “perfection”, “progress”, and “continuity/discontinuity” of the forms of life, along with the crucial concept of “struggle for life” (from Malthus onwards) (Sarasin 2009, pp. 222–63)3; (Atterton 1994). In the present paper, I will instead focus on the anti-teleological and also anti-essentialist character of Darwin’s theoretical framework of natural genealogies, showing, in so doing, the crucial role given to the micro and accidental individual variations, the significance of extinction, and some other elements. I will also outline some of the basic elements of Foucault’s genealogy, understood as an abstract method of research, highlighting its anti-teleological and anti-essentialist character.

Proceeding by way of this abstract comparison, I will, first of all, overcome the misleading impression that Foucault’s critique of the “evolutionistic” and teleological search for the origin should be understood as a (justified) critique of Darwin’s theory of descent with modification. I also explain that Foucault’s critique of “evolutionism” is one of the reasons why the affinities, and also the possible influence of Darwin’s theory on Foucault’s idea of genealogy, remains so poorly investigated. To overcome this impression, I will then show that the anti-teleological and anti-essentialist qualities of Foucault’s genealogical methodology, which aim to promote the singularity, relative autonomy, and contingency of cultural-historical events, are actually similar to the basic qualities of Darwin’s theoretical framework that aimed to explain the historical forms and changings of natural genealogies. In other words, I believe that Foucault’s critique of “evolutionism” must be understood first of all as advanced against a peculiar doctrine of evolutionism that does not coincide with Darwin’s theory, but that should be defined as pseudo-Darwinian. Even though I will not present a detailed analysis of Foucault’s interpretation of the history of life sciences and biology, I will outline some of the principle (above all negative) meanings of the concepts of “evolution” and “evolutionism” in his works of the Sixties and early Seventies (Foucault 1966, 1969; Foucault 1970, 1972). If these concepts have in Foucault a general negative meaning, it’s at the same time important to remember that in Nietzsche, Genealogy, History, he never quotes the name of “Darwin”, and—as we will see—in another essay devoted to Cuvier, he has explicitly connected Darwin with the concept of “genealogy”. In any case, my analysis will be developed on the level of an abstract comparison between the two genealogical models, and it is from this point of view that the teleological (and essentialistic) character that Foucault ascribes to the “evolutionistic” research for origin cannot be referred to Darwin in a justified way.

Pursuing this first basic task, I will also examine the possible influence of Darwin’s theoretical framework on Foucault’s genealogical methodology. In this regard, we can assume that the passage made by Foucault from the strictly “archaeological” to the “genealogical” methodology reflects the influence of Nietzsche (Davidson 1986; Flynn 2005). It’s also well known how much Darwin’s theory influenced Nietzsche’s genealogical approach, and then, at least indirectly, Foucault (Mahon 1992; Richardson 2004; Saar 2007; Johnson 2010; Koopman 2013; Sarasin 2009). If then Foucault has stressed the difference, or even the opposition, between Nietzsche’s concepts of Ursprung, understood as the “origin” researched within the evolutionistic framework, and Entstehung, understood as the “beginning” analysed within the genealogical framework, we have, however, to remember that the standard German translation of Darwin’s Origin of the Species was Über Entstehung der Arten. Hence, at the linguistic level, the critique advanced against the “evolutionistic” concept of origin can be misleading if we do not consider that Darwin’s standard German translation of origin is indeed Entstehung, as well as Ursprung: the two terms are constantly used in the German translation as synonyms (Darwin 1876). In other words, the distinction that Foucault tries to establish (via Nietzsche) (Nietzsche 1892) between the two concepts is inconsistent if we are referring to the German translation of Darwin’s Origin of the Species. Additionally, from a philological point of view, the objections that Foucault advances against the “evolutionistic” model of the search for origin (Ursprung) as opposed to the genealogical model of beginnings (Entstehung) cannot be consistently referred to Darwin. More generally, I think that we can easily support the argument that Foucault’s genealogical method could find, at least via Nietzsche, one of its numberless beginnings—because there are also, at this historical-methodological level, numberless beginnings, or numberless Entstehungen—in Darwin’s genealogical approach. However, I will only pursue this second task in an indirect way: not trying to show the (actually very complicated) relations between Darwin, Nietzsche, and Foucault’s historical-genealogical approaches (Johnson 2010), but outlining some of the basic affinities between the two genealogical theoretical frameworks.

In pursuing these two tasks, I will first try to show that in Darwin’s thematization of the genealogical tree of life, the process of descent with modification works not only with the well-known principle of natural selection, but also with the two other principles of extinction and divergence of character. From this point of view, Darwin’s theory is actually a radical alternative to the teleological and essentialist approach of the traditional framework, as for example, the role of rudimentary and useless organs clearly shows. In short, I will show that Darwin is doubtless one of the fathers of the modern way to think about historical natural processes in a strictly genealogical way (part I). In a second step, I will focus attention on some crucial points of Foucault’s idea of genealogy, remarking on its anti-teleological and anti-essentialist character, and the centrality given to the singularity and contingency of cultural-historical events. In this discussion, I explore some structural convergences between Foucault’s and Darwin’s theoretical framework, including several specific mechanisms and processes concerning the modification of species. In short, in this part, I will analyse both the negative side of the two genealogical methods, as well some of their positive qualities (part II).

1. Darwin’s Genealogical Tree of Life

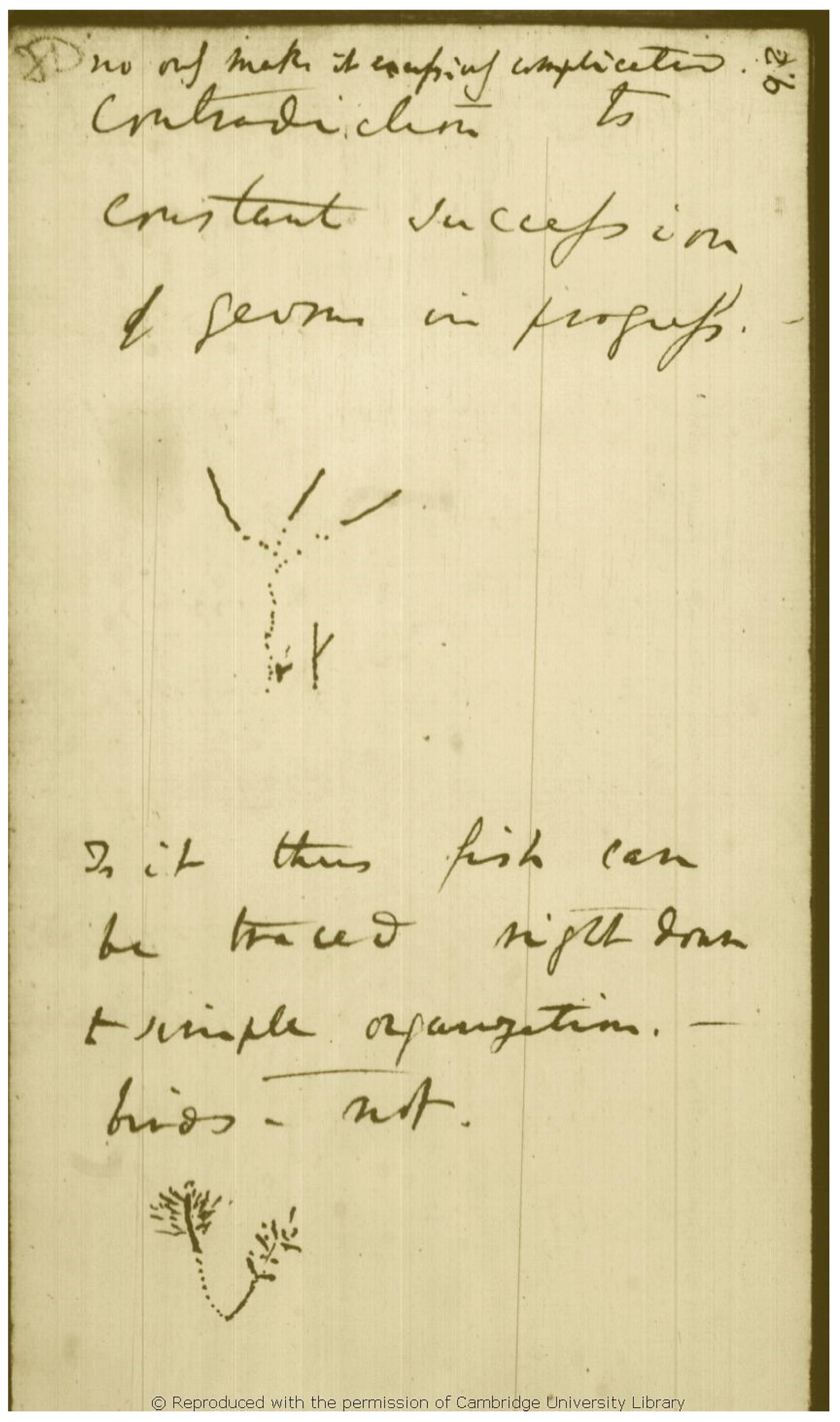

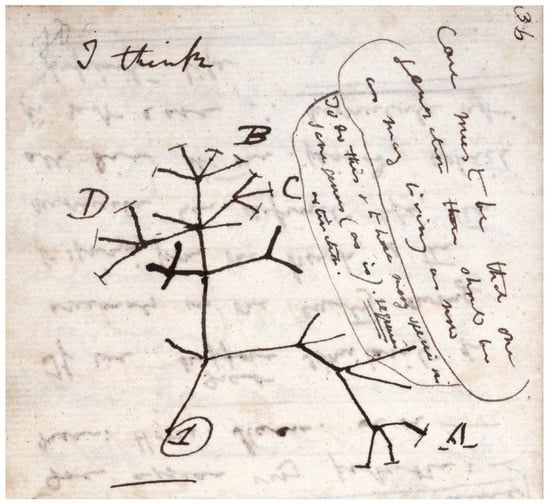

Darwin’s revolutionary re-organization of the classical image of a stable and unchangeable ladder or scale of beings, began with the elaboration of a picture of a tree of life, or rather of a coral of life with irregular and dead branches. This is an image that opposes the static and linear scala naturae with the historically diverging lines of natural genealogies (Barsanti 1992; Archibald 2014). This new image clearly emerges in one of Darwin’s private notebooks (called B, and written during the years 1837–1838) that he began to use just after his voyage on the Beagle (1831–36). In Notebook B, Darwin sketched two pictures of trees (see the reproduction) and wrote: “Organized beings represent a tree irregularly branched some branches far more branched—Hence Genera […]. There is nothing stranger in death of species than individuals […] those which have changed most owing to the accident of positions must in each state of existence have shortest life. Hence shortness of life of Mammalia”; then Darwin concludes: “We need not think that fish & penguins really pass into each other.—The tree of life should perhaps be called the coral of life, base of branches dead; so that passages cannot be seen” (Darwin 1960, pp. 21–26, emphasis mine)4; (Archibald 2014, p. 80 ff). (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Darwin, Notebook B—Transmutation of species (1837–1838), p. 26.

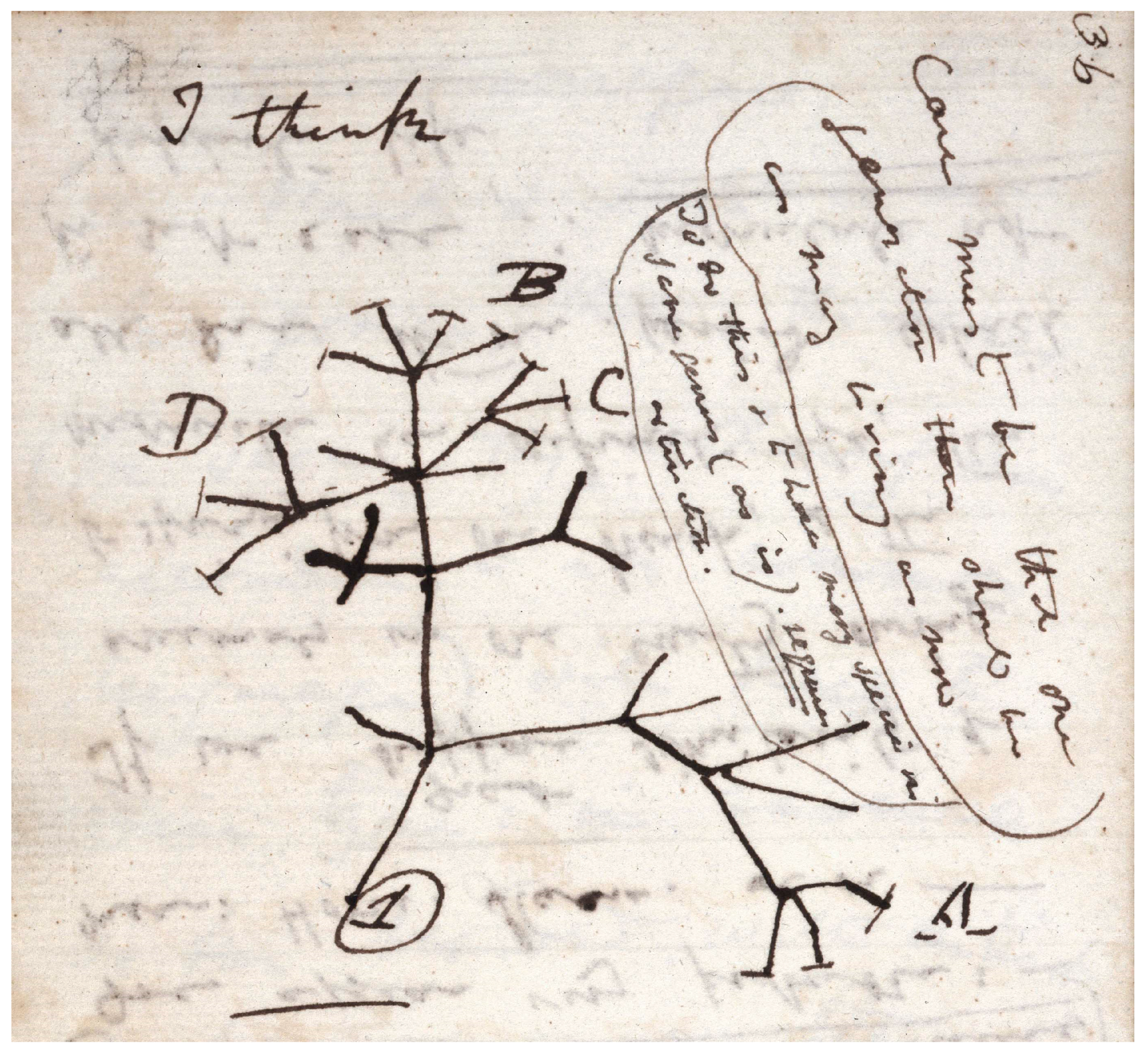

As we can see from the sketches in this notebook (Darwin 1960, p. 26)5, Darwin started to think of his theory of descent with modification from a strictly genealogical point of view. Darwin attributes great significance to the process of extinction—observing that the base of branches are dead—which is why the community of descent has become invisible, and why it will be defined as the hidden bond of the new genealogical arrangement. The same genealogical approach also emerges in the second (and today more famous) sketch by Darwin of the tree of life, drawn again in Notebook B, and emblematically “titled” I think. (Figure 2)

Figure 2.

Darwin, Notebook B—Transmutation of species (1837–1838), p. 36.

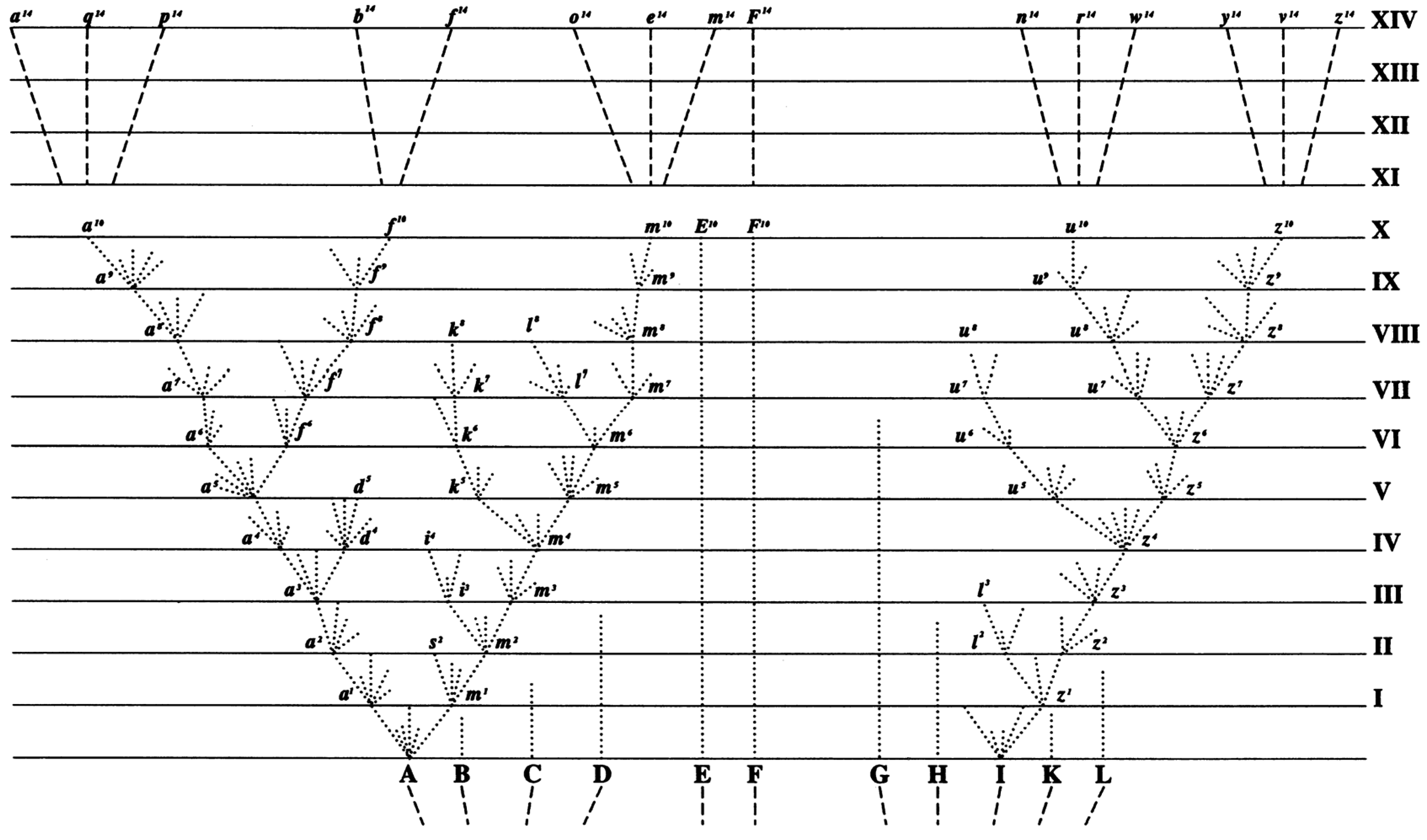

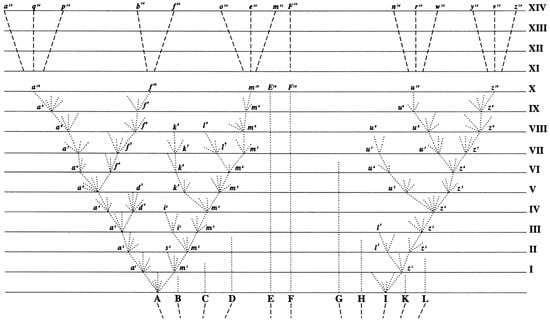

Here, Darwin again highlights the crucial role of extinction, explaining that, “to have many species in same genus (as is) requires extinction […]. Thus genera would be formed.—bearing relation to ancient types.—with several extinct forms”, and that the “death of species is a consequence […] of non-adaptation of circumstances.” (Darwin 1960, p. 36, emphasis mine)6. This theoretical model, which is able to account for the double process of adaptation/transformation and extinction/non-adaptation of the species, is the same model that Darwin will use as the basis for the theory expounded in his masterpiece On the Origin of Species (Darwin 1859–1876, p. 90). This model is visually depicted by the graph below. (Figure 3)

Figure 3.

Darwin, On the Origin of Species, p. 90.

Once again, Darwin presents us with a schematic of a genealogical tree (Darwin 1859–1876, p. 90)7, in which extinction plays a very important role (Darwin 1859–1876, pp. 92–93)8. Furthermore, we can read this graph not only from bottom to top, but also from top to bottom, in order to trace the lines of the supposed progenitor of the living (and also of the extinct) species (Darwin 1859–1876, p. 95). Now, the first general question that we could pose is: what are the mechanisms and forces that explain the becoming of new species, and the extinction of old species in this genealogical diagram? Darwin’s answer is that these processes are the “probable results of the action of natural selection through divergence of character and extinction, in the descendants of a common ancestor.” (Darwin 1859–1876, p. 95).

We should also consider the importance that Darwin gives to historical contingencies within his theoretical framework. Darwin explains, for example, that the general mechanism of the “process of modification” of the species, “will depend on many complex contingencies—on the variations being of a beneficial nature, on the freedom of intercrossing, on the slowly changing physical conditions of the country, on the immigration of new colonists, and on the nature of the other inhabitants with which the varying species come into competition”; at the same time, a fundamental role is played here by the presence of “variations or individual differences”: natural selection “works” on these differences (Darwin 1859–1876, p. 291)9. Here, Darwin directs our attention to the slow accumulation of very slight variations (Darwin 1859–1876, p. 404) that can be, and usually are, occasional.

In summary, Darwin’s genealogical tree shows that “all living and extinct organisms are united by complex, radiating, and circuitous lines of affinities”, with characters of “high or of the most trifling importance, or, as with rudimentary organs, of no importance”; it is a logical and necessary conclusion when “we admit the common parentage of allied forms, together with their modification through variation and natural selection, with the contingencies of extinction and divergence of character”; in other words, “if we extend the use of this element of descent,—the one certainly known cause of similarity in organic beings,—we shall understand what is meant by the Natural System: it is genealogical in its attempted arrangement, with the grades of acquired difference marked by the terms, varieties, species, genera, families, orders, and classes.” (Darwin 1859–1876, pp. 402–3). This theoretical framework is therefore not only genealogical, but also anti-teleological on several levels. The presence of useless parts shows that the process of modification does not work in any predetermined way, and that a function cannot always be found in the sense of an aim (or telos) for every part of every organic being.

This last point already offers the young Darwin a very strong argument to oppose the traditional teleological approach, expressed by the classical (Aristotelian) concept of a “final cause.” Although the young Darwin started to use the concept of “final cause” to conceive a mechanism that later leads to the concept of “natural selection” (Darwin 1960, p. 4910; 1987b, p. 23611; 1967, p. 13512), he soon showed a strong resistance to it. He explains, “The Final cause of innumerable eggs is explained by Malthus.—[is it anomaly in me to talk of Final causes: consider this?]—consider these barren Virgins.” (Darwin 1974). This reference to the Final causes in terms of barren Virgins is a quotation (through William Whewell) of Francis Bacon’s critique of the Aristotelian teleological framework (Bacon 1605, Chapter V, p. 168)13; (Whewell 1833, Chapter VII “On Final Causes”, p. 355)14; (Solinas 2015). The best argument used by the young Darwin against these barren Virgins was, however, the presence of rudimentary and useless organs. This argument emerges explicitly in Notebook E (1838–9):

“Who can say, how much structure is due to external agency, without final cause either in present or past generation—thus cabbages growing like Nepenthes—cases of pidgeons with tufts &c. &c. here there is no final cause yet it must be effect of some condition of external circumstances, results of complicated laws of organization […]. All that we can say in such cases is that the plumage has not been so injurious to bird as to allow any other kind of animal to usurp its place—& therefore the degree of injuriousness must have been exceedingly small.—This is far more probable way of explaining, much structure, than attempting anything about habits—No one can be shocked at absence of final cause. Mammae in man & wings under united elytra”.(Darwin 1987a, p. 147)

In short, the presence of rudimentary or useless parts is used by Darwin on a double level. On the negative side, they clearly show that the classical traditional teleological framework, understood also in the classical Aristotelian terms of “final cause”, not only cannot explain these parts, but it is actually invalidated and falsified by them. On the positive side, Darwin can claim that these rudimentary and useless organs can be explained only from a genealogical point of view: they offer another confirmation of his theory of descent with modification (Darwin 1859–1876, p. 402). Darwin’s theory is also, from this point of view, clearly anti-teleological (and anti-essentialist): there is no final cause.

2. Comparing Darwin and Foucault’s Genealogical Methods

Foucault’s genealogical research method outlined in his essay Nietzsche, Genealogy, History cannot be understood as a radical alternative to Darwin’s theory: on the contrary, it is partially referable to Darwin’s genealogical approach. There are obvious differences, however. Foucault’s methodology is focused on cultural-historical phenomena, whereas Darwin’s methodology is concerned with naturalistic phenomena. Foucault’s genealogy is also more abstract, and it has several peculiar features that have no relevance for Darwin’s naturalistic theoretical framework. However, Foucault’s genealogical methodology shows some affinities with Darwin’s approach, first of all because he ascribes to it, via Nietzsche, a clear and strong anti-essentialist and anti-teleological character. For Foucault (as for Darwin), there isn’t any “essence” at stake, there isn’t any predetermined form or aim, and there isn’t any final cause.

Despite this anti-teleological character, Foucault develops a clear differentiation between evolutionism and genealogy. To overcome the misleading impression that Foucault’s critique of “evolutionism” could and should be addressed directly to Darwin, we should note that when Foucault dismisses what he calls “evolutionism”, he writes that genealogies “must record the singularity of events outside of any monotonous finality […]; it must be sensitive to their recurrence, not in order to trace the gradual curve of their evolution, but to isolate the different scenes where they engaged in different roles.” (Foucault 1971, pp. 139–40, emphasis mine). Foucault then concludes: genealogy “rejects the metahistorical deployment of ideal significations and indefinite teleologies [indéfinies téléologies]. It opposes itself to the search for ‘origins’ [Elle s’oppose à la recherche de l’“origine”]” (Foucault 1971, pp. 139–40). In other words, Foucault establishes (via Nietzsche) not only a differentiation, but actually an opposition between a method based on a teleological form of evolution with finality (finalité) that aims to find the origin on the one hand, and a method focused on the singularity of events analysed by a non-teleological genealogy (Foucault 1969, p. 31)15. The teleological method has a continuity and a predetermined aim; on the contrary, genealogy has to do with historical processes that do not have any predetermined aim and form, and for which it is always possible to find not one single origin, but “numberless beginnings.” For Foucault, the process of tracing these “numberless beginnings” requires an analysis that can account for contingency, accidents, and chance (Domenicali 2006, pp. 110–11). As he explains:

“Where the soul pretends unification or the self fabricates a coherent identity, the genealogist sets out to study the beginning—numberless beginnings [des commencements innombrables] whose faint traces and hints of color are readily seen by an historical eye […]. The analysis of descent permits the dissociation of the self, its recognition and displacement as an empty synthesis, in liberating a profusion of lost events. An examination of descent also permits the discovery, under the unique aspect of a trait or a concept, of the myriad events through which—thanks to which, against which—they were formed. Genealogy does not pretend to go back in time to restore an unbroken continuity that operates beyond the dispersion of forgotten things; its duty is not to demonstrate that the past actively exists in the present, that it continues secretly to animate the present, having imposed a predetermined form [une forme dessinée dès le départ] to all its vicissitudes. Genealogy does not resemble the evolution of a species and does not map the destiny of a people [Rien qui ressemblerait à l’évolution d’une espèce, au destin d’un peuple]. On the contrary, to follow the complex course of descent [la filière complexe de la provenance] is to maintain passing events in their proper dispersion; it is to identify the accidents, the minute deviations—or conversely, the complete reversals—the errors, the false appraisals, and the faulty calculations that gave birth to those things that continue to exist and have value for us; it is to discover that truth or being do not lie at the root of what we know and what we are, but the exteriority of accidents [l’extériorité de l’accident]”.(Foucault 1971, pp. 145–46)

Darwin’s natural genealogies can also be explained by a theoretical framework that is not only non-teleological, but also anti-teleological. One example of this anti-teleological orientation is Darwin’s understanding that the becoming and extinction of species is allowed by several contingencies that operate through the relations between an organic being and its environment, and also through the divergence of character within the species. This view of “evolution” demonstrates a strong convergence with Foucault’s understanding of the myriad of events that compose a genealogy (Foucault 1971, pp. 144–45, 154)16; it also highlights an affinity in the role that “events” (by Foucault) and “contingencies” (by Darwin) play in their respective genealogies. It is worth noting that Foucault eventually uses the term contingency in conjunction with his genealogical method, as illustrated by his essay, What is Enlightenment? (Foucault 1984, p. 46)17.

Darwin’s examination of contingency also leads him to develop explanations that parallel Foucault’s interest in using his genealogical method to trace “numberless beginnings”. A good example is Darwin’s appreciation for nonlinear and diverging (or broken) lines of descent—a “filière complexe de la provenance”—which leads to the idea of there being several beginnings. He explains: “We possess no pedigrees or armorial bearings; and we have to discover and trace the many diverging lines of descent in our natural genealogies, by characters of any kind which have long been inherited.” (Darwin 1859–1876, p. 427). This means that every single living or dead species has innumerable beginnings, because the common parent(s) has become (usually) extinct. In other words, every species descends from a different species, and if we go further into its genealogy, we find different beginnings, and not just different individuals of the same species, as happens in the traditional armorial bearings of a family genealogy: we have to do with old genera, families, and so on; natural genealogies are not limited to the “evolution of a species”.

Hence, if it’s true that “all the individuals of the same species, and all the closely allied species of most genera, have […] descended from one parent”, it does not mean that this “parent” represents the “origin” in the sense “that the past actively exists in the present, that it continues secretly to animate the present, having imposed a predetermined form [une forme dessinée dès le départ] to all its vicissitudes”. What’s true is exactly the opposite: there isn’t any “predetermined form”. The process of descent is totally unpredictable. There are “innumerable beginnings” of a living species: first of all, on the level of the micro and accidental individual variations that can slowly give rise to the birth of new species, and then on the level of several “old” species; we also have to do with the many “old parents” that are usually (but not always) extinct. At this macro-level, we therefore do not have to do with a simple, fixed, and pre-established “evolutionary curve” of the species (Foucault 1972, p. 420)18, but with “many diverging lines of descent”. These levels are furthermore always connected with the totally unpredictable and fortuitous changes and transformations of the environment. If then Darwin adopted a gradualist vision, that is certainly significantly different from Foucault’s view (Foucault 1972, p. 431)19 by Darwin there isn’t anyway any essence or form of the species that is given from its “origin”, and there isn’t any predetermined pattern or form of his “evolution”—using Foucault’s terms, here we have to speak not of one single essentialist Ursprung, but of numberless Entstehungen. In short, Darwin’s theoretical framework of natural genealogies represents a clear alternative to the traditional philosophical (and metaphysical) model of a teleological and essentialist (and fixed) arrangement of the species. This is an alternative, even in a very peculiar way, to the conceptual model that, in Foucault’s term, is defined as being based on the idea of a teleological reason or logos.

In Darwin’s theory, divergences of genealogical lines are produced by complex contingencies, and genealogical research—examining the innumerable dead branches of the tree of life—has to trace extinctions (Darwin 1859–1876, p. 419)20. Here, the principle of extinction also draws attention to a multiplicity of invisible conflicts. Darwin remarks: “It is most difficult always to remember that the increase of every creature is constantly being checked by unperceived hostile agencies; and that these same unperceived agencies are amply sufficient to cause rarity, and finally extinction.” (Darwin 1859–1876, p. 295, emphasis mine). Darwin highlights that we “need not marvel at extinction; if we must marvel, let it be at our own presumption in imagining for a moment that we understand the many complex contingencies on which the existence of each species depends.” (Darwin 1859–1876, p. 297, emphasis mine). In the new economy of nature, dominated by several contingencies and conflicts undergoing constant change, as natural species are, the relationship between existence and extinction is overturned. The (incontrollable) pressure of external factors also plays a vital (and a fatal) role at the level of single organisms. At the same time, unperceived hostile agencies, as well as the possibility of “fortuitous destruction” determined by “accidental causes” (Darwin 1859–1876, p. 68), finds a counterpart in the individual slight variations and changes that can arise “suddenly or by one step”, and “occasionally.” (Darwin 1859–1876, pp. 22, 28). These “single and occasional variations” that can be called “individual differences” (Darwin 1859–1876, p. 34) are a driving force behind the process of descent with modification, allowing the species to adapt and avoid extinction. Hence, Darwin treats the singularity of occasional slight events with the “highest importance”—finding them of great theoretical significance (Darwin 1859–1876, p. 34)21. According to Darwin, occasional slight variations always have to be considered “in their infinitely complex relations to other organic beings and to their physical conditions of life” (Darwin 1859–1876, pp. 49, 62)22. It seems to me that this way of explaining the single and occasional variations on the basis of natural genealogies could also be understood in terms of Foucault’s accidents and minute deviations of the complex of the course of descent (Foucault 1971, pp. 145–46); it is also important to consider the significance that Foucault attributes to bodies (Foucault 1971, p. 148)23 (Flynn 2005, especially pp. 34 ff., 39–41)24: a concern that is pertinent to Darwin’s thematization of organisms.

Furthermore, the presence of rudimentary and useless organs, being parts of the body without any aim and utility, clearly shows that the process of descent with modification does not have any predetermined form and aim, and Darwin uses these parts as proof of the “absence of final cause” (Darwin 1987a, p. 147). Foucault’s critique of teleology is also directed (via Nietzsche) at final cause; he explains: “the world of effective history knows only one kingdom, without providence or final cause [où il n’y a ni providence ni cause finale], where there is only ‘the iron hand of necessity shaking the dice-box of chance [le cornet du hasard]’.” (Foucault 1971, p. 155)25. Foucault later highlights the point: “The objectivity of historians inverts the relationships of will and knowledge and it is, in the same stroke, a necessary belief in Providence, in final causes and teleology—the beliefs that place the historian in the family of ascetics.” (Foucault 1971, p. 14)26.

Another important and strong point of convergence with Darwin concerns Foucault’s (and Nietzsche’s) radical anti-essentialism, which is well illustrated by the following passage: “Why does Nietzsche challenge the pursuit of the origin (Ursprung), at least on those occasions when he is truly a genealogist? First, because it is an attempt to capture the exact essence of things [l’essence exacte de la chose], their purest possibilities, and their carefully protected identities, because this search assumes the existence of immobile forms that precede the external world of accident and succession [sa forme immobile et antérieure à tout ce qui est externe, accidentel et successif]” (Foucault 1971, p. 142). Here, we are clearly faced with the same theoretical model that was the basis of the traditional Natural System that Darwin’s historical genealogies had to overcome and substitute. One basis of the old naturalistic framework was that the species were “immobile forms”; and the concept of “form” was at the same time understood (in Aristotelian terms) as immutable “essence”. In this regard, there is total agreement between the two genealogical frameworks, in opposition to the traditional metaphysical (Aristotelian) essentialistic approach; and this is a point that is actually crucial for Foucault’s methodology (Davidson 1986, p. 224)27.

Foucault’s critique of the solennités de l’origine, and praise of the lowliness of historical beginnings, illustrates another agreement between Foucault’s (and Nietzsche’s) genealogy and Darwin’s natural genealogy. Foucault explains:

“History also teaches how to laugh at the solemnities of the origin. The lofty origin is no more than ‘a metaphysical extension which arises from the belief that things are most precious and essential at the moment of birth’ (Nietzsche, The Wanderer and his Shadow). We tend to think that this is the moment of their greatest perfection, when they emerged dazzling from the hands of a creator or in the shadowless light of a first morning. The origin always precedes the Fall. It comes before the body, before the world and time; it is associated with the gods, and its story is always sung as a theogony. But historical beginnings are lowly [Mais le commencement historique est bas]: not in the sense of modest or discreet like the steps of a dove, but derisive and ironic, capable of undoing every infatuation. ‘We wished to awaken the feeling of man’s sovereignty by showing his divine birth: this path is now forbidden, since a monkey stands at the entrance’ (Nietzsche, The Dawn). Man originated with a grimace over his future development”.(Foucault 1971, p. 143)

Now, if there are so many convergences and agreements between the two genealogical frameworks, why does Foucault insist on an opposition between evolutionism and genealogy? An initial response can be found in his several interpretations of the meaning of the terms “evolutionism” presented not only in his essay Nietzsche, Genealogy, History, but also in the other important works of the Sixties. Foucault had already partially developed the concepts of “evolution”, “evolutionism”, and “quasi-evolutionism” in The Order of Things and then in The Archaeology of Knowledge. Yet, in The Order of Things, Foucault differentiates between the concepts of “evolution” and “evolutionism” before and after Darwin. He starts with Charles Bonnet’s (1720–1793) system in which “’evolution’ is understood as the interdependent and general displacement of the whole scale from the first of its elements to the last”, and in which “’evolutionism’ is […] a way of generalizing the principle of continuity and the law that requires that all beings form an uninterrupted expanse.” (Foucault 1966, p. 165). Foucault criticizes Bonnet’s model and concludes that we need a theory that is “as far removed as possible from what we understand, since the nineteenth century, by ‘evolutionism.’” (Foucault 1966, p. 166). Foucault also comments on a second “form of ‘evolutionism’”: that of Benoît de Maillet, which can be defined as a “quasi-evolutionism.” Foucault explains: “The quasi-evolutionism of the eighteenth century seems to presage equally well the spontaneous variation of character, as it was later to be found in Darwin, and the positive action of the environment, as it was described by Lamarck. But this is an illusion of hindsight: for this form of thought, in fact, the sequence of time can never be anything but the line along which all the possible values of the pre-established variables succeed one another.” (Foucault 1966, p. 127). It means that, differently from Darwin, despite the illusion of hindsight, this “quasi-evolutionism” has a pre-established temporality. We also have to face the question posed by Foucault’s peculiar interpretation of Cuvier. Despite Cuvier’s “fixist” theory of the species, Foucault observes that he developed an approach—with an appreciation for “discontinuity” (Foucault 1966, p. 300)28—that should lead to Darwin, and against Lamarck’s teleological approach to evolutionism (Foucault 1966, pp. XXIV, 167ff., 299ff., 319–20); (Flynn 2005, p. 8f)29. This observation confirms that Foucault was fully aware of the fundamental differences between quasi-evolutionism, teleological evolutionism, and Darwin’s theory.

However, it seems to me that later in The Archaeology of Knowledge, the distinction between the different historical meanings of the concept of “evolution” and “evolutionism” plays a weaker role in Foucault’s genealogical method. In other words, Foucault seems to become more critical of the whole constellation of concepts linked to “evolution.” Sometimes, he speaks of the “notions of development and evolution” without distinguishing which type of “evolution” is at stake (Foucault 1969, pp. 24, 28, 157–58, 191, 230)30, and often this concept (e.g., the “evolutive curves”) is associated with “teleologies” and “origins” from the general point of view of history tout court (that is, not only of the history of biology) (Foucault 1969, p. 13)31. The same applies with respect to the convergence between the “essential nucleus of interiority”, the “evolution of mentalities”, and “the recollection of the Logos or the teleology of reason.” (Foucault 1969, p. 136). In short, we are faced with a critique of teleology that makes no distinctions between different evolutionary theories (Foucault 1969, p. 141)32.

Foucault explains: “To the decentering operated by the Nietzschean genealogy, it [the old approach] opposed the search for an original foundation that would make rationality the telos of mankind [il a oppose la recherché d’un fondement originaire qui fasse de la rationalité le telos de l’humanité], and link the whole history of thought to the preservation of this rationality, to the maintenance of this teleology [au maintien de cette téléologie], and to the ever necessary return to this foundation” (Foucault 1969, p. 14). Here, Foucault insists that we must work against the attempt “to interpret Nietzsche in the terms of transcendental philosophy, and avoid reducing his genealogy to a search for origins [et a rabattre sa généalogie sur le plan d’une recherché de l’originaire].” (Foucault 1969, p. 15). In this book Foucault reaffirms the basic distinction between the “evolutionist idea” in the eighteenth century, and the “evolutionist theme” in the nineteenth century, also explaining that the first referred to a “continuum” and the latter to “discontinuous groups.” (Foucault 1969, pp. 39–40, especially p. 40)33. However, he also uses the term “evolutionist” for both historical movements (sometimes without enclosing his references to eighteenth century evolutionist theory within single quotation marks, as he did in The Order of Things); we have always to do with forms of “evolutionism” (Foucault 1969, pp. 169–70, 71, 116–17, 159–60)34.

It seems that from The Order of Things, to The Archaeology of Knowledge, and finally Nietzsche, Genealogy, History, Foucault’s approach to “evolutionism” becomes more critical (Foucault 1972, pp. 419–20). He strengthens his emphasis on the problems with the teleological assumptions of the “evolutionistic” search for the “origin.” At the same time, Foucault seems to always be aware of the complexity and importance of Darwin’s theory from a genealogical point of view. Foucault conveys this viewpoint in two ways. The first is from a “negative” point of view. Despite the opposition between genealogy and evolutionism that Foucault (re-)establishes in Nietzsche, Genealogy, History, he never quotes the name of Darwin as an example of the teleological view point that he dismisses. The second way that Foucault conveys his appreciation for Darwin is from a “positive” point of view. In this case, we should consider a short essay published in 1970 (La situation de Cuvier dans l’histoire de la biologie) in which Foucault establishes an explicit connection between Darwin and the concept of “genealogy”, explaining that “he will show how, beginning with the individual, what will be established as its species, its order, or its class will be the reality of its genealogy: a succession of individuals.” (Foucault 1970, p. 212)35

In conclusion, I believe that the opposition Foucault establishes between genealogy and evolutionism, as presented in his essay Nietzsche, Genealogy, History is, if referred to Darwin, misleading. It is misleading first of all because it overlooks the strong anti-teleological and anti-essentialist character of Darwin’s theory. However, it is also misleading because it seems to ignore the importance that Darwin gives to accidental and micro factors at the individual level, and more generally, to the fortuities, singular and unpredictable factors connected to the (complex) processes of extinction and the forming of new species. However, Foucault’s criticism is misleading above all, because it seems to overlook that it was Darwin (Nietzsche arrived only after him) with his extraordinary cultural-scientific revolution of biology, who gave the concept of genealogy a crucial role, as an explanatory framework, from a historical point of view.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References and Notes

- Archibald, David J. 2014. Aristotle’s Ladder, Darwin’s Tree: The Evolution of Visual Metaphor for Biological Order. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- An important previous work is Peter Atterton. Atterton, Peter. 1994. Power’s Blind Struggle for Existence: Foucault, Genealogy and Darwinism. In History of the Human Sciences. vol. 7, pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar], but here the focus is on the role of the selection and on the topic of bio-power and bio-history.

- Bacon, Francis. 1605. Of the Dignity and Advancement of Learning. London: Longman, Book III. [Google Scholar]

- For a more comprehensive analysis of Darwin’s use of the image of the tree of life, his relations with other traditional biological images, starting from the traditional scala naturae and so on, see Barsanti, Giulio. 1992. La Scala, la Mappa e L’albero. Florence: Sansoni. [Google Scholar]

- Darwin, Charles R. 1859–1876. The Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life, 6th ed. London: Murray, with additions and corrections. [Google Scholar]

- The German translation of the word "origin" used by Darwin in his book The Origin of Species is in fact often (included the title) Entstehung and sometimes also Ursprung, see the 1876 German edition: 1876, Darwin, Charles R. Über die Entstehung der Arten durch natürliche Zuchtwahl oder die Erhaltung der begünstigten Rassen im Kampfe um’s Dasein, 6th ed. Translated by Heinrich Georg Bronn, and J. Victor Carus. Stuttgart: Schweizerbart. [Google Scholar]. where for example the paragraph An historical Sketch oft he Progress of Opinion on the Origin of Species Previously to the Publication of the First Edition of this Work, is translated as follows: Historische Skizze der neueren Fortschritte in den Ansichten über den Ursprung der Arten.

- Darwin, Charles R. 1960. Notebook B—Transmutation of species (1837–1838). In Charles Darwin’s Notebooks. Edited by Paul H. Barrett, Peter Jack Gautrey, Sandra Herbert and David Kohn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 21–26, emphasis mine. Available online: www.darwin-online.org.uk (accessed on 22 May 2017).

- Darwin, Charles R. 1987a. Notebook E, Transmutation of Species (1838–1839). In Charles Darwin’s Notebooks. Edited by Paul H. Barrett, Peter Jack Gautrey, Sandra Herbert and David Kohn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 147. [Google Scholar]

- Darwin, Charles R. 1987b. Notebook C—Transmutation of Species (1838.02–1838.07). In Charles Darwin’s Notebooks. Edited by Paul H. Barrett, Peter Jack Gautrey, Sandra Herbert and David Kohn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 236. [Google Scholar]

- Darwin, Charles R. 1967. Notebook D—Transmutation of species (1838). Bulletin of the British Museum 3: 129–76. [Google Scholar]

- Darwin, Charles R. 1974. Macculloch. Attrib of Deity, Essay on Theology and Natural Selection. In Darwin on Man. Edited by Howard E. Gruber. London: Wildwood, Available online: http://darwin-online.org.uk (accessed on 22 May 2017).

- See for example the classical Davidson, Arnold I. 1986. Archaeology, Genealogy, Ethics. In Foucault: A Critical Reader. Edited by David C. Hoy. Oxford and New York: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- On this point see e.g., Domenicali, Filippo. 2006. La traccia quasi cancellata. Il metodo genealogico di Foucault. I Castelli di Yale VIII: 107–16. [Google Scholar]

- Flynn, Thomas. 2005. Foucault’s Mapping History. In The Cambridge Companion to Foucault. Edited by Gary Gutting. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, Michel. 1966. Les Mots et les Choses. Paris: Gallimard. [Google Scholar] English Transl.: The Order of Things. An Archaeology of the Human Sciences. New York and London: Routledge. Translated in 2002–2005.

- Foucault, Michel. 1969. L’Archéologie du Savoir. Paris: Gallimard. [Google Scholar] English Transl.: The Archaeology of Knowledge. 2002. London and New York: Routledge.

- Foucault, Michel. 1970. La situation de Cuvier dans l’histoire de la biologie. Revue d’histoire des Sciences et de Leurs Applications XXIII: 63–92. [Google Scholar] English Transl.: 2017. Cuvier’s Situation in the History of Biology. Foucault Studies 22: 208–37.

- Foucault, Michel. 1971. Nietzsche, la généalogie, l’histoire. In Hommage à Jean Hyppolite. Paris: P.U.F., pp. 145–72. [Google Scholar] English Transl.: Nietzsche, Genealogy, History. 1977, In Language, Counter-Memory, Practice. Foucault, Michel. Edited by Donald F. Bouchard. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, Michel. 1972. Rekishi heno kaiki. Paideia 11: 45–60. [Google Scholar] French transcription reviewed by Foucault: Revenir à l’histoire. 2001, In Dits et Écrits. I, 1954–1975. Paris: Gallimard. English Transl.: Return to History. 1998, In Aesthetics, Method, and Epistemology. Faubion, James D., ed. New York: The New Press. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, Michel. 1984. Qu’est-ce que les Lumières? [Google Scholar] English Transl.: What is Enlightenment? In The Foucault Reader. Rabinow, Paul, ed. New York: Pantheon, p. 46.

- Johnson, Dirk R. 2010. Nietzsche’s Anti-Darwinism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Koopman, Colin. 2013. Genealogy as Critique. Foucault and the Problem of Modernity. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mahon, Michael. 1992. Foucault’s Nietzschean Genealogy. Truth, Power and the Subject. New York: SUNY. [Google Scholar]

- Fort the instances of the use of the original terms Ursprung, Herkunft und Entstehungsgeschichte see Nietzsche, Friedrich. 1892. Zur Genealogie der Moral. Eine Streitschrift. Leipzig: Neumann, zweite Auflage, especially. pp. IV–IX, 3–6, 8, 18, 26, 43, 46, 48, 58, 62, 66, 67, 76, 78, 79, 82, 84, 89, 101, 107, 116, 155. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, John. 2004. Nietzsche’s New Darwinism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Saar, Martin. 2007. Genealogie als Kritik. Geschichte und Theorie des Subjekts nach Nietzsche und Foucault. Frankfurt and Main: Campus. [Google Scholar]

- Sarasin, Philipp. 2009. Darwin und Foucault. Genealogie und Geschichte im Zeitalter der Biologie. Frankfurt and Main: Suhrkamp, in particularly chapter 7. pp. 222–63. [Google Scholar]

- I have outlined the general question in Solinas, Marco. 2015. From Aristotle’s Teleology to Darwin’s Genealogy. London and New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Whewell, William. 1833. On Astronomy and General Physics Considered with Reference to Natural Theology, II ed. London: Pickering, Book III. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | “As all the organic beings, extinct and recent, which have ever lived, can be arranged within a few great classes; and as all within each class have, according to our theory, been connected together by fine gradations, the best, and, if our collections were nearly perfect, the only possible arrangement, would be genealogical; descent being the hidden bond of connexion which naturalists have been seeking under the term of the Natural System.” |

| 2. | “We use the element of descent in classing the individuals of both sexes and of all ages under one species, although they may have but few characters in common; we use descent in classing acknowledged varieties, however different they may be from their parents; and I believe that this element of descent is the hidden bond of connexion which naturalists have sought under the term of the Natural System. On this idea of the natural system being, in so far as it has been perfected, genealogical in its arrangement, with the grades of difference expressed by the terms genera, families, orders, &c., we can understand the rules which we are compelled to follow in our classification. We can understand why we value certain resemblances far more than others; why we use rudimentary and useless organs, or others of trifling physiological importance; why, in finding the relations between one group and another, we summarily reject analogical or adaptive characters, and yet use these same characters within the limits of the same group.”, emphasis mine. |

| 3. | where there is a deep comparison of Foucault’s genealogy and Darwin’s genealogical method. |

| 4. | “Organized beings represent a tree irregularly branched some branches far more branched—Hence Genera.—) As many terminal buds dying as new ones generated. There is nothing stranger in death of species than individuals If we suppose monad definite existence, as we may suppose in this case, their creation being dependent on definite laws, then those which have changed most owing to the accident of positions must in each state of existence have shortest life. Hence shortness of life of Mammalia. Would there not be a triple branching in the tree of life owing to three elements air, land & water, & the endeavour of each typical class to extend his domain into the other domains, and subdivision three more, double arrangement.—if each main stem of the tree is adapted for these three elements, there will be certainly points of affinity in each branch […]. We need not think that fish & penguins really pass into each other.—The tree of life should perhaps be called the coral of life, base of branches dead; so that passages cannot be seen. —this again offers contradiction to constant succession of germs in progress”. |

| 5. | After the quoted passage, Darwin drew a first sketch and writes: “is it thus fish can be traced right down to simple organization. birds—Not.”; then Darwin drew a second sketch; see the reproduction of page 26 of the Notebook B, cit. |

| 6. | “Case must be that one generation then should be as many living as now. To do this & to have many species in same genus (as is) requires extinction. Thus between A & B immense gap of relation. C & B the finest gradation, B & D rather greater distinction. Thus genera would be formed.—bearing relation to ancient types.—with several extinct forms for if each species an ancient (1) is capable of making 13 recent forms [In the diagram there are 13 lines that have a perpendicular line at the end], twelve of the contemporaries must have left no offspring at all [In the diagram there are 12 lines that are without a perpendicular line at the end], so as to keep number of species constant.—With respect to extinction we can easy see that variety of ostrich, Petise may not be well adapted, and thus perish out, or on other hand like Orpheus being favourable many might be produced.—This requires principle that the permanent varieties produced by confined breeding & changing circumstances are continued & produced according to the adaptation of such circumstances, & therefore that death of species is a consequence (contrary to what would appear from America) of non-adaptation of circumstances”, source of the reproduction: The Complete Works of Charles Darwin. Available online: www.darwin-online.org.uk. |

| 7. | Darwin, at the same time, highlights that he does “not suppose that the process ever goes on so regularly as is represented in the diagram, though in itself made somewhat irregular, nor that it goes on continuously; it is far more probable that each form remains for long periods unaltered, and then again undergoes modification”. |

| 8. | “But during the process of modification, represented in the diagram, another of our principles, namely that of extinction, will have played an important part. As in each fully stocked country natural selection necessarily acts by the selected form having some advantage in the struggle for life over other forms, there will be a constant tendency in the improved descendants of any one species to supplant and exterminate in each stage of descent their predecessors and their original progenitor. For it should be remembered that the competition will generally be most severe between those forms which are most nearly related to each other in habits, constitution, and structure. Hence all the intermediate forms between the earlier and later states, that is between the less and more improved states of the same species, as well as the original parent-species itself, will generally tend to become extinct. So it probably will be with many whole collateral lines of descent, which will be conquered by later and improved lines. If, however, the modified offspring of a species get into some distinct country, or become quickly adapted to some quite new station, in which offspring and progenitor do not come into competition, both may continue to exist” |

| 9. | “the process of modification must be slow, and will generally affect only a few species at the same time; for the variability of each species is independent of that of all others. Whether such variations or individual differences as may arise will be accumulated through natural selection in a greater or less degree, thus causing a greater or less amount of permanent modification, will depend on many complex contingencies—on the variations being of a beneficial nature, on the freedom of intercrossing, on the slowly changing physical conditions of the country, on the immigration of new colonists, and on the nature of the other inhabitants with which the varying species come into competition.”, emphasis mine. |

| 10. | “Progressive development gives final cause for enormous periods anterior to man”. |

| 11. | “I can scarcely doubt final cause is the adaptation of species to circumstances by principles, which I have given”. |

| 12. | “– The final cause of all this wedging, must be to sort out proper structure, & adapt it to changes.—to do that for form, which Malthus shows is the final effect (by means however of volition) of this populousness on the energy of man. One may say there is a force like a hundred thousand wedges trying force into [sic] every kind of adapted structure into the gaps of [sic] in the oeconomy of nature, or rather forming gaps by thrusting out weaker ones”. |

| 13. | “THE practical doctrine of nature we likewise necessarily divide into two parts, corresponding to those of speculative; for physics, or the inquiry of efficient and material causes produces mechanics; and metaphysics, the inquiry of forms, produces magic; while the while the inquiry of final causes is a barren thing, or as a virgin consecrated to God”. |

| 14. | “Bacon’s comparison of final causes to the vestal virgins is one of those poignant sayings, so frequent in his writings, which it is not easy to forget. ‘Like them,’ he says, ‘they are dedicated to God, and are barren.’ But to any one who reads his work it will appear in what spirit this was meant. ‘Not because those final causes are not true and worthy to be inquired, being kept within their own province.’ (Of the Advancement of Learning, b. ii, p. 142.)”. |

| 15. | On the singularity and emergence (a the methodological level) see, e.g., also (Foucault 1969, p. 31): “In fact, the systematic erasure of all given unities enables us first of all to restore to the statement the specificity of its occurrence, and to show that discontinuity is one of those great accidents that create cracks not only in the geology of history, but also in the simple fact of the statement; it emerges in its historical irruption; what we try to examine is the incision that it makes, that irreducible—and very often tiny—emergence.” |

| 16. | “He must be able to recognize the events of history, its jolts, its surprises, its unsteady victories and unpalatable defeats—the basis of all beginnings, atavisms, and heredities”; and p. 154: “An event [Événement], consequently is not a decision, a treaty, a reign, or a battle, but the reversal of a relationship of forces, […]. The forces operating in history are not controlled by destiny or regulative mechanism, but respond haphazard conflicts [mais bien au hasard de la lutte] (The Genealogy, II, 12)”. |

| 17. | “And this critique will be genealogical in the sense that it will not deduce from the form of what we are what it is impossible for us to do and to know; but it will separate out, from the contingency that has made us what we are, the possibility of no longer being, doing, or thinking what we are, do, or think. It is not seeking to make possible a metaphysics that has finally become a science; it is seeking to give new impetus, as far and wide as possible, to the undefined work of freedom”, emphasis mine. |

| 18. | “This history assumed that human society all follow the same evolutionary curve, going from the simplest forms to the most complex. The evolution did not vary from one society to another except in the speed of transformations. Further, the great social forms such as marriage rules or agricultural techniques were seen basically as kinds of biological species, and their extensions, their growth, their development, and their distribution were thought to obey the same laws and patterns as the growth and spread of biological species. In any case, the model that Tylor used to analyze the development and history of societies was the biological one. Tylor referred to Darwin, and more generally to evolutionism, in order to tell the story of societies.” |

| 19. | “And just as there is no violent revolution in life, but simply a slow accumulation of tiny mutations, in the same way human history cannot really have the potential for a violent revolution; it can never harbor within itself anything more than imperceptible changes. By metaphorizing history on the analogy of life, one thus guaranteed that human societies would be incapable of a revolution. I think that structuralism and history make it possible to abandon this great biological mythology of history and duration. Structuralism, by defining transformations, and history, by descripting types of events and different types of duration, make possible both the appearance of discontinuities in history and the appearance of regular, coherent transformations.” |

| 20. | “The Natural System is a genealogical arrangement, with the acquired grades of difference, marked by the terms, varieties, species, genera, families, etc.; and we have to discover the lines of descent by the most permanent characters whatever they may be and of however slight vital importance.” |

| 21. | “The many slights differences which appear in the offspring from the same parents, or which it may be presumed have thus arisen, from being observed in the individuals of the same species inhabiting the same confined locality, may be called individual differences. No one supposes that all individuals of the same species are cast in the same actual mould. These individual differences are of the highest importance for us, for they are often inherited, as must be familiar to every one […]. These individual differences generally affect what naturalists consider unimportant parts; but I could show by a long catalogue of facts, that parts which must be called important, whether viewed under a physiological or classificatory point of view, sometimes vary in the individuals of the same species.” |

| 22. | “[…] similar changes of conditions might and do occur under nature. Let it also be borne in mind how infinitely complex and close-fitting are the mutual relations of all organic beings to each other and to their physical conditions of life; and consequently what infinitely varied diversities of structure might be of use to each being under changing conditions of life.” |

| 23. | “The body—and everything that touches it: diet, climate, and soil—is the domain of the Herkunft. The body manifests the stigmata of past experience and also gives rise to desires, failings, and errors.” |

| 24. | On the relevance of the bodies and of the singular randomness of events see e.g., Thomas Flynn. Foucault’s Mapping History. |

| 25. | The end citation is taken from Nietzsche’s The Dawn. |

| 26. | “To the decentering operated by the Nietzschean genealogy, it opposed the search for an original foundation that would make rationality the telos of mankind, and link the whole history of thought to the preservation of this rationality, to the maintenance of this teleology, and to the ever necessary return to this foundation”. |

| 27. | “Yet what is distinctive about genealogy is not its interest in origins, but the form its interest takes, and the kind of origins it isolates for analysis. Genealogy does not look to origins to capture the essence of things, or to search for some ‘immobile form’ that has developed throughout history; the secret disclosed by genealogy is that there is no essence or original unity to be discovered. When genealogy looks to beginnings, it looks for accidents, chance, passion, petty malice, surprises, feverish agitation, unsteady victories, and power. As Foucault says in his essay on Nietzsche, a crucial essay in understanding his own thought, ‘historical beginnings are lowly […].” |

| 28. | “What makes Lamarck’s thought possible is not the distant apprehension of a future evolutionism; it is the continuity of beings as discovered and presupposed by the ‘methods’ of natural history. Lamarck is a contemporary of A-L. de Jussieu, not of Cuvier. For the latter introduced a radical discontinuity into the Classical scale of beings; and by that very fact he gave rise to such notions as biological incompatibility, relations with external elements, and conditions of existence; he also caused the emergence of a certain energy, necessary to maintain life, and a certain threat, which imposes upon it the sanction of death; here, we find gathered together several of the conditions that make possible something like the idea of evolution. The discontinuity of living forms made it possible to conceive of a great temporal current for which the continuity of structures and characters, despite the superficial analogies, could not provide a basis. With spatial discontinuity, the breaking up of the great table, and the fragmentation of the surface upon which all natural beings had taken their ordered places, it became possible to replace natural history with a ‘history’ of nature.” |

| 29. | “Foucault makes a similar use of the history of concepts in The Order of Things when he argues that the Darwinian idea of an evolution of species is implicit in Cuvier but not in Lamarck. […] Foucault argues, it is Cuvier and not Lamarck who introduces the fundamental idea that biological species are productions of historical forces rather than instantiations of timeless, a priori possibilities. Lamarckian “evolution” is merely a matter of living things successively occupying preestablished niches that are quite independent of historical forces, such as natural selection. […] Lamarckian change is just a superficial play of organisms above the eternally fixed structure of species; Cuvier’s fixism is a historical stability produced by radically temporal biological processes. Accordingly, Foucault maintains that Cuvier rather than Lamarck provides the conceptual framework that makes Darwin’s theory of evolution possible.” |

| 30. | “There are the notions of development and evolution: they make it possible to group a succession of dispersed events, to link them to one and the same organizing principle, to subject them to the exemplary power of life (with its adaptations, its capacity for innovation the incessant correlation of its different elements, its systems of assimilation and exchange), to discover, already at work in each beginning, a principle of coherence and the outline of a future unity, to master time through a perpetually reversible relation between an origin and a term that are never given, but are always at work.”; see also here p. 28: “It may be, for example, that the notions of ‘influence’ or ‘evolution’ belong to a criticism that puts them—for the foreseeable future—out of use.”; see also here pp. 157–58 on “the continuous line of an evolution”; and p. 183 on the “schemata of evolution”, then pp. 191, 230. |

| 31. | “As if, in that field where we had become used to seeking origins, to pushing back further and further the line of antecedents, to reconstituting traditions, to following evolutive curves, to projecting teleologies, and to having constant recourse to metaphors of life, we felt a particular repugnance to conceiving of difference, to describing separations and dispersions, to dissociating the reassuring form of the identical”. |

| 32. | “to describe a group of statements, in order to rediscover not the moment or the trace of their origin, but the specific forms of an accumulation, is certainly not to uncover an interpretation, to discover a foundation, or to free constituent acts; nor is it to decide on a rationality, or to embrace a teleology”. |

| 33. | “In the eighteenth century, the evolutionist idea is defined on the basis of a kinship of species forming a continuum laid down at the outset (interrupted only by natural catastrophes) or gradually built up by the passing of time. In the nineteenth century the evolutionist theme concerns not so much the constitution of a continuous table of species, as the description of discontinuous groups and the analysis of the modes of interaction between an organism whose elements are interdependent and an environment that provides its real conditions of life”. |

| 34. | then at the page 171 he uses again the term “evolutionism” without to put it between single quotation marks; see also here, p. 71: “a theme, in the eighteenth century, of an evolution of the species deploying in time the continuity of nature, and explaining the present gaps in the taxonomic table”; on the different meanings of the different forms of evolutionism, see also pp. 116–17, 159–60. |

| 35. | “The problem is to know how this configuration of classical taxonomy will be transformed. How one will be able to find, in individuals who from then on will be known across species and genus, the same single thread of reality (for Darwin, this thread will be genealogy.) How Darwin will, on the one hand, eradicate the epistemological threshold and show that, in fact, we have to begin by knowing the individual with its individual variations; on the other, he will show how, beginning with the individual, what will be established as its species, its order, or its class will be the reality of its genealogy: a succession of individuals. We have, then, a uniform table, without a system, with a double threshold”. |

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).