Navigating Risks and Realities: Understanding Motorbike Taxi Usage and Safety Strategies in Yaoundé and Douala (Cameroon)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. From Literature Review to Theoretical Position

3. Data Collection and Analysis Process

3.1. Direct Observations

3.2. Semi-Structured Interviews

3.3. Questionnaire

4. Results

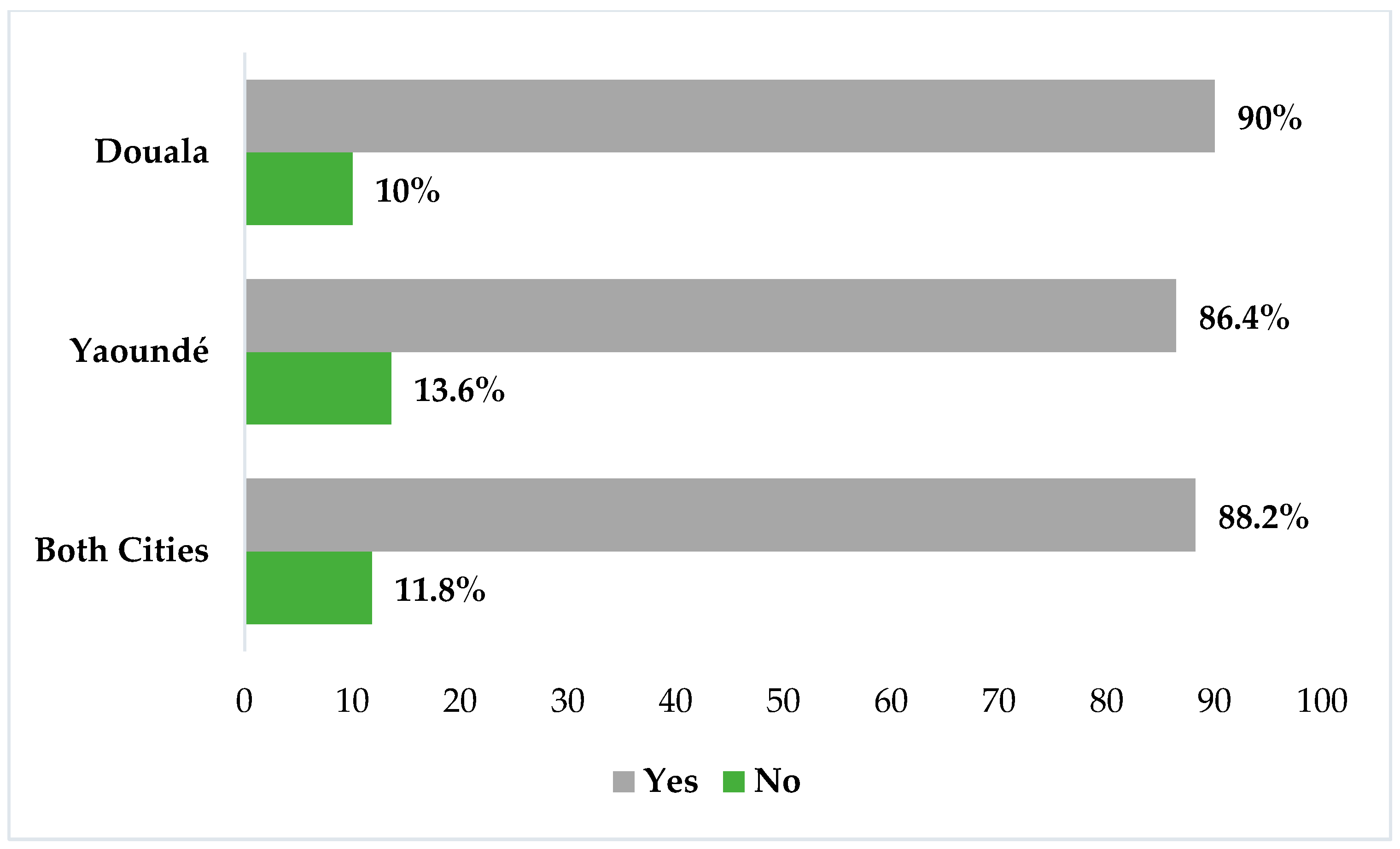

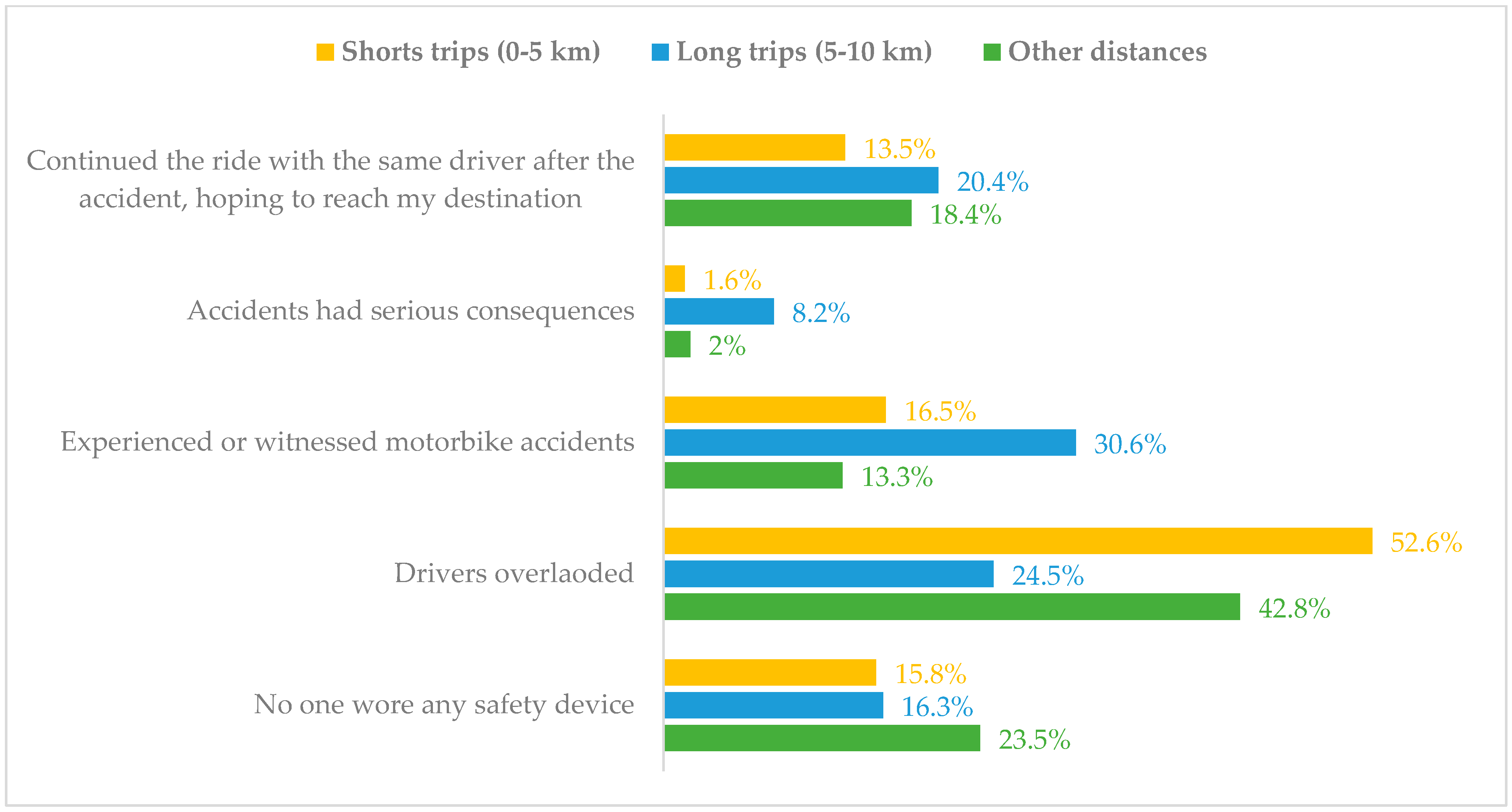

4.1. Perceptions of Motorbike Taxis as a High-Risk Mode of Transport

- Violation of traffic rules by motorbike taxi drivers

- Passenger vulnerability

“You can easily fall, get hurt, or even die in a motorbike accident. Motorbikes have only two wheels, making them more likely to fall. On a motorbike, the passenger’s body acts as the ‘shell,’ unlike in a taxi, where the four wheels and the car’s body provide protection”.[52]

- Victims or witnesses of accidents

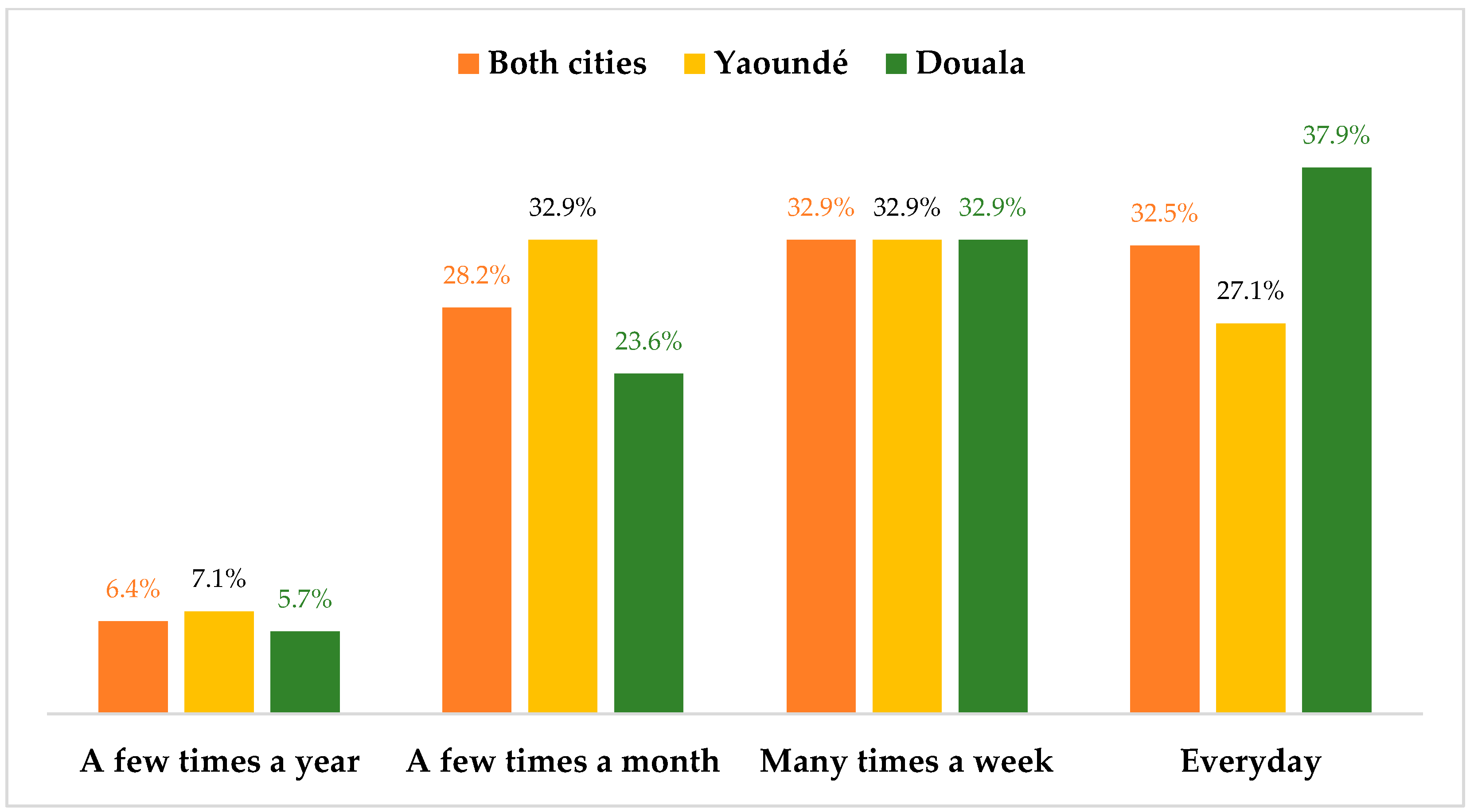

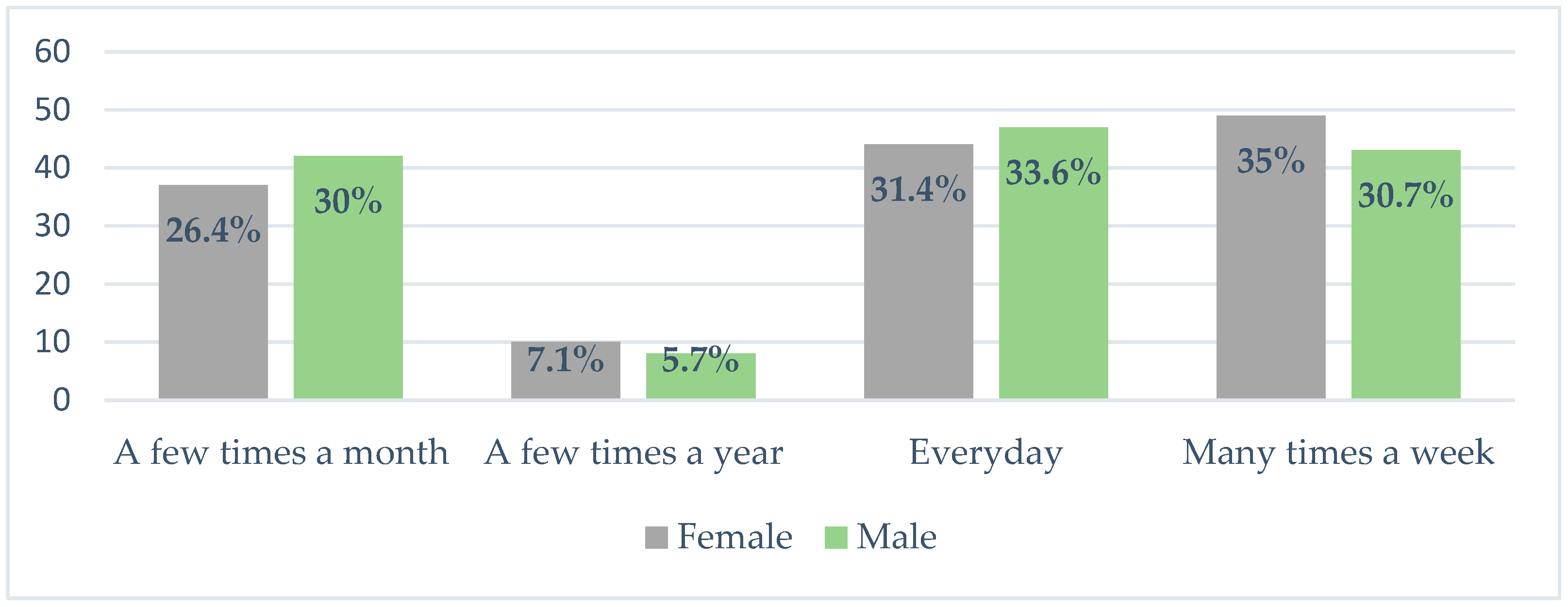

4.2. Reasons Behind the Continued Use of Motorbike Taxis

“When you’re the first customer in a taxi, no matter your destination, the driver stops every time he sees people on the side of the road to try and pick them up. Even if their destinations are closer than yours, the driver frequently stops dropping them off, which takes too long. But with a motorbike taxi, it’s quick. If you pay well, they take you along. And even when there’s an overload, it’s just a few people. That’s why motorbikes are always faster than taxis”.[58]

4.3. Passenger Strategies to Mitigate Motorbike Taxi Risks

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| City | High School | Primary School | University | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yaoundé | Effectif | 61 | 25 | 54 | 140 |

| % within level of study | 56.5% | 41.7% | 48.2% | 50.0% | |

| % of Total | 21.8% | 8.9% | 19.3% | 50.0% | |

| Douala | Count | 47 | 35 | 58 | 140 |

| % within level of study | 43.5% | 58.3% | 51.8% | 50.0% | |

| % of Total | 16.8% | 12.5% | 20.7% | 50.0% | |

| Total | Count | 108 | 60 | 112 | 280 |

| % within level of study | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | |

| % of Total | 38.6% | 21.4% | 40.0% | 100.0% | |

References

- Ndam, S.; Rérat, P. Cycling in African Cities: A Study Based on the Velomobility System in Yaounde and Douala (Cameroon). Appl. Mobilities, 2025; Ongoing. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz Olvera, L.; Guézéré, A.; Plat, D.; Pochet, P. Earning a Living, but at What Price? Being a Motorcycle Taxi Driver in a Sub-Saharan African City. J. Transp. Geogr. 2016, 55, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SUMP Douala. Sustainable Urban Mobility Plan of Douala; MobiliseYourCity: Douala City Council: Douala, Cameroon, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sustainable Urban Mobility Plan of Yaounde (SUMP Yaounde) MobiliseYourCity; Yaoundé City Council: Yaoundé, Cameroon, 2019.

- Amougou Mbarga, A. The Motorbike Taxis Phenomenon in the City of Douala: State Crisis, Identity and Social Regulation. A Cultural Studies Approach. Anthropol. Sociétés 2010, 34, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Keutcheu, J. Le «fléau des motos-taxis». Cah. D’études Afr. 2015, 509–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawel, A. Cameroon: Five Students Killed on Their Way to School. J. Cameroun 2023. Available online: https://camerounactuel.com/melong-cinq-eleves-tues-sur-le-chemin-de-lecole/#google_vignette (accessed on 31 March 2023).

- Luqman, M. Cameroon: 2 Deads in a Motorbike Accident in Douala. 237Actu.com. 2019. Available online: https://237actu.com/cameroun-2-morts-dans-un-accident-de-moto-a-douala/ (accessed on 31 March 2023).

- Tcheunteu Simo, J.S. Urban transport by motorcycle-taxi and health risk in Douala (Cameroon). Rev. Espace Territ. Sociétés Santé 2021, 4, 37–48. [Google Scholar]

- La Voix du Centre Motorbike Taxi Sector: There Is Danger in the House and the Authorities Are Looking Elsewhere. Actu Cameroun 2021.

- Baba Wame. Afrik. 25 July 2002. Available online: https://www.afrik.com/les-moto-taxis-ou-la-danse-de-la-mort (accessed on 31 March 2023).

- Ndam, S. Mobilities and Urban Violence in Cameroon. Analysis of Forms of Sociability in the Streets of Yaoundé and Douala. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Yaounde 1, Yaounde, Cameroon, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tsayid, G.E. Urban Transport: Over 70,000 Motorbike Taxis Registered. Cameroon Trib. Cameroonian Gov. Newsp. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Amougou, M.P. Promotion des valeurs civiques et participation au développement: Analyse de l’activité de transport par moto dans la ville de Yaoundé au Cameroun. Lang. Cult. Sociétés 2021, 7, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaffo, C.; Kamdem, P.; Tatsabong, B.; Diebo, L.M. L’integration des “Motos-Taxi” Dans le Transport Public au Cameroun ou L’informel a la Remorque de L’etat: Une Solution D’avenir au Probleme de Mobilite et de L’emploi Urbain en Afrique Subsaharienne. Yaoundé, Cameroon. 2012. Available online: http://www.sifee.org/static/uploaded/Files/ressources/contenu-ecole/douala/volet-2/1_SAMOURA_EXERCICE.pdf (accessed on 31 March 2023).

- Owona Ndounda, N. Cameroon’s Public Transport Policies from 1884 to 2017. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Yaounde 1, Yaounde, Cameroon, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kalieu, C. Surrgissement, Prolifération et Intégration des Motos-Taxis Dans les Villes Camerounaises: Les Exemples de Douala et Bafoussam. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Bretagne Occidentale, Brest, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Leka Essomba, A. Mobilités Quotidiennes et Identité Urbaine au Cameroun: Une Introduction à la Sociologie de la Circulation; Sciences Humaines et Sociales. Sciences Sociales; Connaissances et Savoirs: Saint-Denis, France, 2017; ISBN 978-2-7539-0507-8. [Google Scholar]

- Kouagheu, J. Au Cameroun, dans la Jungle des Motos-Taxis. Le Monde Afrique. 2020. Available online: https://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2020/02/03/au-cameroun-dans-la-jungle-des-motos-taxis_6028276_3212.html (accessed on 5 February 2022).

- Fofana, I.; Togola, I. Urbanisation et Nouveaux Modes de Transport Urbain En Afrique de l’Ouest: Cas de La Ville de Bamako (Mali). Eur. Sci. J. 2020, 16, 206–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fofana, M.; Sangaré, M. A Propos Des Accidents de La Route: Analyse Des Facteurs Associés Aux Accidents Des Motos-Taxis Dans Le Département de Korhogo. East Afr. Sch. Multidiscip. Bull. 2018, 1, 129–137. [Google Scholar]

- Kouakou Attien, J.-M.K. Les services collectifs de transport intra-urbain à Bouaké: Des offres de mobilité à hauts risques pour les populations. EchoGéo 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djouda Feudjio, Y.B. Les jeunes benskineurs au Cameroun: Entre stratégie de survie et violence de l’État. Autrepart 2014, 71, 97–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassi-Djodjo, I. Les Taxis-Motos: Un Transport de Crise dans la Ville de Bouaké (Côte d’Ivoire). Géotransports 2013, 2, 1. Available online: https://123dok.net/document/qvlk11dy-taxis-motos-transport-crise-ville-bouake-cote-ivoire.html (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Dindji Médé, R.; Diabagaté, A.; Houenenou Kouadio, D.; Brou, É.K. Émergence De Taxi-Motos Et Recomposition SpatioÉconomique À Korhogo: Les Taxi-Villes Entre Stratégies D’adaptation et Désespoir. Eur. Sci. J. ESJ 2016, 12, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemajou, A.; Jaligot, R.; Bosch, M.; Chenal, J. Assessing Motorcycle Taxi Activity in Cameroon Using GPS Devices. J. Transp. Geogr. 2019, 79, 102472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahabana, M. Le Joola, Ndiaga Ndiaye, Cars Rapides…: Les Victimes Des Transports En Commun, l’affaire de Tous? Transp. Économie Polit. Société 2003, 419, 177. [Google Scholar]

- Lomme, R. La réforme des transports publics urbains à l’épreuve de l’intégration du secteur informel. Afr. Contemp. 2004, 210, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olvera, L.D.; Plat, D.; Pochet, P. Sécurité Personnelle et Mobilité Quotidienne en Afrique Subsaharienne. Le Cas de Dakar; Ecole de Management de Normandie: Caen, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Noble, J. L’insécurité personnelle dans les transports en commun. Déviance Société 2015, 39, 343–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, J.; Bamba, V.; Kassi-Djodjo, I. Multiple Marginality and the Emergence of Popular Transport: ‘Saloni’ Taxi-Tricycles in Abidjan, Ivory Coast. Cybergeo Eur. J. Geogr. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbamaro, M. Apport des taxi-tricycles dans la mobilité des personnes à Lomé (Togo). Espace Géographique Société Marocaine 2022, 1, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agheyisi, J.E. Privileging Commuters’ Mobility in Neighbourhood Access: Analysis of Tricycle Taxi Operations in Benin City, Nigeria. Geoforum 2021, 127, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouhan, S.S.; Kathuria, A.; Chalumuri, R.S. Powered Two-Wheeler Riding Behavior and Strategies to Improve Safety: A Review. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. Engl. Ed. 2024, 11, 1378–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodegast, P.; Maier, S.; Kneifl, J.; Fehr, J. On Using Machine Learning Algorithms for Motorcycle Collision Detection. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2024, 6, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignot, D.; Carnis, L.; Fernandez, E.; Usami, D.-S.; Welsh, R. Elements of Evaluation for the African Road Safety Action Plan 2011–2020, Based on Saferafrica Project; CODATU: Dakar, Senegal, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mignot, D.; Carnis, L. Difficulties in Implementing Evidence-Based Measures in Some African Countries; FERSI: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, S.V.; Kluppels, L.; Cardoso, J.L. Road Safety Capacity Building Actions in Africa. Results from the SaferAfrica Project. Transp. Res. Procedia 2023, 72, 3474–3480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukumar, G.M.; Patel, N.; Gururaj, G.; Kumar, A.; Anucheth, M.N.; Bachani, A.G. Helmet Protection Paradox for Powered Two-Wheeler Users: Concerns in Data Misinterpretation and Need for Improved Data Systems. J. Neurosci. Rural Pract. 2021, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Transport Safety Council. Reducing Road Deaths among Powered Two Wheeler Users (PIN Flash 44); European Transport Safety Council: Brussels, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Z.; Hosseini, A.; Chen, D.; Shoghli, O.; Heydarian, A. Real-Time Roadway Obstacle Detection for Electric Scooters Using Deep Learning and Multi-Sensor Fusion. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.03171. [Google Scholar]

- Le Breton, D. Sociologie du Risque, 2nd ed.; Que sais-je: Paris, France, 2017; ISBN 978-2-13-079505-6. [Google Scholar]

- Soulé, B.; Corneloup, J. Jeunes et Prises de Risque Sportives. Vers Une Approche Sociologique Contextualisée. Corps Cult. 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soulé, B.; Corneloup, J. Jeunes et pratiques sportives à risque: Vers une approche sociologique contextualisée. Rev. Corps Cult. 1998, 3, 107. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, J.-F.; Pacom, D. Choosing a High-Risk Occupation: Canadian Infantry Soldiers in Wartime. Rev. Jeunes Société 2022, 6, 27–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikwunze, A.N.; Djomou, A.; Ndanga, M. Assessing the Risk Profile of Motorised Two-Wheelers in Urban Cameroon: Trauma Trends in Douala and Yaoundé. J. Afr. Urban Stud. 2023, 8, 115–133. [Google Scholar]

- Yaounde City Council (YCC) Order N° 005/CUY/DST/12 to Delimit the Zones of Circulation of Motorbikes for Hire in the City of Yaounde. Available online: http://yaounde.cm/ (accessed on 3 February 2022).

- Douala City Council (DCC) Order N° 03/CUD/SG/2012 to Delimit the Traffic Zones of Commercial Motorbikes in the City of Douala. Available online: https://douala.cm (accessed on 18 March 2022).

- Bardin, L. L’analyse de Contenu, 7th ed.; Presses Universitaires de France: Paris, France, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtsson, M. How to Plan and Perform a Qualitative Study Using Content Analysis. NursingPlus Open 2016, 2, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yannick, M. (Independent Researcher, Douala, Cameroon). Interview with the authors, unpublished material not intended for publication, 2022.

- Donald, T. (PhD student, Yaoundé, Cameroon). Interview with the authors, unpublished material not intended for publication, 2023.

- Roland, G. (Tailor, Yaoundé, Cameroon). Interview with the authors, unpublished material not intended for publication, 2022.

- Myriam, A. (Clothes trader, Douala, Cameroon). Interview with the authors, unpublished material not intended for publication, 2023.

- Mohamed, N. (Motorbike taxi driver, Yaoundé, Cameroon). Interview with the authors, unpublished material not intended for publication, 2022.

- Sylvain, N. (Craftsman, Douala, Cameroon). Interview with the authors, unpublished material not intended for publication, 2022.

- Yvonne, T. (Hairdresser, Douala, Cameroon). Interview with the authors, unpublished material not intended for publication, 2022.

- Patrick, B. (Civil servant, Yaoubdé, Cameroon). Interview with the authors, unpublished material not intended for publication, 2022.

- Blaise, T. (Teacher, Yaoundé, Cameroon). Interview with the authors, unpublished material not intended for publication, 2022.

- Mbouombouo, P. Détournements Des Trottoirs à Yaoundé: Entre Logiques Économico-Sociales et Marginalité Urbaine. In C’est ma Ville!» De L’appropriation et du Détournement de L’espace Public; L’Harmattan: Paris, France, 2005; pp. 247–259. [Google Scholar]

- Ousman, T. (Cargo vehicle driver, Douala, Cameroon). Interview with the authors, unpublished material not intended for publication, 2022.

- Mariam, B. (Street vendor, Yaoundé, Cameroon). Interview with the authors, unpublished material not intended for publication, 2022.

- Nadine, B. (Accountant, Douala, Cameroon). Interview with the authors, unpublished material not intended for publication, 2022.

- Eric, F. (Taxi driver, Yaoundé, Cameroon). Interview with the authors, unpublished material not intended for publication, 2022.

- Mounir, J. (Student, Douala, Cameroon). Interview with the authors, unpublished material not intended for publication, 2022.

- Dongmo, S.; Mechanic, Douala, Cameroon. Interview with the authors, unpublished material not intended for publication, 2022.

- Mirelle, T. (Street vendor, Douala, Cameroon). Interview with the authors, unpublished material not intended for publication, 2022.

- Crozier, M.; Friedberg, E. Actors and Systems: The Politics of Collective Action, 1st ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Ndam, S. La laïcité au Cameroun: Pratiques religieuses et rapport(s) au travail dans les services publics. Rev. Int. Francoph. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, W.J.; Judd, D.K.; Gale, M.; Finlinson, H.G. Religion, Mental Health, and the Latter-Day Saints: A Review of Literature 2005–2022. Religions 2023, 14, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janaba, E. (Electrician, Douala, Cameroon). Interview with the authors, unpublished material not intended for publication, 2023.

- Boutin, P.-É. Les droits des voyageurs par autocar. Transp. Urbains 2015, 127, 12–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epee Ekwalla, J. Les Syndicats Au Cameroun. Genèse, Crises et Mutations; L’Harmattan: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Temgoua, J.B. Afrik. 5 May 2004. Available online: https://www.afrik.com/les-motos-taxis-defient-les-pouvoirs-publics (accessed on 25 May 2023).

- Aloko-Nguessan, J.; Guelé Gue, P. Intégration des motos-taxis dans le réseau de transport public: Cas du département d’Oumé (Côte d’Ivoire). Rev. Can. Géographie Trop. 2016, 3, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Goguel d’Allondans, T. David Le Breton, Conduites à risque, Paris, PUF (coll. Quadrige), 2002. Rev. Sci. Soc. 2003, 197. [Google Scholar]

| Category | Interview Locations | Key Topics Explored |

|---|---|---|

| Motorbike taxi drivers | Parking areas | -Areas and times of day when they are most solicited by passengers -Forms of passenger negotiation (bargaining, compromise, etc.), -Passenger behaviour during journeys. |

| Drivers of other public transport modes | Service stations, car washes, bus stations | -Neighbourhoods and streets where they travel more or less frequently -Fares applied in these areas. |

| Motorbike taxi passengers | Streets | -Perceptions and knowledge of risks associated with motorbike taxis -Comparison of safety levels with other public transport modes (e.g., taxis, coaches) -Reasons for preferring motorbike taxis and preferred times of use -Behaviours to prevent accidents or minimise injuries. |

| Analysis Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Transcription | All interviews were transcribed to prepare for detailed analysis |

| Semantic Units Formation | Themes were extracted and combined with observation notes and photographs taken on the streets |

| Theme Categorization | Identified themes were organised into coherent categories |

| Interpretative Analysis | Inferences were drawn to interpret the collected information and provide deeper insights into the dynamics of motorbike taxi use |

| Variable | Category | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Have you used a motorbike in the past 12 months? | Yes | 280 | 100% |

| Gender | Male | 140 | 50.0% |

| Female | 140 | 50.0% | |

| City | Douala | 140 | 50.0% |

| Yaoundé | 140 | 50.0% | |

| I own a personal car | No | 234 | 83.6% |

| Yes | 46 | 16,4% | |

| Perceived Risk | Yes (risky) | 247 | 88.2% |

| No (not risky) | 33 | 11.8% | |

| Faster than other transport? | Yes | 250 | 89.3% |

| No | 30 | 10.7% | |

| Inaccessible Area Coverage | Yes (reach inaccessible) | 264 | 94.3% |

| No | 16 | 5.7% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kouomoun, A.; Ndam, S.; Chenal, J.; Kemajou, A. Navigating Risks and Realities: Understanding Motorbike Taxi Usage and Safety Strategies in Yaoundé and Douala (Cameroon). Safety 2025, 11, 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11020061

Kouomoun A, Ndam S, Chenal J, Kemajou A. Navigating Risks and Realities: Understanding Motorbike Taxi Usage and Safety Strategies in Yaoundé and Douala (Cameroon). Safety. 2025; 11(2):61. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11020061

Chicago/Turabian StyleKouomoun, Abdou, Salifou Ndam, Jérôme Chenal, and Armel Kemajou. 2025. "Navigating Risks and Realities: Understanding Motorbike Taxi Usage and Safety Strategies in Yaoundé and Douala (Cameroon)" Safety 11, no. 2: 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11020061

APA StyleKouomoun, A., Ndam, S., Chenal, J., & Kemajou, A. (2025). Navigating Risks and Realities: Understanding Motorbike Taxi Usage and Safety Strategies in Yaoundé and Douala (Cameroon). Safety, 11(2), 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11020061