1. Introduction

The relationship between organizational culture and organizational performance has been thought to explain why one company succeeds where another fails within an industry. Safety culture was first used in reference to the Chernobyl nuclear accident to describe the “characteristics and attitudes in organizations and individuals” related to workplace safety (IAEC, 1991) [

1]. Recently, Al-Mekhlafi et al. (2025) analyzed 7058 papers on the topic of safety culture published between 1978 and 2023 and concluded that critical areas such as the transportation industry were underrepresented and could benefit from additional studies to assist in improving public safety [

2]. Other research has suggested that organizational leaders might improve safety performance by utilizing transformational leadership practices (Frazier, 2018) [

3]. Additionally, Casey (2017) reported on several studies that linked the safety climate to occupational safety performance and concluded that “safety climate is firmly established as an organizational antecedent of safety performance” [

4].

The US Department of Transportation Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) also determined that safety culture plays a key role in accident prevention [

5]. In addition, Canada’s Transportation Safety Board (TSB, 2022) identified a number of factors that likely contributed to the catastrophic Lac-Mégantic derailment that resulted in a significant loss of life, noting that the company that owned the railroad “was a company with a weak safety culture that did not have a functioning safety management system to manage risks” [

6].

Schein (2004) postulated that an organization’s culture is its pattern of shared assumptions, values, norms, and rules of behavior [

7]. He also wrote that leadership is the source of those beliefs and values. A leader’s assumptions, beliefs, and values gradually come to be the shared assumptions, beliefs, and values of an organization. Consequently, leaders and their leadership styles are essential to the formation, maintenance, and transformation of organizational cultures. Bass and Riggio (2006) discussed both transformational and transactional leadership styles and their implications for organizational behavior; implications for safety culture were implied but not reviewed [

8].

Reason (1998) argued that the safety culture develops in response to local circumstances, events, and conditions, the character of the leadership, and the mood of the workforce [

9]. According to Reason, the safety culture affects all aspects of an organization and influences the occurrence of accidents and injuries. In fact, only a positive safety culture can prevent the conditions and circumstances that lead to lapses, near misses, and accidents.

Sherry (2018) developed the Safety Culture Scale (SCS) to measure safety culture, normed on a sample of employees from a large public transportation agency (

n = 1909) [

10]. The validity of the measure was confirmed, as the scale significantly differentiated (

p < 0.05) between people who had been involved in accidents and safety violations and those who had not. A follow-up study with a large regional transportation company demonstrated significant differences in safety culture and attitudes between key departments in the organization.

A meta-analysis by Clarke (2013) investigated transformational and transactional leadership in relation to safety behaviors [

11]. After reviewing over 800 papers, 103 were found to be empirical, and a final 32 studies (37 independent samples) were found that measured leadership (

n = 24,363) in relation to safety-related variables and contained sufficient data for analysis. The strongest relationships were found between a transformational style for both perceived safety climate (ρ = 0.48,

p < 0.05) and safety participation (ρ = 0.44,

p < 0.05). A significant (but smaller) effect size was found between transformational leadership and safety compliance (ρ = 0.31,

p < 0.05). There were also significant relationships between active transactional leadership and both safety compliance (ρ = 0.41,

p < 0.05) and safety participation (ρ = 0.36,

p < 0.05). Safety compliance was more strongly related to active transactional leadership (ρ = 0.41) than transformational leadership (ρ = 0.31), while safety participation was more strongly related to transformational (ρ = 0.44) than active transactional leadership (ρ = 0.36).

Previous research provides conflicting evidence on which type of leadership behavior is most effective in the workplace. One review (Nasim et al., 2023) suggested that many different styles of leadership are positively correlated with a good safety culture [

12]. Further research is required to determine which style is most useful in different industries. Based on their review of 24 empirical studies, the empowering leadership style (r = 0.60) emerged as the most influential across all organizations and in high-risk organizations, followed by the transformational leadership style. Transformational leadership has been studied most frequently in the healthcare industry, whereas empowering leadership has been studied more in the manufacturing sector.

A review by Lundell and Marcham (2018) concluded that both transformational and transactional leadership styles, as well as both autocratic and democratic styles, have a positive impact on safety culture [

13]. However, practical guidance and an unequivocal best choice from the transformational, transactional, autocratic, or democratic styles is not immediately apparent. After reviewing over 100 safety-related publications, Sanker and Anandh (2024) concluded that transformational leadership was the most impactful style for improving safety outcomes in the construction industry [

14]. Pai et al. (2024) also discussed the importance of transformational and transactional leadership in the food safety industry [

15]. The negative effects of a laissez-faire style and management by exception were seen as the least desirable approaches. Payne et al. (2025) also concluded that multiple leadership styles contribute to safety behaviors in different ways across different work scenarios, but did not determine the optimal style for particular settings [

16].

Few studies have examined safety culture development, and the leadership styles required to achieve this, in the rail-transportation industry, which is generally thought to be a high-risk setting. A study by Al-Mekhlafi et al. (2022) concluded that work schedules and safety culture influenced truck driver performance [

17]. Furthermore, according to Grinerud et al. (2021) “no one has specifically addressed how leadership strategies support and/or constrain safety culture in road transport organizations.” Consequently, further research is needed to clarify the role of leadership and leadership styles in developing safety culture in transportation industry settings [

18].

Although research has examined the relationship between leadership and safety (Clarke, 2013) [

11], inconclusive results have been obtained regarding how different leadership styles influence workplace safety and which styles are most associated with good workplace safety (Donovan et al., 2016) [

19]. This indicates that further investigation into the mechanisms by which leadership affects safety performance is warranted (Mirza & Isha, 2017; Pilbeam et al., 2016), as is clarification of which styles of leadership behavior promote an effective safety culture [

20,

21].

In addition to transformational and transactional leadership, Goleman’s (2019) description of leadership styles provides more specificity in terms of the operational environment [

22]. The present study examines the relative contribution of authoritative and democratic leadership and their impact on the perceived effectiveness of the safety culture.

Based on a review of the literature, it is apparent that little has been written about the type of leadership style that would be effective in the rail transportation industry. Transformational leadership has been studied, but research provides little guidance for practitioners. The rail transportation industry work environment is considered to be high risk—requiring detailed safety protocols, clear procedures for tasks and emergencies, and the use of specialized equipment. The present study is intended to shed more light on the types of leadership styles that could be useful in promoting an effective safety culture in the rail transportation industry. It is hypothesized that a strong safety culture will be one that uses a more directive approach, as opposed to a participatory or democratic one.

2. Methods

Using a naturalistic field study design, employees at a midsized rail transportation company in the Eastern United States participated in a study investigating their perceptions of the organizational safety culture by completing questionnaires. Employees completed the Safety Culture Survey (SCS) and a modified set of items from the Management Style Inventory (MSQ). Paper-and-pencil surveys were administered in person over a one-week period to employees reporting for work at designated crew areas at the start and end of their work shifts.

The railway company studied has two major lines serving a major metropolitan area in the Eastern United States. The service extends over a roughly 100-mile area operating along 89 miles of track. The company operates an average of 32 trains from 19 stations and carries, on average, 12,000 passengers daily.

The total number of employees working at the time of the study was less than 100. Operating personnel (engineers, conductors, and maintenance) are subcontracted through a third-party vendor. A total of 17 employees were designated management, and the remaining were operating and support personnel involved in areas such as safety, engineering, and security.

2.1. Procedure

The study design and consent form was approved by the university ethics committee. All scales described above were combined into one questionnaire packet, which was made available and distributed to participants in a paper format at their workplace during the data collection period.

Study participants were employees of the company who arrived for work during the one-week data collection period. Employees arrived for work at three designated crew stations and two mechanical shops on the system. Researchers distributed informed consent materials and administered the paper-and-pencil survey to employees as they were beginning or ending their shifts. No incentives were provided. Approximately 119 surveys were administered; of the collected questionnaires, 65 were suitable for inclusion in the analysis.

2.2. Instruments

The survey packet administered to employees consisted of three parts included in the Safety Culture Survey (SCS) (Sherry 2018): The Transportation Leadership Style Survey (TLS), the Various Management Practices (VMP) Scale, and the Safety Culture Effectiveness Scale (SCE).

Safety Culture Survey (SCS). The SCS was developed by Sherry (2018); it has ten scales assessing components of safety culture. The scales and structure were determined via a procedure using expert judgment and focus groups to identify viable items, followed by principal component factor analysis to reduce the number of items and develop scales with acceptable internal consistency. Ten scales were identified: Management Commitment—Immediate Supervisor; Management Commitment—Senior Managers; Peer Commitment; Education Focus; Safety knowledge; Safety Rewards; Accountability; Safety Practices; Personal Responsibility; and Safety vs. Productivity. Subsequent analyses and investigations verified the relationship between the factors and safety performance in several settings. Reliability estimates of the scales in the original validation study ranged from α = 0.52 to 0.83, demonstrating acceptable levels of reliability. The scales in the SCS have been shown to measure various aspects of safety culture.

Transportation Leadership Style (TLS). The Transportation Leadership Style inventory was developed by using items adapted from the Management Style Inventory (Hay McBerr (1985) and Goleman (2019)) [

22,

23]. Items were adapted from the Authoritative and Democratic style scales, as they were deemed most appropriate to the circumstances in the transportation industry context. Items were rated using a five-point Likert-style format ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. The items were administered alongside the Safety Culture Survey (SCS) to assess leadership style. Reliability estimates using Cronbach’s alpha were found to be α = 0.844 and α = 0.859 for the Authoritative and Democratic scales, respectively.

Various Management Practices (VMP) Scale. Management practices were input into the Various Management Practices (VMP) Scale, which consists of safety briefings, taking shortcuts, encouraging quick production, and others. These were labeled with information typical of supervisory practices but not consistent with a particular leadership or management style.

Safety Culture Effectiveness (SCE). A single-item measure of the perceived effectiveness of the safety culture was used as an outcome measure. The item wording “The safety culture here is effective at promoting safety” utilized a five-point Likert response scale ranging from “Strongly Disagree” to “Strongly Agree.”

2.3. Data Analysis

Pearson correlation coefficients were computed and regression analyses conducted between leadership style scales and the Safety Culture Effectiveness ratings to determine the magnitude of the relationship between the leadership style and safety culture. In addition, to further illustrate relationships between leadership style and SCE, the scale scores were reduced to dichotomized values and odds ratios were computed.

4. Discussion

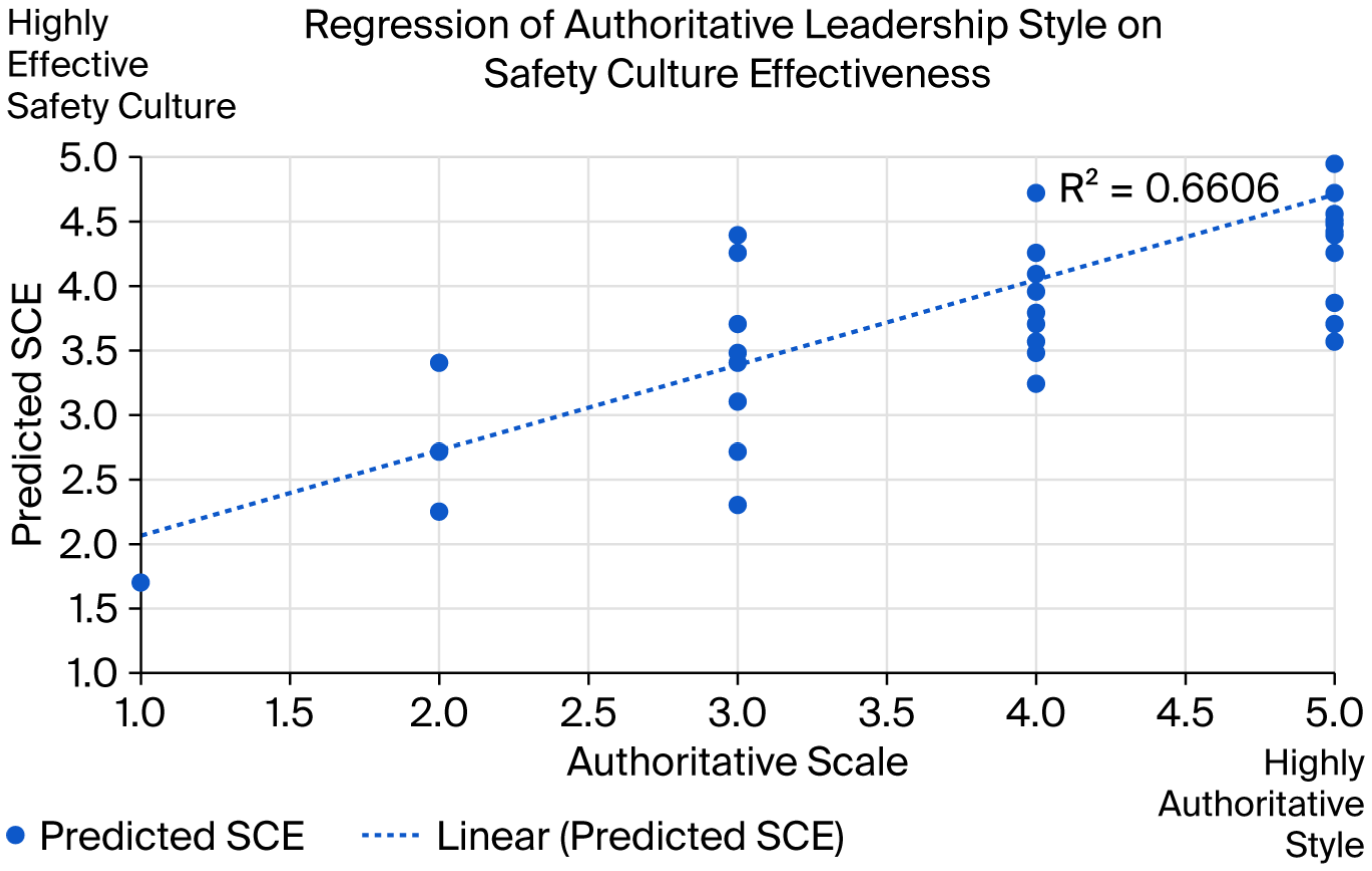

Employees of a midsized rail transportation company in the Eastern US completed a survey assessing leadership behaviors and safety culture. The survey included measures of safety culture, leadership behaviors, and an overall rating of Safety Culture Effectiveness (SCE). The results of correlational analyses demonstrated strong associations between leadership practices and behaviors and employees’ perceptions of an effective organizational safety culture. Strong senior management commitment and a focus on educating employees to behave in accordance with safety issues using predetermined procedures were significantly associated with a perceived effective safety culture. In addition, authoritative leadership behaviors were highly positively correlated with effectiveness, while democratic leadership behaviors were less strongly correlated. Regression analyses, which examined the combined contribution of the Authoritative scale items onto the perception of SCE, revealed that the Authoritative leadership style was significantly correlated with SCE and the Democratic style less so. Moreover, the odds of the safety culture being perceived as effective were increased if authoritative rather than democratic leadership behaviors were exhibited. The results of the present study are both expected and unexpected considering the previous literature.

4.1. Practical Implications for Management

A growing body of research has pointed to the importance of managerial leadership as a key factor influencing safety and safety performance. Analysis of the responses to the measures in the present study indicates that the data generated by the SCS was able to demonstrate that the perceived effectiveness of the SC was in fact promoted by the perception that both senior management and immediate management (i.e., supervisors) were committed to safety. This implies that the activities and behaviors engaged in by the supervisors and senior leaders convey to the employees that the company is committed to safety and that safety is indeed important.

From a practical perspective, a leader that is focused on education and training and provides support to employees is highly likely to increase in the perception of safety culture effectiveness. To a lesser extent, as evidenced by the smaller magnitude of the correlation coefficients, a focus on accountability or discipline or providing rewards for people engaged in safe behaviors, such as commendations or other mechanisms, were also associated with the perceived effectiveness of the safety culture. Finaly, the positive correlations between SCS scales and SCE ratings indicate that individual or personal characteristics and the perceived commitment of peers and coworkers was even less strongly associated with the perceived effectiveness of the safety culture. In all, the activities of the leaders (i.e., managers and supervisors) were significantly correlated with the perception of effectiveness; other influence factors were less potent. Together, these results suggest that leadership behaviors can indeed have a very strong influence on the perception of safety culture effectiveness.

In terms of improving safety culture in the workplace, our results suggest that the strongest relationship between safety culture effectiveness and leadership is promoted by leader and supervisor behaviors focused on monitoring and training, and providing detailed instructions and discipline. The item “no patience for rule breakers” has some association, but the magnitude of the relationship was not as strong as that for other aspects of supervisor behavior. Taken together, behaviors associated with an authoritative style seem to have the largest effect on promoting an effective safety culture. Leaders and supervisors who use an authoritative approach, characterized by active monitoring and training, may be attempting to inspire or instill a culture of safety, which is a more “transformational” approach. In other words, leading by doing may have a more powerful effect, at least in the transportation industry.

This can also be observed when looking at the results for the democratic style of leadership and its impact on perceived effectiveness. To some extent, coming to a consensus on how to be safe is of course a reasonable approach. However, when it comes to conveying and producing the desired effect, consensus-seeking behavior may not be the most powerful leadership style in an operational environment. Basically, in work environments where employees “must wear their seat belts” or “must wear hard hats”, there is no place for seeking consensus. Therefore, while the general idea of consensus-seeking makes sense with respect to general goals, specific safe practices actually need to be identified, taught, monitored, and complied with.

Also noteworthy are the findings that respondents were 28 times more likely to perceive the safety culture as effective if supervisors engaged in leadership behaviors involving “monitoring compliance” with safety procedures, including providing training, education, and detailed instructions on how to perform work tasks. It appears that day-to-day leadership behaviors categorized as authoritative in Goleman’s (2019) taxonomy of leadership styles are most likely to lead to an effective safety culture.

Managers and supervisors in the rail transportation industry can be guided by the results of his study and note that an active and authoritative approach that provides guidance, instruction, and monitoring of safety practices and procedures is likely to result in the perception, and hopefully development, of an effective safety culture. Less emphasis on discipline, taking shortcuts, occasionally making exceptions, or bending the rules will also likely lead to a more effective safety culture.

4.2. Contribution to Safety Culture Research

In comparison with previous studies, these results provide more information regarding the type of leadership style and behavior required to achieve an effective safety culture. Previous studies have noted the strong relationship between transformational leadership and developing an effective safety culture. The present study does not contradict this finding, rather, it provides more clarity and specificity with respect to what leadership styles and behaviors are associated with particular organizational behavior outcomes. Put another way, this is not to say that transformational leadership is ineffective but rather, in a high-risk environment like rail transportation, the inspirational and value-focused aspects of transformation leadership may not translate into perceived effectiveness ratings. In transportation occupations and workplaces, an emphasis on strict adherence to procedures and processes, as opposed to more attitudinal and participatory activities, is likely to be better achieved using specific authoritative styles that prescribe certain procedures and actions.

Muchiri et al. (2019) argued that “transformational leadership may not be adequate to enhance employee safety behavior” and focused on the role of empowering leadership behaviors and their influence on workplace safety [

25]. They defined empowering leadership as the development of employee self-management and self-leadership skills, as well as involvement in decision-making regarding health and safety. Empowering leaders also encourages employees to take responsibility for their own safety. Similarly, democratic leadership styles emphasize a collaborative approach involving followers in the decision-making process and a greater sense of ownership and responsibility among employees.

Interestingly, the results of this study suggest that authoritative and directive leadership styles are more likely to be associated with an effective safety culture. The results suggest that authoritative leadership is more strongly associated with an effective safety culture, compared to democratic leadership behavior.

The findings of this study contribute to the literature by more precisely specifying the types of leadership styles and behaviors that are most helpful in improving safety culture in the workplace. As other studies have shown, transformational leadership has a positive relationship with promoting an effective safety culture. The present research extends the understanding that a transformational style may not be as strong as described in other reviews of the literature (i.e., Clarke, 2013; Nasim et al., 2023) [

11,

12]. In fact, in a high-risk work environment, a focus on directive or authoritative behaviors may be necessary to achieve the most effective safety culture.

This study is limited by the self-report nature of the data collection method. In addition, the range of leadership behaviors and styles that exist in the workplace are numerous and varied, so all cannot be covered. Future research could benefit from obtaining measures from a broader range of leadership behaviors. A study by Kim & Gausdal (2020) examining various leadership tactics in addition to style showed promising results [

26]. Furthermore, independent assessments and measures of safety culture effectiveness, such as accident rate data, and independent ratings and measures of leadership behaviors could provide better overall validation of the effectiveness of the safety culture. Our findings are also limited to the railroad environment and not necessarily generalizable to other settings.

5. Conclusions

The present study examined employees’ perception of the relationship between supervisory leadership style and workplace safety culture in a midsized regional commuter railroad serving a metropolitan area in the Eastern United States. A representative sample of almost two-thirds of the company’s employees completed a survey examining leadership styles and practices related to effective safety culture.

The main findings revealed that managerial leadership style is significantly related to the perception of the effectiveness (and most likely the development) of the workplace safety culture. More specifically, an authoritative leadership style, characterized by monitoring and instructing employees on the required safety practices, was more strongly associated with high ratings of safety culture effectiveness than a democratic leadership style that encouraged consensus among employees. The findings also indicated that the probability of perceiving an effective safety culture was twenty-eight times more likely when supervisors were seen as monitoring and instructing, compared to not using those approaches. Furthermore, the leadership activities of seeking consensus (OR = 16), taking shortcuts (OR = 7.20), or bending the rules (OR = 0.26) were associated with much lower probabilities of producing an effective safety culture.

Based on the present findings, leaders seeking to develop a strong safety culture would do well to engage in behaviors involving “monitoring compliance” with safety procedures, providing training, education, and detailed instructions on how to perform work tasks, and disciplining employees for non-compliance. Seeking consensus with employees should be used judiciously, and possibly less frequently, with respect to safety-related decisions. A more democratic style of leadership has its place but probably should not be used as the main approach to developing a strong safety culture. Lastly, the results suggest that leaders should avoid placing productivity or speed ahead of safety and that taking shortcuts or bending the rules could negatively impact the development of an effective safety culture.

This study also builds upon previous research that identified transformational leadership as an important contributor to the development of safety culture. It does this by more explicitly specifying the types of leadership styles and behaviors that may be the most effective. Future research is needed to expand the assessment to other, non-railroad settings to further identify the types of leadership style or behavior needed to promote an effective safety culture in such settings.