Bayesian Network-Based Failure Risk Assessment and Inference Modeling for Biomethane Supply Chain

Abstract

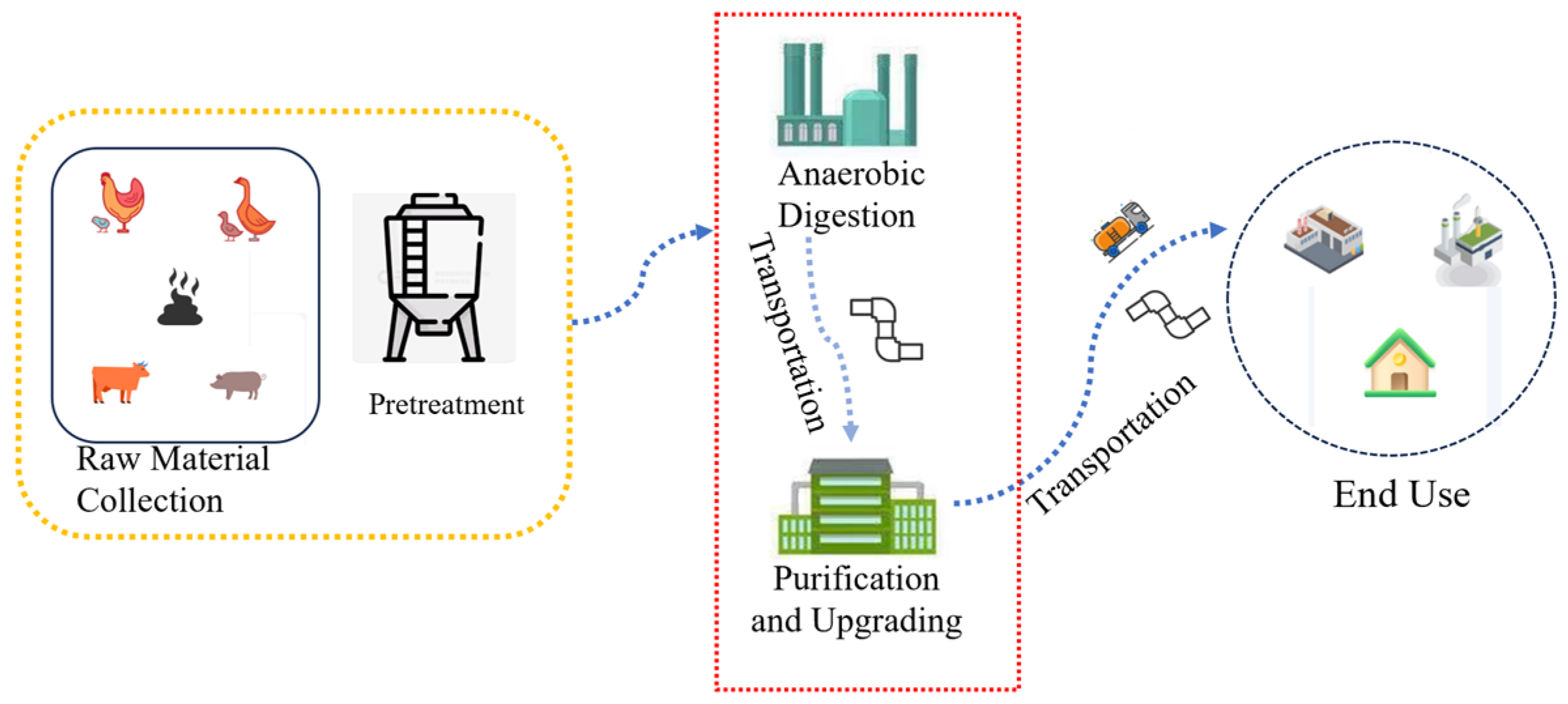

1. Introduction

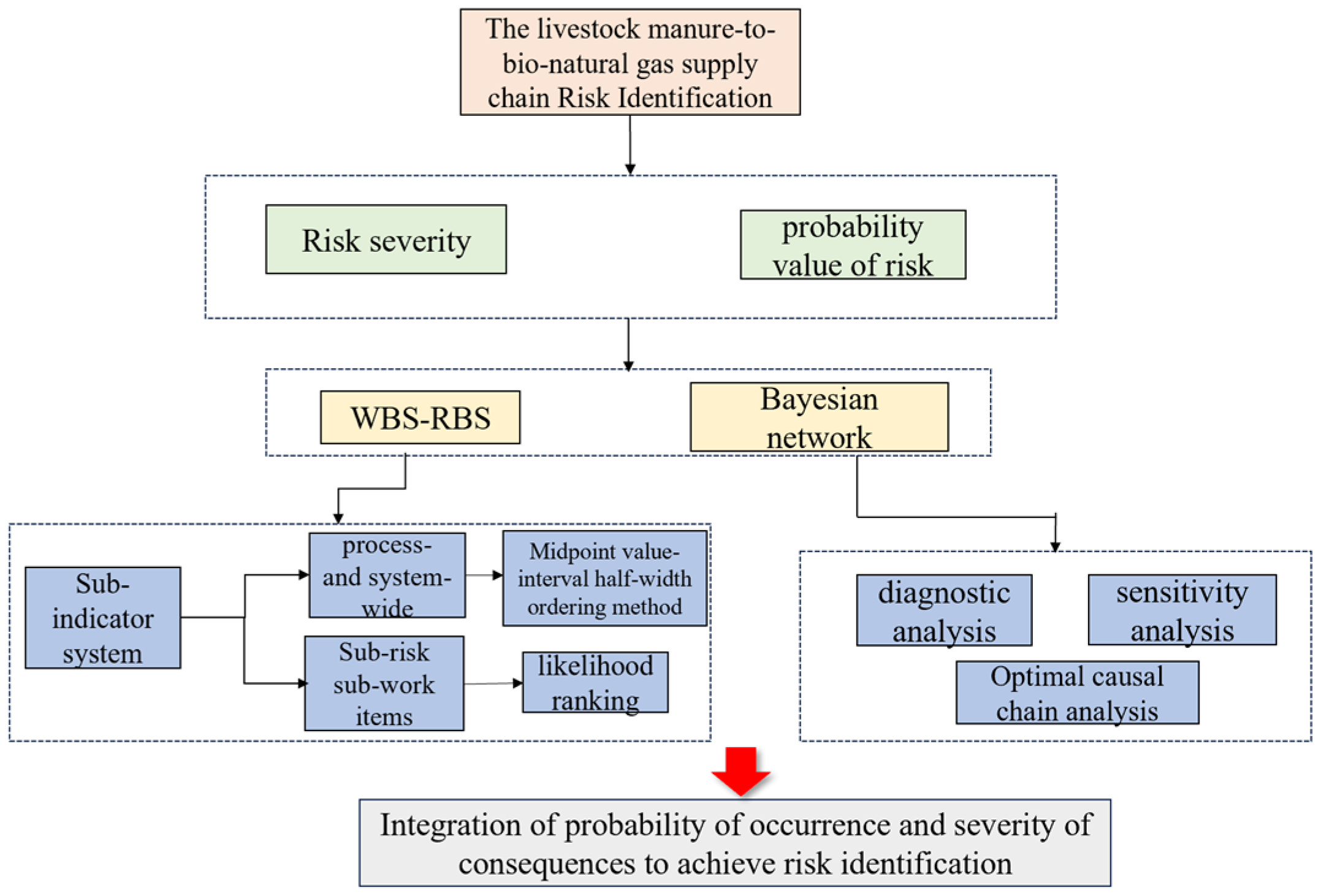

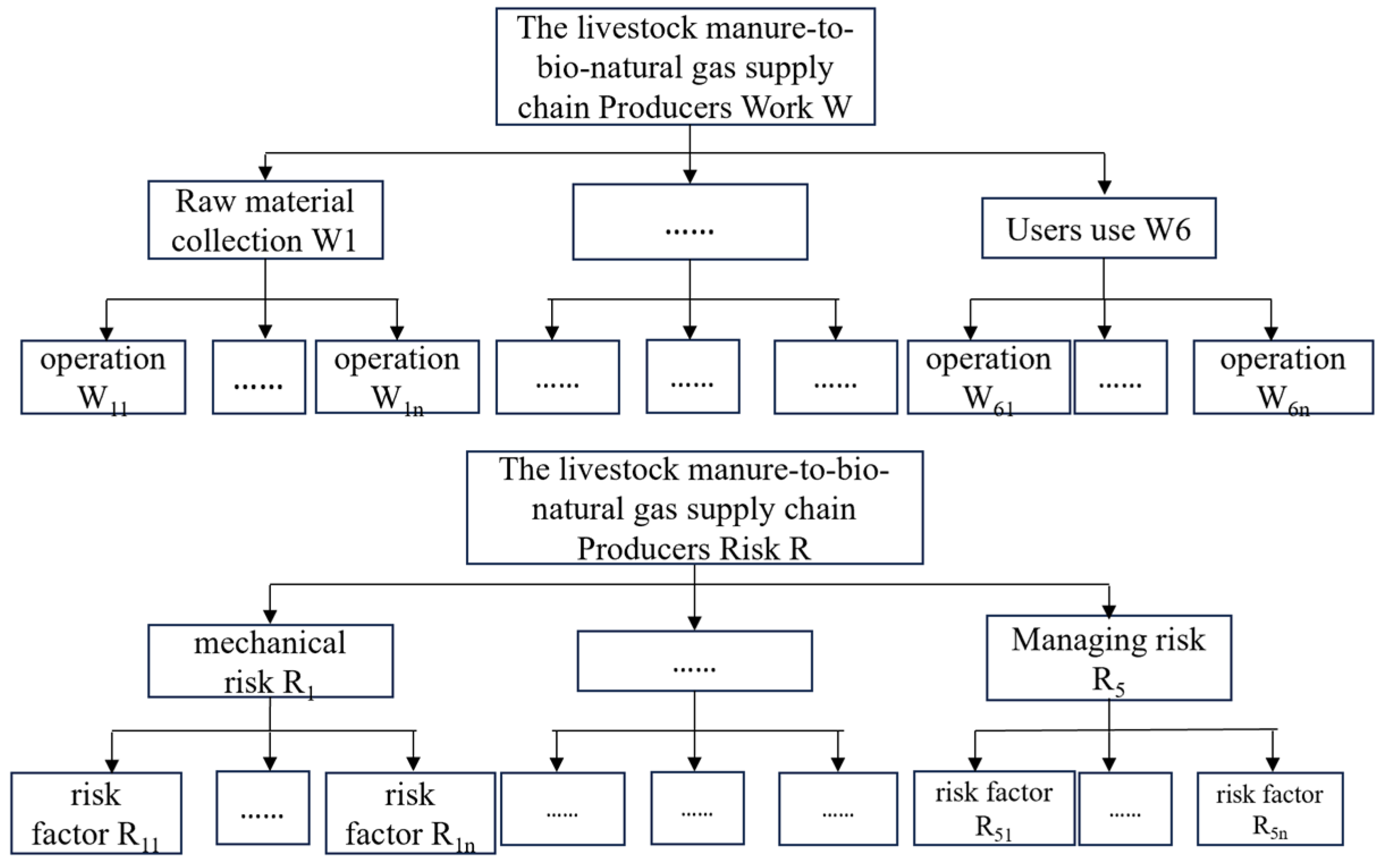

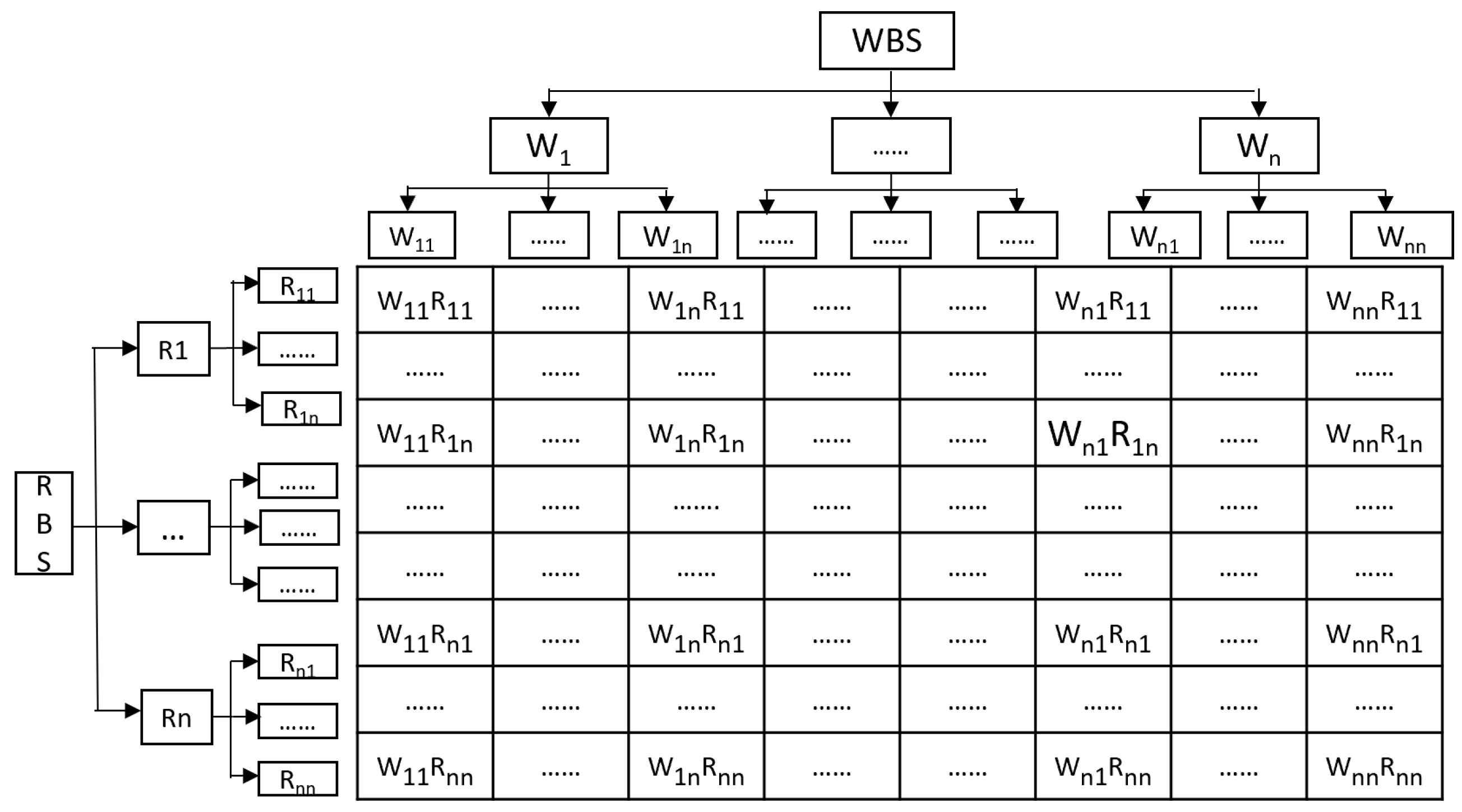

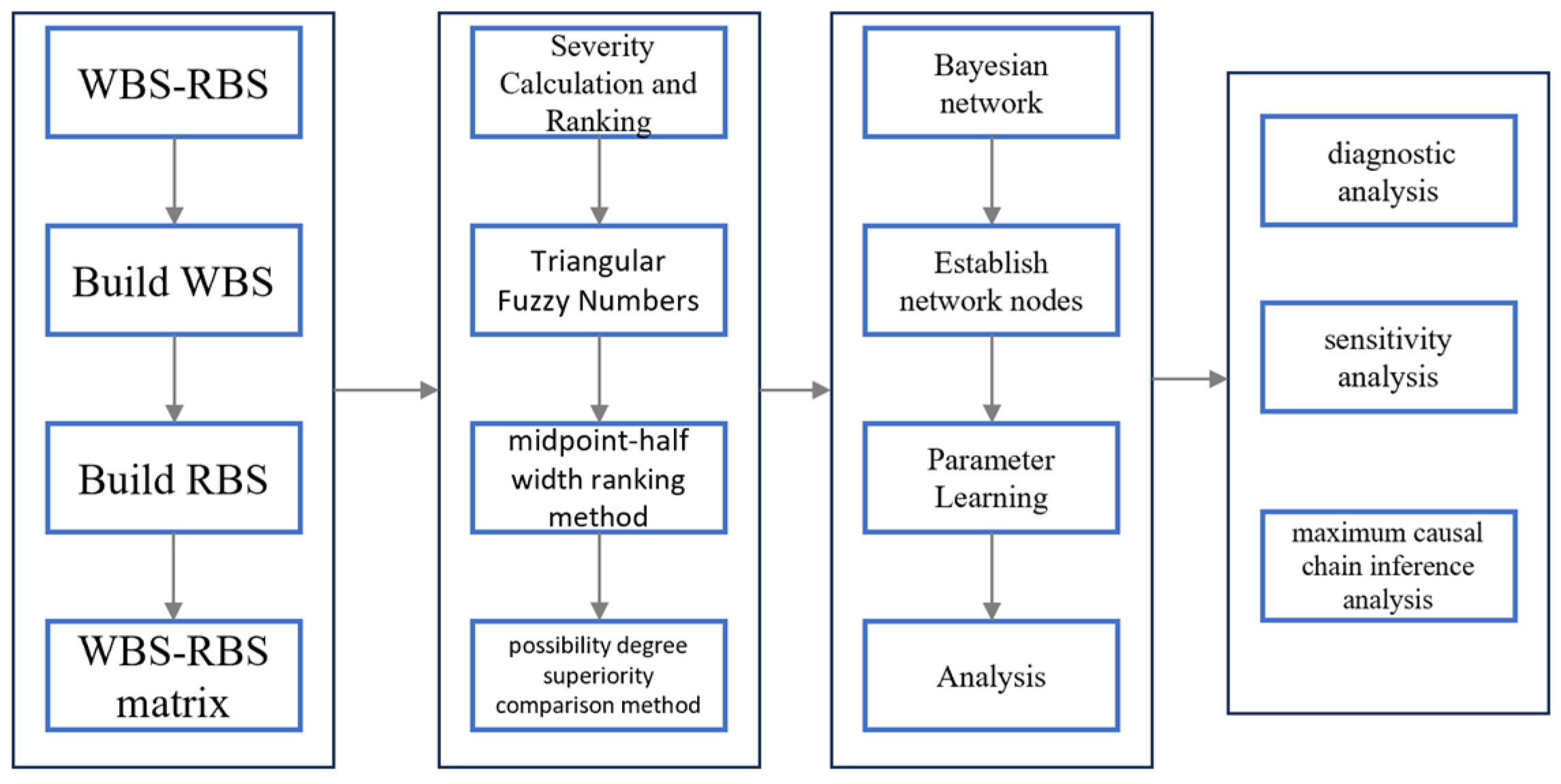

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Establishment of the Indicator System

2.2. Severity Calculation and Ranking

2.3. Bayesian Network (BN)

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Case Study: Data and Process

3.2. WBS-RBS Sub-Indicator Identification

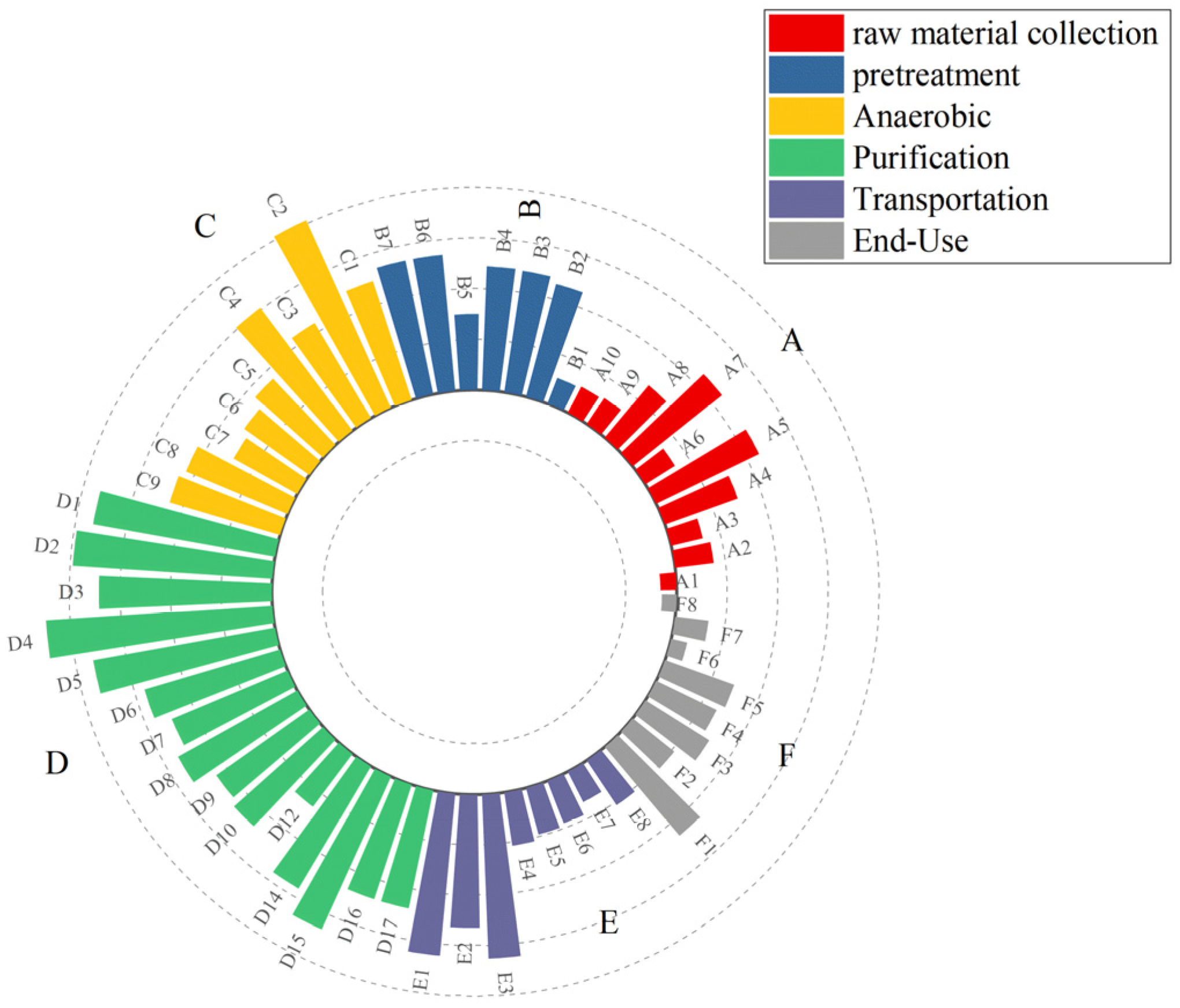

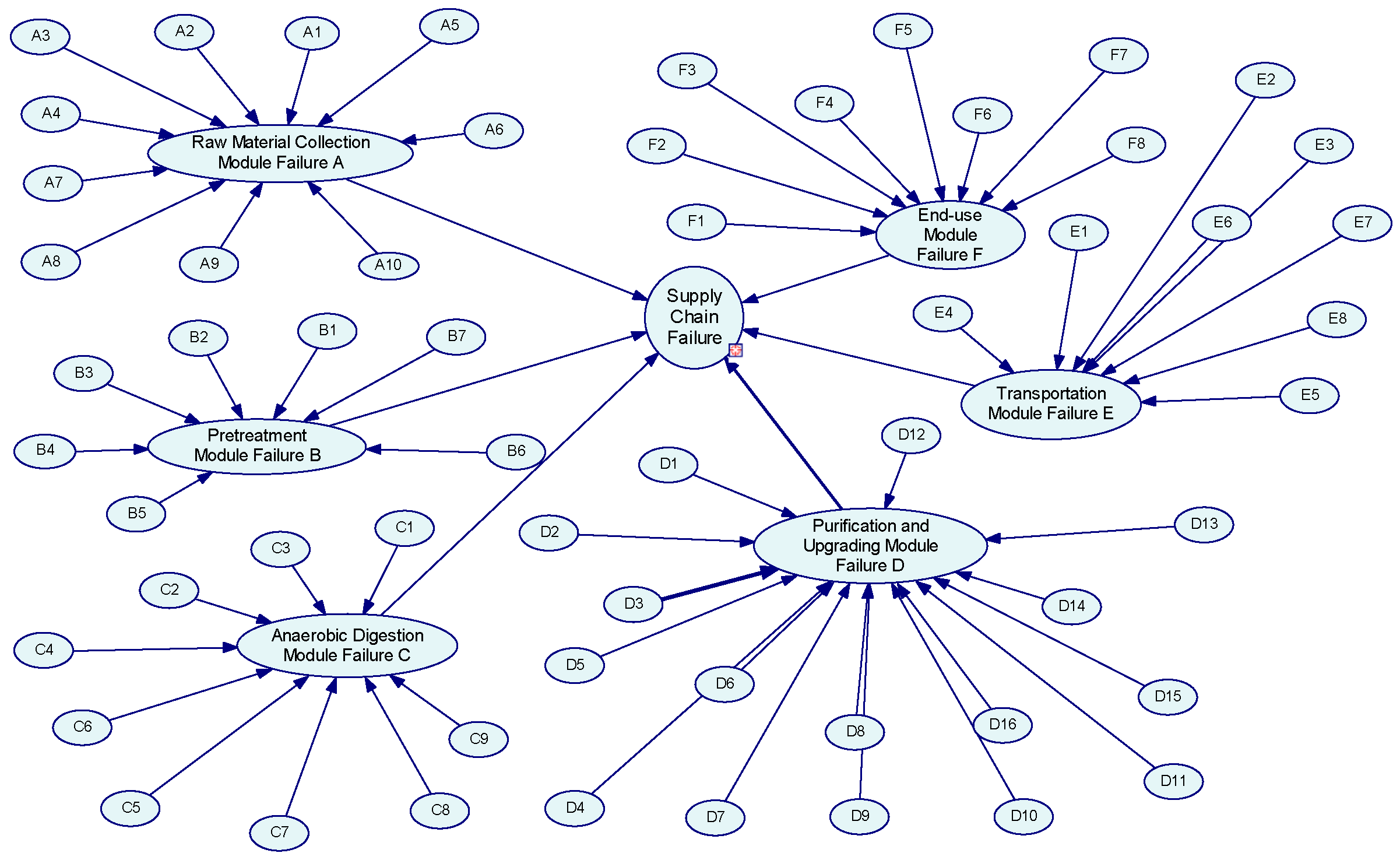

- (1)

- From the perspective of the raw material collection module, the risk factors that may cause supply chain failure in the raw material collection module are mainly divided into mechanical injury, fire risk, biological hazard, environmental risk and management risk. Mainly including: Mechanical injury in solid–liquid separation A1 (W111 coupled with R15); Biological hazard of livestock manure to human body A2 (W111 coupled with R31); Improper sewage collection and disposal A3 (W121 coupled with R31, R32); Improper treatment of harmful gases during incineration A4 (W131 coupled with R21); Improper preservation during transportation of dead livestock manure A5 (W131 coupled with R22); Improper handling by personnel leading to contact with viruses/bacteria A6 (W131 coupled with R31, R33); Unreasonable deep burial design A7 (W132 coupled with R31); Deep burial leakage caused by natural disasters A8 (W132 coupled with R41); Improper harmless treatment operation A9 (W133 coupled with R23); Handling pollution and human harm caused by various heavy metals A10 (W14 with R32).

- (2)

- From the perspective of the pretreatment module, the factors causing module failure include: Mechanical injury caused by improper operation during solid–liquid separation process B1 (W211 coupled with R15); Corrosiveness caused by pH adjustment process B2 (W212 coupled with R36); Operator poisoning caused by odor overflow B3 (W214 coupled with R33); Mechanical injury to operators caused by improper crushing operation B4 (W215 coupled with R11, R13, R15); Incomplete disinfection leading to virus/bacteria transmission and personnel injury B5 (W216 coupled with R22); Mechanical failure injury in feed buffer system B6 (W221 coupled with R11, R13, R15); Mechanical injury to personnel caused by pump delivery failure or improper operation B7 (W222 coupled with R11, R14, R15).

- (3)

- Anaerobic Digestion Module. Risk factors causing module failure include: Mechanical agitator operation failure injury C1 (W31 coupled with R11, R14, R15); Fire risk during anaerobic digestion C2 (W31 coupled with R21); Mechanical agitator failure due to poor management/organization C3 (W31 coupled with R51, R52); Chemical toxicity from sulfide leakage during pre-desulfurization C4 (W32 coupled with R22, R33, R35, R36); Operator burns from improper coil contact C5 (W32 coupled with R22, R33, R35, R36); Burns due to inadequate heating coil supervision C6 (W33 coupled with R12, R22); Mechanical failure in feed buffer system C7 (W34 coupled with R11, R13, R15, R21); Operational impacts from poor supervision C8 (W34 coupled with R51); Poor equipment pipeline design C9 (W34 coupled with R52).

- (4)

- Purification and Upgrading Module. Risk factors include: Chemical toxicity from leaks D1 (W41 coupled with R23); Oxygen deficiency from sulfur compound leaks D2 (W41 coupled with R34, R35); Equipment corrosion from improper desulfurization D3 (W41 coupled with R36); Combustion from ignition sources D4 (W41 coupled with R21); Oxygen deficiency from nitrogen compound leaks D5 (W42 coupled with R23); Ammonia poisoning from corrosion leaks D6 (W42 coupled with R34, R35); Operator burns from improper dehumidifier contact D7 (W43 coupled with R12); Physical injuries from operational errors D8 (W43 coupled with R13); Equipment explosion from overheating D9 (W43 coupled with R22); Leakage incidents D10 (W43 coupled with R23, R34); Other solid handling operations Mechanical failure injury D11 (W44 coupled with R15); Solid treatment failures from poor management D12 (W44 coupled with R51, R52); Explosions from improper flare operation D13 (W45 coupled with R21, R22); Harmful gas leaks D14 (W45 coupled with R23); Oxygen deficiency D15 (W45 coupled with R34); Accidents from pipeline design flaws D16 (W45 coupled with R42).

- (5)

- Transportation Module. Risk factors include: Leaks from operational errors E1 (W51 coupled with R22, R23); Explosions when leaks meet ignition sources E2 (R51 coupled with R21); Operator frostbite from leaks E3 (W51 coupled with R22); Insufficient safety training/supervision E4 (W51 coupled with R52); Pipeline explosions from leaks/ignition E5 (W52 coupled with R21, R22, R23, R42, R52); Poor pipeline network design E6 (W52 coupled with R42); Management deficiencies E7 (W52 coupled with R52); Natural disaster damage E8 (R41).

- (6)

- End-Use Module Risk factors include: Fuel supply explosions F1 (W61 coupled with R21); Consequences of poor pipeline design F2 (W61 coupled with R42); Insufficient safety awareness F3 (W61 coupled with R52); Inadequate supervision F4 (W61 coupled with R53); Burns from circulating water pipes F5 (W62 coupled with R21); Mechanical explosions from overpressure F6 (W62 coupled with R42); Chain explosions from poor heating pipe management F7 (W62 coupled with R52); Combustion explosions during pipeline injection F8 (W63 coupled with R21); The complete indicator system and full process risk values are shown in Figure 6. The detailed indicators are listed in Table S1 in the Supplementary Materials.

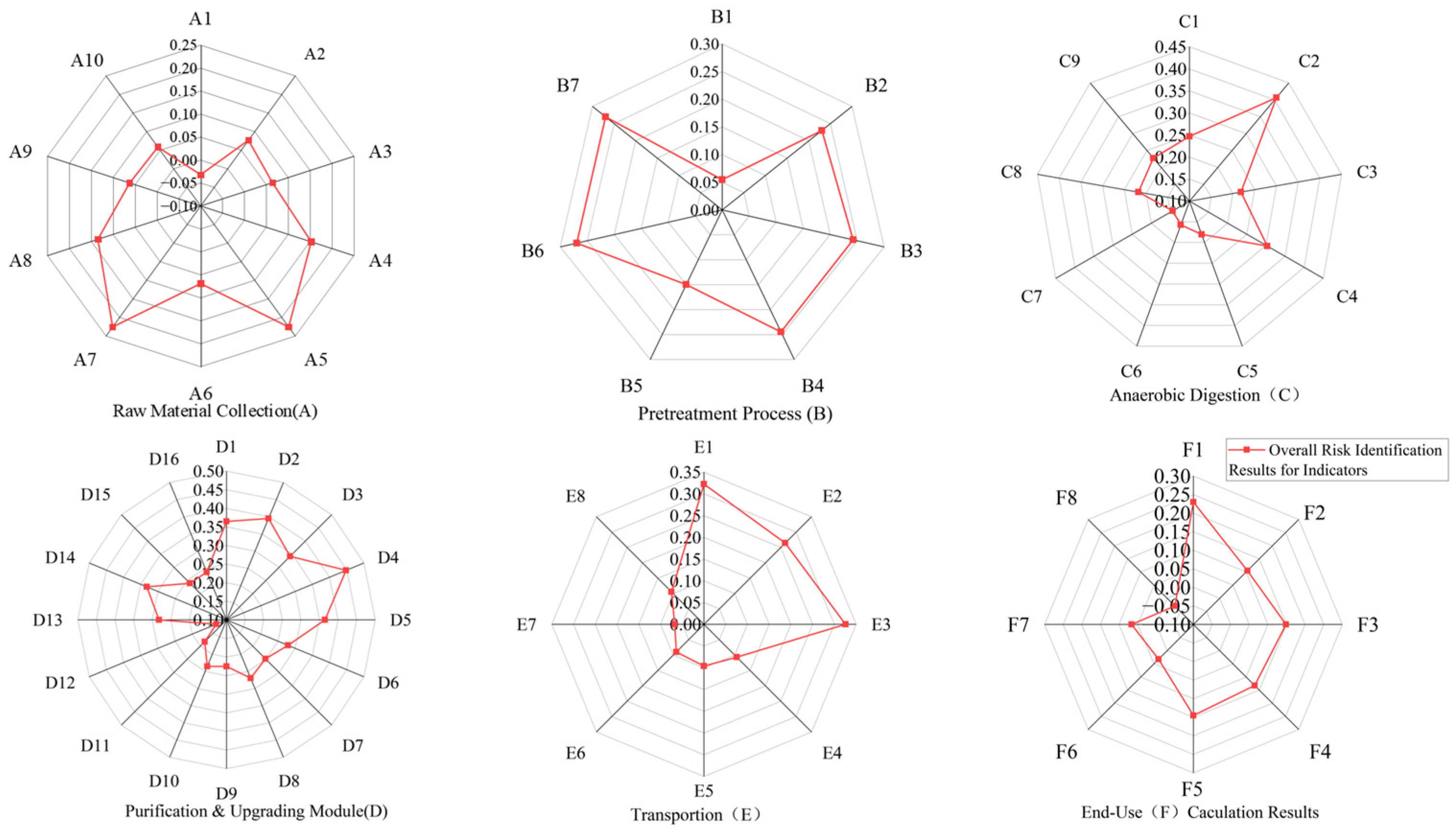

3.3. The Whole-Process, System-Wide Risk Identification

- (1)

- Overall, the top three highest risks are: D2—hypoxia caused by sulfur compound leakage (0.395), C2—fire caused by anaerobic fermentation process (0.406), and D4—combustible gas burning due to ignition sources (0.448).

- (2)

- From the perspective of work breakdown items, W41 (desulfurization operation) has the most risks and the highest risk values, followed by W31 (mechanical stirring), while W11 (manure collection) presents the lowest risk.

- (3)

- From the perspective of risk factor breakdown, R51 (unreasonable management organization) has the most risks and the highest risk values, followed by R21 (ignition sources). The lowest risks are R13 (struck by objects), R14 (falls and puncture wounds), R16 (frostbite), R32 (heavy metals), and R35 (presence of chemical toxicity).

- (4)

- From a comprehensive module perspective, both the anaerobic fermentation and purification and upgrading modules contain the most sub-risk items and have the highest risk values, warranting special attention.

- (1)

- In the entire W1 (raw material collection) process, overall, W111, W112, and W113 each have one severe risk point, while W131 has three risk points with relatively high risk values. This indicates that W131 (incineration of dead livestock) presents relatively more serious risks during the entire raw material treatment process.

- (2)

- In the W4 (purification and upgrading) process, there are the most risk factors, with 6 out of the top 10 risks belonging to W4. The highest-ranked risk is D4—combustion of flammable gas due to ignition sources (0.034), demonstrating that the purification and upgrading module contains the most risk points and has the highest risk values in the LMtB supply chain, requiring key supervision.

- (3)

- In the W3 (anaerobic fermentation) process, C2—fire caused by anaerobic fermentation process is the second highest risk point. W33 and W34 each have two types of highest-ranked risks.

- (4)

- Compressed gas tanker transportation (W51) and pipeline transportation (W52) each have one highest-ranked risk. The above processes require special attention from relevant departments.

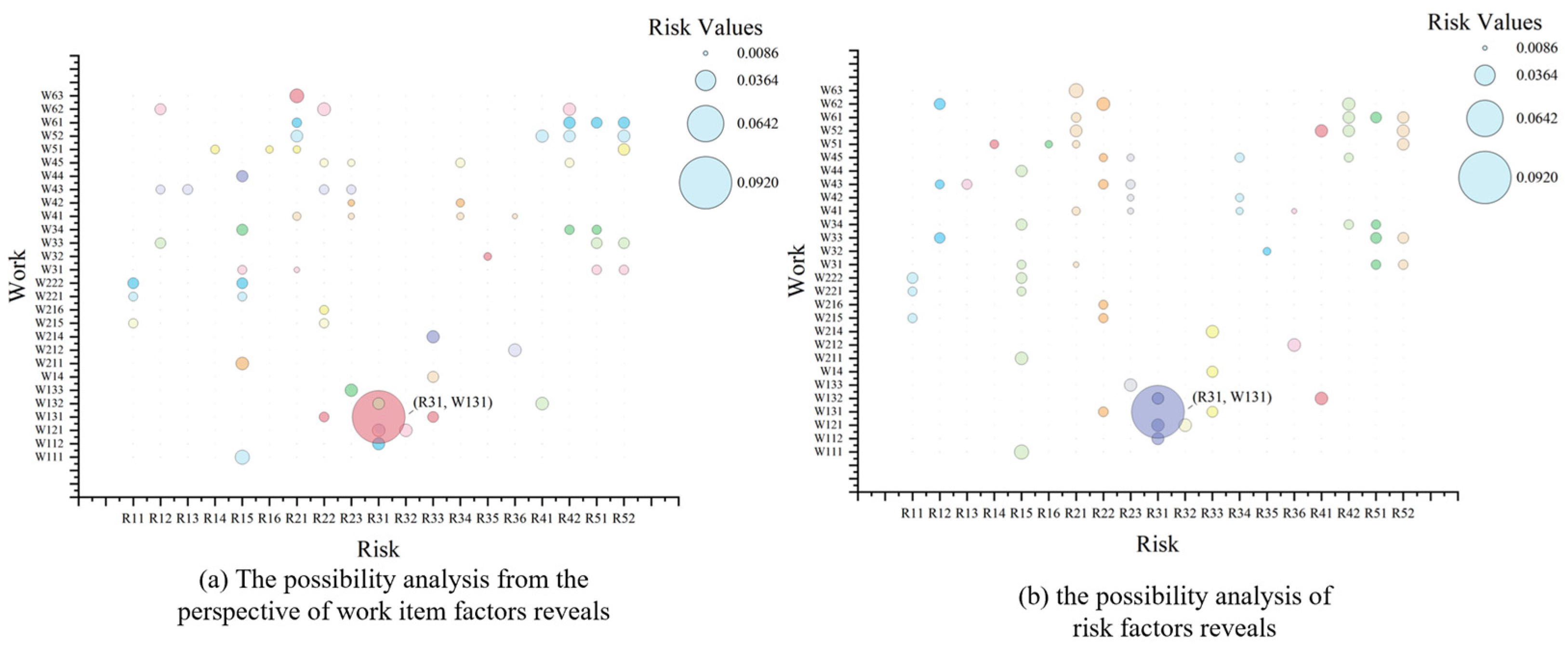

- (1)

- The two risk factors R15 (unreasonable management organization) and R21 (ignition sources) show the highest occurrence frequencies across all transportation processes, with 8 and 6 occurrences, respectively. This indicates that special attention should be paid to the rationality of management organization design, and strict monitoring should be implemented for ignition source control. These two risk factors require prioritized management by relevant departments.

- (2)

- The four risk factors R22 (improper operation), R23 (leakage), R42 (pipeline risks), and R52 (personnel management) demonstrate identical occurrence frequencies (5 times each), which are also relatively high. These risk categories warrant significant attention.

- (3)

- In conclusion, from the perspective of risk factor analysis, the following aspects require particular attention and control in the LMtB supply chain system: rational design of management organization, effective control of ignition sources, proper operational procedures, valve control to prevent leakage risks, safety-conscious pipeline design, and personnel management for operational supervision.

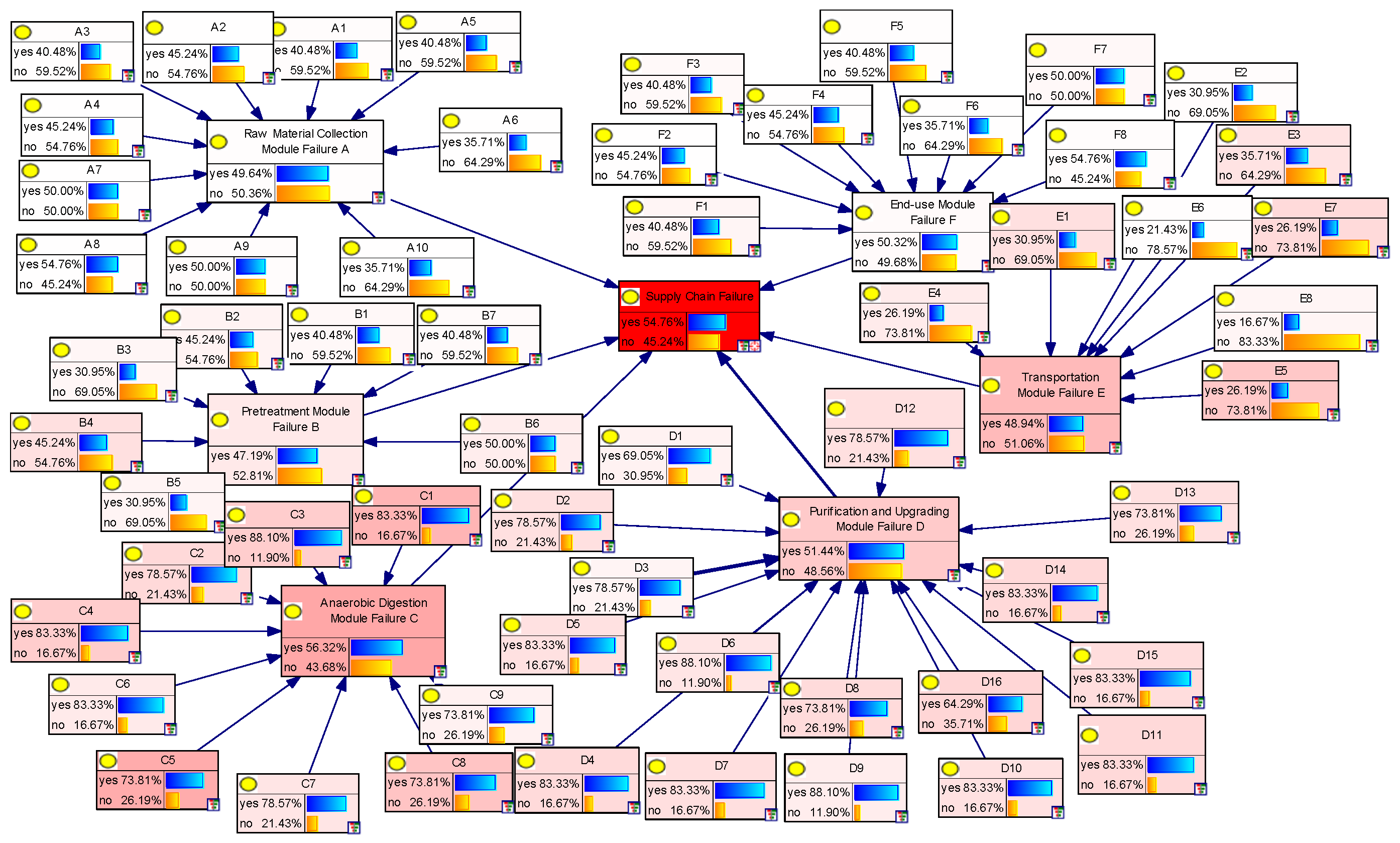

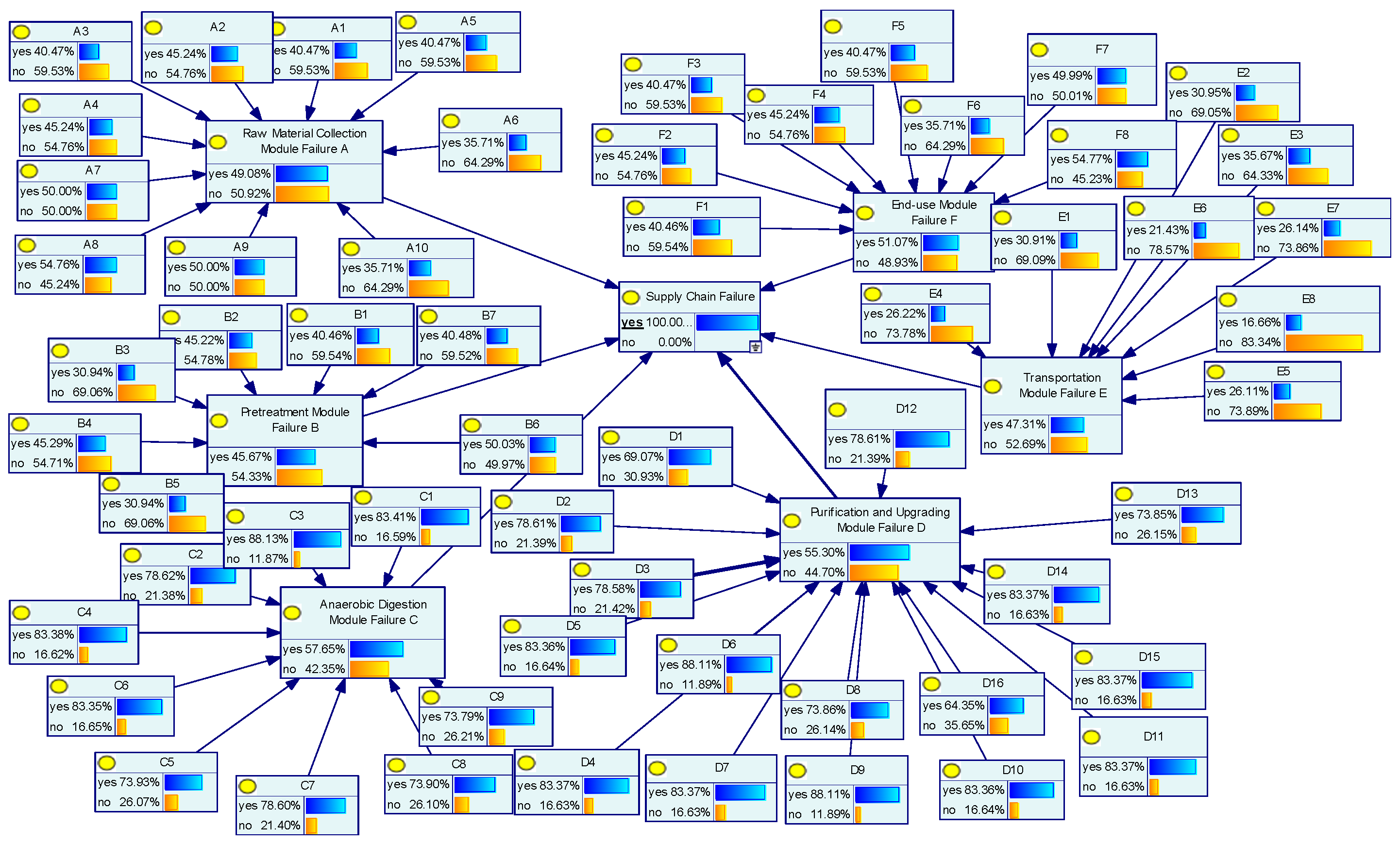

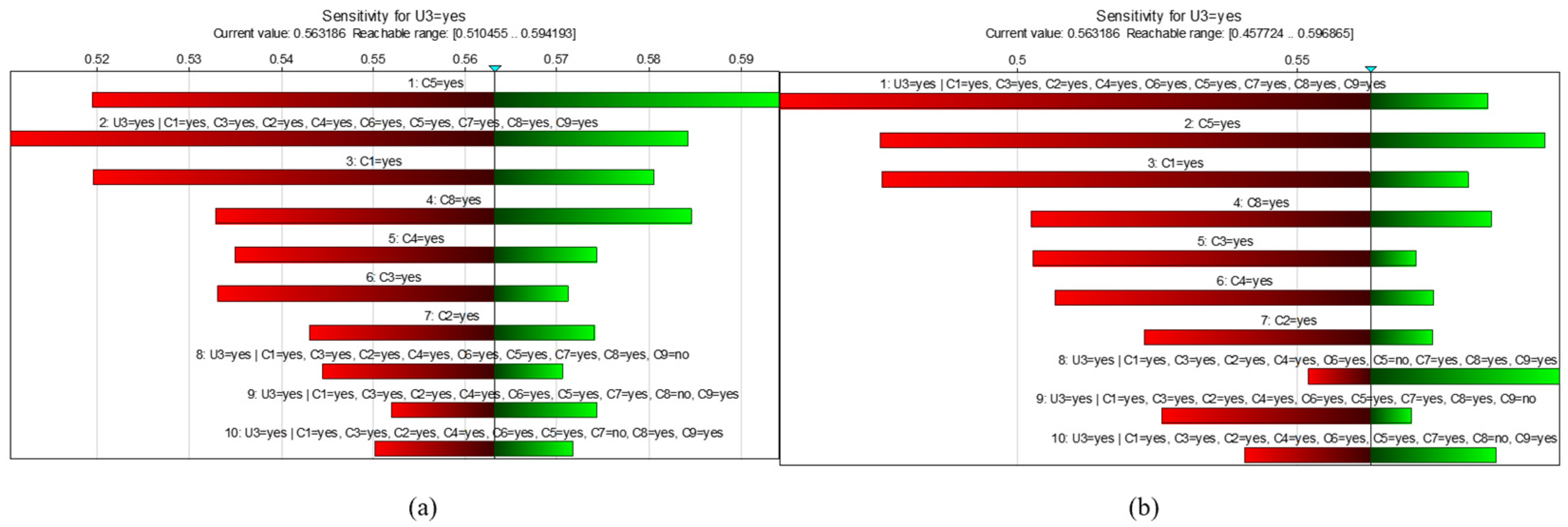

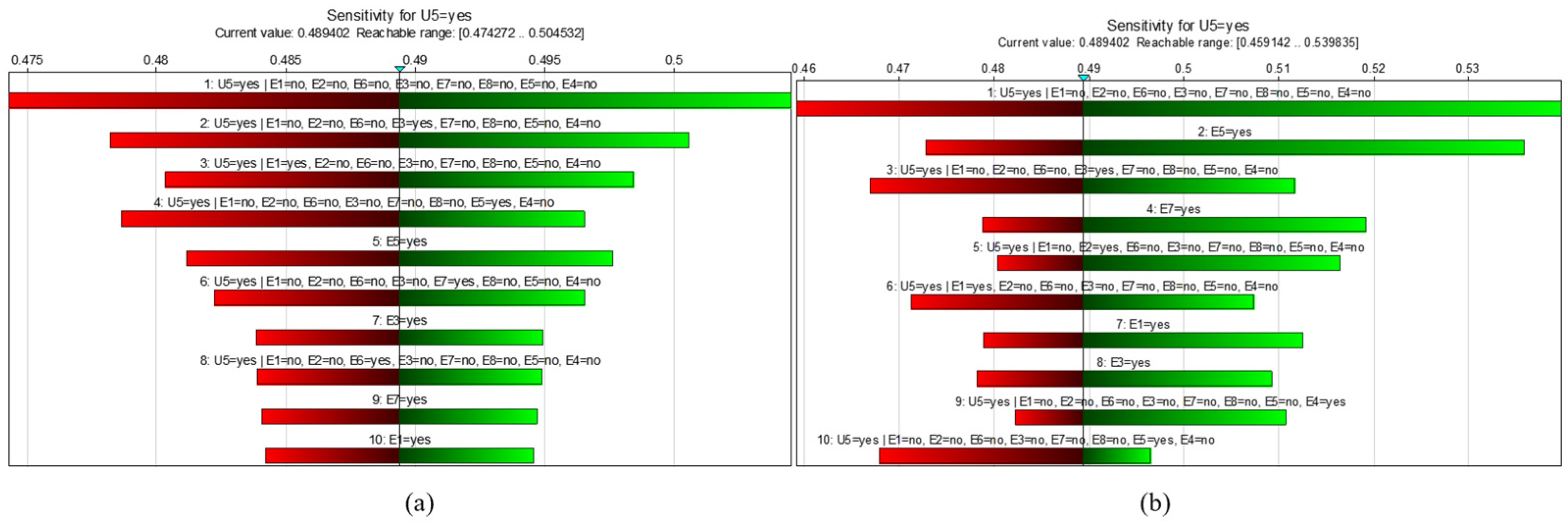

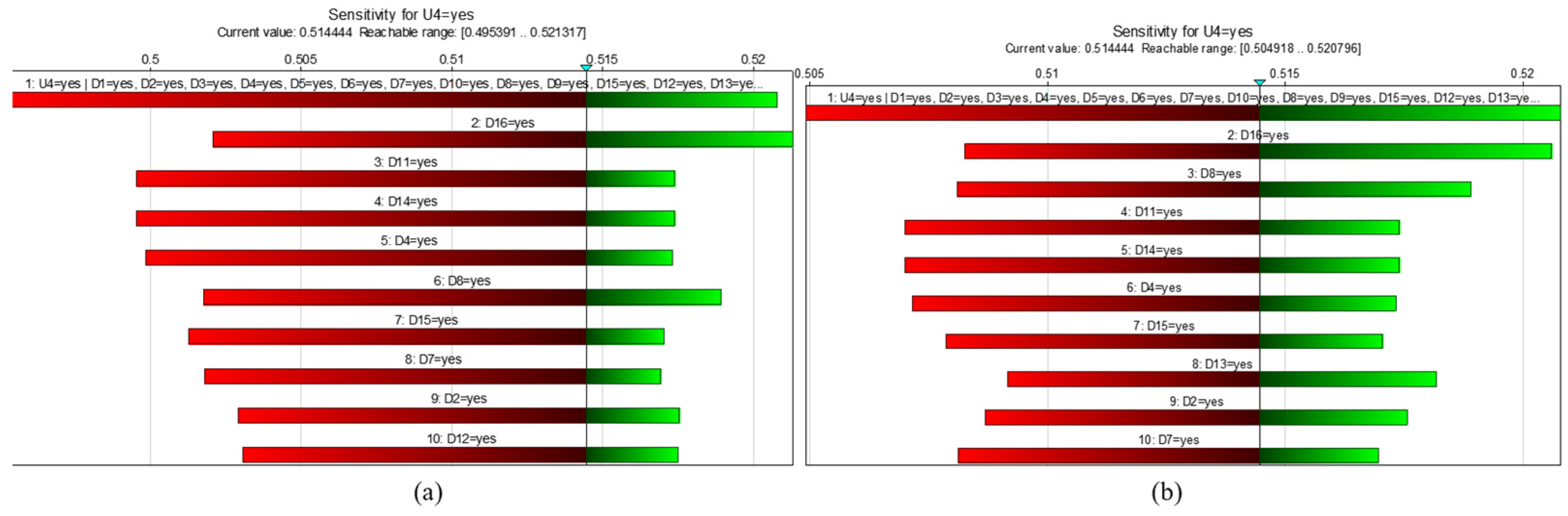

3.4. Bayesian Modeling Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, Z.; Chen, Z. Dual-Path Exploration of Anaerobic Biotechnology under Carbon Neutrality Goals: From Wastewater Methane Production to Systematic Utilization of Renewable Energy. Front. Environ. Sci. 2025, 13, 1613690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X. The Promotion of Anaerobic Digestion Technology Upgrades in Waste Stream Treatment Plants for Circular Economy in the Context of “Dual Carbon”: Global Status, Development Trend, and Future Challenges. Water 2024, 16, 3718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, V.S.; Parajuli, R.; Scott, E.; Canter, T.; Lim, T.T.; Popp, J.; Thoma, G. Dairy and Swine Manure Management—Challenges and Perspectives for Sustainable Treatment Technology. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 778, 146319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, N.; Anderson, A.; Johnston, C.R.; Rooney, D.W. Evaluating the Opportunity for Utilising Anaerobic Digestion and Pyrolysis of Livestock Manure and Grass Silage to Decarbonise Gas Infrastructure: A Northern Ireland Case Study. Renew. Energy 2022, 196, 343–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiland, P. Biogas Production: Current State and Perspectives. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 85, 849–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balussou, D.; Kleyböcker, A.; McKenna, R.; Möst, D.; Fichtner, W. An Economic Analysis of Three Operational Co-Digestion Biogas Plants in Germany. Waste Biomass Valoriz. 2012, 3, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, J.; Xue, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wu, W.; Jiang, H.; Cao, D. Agricultural Methane Emissions in China: Inventories, Driving Forces and Mitigation Strategies. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 13292–13303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Sommer, S.G.; Christensen, K.V. A review of the biogas industry in China. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 6073–6081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Gao, X. Biogas: Potential, challenges, and perspectives in a changing China. Biomass Bioenergy 2021, 150, 106127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, D.; Wang, L.; Pu, X.; Song, L.; Wang, Z.; Lei, Y.; Chen, Z.; Long, Y. Application and development of biogas technology for the treatment of waste in China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 70, 845–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhao, L.; Ren, C.; Wang, F. The progress and prospects of rural biogas production in China. Energy Policy 2012, 51, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghpour, A.; Afshar, R.K. Livestock Manure: From Waste to Resource in a Circular Economy. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 17, 101255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oehmichen, K.; Majer, S.; Thrän, D. Biomethane from Manure, Agricultural Residues and Biowaste—GHG Mitigation Potential from Residue-Based Biomethane in the European Transport Sector. Sustainability 2021, 13, 14007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafakheri, F.; Nasiri, F. Revenue Sharing Coordination in Reverse Logistics. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 59, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaderi, H.; Pishvaee, M.S.; Moini, A. Biomass Supply Chain Network Design: An Optimization-Oriented Review and Analysis. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 94, 972–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gital Durmaz, Y.; Bilgen, B. Multi-Objective Optimization of Sustainable Biomass Supply Chain Network Design. Appl. Energy 2020, 272, 115259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla-Rivera, A.; Paredes, M.G.; Güereca, L.P. A Systematic Review of the Sustainability Assessment of Bioenergy: The Case of Gaseous Biofuels. Biomass Bioenergy 2019, 125, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalkey, N.; Helmer, O. An Experimental Application of the DELPHI Method to the Use of Experts. Manag. Sci. 1963, 9, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyatt, N. Guidelines for Process Hazards Analysis (PHA, HAZOP), Hazards Identification, and Risk Analysis; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; pp. 154–196. [Google Scholar]

- Kletz, T.A. Hazop & Hazan: Identifying and Assessing Process Industry Hazards; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; pp. 162–178. [Google Scholar]

- Ferdous, R.; Khan, F.; Sadiq, R.; Amyotte, P.; Veitch, B. Fault and Event Tree Analyses for Process Systems Risk Analysis: Uncertainty Handling Formulations. Risk Anal. 2011, 31, 86–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoemaker, P.J.H. Scenario Planning: A Tool for Strategic Thinking. Sloan Manag. Rev. 1995, 36, 25–40. [Google Scholar]

- He, Z.; Guo, J.; Xu, J. On the Safety Risk Assessment of the Multimodal Transportation Network Based on the WBS-RBS and PFWA Operator. J. Saf. Environ. 2020, 20, 441–446. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Niu, D.; Shen, J.; Wang, H. A Cost Risk Assessment Framework for UHV AC Projects Based on WBS-RBS-FAHP-COWA-Matter-Element Extension. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2025, 20, 2075–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zhao, W.; Zhu, C.; Xiao, D. Risk Identification and Assessment of Hainan Expressway Maintenance Based on Coupling of WBS-RBS and Fault Tree Analysis. J. East China Jiaotong Univ. 2016, 33, 58–64. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Wei, Q.; Zhao, G.; Wang, J.; Yin, Y. Safety Risk Identification Method for Railway Construction in Complex and Dangerous Areas. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowski, A.S.; Mannan, M.S.; Bigoszewska, A. Fuzzy Logic for Process Safety Analysis. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2009, 22, 695–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Grossmann, I.E. A Review of Stochastic Programming Methods for Optimization of Process Systems under Uncertainty. Front. Chem. Eng. 2021, 2, 622241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. Decision Making with the Analytic Hierarchy Process. Int. J. Serv. Sci. 2008, 1, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, L. Research on the Application of TOPSIS Method in EPC Risk Assessment. J. Eng. Res. Rep. 2024, 26, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, F.; Wassick, J.M.; Grossmann, I.E. Risk Management for a Global Supply Chain Planning under Uncertainty: Models and Algorithms. AIChE J. 2009, 55, 931–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hongan, Z.; Sanyang, L.; Xiangrong, F. Method for Uncertain Multi-Attribute Decisionmaking with Preference Information in the Form of Interval Numbers Complementary Judgment Matrix. Syst. Eng. Electron. Technol. 2007, 18, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, D.; Olson, D.L. The Method of Grey Related Analysis to Multiple Attribute Decision Making Problems with Interval Numbers. Math. Comput. Modell. 2005, 42, 991–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, R.M.; Martínez, C. Interval Sorting. In Automata, Languages and Programming, 37th International Colloquium, ICALP 2010, Bordeaux, France, 6–10 July 2010; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 132–135. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Li, K.W.; Xu, J. A Mathematical Programming Approach to Multi-Attribute Decision Making with Interval-Valued Intuitionistic Fuzzy Assessment Information. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 12462–12469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Shuai, B.; Zhang, G. Improved WBS-RBS Based Identification of Risks in Railway Transportation of Dangerous Goods. China Saf. Sci. J. 2018, 28, 93–99. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X.; Ren, W.; Xu, H.; Zheng, S.; Wu, S. Mechanism-Based Fire Hazard Chain Risk Assessment for Roll-on/Roll-off Passenger Vessels Transporting Electric Vehicles: A Fault Tree–Fuzzy Bayesian Network Approach. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, R.; Cui, Y.; He, A.; Jiang, W. Analyzing the Risk Factors of Hazardous Chemical Road Transportation Accidents Based on Grounded Theory and a Bayesian Network. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, M.; Liu, M.; Zhao, J. A Possibility Evaluation Model for Road Transportation of Hazardous Chemicals Based on Bow-Tie Theory and Bayesian Model. Emerg. Manag. Sci. Technol. 2025, 5, e011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Wang, T.; Liu, T. Bayesian Network-Based Risk Analysis of Chemical Plant Explosion Accidents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Kong, L.; You, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y. Dynamic Risk Analysis for Oil and Gas Exploration Operations Based on HFACS Model and Bayesian Network. Pet. Sci. Technol. 2025, 43, 676–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Li, Z.; Han, X.; Duan, X. Supply Chain Network Resilience by Considering Disruption Propagation: Topological and Operational Perspectives. IEEE Syst. J. 2022, 16, 5305–5316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.; Yang, M. Risk Assessment of Hazmat Road Transportation Accidents before, during, and after the Accident Using Bayesian Network. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 190, 760–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. Exploring Supply Chain Network Resilience in the Presence of the Ripple Effect. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 228, 10769345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xue, X.; Yeoh, W.; Sun, X.; Qin, H. Risk Propagation Analysis of Domino Effect in Chemical Accident: An Integrated Approach with Data Mining and Bayesian Networks. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2025, 98, 105745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Wang, H.; Wang, M. Risk Assessment of Bauxite Maritime Logistics Based on Improved FMECA and Fuzzy Bayesian Network. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baryannis, G.; Dani, S.; Antoniou, G. Predicting Supply Chain Risks Using Machine Learning: The Trade-off between Performance and Interpretability. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019, 101, 993–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickens, C. Engineering Psychology and Human Performance; HarperCollins Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.J.; Chen, S.M. A New Method to Measure the Similarity between Fuzzy Numbers. In Proceedings of the 10th IEEE International Conference on Fuzzy Systems, Melbourne, Australia, 2–5 December 2001; pp. 1123–1126. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, P.-D. Method for Multiple Attribute Decision-Making under Risk with Interval Numbers. Int. J. Fuzzy Syst. 2010, 12, 237–242. [Google Scholar]

- Pearl, J. Probabilistic Reasoning in Intelligent Systems: Networks of Plausible Inference; Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1991; pp. 79–94. [Google Scholar]

| Fuzzy Set | Cut Set |

|---|---|

| fVL = (0, 0, 0.1, 0.2) | fλVL = [0.1λ + 0, −0.1λ + 0.2] |

| fL = (0.1, 0.2, 0.3) | fλL = [0.1λ + 0.1, −0.1λ + 0.2] |

| fFL = (0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5) | fλFL = [0.1λ + 0.2, −0.1λ + 0.5] |

| fM = (0.4, 0.5, 0.6) | fλM = [0.1λ + 0.4, −0.1λ + 0.6] |

| fFH = (0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8) | fλFH = [0.1λ + 0.5, −0.1λ + 0.8] |

| fH = (0.7, 0.8, 0.9) | fλH = [0.1λ + 0.7, −0.1λ + 0.9] |

| fVH = (0.8, 0.9, 1.0) | fλVH = [0.1λ + 0.8, −0.1λ + 1.0] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Jia, X.; Wang, F. Bayesian Network-Based Failure Risk Assessment and Inference Modeling for Biomethane Supply Chain. Safety 2026, 12, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety12010009

Wang Y, Wang S, Jia X, Wang F. Bayesian Network-Based Failure Risk Assessment and Inference Modeling for Biomethane Supply Chain. Safety. 2026; 12(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety12010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yue, Siqi Wang, Xiaoping Jia, and Fang Wang. 2026. "Bayesian Network-Based Failure Risk Assessment and Inference Modeling for Biomethane Supply Chain" Safety 12, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety12010009

APA StyleWang, Y., Wang, S., Jia, X., & Wang, F. (2026). Bayesian Network-Based Failure Risk Assessment and Inference Modeling for Biomethane Supply Chain. Safety, 12(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety12010009