Assessing and Advancing Safety Management in Aviation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

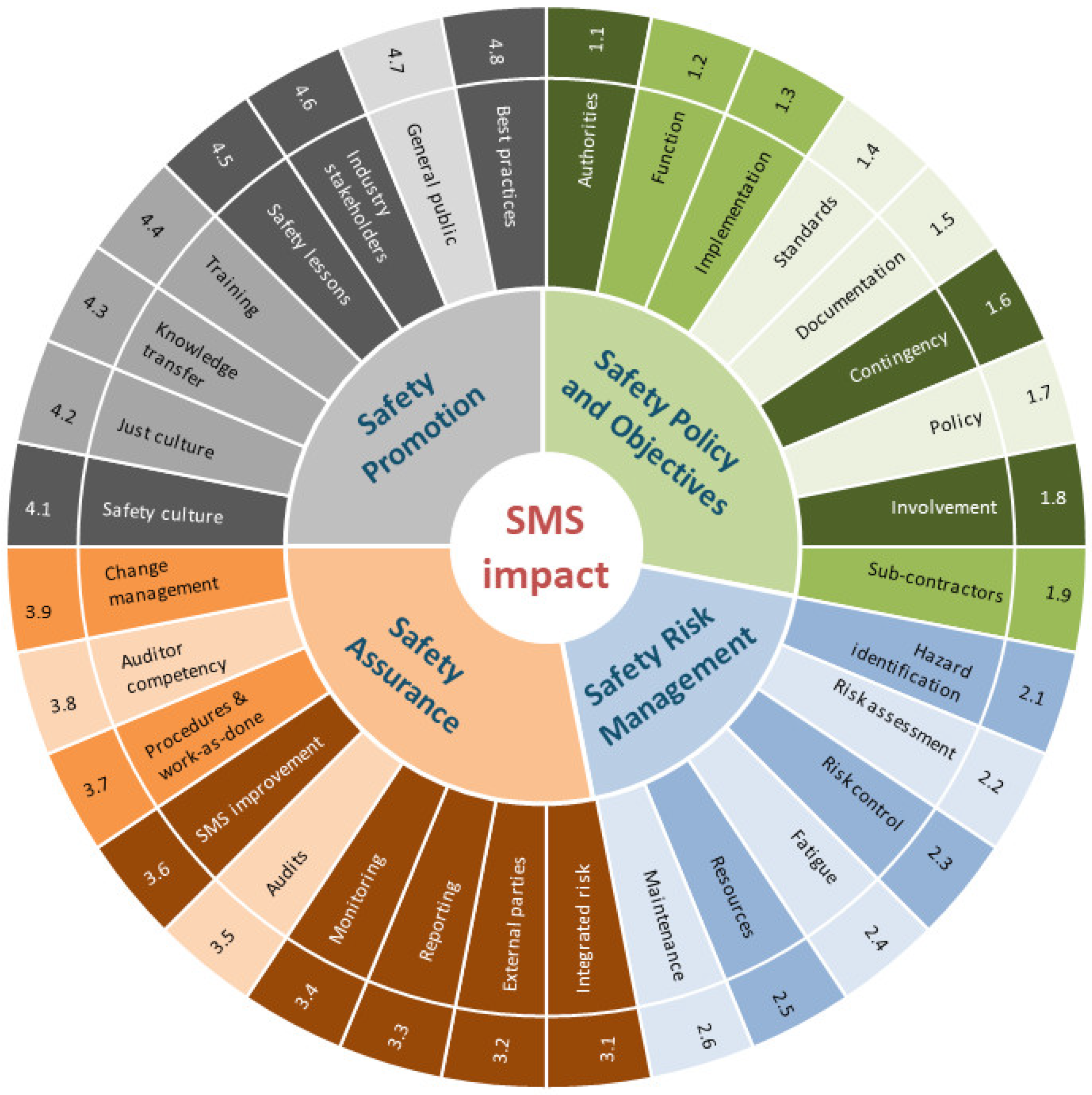

2. Assessing Safety Management Systems

2.1. Development of an SMS Maturity Assessment & Refinement Tool (SMART)

- EASA questionnaire. As part of the acceptable means of compliance and guidance material for the implementation and measurement of safety key performance indicators [12], EASA has published a questionnaire for measurement of the effectiveness of safety management. The questionnaire is based on a maturity survey in the ATM Safety Framework [13], which was developed by EUROCONTROL to support ANSPs in assessing the maturity of their SMS. This maturity survey comprises eleven study areas. The study areas are specified in more detail by one to four topics per study area and 26 topics in total. For each of these topics maturity levels are defined on a five-point scale.

- CANSO maturity scheme. The Civil Air Navigation Services Organisation (CANSO) has published a Standard of Excellence in SMS [14]. It includes a definition of SMS maturity along five levels for its thirty-six SMS objectives. The development of the CANSO scheme used the above-mentioned publications of EASA [12] and EUROCONTROL [13], but it has also added some items, and it provides some useful formulations.

- Shell SMS assessment. The SMS HSE MS self-assessment questionnaire of Shell [15] lists safety management topics and related current aviation practices, typical supporting evidence, and interpretation/guidance for aircraft operators. It consists of thirty-two topics distributed over eight groups, which are scored on a four-point scale.

2.2. SMART Application Schemes

- Single user—single organisation;

- Multiple users—single organisation;

- Multiple users—multiple organisations.

2.2.1. Single User—Single Organisation

2.2.2. Multiple Users—Single Organisation

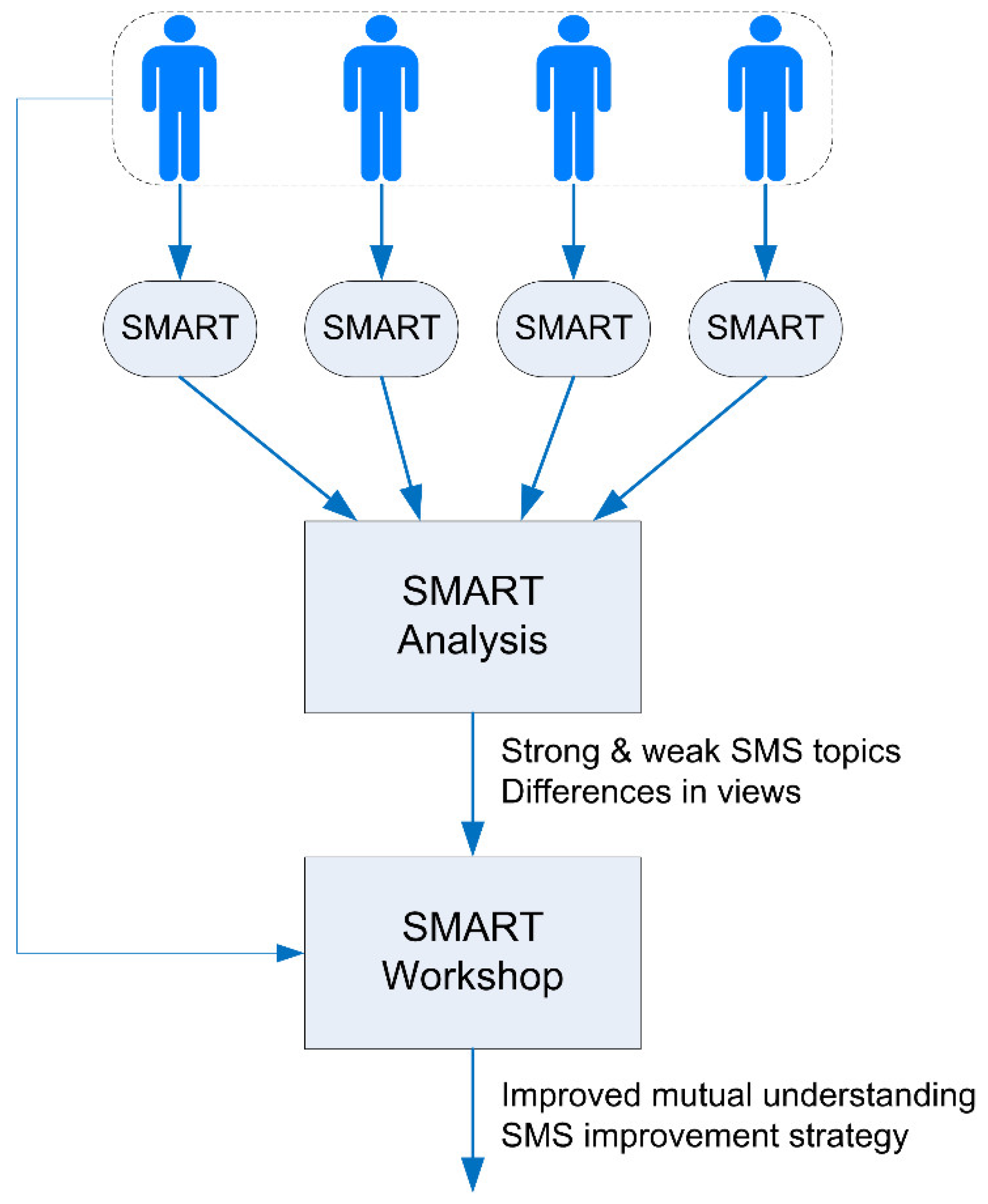

- SMART survey. The questionnaire is completed by personnel from whom it is expected to have a reasonable overview over SMS topics, such as safety managers, staff of a safety department, and other managers. The objective is to obtain a multitude of opinions about the SMS topics from different perspectives in the organisation. People are asked to provide their opinions for the scores of the SMS topics as well as explanations of their findings.

- SMART analysis. The results of the survey are collected and analysed by independent analysts with expertise in SMS. This analysis provides statistics of the scores on the various SMS topics, pointing to views on strong and weak points and to differences in opinions on the SMS topics. The analysis of the explanations provided by the participants leads to initial insights in reasons for the scores.

- SMART workshop. The results of the analysis serve as the main input for one or several workshops with participants of the survey, depending on the size and distribution of the survey group. Each workshop is facilitated by the researchers who performed the SMART analysis. The objectives of the workshop are to achieve an improved understanding between the participants of the way that the SMS works in practice in the organisation and to arrive at ways to improve the organisation’s SMS and the ways that it can be effectively applied. Discussion of the differences in the views of the participants is important to arrive at these ends.

2.2.3. Multiple Users—Multiple Organisations

3. Advancing Safety Management

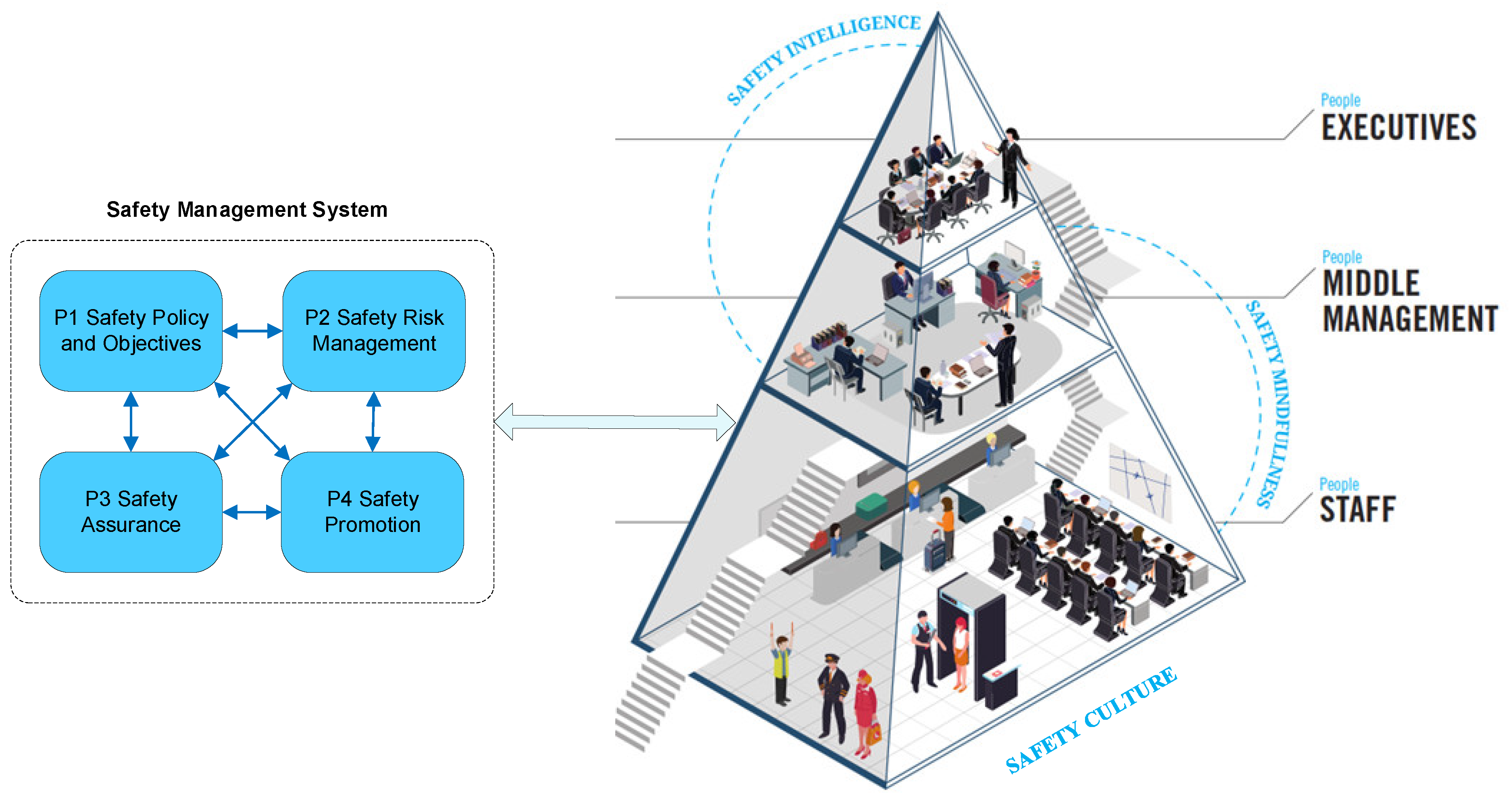

3.1. Top Management—Safety Wisdom

3.2. Middle Management

3.3. Safety Mindfulness

3.4. Safety Dashboards

3.5. Safety Culture

3.6. Agile Response Capability

3.7. SMS Impact of the Organisational Safety Approaches

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. SMS Maturity Assessment & Refinement Tool (SMART)

Appendix A.1. SMS Part P1: Safety Policy and Objectives

| 1.1 | Authorities, responsibilities, and accountabilities for safety management |

| A | No formal designation of authorities, responsibilities, or accountabilities for the management of safety exists. |

| B | Safety authorities, responsibilities, and accountabilities have been identified but not yet formalised. Line managers assume responsibility for safety. |

| C | Authorities, responsibilities, and accountabilities for the management of safety have been defined and documented. This includes an accountable executive who, irrespective of other functions, has ultimate responsibility and accountability on behalf of the organisation for the implementation and maintenance of the SMS. Delineation of responsibility for the development, oversight, and implementation of the SMS is clearly understood. |

| D | All of Level C plus: Procedures are in place to address the need to review safety authorities, responsibilities, and accountabilities after any significant organisational change. |

| E | All of Level D plus: Safety authorities, responsibilities, and accountabilities are periodically reviewed to determine whether they are suitable and effective (i.e., continuous improvement of safety management). |

| 1.2 | Safety management function |

| A | A safety management function has not yet been appointed to develop the SMS. |

| B | A safety management function has been appointed to develop and maintain the SMS. |

| C | The safety management function is independent of line management and develops and maintains an effective SMS. The safety manager has access to the resources required for the proper development and maintenance of the SMS. |

| D | All of Level C plus: The highest organisational level recognises its role in the SMS and actively supports the development, implementation, maintenance, and promotion of the SMS throughout the organisation (including support departments). |

| E | All of Level D plus: There is clear evidence that the highest organisational level plays a proactive role in the continuous improvement of the SMS. |

| 1.3 | Implementation and management of the SMS |

| A | There is no SMS in place. The need for an SMS implementation plan may have been recognised. |

| B | An SMS is partially implemented, but it does not yet meet standards established through safety regulatory requirements. A compliance gap analysis has been performed, and an SMS implementation plan has been developed towards improvement. |

| C | The essential parts of the SMS are implemented, and the organisation meets the standards established through safety regulatory requirements. The requirements expressed in the SMS implementation plan have been completed. |

| D | All of Level C plus: All parts of the SMS are implemented, and the coupling between the SMS processes have been shown to be functional. |

| E | All of Level D plus: There is continuous monitoring of the effectiveness and efficiency of the various SMS processes, and management takes effective measures to control the performance of the SMS. Latest insights on effective safety governance are used for this purpose. |

| 1.4 | Consistency with regional/international safety standards |

| A | There is little awareness of the regional or international safety standards. |

| B | There is an awareness of the regional and international safety standards. Work has started in some areas. |

| C | Regional and international safety standards are known and met as required. |

| D | All of Level C plus: There is a process in place to address the need for timely and consistent compliance with regional or international safety standards. |

| E | All of Level D plus: The organisation has a structured mechanism to address the need for ongoing and consistent compliance with regional or international safety standards. It contributes to a regional or international dialogue to improve these standards. |

| 1.5 | SMS documentation |

| A | Operations manuals do not contain any specific safety management procedures. |

| B | The documentation of SMS processes and procedures has started and is progressing according to the SMS implementation plan containing as a minimum: (a) safety policy and objectives; (b) SMS requirements; (c) SMS processes and procedures; (d) accountabilities, responsibilities, and authorities for SMS processes and procedures; and (e) SMS outputs. |

| C | The documentation of the essential parts of the SMS processes and procedures is complete. The processes and procedures ensure that the organisation is compliant with all applicable safety and regulatory requirements. |

| D | All of Level C plus: There is clear evidence that the safety and safety management documentation is readily available to all personnel in the organisation. This documentation details safety and safety management processes and procedures that meet or exceed the applicable safety and regulatory requirements. |

| E | All of Level D plus: Processes are in place and are being applied to continuously improve the SMS documentation. |

| 1.6 | Emergency/Contingency response procedures and plan |

| A | The organisation does not have redundant capabilities or back-up systems. Relevant external emergency organisations are unfamiliar with the operational hazards in the company, and the organisation has not defined an incident command structure in relationship with these external agencies. |

| B | There are procedures and some redundant capabilities and resources to cope with abnormal and unexpected situations. An incident command structure is identified. Regulatory emergency response requirements are met, while a comprehensive emergency response plan is under development. External emergency agencies are familiar with operational hazards in the company. |

| C | All primary systems have redundant capabilities, and emergency/contingency response procedures have been developed, documented, and distributed to appropriate staff. The emergency/contingency response plan is properly coordinated with the emergency/contingency response plans of those organisations it must interface with during the provision of its services. |

| D | All of Level C plus: The emergency/contingency response plan and procedures are defined in a flexible, adaptive way, properly allowing ranges of variations in the crises situation. They have been rehearsed through desktop or operational exercises. |

| E | All of Level D plus: The emergency/contingency response plans, procedures, and processes are regularly exercised and revised to keep them up-to-date. This includes exercises and coordination with all relevant external agencies, thus creating an agile response capability for the entire air transport system. |

| 1.7 | Safety policy |

| A | The need for a safety policy may have been recognised, but one does not exist. |

| B | The organisation recognises that the implemented policy needs to be signed by an accountable executive and communicated to all employees and stakeholders. A draft safety policy is available, which reflects the organisation’s commitment to safety and its priority. The policy is communicated to staff throughout the organisation and visibly endorsed by an accountable executive. |

| C | The safety policy has been finalised and signed by an accountable executive. It presents the organisation’s commitment to both safety and its adequate resourcing. There is a periodic review of the policy to assure that it continues to be relevant and appropriate. |

| D | All of Level C plus: Updates to the policy are undertaken when the accountable executive changes or if the organisation believes that the policy does not adequately address the organisation’s commitment to safety. |

| E | All of Level D plus: The organisation benchmarks its safety policy against other organisations and high reliability industries. Gaps and deficiencies are addressed in the policy and actioned through the SMS. |

| 1.8 | Senior management visibility and involvement |

| A | Senior managers do not communicate explicitly about their expectations for safety performance, and they are not involved in safety management processes. |

| B | Senior managers communicate their flight safety, occupational safety, and, where appropriate, environmental protection expectations to staff reporting to them, but they do not refer to related SMS processes. They review reactive safety indicators, such as incidents and accidents, but they are unconvinced about the value of proactive safety indicators as part of safety management. |

| C | Senior managers discuss and review with staff and subcontractors progress against meeting specific safety result targets and needed activities, usually during appraisals. They participate in the development of objectives and target setting for safety indicators. They review the progress both in the development and the content of the SMS and safety cases. They make available the resources and expertise needed for SMS tasks, evaluation, and development. |

| D | All of Level C plus: Senior managers actively participate in safety-related activities, such as training, reward and recognition schemes, safety workshops, safety conferences, and audits. They jointly develop and discuss both safety results and activity improvement targets with staff and company contractors. They are fully aware of the high priority areas for improvement identified in the SMS and the status of the follow-up remedial programme. |

| E | All of Level D plus: Senior managers drive the process for safety excellence, and they are role models for safety. They ensure that all staff have safety results and activity targets in their appraisals. They are personally involved in safety improvement efforts. |

| 1.9 | Sub-contractors |

| A | The safety competence of sub-contractors is not considered. |

| B | Sub-contractor safety competence is assessed in the light of the risks to be managed during the contract prior to the invitation to tender and award of contract. |

| C | Sub-contractor acceptance is conditional upon receiving a description of how safety risks will be systematically managed and interfaces managed on that particular activity. |

| D | All of Level C plus: Compliance with the sub-contractors own SMS is audited within an audit programme defined in the contract. Actions to be taken in the event of different levels of non-compliance are defined in the contract. |

| E | All of Level D plus: The SMS of sub-contractors are subject to continuous improvement during the course of projects and contracts in consultation with the company. |

Appendix A.2. SMS Part P2: Safety Risk Management

Appendix A.2.1. General Safety Risk Management Procedures

| 2.1 | Identification of hazards and disturbances |

| A | Disturbances of operations, including those that have a negative effect on safety (i.e., hazards), are systematically identified neither for design or changes to sociotechnical systems, nor for changing circumstances, nor on the basis of feedback from operations. |

| B | A single approach is used for the identifications of hazards, which is used for designs or changes to sociotechnical systems supporting operations. A limited number of hazards is thus identified. |

| C | A number of approaches are used for the identification of hazards as part of assessment of new designs or changes to sociotechnical systems. A broad set of hazards is thus identified. |

| D | All of Level C plus: Hazards are systematically identified on the basis of feedback from operations (coupling with safety assurance), including changes in operational circumstances. |

| E | All of Level D plus: Disturbances and variations in operations are systematically identified irrespective of the potential effect on safety. This is done for new designs, changes to sociotechnical systems, changing circumstances, and on the basis of feedback from operations. |

| 2.2 | Risk assessment for design and change |

| A | The level of risk is assessed for each identified hazard separately on a scale from low to high safety risk. This assessment is based on the judgement of a single or few people in the organisation. |

| B | The level of risk is assessed for each identified hazard separately by judgement of the likelihood of the hazard and the severity of its consequences. The assessment is based on the consultation of several people in the organisation, including operators. |

| C | The level of risk is assessed for scenarios, which represent combinations of hazards in a specific operational context, by judgement of the severity levels of the potential consequences of the scenario and the likelihood of these severity levels. The assessment is based on the consultation of several people in the organisation and on quantitative data of the operations. |

| D | All of Level C plus: For complex scenarios, models are used which represent in detail the complexity of the dynamics and interactions in the sociotechnical system. The assessment addresses a broad range of disturbances and operational variations to determine the likelihood of safety occurrences. Computer simulation of agent-based models, quantified risk models (fault and event trees), and Functional Resonance Analysis Method (FRAM) models may all be used to support such assessment. The level of uncertainty in the risk assessment results is indicated. |

| E | All of Level D plus: The models of scenarios also represent the effects on key performance areas other than safety of the identified disturbances and operational variations. As such, an overall view is attained of the implications of a scenario and of the trade-offs that an operator may need to make in balancing safety with other performance areas. |

| 2.3 | Safety risk control |

| A | There is little understanding of the need to control risk even when risks are recognised. The basic strategy is that the personnel is warned for particular risks. |

| B | Safety risk control is implemented by posing detailed requirements on human error and system failures such that the safety risk is considered acceptable. |

| C | To mitigate safety risks that are considered unacceptable, there is development by an interdisciplinary design team of new processes, equipment, training, or staffing arrangements. Residual risk levels are assessed by the design team. Managers can sign off residual risk levels over certain thresholds. |

| D | All of Level C plus: New designs for mitigation of unacceptable risks are assessed in a complete cycle of the safety risk management process to assess that the achieved risk is acceptable, and the proposed design does not introduce new hazards. This is done by an assessment team that is independent from the design team. The level of uncertainty in assessed risk levels is included in the risk tolerability decision making. |

| E | All of Level D plus: Performance variability that has been considered as normal in the safety risk assessment is used as a basis to define a range of performance indicators that reflect the work-as-done in the organisation. These performance indicators form a basis for measurement in safety assurance processes. |

Appendix A.2.2. Specific Operational SRM Issues

| 2.4 | Fatigue risk management |

| A | Fatigue-related risk is not recognised as a safety risk, which needs to be managed. |

| B | Fatigue-related risk is considered as an operational hazard, but there is no formal risk-based system by which to manage it. Policy has been developed that recognises the need for a formal risk-based approach to fatigue-related risk. |

| C | A formal risk-based system that focuses on fatigue-related risk is being implemented, which addresses responsibilities of both management and operational personnel, and methods for assessing and managing fatigue risk. |

| D | All of Level C plus: Compliance with fatigue-related risk procedures is continually assessed. Processes are in place to assess and continually improve approaches for fatigue-risk management. |

| E | All of Level D plus: The organisation uses the data and information from internal and external sources to continually improve its approach to managing fatigue-related safety risk. |

| 2.5 | Sufficiency of resources |

| A | Risks inherent in operations and emergency procedures are not considered in determining the resource levels. |

| B | Risks inherent in operations and the emergency procedures are taken into account in determining the resource levels. |

| C | The level of resources required to assure safety in terms of numbers and function of personnel are fully described in a safety case (i.e., to ensure “adequate” personnel and resources). |

| D | All of Level C plus: The actual resourcing meets the requirements described in the safety case in number and competency. |

| E | All of Level D plus: Changes to resourcing levels and competencies and associated risks are assessed as part of the change control procedure within the company. Symptoms of under-resourcing are recognised, acknowledged, and addressed. |

| 2.6 | Maintenance |

| A | The maintenance program meets the regulatory requirements. |

| B | Activities within maintenance program are commensurate to the risks they impose. Quality and integrity of the systems are proportional to the risk. |

| C | There is a data-driven assurance of quality and integrity of systems (e.g., aircraft), facilities, and equipment; effective operation and maintenance of critical equipment; and thorough records of inspection, maintenance, repair, and alteration. |

| D | All of Level C plus: There are mature reliability programs in place and a well-developed, customized maintenance program. Systems, equipment, and facilities are managed in accordance with industry best practices. |

| E | All of Level D plus: There is continuous improvement of the maintenance management based on latest insights in safety management systems. |

Appendix A.3. SMS Part P3: Safety Assurance

| 3.1 | Integrated risk management and safety-related internal interfaces for key performance areas (such as finance, quality, security, and environment) |

| A | The various management systems of key performance areas operate in isolation, and safety-related interfaces are not considered. |

| B | Safety-related relations between management systems of key performance areas are managed on an informal or ad hoc basis with a basic understanding of their boundaries and relationships. |

| C | Safety-related relations between management systems of key performance areas are managed with a solid understanding of their boundaries and relationships. |

| D | All of Level C plus: There is an integrated risk management system for all relevant key performance areas, which systematically addresses all types of risks and their relations. This includes assessment of costs associated with accidents and incidents and of costs and benefits of risk-mitigating measures. |

| E | All of Level D plus: A learning process is in place for continuous improvement of the integrated risk management system. |

| 3.2 | Safety-related interfaces with external parties |

| A | Safety-related interfaces with external parties are only considered to a limited extent. |

| B | Safety-related interfaces with external parties are managed on an ad hoc basis, and contractual arrangements are negotiated and implemented. |

| C | Formal risk management processes are used for all relations with external parties. Safety requirements are specified and documented in appropriate agreements. |

| D | All of Level C plus: External services and suppliers are surveyed/audited and systematically monitored to assure consistency with the agreements and to identify the development of new risks. Agreements and levels of coordination with external parties are revised as necessary. |

| E | All of Level D plus: A learning process is in place for continuous improvement of the safety management processes for external parties. |

| 3.3 | Reporting and investigation of safety occurrences |

| A | There is an informal system in place for reporting safety occurrences, but reports are not reviewed systematically. The reporting system is not organization wide. Investigation is done on an ad hoc basis and with little or no feedback. |

| B | There is a plan to formalise the existing reporting and investigation system. There is commitment from management to allocate resources to implement this system. The reporting system is widespread but does not yet cover the whole organisation. Feedback is given on an ad hoc basis. |

| C | The system in place is commensurate with the size of the organisation. The organisation has a complete and formal system that records all reported information relevant to the SMS, including incidents and accidents. Corrective and preventive actions are taken in response to event analysis. |

| D | All of Level C plus: Identified safety-related risks and deficiencies are actively and continuously monitored and reviewed for improvement. |

| E | All of Level D plus: Personnel who report safety occurrences and problems are empowered to suggest corrective actions, and there is a feedback process in place. |

| 3.4 | Monitoring of safety indicators |

| A | Ad hoc safety performance data related to individual incidents are available, but there is no systematic approach for measuring safety performance There are no indicators, thresholds, or formal monitoring system in place to measure safety achievements and trends. |

| B | There is a plan to implement a monitoring system. The implementation of some qualitative and quantitative techniques and indicators in certain parts of the organisation has started. |

| C | The safety monitoring system has been implemented and documented. Indicators and targets have been set, which are limited to meeting the safety regulatory requirements to verify the safety performance of the organisation. |

| D | All of Level C plus: A broader set of indicators is used, and safety performance is measured using statistical and other quantitative techniques. All indicators are tracked against thresholds/targets on a regular basis, including trend analysis. Internal comparative analysis is done, and external comparative analysis has begun. Results are used to drive further safety improvements across the organisation. |

| E | All of Level D plus: Safety indicators cover all aspects of the system/operations, and they include indicators for performance variability of work-as-done in the organisation. There are comprehensive metrics in place to measure and monitor indicators and thresholds throughout the system. Internal and external comparative analysis is well established. |

| 3.5 | Operational safety surveys and audits |

| A | There is no plan to conduct systematic operational safety surveys and audits. Operational safety surveys, audits, and gap assessments are conducted on an ad hoc basis (e.g., when deficiencies in the system or in working arrangements are found). |

| B | There is a plan in place to formalise the conduct of systematic operational safety surveys and audits. A limited number of operational safety surveys and SMS audits have been carried out. |

| C | Internal operational safety surveys and audits are conducted on a periodic basis. Based on the output of operational safety surveys and audits, a process is in place that requires the development and implementation of appropriate improvement plans. |

| D | All of Level C plus: Internal or external operational safety surveys and audits are carried out in a systematic way. There is a process in place to monitor and analyse trends and identify areas that require follow-up operational safety surveys or audits. Follow-up operational safety surveys, audits, and gap assessments are conducted in all areas affecting operational safety. Operational safety surveys and audits are actively reviewed to assess opportunities for system improvement. |

| E | All of Level D plus: Independent (external) operational safety surveys and audits are periodically conducted. The outputs from operational safety surveys and audits are incorporated as appropriate into operations. There is a process in place that requires external data to be considered when selecting areas to be subject to operational safety surveys and audits. |

| 3.6 | Auditing and improvement of SMS methods |

| A | There is no formal process that maintains the SMS, nor is there an identified authority (or authorities) responsible for the updates. SMS audits are conducted on an ad hoc basis. |

| B | A process to maintain safety management procedures exists. The authority (or authorities) responsible for the updates are partially identified. The procedures are kept up-to-date on an ad hoc basis. |

| C | SMS audits are conducted on a periodic basis. The process to maintain SMS documentation is defined and practised. |

| D | All of Level C plus: Internal or external SMS audits are carried out systematically. There is a process in place to monitor and analyse trends and identify areas that require follow-up SMS audits. SMS audits are actively reviewed to assess opportunities for system improvement. There is a formal process in place to periodically review safety and safety management procedures and ensure that they remain relevant, consistent with industry practice, and effective. The authority (or authorities) responsible for the updates are clearly identified. |

| E | All of Level D plus: Independent (external) SMS audits are periodically conducted. Changes within the organisation that could affect the safety management framework are subjected to formal review. New insights about improving SMS in the scientific literature are actively followed and the organisation participates in studies to evaluate the effectiveness of such innovations for its organisation. |

| 3.7 | Variations with respect to procedures and standards (work-as-done) |

| A | It is considered that there are no variances in the work-as-done with respect to procedures and standards. Non-compliance with procedures and standards is denied and is not recorded. |

| B | Procedures for variances with respect to procedures and standards exist, but they are impractical, and few variances are reported. |

| C | There is a system for reporting variances in work-as-done with respect to procedures and standards, which is well documented and communicated to the employees. There are records for variances for many types of work all over the organisation. |

| D | All of Level C plus: Reasons of reported variances are analysed on an ad-hoc basis. Lessons learned range from better training and education to changes in company procedures. They are systematically communicated to people who reported the variances and to others who are involved. |

| E | All of Level D plus: Safety assurance includes processes that systematically use the feedback from reported variances for organisational learning. Performance variability is explicitly considered (assumed) in safety risk management and reported variances are compared with the assumptions made. Company procedures are updated if needed, and active collaboration with industry stakeholders is sought to change standards. |

| 3.8 | Auditor competency |

| A | Company uses mainly unqualified and/or inexperienced resources for SMS audits. |

| B | Personnel involved in audits first undergo formal SMS audit training. There is a process describing the required competency for auditors. |

| C | Safety and audit personnel as well as personnel in other parts of the organisation periodically undergo audit training. |

| D | All of Level C plus: Relevant personnel undergo an audit training and competency development program. The company has been subject to external audits by peers. |

| E | All of Level D plus: Company works with individually tailored development programs aligned with best practices, and it frequently uses external audits by peers. |

| 3.9 | Management of change |

| A | No change management processes are in place although the organisation recognises that impacts of change need to be managed. |

| B | Some change management procedures exist, and they are applied on an ad hoc basis. |

| C | A systematic set of change management processes are used to address how the impact of change can be assessed from a risk perspective; how to involve stakeholders; how to document and evaluate the impacts; and who will determine whether a change is authorised or not. |

| D | All of Level C plus: Quantitative approaches for risk assessment are used. Risk control functions are being monitored following the change. |

| E | All of Level D plus: The organisation continually looks to refine its approach to change management on the basis of experience within the organisation and using knowledge of state-of-the-art in management of change. |

Appendix A.4. SMS Part P4: Safety Promotion

| 4.1 | Safety culture measurement and an improvement programme |

| A | The organisation does not see the need to have a safety culture measuring mechanism in place. |

| B | The organisation is aware of the need to have periodic measurements of safety culture in place as well as an improvement plan. However, what will be measured and when is still being defined. |

| C | Safety culture is measured, and results are available. An improvement plan addresses the need for individuals to be aware of and support the organisation’s shared beliefs, assumptions, and values regarding safety. |

| D | All of Level C plus: The organisation assesses its safety culture on a regular basis and implements improvements to any identified weaknesses. Safety culture enablers and barriers are identified, and solutions to reduce barriers are being implemented. |

| E | All of Level D plus: The organisation is gathering data on safety culture on a continuous basis, and it is constantly reflecting on the effects of all decision-making and changes on safety culture. |

| 4.2 | Promotion of a just and open culture for reporting and investigation of occurrences |

| A | Management believes there are no issues regarding the existing reporting and investigation culture and therefore does not see the need for any activity or dialogue with the staff in this area. |

| B | Discussions between staff and management to improve reporting and investigation policies and culture are underway. |

| C | Safety data-sharing and publication policies are well known and supported by the staff. Safety data are sufficiently protected from external interference within legal limits. |

| D | All of Level C plus: Within the organisation, the line between acceptable and unacceptable mistakes is clearly established and known by the staff. Just reporting and investigation culture principles are in place and systematically applied within the organisation. |

| E | All of Level D plus: There is a clear and published policy on how dialogue with judicial authorities and media is established and followed. |

| 4.3 | Knowledge transfer of safety management standards and practices |

| A | Staff have limited knowledge of the safety policy, SMS processes, and procedures. |

| B | Limited communication is presented as to why particular safety actions have been taken and/or safety management procedures introduced. Internal communications within the organisation does not focus on safety and its management. |

| C | Communication strategies are being developed to ensure that staff are aware of the safety management practices which are relevant to their position. Specific communication strategies are being implemented to address situations where procedures have changed or when critical safety action has been taken. The safety policy is prominently displayed in a language understood by all staff and contractors. All staff have a personal copy of the safety policy. |

| D | All of Level C plus: Communication mediums are regularly assessed for effectiveness. Gaps and deficiencies are acknowledged and addressed. The personal relevance of the safety policy and changes therein is communicated to all staff by their immediate supervisors or as appropriate. |

| E | All of Level D plus: Safety is a key focus of internal communication. The organisation is looking to increase the number of mediums through which safety messages are sent within the organisation. All staff are able to explain what responsibilities they have to and what they have to do in their work to fulfil the requirements of the safety policy. |

| 4.4 | Training and competency in safety and safety management |

| A | Staff and contractors are provided sparsely with training for safety and safety management activities. |

| B | Staff and contractors are provided with training and education, but spaces are limited, and planning is ad hoc. |

| C | An annual planning process for training is in place. The plan considers all staff and contractors, and the training addresses all safety management practices that they may be called upon to apply and contribute to. |

| D | All of Level C plus: There is a process for the training provider(s) to receive feedback on the effectiveness of the training programmes. Based on this feedback, the training programmes are revised to improve effectiveness. |

| E | All of Level D plus: There is regular measurement of the level of competency of staff and contractors in safety management practices, and this is used in planning and improvement of training. There is a minimum number of SMS personal that has a suitable academic background. Latest scientific insights on effective safety management and training are used for the development of the training programs. |

| 4.5 | Recording and dissemination of safety lessons learned |

| A | Safety lessons learned are known only to those who experience them. |

| B | Safety lessons are recorded and shared on an ad hoc basis rather than systematically. |

| C | The process for sharing safety lessons learned is systematic and operational, and the majority of data is shared with appropriate personnel. The rationale for taking action and making changes to procedures is explained to staff. Safety-critical information is disseminated to all appropriate staff. |

| D | All of Level C plus: All safety lessons learned are systematically shared across the organisation at all appropriate levels. Corrective actions are taken to address lessons learned. |

| E | All of Level D plus: There is clear evidence that the dissemination process of the internal lessons learned is embedded across the organisation at all levels and is periodically reviewed. |

| 4.6 | Sharing of safety information and knowledge with industry stakeholders |

| A | Safety data and information are treated as confidential and internal in the organisation as well as for industry stakeholders. |

| B | Safety data and information are shared internally, but the organisation is reluctant or unwilling to share data with industry stakeholders. |

| C | Safety data and information is shared internally, nationally, and with international bodies when it is required by regulation. |

| D | All of Level C plus: There is a clear and published policy that encourages the proactive sharing of safety-related information with other parties. |

| E | All of Level D plus: Safety data and information are actively shared internally, nationally, with recognised international bodies, and with other industry stakeholders. The organisation has a process in place to receive and act on safety data and information from external stakeholders. |

| 4.7 | Publication of safety performance information to the general public |

| A | Safety-related performance information is not made available to the public under any circumstances. |

| B | A limited amount of safety-related performance information is made available but only to selected authorities. |

| C | High-level safety-related performance information is made available to the general public according to applicable requirements. |

| D | All of Level C plus: Safety performance information not governed by applicable requirements is also made available to the public. |

| E | All of Level D plus: The organisation voluntarily makes available appropriate safety-related performance information to the general public. The achieved safety levels and trends are transparent to the general public. |

| 4.8 | Sharing and learning best practices on operational safety and SMS practices |

| A | There is no structured approach to learn and share best practices with the industry. The organisation has the capability to identify and adopt industry best practices on an ad hoc basis. There are no plans to release and share best practices with industry stakeholders. |

| B | There is an ad hoc structure in place to gather information on operational safety and SMS best practices. Some initial implementation has begun. Some internal best practices are spread across units within the organisation, but there is no systematic structure for the adoption of best practices. Sharing of best practices takes place in response to requests for assistance from industry stakeholders. |

| C | A structure has been established to identify applicable operational safety and SMS best practices from the industry to enable improvements to the SMS. Best practices are shared with industry stakeholders as required by regulation. |

| D | All of Level C plus: Industry best practices are periodically reviewed to provide the most current information, which is then assessed for applicability and adopted as appropriate. Safety-related best practices are shared to a wide extent with industry stakeholders. |

| E | All of Level D plus: All relevant best practices are readily accessible to appropriate personnel. The organisation actively cooperates with industry and academic partners in developing best practices. |

References

- International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO). Annex 19: Safety Management; International Civil Aviation Organization: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO). Safety Management Manual; International Civil Aviation Organization: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Commision Regulation (EU) No 965/2012 Laying Down Technical Requirements and Administrative Procedures Related to Air Operations; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2012.

- European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA). Acceptable Means of Compliance (AMC) and Guidance Material (GM) to Annex III—Part-ORO; European Union Aviation Safety Agency: Cologne, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). Safety Management System; Federal Aviation Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2016.

- Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). Safety Risk Management Policy; Federal Aviation Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2012.

- Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). Safety Management Systems for Aviation Service Providers; Federal Aviation Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2015.

- Reiman, T.; Rollenhagen, C. Human and organizational biases affecting the management of safety. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2011, 96, 1263–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollnagel, E. Safety-I and Safety-II: The Past and Future of Safety Management; Ashgate: Farnham, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hollnagel, E.; Woods, D.D.; Leveson, N. Resilience Engineering: Concepts and Precepts; Ashgate: Aldershot, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mearns, K.; Kirwan, B.; Reader, T.W.; Jackson, J.; Kennedy, R.; Gordon, R. Development of a methodology for understanding and enhancing safety culture in Air Traffic Management. Saf. Sci. 2013, 53, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA). AMC and GM for the Implementation and Measurement of Safety Key Performance Indicators (ATM Performance IR); European Union Aviation Safety Agency: Cologne, Germany, 2014.

- Licu, T.; Grace-Kelly, E. ATM Safety Framework Maturity Survey Methodology for ANSPs; EUROCONTROL: Brussels, Belgium, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Civil Air Navigation Services Organisation (CANSO). Standard of Excellence in Safety Management Systems; Civil Air Navigation Services Organisation: Schiphol, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Shell. HSE MS Self Assessment Questionnaire; Shell: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Stroeve, S.H.; Smeltink, J.W.; Kirwan, B. Advancing Safety in Organizations—Guidance and Supporting Material; Future Sky Safety: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Makins, N.; Kirwan, B.; Bettignies-Thiebaux, B.; Bieder, C.; Kennedy, R.; Sujan, M.; Arrigoni, V. Keeping the Aviation Industry Safe: Safety Intelligence and Safety Wisdom; Future Sky Safety: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Callari, T.C.; Bieder, C.; Kirwan, B. What is it like for a middle manager to take safety into account? Practices and challenges. Saf. Sci. 2019, 113, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieder, C.; Callari, T.C. Individual and environmental dimensions influencing the middle managers’ contribution to safety: The emergence of a ‘safety-related universe’. Saf. Sci. 2020, 132, 104946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, N.; Callari, T.C.; Baranzini, D.; Woltjer, R.; Johansson, B.J.E. Safety Mindfulness; Future Sky Safety: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, N.; Callari, T.C.; Stroeve, S.H.; Baranzini, D.; Woltjer, R.; Johansson, B.J.E. Safety Mindfulness Methodology; Future Sky Safety: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, N.; Callari, T.C.; Baranzini, D.; Mattei, F.; Citoni, S.A.; Stroeve, S.; Woltjer, R.; Johansson, B.J.E.; Oskarsson, P.A. Operational Mindfulness Manager; Future Sky Safety: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Callari, T.C.; McDonald, N.; Kirwan, B.; Cartmale, K. Investigating and operationalising the mindful organising construct in an Air Traffic Control organisation. Saf. Sci. 2019, 120, 838–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, N.; Callari, T.C.; Baranzini, D.; Mattei, F. A Mindful Governance model for ultra-safe organisations. Saf. Sci. 2019, 120, 753–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valbonesi, C.; Silvagni, S.; Kirwan, B. Safety Intelligence Tools for Executive and Middle Managers; Future Sky Safety: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kirwan, B. Aviation Safety Dashboards: Seeing What Matters; Future Sky Safety: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kirwan, B.; Reader, T.W.; Parand, A.; Kennedy, R.; Bieder, C.; Stroeve, S.; Balk, A.D. Learning Curve: Interpreting the Results of Four Years of Safety Culture Surveys. Aerosaf. World, 2019, December 2018–January 2019. Available online: https://flightsafety.org/asw-article/learning-curve-2/ (accessed on 31 January 2022).

- Reader, T.W.; Parand, A.; Kirwan, B. Mapping Safety Culture onto Processes and Practices: The Safety Culture Stack Approach; Future Sky Safety: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kirwan, B.; Reader, T.; Parand, A. The safety culture stack—The next evolution of safety culture? Saf. Reliab. 2019, 38, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Woltjer, R.; Johansson, B.J.E.; Kirwan, B. Agile Response Capability (ARC) Best Practices; Future Sky Safety: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Woltjer, R.; Johansson, B.J.E.; Svenmarck, P.; Oskarsson, P.A.; Kirwan, B. Agile Response Capability—Protocols and Guidance; Future Sky Safety: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Woltjer, R.; Johansson, B.J.E.; Oskarsson, P.A.; Svenmarck, P.; Kirwan, B. Air transport system agility: The Agile Response Capability (ARC) methodology for crisis preparedness. Infrastructures 2022, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SMS Part | Element | Description |

|---|---|---|

| P1. Safety Policy and Objectives | Management commitment | Definition of a safety policy and safety objectives. The safety policy describes the organisational commitment regarding safety, the provision of resources for implementation of the safety policy, the safety reporting procedures, and the delineation between acceptable and unacceptable behaviour. The safety objectives form the basis for safety performance monitoring in reflection of the organisation’s commitment. |

| Safety accountabilities and responsibilities | Designation of an accountable executive for the implementation and maintenance of the SMS, the definition of lines of safety accountability in the organisation, the definition of management levels with the authority to decide about safety risk tolerability, and the documentation and communication of the safety responsibilities, accountabilities, and authorities in the organisation. | |

| Appointment of key safety personnel | Appointment of a safety manager who is responsible for the implementation and maintenance of the SMS. | |

| Coordination of emergency response planning | Establishment and maintenance of an emergency response plan for accidents and incidents in aircraft operations and other aviation emergencies, which is well coordinated with the emergency response plans of related organisations. | |

| SMS documentation | Development and maintenance of an SMS manual that describes the safety policies and objectives, SMS requirements, SMS processes and procedures, and the related accountabilities, responsibilities, and authorities. This documentation also includes SMS operational records. | |

| P2. Safety Risk Management | Hazard identification | Developing and maintaining a process for the identification of hazards associated with an organisation’s aviation products or services, including reactive and proactive methods. |

| Safety risk assessment and mitigation | Developing and maintaining a process that ensures analysis, assessment, and control of the safety risks associated with identified hazards. | |

| P3. Safety Assurance | Safety performance monitoring and measurement | Developing and maintaining means to verify the organisation’s safety performance by relating safety performance indicators with safety performance targets and to validate the effectiveness of safety risk control. |

| The management of change | Developing and maintaining a process to identify changes that may affect the level of safety risk associated with an organisation’s aviation products or services and to identify and manage the safety risks that may arise from those changes. | |

| Continuous improvement of the SMS | Monitoring and assessing the effectiveness of an organisation’s SMS processes to enable continuous improvement of the overall performance of the SMS. | |

| P4. Safety promotion | Training and education | Developing and maintaining a safety training programme that ensures that the personnel is competent to perform their SMS duties. |

| Safety communication | Developing and maintaining formal means for safety communication regarding the SMS, safety-critical information, explanation of safety actions, and changes to safety procedures. |

| # | SMS Topic | Research Stream | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 | Authorities, responsibilities, and accountabilities for safety management | Top Management | Section 3.1, [17] |

| 1.6 | Emergency/contingency response procedures and plan | Agile Response Capability | Section 3.6, [31] |

| 1.8 | Senior management visibility and involvement | Top Management | Section 3.1, [17] |

| 3.1 | Integrated risk management and safety-related internal interfaces for key performance areas | Middle Management | Section 3.2, [18] |

| 3.2 | Safety-related interfaces with external parties | Safety Culture Stack | Section 3.5, [28,29] |

| 3.3 | Reporting and investigation of safety occurrences | Safety Mindfulness | Section 3.3, [20,21,22] |

| 3.4 | Monitoring of safety indicators | Safety Dashboard | Section 3.4, [25] |

| 3.6 | Auditing and improvement of SMS methods | SMART development | Section 2, [16] |

| 4.1 | Safety culture measurement and an improvement programme | Safety Culture | Section 3.5, [27] |

| 4.5 | Recording and dissemination of safety lessons learned | Safety Mindfulness | Section 3.3, [20,21,22] |

| 4.6 | Sharing of safety information and knowledge with industry stakeholders | Safety Culture Stack | Section 3.5, [28,29] |

| 4.8 | Sharing and learning best practices on operational safety and SMS practices | Safety Culture Stack | Section 3.5, [28,29] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stroeve, S.; Smeltink, J.; Kirwan, B. Assessing and Advancing Safety Management in Aviation. Safety 2022, 8, 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety8020020

Stroeve S, Smeltink J, Kirwan B. Assessing and Advancing Safety Management in Aviation. Safety. 2022; 8(2):20. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety8020020

Chicago/Turabian StyleStroeve, Sybert, Job Smeltink, and Barry Kirwan. 2022. "Assessing and Advancing Safety Management in Aviation" Safety 8, no. 2: 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety8020020

APA StyleStroeve, S., Smeltink, J., & Kirwan, B. (2022). Assessing and Advancing Safety Management in Aviation. Safety, 8(2), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety8020020