Effectiveness of Toolbox Talks as a Workplace Safety Intervention in the United States: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Toolbox Talks

1.2. The Significance of Toolbox Talks

1.3. Theoretical Framework

1.4. Objectives

- What is the reported effectiveness of TBTs as an occupational safety intervention?

- What challenges and barriers are associated with their implementation?

- What best practices and delivery methods enhance their impact?

2. Materials and Methods

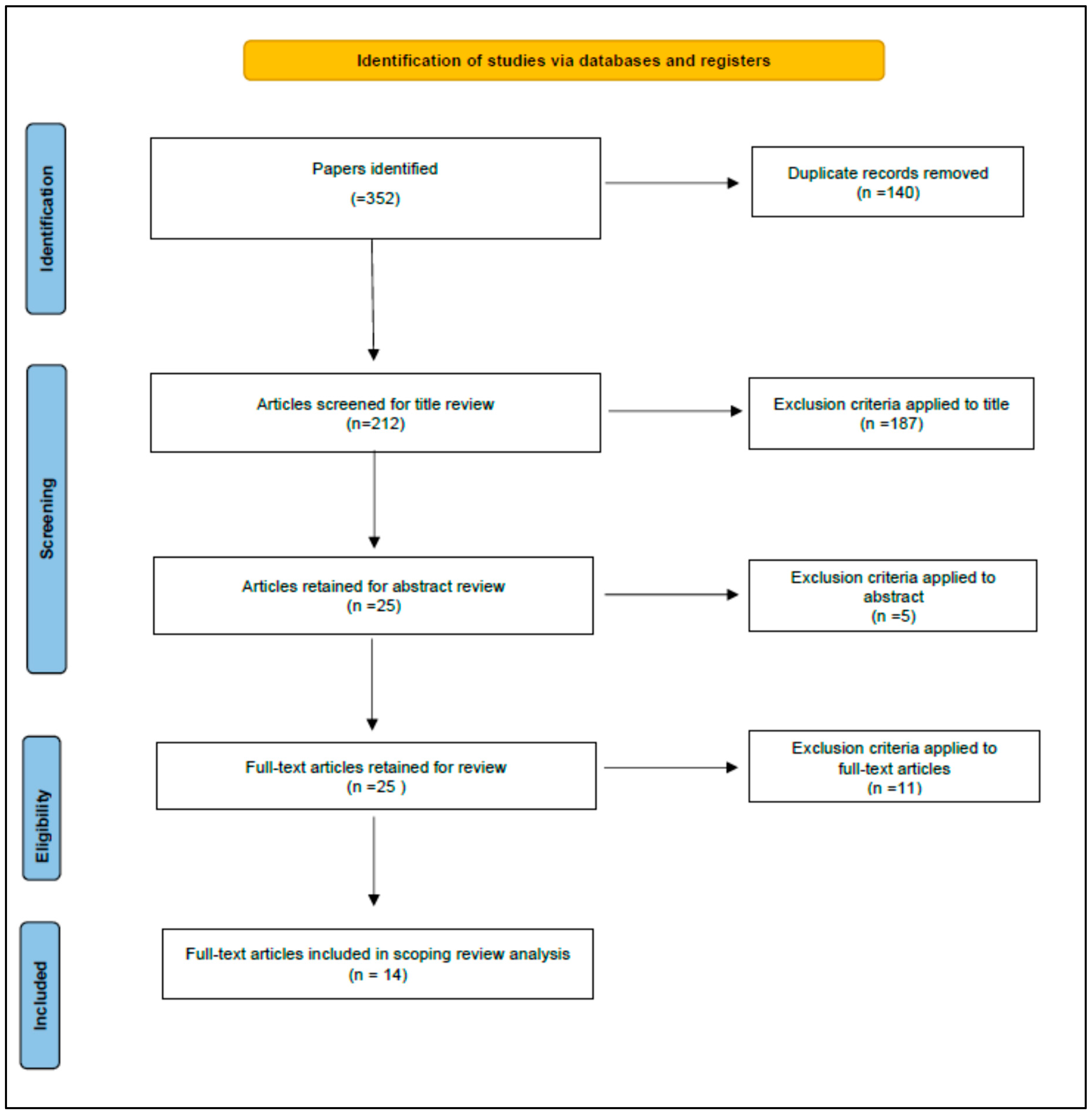

2.1. PRISMA Scoping Review

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

- (i)

- Involve the use of TBTs as a component of OSH training and educational intervention, and/or be used as a major component of the study design;

- (ii)

- Published in English between the years 2000 and 2024;

- (iii)

- Focus on work groups or the worker population in the United States;

- (iv)

- Report either qualitative or quantitative results as an outcome of the educational safety training intervention.

2.3. Measures of Effectiveness

- Safety Knowledge (SK): Defined as factual or procedural knowledge gained through training (e.g., understanding emergency procedures or safe equipment use).

- Safety Attitudes and Beliefs (SAB): Defined as psychological or emotional factors such as safety mindset, perceived risks, and self-efficacy.

- Safety Behavior (SB): Observable safety-related actions (e.g., using PPE or completing safety checks).

- Health Outcomes (HO): Measurable health effects or reductions in injury risk or exposure.

2.4. Exclusion Criteria

2.5. Search Strategy

2.6. Screening and Data Charting

2.7. Narrative Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Narrative Summary of Toolbox Talk Evaluation and Effectiveness

- Safety Knowledge (SK): Following post-TBT interventions, all studies assessing SK reported improvements in workers’ safety knowledge, varying from slight to considerably high. Several studies highlighted increased worker knowledge in the areas of identifying risk hazards and applying safe work practices. These findings affirm TBTs’ ability to enhance factual safety knowledge through brief targeted instruction.

- Safety Attitudes and Beliefs (SAB): Studies assessing SAB demonstrated that improved SK frequently translated into workers’ safety perceptions, attitudes, and beliefs being shaped leading to improved hazard awareness and greater confidence in their ability to perform job tasks safely. This relationship between knowledge and attitudinal changes was emphasized in studies by Rovai et al. [24], Al-Shabbani [30], Eggerth et al. [15], Kaskutas et al. [9,11,12], and Olson et al. [13]. These findings suggest that well-structured TBTs can influence not only what workers know but also how they think about safety.

- Safety Behavior (SB): Behavioral outcomes varied, though most studies noted positive changes in worker practices. For example, Brnich et al. reported modest increases in observable safety awareness among older, more experienced mining workers [26]. Other studies showed stronger behavioral impacts including compliance with regulatory standards [28], increased use of personal protective equipment (PPE) [12,27,29], improved safety communication, adherence to safety behaviors, and better fall prevention practices [9,11,12,13]. Several TBT studies that engaged workers through tailored messages and participatory formats demonstrated effectiveness in shifting daily behaviors and worksite norms. These studies also documented safer work practices and improved actions for protecting health [27,29].

- Health Outcome (HO): Although less frequently assessed, health outcomes were documented in two studies, both of which demonstrated broader organizational benefits, including reductions in workplace exposures and improved protective behaviors. Studies by Caban-Martinez et al. and Kaskutas et al. found that TBTs contributed to safer practices at the team level, reinforcing the value of TBTs in promoting not just individual behavior change but system-level safety culture improvements [12,27].

3.3. Challenges Identified

3.4. Best Practices Identified

4. Discussion

4.1. Practical Implications

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Database | (“Toolbox Talks” [All Fields]) AND (“Workplace Safety” [MeSH Terms] OR “Safety” [All Fields]) AND “Intervention” [All Fields] | (“Tailgate Talks” [All Fields]) AND (“Workplace Safety” [MeSH Terms] OR “Workplace Safety” [All Fields]) AND “Intervention” [All Fields] |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | 106 | 2 |

| Scopus | 149 | 23 |

| Google Scholar | 16 | 8 |

| ProQuest | 45 | 3 |

| Reference | Challenges or Barriers Identified | Best Practices Identified | Study Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reed et al. [22] | Limited engagement among experienced workers due to perceived redundancy of safety information. | Tailor safety messages to worker experience levels to address skepticism. | Chemical processing |

| Rice et al. [28] | Reduced interaction and engagement in text-message-based TBTs compared to in-person formats. | Supplement text message TBTs with periodic in-person discussions to improve engagement. | Construction (residential) |

| Rovai et al. (2020)[24] | Production pressures limited time for comprehensive TBT delivery. | Schedule TBTs at the start of shifts to integrate safety messages seamlessly with workflows. | Dairy farming |

| Al-Shabbani[30] | High worker turnover disrupted continuity in pre-task TBT exposure. | Use pre-task TBTs that are task-specific and delivered daily to reinforce learning. | Highway maintenance, Kentucky |

| Eggerth et al.[15] | Inconsistent participation among transient construction workers. | Integrate narratives into TBTs to make safety messages relatable and engaging. | Construction (residential) |

| Caban-Martinez et al. [27] | Language barriers and cultural differences hindered PPE training engagement. | Develop culturally tailored, multilingual TBT materials to engage diverse workforces. | Construction |

| Kaskutas et al.[11] | High crew turnover reduced continuity of fall prevention messaging across worksites. | Develop sustained TBT programs with small-group discussions and follow-ups. | Construction (residential) |

| Kaskutas et al.[11] | Limited foreman-to-crew communication on safety priorities led to inconsistent safety practices. | Implement tailored TBTs addressing site-specific hazards with active crew participation. | Construction(residential) |

| Olson et al. [13] | Supervisor was reluctant to adopt new materials due to time constraints. | Use simplified visual aids like line drawings to improve hazard identification and efficiency. Brief, formatted, and scripted TBTs save time and work well for supervisors. | Construction (residential) |

| Kaskutas et al.[11] | Safety communication gaps persisted between foremen and crewmembers. | Increase frequency of TBTs and reinforce messages using hands-on training and demonstrations. | Construction (residential) |

| Kaskutas et al. [9] | Inconsistent communication practices among foremen reduced safety engagement. | Conduct foremen-led TBTs with a focus on hazard-specific mentoring. | Construction (residential) |

| Harrington et al.[25] | Lack of supervisor training in participatory techniques limited TBT effectiveness. | Train supervisors in participatory methods to encourage worker engagement. | Construction |

| Sparer et al.[32] | Resistance to site-wide recognition programs from subcontractors. | Use team-wide recognition initiatives to reinforce positive safety behaviors and communication. | Construction (commercial) |

| Harrington et al.[25] | Worker disengagement during standard TBTs due to lack of participatory elements. | Train supervisors using participatory models to foster engagement during TBTs. | Construction |

References

- Michaels, D.; Barab, J. The occupational safety and health administration at 50: Protecting workers in a changing economy. Am. J. Public. Health 2020, 110, 631–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Labor. Department of Labor Encouraged by Decline in Worker Death Investigations. Updated 2024. Available online: https://www.dol.gov/newsroom/releases/osha/osha20241104-0 (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/ (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- National Safety Council-Save Lives, from the Workplace to Anyplace. Available online: https://www.nsc.org/ (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- EuroStat. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/ (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Occupational Injuries in the Canadian Federal Jurisdiction: 2022 Annual Report. Employment and Social Development-Canada. 2022. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/services/health-safety/reports.html (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Dingwall, R.; Frost, S. Health and Safety in a Changing World, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kines, P.; Andersen, L.P.S.; Spangenberg, S.; Mikkelsen, K.L.; Dyreborg, J.; Zohar, D. Improving construction site safety through leader-based verbal safety communication. J. Saf. Res. 2010, 41, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaskutas, V.; Dale, A.M.; Lipscomb, H.; Evanoff, B. Fall prevention and safety communication training for foremen: Report of a pilot project designed to improve residential construction safety. J. Safety Res. 2013, 44, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Washington State Centers of Excellence. Toolbox Talks Continue to Grow. Updated 2024. Available online: https://coewa.org/blog/2024/4/26/toolbox-talks-continue-to-grow (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Kaskutas, V.; Jaegers, L.; Dale, A.M.; Evanoff, B. Toolbox talks: Insights for improvement. Prof Saf. 2016, 61, 33–37. [Google Scholar]

- Kaskutas, V.; Dale, A.M.; Lipscomb, H.; Evanoff, B. Fall prevention and safety communication training for construction foremen. Work Ind. Spec. Interest Sect. Q./Am. Occup. Ther. Assoc. 2014, 28. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0022437512001053 (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Olson, R.; Varga, A.; Cannon, A.; Jones, J.; Gilbert-Jones, I.; Zoller, E. Toolbox talks to prevent construction fatalities: Empirical development and evaluation. Saf. Sci. 2016, 86, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versteeg, K.; Bigelow, P.; Dale, A.M.; Chaurasia, A. Utilizing construction safety leading and lagging indicators to measure project safety performance: A case study. Saf. Sci. 2019, 120, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggerth, D.E.; Keller, B.M.; Cunningham, T.R.; Flynn, M.A. Evaluation of toolbox safety training in construction: The impact of narratives. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2018, 61, 997–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robson, L.S.; Stephenson, C.M.; Schulte, P.A.; Amick, B.C., III; Irvin, E.L.; Eggerth, D.E.; Chan, S.; Bielecky, A.R.; Wang, A.M.; Heidotting, T.L.; et al. A systematic review of the effectiveness of occupational health and safety training. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health. 2012, 38, 193–208+ii. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knowles, M.S. Andragogy: Adult learning theory in perspective. Community Coll. Rev. 1978, 5, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, C.; Sheeran, P. The health belief model. Predict. Health Behav. 2005, 2, 28–80. [Google Scholar]

- Robson, L.; Stephenson, C.; Schulte, P.; Amick, B.; Chan, S.; Bielecky, A.; Wang, A.; Heidotting, T.; Irvin, E.; Eggerth, D.; et al. A Systematic Review of the Effectiveness of Training & Education for the Protection of Workers; Institute for Work & Health: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2010; p. 2127. [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, M.J.; Sarpy, S.A.; Smith-Crowe, K.; Chan-Serafin, S.; Salvador, R.O.; Islam, G. Relative effectiveness of worker safety and health training methods. Am. J. Public. Health. 2006, 96, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed, P.; Marin, L.S.; Zreiqat, M. Impact of toolbox training on risk perceptions in hazardous chemical settings: A case study from a bleach processing plant. ACS Chem. Health Saf. 2023, 30, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shabbani, Z.; Sturgill, R.; Dadi, G. Evaluating the effectiveness of toolbox talks on safety awareness among highway maintenance crews. In Construction Research Congress 2020: Safety, Workforce, and Education-Selected Papers from the Construction Research Congress 2020; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2020; pp. 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovai, M.; Carroll, H.; Foos, R.; Erickson, T.; Garcia, A. Dairy tool box talks: A comprehensive worker training in dairy farming. Front. Public. Health 2016, 4, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrington, D.; Materna, B.; Vannoy, J.; Scholz, P. Conducting effective tailgate trainings. Health Promot. Pract. 2009, 10, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brnich, M.J.; Derick, R.L., Jr.; Mallett, L.; Vaught, C. Innovative Alternatives to Traditional Classroom Health and Safety Training; Strategies for Improving Miners’ Training. 2002. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/mining/UserFiles/works/pdfs/IC9463.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Caban-Martinez, A.; Olano, H.; Sznol, J.; Chen, C.; Arheart, K.; Lee, D. Assessment of an interactive toolbox talk training on N95 respirator mask use among construction workers. ISEE Conf. Abstr. 2015, 2016, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, S.P.M.; Rimby, J.; Hurtado, D.A.; Gilbert-Jones, I.; Olson, R. Does sending safety toolbox talks by text message to residential construction supervisors increase safety meeting compliance? Occup. Health Sci. 2022, 6, 313–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparer, E.H.; Herrick, R.F.; Dennerlein, J.T. Development of a safety communication and recognition program for construction. New Solut. 2015, 25, 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-shabbani, Z. Improving Safety Performance of Highway Maintenance Crews Through Pre-Task Safety Toolbox Talks. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sparer, E.H.; Murphy, L.A.; Taylor, K.M.; Dennerlein, J.T. Correlation between safety climate and contractor safety assessment programs in construction. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2013, 56, 1463–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sparer, E.H. Improving health and safety in construction: The intersection of programs and policies, work organization, and safety climate. Doctoral Dissertation, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

| * Effectiveness | TBT Intervention/Objective | Study Approach | Participants/Setting | Outcomes/Key Findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SK, SAB | Reed et al., [22] | To evaluate impacts of TBT training on three dimensions of risk perception—knowledge, dread (fear), and control of hazardous chemicals. | Quasi-experimental; 20 min TBT training sessions held over a 4-month period using pre- and post-surveys. | n = 57; bleach processing plant workers (Southern U.S.). | Slight improvement in safety knowledge, significant decrease in dread, no change in control. |

| SK, SAB | Al-Shabbani [23] | To evaluate effectiveness of new, customized, pre-task TBTs regarding impact on safety knowledge and awareness among highway maintenance workers. | Quasi-experimental, with mixed methods; pre- and post-intervention knowledge assessments and observational recordings. | n = 150 (16 highway maintenance crews) (Kentucky). | Safety knowledge improved by 22%; safer behavior likelihood increased by 33.2% when pre-task TBT was used. |

| SK, SAB | Eggerth et al. [15] | To evaluate retention of knowledge and workplace safety among small construction companies using standard vs. narrative- and question-based TBTs. | Quasi-randomized; pre- and post-training impact surveys. | n = 351 (at baseline); 9 small construction companies and 16 worksites (Ohio). | Narrative-based and discussion questions increased TBT effectiveness in knowledge retention and training impact, no significant change in safety climate. |

| SK, SAB | Rovai et al. [24] | To evaluate increased understanding of safe work practices and personal safety following culturally appropriate TBT educational program among Spanish-speaking dairy workers. | Quasi-experimental with observational component over a 10-week study period. | n = 120; Latino dairy workers (California). | Improvements in worker knowledge, awareness of task-specific hazards, and confidence in abilities to perform job. Positive changes reported by employers in workers’ attitudes, practices, and performance [23]. |

| SK, SAB | Olson et al. [14] | To evaluate different components of new TBT featuring new materials including (i) line drawings and structured safety messages; (ii) worker reactions and desirability of new TBT vs. traditional full-length investigation reports. | Quasi-experimental with interactive, participatory approach. | (i) n = 30; construction supervisors/workers. (ii) Eight construction crews (Greater Portland, Oregon). | (i) Enhanced hazard identification accuracy with line drawings over photos and (ii) preference over short, brief TBT materials. Stronger intentions to engage in preventative measures and behavior noted. |

| SK, SAB | Harrington et al. [25] | To assess the effectiveness (frequency and quality) of a state-wide, multi-faceted, “training-of-trainers” tailgate program among key construction personnel (e.g., supervisors, safety directors, union reps). | Quasi-experimental; mixed methods with formative and process evaluations given at 6 months post-training (3-year study period). | n = 1195; construction workers at multiple sites (California). | Overall, 86% (n = 832) of those trained found TBTs very helpful, with “how to conduct a TBT” being the most useful thing learned. Increased training frequency found for 77% of contractors (n = 84). |

| SK, SAB, SB | Kaskutas et al. [11] | To assess tailored, site-specific TBTs for (i) increased frequency, delivery, and effectiveness of fall prevention and communication training for residential carpentry foremen; and (ii) integration of ergonomics into standard TBT program among construction trade workers. | Quasi-experimental, longitudinal; participatory training with pre- and post-intervention surveys at 6, 12, and 24 weeks. Likert-type, level-of-agreement survey on TBT topics/content and delivery method. | (i) n = 86 construction foremen; n = 273 control. (ii) n = 36 construction workers (Greater St. Louis area, Missouri). | (i) Increased frequency and improvement in delivery and effectiveness of TBTs. (ii) Increased awareness of work methods; observed changes in workers’ ergonomic safety behavior. |

| SK, SAB, SB | Kaskutas et al. [9] | To evaluate feasibility and impact of fall prevention and communication training program among construction foremen. | Quasi-experimental, mixed methods; 8 h training. | n = 29 observational audits; n = 97 construction foremen/crewmember surveys (St. Louis, Missouri). | Increased TBT frequency and improved safety communication; safer behaviors and enhanced fall prevention awareness. |

| SK, SAB, SB | Kaskutas et al. [12] | To assess improvements in safety communication skills and reduce unsafe behaviors among construction crews following intervention. | Quasi-experimental, mixed methods; 8 h training program covering fall prevention, communication strategies, and safety audits. | Residential contractor, n = 17 construction foremen; 2 managers who supervised foremen (Midwest). | Increased use of daily TBTs (from 13% to 68%) observed among foremen. Use of fall protection (PFAS) increased; unsafe behaviors decreased significantly. |

| SK, SB | Brnich et al. [26] | To assess knowledge and awareness following the use of 5–7 min training videos and TBTs as teaching tools among a group of mining workers. | Quasi-experimental; pre- and post-study questionnaires assessing levels of knowledge and awareness on OSH emergency communication topics. | n = N/S (mining workers) (Colorado). | Significant increases in post-training scores in knowledge and awareness; slight increase in awareness observed among older, more experienced miners. |

| SK, SB, HO | Caban- Martinez et al. [27] | To evaluate worker knowledge and N95 respirator use among silica workers following the use of interactive educational TBTs. | Quasi-randomized with pre- and post-assessments and focus groups. | n = 248 construction workers across 5 job sites (Florida). | Increased worker baseline knowledge, practice, and health outcomes post-TBT intervention; 65% increase in use of N95 respirator among experimental group vs. 33% in control group. |

| SB | Rice et al., [28] | To evaluate whether sending safety TBTs about workplace fatalities to construction supervisors by mobile phone would increase their compliance with regulatory standard for conducting at least one safety meeting each month. | Quasi experimental; pre/post-impact surveys. | n = 56; construction supervisors (Oregon). | Compliance increased by 19.39%; no significant change in communication quality or performance. |

| SB, SAB | Sparer et al. [29] | To evaluate the integration of a safety communication and recognition program using a redesigned TBT among multiple construction trade groups. | Quasi-experimental; over a 2-month period. | n = 30 construction workers at 1 job site (Boston, Massachusetts). | Enhanced safety climate and communication; barriers in subcontractor scoring noted. |

| SB, SAB, HO | Kaskutas et al. [12] | To evaluate foremen’s ability to train construction crews in designing/delivering TBTs on fall prevention and safety communication when working at heights. | Quasi-experimental; participatory, 8 h fall prevention and communication training; pre- and post-intervention impact surveys and audits. | n = 84 construction foremen; n = 235 crew members pre-intervention, n = 250 post-intervention, and n = 93 at follow-up (Missouri). | Sustained improvement in fall prevention behaviors and safety communication; predicted 16.6% reduction in self-reported falls. |

| Effectiveness Category | (n) | (%) | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Safety Knowledge (SK) | 11 | 79% | Reed et al. [22]. Al-Shabbani et al. [30]. Eggerth et al. [15]. Rovai et al. [24]. Olson et al. [13]. Harrington et al. [25]. Kaskutas et al. [9,11,12]. Brnich et al. [26]. Caban-Martinez et al. [27]. |

| Safety Attitudes and Beliefs (SAB) | 11 | 79% | Reed et al. [22]. Al-Shabbani et al. [23] Eggerth et al. [15]. Rovai et al. [24]. Olson et al. [13,24]. Harrington et al. [25]. Kaskutas et al. [9,11,12]. Sparer et al. [29] |

| Safety Behavior (SB) | 8 | 57% | Brnich et al. [26]. Caban-Martinez et al. [27]. Rice et al. [28]. Sparer et al. [29]. Kaskutas et al. [9,11,12] |

| Health Outcomes (HO) | 2 | 14% | Kaskutas et al. [11]. Caban-Martinez et al. [27] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kearney, G.D.; Hisel, J.; Staley, J.A. Effectiveness of Toolbox Talks as a Workplace Safety Intervention in the United States: A Scoping Review. Safety 2025, 11, 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11020035

Kearney GD, Hisel J, Staley JA. Effectiveness of Toolbox Talks as a Workplace Safety Intervention in the United States: A Scoping Review. Safety. 2025; 11(2):35. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11020035

Chicago/Turabian StyleKearney, Gregory D., Jamie Hisel, and John A. Staley. 2025. "Effectiveness of Toolbox Talks as a Workplace Safety Intervention in the United States: A Scoping Review" Safety 11, no. 2: 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11020035

APA StyleKearney, G. D., Hisel, J., & Staley, J. A. (2025). Effectiveness of Toolbox Talks as a Workplace Safety Intervention in the United States: A Scoping Review. Safety, 11(2), 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11020035