Abstract

This study examines food safety knowledge and practices of food service staff in Al Madinah hospitals, Saudi Arabia. A total of 163 food service staff participated voluntarily from 10 hospitals across the city of Al Madinah. The participants completed a questionnaire composed of three parts: General characteristics, food safety knowledge, and food safety practices. Results showed that respondents generally had good food safety knowledge with the highest pass rate of 77.9% for knowledge of cross contamination followed by 52.8% for knowledge of food poisoning, and 49.7% of knowledge of food storage. Food safety practices were also strongly observed in the hospitals with a pass rate of 92.6%. Food safety knowledge among the hospital food service staff varied with the level of education, age, and having received food hygiene/safety practices, training while food safety practices had a significant association with the level of education and food hygiene/safety practices training of the staff. Spearman rho coefficient results showed that there was a significant linear relationship between food safety practice and food safety knowledge, and that food safety knowledge significantly predicts food safety practices. This research revealed the importance of education and consistent training of food service staff in improving knowledge and thereby better and safe food handling practices, which could contribute to apply food safety in the hospitals.

1. Introduction

There is an inextricable link between nutrition, safety of food, and security of food []. Unsafe food triggers a vicious food-based cycle of both foodborne diseases, especially affecting vulnerable consumers such as elderly, sick, young children, and infants. There has been a sharp increase in concern for the safety of food among the wealthy members of various societies. However, the realistic tragedy of foodborne illnesses occurs within the developing world []. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) update in 2017, each year about 50 million people succumb to food-based ailments, leading to the death of an estimated 3,000 people. The World Health Organization [] estimates that children aged five-years and younger accounted for 40% of the foodborne ailment burden. Yet, globally the increasing awareness of foodborne illnesses as triggering significant risks to the health, social development, economic development, and safety of food continues to remain marginalized [].

Developed countries regularly launch national initiatives to educate food consumers and handlers. In developing countries, however, limited efforts are undertaken []. As indicated by an increasing number of foodborne illnesses in Saudi Arabia for example. The Ministry of Health in Saudi Arabia reported 255 incidences of food borne illnesses in the country in 2011 alone, causing 2066 people to fall ill [,]. The management of food control in the country is undertaken by the Saudi Food and Drug Authority (SFDA) and the execution of policies and procedures lies with the Saudi Arabia Standards Organisation (SASO) spanning across various committees, agencies, and administrators []. Recently, within Saudi Arabia the Department of Environmental Foods and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) standards of Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) and Hazard Analysis Critical Control Points (HACCP) have been introduced, but the application of these standards has been slow []. The issues relating to the safety of food within a healthcare environment are further critical as the consumers served within the healthcare environment include individuals who have higher healthcare risk for poor consequences, or unavoidable death due to certain disease conditions or (immunology-compromising) treatments []. Studies point out that the primary safety standards relating to the populations’ consumed food within the healthcare environments should be higher than the safety standards imposed within the restaurant or business environment []. The avoidable mishandling of food in healthcare facilities, as well as the lack of hygiene procedures can lead to the transfer of food-based ailments from the food processing stage, packaging stage, food distributing states, to food consuming. The procedure may bring out the pathogens that contaminate the consumable food, which quickly multiply to trigger avoidable health problems [].

Ensuring the safety of healthcare-based food is one of the major challenges that must be implemented at all times within the healthcare facilities, including both the small residence-type categories as well as the food-delivering entities that cater to the homes of the elderly population to the bigger healthcare facilities []. Within this scope, implementation of proper (hygienic) food preparation and handling practices for food service staff in the food establishments is vital to protect the health of the patients, staff, and other individuals from the effects of the consequences of foodborne diseases []. The challenge relating to ensuring the safety of food within the healthcare facilities may differ between facilities or within facilities, neonatal-based intensive healthcare units in the elderly population-serving facilities. However, the basic reportable requirements for the implementation of good hygienic health care practices and effective management of safety of food must be equally implemented, and in relation to the (legal) requirements of the healthcare facilities must be considered as the same with other food-serving facilities [].

Food workers must have the required skills and knowledge to ensure implementation of good hygiene practices and the safety of food concepts within the healthcare facilities. Both prior food-based work experience and education are important inputs towards ensuring workers implement healthy food-based handling tasks []. Additionally, trainings, designing policies, and setting standards can lessen the occurrence of food-based ailments caused by food handlers in food establishments []. Thus, for maintaining and enforcing the safety of food within the healthcare facilities, it is vital to evaluate the food safety knowledge and practices of food service staff. Exploring the relationship between food safety knowledge and food safety practices of food service staff and how these may be associated with their demographic profiles may further aid in developing customized training programs. This study, therefore, attempts to assess the food safety knowledge and reported practices of food service staff in Al Madinah hospitals, Saudi Arabia, together with the influence that demographic characteristics (such as nationality, gender, age, level of education, length of service and undertaken food safety trainings) of the food service staff may have on their food safety knowledge and reported practices.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Questionnaire Design

To survey the food service staff in the hospitals of Al-Madinah in Saudi Arabia a closed-ended questionnaire was designed based on suitable and relevant questions from previous validated questionnaires applied in similar studies [,,]. The questionnaire on the self-completing form contained thirty-five questions, which were divided into three parts. The first part included five questions on the demographic characteristics of each participant, such as age, educational level, gender, nationality and work experience and covered two questions on food safety training. The second part involved the questions on the knowledge of the food handler, which was further subdivided into three parts. The first sub-section covered seven questions on knowledge of food poisoning, while the second sub-part included six questions on knowledge of cross-contamination. The third sub-heading contained seven questions concerning the knowledge of food storage. The third and the last part of the questionnaire consisted of eight questions covering food handlers’ practices.

The questionnaire was validated through a pilot study amongst food safety and business management professionals to verify of the questionnaire’s accuracy so as to strengthen the survey based on their feedback received. Croncbach alpha coefficient of internal consistency was used to estimate the reliability of the questionnaire. Alpha coefficient of the instrument was 0.71. Additionally, the questionnaire was first designed in English language, and then a back to back translation into Arabic was conducted. The questionnaire was later distributed manually to the foodservice employees in the 10 hospitals in the city of Al Madinah, where participation was voluntary.

2.2. Target Participants

All foodservice staff in the hospital were the target participants for this study and were approached to contribute in the research.

2.3. Data Collection

The questionnaires were distributed to 10 hospitals (MOH hospitals, other governmental sectors hospitals, and private hospitals) and responses from the staff were collected during the period, September to December 2017. Managers of each of the selected hospitals were contacted and explained the purpose of the questionnaire. A total of 163 respondents completed the entire questionnaires. Fifteen surveys were terminated as some of the employees did not want to respond to the questionnaire erroneously and others perceived that the questionnaire could consume a lot of their time when filling it in (response rate 91.5%). The participants spent about twelve to fifteen minutes filling in the questionnaire.

2.4. Data Analysis

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 24 statistical package was used to perform the quantitative analysis of the responses of the participants. The questionnaire had twenty-eight questions about food safety knowledge and practice; for each question the participants were awarded one point when they answered correctly and a zero for incorrect answers and their percentages calculated. Additionally, the knowledge portion of the survey had subsections to test the participant’s knowledge of food poisoning, cross contamination of food and food storage. Participant responses were analysed and presented using frequency distribution. For each of the knowledge sub-section and practice section, pass rates were calculated with participants who answered more than half of the questions in the section/sub section correctly attaining a pass. Mean score and standard deviation for each of the section/sub section were also analysed.

Research highlights that when data follows a skewed distribution, non-parametric analysis is the most appropriate method for analysing the data []. Non-parametric tests (Chi-square (X2), Manne-Whitney U and Kruskale-Wallis) were therefore used for the analysis. The Chi-square (X2) test was used to compare the different demographics with the food safety knowledge and practice of the respondents to assess if there was a difference. For demographics with two independent samples, i.e. nationality, gender and food safety training, the Manne-Whitney U test was used. While the Kruskale-Wallis test was used in the case of demographics of three or more independent samples, i.e., age, education level and service experience in our survey [].

Furthermore, Spearman rho’s nonparametric correlation coefficients were computed to determine the relationship between food safety knowledge mean score and food safety practices mean scores Lastly, the effect of food safety knowledge (predictor/independent variable) on food safety practices (outcome/dependent variable) was determined using linear regression analysis.

3. Result and Discussion

3.1. Samples Profile

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of respondents, with results showing that the Saudi Arabian nationality was the highest with 60.7%. In terms of gender characteristics, females had the lead with 60.7%. Regarding the age group, the highest (51.5%) and lowest (3.1%) percentage of staffs was (20–30) and (51–60) years old, respectively. The highest educational level was that of University Degree, with 57.7%, while work experience ranging from one to seven years took the lead with 69.3% of respondents.

Table 1.

The demographic characteristics of foodservices staff.

3.2. Food Safety Training

Table 2 shows that 68.1% of all staff had received food safety training and 63.8% of the respondents understood HACCP as a system of ensuring safe food by identifying and controlling specific hazards, indicating an emphasis on food safety training in hospitals in Al Madinah. It has been argued that training universally reduces the occurrence of food-based ailments caused by food handlers in food establishments []. Studies also emphasize that food safety training can effectively improve food safety knowledge [,].

Table 2.

Food handlers’ replies on food safety training questions.

3.3. Food Handlers’ Knowledge

3.3.1. Knowledge of Food Poisoning

Table 3 summarizes food handlers’ knowledge on food poisoning. 77.9% respondents were highly knowledgeable when asked about the definition of food poisoning. While 50.3% respondents understood the difference between infection and intoxication. Respondents were almost averagely knowledgeable when asked to name the most important factors that controls the growth of bacteria (49.7%). Respondents were less knowledgeable when asked the pH range that most pathogens are likely to grow (36.2%). Additionally, when the respondents were asked about the most common bacteria that can cause foodborne diseases, less than half of total (44.2%) respondents reported the correct answer, (all of the above) which includes Salmonella, Bacillus cereus, and E. coli. However, there was no significant difference between these results (36.8%) and those who only chose Salmonella as the answer. Finally, although the majority of respondents (62.6%) had poor knowledge of how to recognize food contaminated with food poisoning bacteria, most respondents (81.6%) could identify how bacteria could be transferred to food.

Table 3.

Knowledge of foodservices staff of food poisoning.

The results indicate that, while the respondents had generalized understanding of food poisoning and its occurrence, an in-depth knowledge of its causes and control factors was missing. Similar results were observed in the case of food service staff in Iran [] and in Sicily, Italy []. A study of food handlers in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia also reported that food handlers had moderate levels of food safety knowledge []. While it reported that food handlers in a hospital kitchen in Semarang, Central Java have good knowledge in safe food handling procedures [].

3.3.2. Knowledge of Cross-Contamination

Table 4 summarizes the knowledge of respondents of cross-contamination. A high percentage (50.3%) of respondents knew what cross-contamination is. A total of 79 respondents, which represents 48.5%, were knowledgeable about why it is important to wash hands after handling raw meat and also 58.3% knew the purpose of using gloves during the preparation of food. Moreover, respondents were highly knowledgeable when asked why raw and cooked food must be separated during food preparation and refrigeration (76.1%), as well as when asked about the case of the safe use of a cutting board and utensils for fresh produce and raw meat (69.3%). However, respondents only had an average knowledge about the correct way to clean the kitchen countertop and stove (46.6%).

Table 4.

Knowledge of foodservices staff on cross-contamination.

The results indicate that the food service staff in Al Madinah Hospitals understands the concept of cross contamination and how it can be caused, yet there is scope to build their knowledge about its prevention. It also found that food service staff in hospitals in Jordan had sufficient knowledge of the cross-contamination aspect of food safety []. Other studies have also explored and concluded similar results in hospitals in Lebanon [] and Qatar [].

3.3.3. Knowledge of Food Storage

Table 5 presents a summary of the knowledge of food handlers about food storage. It shows that more than half the total respondents (63.8%) were aware of 4 °C as the recommended temperature for a refrigerator. Similarly the majority of staff (72.4%) reported that the recommended temperature of the freezer should be −18 °C and knew that the temperature of the refrigerator and the freezer should be checked every day (77.9%). However, respondents were less knowledgeable when asked whether bacteria in food could be killed by freezing at −18 °C (19%). While a majority of the staff (65%) knew that thawed meat should not be frozen for later use; respondents were less knowledgeable about where raw meat (30.7%) and fruit and vegetables (26.4%) should be stored in a fridge.

Table 5.

Knowledge of foodservices staff of food storage.

The results again highlight that, while the respondents had generalized knowledge about the correct temperature for storage, better understanding in terms of how the storage of food items must be done is needed. Similar results have been reported in case of food service staff in Iran [] as well as in hospitals in Jordan [].

3.4. Food Handlers’ Practices

Table 6 summarizes the reported food handling practices of the food service staff. Almost all the staff (94.5%) reported that they always wash their hands before food preparation. Additionally, the majority of staff (81%) wore gloves when handling food during preparation. There was a marginal difference between respondents who reported that they do not feel comfortable wearing gloves during the preparation of food and those who never wear gloves (3.7% and 3.1%), respectively. Majority of staff also indicated that they always used a mask (70.6%) and a head cap (82.2%) when preparing and distributing food. Staff also reported the correct way of washing hands (70.6%) and what to do if they have an infected wound on their hand (73%). Furthermore, 87.7% of all the respondents stated that, after handling raw meat, they wash their hands with running warm water and soap and then wipe dry. Lastly, the majority of respondents accepted that food handlers with any symptoms of communicable diseases should not prepare food for others (85.9%).

Table 6.

Food handlers answers for practices questions.

Overall, the food service staff reported good food handling practices, as was also observed in food handlers in a hospital kitchen in Semarang, Central Java []. The higher pass rate of food safety practices than food safety knowledge can be attributed to the concept of learning by doing Nursing staff of two hospitals in Sicily, Italy also reported better food handling practices than their food safety knowledge []. While in Qatar practices of the food service staff (89.7%) towards clean and safe food preparation were adequate [], the disparity between attitudes and practices of food service staff was observed in Iran [].

3.5. Association between the Demographic Characteristics of Participants and Food Safety Knowledge

The non-parametric tests (Chi-square (X2), Manne-Whitney U, and Kruskale-Wallis) of the association between the demographic characteristics of participants and food safety knowledge are presented in Table 7. Results showed that there was a significant association between nationality and food safety knowledge (p < 0.05). It was observed that 46.6% of respondents that have food safety knowledge are Saudis compared to non-Saudis at 24.5%. This observation may have resulted from the higher level of education of the staff of Saudi nationality as against the education levels of migrants. A study in peninsular Malaysia to assess food safety knowledge and food handling practices among migrant food handlers also noted that there were significant links between poor levels of food safety knowledge and respondents’ nationality []. However, other studies argue that food safety knowledge is not affected by ethnic origin [].

Table 7.

Association between the demographic characteristics of participants and Food Safety knowledge.

While the pass rate for food safety knowledge of female respondents, (46.3%) was higher than their male (24.7%) counterparts, no significant association (p ≥ 0.05) between gender and food safety knowledge was observed. This concurs with other studies that found that women were more knowledgeable and had better food safety practices than men [,]. Similarly, it was found that gender had no significant association or effect on the level of food safety knowledge among participants in Selangor, Ipoh, and Kuala Terengganu, Malaysia []. It also indicated that women have more food safety knowledge than their male counterpart, but contradicted with other studies in that it argued that there indeed is a significant association between gender and food safety knowledge [].

A significant association (p < 0.05) between age and food safety knowledge was observed. This study shows that 40.5% of respondents having food safety knowledge were within 20–30 years of age compared to older age categories. In a study done in Riyadh hospitals, Saudi Arabia, the level of knowledge of food catering staff less than 24 years of age were found higher than that of the older staff []. A similar finding was reported by [] who assessed knowledge of food safety practices among participants over the age of 18 from all over the Republic of Ireland; the participants ranging in age from 26 to 35 had the highest food safety knowledge. Other studies also state that the young had more knowledge [] and report that older age is proportional to poor food safety knowledge [,].

There was a significant association between the education levels of respondents and food safety knowledge (p < 0.05). 48.5% of the participants with a university degree had a higher level of knowledge of food safety. This is consistent with multiple research outcomes, that the higher the level of education of food handlers, the more their food safety knowledge and vice versa [,]. Moreover, studies found that, there was a significant association between food safety knowledge and participant education level []. On the contrary, however, others stated that there were no significant differences in knowledge and practices and the education background of food services staff []. Similarly, in Italian hospitals, it was found that the education level of food service staff and their food safety practices were inconsistently associated [].

No significant association (p ≥ 0.05) was observed between years of experience in food service and food safety knowledge. This may be due to the advanced training tools that new staff are equipped with which can facilitate them to have better food safety knowledge irrespective of their experience in the area. However, positive results were reported by [,] who found a significant association between the food safety knowledge of food handlers and levels of experience.

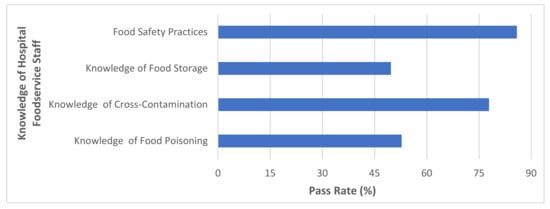

There was a significant association (p < 0.05) between having food hygiene/safety training and food safety knowledge. It was found that 52.8% of respondents who had food safety knowledge had prior food hygiene/safety practices training, compared to their counterparts (18.4%) who did not attend training courses. A similar result was reported by [] who found that the level of knowledge was significantly related to food hygiene/safety practices training among food handlers in Jordanian Military Hospitals, Jordan. Studies also reported that there was a significant improvement in the level of food safety knowledge among participants who received training [,]. Similarly, highest scores of knowledge were reported to be the most common among staff who attended training courses []. An overall comparison among the different aspects of the knowledge of food safety and practices among foodservice staff is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Pass rate for food safety knowledge and practices among foodservice staff.

3.6. Association between the Demographic Characteristics of Participants and Food Safety Practices

The non-parametric statistics of the association between the demographic characteristics of participants and food safety practices are presented in Table 8. No significant association (p ≥ 0.05) between nationality, gender, age and experience in food handling service and food safety practices was observed. No positive relationship between gender, age, education level, and food safety practices upon evaluating medical students’ knowledge and practices regarding food safety and hygiene were reported at Trakia University, Bulgaria []. However, others observed that gender and age were significantly associated with food safety practices []. Although no significant association (p ≥ 0.05) between nationality, gender, age, and experience in food handling service and food safety practices was found, females observed better safety practices than males (52.5% and 34%, respectively). It was also found that women were better than men in terms of food safety practices []. Food handlers from 20 to 30 years of age had the greatest percentage passing food safety practices at 41.7%, followed by the 31–40 age group at 31.3%.

Table 8.

Association between the demographic characteristics of participants and Food Safety Practices.

A study conducted in Calabria, Italy to evaluate food hygiene among food handlers also found that the younger the food-services staff, the more aware they were of good practices []. However, contrary to this, Reference [] stated that there was no relationship between hygiene practices and food handler age. In case of food service experience, 57.1% of participants with one–seven years of work experience of food handling service had better practices than the staff who engaged for more than seven years in food services.. However [] reported that among catering employees who had a long work experience, practices were better with respect to food hygiene.

On the other hand, significant association was found between both the education levels of the respondents (p ≤ 0.05) and having a food hygiene/safety practices training (p ≤ 0.05) with their food safety practices. Food services staff with university degrees showed high awareness with regard to practices of food safety at 52.8%. It was observed that 61.3% of the respondents who implement the right practices during food preparation had received food hygiene/safety practices, training, compared to respondents (24.5%) without prior training. These results are consistent with the outcomes reported by References [,]. Similarly, Reference [] found a strong association with regard to the relationship between the education of food handlers and positive behaviour in preserving food safety practices. Others observed that trained food services staff achieved better scores of practices than untrained staff []. Several studies have shown that there was a significant association between food handler education levels and personal hygiene practices, including food safety practices [,]. Self-reported practices of food service staffs in nursing homes and healthcare facilities found a significant association between the food safety practices of respondents and attendance at training courses on food hygiene []. However, Reference [] argued that it is not necessarily true that a high level of education develops the practices of food safety for staff.

3.7. Bivariate Correlation between Food Safety Knowledge and Food Safety Practices Using Spearman Rho Coefficient

Table 9 summarizes the linear relationship between food safety knowledge and food safety practices using Spearman rho statistics. A significant positive correlation (p ≤ 0.01) between food safety knowledge and food safety practices was observed. Thus, it implied that the higher the food safety knowledge, the better the food safety practices. Similarly, other studies [,,] show a significant positive correlation between food safety knowledge and food safety practices. Furthermore, Reference [] reported similar findings that food safety knowledge is proportional to food safety practices among food handlers. However, Reference [] have shown that food safety knowledge does not relate to food safety practices among food handlers.

Table 9.

Bivariate correlation between food safety knowledge and food safety practices using Spearman rho coefficient.

3.8. Influence of Food Safety Knowledge on Food Safety Practices Using Linear Regression Model

Table 10 summarizes the linear regression parameters. Food safety knowledge has a significant effect on food safety practices. The linear regression model established that food safety knowledge could statistically predict food safety practices (F = 47.45; df = 1; p = 0.000). Food safety knowledge account for 2.23% variability in food safety practices. Thus, this outcome shows that participants with a mean of 12.06 of food safety knowledge are expected to have on average a food safety practice of 3.375. This is consistent with the report in Reference [] who reported that the odds of bad food safety practices were 15.4 times higher in respondents with poor food safety knowledge than in respondents with sufficient food safety knowledge.

Table 10.

Influence of food safety knowledge on food safety practice using a linear regression model.

3.9. Influence of Demographic Characteristics on Food Safety Knowledge and Food Safety Practices Using Linear Regression Model

Table 11 summarizes the linear relationship between the demographic characteristics and food safety knowledge and food safety practices. The multiple linear regression models were significant (p < 0.05), and the independent variables accounted for 25.9% of food safety knowledge (R2 = 0.259) and 21.8% of food safety practices (R2 = 0.218). The results indicate a significant positive correlation between education and food safety knowledge and food safety practices as well as between length of service and food safety knowledge. The results are consistent with studies that found a significant positive relationship between participant education level and food safety knowledge [,,] and food safety practices []. Positive relationship was also reported by [] between the food safety knowledge of food handlers and levels of experience. The results outline that nationality, gender, age and training are not positively correlated with food safety knowledge and food safety practices of food service staff in Al Madinah Hospital in Saudi Arabia. Similar findings have been reported that food safety knowledge and practices are not affected by ethnic origin [], gender [], age and trainings [,].

Table 11.

Influence of demographic characteristics on food safety knowledge on food safety practice using a linear regression model.

4. Conclusions

This study assessed the food safety knowledge and practices of food service staff in Al Madinah hospitals, Saudi Arabia. The obtained results can inform the design of education and training programs, setting up of standards and policies and inspection regimes that can lead to better and safer food handling practices in healthcare settings in Saudi Arabia. Food safety efforts generally tend to focus on laboratory examination and physical investigation of the end product, while food handling and practices gets limited attention. As established in this study, food handlers in healthcare settings need effective and regular education and training to safeguard individuals with higher healthcare risk. It is therefore recommended that authorities, hospital management, researchers, educators, and food safety communicators should work towards educating and supporting the hospital food service staff to advance their food safety knowledge to safer food practices.

Author Contributions

A.P. and A.K.J. conceptualized the research, conducted formal analysis, supervised and conducted review and editing of the article. N.A.A. undertook the investigation, methodology and wrote the original draft of the article.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support and facilities provided by Dublin Institute of Technology, Dublin, Ireland. The researcher Nada Alqurashi would also like to thank King Abdullah scholarship program for the financial support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. WHO Fact Sheet. Available online: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs399/en/ (accessed on 17 November 2017).

- Omari, R.; Frempong, G. Food safety concerns of fast food consumers in urban Ghana. Appetite 2016, 98, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Joint External Evaluation of IHR Core Capacities of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: Mission Report; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Haapala, I.; Probart, C. Food safety knowledge, perceptions, and behaviors among middle school students. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2004, 36, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health Portal, Saudi Arabia. Available online: http://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/Pages/default.aspx (accessed on 17 July 2018).

- Ayaz, W.; Priyadarshini, A.; Jaiswal, A. Food Safety Knowledge and Practices among Saudi Mothers. Foods 2018, 7, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Agricultural Organization. National Food Safety Systems in the Near East–A Situational Analysis. Available online: ftp://ftp.fao.org/es/esn/food/meetings/NE_wp3_en.pdf (accessed on 4 July 2018).

- Al-Kandari, D.; Jukes, D.J. A situation analysis of the food control systems in Arab Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries. Food Control 2009, 20, 1112–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrie, D. The provision of food and catering services in hospital. J. Hosp. Infect. 1996, 33, 13–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, B.; Hunter, P. The Microbiological Safety of Food in Healthcare Settings; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Arduser, L.; Brown, D.R. HACCP and Sanitation in Restaurants and Food Service Operations, Atlantic Publishing Company. Available online: http://sphweb.bumc.bu.edu/otlt/MPH-Modules/BS/BS704_/BS704_Nonparametric2.html (accessed on 17 November 2017).

- Lund, B.M. Microbiological food safety for vulnerable people. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 10117–10132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumarjan, N.; Mohd, Z.M.S.; Mohd, R.S.; Zurinawati, M.; Mohd, H.M.H.; Saiful, B.M.F.; Hanafiah, M. Hospitality and Tourism: Synergizing Creativity and Innovation in Research; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Acikel, C.H.; Ogur, R.; Yaren, H.; Gocgeldi, E.; Ucar, M.; Kir, T. The hygiene training of food handlers at a teaching hospital. Food Control 2008, 19, 186–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreb, N.A.; Priyadarshini, A.; Jaiswal, A.K. Knowledge of food safety and food handling practices amongst food handlers in the Republic of Ireland. Food Control 2017, 80, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, S.; Wang, X.; Yang, Y.; Bai, L. Knowledge of food safety and handling in households: A survey of food handlers in Mainland China. Food Control 2016, 64, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, L. Nonparametric Test. Boston University School of Public Health, 2016. Available online: http://sphweb.bumc.bu.edu/otlt/MPH-Modules/BS/BS70_Nonparametric/BS704_Nonparametric2.html (accessed on 1 January 2017).

- Lindgreen, A.; Hingley, M.K.; Angell, R.J.; Memery, J. A Stakeholder Approach to Managing Food: Local, National and Global Issues; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Askarian, M.; Kabir, G.; Aminbaig, M.; Memish, Z.A.; Jafari, P. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of food service staff regarding food hygiene in Shiraz, Iran. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2004, 25, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buccheri, C.; Casuccio, A.; Giammanco, S.; Giammanco, M.; La Guardia, M.; Mammina, C. Food safety in hospital: Knowledge, attitudes and practices of nursing staff of two hospitals in Sicily, Italy. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2007, 7, 3745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.K.; Abdul Halim, H.; Thong, K.L.; Chai, L.C. Assessment of food safety knowledge, attitude, self-reported practices, and microbiological hand hygiene of food handlers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lestantyo, D.; Husodo, A.H.; Iravati, S.; Shaluhiyah, Z. Safe Food Handling Knowledge, Attitude and Practice of Food Handlers in Hospital Kitchen. Int. J. Public Health Sci. 2017, 6, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osaili, T.M.; Obeidat, B.A.; Hajeer, W.A.; Al-Nabulsi, A.A. Food safety knowledge among food service staff in hospitals in Jordan. Food Control 2017, 78, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bou-Mitri, C.; Mahmoud, D.; Gerges, N. El.; Jaoude, M.A. Food safety knowledge, attitudes and practices of food handlers in lebanese hospitals: A cross-sectional study. Food Control 2018, 94, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Kaabi, S.K.; lbrahim, A.A.E.; Salama, R.E. Assessment of Knowledge, Attitude and Practice of Food Safety Among Food Service Staff at Hamad General Hospital in 2006. Qatar Med. J. 2010, 19, 14–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woh, P.Y.; Thong, K.L.; Behnke, J.M.; Lewis, J.W.; Zain, S.N.M. Evaluation of basic knowledge on food safety and food handling practices amongst migrant food handlers in Peninsular Malaysia. Food Control 2016, 70, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patah, M.O.R.A.; Issa, Z.M.; Nor, K.M. Food Safety Attitude of Culinary Arts Based Students in Public and Private Higher Learning Institutions (IPT). Int. Educ. Stud. 2009, 2, 168–178. [Google Scholar]

- Carbas, B.; Cardoso, L.; Coelho, A.C. Investigation on the knowledge associated with foodborne diseases in consumers of northeastern Portugal. Food Control 2013, 30, 54–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fein, S.B.; Lando, A.M.; Levy, A.S.; Teisl, M.F.; Noblet, C. Trends in US consumers’ safe handling and consumption of food and their risk perceptions, 1988 through 2010. J. Food Prot. 2011, 74, 1513–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabrizi, J.S.; Nikniaz, L.; Sadeghi-Bazargani, H.; Farahbakhsh, M.; Nikniaz, Z. Determinants of the food safety knowledge and practice among Iranian consumers: A population-based study from northwest of Iran. Br. Food J. 2017, 119, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mohaithef, M. Food Hygiene in Hospitals: Evaluating Food Safety Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices of Foodservice Staff and Prerequisite Programs in Riyadh’s Hospitals, Saudi Arabia. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Angelillo, I.F.; Viggiani, N.M.; Rizzo, L.; Bianco, A. Food handlers and foodborne diseases: Knowledge, attitudes, and reported behavior in Italy. J. Food Prot. 2000, 63, 381–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yap, L.; Francis, S.L.; Shelley, M.; Lillehoj, C.; Montgomery, D.; Winham, D.M. Risky Food Handling Practices among Community-Residing Older Adults. FASEB J. 2016, 30, 674–677. [Google Scholar]

- Smigic, N.; Djekic, I.; Martins, M.L.; Rocha, A.; Sidiropoulou, N.; Kalogianni, E.P. The level of food safety knowledge in food establishments in three European countries. Food Control 2016, 63, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibanyoni, J.J.; Tshabalala, P.A.; Tabit, F.T. Food safety knowledge and awareness of food handlers in school feeding programmes in Mpumalanga, South Africa. Food Control 2017, 73, 1397–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Mutalib, N.A.; Abdul-Rashid, M.F.; Mustafa, S.; Amin-Nordin, S.; Hamat, R.A.; Osman, M. Knowledge, attitude and practices regarding food hygiene and sanitation of food handlers in Kuala Pilah, Malaysia. Food Control 2012, 27, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nee, S.O.; Sani, N.A. Assessment of knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP) among food handlers at residential colleges and canteen regarding food safety. Sains Malays. 2011, 40, 403–433. [Google Scholar]

- Sharif, L.; Obaidat, M.M.; Al-Dalalah, M.R. Food hygiene knowledge, attitudes and practices of the food handlers in the military hospitals. Food Nutr. Sci. 2013, 4, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Cunha, D.T.; Stedefeldt, E.; de Rosso, V.V. The role of theoretical food safety training on Brazilian food handlers’ knowledge, attitude and practice. Food Control 2014, 43, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebouças, L.T.; Santiago, L.B.; Martins, L.S.; Menezes, A.C.R.; Araújo, M.D.P.N.; de Castro Almeida, R.C. Food safety knowledge and practices of food handlers, head chefs and managers in hotels’ restaurants of Salvador, Brazil. Food Control 2017, 73, 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, M.; Mahanta, L.B.; Goswami, J.S.; Mazumder, M.D. Will capacity building training interventions given to street food vendors give us safer food? A cross-sectional study from India. Food Control 2011, 22, 1233–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratev, D.; Odeyemi, O.A.; Pavlov, A.; Kyuchukova, R.; Fatehi, F.; Bamidele, F.A. Food safety knowledge and hygiene practices among veterinary medicine students at Trakia University, Bulgaria. J. Infect. Public Health 2017, 10, 778–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mekasha, T.; Neela, S.; Kumela, D. Food safety knowledge, practice and attitude of food handlers in traditional hotels of Jimma Town, Southern Ethiopia. Ann. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 17, 507–517. [Google Scholar]

- Angelillo, I.F.; Viggiani, N.M.; Greco, R.M.; Rito, D. HACCP and food hygiene in hospitals knowledge, attitudes, and practices of food-services staff in Calabria, Italy. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2001, 22, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howes, M.; McEwen, S.; Griffiths, M.; Harris, L. Food handler certification by home study: Measuring changes in knowledge and behavior. Dairy Food Environ. Sanit. 1996, 16, 737–744. [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre, L.; Vallaster, L.; Wilcott, L.; Henderson, S.B.; Kosatsky, T. Evaluation of food safety knowledge, attitudes and self-reported hand washing practices in FOODSAFE trained and untrained food handlers in British Columbia, Canada. Food Control 2013, 30, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, F.H.; Chik, C.T.; Muhammad, R.; Yusoff, N.M. Food safety knowledge and personal hygiene practices amongst mobile food handlers in Shah Alam, Selangor. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 222, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jianu, C.; Goleţ, I. Knowledge of food safety and hygiene and personal hygiene practices among meat handlers operating in western Romania. Food Control 2014, 42, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, M.; Morancie, A. Food safety knowledge of foodservice workers at a university campus by education level, experience, and food safety training. Food Control 2015, 50, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sani, N.A.; Siow, O.N. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of food handlers on food safety in food service operations at the Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. Food Control 2014, 37, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosnani, A.H.; Son, R.; Mohhidin, O.; Toh, P.S.; Chai, L.C. Assessment of knowledge, attitude and practices concerning food safety among restaurant workers in Putrajaya, Malaysia. Food Sci. Qual. Manag. 2014, 32, 20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Baş, M.; Ersun, A.Ş.; Kıvanç, G. The evaluation of food hygiene knowledge, attitudes, and practices of food handlers’ in food businesses in Turkey. Food Control 2006, 17, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacholewicz, E.; Barus, S.A.S.; Swart, A.; Havelaar, A.H.; Lipman, L.J.; Luning, P.A. Influence of food handlers’ compliance with procedures of poultry carcasses contamination: A case study concerning evisceration in broiler slaughterhouses. Food Control 2016, 68, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).