1. Introduction

Humans—or animals in general—have a visual system endowed with attentional mechanisms. These mechanisms allow the human visual system (HVS) to select from the large amount of information received that which is relevant and to process in detail only the relevant aspects [

1]. This phenomenon is called visual attention. This mobilization of resources for the processing of only a part of whole information allows its rapid processing. Thus the gaze is quickly directed towards certain objects of interest. For living beings, this can sometimes be vital as they can decide whether they are facing prey or a predator [

2].

Visual attention is carried out in two ways, namely

bottom-up attention and

top-down attention [

3].

Bottom-up attention is a process which is fast, automatic, involuntary and directed by the image properties almost exclusively [

1]. The

top-down attention is a slower, voluntary mechanism directed by cognitive phenomena such as knowledge, expectations, rewards, and current goals [

4]. In this work, we focus on the

bottom-up attentional mechanism which is image-based.

Visual attention has been the subject of several research works in the fields of cognitive psychology [

5,

6] and neuroscience [

7], to name a few. Computer vision researchers have also used the advances in cognitive psychology and neuroscience to set up computational visual saliency models that exploit this ability of the human visual system to quickly and efficiently understand an image or a scene. Thus, many computational visual saliency models have been proposed and are mainly subdivided into two categories: conventional models (e.g., Yan et al. model [

8]) and deep learning models (e.g., Gupta et al. model [

9]). For more details, most of the models can be found in these works [

10,

11,

12]).

Computational visual saliency models have several applications such as image/video compression [

13], image correction [

14], iconography artwork analysis [

15], image retrieval [

16], advertisements optimization [

17], aesthetics assessment [

18], image quality assessment [

19], image retargeting [

20], image montage [

21], image collage [

22], object recognition, tracking, and detection [

23], to name but a few.

Computational visual saliency models are oriented to either eye fixation prediction or salient object segmentation or detection. The latter is the subject of this work. Salient object detection is materialized with saliency maps. A saliency map is represented by a grayscale image in which an image region must be whiter as it differs significantly from the rest of the image in terms of shape, set of shapes with a color, mixture of colors, movement, or a discriminating texture or generally any attribute perceived by the human visual system.

Herein, we propose a simple and nearly parameter-free model which gives us an efficient saliency map for a natural image using a new strategy. The proposed model, contrary to classical salient detection methods, uses texture and color features in a way that integrates color in texture features using simple and efficient algorithms. Indeed, the

texture is a ubiquitous phenomenon in natural images: images of mountains, trees, bushes, grass, sky, lakes, roads, buildings, and so forth appear as different types of texture (Haidekker [

24] argues that

texture and shape analysis are very powerful tools for extracting image information in an unsupervised manner. This author adds that the

texture analysis has become a key step in the quantitative and unsupervised analysis of biomedical images [

24]. Other authors, such as Knutsson and Granlund [

25], Ojala et al. [

26], agree that

texture is an important feature for scene analysis of images. Knutsson and Granlund also claim that the presence of a

texture somewhere in an image is more a rule than an exception. Thus,

texture in the image has been shown to be of great importance for image segmentation, interpretation of scenes [

27], in face recognition, facial expression recognition, face authentication, gender recognition, gait recognition and age estimation, to just name a few [

28]). In addition, natural images are usually also color images and it is then important to take this factor into account as well. In our application, the color is taken into account and integrated in an original way,

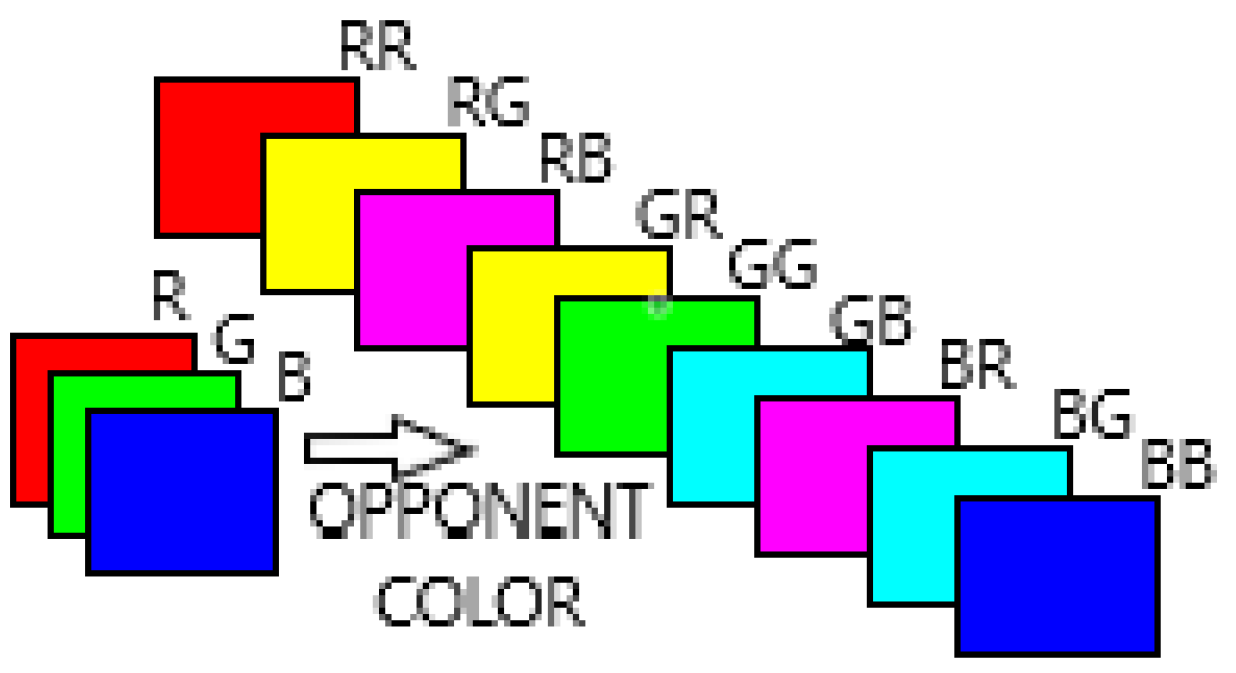

via the extraction of the textural characteristics made on the pairs of opposing color spaces.

Although there is much work relating to

texture, there is no formal definition of

texture [

25]. There is also no agreement on a single technique for measuring texture [

27,

28]. Our model uses the LTP (

local ternary patterns) [

29] texture measurement technique. The LTP (local ternary patterns) is an extension of local binary pattern (LBP) with three code values instead of two for LBP. LBP is known to be a powerful texture descriptor [

28,

30]. Its main qualities are invariance against monotonic gray level changes and computational simplicity and its drawback is that it is sensitive to noise in uniform regions of the image. In contrast, LTP is more discriminant and less sensitive to noise in uniform regions. The LTP (

Local Ternary Patterns) is therefore better suited to tackle our salience detection problem. Certainly, the presence in natural images of several patterns make the detection of salient objects complex. However, the model we propose does not just focus on the patterns in the image by processing them separately from the colors as most models do [

31,

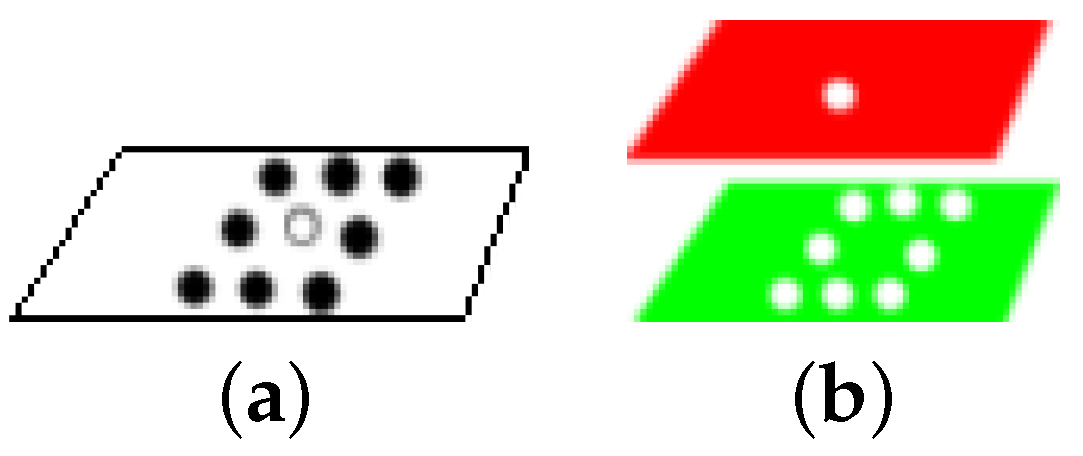

32] but it takes into account both the presence in natural images of several patterns and color, not separately. This task of integrating color in texture features is accomplished through LTP (Local Ternary Patterns) applied to opposing color pairs of a given color space. The LTP describes the local textural patterns for a grayscale image through a code assigned to each pixel of the image by comparing it with its neighbours. When LTP is applied to an opposing color pair, the principle is similar to that used for a grayscale image. However, for LTP on an opposing color pair, the local textural patterns are obtained thanks to a code assigned to each pixel, but the value of the pixel of the first color of the pair is compared to the equivalents of its neighbours in the second color of the pair. The color is thus integrated to the local textural patterns. In this way, we characterize the color micro-textures of the image without separating the textures in the image and the colors in this same image. The color micro-textures’ boundaries correspond to the superpixel obtained thanks to the SLICO (Simple Linear Iterative Clustering with zero parameter) algorithm [

33] which is faster and exhibits state-of-the-art boundary adherence. We would like to point out that there are other superpixels algorithms that have a good performance such as the AWkS algorithm [

34]; however, we chose SLICO because it is fast and almost parameter-free. A feature vector representing the color micro-texture is obtained by the concatenation of the histograms of the superpixel (defining the micro-texture) of each opposing color pair. Each pixel was then characterized by a vector representing the color micro-texture to which it belongs. We then compared the color micro textures characterizing each pair of pixels of the image being processed thanks to the fast version of the MDS (multi-dimensional scaling) method

FastMap [

35]. This comparison permits us to capture the degree of a pixel’s uniqueness or a pixel’s rarity. The FastMap method will allow this capture while taking into account the non-linearities in the representation of each pixel. Finally, since there is no single color space suitable for color texture analysis [

36], we combined the different maps generated by FastMap from different color spaces (see

Section 3.1), such as RGB, HSL, LUV and CMY, to exploit each other’s strengths in the final saliency map.

Thus, the contribution of this work is twofold:

we propose an unexplored approach to salient object detection. Indeed, our model integrates the color information into the texture whereas most of the models in the literature that use these two visual characteristics, namely color and texture, process them separately thus implicitly considering them as independent characteristics. Our model, on the other hand, allows us to compute saliency maps that take into account the interdependence of color and texture in an image as they are in reality;

we also use the FastMap method which is conceptually both local and global allowing us to have a simple and efficient model whereas most of the models in the literature use either a local approach or a global approach and other models combine these approaches in salient object detection.

Our model highlights the interest in opposing colors for the salient object detection problem. In addition, this model could be combined and be complementary with more classical approaches using the contrast ratio. Moreover, our model can be parallelized (using the massively parallel processing power of GPUs: graphics processing units) by processing each opposing color pair in parallel.

The rest of this work is organized as follows:

Section 2 presents some models related to this approach with an emphasis on the features used and how their dissimilarities are computed.

Section 3 presents our model in detail.

Section 4 describes the datasets used, our experimental results, the impact of the color integration in texture and the comparison of our model with state-of-the-art models.

Section 5 discusses our results but also highlights the strength of our model related to our results.

Section 6 concludes this work.

2. Related Work

Most authors define salient object detection as a capture of the uniqueness, distinctiveness, or rarity of a pixel, a superpixel, a patch, or a region of an image [

11]. The problem of detecting salient objects is therefore to find the best characterization of the pixel, the patch or the superpixel and to find the best way to compare the different pixels (patch or superpixel) representation to obtain the best saliency maps. In this section, we present some models related to this work approach with an emphasis on the features used and how their dissimilarities are computed.

Thanks to studies in cognitive psychology and neuroscience, such as those by Treisman and Gelade [

37], Wolfe et al. [

6,

38] and Koch and Ullman [

7], the authors of the seminal work of Itti et al. [

39]—oriented eye fixation prediction—chose as features: color, intensity and orientation. Frintrop et al. [

40], adapting the Itti et al. model [

39] for salient objects segmentation—or detection—chose color and intensity as features. In the two latter models, the authors used pyramids of Gaussian and center-surround differences to capture the distinctiveness of pixels.

The Achanta et al. model [

41] and the histogram-based contrast (HC) model [

42] used color in CIELab space to characterize a pixel. In the latter model, the pixel’s saliency is obtained using its color contrast to all other pixels in the image by measuring the distance between the pixel for which they are computing saliency and all other pixels in the image; this is coupled with a smoothing procedure to reduce quantization artifacts. The Achanta et al. model [

41] computed a pixel’s saliency on three scales. For each scale, this saliency is computed as the Euclidean distance between the average color vectors of the inner region

and that of the outer region

, both centered on that pixel mentioned above.

Joseph and Olugbara [

43] used color histogram clustering to determine suitable homogeneous regions in image and compute each region saliency based on color contrast, spatial features, and center prior.

Guo and Zhang [

44], in the phase spectrum of the Quaternion Fourier Transform model, represent each image’s pixel by a Quaternion that consists of color, intensity and a motion feature. A Quaternion Fourier Transform (QFT) is then applied to that representation of each pixel. After setting the module of the result of the QFT to 1 to keep only the phase spectrum in the frequency domain, this result is used to reconstruct the Quaternion in spatial space. The module of this reconstructed Quaternion is smoothed with a Gaussian filter and this then produces the spatio-temporal saliency map of their model. For static images the motion feature is set to zero.

Other models also take color and position as features to characterize a region or patch instead of a pixel [

42,

45,

46]. They differ, however, in how they obtain the salience of a region or patch. Thus, the region-based contrast (RC) model [

42] measured the region saliency as the contrast between this region and the other regions of the image. This contrast is also weighted depending on the spatial distance of this region relative to the other regions of the image.

In the Perazzi et al. model [

45], contrast is measured by the uniqueness rate and the spatial distribution of small perceptually homogeneous regions. The uniqueness of a region is calculated as the sum of the Euclidean distances between its color and the color of each region weighted by a Gaussian function of their relative position. The spatial distribution of a region is given by the sum of the Euclidean distances between its position and the position of each region weighted by a Gaussian function of their relative color. The region saliency is a combination of its uniqueness and its spatial distribution. Finally, the saliency of each pixel in the image is a linear combination of the saliency of homogeneous regions. The weight for each region’s saliency of this sum is a Gaussian function of the Euclidean distances between the color of the pixel and the colors of the homogeneous regions and the Euclidean distances between its spatial position and theirs. In the Goferman et al. model [

46], the dissimilarity between two patches is defined as directly proportional to the Euclidean distance between the colors of the two patches and inversely proportional to their relative position normalized to be between 0 and 1. The salience of a pixel at a given scale is then 1 minus the inverse of the exponential of the mean of the dissimilarity between the patch centered on this pixel and the patches which are more similar to it; the final saliency of the pixel being the average of the saliency of the different scales to which they add the context.

Some models focus on the patterns as features but they compute patterns separately from colors [

31,

32]. For example Margolin et al. [

31] defined a salient object as consisting of pixels whose local neighborhood (region or patch) is distinctive in both color and pattern. The final saliency of their model is the product of the color and pattern distinctness weighted by a Gaussian to add a center-prior.

As Frintrop et al. [

40] stated, most saliency systems use intensity and color features. They are differentiated by the feature extraction and the general structure of the models. They have in common the computation of the contrast relative to the features chosen since the salient objects are so because of the importance of their dissimilarities with their environment. However, models in the literature differ on how these dissimilarities are obtained. Even though there are many salient object detection models, the detection of salient objects remains a challenge [

47].

The contribution of this work is twofold:

we propose an unexplored approach to the detection of salient objects. Indeed, we use for the first time in the salient object detection, to our knowledge, the feature color micro-texture in which the color feature is integrated algorithmically into the local textural patterns for salient object detection. This is done by applying LTP (Local Ternary Patterns) to each of the opposing color pairs of a chosen color space. Thus, in salient object detection computation, we integrate the color information in the texture while most of the models in the literature which use these two visual features, namely color and texture, perform this computation separately;

we also use the FastMap method which, conceptually, is both local and global while most of the models in the literature use either a local approach or a global approach and other models combine these approaches in saliency detection. FastMap can be seen as a nonlinear one-dimensional reduction of the micro-texture vector taken locally around each pixel with the interesting constraint that the (Euclidean) difference existing between each pair of (color) micro textural vectors (therefore centered on two pixels of the original image) is preserved in the reduced (one-dimensional) image and is represented (after reduction) by two gray levels separated by this same distance. After normalization, a saliency measure map (with range values between 0 and 1) is estimated in which lighter regions are more salient (higher relevance weight) and darker regions are less salient.

Most of the models in the literature use either a local approach or a global approach and other models combine these approaches in saliency detection.

The model we propose in this work is both simple and efficient while being almost parameter free. Being simple and being different from the classic salience detection models which use the color contrast strategy between a region and other regions of an image, our model could therefore be effectively combined with these models for a better performance. Moreover, by processing each opposing color pair in parallel, our model can be parallelized using the massively parallel processing power of GPUs (graphics processing units). In addition, it produces good results in comparison with the state-of-the-art models in [

48] for the ECSSD, MSRA10K, DUT-OMRON, THUR15K and SED2 datasets.

4. Experimental Results

In this section, we present our salient object detection model’s results. In order to obtain the LTP

pixel’s code (LTP code for simplification), we used an adaptive threshold. For a pixel at position

with value

, the threshold for its LTP code is a tenth of the pixel’s value:

(see Equation (

2)). We chose this threshold because empirically it is this value that has given better results. The number of neighbors P around the pixel on a radius R used to find its LTP code in our model is

and

. Thus the maximum value of the LTP code in our case is

. This makes the maximum size of the histogram characterizing the micro-texture in an opposing color pair to be

which is then requantized with levels/classes of 75 bins (see

Section 3.2). The superpixels that we use as adaptive windows to characterize the color micro-textures are obtained thanks to the SLICO (Simple Linear Iterative Clustering with zero parameter) algorithm which is faster and exhibits state-of-the-art boundary adherence. Its only parameter is the number of superpixels desired and is set to 100 in our model (which is also the value recommended by the author of the SLICO algorithm). Finally, we use in the combination to obtain the final saliency map, the color spaces RGB, HSL, LUV and CMY.

We chose, for our experiments, images from public datasets, the most widely used in the salient object detection field [

48] such as Extended Complex Scene Saliency Dataset (ECSSD) [

52], Microsoft Research Asia 10,000 (MSRA10K) [

42,

48], DUT-OMRON (Dalian University of Technology—OMRON Corporation) [

53], THUR15K [

54] and SED2 (Segmentation evaluation database with two salient objects) [

55]. The ECSSD contains 1000 natural images and their ground truth. Many of its images are semantically meaningful, but structurally complex for saliency detection [

52]. The MSRA10K contains 10,000 images and 10,000 manually obtained binary saliency maps corresponding to their ground truth. DUT-OMRON contains 5168 images and their binary mask. THUR15K is a dataset of images taken from the “Flickr” web site divided into five categories (butterfly, coffee mug, dog jump, giraffe, plane), each of which contains 3000 images. Only 6233 images have ground truths. The images of this dataset represent real world scenes and are considered complex for obtaining salient objects [

54]. The SED2 dataset has 100 images and their ground truth.

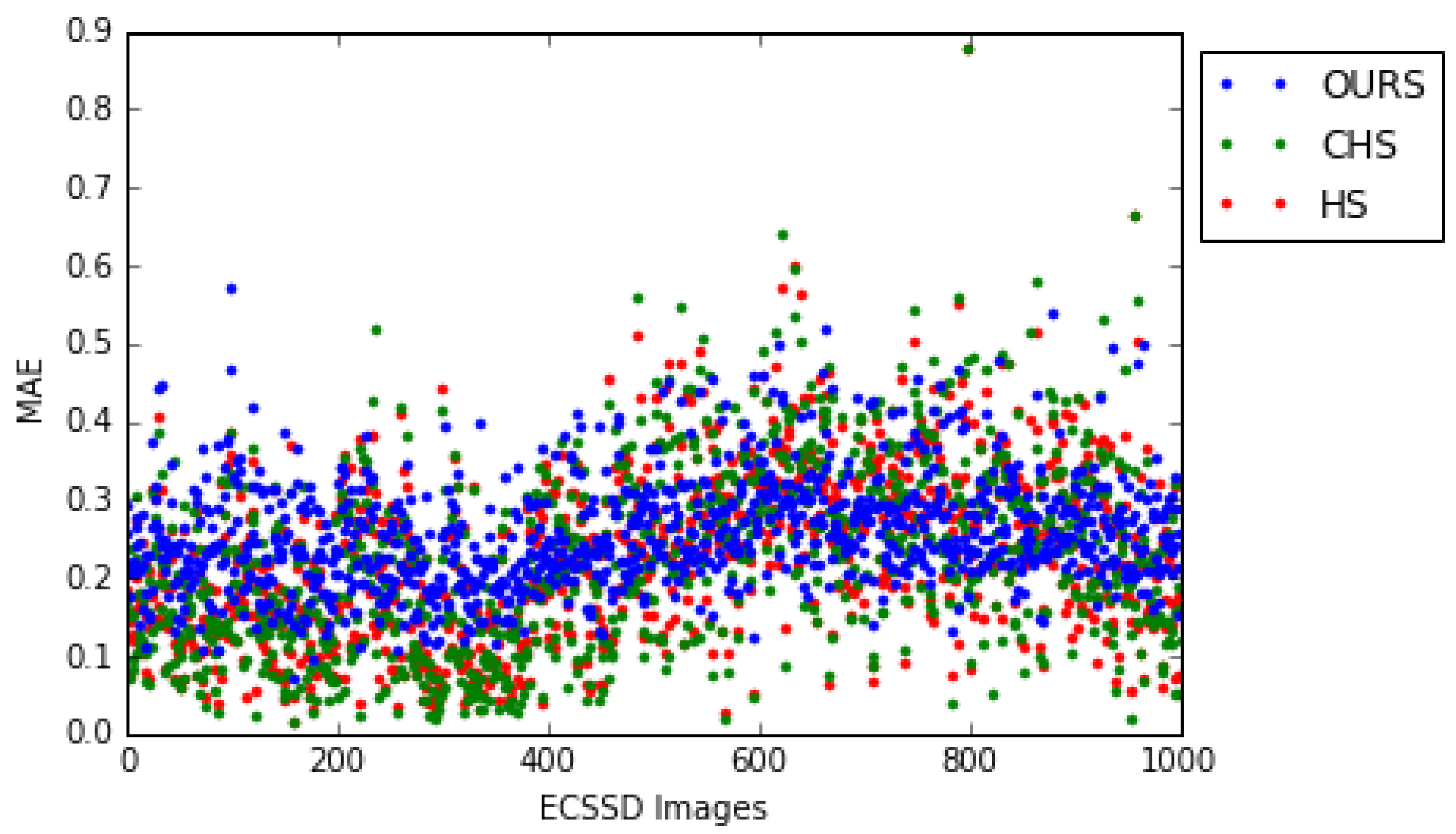

We used for the evaluation of our salient object detection model the Mean Absolute Error (MAE), the Mean Squared Error (MSE), the Precision-Recall curve (PR), the

measure curve and the

measure with

. The MSE measure results for ECSSD, MSRA10K, DUT-OMRON, THUR15K and SED2 datasets are shown in

Table 1. We compared the MAE (Mean Absolute Error) and the

F measure of our model with the 29 state-of-the-art models from Borji et al. [

48] and our model outperformed many of them as shown in

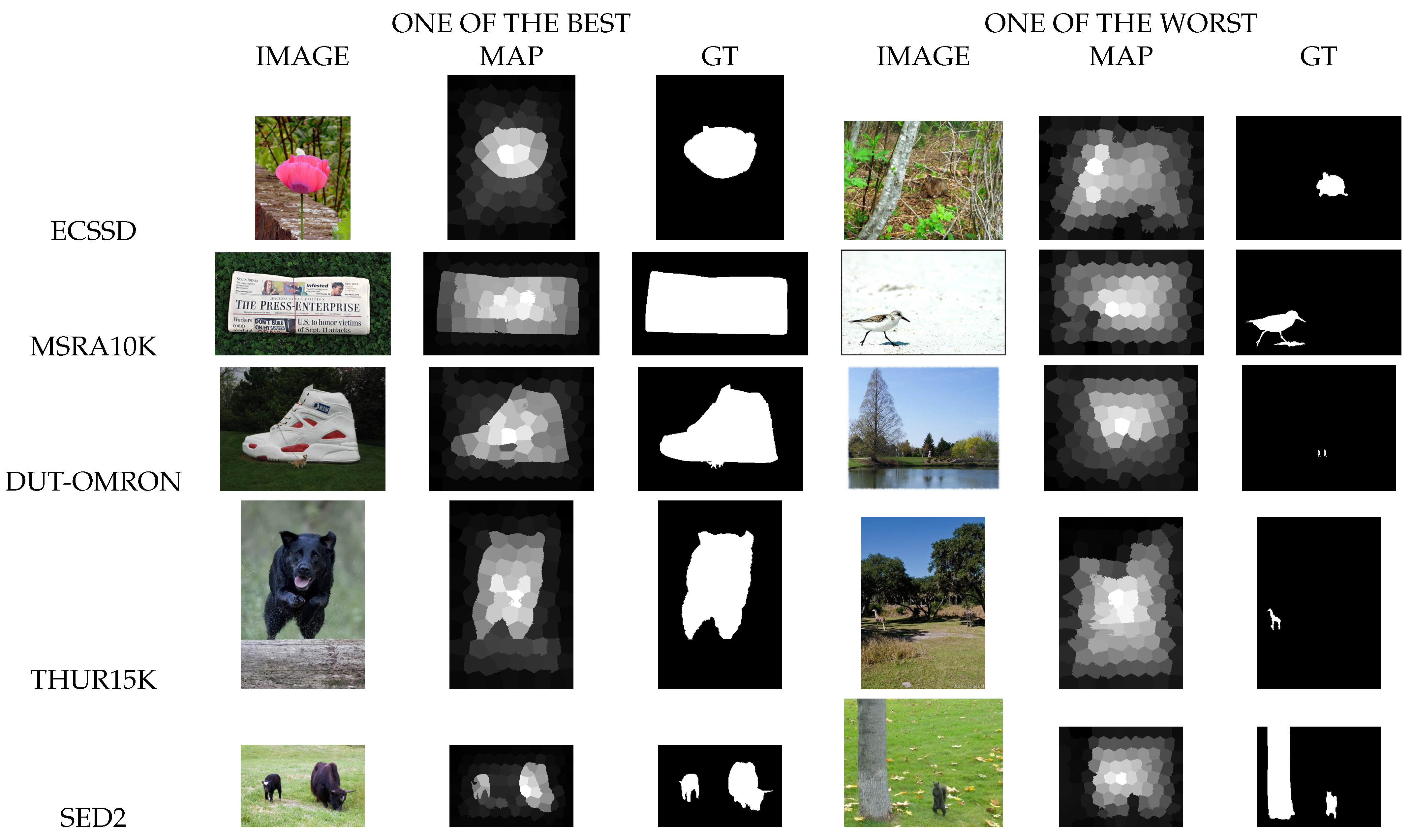

Table 2. In addition, we can see that our model succeeded to obtain saliency maps close to the ground truth for each of the datasets used although for some images it failed, as shown in

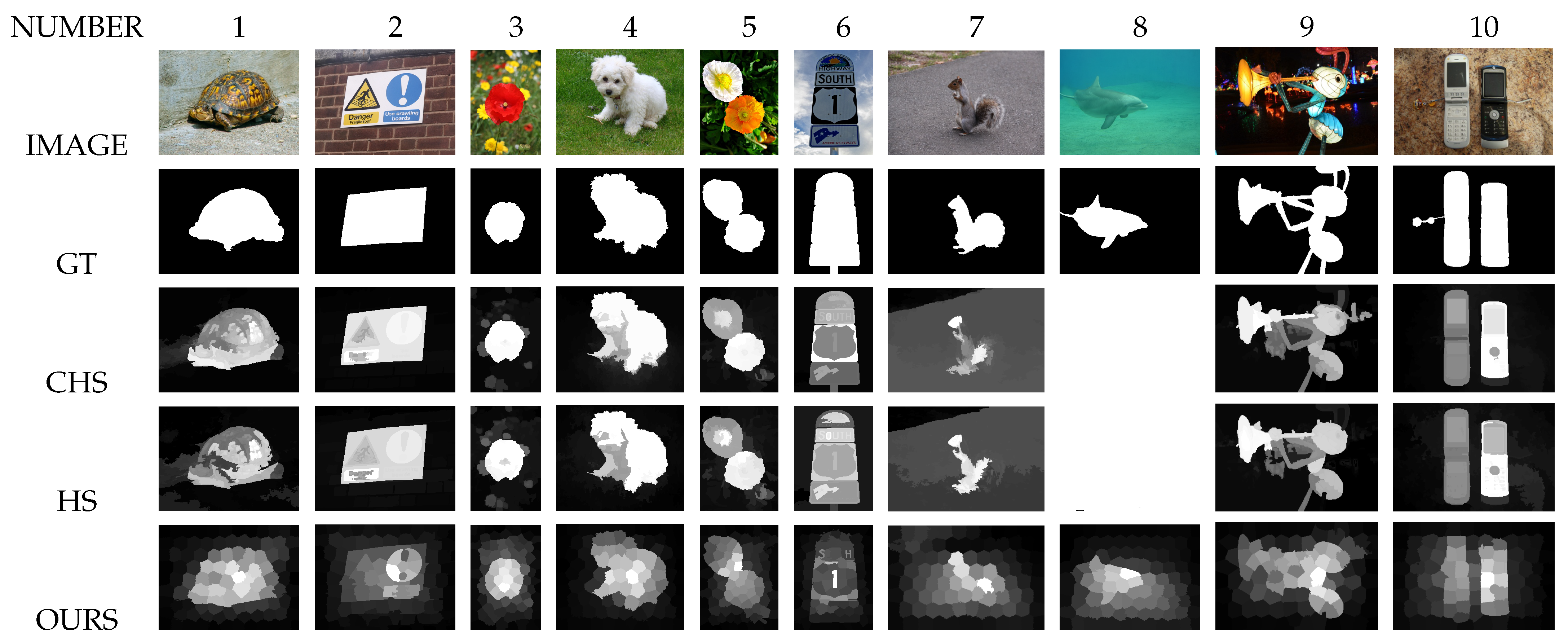

Figure 9.

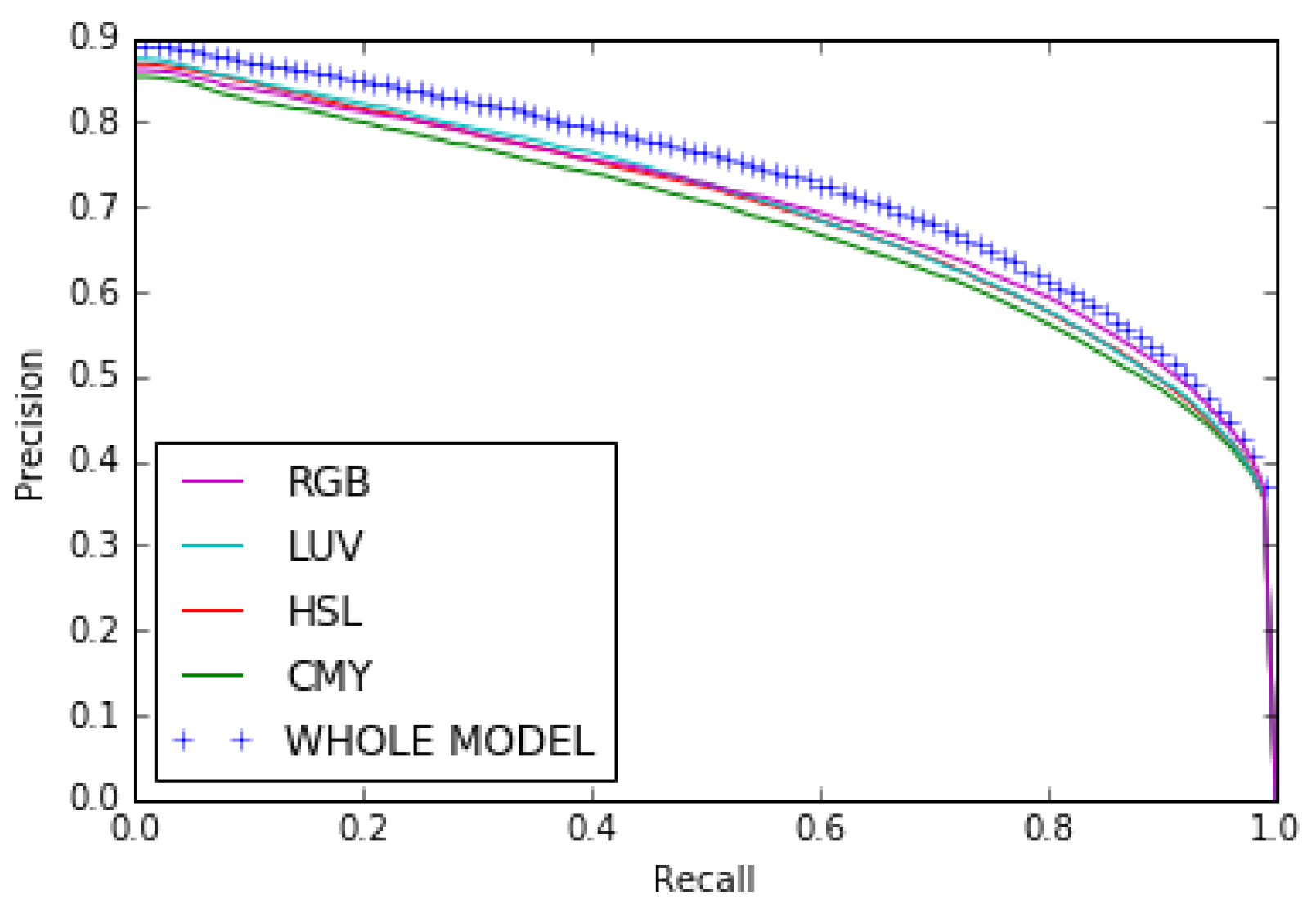

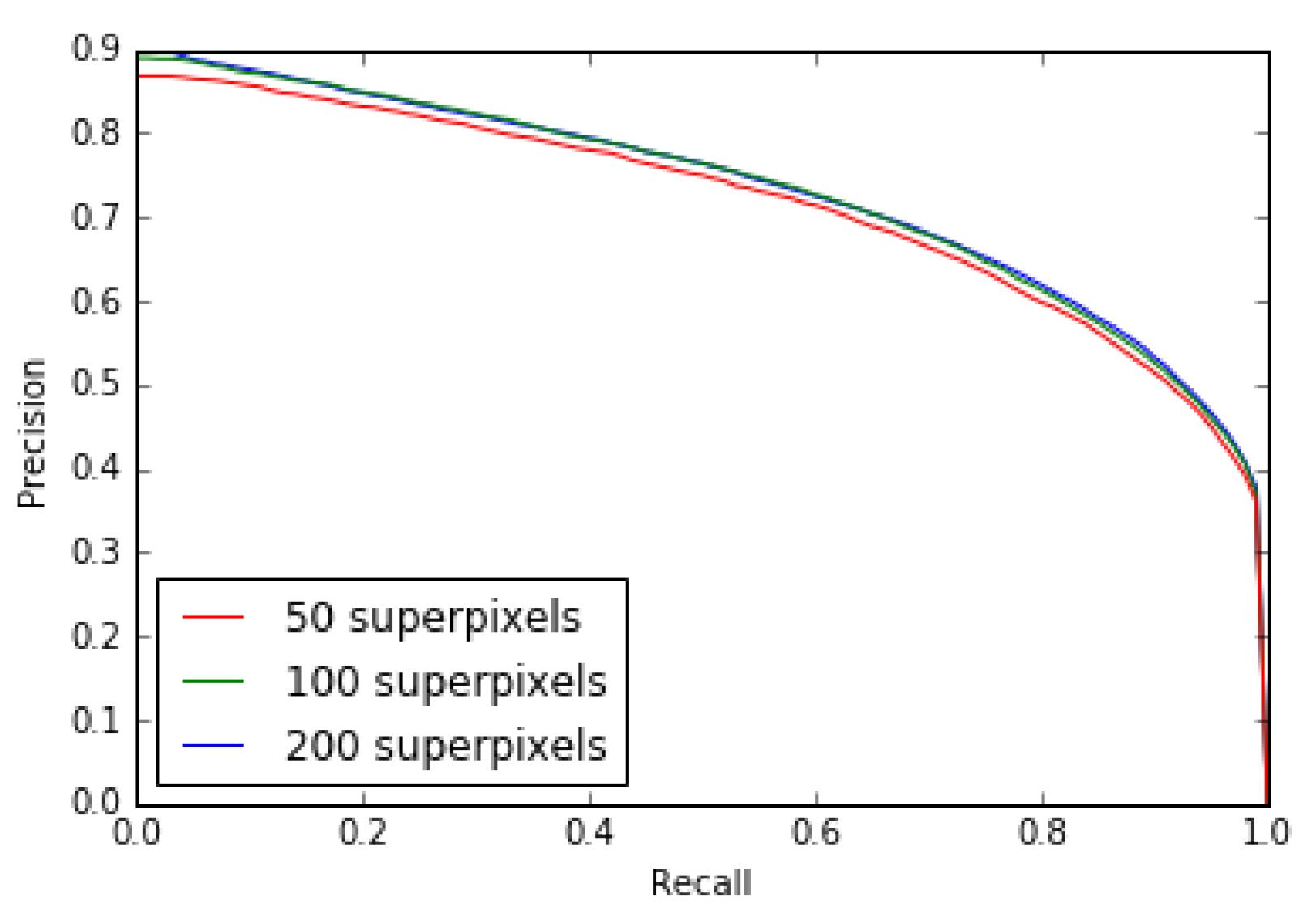

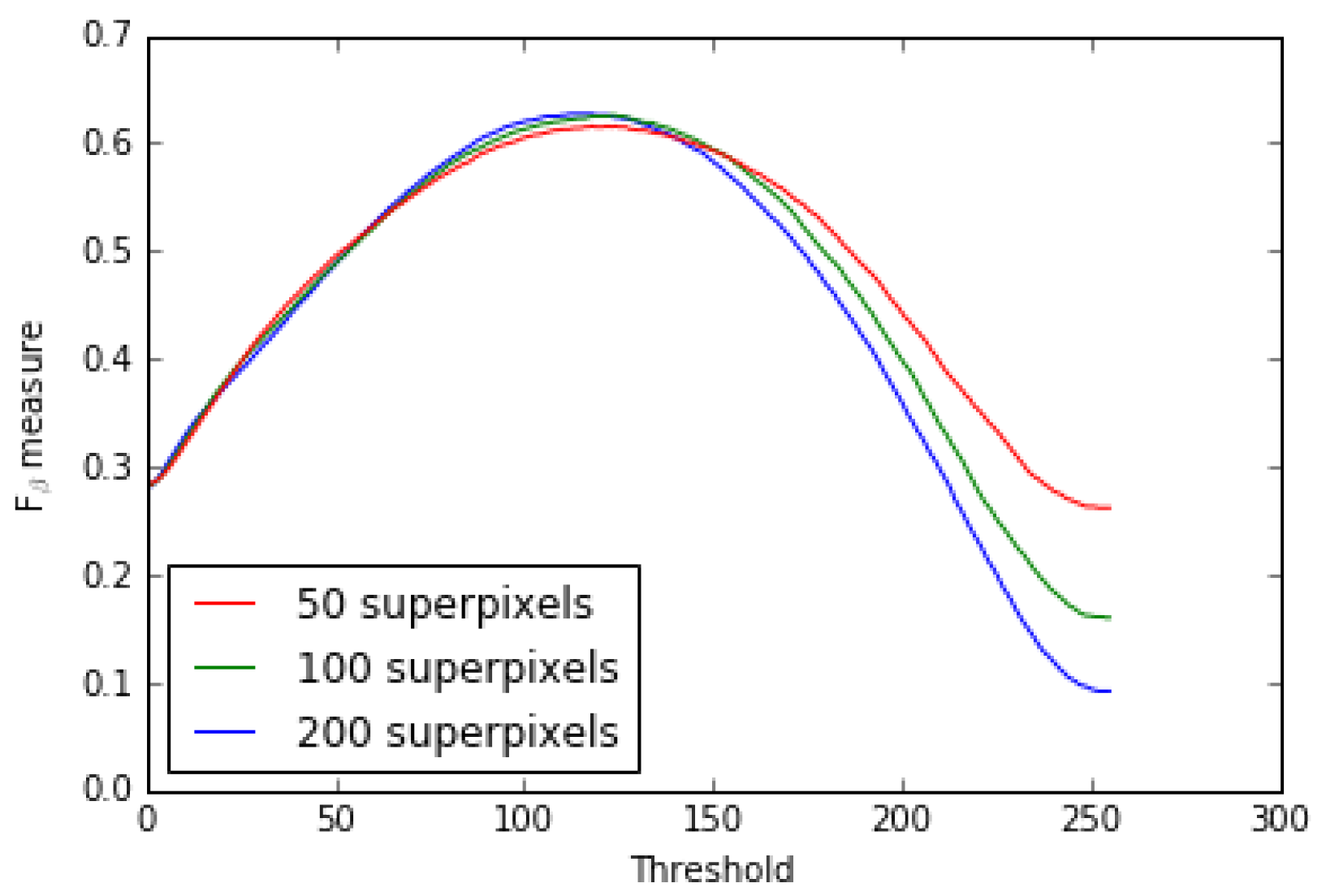

4.1. Color Opposing and Colors Combination Impact

Our results show that combining the opposing color pairs improves the individual contribution of each pair to the

F measure and the Precision-Recall as shown for the RGB color space by the

F measure curve (

Figure 10) and the Precision–Recall curve (

Figure 11). The combination of the color spaces RGB, HSL, LUV and CMY also improves the final result as can be seen from the

measure curve and the precision–recall curve (see

Figure 12 and

Figure 13).

4.2. Comparison with State-of-the-Art Models

In this work, we studied a method that requires no learning basis. Therefore, we did not include machine learning methods in these comparisons.

We compared the MAE (Mean Absolute Error) and

F measure of our model with the 29 state-of-the-art models from Borji et al. [

48] and our model outperformed many of them as shown in

Table 2.

Table 3 shows the

measure and

Table 4 the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) of our model on ECSSD, MSRA10K, DUT-OMRON, THUR15K and SED2 datasets compared to some state-of-the-art models.

Table 2.

Number of models among the 29 state-of-the-art models from Borji et al. [

48] outperformed by our model on MAE and

measure results.

Table 2.

Number of models among the 29 state-of-the-art models from Borji et al. [

48] outperformed by our model on MAE and

measure results.

| | ECSSD | MSRA10K | DUT-OMRON | THUR15K | SED2 |

|---|

| 21 | 11 | 12 | 17 | 4 |

| MAE | 11 | 8 | 6 | 10 | 3 |

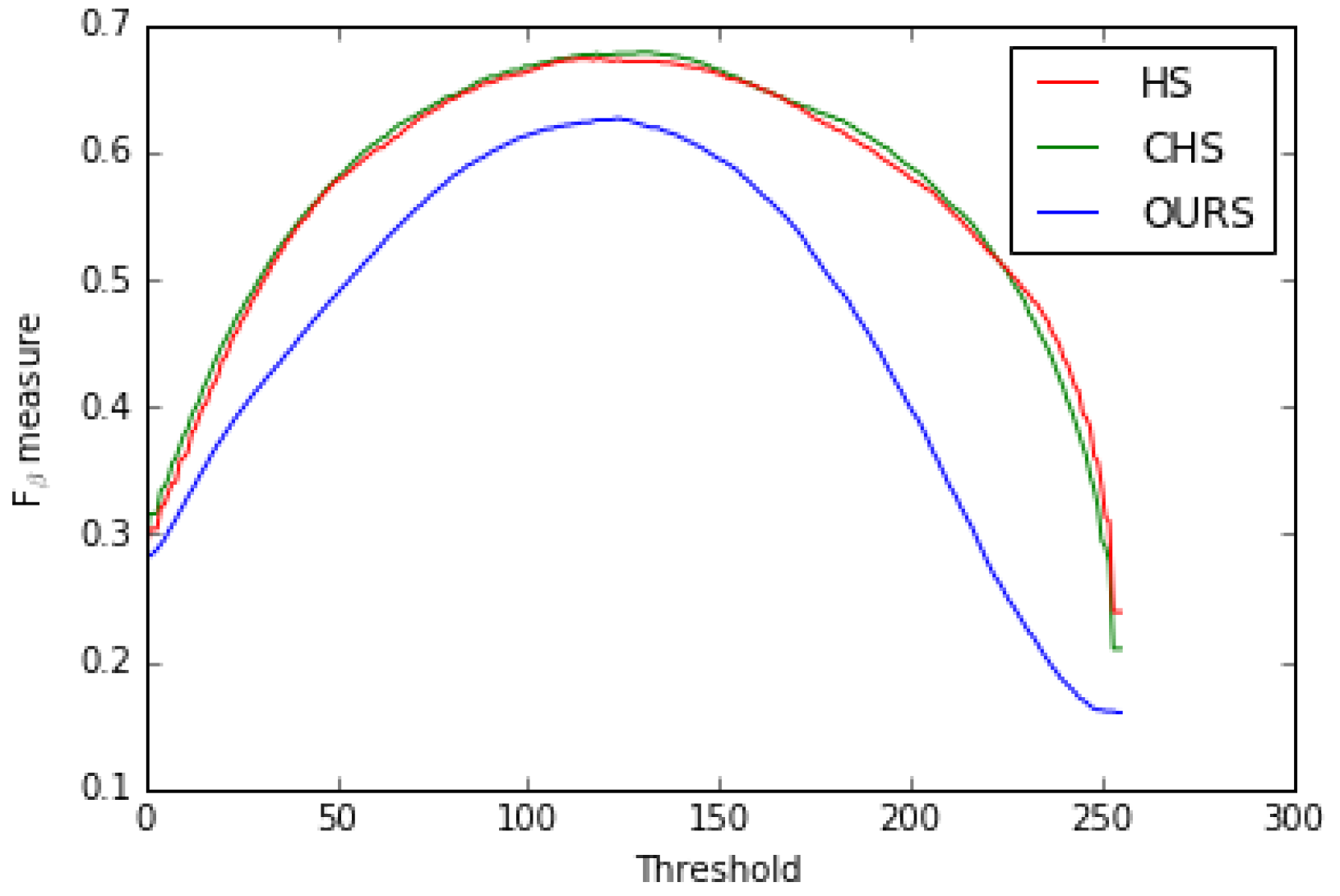

Comparison with Two State-of-the-Art Models HS and CHS

We have chosen to compare our model to HS [

8] and CHS [

52] state-of-the-art models because on the one hand they are among the best state-of-the-art models and on the other hand our model has some similarities with these two models. Indeed, our model is a combination of energy-based models MDS and SLICO and is based on the color texture while the two state-of-the-art models are energy based models. Moreover, their energy function is based on a combination of the color and the pixel coordinates.

First, the visual comparison of some of our saliency maps with those of two state-of-the-art models (“Hierarchical saliency detection”: HS [

8] and “Hierarchical image saliency detection on extended CSSD”: CHS [

52] models) shows that our saliency maps are of good quality (see

Figure 14).

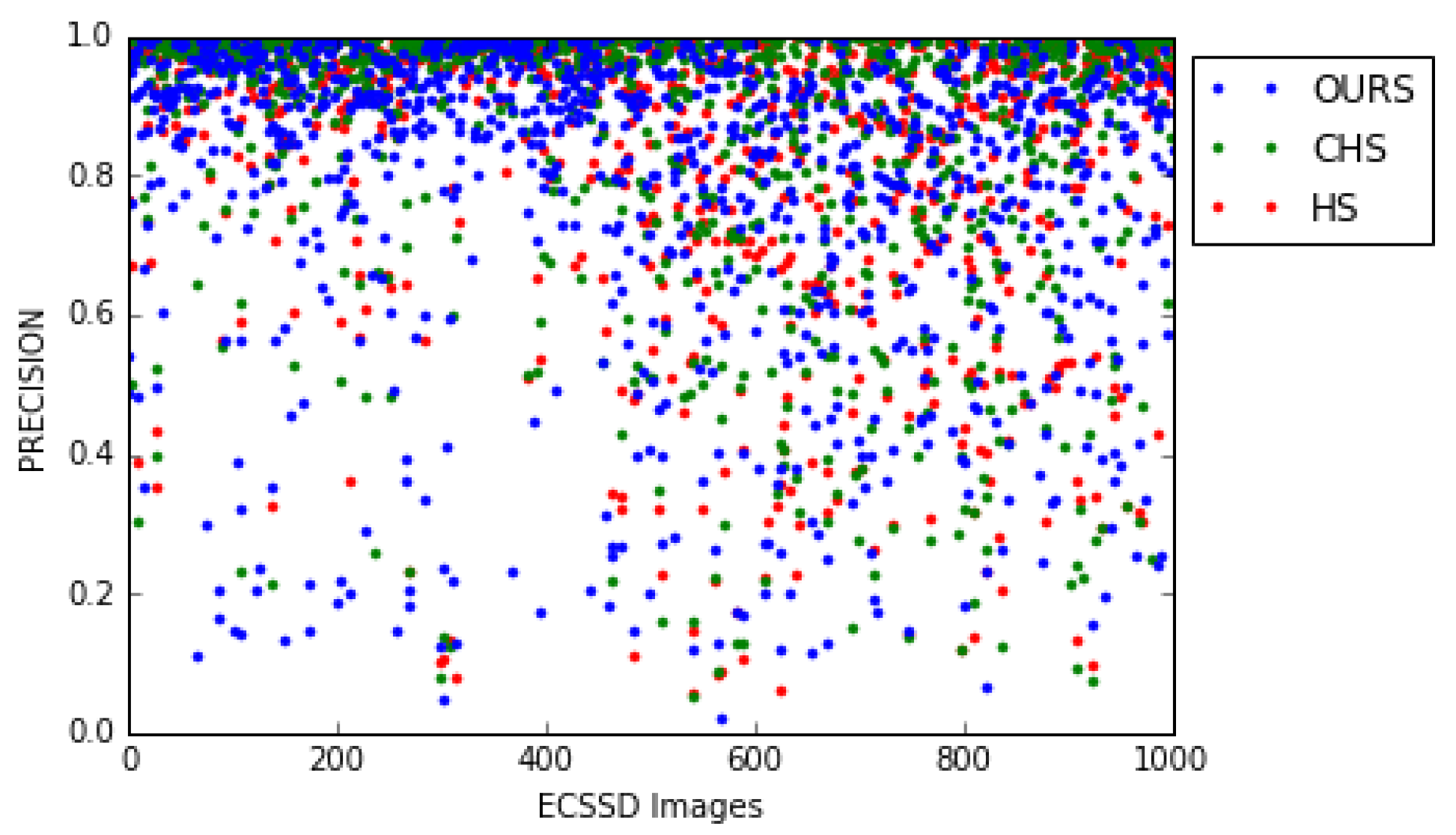

Second, we compared our model with the two state-of-the-art HS [

8] and CHS [

52] models with respect to the precision-recall,

F measure curves (see

Figure 15 and

Figure 16) and MSE (Mean Squared Error).

Table 5 shows that our model outperformed them on the MSE measure.

Thus, our model is better than HS [

8] and CHS [

52] for the MSE measure while both models are better for the

and Precision–Recall.

Our model also outperformed some of the recent methods for

-measure on the ECSSD dataset as shown in

Table 6.

6. Conclusions

In this work, we presented a simple, nearly parameter-free model for the estimation of saliency maps. We tested our model on the complex ECSSD dataset for which the average measures of MAE = and F measure = , and on the MSRA10K dataset. We also tested on THUR15K, which represents real world scenes and is considered complex for obtaining salient objects, and on DUT-OMRON and SED2 datasets.

The novelty of our model is that it only uses the textural feature after incorporating the color information into these textural features thanks to the opposing color pairs theory of a given color space. This is made possible by the LTP (Local Ternary Patterns) texture descriptor which, being an extension of LBP (Local Binary Patterns), inherits its strengths while being less sensitive to noise in uniform regions. Thus, we characterize each pixel of the image by a feature vector given by a color micro-texture obtained thanks to the SLICO superpixel algorithm. In addition, the FastMap algorithm reduces each of these feature vectors to one dimension while taking into account the non-linearities of these vectors and preserving their distances. This means that our saliency map combines local and global approaches in a single approach and does so in almost linear complexity times.

In our model, we used RGB, HSL, LUV and CMY color spaces. Our model is therefore perfectible if we increase the number of color spaces (uncorrelated) to be merged.

As shown by the results we obtained, this strategy generates a model which is very promising, since it is quite different from existing saliency detection methods using the classical color contrast strategy between a region and the other regions of the image and, consequently, it could thus be efficiently combined with these methods for a better performance. Our model can also be parallelized (using the massively parallel processing power of GPUs) by processing each opposing color pair in parallel. In addition, it should be noted that this strategy of integrating color into local textural patterns could also be interesting to study with deep learning techniques or convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to further improve the quality of saliency maps.