Disclosures of Occupational Health and Safety Performance Indicators: A Perspective from South African Listed Companies

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. OHSMS, Performance Indicators and Corporate Reporting Behaviour

1.1.1. Accidents and Incident Reporting

1.1.2. Health and Safety Performance Measurement and Disclosures

1.1.3. Mine Health and Safety Council (MHSC) Milestone Targets

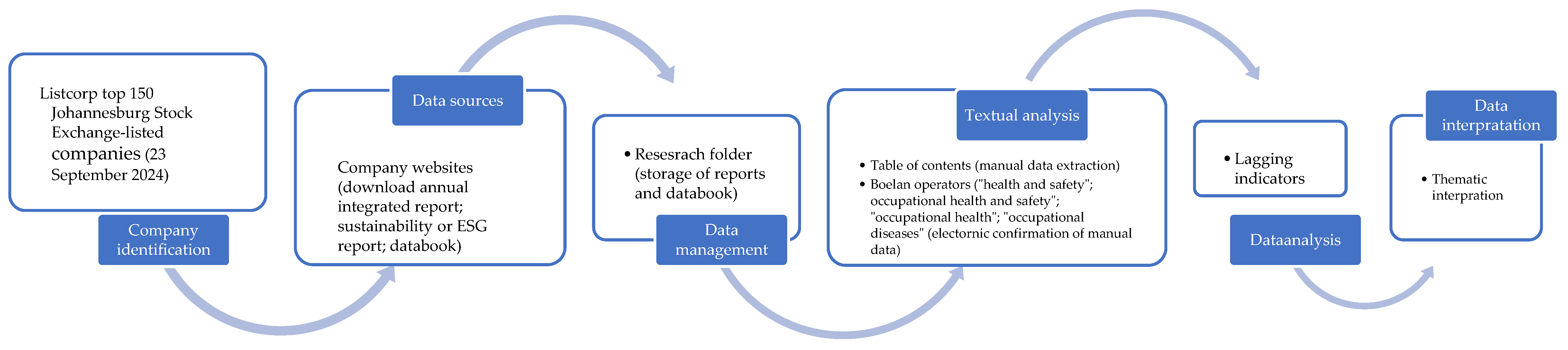

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Report Access, Data Extraction, Management and Analysis

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion of Reports

Inclusion and Exclusion of Leading Indicators

3. Results

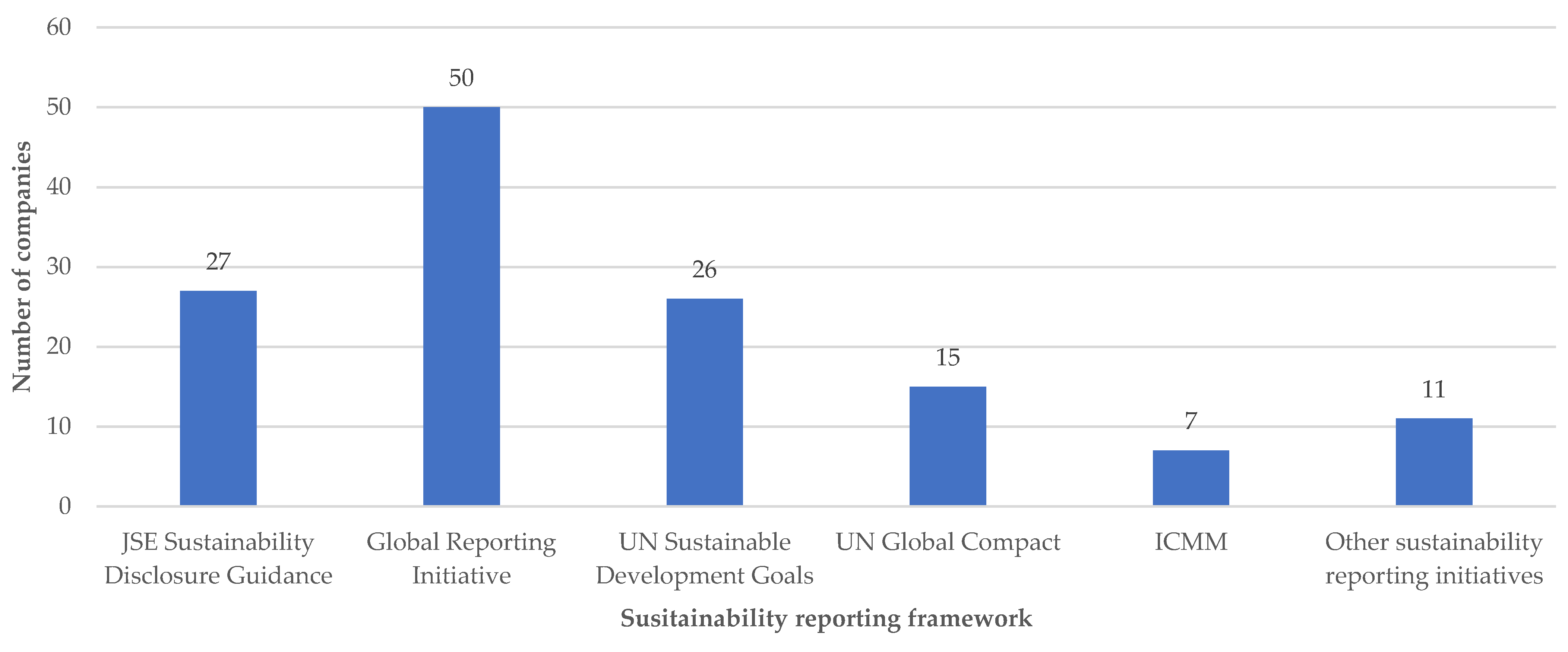

3.1. Overview of OHS Performance Reporting

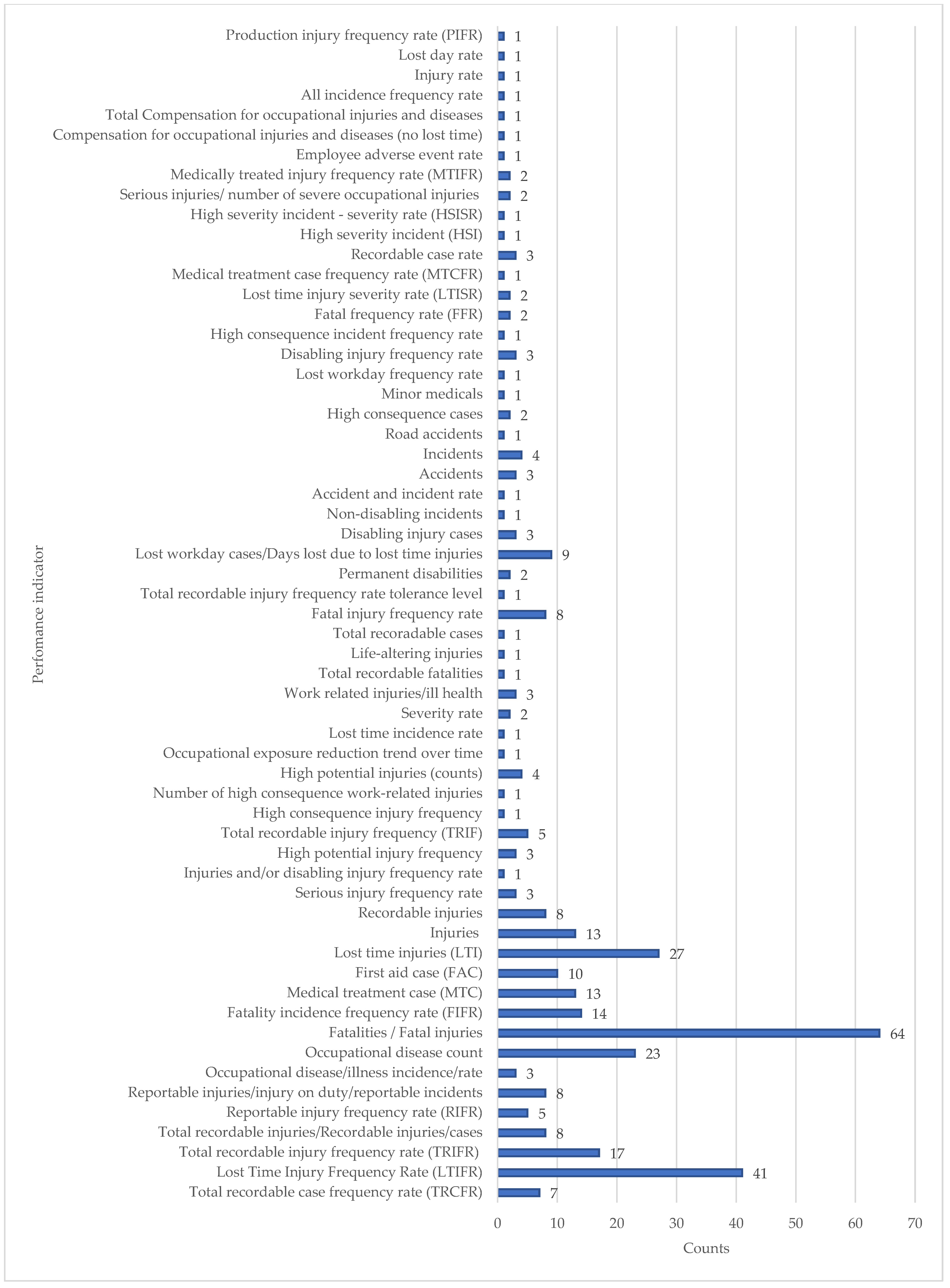

3.2. Overview of Reported Lagging Indicators

3.3. Sectoral Overview of Lagging Indicators Reported

3.4. Single Coding and Risk of Bias

4. Discussion

4.1. Overview of Performance Reporting

4.2. Overview of Performance Indicators

4.3. Implications and Recommendations

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OHSMS | Occupational health and safety management system |

| JSE | Johannesburg Stock Exchange |

| ISO | International Standardization Organization |

| OD | Occupational disease |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| MDPR | Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development |

| ICMM | International Council on Mining and Metals |

| ESG | Environmental Social and Governance |

| GRI | Global Reporting Initiative |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

| UNGC | United Nations Global Compact |

| KPI | Key performance indicator |

| MHSC | Mine Health Safety Council |

| LTI | Lost time injury |

| ICB | Industry Classification Benchmark |

| LTIFR | Lost time injury frequency rate |

| TRIFR | Total reportable injury frequency rate |

| FIFR | Fatal injury frequency rate |

| MTC | Medical treatment case |

| FAC | First aid case |

| IOD | Injury on duty |

| HSC | Health and Safety Commission |

| HSI | High severity incident |

| HSISR | High severity incident severity rate |

| LTISR | Lost time injury severity rate |

| FFR | Fatal frequency rate |

| MTIFR | Medically treated injury frequency rate |

| RIFR | Reportable injury frequency rate |

| TRCFR | Total recordable case frequency rate |

| RIDDOR | Reporting of Injuries, Diseases and Dangerous Occurrences Regulations |

References

- Mine Health and Safety Act. 1996. Available online: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/act29of1996s.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2017).

- Occupational Health and Safety Act and Regulations (85 of 1993). Available online: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/act85of1993.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2018).

- Health and Safety at Work Act. 1974. Available online: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1974/37/contents (accessed on 4 May 2020).

- The Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations. 1999. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/1999/3242/contents/made (accessed on 26 July 2020).

- Haas, E.J.; Yorio, P. Exploring the state of health and safety management system performance measurement in mining organizations. Saf. Sci. 2016, 83, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SANS 45001:2018; Occupational Health and Safety Management Systems—Requirements with Guidance for Use. Standards South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2018.

- International Council on Mining & Metals. Overview of Leading Indicators for Occupational Health and Safety in Mining: International Council on Mining & Metals. 2012. Available online: https://www.icmm.com/website/publications/pdfs/health-and-safety/2012/guidance_indicators-ohs.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Podgórski, D. Measuring operational performance of OSH management system—A demonstration of AHP-based selection of leading key performance indicators. Saf. Sci. 2015, 73, 146–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. Employer-Reported Workplace Injuries and Illnesses, 1995–2015. Available online: http://www.bls.gov/iif/oshwc/osh/os/osnr0021.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2016).

- Health and Safety Executive. Noise Induced Hearing Loss in Great Britain. 2025. Available online: http://www.hse.gov.uk/Statistics/causdis/deafness/index.htm (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Ruiters, M. A statistical review of the burden of occupational disease in South Africa. In Proceedings of the Southern African Institute for Occupational Hygiene Virtual Annual Conference, Online, 18 October–4 November 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. Injuries, Illnesses, and Fatalities. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/iif/ (accessed on 23 January 2021).

- Health and Safety Executive. HSG 254. Developing Process Safety Indicators. A Step-By-Step Guide for Chemical and Major Hazard Industries. Available online: https://books.hse.gov.uk/gempdf/hsg254.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Safework Australia. Measuring and Reporting on Work Health and Safety. Available online: https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/system/files/documents/1802/measuring-and-reporting-on-work-health-and-safety.pdf (accessed on 29 January 2024).

- Safework Australia. Lost Time Injury Frequency Rates. Available online: https://data.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/interactive-data/lost-time-injury-frequency-rates (accessed on 29 January 2024).

- Pawłowska, Z. Using lagging and leading indicators for the evaluation of occupational safety and health performance in industry. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2015, 21, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organisation. Guidelines on Occupational Safety Uidelines on Occupational Safety and Health Management Systems (ILO-OSH, 2001). Available online: https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/%40dgreports/%40dcomm/%40publ/documents/publication/wcms_publ_9221116344_en.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- International Council on Mining & Metals. Health and Safety Performance Indicators: Guidance. 2021. Available online: https://www.icmm.com/website/publications/pdfs/health-and-safety/2021/guidance_health-and-safety-indicators.pdf?cb=60005 (accessed on 14 February 2024).

- Lo, D. OHS Stewardship—Integration of OHS in Corporate Governance. Procedia Eng. 2012, 45, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meutia, I.; Kartasari, S.F.; Yaacob, Z. Stakeholder or Legitimacy Theory? The Rationale behind a Company’s Materiality Analysis: Evidence from Indonesia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizul Islam, M.; Deegan, C. Motivations for an organisation within a developing country to report social responsibility information: Evidence from Bangladesh. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2008, 21, 850–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velte, P. Determinants and financial consequences of environmental performance and reporting: A literature review of European archival research. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 340, 117916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junior, R.M.; Best, P.J.; Cotter, J. Sustainability Reporting and Assurance: A Historical Analysis on a World-Wide Phenomenon. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 120, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Administrative Regulations. 2003. Available online: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/225490.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2022).

- Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Act. 2002. Available online: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/a28-02ocr.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Department of Employment and Labour. Requirements for Approval as an Approved Inspection Authority: Occupational Health and Hygiene. 2012. Available online: https://www.labour.gov.za/DocumentCenter/Publications/Occupational%20Health%20and%20Safety/Requirements%20for%20approval%20as%20an%20Approved%20Inspection%20Authority%20Occupational%20Health%20and%20Hygiene.pdf (accessed on 17 August 2024).

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Standard Interpretations—Clarification on How the Formula is Used by OSHA to Calculate Incident Rates. 2016. Available online: https://www.osha.gov/laws-regs/standardinterpretations/2016-08-23 (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Mirza, S.; Mansouri, N.; Shirkhanloo, H. Promotion and evaluation of HSE indicators: Based on integrated management system in two chemical industries, Iran. J. Health Manag. 2023, 25, 541–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). OECD Guidance on Safety Performance Indicators: A Companion to the OECD Guiding Principles for Chemical Accident Prevention, Preparedness and Response. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2003/11/oecd-guidance-on-safety-performance-indicators_g1gh39b5/9789264019119-en.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Cambon, J.; Guarnieri, F.; Groeneweg, J. Towards a new tool for measuring Safety Management Systems performance. In Proceedings of the Second Resilience Engineering Symposium, Antibes, France, 8–10 November 2006. [Google Scholar]

- European Agency for Safety and Health. Key Performance Indicators. 2016. Available online: https://oshwiki.osha.europa.eu/en/themes/key-performance-indicators (accessed on 21 January 2024).

- Xue, C.; Tang, L.; Walters, D. Occupational health and safety Indicators and under-reporting: Case studies in Chinese shipping. Ind. Relat. 2019, 74, 141–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coetzee, C.M.; van Staden, C.J. Disclosure responses to mining accidents: South African evidence. Acc. Forum. 2011, 35, 232–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Companies Act, 2008 (No. 71 of 2008). Available online: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/321214210.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2022).

- Johannesburg Stock Exchange. JSE’s Sustainability and Climate Disclosure Guidance. Available online: https://group.jse.co.za/sustainability/climate-disclosure-guidance (accessed on 19 October 2024).

- Global Reporting Initiative. GRI 403: Occupational Health and Safety. 2018. Available online: https://esgdocs.sustainability-report.kr/en/GRI_Standards_2021/GRI_403__Occupational_Health_and_Safety_2018/ (accessed on 11 February 2024).

- Global Reporting Initiative. GRI 101: Foundation. 2016. Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/standards/media/1036/gri-101-foundation-2016.pdf (accessed on 8 July 2020).

- Bradford, W.C. “Because that’s where the money is”: A theory of corporate legal compliance. J. Bus. Entrep. Law. 2015, 8, 337. [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Organisation. Collecting Data and Measuring Key Performance Indicators on Occupational Safety and Health Interventions. A Guidebook for Implementers. 2022. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---protrav/---safework/documents/publication/wcms_864235.pdf (accessed on 29 January 2024).

- Basso, B.; Carpegna, C.; Dibitonto, C.; Gaido, G.; Robotto, A.; Zonato, C. Reviewing the safety management system by incident investigation and performance indicators. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2004, 17, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mine Health and Safety Council. New Mine Health and Safety Milestones for Adoption Beyond. Available online: https://www.mineralscouncil.org.za/component/jdownloads/?task=download.send&id=2342&catid=7&m=0 (accessed on 16 November 2024).

- Safework Australia. Issues in the Measurement and Reporting of Work Health and Safety Performance: A Review. 2013. Available online: https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/system/files/documents/1703/issues-measurement-reporting-whs-performance.pdf (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Johannesburg Stock Exchange. JSE Launches Sustainability and Climate Change Disclosure Guidance for Listed Companies. Available online: https://www.jse.co.za/news/news/jse-launches-sustainability-and-climate-change-disclosure-guidance-listed-companies#:~:text=JSE%20launches%20sustainability%20and%20climate,and%20governance%20(ESG)%20disclosure (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Statistics South Africa. Quarterly Labour Force Survey. Quarter 4. 2020. Available online: http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0211/P02114thQuarter2020.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2021).

- Sinelnikov, S.; Inouye, J.; Kerper, S. Using leading indicators to measure occupational health and safety performance. Saf. Sci. 2015, 72, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahaya, F.R.; Porter, S.; Tower, G.; Brown, A. Coercive pressures on occupational health and safety disclosures. J. Account. Emerg. Econ. 2017, 7, 318–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Affengruber, L.; Wagner, G.; Waffenschmidt, S.; Lhachimi, S.K.; Nussbaumer-Streit, B.; Thaler, K.; Griebler, U.; Klerings, I.; Gartlehner, G. Combining abbreviated literature searches with single-reviewer screening: Three case studies of rapid reviews. Syst. Rev. 2020, 9, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nama, N.; Hennawy, M.; Barrowman, N.; O’Hearn, K.; Sampson, M.; McNally, J.D. Successful incorporation of single reviewer assessments during systematic review screening: Development and validation of sensitivity and work-saved of an algorithm that considers exclusion criteria and count. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satiti, A.D.R.; Suhardjanto, D.; Widarjo, W.; Honggowati, S. Social contracts and occupational health and safety disclosure: Evidence from companies in Indonesia. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2025, 12, 2451130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Safety and Health Sustainability. Current Practices in Occupational Health & Safety Sustainability Reporting. Available online: https://aiha-assets.sfo2.digitaloceanspaces.com/AIHA/resources/CSHS/CSHS_SustainReport_2013_FinalZ.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Gardiner, E. Evaluating the quality of WHS disclosures by ASX100 companies: Is mandatory WHS reporting necessary? Saf. Sci. 2022, 153, 105798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilling, M. Company characteristics and occupational health and safety disclosures: A quantitative review of Australian annual reports. In Proceedings of the Fourth Asia Pacific Interdisciplinary Research in Accounting Conference, Singapore, 2–3 July 2004; Singapore Management University: Singapore, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Tsalis, T.A.; Stylianou, M.S.; Nikolaou, I.E. Evaluating the quality of corporate social responsibility reports: The case of occupational health and safety disclosures. Saf. Sci. 2018, 109, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Villiers, C.; van Staden, C.J. Can less environmental disclosure have a legitimising effect? Evidence from Africa. Account. Organ. Soc. 2006, 31, 763–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Employment and Labour. The Profile of Occupational Health and Safety in South Africa. Available online: https://www.labour.gov.za/DocumentCenter/Publications/Occupational%20Health%20and%20Safety/The%20Profile%20Occupational%20Health%20and%20Safety%20South%20Africa.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Rodriguez, R.R.; Saiz, J.J.A.; Bas, A.O. Quantitative relationships between key performance indicators for supporting decision-making processes. Comput. Ind. 2009, 60, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjellén, U. The safety measurement problem revisited. Saf. Sci. 2009, 47, 486–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, A. Why safety performance indicators? Saf. Sci. 2009, 47, 479–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Safety and Health Sustainability. Performance Standards. Available online: https://www.aiha.org/public-resources/center-for-safety-health-sustainability/center-for-safety-health-sustainability-resources (accessed on 21 October 2025).

| Industry Category | Total Listed Companies (274 Companies) | Number and Percentage of Top 150-Companies Included in the Study |

|---|---|---|

| Basic materials | 45 | 28 (9.9%) |

| Consumer goods | 21 | 11 (4%) |

| Consumer services | 38 | 25 (9.1%) |

| Financial | 96 | 54 (19.7%) |

| Healthcare | 7 | 4 (1.5%) |

| Industrial | 44 | 16 (5.8%) |

| Oil and gas | 3 | 1 (0.4%) |

| Technology | 14 | 7 (2.6%) |

| Telecommunications | 6 | 4 (1.5%) |

| Total | 274 | 150 (54.5%) |

| Sector | Number of Companies Reporting (Total in Study) | Percentage (%) of Companies Reporting | Total Number of Lagging Indicators Reported |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic materials | 26 (28) | 17% | 37 |

| Industrial | 13 (16) | 8,7% | 21 |

| Consumer goods | 9 (11) | 6% | 18 |

| Healthcare | 4 (7) | 2,7% | 24 |

| Consumer services | 11 (25) | 7,3% | 18 |

| Telecommunications | 4 (4) | 2,7% | 11 |

| Financial | 18 (54) | 12% | 18 |

| Technology | 2 (7) | 1,3% | 2 |

| Total | 87 (150) | 58% | - |

| Sector | Report Type | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annual Report | Integrated or Annual Integrated Report | ESG Reports | Sustainability Reports | Data Books | |

| Basic materials | 4 | 19 | 4 | 13 | 6 |

| Industrial | 0 | 13 | 2 | 3 | 0 |

| Consumer goods | 3 | 6 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Consumer services | 0 | 10 | 1 | 5 | 0 |

| Financial | 2 | 14 | 4 | 4 | 0 |

| Healthcare | 0 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Technology | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Telecommunications | 0 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Total | 9 | 71 | 12 | 32 | 8 |

| Lagging Indicator | BHP Group Limited | Glencore plc | Anglo American plc | Anglo American Platinum Ltd. | South32 Limited | Anglogold Ashanti | Harmony Gold Mining Company | Sibanye Stillwater Limited | African Rainbow Minerals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lost time injury frequency rate (LTIFR) | - | ✓ | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Total recordable injury frequency rate (TRIFR) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | - | - | ✓ | - | ✓ | - |

| Total recordable injuries/recordable injuries/cases | - | - | - | - | - | ✓ | - | ✓ | ✓ |

| Reportable injury frequency rate (RIFR) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Reportable injuries/injury on duty (IOD)/reportable incidents | ✓ | - | - | ✓ | - | - | - | - | ✓ |

| Occupational disease or occupational illness incidence/rate | ✓ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Occupational disease (OD) count | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | - | - | ✓ | - | ✓ |

| Fatalities/fatal injuries | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Fatality frequency rate (FIFR) | - | ✓ | - | - | - | - | - | ✓ | - |

| Medical treatment case (MTC) | - | - | - | - | - | ✓ | - | - | - |

| First aid case (FAC) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Lost time injuries (LTI)/lost time incidents | - | - | - | ✓ | - | ✓ | - | ✓ | ✓ |

| Recordable injuries | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Serious injury frequency rate (SIFR) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✓ | - |

| High potential injury frequency | ✓ | - | - | ✓ | - | ✓ | - | - | - |

| Total recordable injury frequency (TRIF) or (TIFR) | ✓ | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✓ | - |

| High consequence injury frequency | ✓ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Number of recordable work-related injuries | ✓ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Number of high consequence work-related injuries | ✓ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| High potential injuries (counts) | ✓ | - | - | - | - | ✓ | - | - | - |

| Occupational exposure reduction trend over time | ✓ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Severity rate | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✓ |

| Total recordable fatalities | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Life-altering injuries | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Total recordable cases | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Fatal injury frequency rate | - | - | - | - | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | - |

| Medical treatment case frequency rate | - | - | - | - | - | ✓ | - | - | - |

| Serious injuries/number of severe occupational injuries | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✓ | - |

| Medically treated injury frequency rate (MTIFR) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✓ | - |

| Lagging Indicator | Bidvest Group | Wilson Bayly Holmes-Ovcon Limited | Afrimat Limited | Super Group Limited | Reunert Limited | Grindrod Limited | PPC Limited | Raubex Group Limited | KAP Limited | CA Sales Holdings Limited | Hudaco Industries Limited | Nampak Limited | Bell Equipment Limited |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lost time injury frequency rate (LTIFR) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | - | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | - | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Total recordable injury frequency rate (TRIFR) | - | - | ✓ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Total recordable injuries/recordable injuries/cases | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✓ |

| Reportable injury frequency rate (RIFR) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✓ | - | - | - | - | - |

| Reportable injuries/injury on duty/reportable incidents | - | ✓ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✓ | - |

| Occupational disease count | - | - | - | - | ✓ | - | ✓ | - | ✓ | - | - | - | - |

| Fatalities/fatal injuries | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | - | ✓ | - | ✓ | - |

| Fatality frequency rate/FIFR | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✓ | ✓ | - | - | - | - | - |

| Medical treatment case (MTC) | - | - | ✓ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| First aid case (FAC) | - | - | ✓ | - | - | ✓ | ✓ | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Lost time injuries/incidents (LTI) | - | ✓ | - | - | - | ✓ | ✓ | - | ✓ | - | ✓ | - | - |

| Injuries | - | - | - | - | ✓ | - | ✓ | - | - | ✓ | - | - | - |

| High potential injuries (counts) | - | - | ✓ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Lost workday cases/days lost to WR accidents or illness/days lost due to LTI | - | - | - | - | ✓ | - | - | - | - | ✓ | - | - | - |

| Accidents | - | - | - | ✓ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Recordable case rate | - | ✓ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Compensation for occupational injuries and diseases (no lost time) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✓ | - | - | - | - |

| Total compensation for occupational injuries and diseases | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✓ | - | - | - | - |

| Lost time injury severity rate | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✓ | - | - |

| All incidence frequency rate | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✓ | - | - |

| Production injury frequency rate (PIFR) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✓ |

| Lagging Indicator | Anheuser-Busch Inbev | Compagnie Fin Richemont | British American Tobacco | Tiger Brands Limited | AVI Limited | Oceana Group Limited | RCL Foods Limited | Premier Group Limited | Astral Foods Limited |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total recordable case frequency rate (TRCFR) | - | - | - | ✓ | - | - | - | - | - |

| Lost time injury frequency rate (LTIFR) | - | - | - | ✓ | - | ✓ | ✓ | - | ✓ |

| Total recordable injury frequency rate (TRIFR) | - | - | ✓ | - | - | - | ✓ | - | - |

| Total recordable injuries/recordable injuries/cases | ✓ | - | - | - | - | ✓ | - | - | - |

| Occupational disease or occupational illness incidence/rate | - | ✓ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Occupational disease count | - | ✓ | - | - | - | - | ✓ | - | - |

| Fatalities/fatal injuries | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Fatality frequency rate/FIFR | - | - | - | ✓ | - | - | ✓ | - | - |

| Medical treatment case (MTC) | - | - | - | ✓ | - | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| First aid case | - | - | - | ✓ | - | - | ✓ | - | ✓ |

| Lost time injuries (LTI)/incidents | ✓ | - | ✓ | - | - | - | - | ✓ | ✓ |

| Recordable injuries | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Serious injury frequency rate | - | - | ✓ | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Number of recordable work-related injuries | - | ✓ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| lost time incidence rate | - | - | ✓ | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Disabling injury cases | - | - | - | - | ✓ | - | - | - | - |

| High consequence cases | - | ✓ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Disabling injury frequency rate | - | - | - | - | ✓ | - | - | ✓ | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rikhotso, O. Disclosures of Occupational Health and Safety Performance Indicators: A Perspective from South African Listed Companies. Safety 2025, 11, 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11040114

Rikhotso O. Disclosures of Occupational Health and Safety Performance Indicators: A Perspective from South African Listed Companies. Safety. 2025; 11(4):114. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11040114

Chicago/Turabian StyleRikhotso, Oscar. 2025. "Disclosures of Occupational Health and Safety Performance Indicators: A Perspective from South African Listed Companies" Safety 11, no. 4: 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11040114

APA StyleRikhotso, O. (2025). Disclosures of Occupational Health and Safety Performance Indicators: A Perspective from South African Listed Companies. Safety, 11(4), 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11040114