Abstract

All work sectors have been affected by the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. The perception of risk combined with the lack of safety and fear for their own safety have caused severe psychological discomfort in workers. Of all the work sectors, the most affected was certainly the healthcare sector. In hospitals, medical staff were at the forefront of the battle against COVID-19, providing care in close physical proximity to patients and had a direct risk of being exposed to the virus. The main objective of the study was to investigate the perception of a psychosocial safety climate and the effect on engagement and psychological stress in a sample of 606 healthcare workers (physicians 39.6%, nurses 41.3%, healthcare assistant 19.1%), belonging to six organisations and organised into 11 working groups. Furthermore, we wanted to investigate the mediating effect of workaholism at both individual and group level. The results partially confirmed our hypotheses and the mediating effect at the individual level of working compulsively. A psychosocial safety climate in healthcare workers led to a decrease in engagement through the mediation of working compulsively. The mediating effect of working compulsively might be due to a climate that did not guarantee or preserve the psychological health and safety of healthcare workers. In this research, the most important limit concerns the number of organisations and the number of groups.

1. Introduction

The rapid spread of the coronavirus disease in 2019 (COVID-19) had a huge impact on the health of the global community. This pandemic has caused serious psychological health problems in the general population [1] and the healthcare workforce has been the most demanding and committed of institutions [2]. In hospitals, medical staff were at the forefront of the battle against COVID-19, providing care in close physical proximity to patients and had a direct risk of being exposed to the virus [3]. These workers faced an unprecedented dramatic public health situation, which caused sudden changes in their personal and professional lives.

During emergencies, such as pandemics, exceptional precautionary actions are adopted with different effects on the population and target workers involved. The general proposals for the population are to stop or slow down daily activities, social distance, reduce interactions between people, and use masks and good ventilation to reduce the possibility of new infections [4,5,6]. On the other hand, for healthcare workers, work demands and workloads have increased along with the deterioration of physical and psychological well-being, and the fear of becoming infected and transmitting the virus to family and friends [7,8]. These critical conditions are increased by the requirement to wear personal protective equipment which, although essential, caused and still causes discomfort and some difficulty in breathing.

Epidemic studies proved that previous infectious diseases caused long-term and persistent psychopathological consequences in this category [9,10]. For example, previous evidence from the 2002–2004 Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) epidemic and the 2015 Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) outbreak, showed that frontline healthcare professionals reported a lack of support in the workplace and higher levels of acute psychological distress, anxiety, depression, and increased long-term risk of developing Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) [2,11,12,13,14,15]. SARS and MERS outbreak experiences have crucially compromised healthcare professionals’ well-being, as it also did during the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, it is also relevant to note the effects on professional performance and the quality of the care service provided. Due to the pressure conditions to which they are exposed, healthcare professionals are more at risk of burnout, with direct and indirect consequences [16,17,18]. Alharbi and colleagues [19] describe, for example, the increased risk for this group of suffering from compassion fatigue, i.e., the “cost of caring”, understood as a gradual decrease in the desire to care; it manifests in reduced work performance, fatigue (emotional and physical), high stress, and lowered moral status. It results mainly from repeated contact with patients and frustration that can arise from not alleviating their pain; situations that are very common in this pandemic and in similar circumstances. Furthermore, due to the severity of the outbreak, the absence of treatment and the scarcity of means, have forced professionals to make difficult and frustrating decisions, with the consequent outcomes of moral distress [20].

Frontline healthcare workers experienced an unexpected increase in workload in a context of uncertainty, helplessness, alienation, and isolation, making them more vulnerable to infection [7,21,22]. Compared to other healthcare workers or other categories of workers, they tend to report a higher prevalence of adverse psychological outcomes such as psychological distress [9,23,24,25,26]. Additionally, excessive workload may intensify work pace and the pressure to meet all of the work demands of healthcare workers, which, in turn, would increase the tendency to work excessively and compulsively (i.e., workaholism) [27,28]. The term workaholism has been used to refer to those workers who have developed an excessive need for work that interferes with their health, happiness, relationships with others, and social functioning [29]. To mitigate such adverse psychological outcomes, perceived safety, trust in the organisation, and personal and collective efficacy [30] may play a critical role as protective factors against the above-mentioned outcomes. Perceived safety is the degree to which an individual can effectively manage physical, psychological, and cultural threats from the environment [31]. Several studies showed that a lack of perceived safety leads to lower levels of personal well-being [32,33,34], lower engagement [35,36], higher levels of anxiety [37], and a higher tendency to become a workaholic [38]. Engagement has been defined as a positive motivational state that promotes a strong commitment of the individual to work and, in turn, fosters positive results for workers and companies [39,40,41]. Furthermore, discrepancies in safety perceptions between nurses and physicians have been shown to influence different levels of psychosocial well-being during communicable disease outbreaks [42,43,44].

In response to this health crisis, the psychological care of healthcare professionals should be an essential part of the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic because of their vulnerability [45]. Several protective factors can help healthcare workers to cope with the emergency, during outbreaks, or in other critical situations. The aim of these protective factors was to procure essential resources, promote a psychosocial safety climate (PSC), and mitigate the negative effects of the job [38,46,47,48]. PSC is defined as shared employees’ perceptions of the “policies, practices, and procedures for the protection of worker psychological health and safety” (p. 580) [49]. Among these protective factors are: the practice of physical exercise [50], clarity in communication, availability of personal protective equipment, need for adequate rest, and practical and psychological support [51]. Ripp and colleagues [48] specifically reported some key actions to promote and maintain a good state of emotional well-being during a pandemic. They emphasised the importance of good teamwork, involving all human resources and the leader. Priority areas to be focused on include: (a) meeting basic daily needs; (b) improving communications in order to spread reliable and timely information; and (c) developing psychosocial and mental health resources.

Although research has identified a psychosocial safety climate as a protective factor that could promote work engagement and reduce psychological distress [49,52], scholars have not investigated whether compulsive and excessive work (i.e., workaholism) could mediate these relationships and compromise the positive effect of a psychosocial safety climate. Therefore, in this study, we aim to determine whether the effects of a psychosocial safety climate on work engagement and psychological distress are mediated by working excessively and working compulsively. Furthermore, we intend to assess the high levels of psychological distress perceived by healthcare workers during the pandemic.

3. The Connections and Effects of the PSC on Work Engagement

In organisational psychology literature, work engagement is defined as a cognitive-affective state characterised by vigour, dedication, and absorption [62]. It is an important work-related psychological outcome that can be correlated with perceived PSC in the workplace. This link is strongly influenced by the construct’s effect on employee well-being, job performance levels, and intentions to stay at work; in short, it is the desired and expected outcome for promoting and maintaining a high level of employees’ quality of life [58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67].

The connections and effects of PSC on work engagement can be explained by Social Exchange Theory (SET) [68]. According to this theory, this connection is based on the norm of reciprocity; the more senior management shows care and concern for the physical and psychological health of their employees, the more motivated they will feel to invest and engage in their work, even under high job demands [69]. Recent studies have reported that PSC affects and predicts work engagement, thus reducing exposure to psychosocial risks, such as bullying and harassment [52]. Several studies confirm the relationship between certain psychological conditions, such as the perception of safety and the commitment of employees [35]. When workers perceive psychological safety in their working context, they exhibit greater engagement, which, in turn, is reflected in attitudes and behaviour free of concern for negative consequences on their image, career, or status.

In the healthcare sector, work engagement is a strong and helpful personal resource because it could help frontline professionals cope with stressful situations they have experienced. Work engagement also has an important impact on the quality of care provided [70] and is considered a protective factor against burnout and post-traumatic stress including its sub-factors [71,72]. Moreover, a good level of work engagement seems to negatively predict absenteeism and negative work outcomes. Some recent studies have investigated the relationship between psychosocial safety climate and work engagement, highlighting its value and relevance in stressful procedures such as hospital accreditation. In such procedures, it is important that healthcare workers connect to organisational values and objectives through increased work engagement, to achieve greater success and the sustainability of their organisation (i.e., hospital). These studies found that the presence of adequate levels of PSC, prior to hospital accreditation and as perceived by individual healthcare workers, offered a safety net in terms of available options that could help healthcare workers cope with challenging work situations and prevent the experience of burnout. Therefore, it is certain that even high scores in individual PSC perceptions prior to hospital accreditation could buffer the effects of job demands on the health and psychological well-being of healthcare workers and strengthen the relationship between job resources and positive motivational behaviour [73,74]. In view of the considerations above, it was hypothesised that:

H1:

Psychosocial Safety Climate is an antecedent of work engagement.

4. Safety Outcomes: Psychological Distress

The relevance of safety to people and organisations has stimulated investigation of the practical consequences of a psychosocial safety climate, with a strong emphasis on safety performance and safety outcome indicators. At the individual level, researchers have mainly focused on the relationship between safety behaviour and critical hazards, and more recently, aspects of individual health and well-being have been integrated into the research [75,76]. Previous studies have shown that a positive psychosocial safety climate is more likely to be positively associated with higher levels of safety compliance and participation behaviours, which, in turn, are associated with a reduction in negative safety outcomes such as injuries and accidents [75,77,78,79,80]. The motivation behind this hypothesis is that employees’ perceptions of a psychosocial safety climate directly affect their behaviour, which, in turn, influences the occurrence of accidents and injuries.

Employee health and well-being is another individual outcome that can be linked to a psychosocial safety climate. Specifically, it has been reported that there is a strong relationship between a psychosocial safety climate and the preservation of positive health and well-being [81,82]. Consistent with an occupational stress process, it is anticipated that negative perceptions of a psychosocial safety climate are expected to lead to stressful experiences and reduced psychological well-being. Therefore, a negative psychosocial safety climate may increase the vulnerability to accidents and injuries via reduced physical and psychological well-being [83,84]. Cognitive processes, such as distraction, inattention, and fatigue, are potential explanatory mechanisms for this process [85].

Studies have shown that a psychosocial safety climate allows the establishment of a working environment that is perceived as safe by workers and, by reducing the risks associated with the workload, manages to alleviate psychological stress. Consequently, a psychosocial safety climate may be crucial to ease the perceived stress of healthcare workers and promote their psychological health, whereas, in particularly precarious and unsafe conditions, such as during a pandemic, this perception of safety may be undermined, causing higher levels of stress [49,54,86,87].

Several meta-analyses provided evidence and raised awareness that a high proportion of healthcare professionals experienced significant levels of psychological distress, anxiety, depression, and insomnia during the COVID-19 pandemic, and were more vulnerable to occupational hazards. Healthcare workers have worked under conditions of high pressure and uncertainty from the beginning of the pandemic and have faced the pandemic’s challenges by increasing their workload and working at high intensity [88]. They are experiencing various negative impacts on their physical and mental health, leading to physical and psychological exhaustion [89]. The increasing and continuous presence of confirmed cases of COVID-19, mandatory use of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) in high-temperature environments, along with a lack of adequate rest time are all factors that contribute to stressful and burdensome situations. Previous studies that examined other infectious diseases confirmed that healthcare workers can experience not only severe emotional stress during the outbreak [13,90], but also burnout, traumatic stress, and other mental health symptoms even after the outbreak [91]. The emotional exhaustion of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic is particularly serious.

Two important consequences related to this psychological stress are peritraumatic distress and stigma and fear toward these workers. Peritraumatic distress is emotional and physiological distress experienced during and/or immediately after a traumatic event. This stress is an antecedent of post-traumatic stress disorder, and it is related to several mental diseases. These healthcare workers are more vulnerable to this specific stress. In addition, psychological stress may increase when people around health workers avoid them due to stigma or fear [92]. Stigma also has a negative impact on mental health, and stigmatized healthcare workers have been reported to experience greater stress. All these factors, even with sustained increases in the number of confirmed patients, can increase the vulnerability of healthcare workers, but can also lead to poorer mental health and quality of life. These effects are dangerous because they may also affect the quality of patient care. Given the unpredictable nature of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is necessary to identify the factors involved in the psychological distress of healthcare workers to mitigate the effects of a long period of COVID-19 spread, not only in the population but also for these workers.

For these reasons, the hypotheses for our study are:

H2:

Healthcare workers experienced a high level of psychological distress.

H3:

PSC is an antecedent of psychological distress.

5. How PSC Relates to Workaholism

According to Ng, Sorensen, and Feldman [93], workaholism can be identified as an addiction to work that involves obsession, and the use of personal time and large time frames devoted to work. As a result, it can cause loss of self-esteem, compulsive behaviour towards work, and a constant commitment to work regardless of negative outcomes.

Studies have shown that job demands (e.g., work pressure, cognitive and emotional demands) and job resources (e.g., development opportunities and job security) have been recognised as antecedents of workaholism [94,95]. Andreassen and colleagues [96] have observed in Norwegian nurses that job demands may represent a stressor that leads the worker to increase his/her pace of work hoping to escape the workload as soon as possible. As Schaufeli, Taris, and van Rhenen [97] have stressed, workers can be more tempted to put effort and energy to fulfil particularly important job demands, leading them to work constantly. Furthermore, the most important job requests can foster performance anxiety, leading employees to spend a lot of time mulling over work and working compulsively [98]. One solution to manage workaholism may be to change the expectations of companies regarding workload [96]. Regarding job resources, structural resources could also positively influence workaholism in workers. As Balducci and colleagues [96] and Yulita Idris and Dollard [38] suggest, organisations should provide social resources to manage or even reduce the effect of job demands and job resources on workaholism.

It is interesting to note how Gillet and colleagues [94] have highlighted that a psychosocial safety climate can alleviate the negative effects of pressure and long work sessions due to job demands and adverse behaviour fostered by misuse of emotional and cognitive resources, reducing the risk of displaying workaholic behaviours. As Schaufeli and colleagues [62,99] claim, companies that create a psychosocial safety climate may be able to implement better workload management procedures and avoid over-absorption of workers in their work. In addition, it has been reported that the above-mentioned climate may reduce the risk of accidents and injuries in the workplace [99,100]. Therefore, a psychosocial safety climate could be an important asset to help reduce the risk of workaholism.

The relationship between psychosocial safety climate and workaholism can be justified by the job demands–resources model, as it shows how job demands can drain the worker’s energy and have a severe impact on his or her psychological health. In a study conducted in 26 police departments in Malaysia, it has been observed that in departments with high levels of psychosocial safety climate, there is a higher chance that job resources are used in a healthy way. Consequently, the risk that workers would start to use these resources in a compulsive and uncontrolled manner, leading to workaholism, is significantly reduced [38].

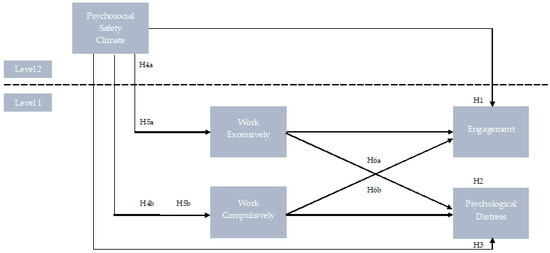

Considering these initial findings presented by the literature on the effect of PSC on workaholism, it has been hypothesized that (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

The hypothesised model. H4_a: Psychosocial safety climate negatively affects working excessively. H4_b: Psychosocial safety climate negatively affects working compulsively. H5_a: Psychosocial safety climate is an antecedent of the levels of working excessively. H5_b: Psychosocial safety climate is an antecedent of the levels of working compulsively. H6_a: The effect of psychosocial safety climate on engagement and psychological distress will be mediated by working excessively.H6_b: The effect of psychosocial safety climate on engagement and psychological distress will be mediated by working compulsively.

6. Method

6.1. Participants and Procedure

The study involved 606 healthcare workers (physicians 39.6%, nurses 41.3%, healthcare assistants 19.1%) at the forefront of the battle against COVID-19 during the pandemic (males were 38.9% of the total sample), belonging to six organisations and organised into 11 working groups. Each group consisted of members from a distinct division of the organisation who were assigned to the same head of department. Participants came from different areas of Italy (North, 32%; Central, 17%; South, 51%). Their age ranged between 23 and 63 (Mage = 36.3, SD = 11.9). With reference to educational level, 81.7% had completed a minimum of 17 years of school. Respondents had an average seniority of 9.5 (SD = 1.1).

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was authorized by the Internal Ethics Review Board of the Department of Educational Sciences (Section of Psychology) of the University of Catania (Ierb-Edunict-2020/4); data were collected between May 2020 and October 2021 and the related research procedures followed all indications provided by the guidelines of the AIP (Italian Association of Psychology) and its Ethical Council.

Participation was voluntary. Participants were recruited through convenience sampling, and companies were contacted via written correspondence; once the approval from the HR department was given, a link to the survey was published in the companies’ social media groups (i.e., LinkedIn, Twitter) and they were also approached in workgroups via written correspondence (e.g., email or invitation by letter to participate). Participants received a survey package including the questionnaire, a cover letter explaining the study’s purposes, and a consent form stressing that participation was anonymous and voluntary. By clicking on the link, respondents were presented with a participant information sheet and an informed consent form, which, only once accepted, led to the survey with instructions on how to complete it. Questionnaires required approximately 20 min to be completed.

6.2. Measures

6.2.1. Psychosocial Safety Climate (PSC-12)

Twelve items from Hall et al and colleagues [53] were used to assess the construct of psychosocial safety climate (PSC-12). Four subscales comprising the scale: (1) management commitment; (2) management priority; (3) organisational communication; and (4) organisational participation. All items were rated on a five-point Likert scale (from 1 = ‘Strongly disagree’ to 5 = ‘Strongly agree’). Literature studies reported that the aggregate PSC score is significantly related to emotional exhaustion, psychological distress, depression, and engagement.

6.2.2. Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES-9)

The scale was developed by Schaufeli and Bakker [101]; it is used for the evaluation of work involvement, meant as a positive and fulfilling state of mind related to a personal work situation. The Italian version of the scale is made by Balducci and colleagues [102]. The UWES-9 contains three items for each of the three factors of vigour, absorption, and dedication. For each statement, responses were given using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 0 = never to 6 = always.

6.2.3. Dutch Work Addiction Scale (DUWAS)

The DUWAS [103], Italian adaptation by Nonnis and colleagues [104] and Balducci and colleagues [105], is a self-report questionnaire consisting of 10 items, scored on a 4-point Likert-type scale (from 1 = never or almost never to 4 = almost always or always). It was developed to investigate the concept of workaholism, and measures two sub-factors: Working Excessively (WE) and Working Compulsively (WC).

6.2.4. Kessler 10 Psychological Distress Scale (K10)

To measure the psychological impact of the COVID-19 outbreak, the Kessler 10 Psychological Distress Scale (K10) was used [106]. Ten items were used to assess anxiety and depressive symptoms experienced during the most recent 4-week period. Items are rated using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Low scores indicate low levels of psychological distress, while high scores indicate high levels of psychological distress. Consistent with previous validation studies [107,108], we adopted the cut-off score > 19. The psychometric reliability of the K10 makes it attractive for use in general health surveys [106].

6.3. Data Analysis

First, Confirmatory Factor Analyses (CFA) of the five scales (Psychosocial Safety Climate, Work Compulsively, Work Excessively, Engagement, and Psychological Distress) were carried out to gain evidence of the discriminant validity of these measures. A five-factor model with all the items were loaded onto seven separate factors using individual-level data.

Thereafter, three alternative CFA models were conducted, and the fit of these models was compared with the five-factor model (see Table 1). The models’ goodness-of-fit was detected through the Tucker Lewis Index (TLI), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). RMSEA values close to 0.06 are indicative of a good fit, values between 0.07 and 0.08 are considered a moderate fit, and values between 0.08 and 0.10 are indicative of a marginal fit. The indices CFI and TLI, higher values show better fit. CFI and TLI values above 0.95 show a very good fit, values between 0.90 and 0.95 are indicative of a marginally acceptable fit, and values lower than 0.90 indicate a poor fit [65]. Furthermore, χ2 values and Δχ2 values between the competing models are presented, but they are sensitive to sample size [109], so Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) were also presented (lower values indicate a better fit). ΔCFI was also used with values not exceeding 0.01 indicating that the models are equivalent in terms of fit. Furthermore, we used other statistical techniques such as bivariate correlation, which were implemented by using SPSS 26.0. Homogeneity of climate perceptions was assessed with rwg [110,111], intraclass correlation [ICC (1) Anova Random Effect 1-way], and reliability of the mean [ICC (2) 2-way Anova Fixed effect], [112,113]. The reliabilities were assessed through McDonald’s omega (ω), Cronbach’s alpha (α), and Composite Reliability (CR). Both ω and α should be above 0.70, while the CR should be above 0.50 [114].

Next, we ran a multilevel structural equation model to assess our proposed mediation model and the pathways between our variables. Monte Carlo (MC) confidence intervals were used for testing the significance of the indirect effects, as it is argued to be a more viable and robust method for calculating confidence intervals for complex and simple indirect effects when working with a multilevel model (To test our proposed model, we ran a Multilevel Structural Equation Model (MSEM). Psychosocial Safety Climate was analyzed on the team level and Work Compulsively, Work Excessively, Engagement, and Psychological Distress were analyzed on the individual level.

7. Results

7.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Table 1 shows the results of the CFA with the goodness-of-fit indices with all five variables included in the study onto five separate factors and three alternative models. The differences between the 5-factor model (Model 1) and the alternative model 2 (ΔRMSEA = 0.077, ΔCFI = 0.278, ΔTLI = 0.028), alternative model 3 (ΔRMSEA = 0.017, ΔCFI = 0.040, ΔTLI = 0.037), indicates that the study model fit the data better.

However, the differences between the 5-factor model (Model 1) and alternative model 4 were minimal (ΔRMSEA = 0.004 0, ΔCFI = 0.016, ΔTLI = 0.011). Therefore, we examined the difference in Chi-square statistics of the 5- factor model and alternative model 4 and found that the difference between the Chi-square statistics was statistically significant (Δχ2 = 49.81, Δdf = 8, p < 0.001). Given that the 5-factor model has a smaller Chi-square value, it is considered to have a better fit for the data. Thus, the evidence above supports the discriminant validity of the five scales.

Table 1.

Confirmatory factor analysis results for the study model and alternative models for comparison.

Table 1.

Confirmatory factor analysis results for the study model and alternative models for comparison.

| Model | χ2 (df) | p | RMSEA | CFI | TLI | SRMR | AIC | BIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 5-factor model: the five study variables loaded onto five separate factors | 186.713 (64) | 0.000 | 0.058 | 0.921 | 0.942 | 0.039 | 138.105 | 198.228 |

| Model 2 The five study variables loaded onto a single factor | 2224.59 (78) | 0.000 | 0.135 | 0.643 | 0.662 | 0.161 | 573.182 | 710.274 |

| Model 3 Four factor model with Work Compulsively and Work Excessively loading onto single factor | 368.879 (69) | 0.000 | 0.075 | 0.884 | 0.894 | 0.067 | 462.141 | 560.124 |

| Model 4 Four Factor model with Psychological Distress and Engagement loading onto single factor | 236.521 (72) | 0.000 | 0.062 | 0.905 | 0.931 | 0.044 | 364.274 | 401.589 |

7.3. Descriptive Statistics, Reliability, and Correlations among Study Variables

Table 2 shows a descriptive statistics and correlation matrix for the study variables, both at the within and between levels. At the individual level, Psychosocial Safety Climate correlates with all variables except Work Excessively; there is a high correlation between Work Compulsively (r = −0.35, p < 0.001, H3) and Engagement (r = −0.33, p < 0.001). Moreover, at group level there is a significant correlation between PSC and WoC (rs = −0.85, p < 0.001) and Engagement (rs = −0.68, p < 0.05), and PSD (rs = −0.76, p < 0.05) (Table 2). However, it should be highlighted that the correlation between PSC and PSD is positive at the individual level (rs= 0.14, p < 0.001) and negative at the group level (rs = −0.76, p < 0.001). It could be that a Psychosocial Safety Climate is perceived as crucial in reducing Psychological Distress at the departmental level, whereas PSC is not perceived as safe due to the risks taken by each healthcare worker, leading to an increase in their psychological distress.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics, reliability, and correlation between variables at within and between level.

The average PSD value falls within the cut-off threshold indicated by Kessler and colleagues [108] as “severe disorders” (M = 33.95, SD = 5.98), for this reason, the hypothesis H2 is confirmed. Furthermore, following the guidelines of the Italian validation of DUWAS [100], in our sample, 18.6% exceeds the cut-off threshold of Work Excessively (M = 2.95; SD = 0.46; Range = 2.60–4.00) and 24.7% of Work Compulsively (M = 3.12, SD = 0.54; Range = 2.60–3.60).

Composite reliability and average variance extracted were: CR 0.91, AVE 0.70, for PSC; CR 0.86, AVE 0.68, for WoE; CR 0.80, AVE 0.64, for WoC; CR 0.94, AVE 0.75, for Engagement; CR 0.78, AVE 0.59, for PSD. The two coefficients, Cronbach’s alpha (α) and McDonald’s omega (ω), revealed both identical values and, together with CR and AVE, they indicated overall a very good internal consistency of the scale.

7.4. Multilevel Analysis

The unstandardised coefficients of the multilevel model with Engagement, Work Excessively, and Work Compulsively as outcome variables have been estimated in Table 3. It was found that Psychosocial Safety Climate at the department level (i.e., level 2) negatively affects Engagement (γ = −0.38; SE = 0.55; p < 0.01) and Work Compulsively (γ = −0.29; SE = 0.19; p < 0.01) of healthcare workers at the individual level (i.e., level 1); whereas no significant effect was observed on Work Excessively (level 1; γ = −0.01; SE = 0.05; p = n.s.; Table 4). It means that our results supported hypotheses H1, H4_b, and H5_b while hypotheses H4_a, H5_a, and H6_a were not supported. Regarding hypotheses H3 and part of H6_b, they were not supported by our findings, as the effect of Psychosocial Safety Climate on Psychological Distress is not statistically significant (level 1; γ = −0.14; SE = 0.55; p = n.s.; Table 4).

Table 3.

Unstandardised coefficients of the multilevel model.

Table 4.

Unstandardised coefficients of the multilevel model.

Subsequently, the multilevel mediation hypothesis (H6_b) has been tested. As Zhang et al. [115] suggest, three steps have been taken to test the 2-1-1 multilevel mediation [i.e., X (Level 2)→M (Level 1)→Y (Level 1)]. Firstly, a significant negative effect of Psychosocial Safety Climate on Engagement is estimated (X→Y). Secondly, the Psychosocial Safety Climate showed a significant negative effect on Work Compulsively (X→M). Finally, Work Compulsively had negatively affected Engagement (M→Y; Table 5). A 95% confidence interval (C.I.) was used to test mediation pathways and it was identified that Work Compulsively fully mediated the relationship between the Psychosocial Safety Climate and Engagement (indirect effect: −0.421, C.I. −0.831, −0.010; Table 6). Therefore, the results partially supported our hypothesis (H6_b).

Table 5.

Unstandardised coefficients of the multilevel model.

Table 6.

Multilevel mediation 2-1-1.

8. Discussion

As our purpose was to investigate how healthcare workers were affected by the perceived lack of psychological safety during the COVID-19 pandemic, our study revealed how psychosocial safety climate at the departmental level could have a major influence on workers in the healthcare sector. Specifically, the study has shown that psychosocial safety climate positively affects work engagement (H1), and negatively working compulsively (H4_b; H5_b). Psychosocial safety climate has often been seen as an organisational dimension that can help workers reduce job demands and job resources, improve the management and allocation of demands, and achieve their work objectives. The research stressed how organisations with high levels of psychosocial safety climate succeed in creating the appropriate working conditions by providing support and procedural justice, leading to increased engagement [54,116,117]. However, it implies that a company is able to ensure such a climate by managing the workload and resources available to the employee. Additionally, healthcare workers have been found to experience high levels of psychological stress during the COVID-19 pandemic (H2) as also reported by De Sio and colleagues [83].

The finding that a psychosocial safety climate in healthcare workers leads to a decrease in engagement through the mediation of working compulsively (H6_b) perfectly reflects the state of crisis and hysteria caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. As Spector and colleagues [118] suggested, inadequate job resources (e.g., psychosocial safety climate) could lead to counterproductive and negative behaviours and reactions. As the COVID-19 pandemic brought tremendous pressure to healthcare institutions, hospitals, and their workers, work demands have increased and the number of available resources has shrunk. This led healthcare institutions to create a poor psychosocial safety climate in which workload could not be managed, forcing workers to take on more work and to become significantly disengaged. Similarly, a lack of psychosocial safety climate might induce workers to hide their emotions, to feel unheard by their organisation, or to feel that their need for well-being is overlooked [49].

The mediating effect of working compulsively in the above relationship between psychosocial safety climate and engagement might be due to a climate that did not guarantee or preserve the psychological health and safety of healthcare workers. This led them to feel obliged to work intensively and to blame themselves if they took time off or had breaks, reducing their engagement in their job over time. As Yulita and colleagues [38] claimed, workaholism could be considered the “darkside” of engagement as the former involved a negative and intense investment of forces, while the latter (i.e., engagement) was more energetic and positive. Compulsive work due to a state of emergency may cause tension, anger, and irritation, leading to a reduction in all positive engagement-related behaviours such as happiness and enthusiasm [119].

Theoretically, the results show the importance of the role that working compulsively plays as a mediator, as it can undermine the psychosocial safety climate causing workers to become detached from their work. In these frenetic times of insufficient readiness for a global pandemic, we need to understand whether healthcare organisations are prepared to support workers in their time of need, or whether all the burden is placed solely on these workers. For this reason, these results offer an insight into the role of working compulsively during the COVID-19 pandemic and the need to improve the perceived psychosocial safety at the departmental level in such a way that it positively influences healthcare workers’ engagement at the individual level.

Given these findings, it is surprising that there is no significant effect of the psychosocial safety climate on psychological distress despite the presence of a positive correlation between the two constructs at the individual level and a negative one at the department level. This could be linked to different levels of pressure and workload among the various health departments investigated but accompanied by a psychosocial safety climate that is incapable of promoting psychological health and safety. Our research unlocks the possibility of investigating the negative effects of a poor psychosocial safety climate and compulsive work on effective employee engagement in various work environments, not only in the healthcare sector.

It should be acknowledged that such research is not without limitations. Firstly, a cross-sectional research design has been adopted which would imply that the causal direction of one variable in relation to another could not be considered, leading to the assessment of just the relationships between the variables [120]. On the other hand, the literature has strongly supported the job demands–resources model as well as the social exchange theory to justify the role of the psychosocial safety climate as an antecedent and the respective effects on workaholism (i.e., working excessively) and, in turn, on engagement in our model. The following study sets the basis for a longitudinal research design to investigate how the effect of these dimensions on healthcare workers changes as pressures on the healthcare system are relieved and the pandemic state is gradually lifted. Secondly, data collection has been carried out using self-report questionnaires administered at a single point in time, so there may be the risk of common method bias (i.e., variance that could be allocated to the measurement method instead of the actual construct being investigated). The reliability and validity of self-report questionnaires has been widely recognised and several studies have successfully employed them, e.g., [38] but future research should undertake two separate time-lagged questionnaires for antecedents and outcomes variables to reduce the risk of common method bias.

Finally, perhaps the most important limit concerns the number of organisations (N = 6) and the number of groups (11); in the literature, this number should be higher, but the situation related to the pandemic and the type of sample (healthcare workers who have operated on the front line during the COVID-19 pandemic) did not allow us to collect data from more organisations and groups. According to Maas and Hox [121], research usually suggests giving more relevance to the group-level sample size, but a larger individual-level sample size may partially compensate for a small number of groups. As our sample was greater than 30, the group size may be considered acceptable [121,122]. Furthermore, we conducted several reliability analyses which supported the results of our model (homogeneity, reliability, etc.).

Despite these limitations, it is important to recognise the relevance of this study in understanding the impact that the psychosocial safety climate had on healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. More specifically, there is a need to further investigate the psychosocial safety climate in the health sector to understand how policies, procedures, and practices can be improved to preserve the psychological health and safety of employees. The improvement of the above-mentioned climate becomes vital to provide employees with a physically and psychologically safe working environment. This can hopefully reduce their compulsive work tendency so that workers’ engagement in work is positive and healthy.

9. Conclusions

In conclusion, our study has shown how a psychosocial safety climate (L2) at the department level could affect, at the individual level, healthcare workers’ work engagement (L1) through the mediation effect of working compulsively (L1). Specifically, this perception of safety within the health context has been compromised during the pandemic due to the need for healthcare workers to work at a compulsive pace which, in turn, has reduced their level of engagement. Furthermore, this category of workers has experienced high levels of psychological distress which has been identified as a severe disorder. Considering this, we would have expected the psychosocial safety climate to affect psychological stress, but the absence of this effect could be related to different workloads between the various departments, which, in turn, led to unequal levels of perceived stress. Further studies should investigate the implications of a psychosocial safety climate and workaholism on workers in different sectors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.P. and V.E.S.; methodology, S.P.; software, S.P. and V.E.S.; validation, M.M., V.E.S. and A.C.; formal analysis, S.P.; investigation, M.M.; resources, A.C.; data curation, S.P. and V.E.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M.; writing—review and editing, S.P.; visualization, V.E.S.; supervision, S.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by CISLa project Starting Grant 2020 University of Catania.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was authorized by the Internal Ethics Review Board of the Department of Educational Sciences (Section of Psychology) of the University of Catania (Ierb-Edunict-2020/4); data were collected between May 2020 and October 2021 and the related research procedures followed all the indications provided by the guidelines of the AIP (Italian Association of Psychology) and its Ethical Council.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wang, C.; Horby, P.W.; Hayden, F.G.; Gao, G.F. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet 2020, 395, 470–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giusti, E.M.; Pedroli, E.; D’Aniello, G.E.; Stramba Badiale, C.; Pietrabissa, G.; Manna, C.; Stramba Badiale, M.; Riva, G.; Castelnuovo, G.; Molinari, E. The Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Outbreak on Health Professionals: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sim, M.R. The COVID-19 pandemic: Major risks to healthcare and other workers on the front line. Occup. Environ. Med. 2020, 77, 281–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, W.; Hao, F.; McIntyre, R.S.; Jiang, L.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, X.; Zou, Y.; Hu, Y.; Luo, X.; et al. Is returning to work during the COVID-19 pandemic stressful? A study on immediate mental health status and psychoneuroimmunity prevention measures of Chinese workforce. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 87, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Pan, R.; Wan, X.; Tan, Y.; Xu, L.; McIntyre, R.S.; Choo, F.N.; Tran, B.; Ho, R.; Sharma, V.K.; et al. A longitudinal study on the mental health of general population during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 87, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilder-Smith, A.; Freedman, D.O. Isolation, quarantine, social distancing and community containment: Pivotal role for old-style public health measures in the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak. J. Travel Med. 2020, 27, taaa020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Luo, D.; Haase, J.E.; Guo, Q.; Wang, X.Q.; Liu, S.; Xia, L.; Liu, Z.; Yang, J.; Yang, B.X. The experiences of health-care providers during the COVID-19 crisis in China: A qualitative study. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, e790–e798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, K.; Norful, A.A.; Travers, J.; Aliyu, S. Nursing perspectives on care delivery during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 2, 100006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, C.W.; Pang, E.P.; Lam, L.C.; Chiu, H.F. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in Hong Kong in 2003: Stress and psychological impact among frontline healthcare workers. Psychol. Med. 2004, 34, 1197–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.M.; Wong, J.G.; McAlonan, G.M.; Cheung, V.; Cheung, C.; Sham, P.C.; Chu, C.M.; Wong, P.C.; Tsang, K.W.; Chua, S.E. Stress and psychological distress among SARS survivors 1 year after the outbreak. Canadian journal of psychiatry. Can. J. Psychiatry 2007, 52, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koh, D.; Lim, M.K.; Chia, S.E.; Ko, S.M.; Qian, F.; Ng, V.; Tan, B.H.; Wong, K.S.; Chew, W.M.; Tang, H.K.; et al. Risk perception and impact of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) on work and personal lives of healthcare workers in Singapore: What can we learn? Med. Care 2005, 43, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, T.; Lien, T.; Yang, C.; Ling, Y. Prevalence of psychiatric morbidity and psychological adaptation of the nurses in a structured SARS caring unit during outbreak: A prospective and periodic assessment study in Taiwan. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2007, 41, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.M.; Kang, W.S.; Cho, A.R.; Kim, T.; Park, J.K. Psychological impact of the 2015 MERS outbreak on hospital workers and quarantined hemodialysis patients. Compr. Psychiatry 2018, 87, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Sahoo, S. Pandemic and mental health of the frontline healthcare workers: A review and implications in the Indian context amidst COVID-19. Gen. Psychiatry 2020, 33, e100284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moitra, M.; Rahman, M.; Collins, P.Y.; Gohar, F.; Weaver, M.; Kinuthia, J.; Kumar, M.; Rössler, W.; Petersen, S.; Unutzer, J.; et al. Mental health consequences for healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A scoping review to draw lessons for LMICs. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 602614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barello, S.; Palamenghi, L.; Graffigna, G. Burnout and somatic symptoms among frontline healthcare professionals at the peak of the Italian COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 290, 113129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Platania, S.; Castellano, S.; Petralia, M.C.; Santisi, G. The mediating effect of the impact of quality of life on the relationship between job satisfaction and perceived stress of professional caregivers. Psicol. Salut. 2019, 1, 64–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platania, S.; Di Nuovo, S.; Caruso, A.; Digrandi, F.; Caponnetto, P. Stress among university students: The psychometric properties of the Italian version of the SBI-U 9 scale for Academic Burnout in university students. Health Psych. Res. 2020, 8, 9209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, J.; Jackson, D.; Usher, K. The potential for COVID-19 to contribute to compassion fatigue in critical care nurses. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 2762–2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, M.; Murray, E.; Christian, M.D. Mental health care for medical staff and affiliated healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. Heart J. Acute Cardiovasc. Care 2020, 9, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, L.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Wu, W.; Zhang, L.; Tan, X. Risk Factors of Healthcare Workers With Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Retrospective Cohort Study in a Designated Hospital of Wuhan in China. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 2218–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Yang, L.; Liu, S.; Ma, S.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Z.; Du, H.; Li, R.; Kang, L.; Su, M.; et al. Survey of insomnia and related social psychological factors among medical staff involved in the 2019 novel coronavirus disease outbreak. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, J.; Ma, S.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Z.; Hu, J.; Wei, N.; Wu, J.; Du, H.; Chen, T.; Li, R.; et al. Factors Associated With Mental Health Outcomes Among Health Care Workers Exposed to Coronavirus Disease 2019. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e203976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Mao, M.; Wang, S.; Yin, R.; Yan, H.O.; Jin, Y.; Cheng, Y. Posttraumatic growth in Chinese nurses and general public during the COVID-19 outbreak. Psychol. Health Med. 2021, 27, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maunder, R.G.; Lancee, W.J.; Rourke, S.; Hunter, J.J.; Goldbloom, D.; Balderson, K.; Fones, C.S.L.; Petryshen, P.; Steinberg, R.; Wasylenki, D.; et al. Factors associated with the psychological impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome on nurses and other hospital workers in Toronto. Psychosom. Med. 2004, 66, 938–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nissan, D.; Weiss, G.; Siman-Tov, M.; Spitz, A.; Bodas, M.; Shenhar, G.; Adini, B. Differences in levels of psychological distress, perceived safety, trust, and efficacy amongst hospital personnel during the COVID-19 pandemic. Res. Nurs. Health 2021, 44, 776–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillet, N.; Morin, A.J.S.; Cougot, B.; Gagné, M. Workaholism profiles: Associations with determinants, correlates, and outcomes. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2017, 90, 559–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huyghebaert, T.; Fouquereau, E.; Lahiani, F.-J.; Beltou, N.; Gimenes, G.; Gillet, N. Examining the longitudinal effects of workload on ill-being through each dimension of workaholism. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2018, 25, 144–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oates, W. Confessions of a Workaholic: The Facts about Work Addiction; World Publishing Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Lasalvia, A.; Amaddeo, F.; Porru, S.; Carta, A.; Tardivo, S.; Bovo, C.; Ruggeri, M.; Bonetto, C. Levels of burn-out among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic and their associated factors: A cross-sectional study in a tertiary hospital of a highly burdened area of north-east Italy. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e045127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard-Kang, J.L. Using culturally appropriate, trauma-informed support to promote bicultural self-efficacy among resettled refugees: A conceptual model. J. Ethn. Cult. Divers. Soc. Work 2017, 29, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, S.; Johnson, C.; Beaton, R. Fire fighters’ cognitive appraisals of job concerns, threats to well-being, and social support before and after the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001. J. Loss Trauma 2004, 9, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thormar, S.; Gersons, B.; Juen, B.; Djakababa, M.N.; Karlsson, T.; Olff, M. Organizational factors and mental health in community volunteers. The role of exposure, preparation, training, tasks assigned, and support. Anxiety Stress Coping 2013, 26, 624–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Platania, S.; Paolillo, A.; Silva, S.A. The Italian Validation of OSCI: The Organizational and Safety Climate Inventory. Safety 2021, 7, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, W.A. Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 692–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, D.R.; Gilson, R.L.; Harter, L.M. The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2004, 77, 11–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulia, P.; Mantas, C.; Dimitroula, D.; Mantis, D.; Hyphantis, T. General hospital staff worries, perceived sufficiency of information and associated psychological distress during the A/H1N1 influenza pandemic. BMC Infect. Dis. 2010, 10, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yulita, Y.; Idris, M.A.; Dollard, M.F. Effect of psychosocial safety climate on psychological distress via job resources, work engagement and workaholism: A multilevel longitudinal study. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2020, 28, 691–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, Z.S. Understanding Employee Engagement: Theory, Research, and Practice; Routledge; Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Christian, M.S.; Garza, A.S.; Slaughter, J.E. Work engagement: A quantitative review and test of its relations with task and contextual performance. Pers. Psychol. 2011, 64, 89–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Salanova, M.; González-Romá, V.; Bakker, A.B. The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J. Happiness Stud. 2002, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsubaie, S.; Hani Temsah, M.; Al-Eyadhy, A.A.; Gossady, I.; Hasan, G.M.; Al-Rabiaah, A.; Somily, A.M.; Jamal, A.A.; Alhaboob, A.A.; Alsohime, F.; et al. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus epidemic impact on healthcare workers’ risk perceptions, work and personal lives. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2019, 13, 920–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dai, Z.; Locasale, J.W. Psychological impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak on healthcare workers in China. MedRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickell, L.A.; Crighton, E.J.; Tracy, C.S.; Al-Enazy, H.; Bolaji, Y.; Hanjrah, S.; Upshur, R.; Hussain, A.; Makhlouf, S.; Upshur, R.E. Psychosocial effects of SARS on hospital staff: Survey of a large tertiary care institution. CMAJ 2004, 170, 793–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marjanovic, Z.; Greenglass, E.; Coffey, S. The relevance of psychosocial variables and working conditions in predicting nurses’ coping strategies during the SARS crisis: An online questionnaire survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2007, 44, 991–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubey, S.; Biswas, P.; Ghosh, R.; Chatterjee, S.; Dubey, M.J.; Chatterjee, S.; Lahiri, D.; Lavie, C.J. Psychosocial impact of COVID-19. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2020, 14, 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loh, M.Y.; Idris, M.A.; Dollard, M.F.; Isahak, M. Psychosocial safety climate as a moderator of the moderators: Contextualizing JDR models and emotional demands effects. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2018, 91, 620–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripp, J.; Peccoralo, L.; Charney, D. Attending to the emotional well-being of the health care workforce in a New York City health system during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acad. Med. 2020, 95, 1136–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollard, M.F.; Bakker, A.B. Psychosocial safety climate as a pre- cursor to conducive work environments, psychological health problems, and employee engagement. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 83, 579–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platania, S.; Paolillo, A. Validation and measurement invariance of the Compound PsyCap Scale (CPC-12): A short universal measure of psychological capital. An. Psicol. 2022, 38, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Que, J.; Shi, L.E.; Deng, J.; Liu, J.; Zhang, L.I.; Wu, S.; Gong, Y.; Huang, W.; Yuan, K.; Yan, W.; et al. Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers: A cross-sectional study in China. Gen. Psychiatry 2020, 33, e100259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, R.; Dollard, M.F.; Tuckey, M.R.; Dormann, C. Psychosocial safety climate as a lead indicator of workplace bullying and harassment, job resources, psychological health and employee engagement. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2011, 43, 1782–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, G.B.; Dollard, M.F.; Coward, J. Psychosocial safety climate: Development of the PSC-12. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2010, 17, 353–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idris, M.A.; Dollard, M.F.; Coward, J.; Dormann, C. Psychosocial safety climate: Conceptual distinctiveness and effect on job demands and worker psychological health. Saf. Sci. 2012, 50, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohar, D. Safety climate in industrial organizations: Theoretical and applied implications. J. Appl. Psychol. 1980, 65, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadow, A.J.; Dollard, M.F.; Mclinton, S.S.; Lawrence, P.; Tuckey, M.R. Psychosocial safety climate, emotional exhaustion, and work injuries in healthcare workplaces. Stress Health 2017, 33, 558–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLinton, S.S.; Dollard, M.F.; Tuckey, M.R. New perspectives on psychosocial safety climate in healthcare: A mixed methods approach. Saf. Sci. 2018, 109, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbesleben, J.R.; Wakefield, B.J.; Wakefield, D.S.; Cooper, L.B. Nurse burnout and patient safety outcomes: Nurse safety perception versus reporting behavior. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2008, 30, 560–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, L.H.; Johnson, J.; Watt, I.; Tsipa, A.; O’Connor, D.B. Healthcare Staff Wellbeing, Burnout, and Patient Safety: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dollard, M.F.; Opie, T.; Lenthall, S.; Wakerman, J.; Knight, S.; Dunn, S.; Rickard, G.; MacLeod, M. Psychosocial safety climate as an antecedent of work characteristics and psychological strain: A multilevel model. Work Stress 2012, 26, 385–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keeffe, V.J.; Thompson, K.R.; Tuckey, M.R.; Blewett, V.L. Putting Safety in the Frame: Nurses’ Sensemaking at Work. Glob. Qual. Nurs. Res. 2015, 2, 2333393615592390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; Van Rhenen, W. How changes in job demands and resources predict burnout, work engagement and sickness absenteeism. J. Organ. Behav. 2009, 30, 893–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bakker, A.B. Building engagement in the workplace. In The Peak Performing Organization; Burke, R.J., Cooper, C.L., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2009; pp. 50–72. [Google Scholar]

- Rich, B.L.; LePine, J.A.; Crawford, E.R. Job engagement: Antecedents and effects on job performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 617–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnentag, S. Recovery, work engagement, and proactive behavior: A new look at the interface between nonwork and work. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 518–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Platania, S.; Castellano, S.; Petralia, M.C.; Digrandi, F.; Coco, M.; Pizzo, M.; Di Nuovo, S. The moderating effect of the dispositional resilience on the relationship between Post-traumatic Stress Disorder and the professional quality of life of the military returning from the peacekeeping operations. Mediterr. J. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platania, S.; Morando, M.; Santisi, G. Psychometric Properties, Measurement Invariance, and Construct Validity of the Italian Version of the Brand Hate Short Scale (BHS). Sustainability 2020, 12, 2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R.; Mitchell, M.S. Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elstad, E.; Christophersen, K.A.; Turmo, A. Social exchange theory as an explanation of organizational citizenship behaviour among teachers. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2011, 14, 405–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Bogaert, P.; Peremans, L.; van Heusden, D.; Verspuy, M.; Kureckova, V.; van de Cruys, Z.; Franck, E. Predictors of burnout, work engagement and nurse reported job outcomes and quality of care: A mixed method study. BMC Nurs. 2017, 16, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, L.A. Work engagement, moral distress, education level, and critical reflective practice in intensive care nurses. Nurs. Forum 2011, 46, 256–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, V.M.; Leslie, G.; Clark, K.; Lyons, P.; Walke, E.; Butler, C.; Griffin, M. Compassion fatigue, moral distress, and work engagement in surgical intensive care unit trauma nurses: A pilot study. Dimens. Crit. Care Nurs. 2014, 33, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLinton, S.; Afsharian, A.; Dollard, M.; Tuckey, M.R. The dynamic interplay of physical and psychosocial safety climates in frontline healthcare. Stress Health 2019, 35, 650–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshamsi, A.I.; Santos, A.; Thomson, L. Psychosocial Safety Climate Moderates the Effect of Demands of Hospital Accreditation on Healthcare Professionals: A Longitudinal Study. Front. Health Serv. 2022, 2, 824619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, M.S.; Bradley, J.C.; Wallace, J.C.; Burke, M.J. Workplace safety: A meta-analysis of the roles of person and situation factors. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 1103–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nahrgang, J.D.; Morgeson, F.P.; Hofmann, D.A. Safety at work: A meta-analytic investigation of the link between job demands, job resources, burnout, engagement, and safety outcomes. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neal, A.; Griffin, M.A. A study of the lagged relationships among safety climate, safety motivation, safety behavior, and accidents at the individual and group levels. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 946–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, R.R.; Martin, J.E.; Sears, L.E. Labor unions and safety climate: Perceived union safety values andretail employee safety outcomes. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2010, 42, 1477–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinodkumar, M.N.; Bhasi, M. Safety management practices and safety behaviour: Assessing the mediatingrole of safety knowledge and motivation. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2010, 42, 2082–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohar, D. The effects of leadership dimensions, safety climate, and assigned priorities on minor injuriesin work groups. J. Organ. Behav. 2002, 23, 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mearns, K.; Hope, L.; Ford, M.T.; Tetrick, L.E. Investment in workforce health: Exploring the implications for workforce safety climate and commitment. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2010, 42, 1445–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sio, S.; Buomprisco, G.; La Torre, G.; Lapteva, E.; Perri, R.; Greco, E.; Mucci, N.; Cedrone, F. The impact of COVID-19 on doctors’ well-being: Results of a websurvey during the lockdown in Italy. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2020, 24, 7869–7879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sio, S.; La Torre, G.; Buomprisco, G.; Lapteva, E.; Perri, R.; Corbosiero, P.; Ferraro, P.; Giovannetti, A.; Greco, E.; Cedrone, F. Consequences of COVID19-pandemic lockdown on Italian occupational physicians’ psychosocial health. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0243194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, S. An integrative model of safety climate: Linking psychological climate and work attitudes to individual safety outcomes using meta-analysis. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 83, 553–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reason, J. Managing the Risks of Organizational Accidents; Ashgate: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Dollard, M.F.; Tuckey, M.R.; Dormann, C. Psychosocial safety climate moderates the job demand-resource interaction in predicting workgroup distress. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2012, 45, 694–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Sio, S.; Buomprisco, G.; Perri, R.; Bruno, G.; Mucci, N.; Nieto, H.A.; Trovato Battagliola, E.; Cedrone, F. Work-related stress risk and preventive measures of mental disorders in the medical environment: An umbrella review. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2020, 24, 821–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirico, F.; Sacco, A.; Nucera, G.; Magnavita, N. Coronavirus disease 2019: The second wave in Italy. J. Health Res. 2021, 35, 359–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnavita, N.; Soave, P.M.; Antonelli, M. Prolonged Stress Causes Depression in Frontline Workers Facing the COVID-19 Pandemic. A Repeated Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chua, S.E. Psychological effects of the SARS outbreak in Hong Kong on high-risk health care workers. Can. J. Psychiatry 2004, 49, 391–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maunder, R.G.; Lancee, W.J.; Balderson, K.E.; Bennett, J.P.; Borgundvaag, B.; Evans, S.; Fernandes, C.M.; Goldbloom, D.S.; Gupta, M.; Hunter, J.J.; et al. Long-term psychological and occupational effects of providing hospital healthcare during SARS outbreak. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2006, 12, 1924–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Mythily, S.; Chan, Y.H.; Deslypere, J.P.; Teo, E.K.; Chong, S.A. Post-SARS psychological morbidity and stigma among general practitioners and traditional Chinese medicine practitioners in Singapore. Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. 2004, 33, 743–748. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, T.W.H.; Sorensen, K.L.; Feldman, D.C. Dimensions, antecedents, and consequences of workaholism: A conceptual integration and extension. J. Organ. Behav. 2007, 28, 111–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillet, N.; Fouquereau, E.; Vallerand, R.J.; Abraham, J.; Colombat, P. The Role of Workers’ Motivational Profiles in Affective and Organizational Factors. J. Happiness Stud. 2018, 19, 1151–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molino, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Ghislieri, C. The role of workaholism in the job demands-resources model. Anxiety Stress Coping 2016, 29, 400–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreassen, L.; Di Tommaso, M.L.; Strøm, S. Nurses and physicians: A longitudinal analysis of mobility between jobs and labor supply. Empir. Econ. 2017, 52, 1235–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Taris, T.W.; van Rhenen, W. Workaholism, burnout, and work engagement: Three of a kind or three different kinds of employee well-being? Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. 2008, 57, 173–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huyghebaert, T.; Gillet, N.; Lahiani, F.-J.; Fouquereau, E. Curvilinear effects of job characteristics on ill-being in the nursing profession: A cross-sectional study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2016, 72, 1109–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platania, S.; Caponnetto, P.; Morando, M.; Maglia, M.; Auditore, R.; Santisi, G. Cross-Cultural Adaptation, Psychometric Properties and Measurement Invariance of the Italian Version of the Job Satisfaction Scale. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2021, 11, 1073–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Platania, S.; Morando, M.; Santisi, G. Organisational Climate, Diversity Climate and Job Dissatisfaction: A Multi-Group Analysis of High and Low Cynicism. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Test Manual for the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale, Utrecht University: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2003; Unpublished manuscript, Department of Psychology.

- Balducci, C.; Fraccaroli, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. Psychometric properties of the Italian version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES-9): A cross-cultural analysis. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2010, 26, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Taris, T.W.; Bakker, A.B. It takes two to tango: Workaholism is working excessively and working compulsively. In The Long Work Hours Culture: Causes, Consequences and Choices; Burke, R.J., Cooper, C.L., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2008; pp. 203–225. [Google Scholar]

- Nonnis, M.; Cuccu, S.; Cortese, C.G.; Massidda, D. The Italian version of the Dutch workaholism scale (DUWAS): A study on a group of nurses. BPA Appl. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 278, 47–57. [Google Scholar]

- Balducci, C.; Avanzi, L.; Consiglio, C.; Fraccaroli, F.; Schaufeli, W. A cross-national study on the psychometric quality of the Italian version of the Dutch Work Addiction Scale (DUWAS). Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2017, 33, 422–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Andrews, G.; Colpe, L.J.; Hiripi, E.; Mroczek, D.K.; Normand, S.L.; Walters, E.E.; Zaslavsky, A.M. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol. Med. 2002, 32, 959–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, G.; Slade, T. Interpreting scores on the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10). Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2001, 25, 494–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, R.C.; Barker, P.R.; Colpe, L.J.; Epstein, J.F.; Gfroerer, J.C.; Hiripi, E.; Howes, M.J.; Normand, S.L.; Manderscheid, R.W.; Walters, E.E.; et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2003, 60, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, G.W.; Rensvold, R.B. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. 2002, 9, 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, L.R.; Demaree, R.G.; Wolf, G. Rwg: An assessment of within-group interrater agreement. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 306–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, W.P.; Burke, M.J.; Smith-Crowe, K. Accurate tests of statistical significance for rwg and average deviation interrater agreement indexes. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 356–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, L.R. Aggregation bias in estimates of perceptual agreement. J. Appl. Psychol. 1982, 67, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrout, P.E.; Fleiss, J.L. Intraclass correlations: Uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol. Bull. 1979, 86, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Beyond Significance Testing: Statistics Reform in the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Zyphur, M.J.; Preacher, K.J. Testing multilevel mediation using hierarchical linear models: Problems and solutions. Organ. Res. Methods 2009, 12, 695–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Towards a model of work engagement. Career Dev. Int. 2008, 13, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, M.A.; Curcuruto, M. Safety climate in organizations. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2016, 3, 191–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P.E.; Fox, S.; Penney, L.M.; Bruursema, K.; Goh, A.; Kessler, S. The dimensionality of counterproductivity: Are all counterproductive behaviors created equal? J. Vocat. Behav. 2006, 68, 446–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Oerlemans, W. Subjective well-being in organizations. In The Oxford Handbook of Positive Organizational Scholarship; Cameron, K.S., Spreitzer, G.M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 178–189. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, E.; Bryman, A.; Harley, B. Business Research Methods, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Maas, C.J.M.; Hox, J.J. Sufficient Sample Sizes for Multilevel Modeling. Methodology 2005, 1, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).