Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.R.-S., J.L., and R.Y.; methodology, S.R.-S., J.L., and R.Y.; software, S.R.-S., J.L., and J.Z.; validation, S.R.-S., J.L., and R.Y.; formal analysis, S.R.-S., J.L., and R.Y.; investigation, S.R.-S., J.L., and R.Y.; data curation, S.R.-S. and J.Z.; writing—original draft preparation S.R.-S. and R.Y.; writing—review and editing, J.L. and R.Y.; supervision, J.L.; project administration, J.L.; funding acquisition, J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

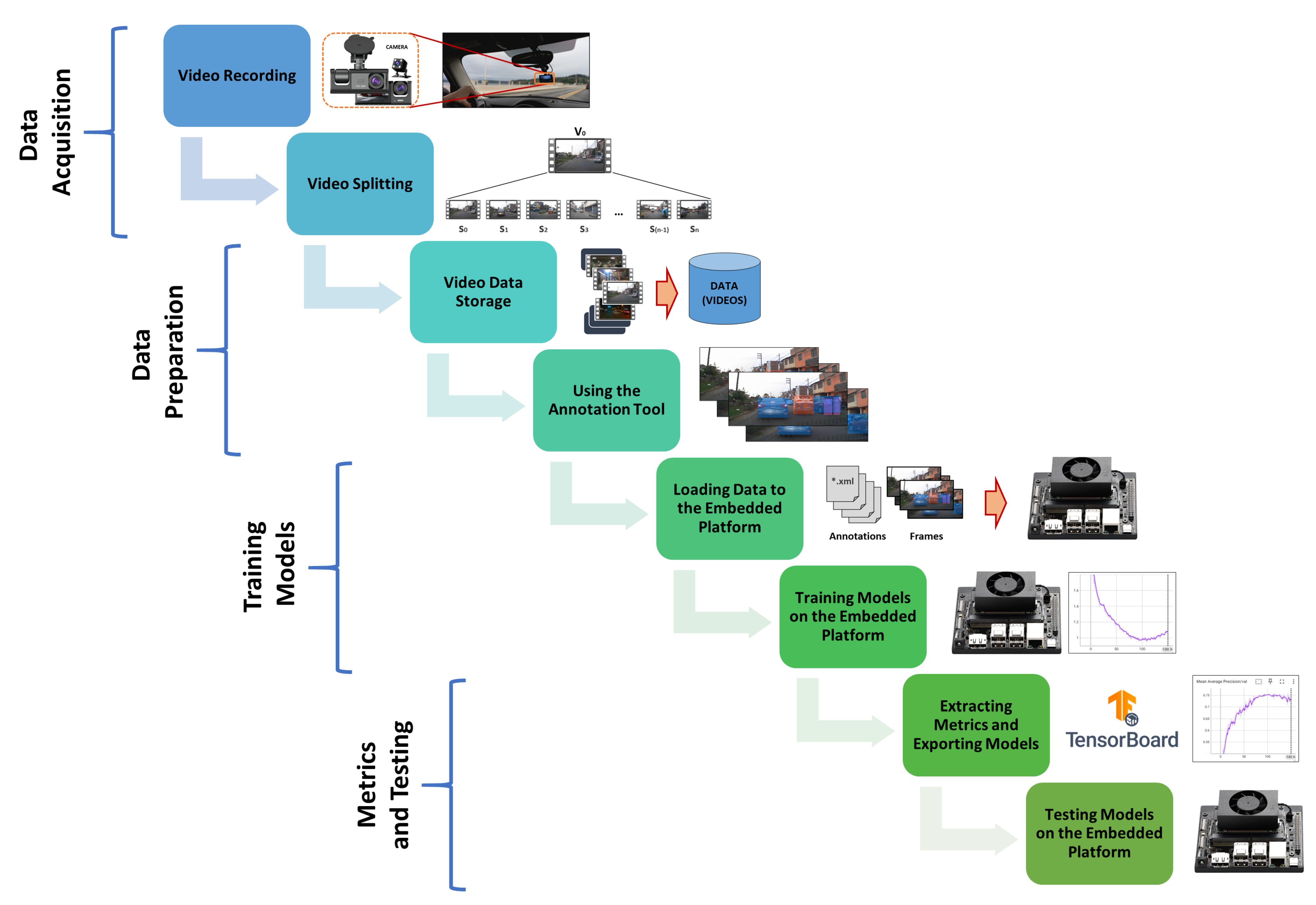

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the implementation used on the embedded platform.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the implementation used on the embedded platform.

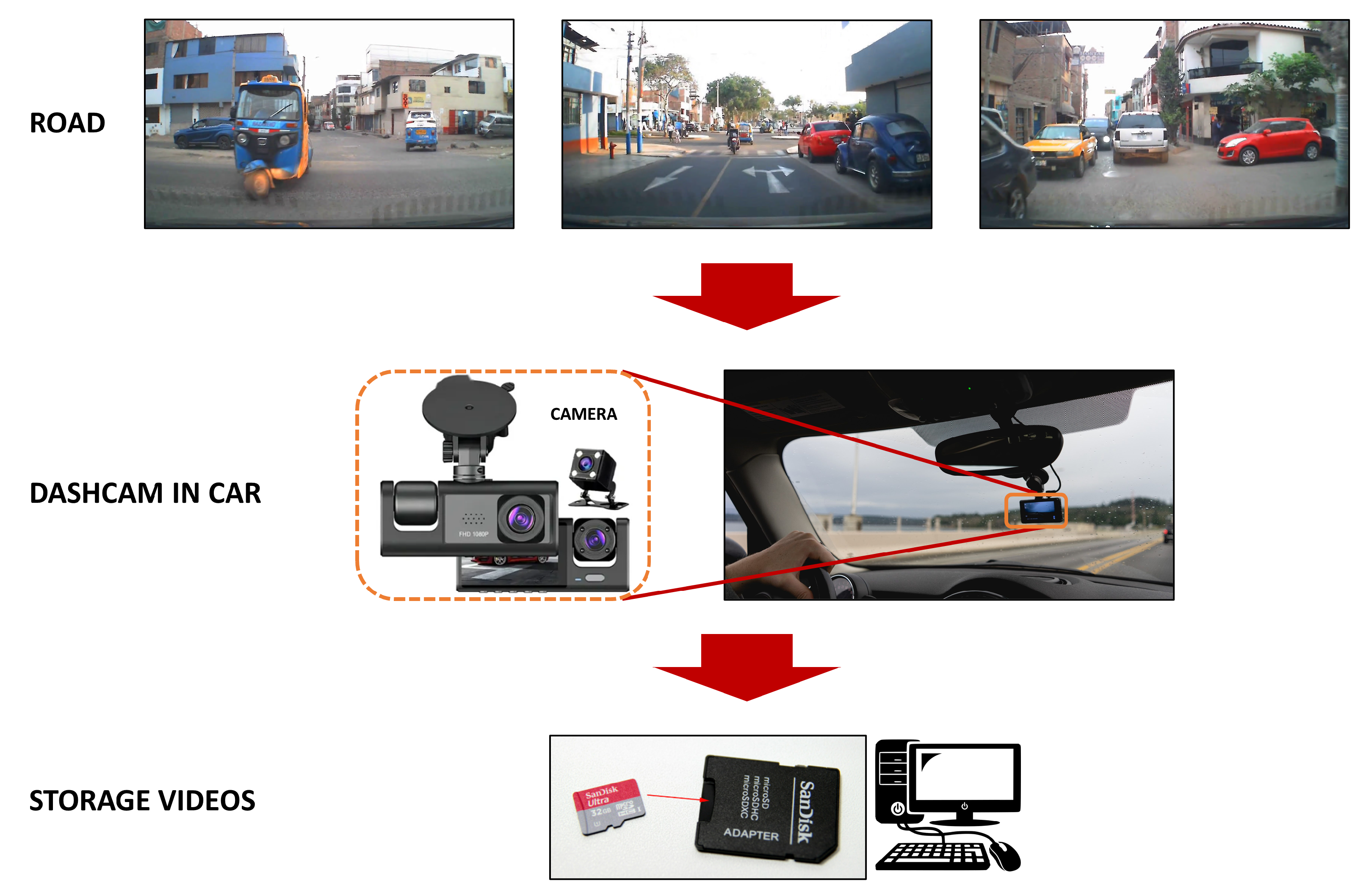

Figure 2.

Diagram to record and store videos from the road.

Figure 2.

Diagram to record and store videos from the road.

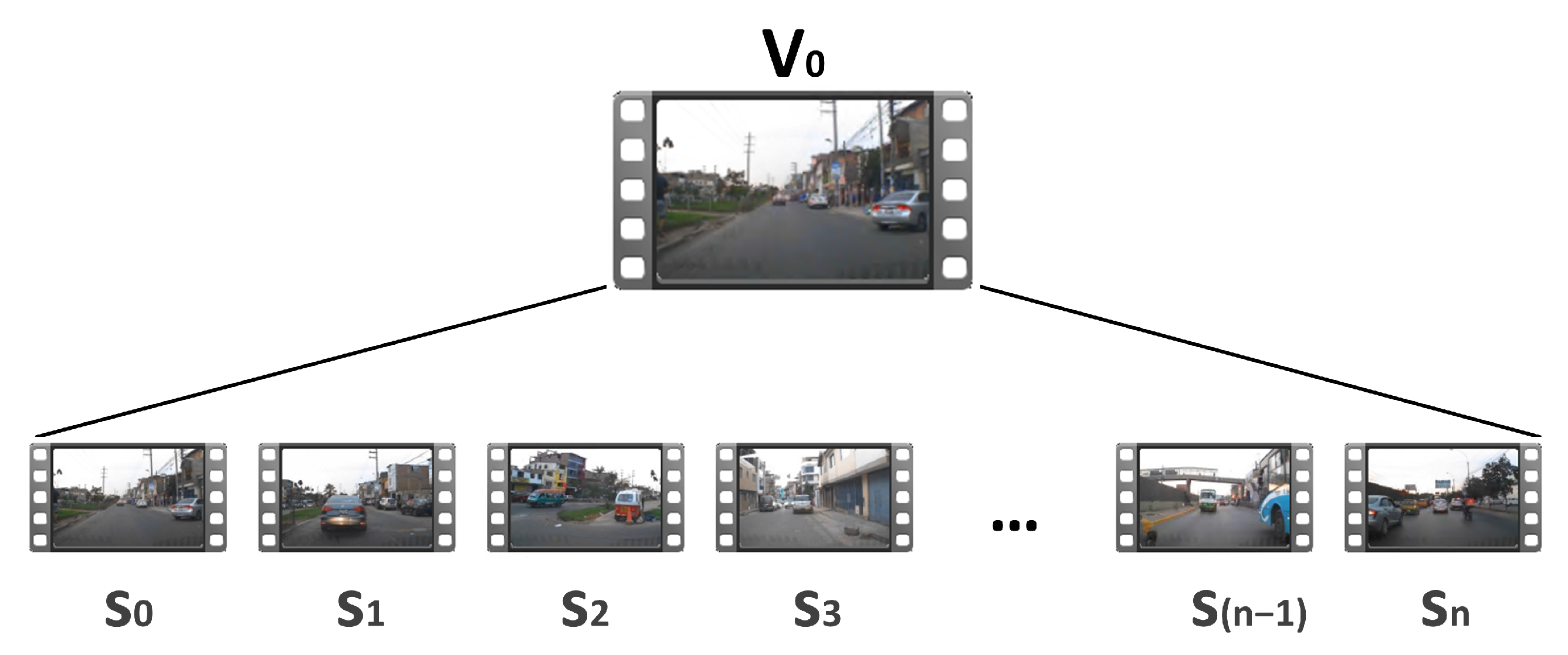

Figure 3.

Segmentation of recorded videos into small segments.

Figure 3.

Segmentation of recorded videos into small segments.

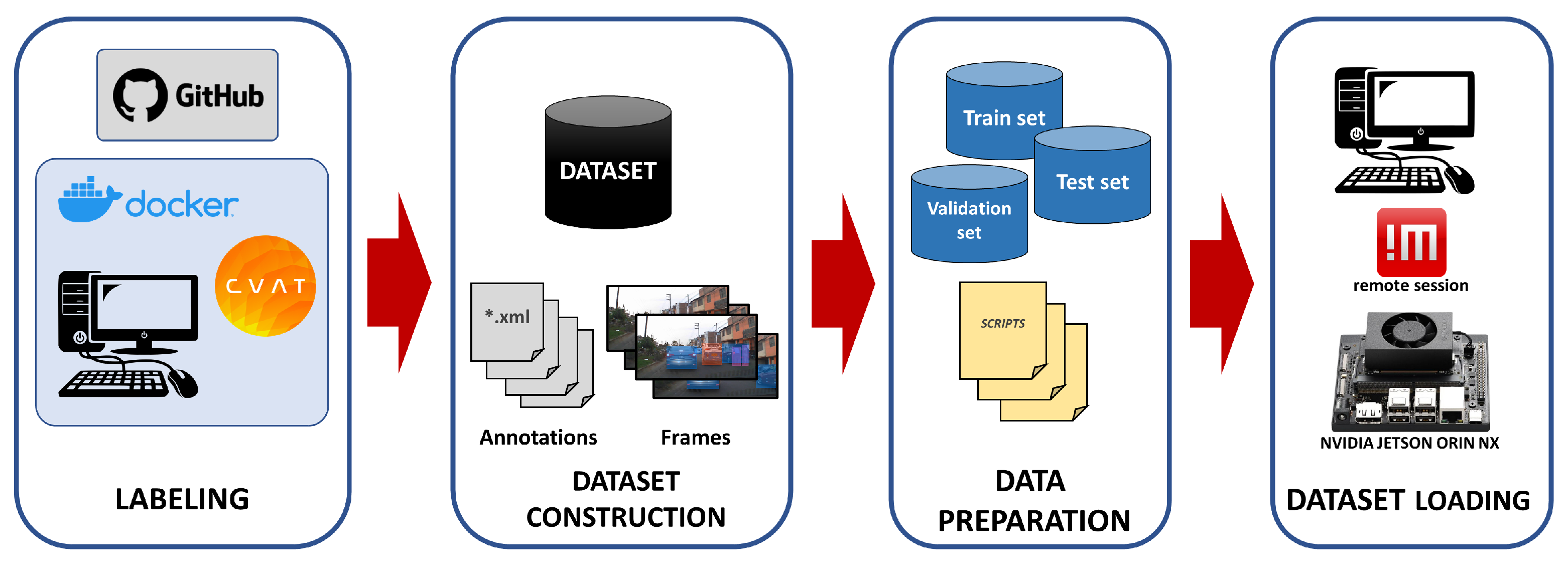

Figure 4.

Construction of video data into small segments.

Figure 4.

Construction of video data into small segments.

Figure 5.

Diagram for loading dataset on the Jetson platform.

Figure 5.

Diagram for loading dataset on the Jetson platform.

Figure 6.

Data augmentation by adjusting the dataset’s contrast.

Figure 6.

Data augmentation by adjusting the dataset’s contrast.

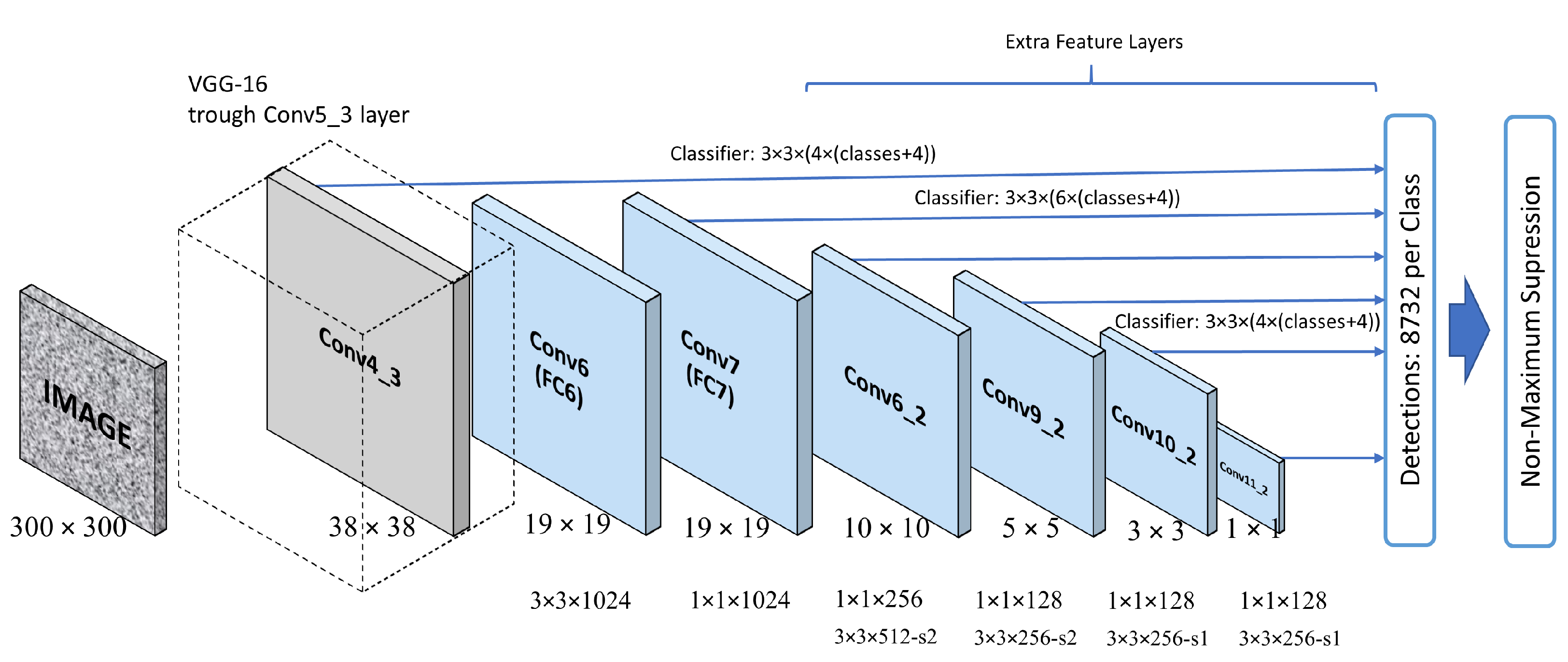

Figure 7.

Architecture of the Single-Shot-Detector model [

38].

Figure 7.

Architecture of the Single-Shot-Detector model [

38].

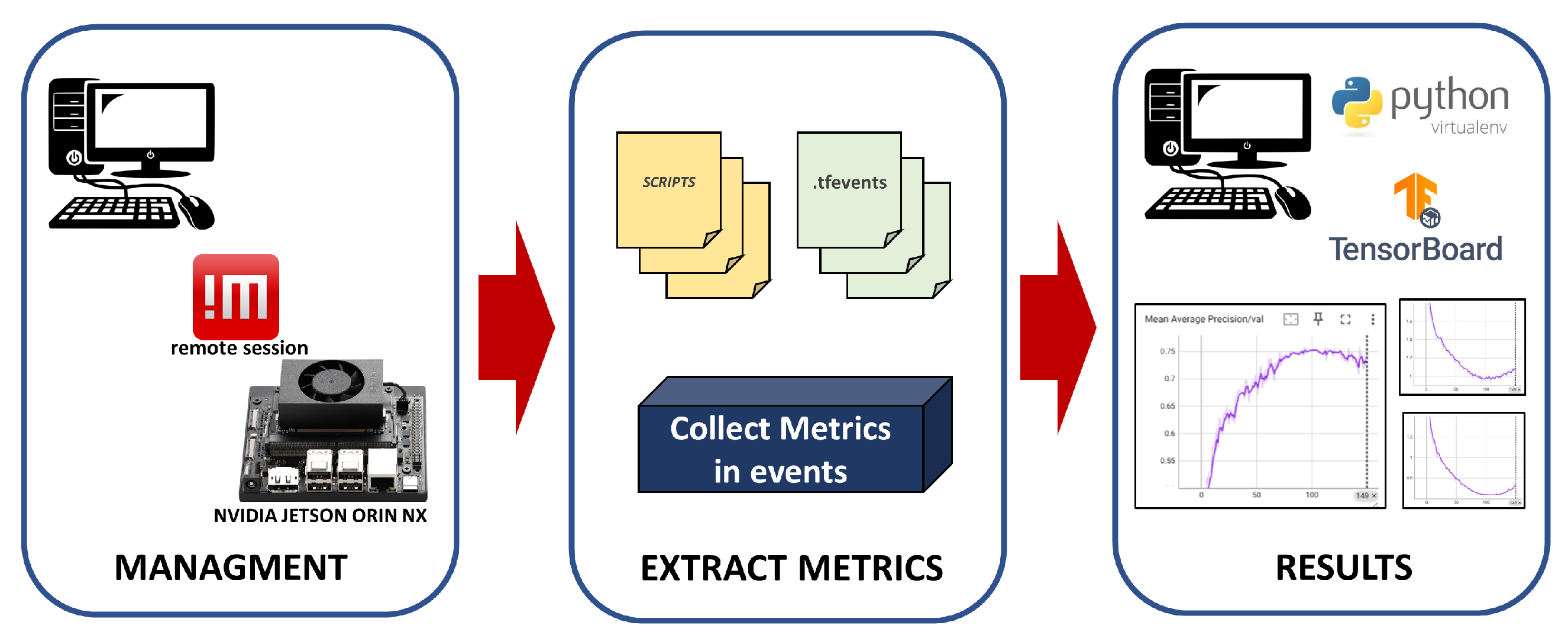

Figure 8.

Extract metrics from Jetson platform.

Figure 8.

Extract metrics from Jetson platform.

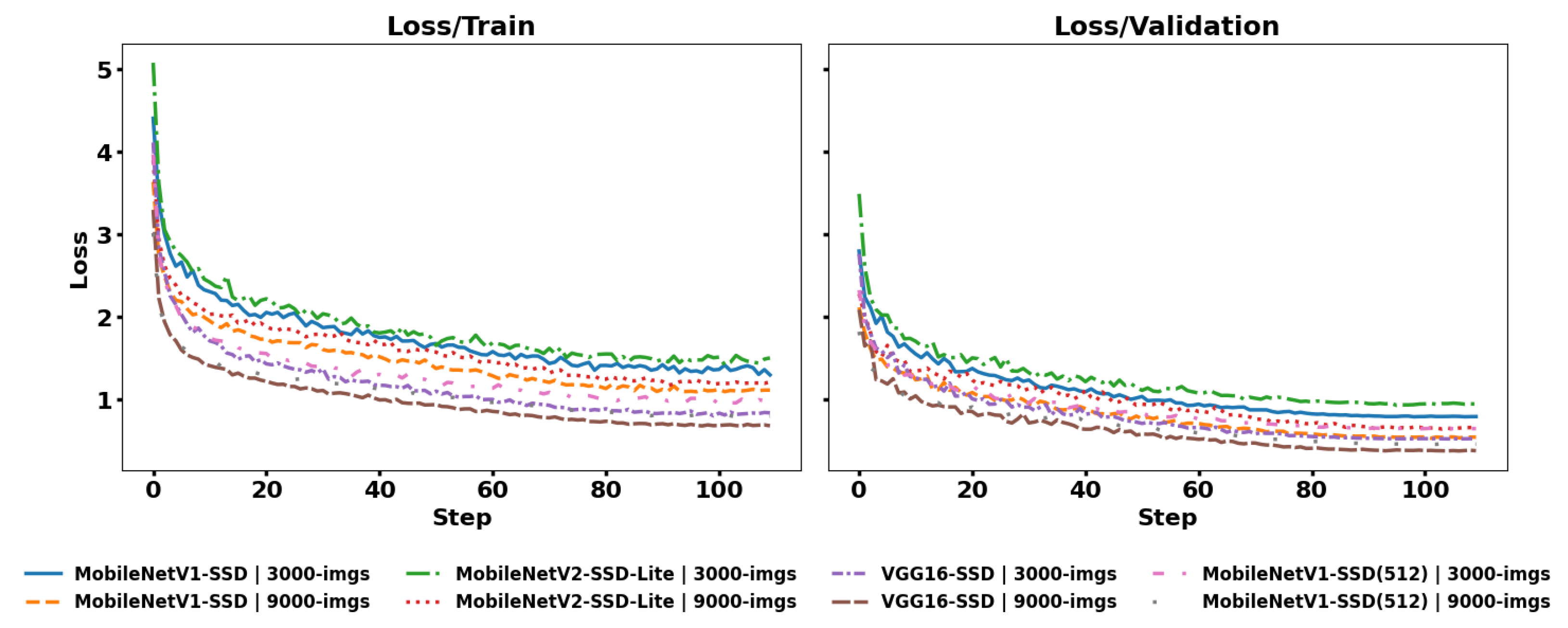

Figure 9.

Loss/train and loss/validation.

Figure 9.

Loss/train and loss/validation.

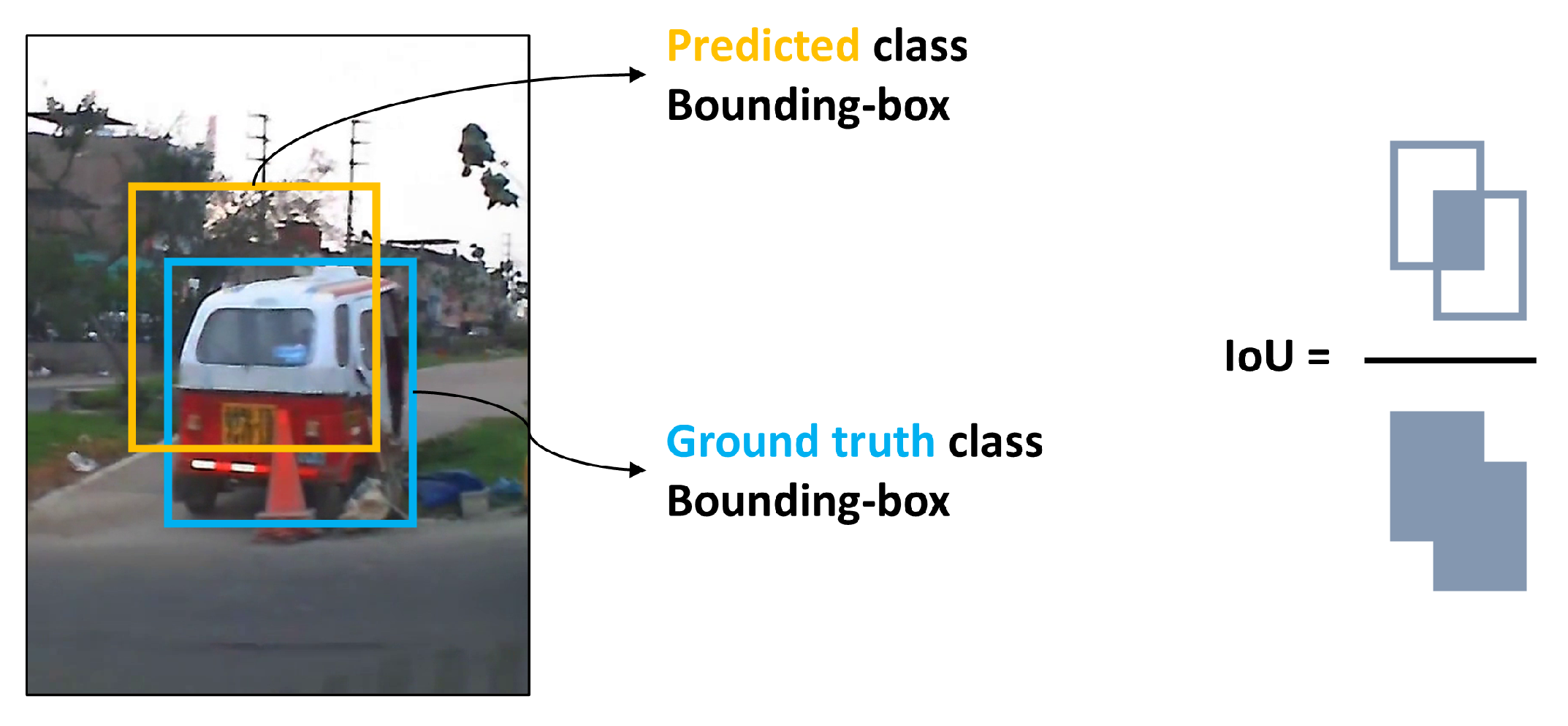

Figure 10.

Intersection over Union (IoU) score.

Figure 10.

Intersection over Union (IoU) score.

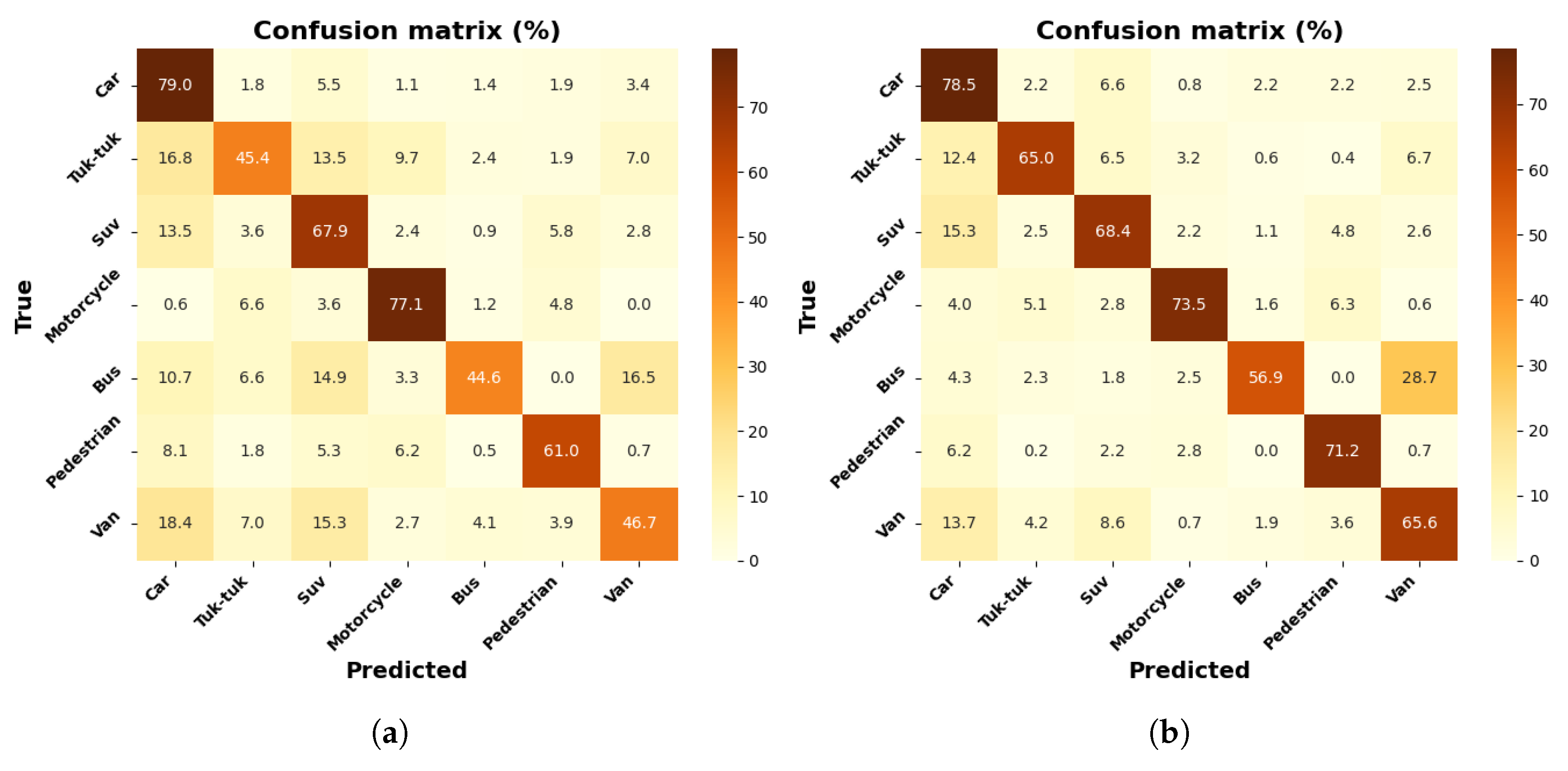

Figure 11.

Results with MobileNetV1-SSD model: (a) confusion matrix with a 3000 frame dataset; (b) confusion matrix with a 9000 frame dataset.

Figure 11.

Results with MobileNetV1-SSD model: (a) confusion matrix with a 3000 frame dataset; (b) confusion matrix with a 9000 frame dataset.

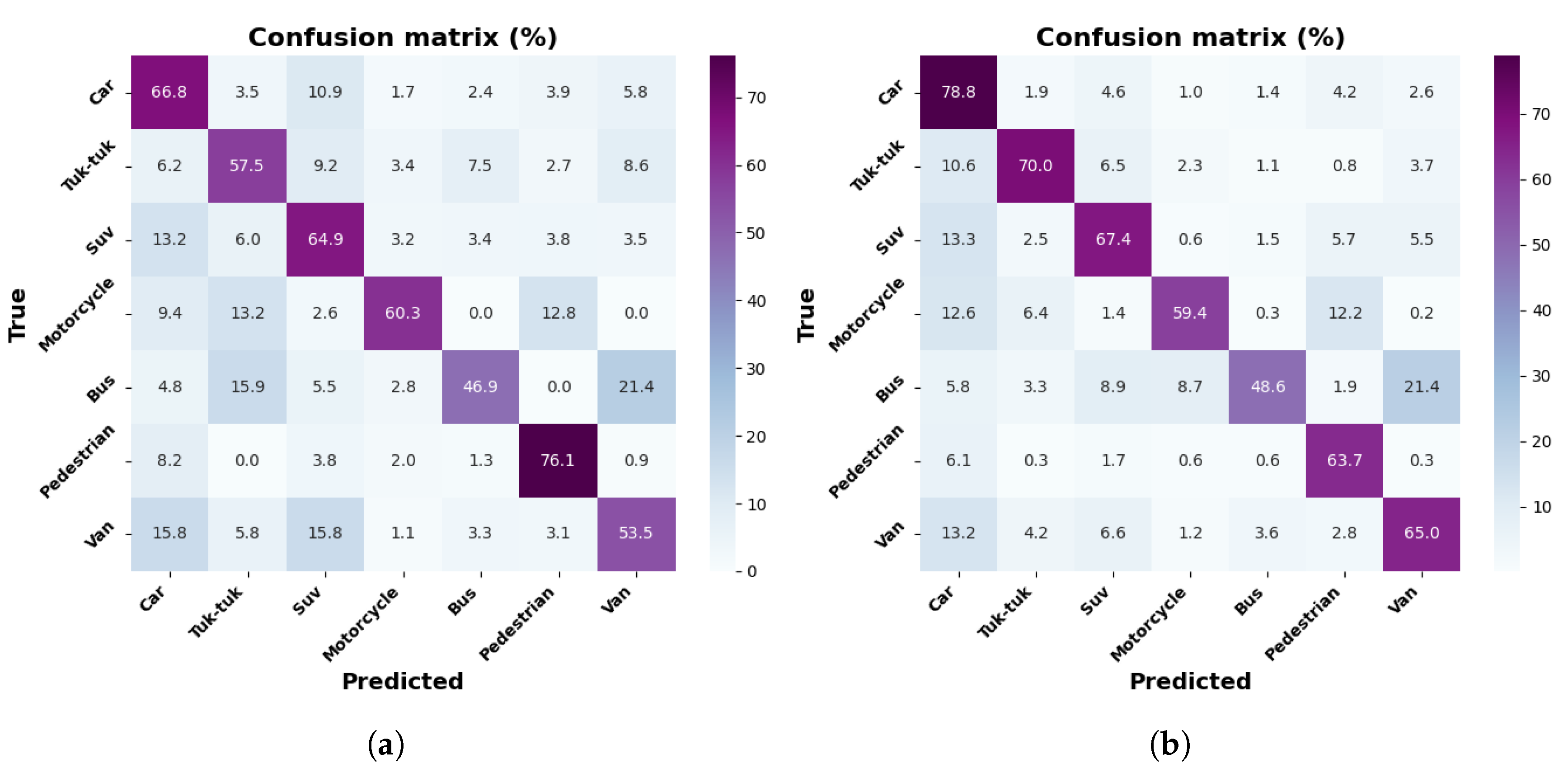

Figure 12.

Results with MobileNetV2-SSD-Lite model: (a) confusion matrix with 3000 frames dataset; (b) confusion matrix with 9000 frames dataset.

Figure 12.

Results with MobileNetV2-SSD-Lite model: (a) confusion matrix with 3000 frames dataset; (b) confusion matrix with 9000 frames dataset.

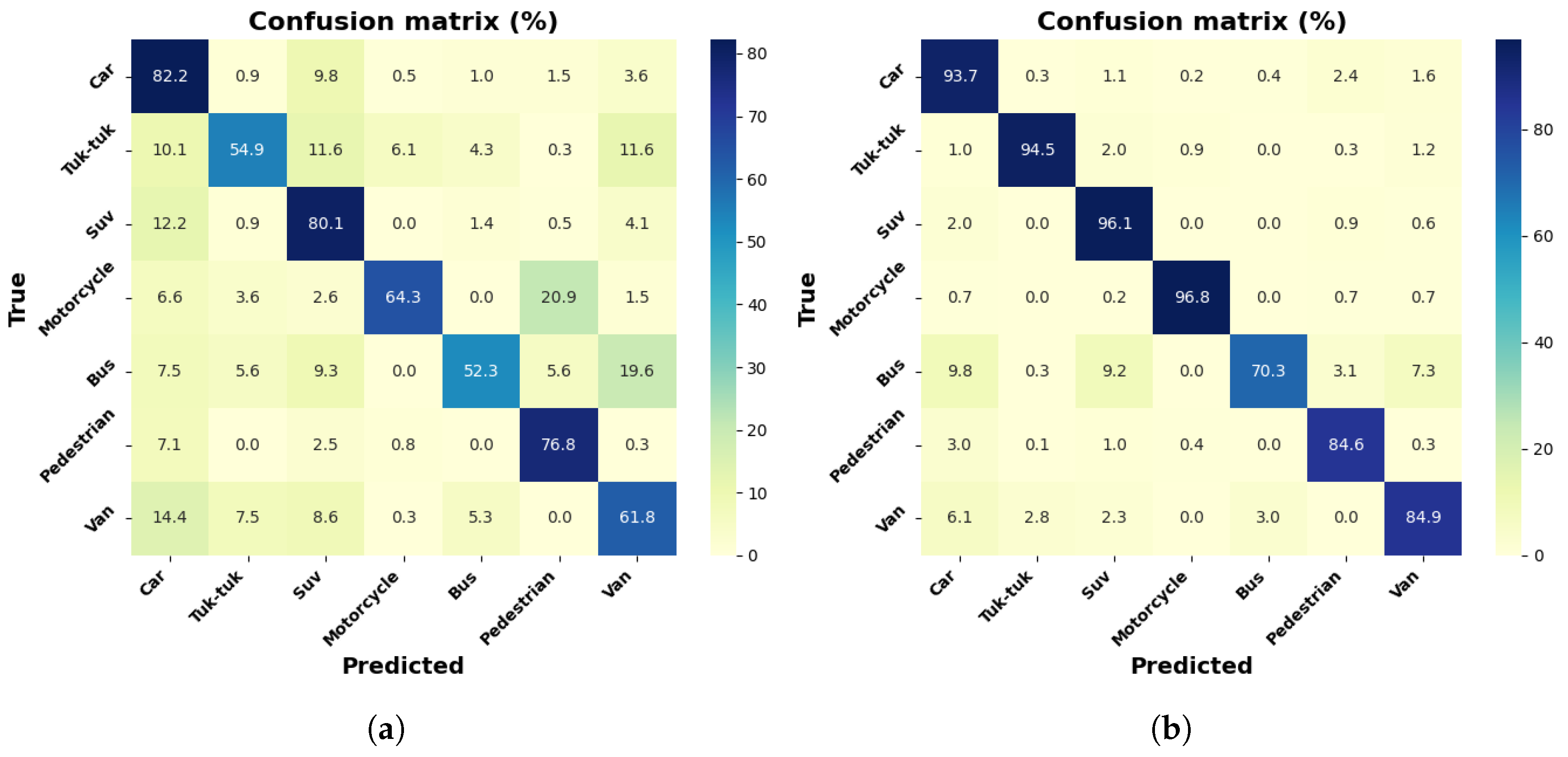

Figure 13.

Results with VGG16-SSD model: (a) confusion matrix with 3000 frames dataset; (b) confusion matrix with 9000 frames dataset.

Figure 13.

Results with VGG16-SSD model: (a) confusion matrix with 3000 frames dataset; (b) confusion matrix with 9000 frames dataset.

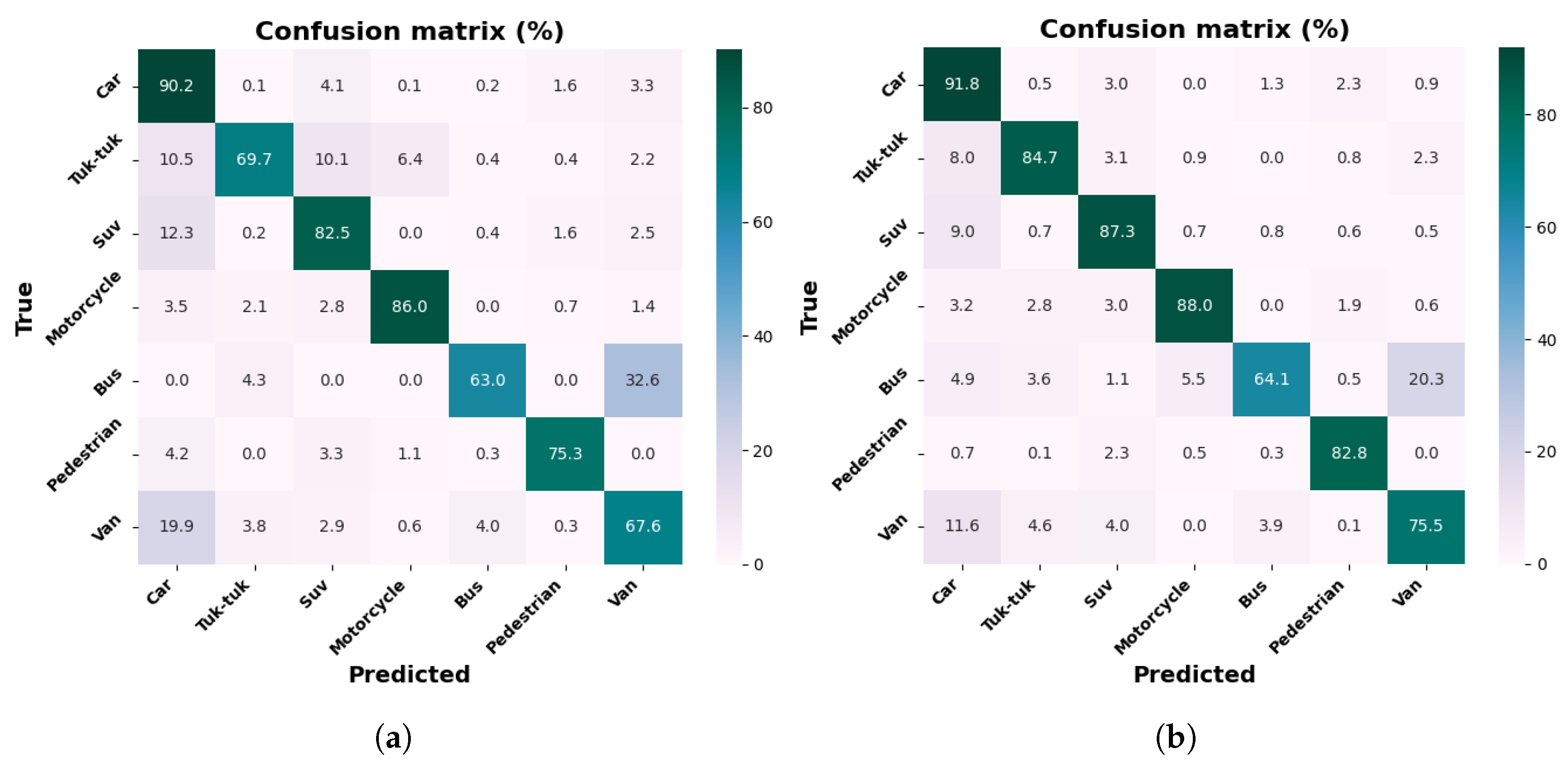

Figure 14.

Results with MobileNetV1-SSD model (512 × 512): (a) confusion matrix with 3000 frames dataset; (b) confusion matrix with 9000 frames dataset.

Figure 14.

Results with MobileNetV1-SSD model (512 × 512): (a) confusion matrix with 3000 frames dataset; (b) confusion matrix with 9000 frames dataset.

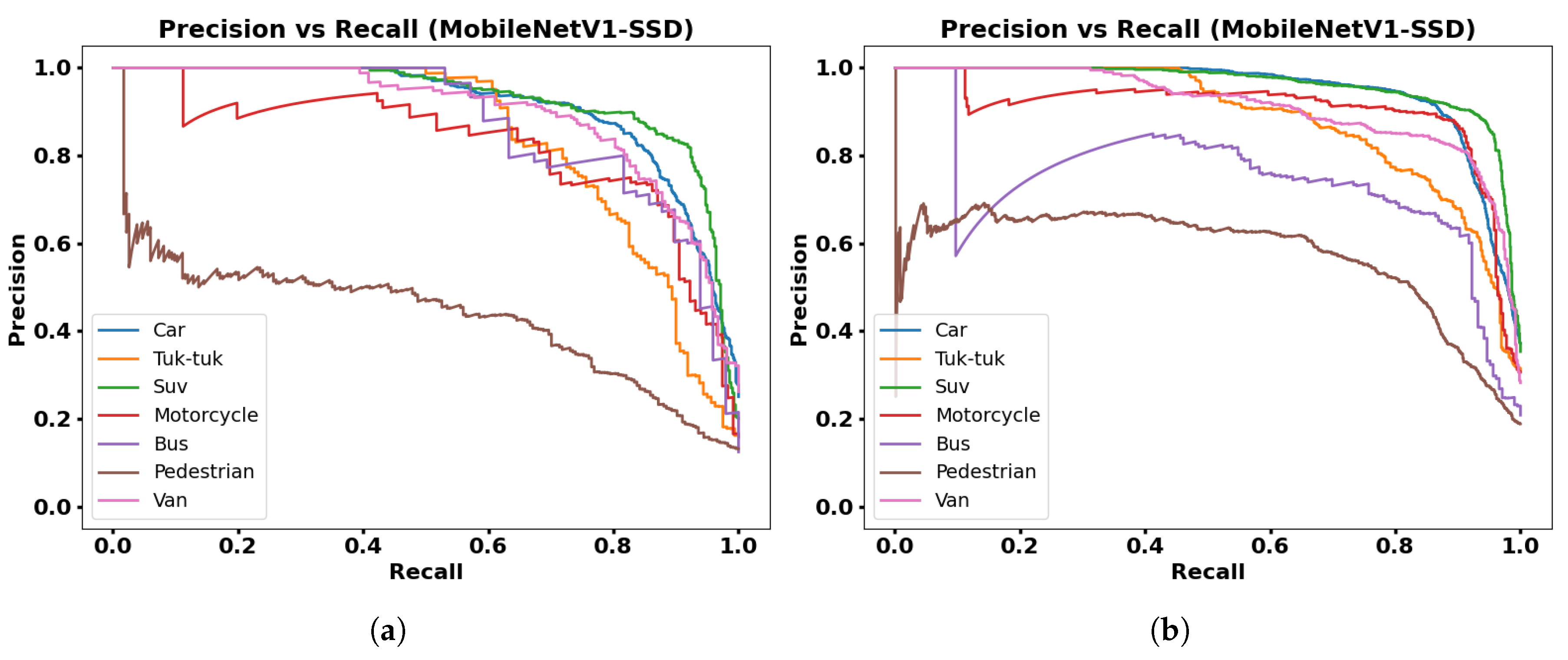

Figure 15.

Resultswith MobileNetV1-SSD model: (a) Precision vs. Recall with 3000 frames dataset; (b) Precision vs. Recall with 9000 frames dataset.

Figure 15.

Resultswith MobileNetV1-SSD model: (a) Precision vs. Recall with 3000 frames dataset; (b) Precision vs. Recall with 9000 frames dataset.

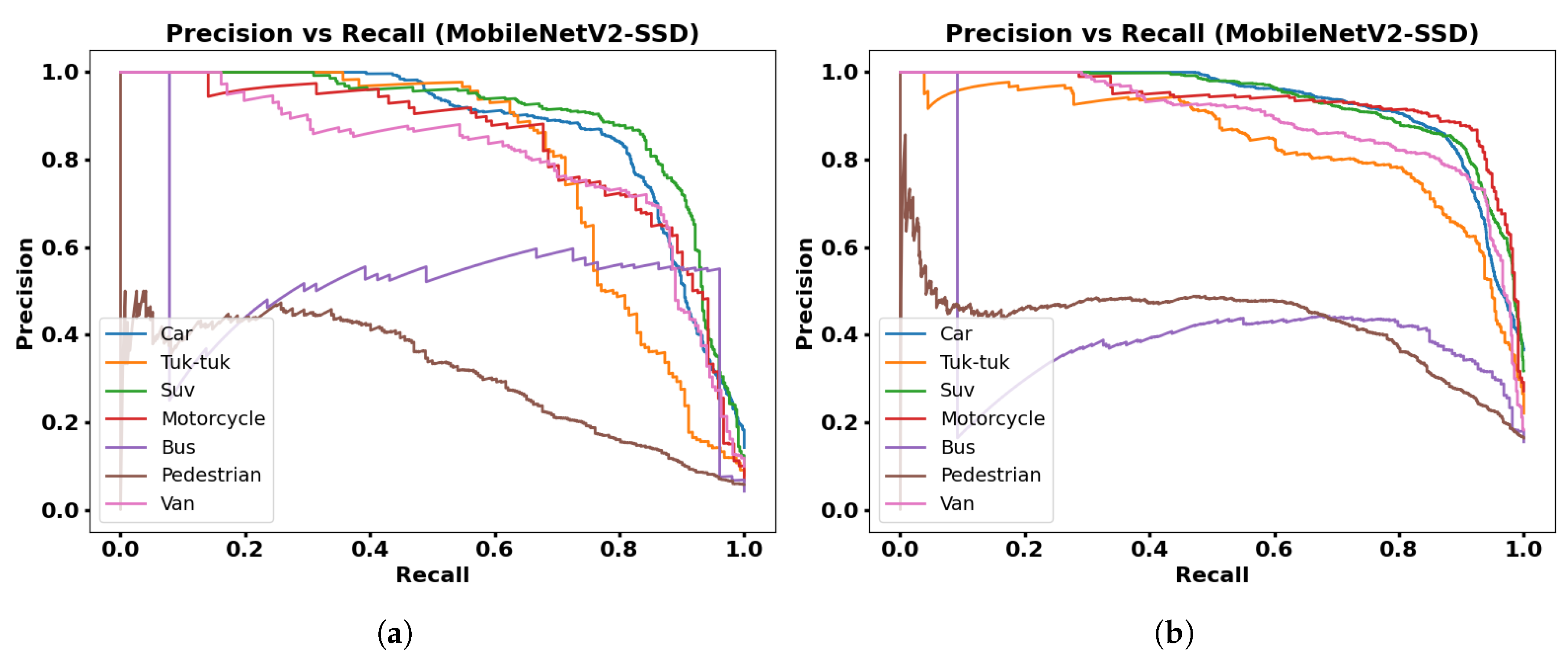

Figure 16.

Results with MobileNetV2-SSD-Lite model: (a) Precision vs. Recall with 3000 frames dataset; (b) Precision vs. Recall with 9000 frames dataset.

Figure 16.

Results with MobileNetV2-SSD-Lite model: (a) Precision vs. Recall with 3000 frames dataset; (b) Precision vs. Recall with 9000 frames dataset.

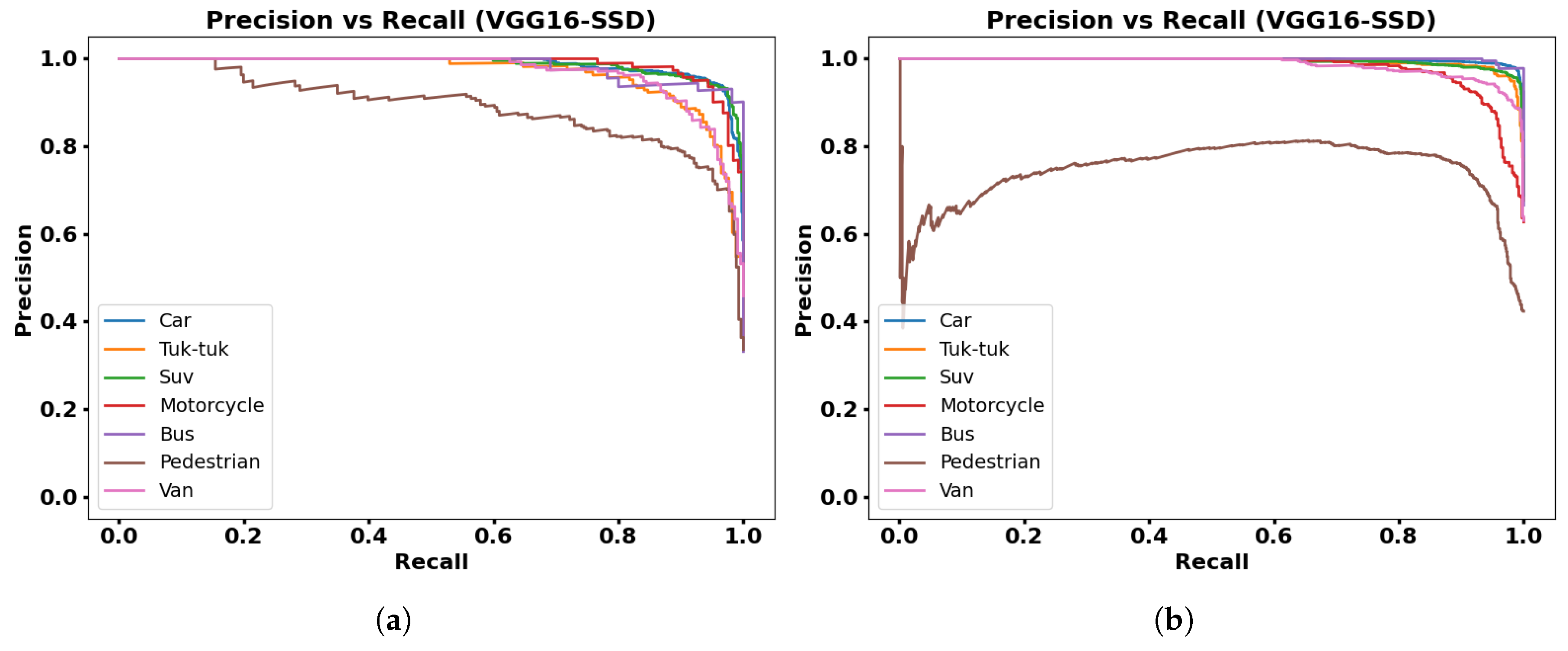

Figure 17.

Results with VGG16-SSD model: (a) Precision vs. Recall with 3000 frames dataset; (b) Precision vs. Recall with 9000 frames dataset.

Figure 17.

Results with VGG16-SSD model: (a) Precision vs. Recall with 3000 frames dataset; (b) Precision vs. Recall with 9000 frames dataset.

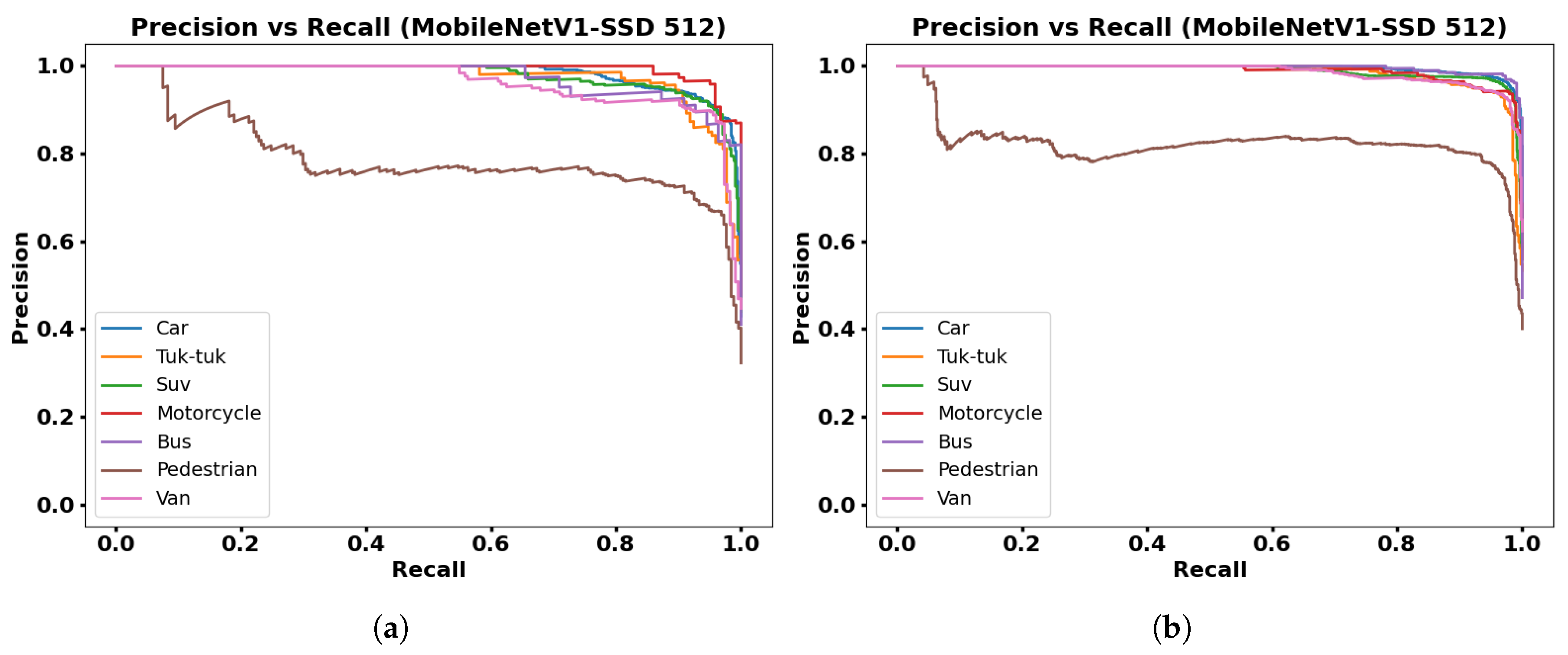

Figure 18.

Results with MobileNetV1-SSD model (512 × 512): (a) Precision vs. Recall with 3000 frames dataset; (b) Precision vs. Recall with 9000 frames dataset.

Figure 18.

Results with MobileNetV1-SSD model (512 × 512): (a) Precision vs. Recall with 3000 frames dataset; (b) Precision vs. Recall with 9000 frames dataset.

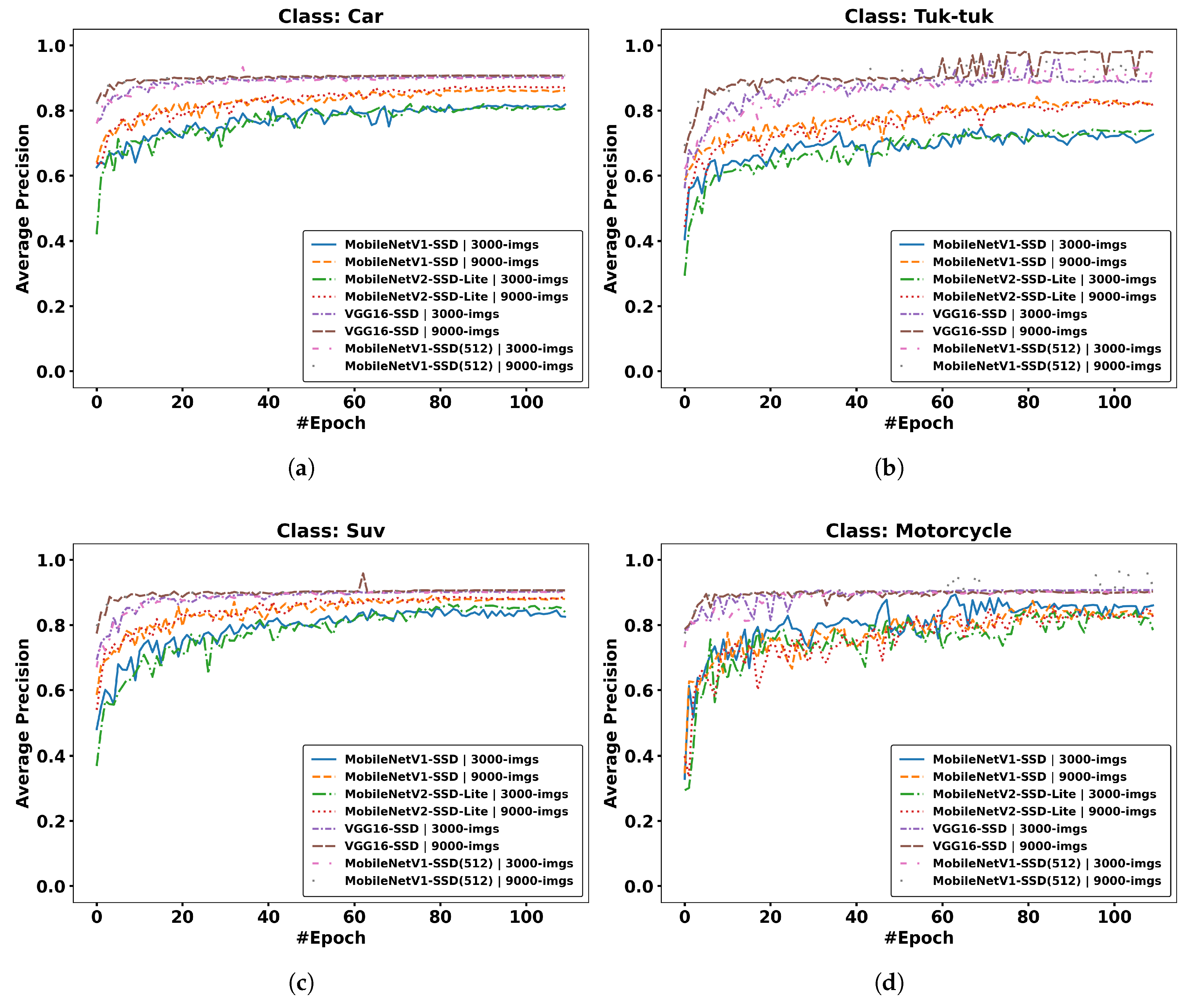

Figure 19.

Results per class, Average Precision vs. epoch: (a) Car; (b) Tuk-tuk; (c) Suv; (d) Motorcycle; (e) Bus; (f) Pedestrian; (g) Van.

Figure 19.

Results per class, Average Precision vs. epoch: (a) Car; (b) Tuk-tuk; (c) Suv; (d) Motorcycle; (e) Bus; (f) Pedestrian; (g) Van.

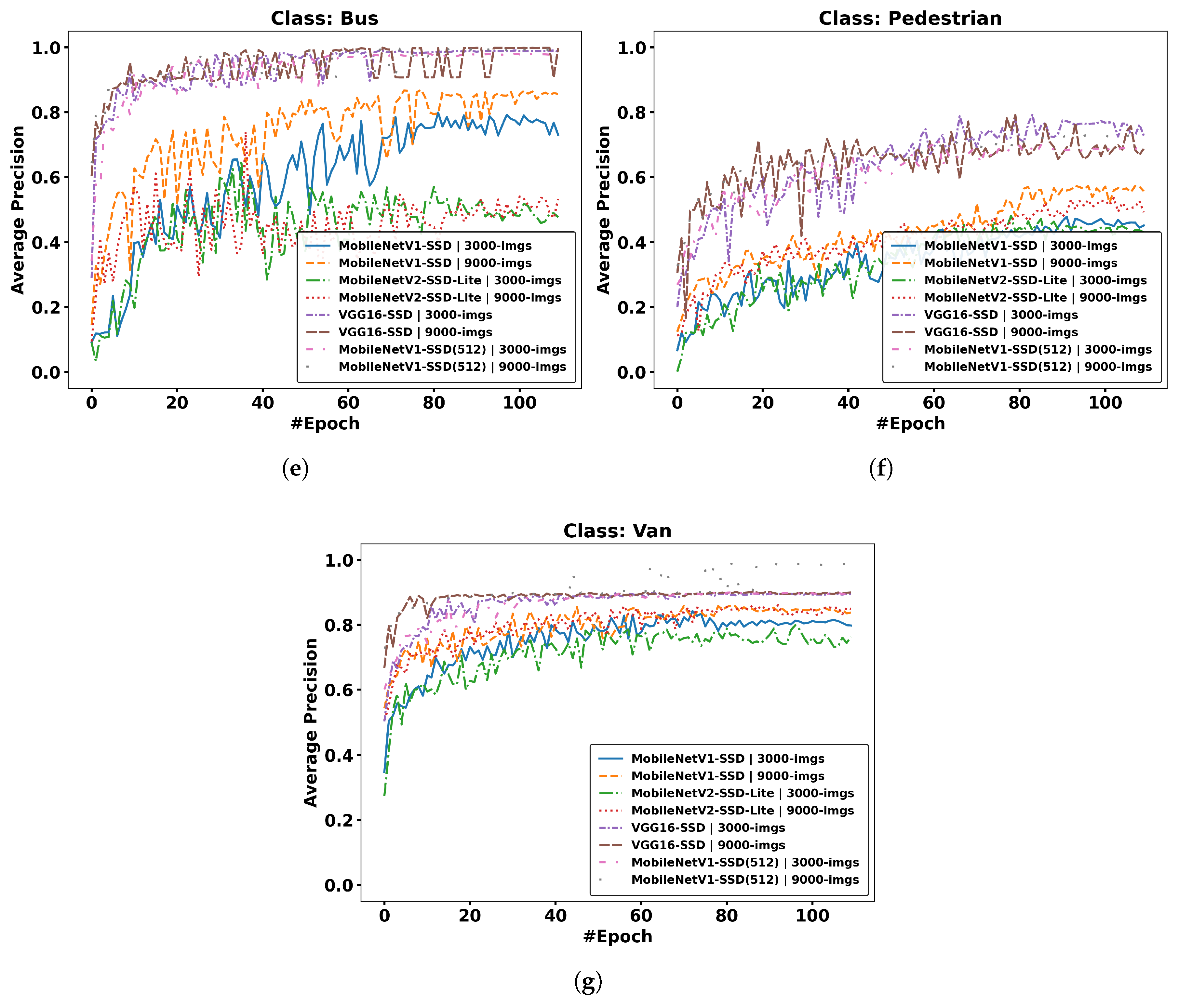

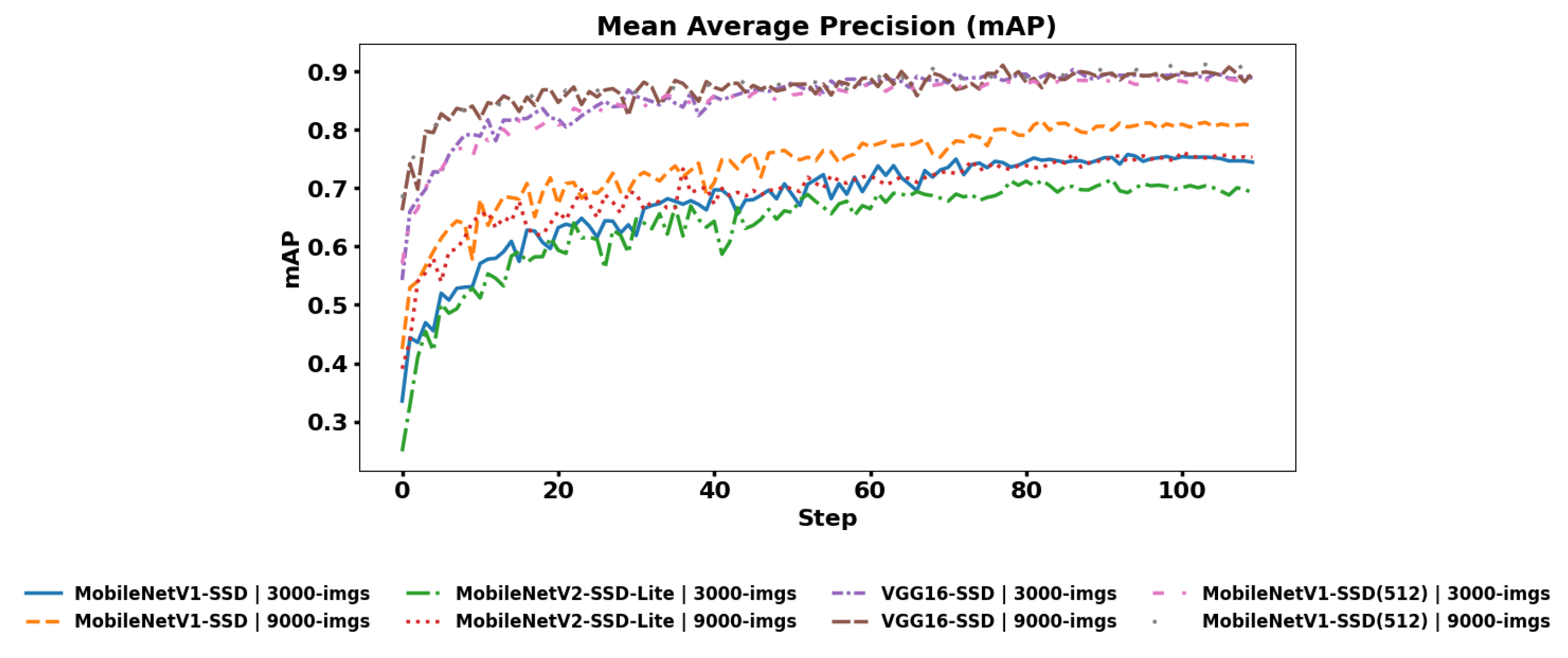

Figure 20.

Mean Average Precision for all classes for each model.

Figure 20.

Mean Average Precision for all classes for each model.

Figure 21.

Object detection using MobileNetV1-SSD (512 × 512) on an embedded platform.

Figure 21.

Object detection using MobileNetV1-SSD (512 × 512) on an embedded platform.

Table 1.

Distribution of classes in the dataset.

Table 1.

Distribution of classes in the dataset.

| # | Class | No. of Objects |

|---|

| 1 | Car | 4924 |

| 2 | Tuk-tuk | 1101 |

| 3 | SUV | 3082 |

| 4 | Motorcycle | 822 |

| 5 | Bus | 430 |

| 6 | Pedestrian | 2201 |

| 7 | Van | 1452 |

| | Total | 14,012 |

Table 2.

Class distribution.

Table 2.

Class distribution.

| # | Class | | Dataset (3000) | | | Dataset (9000) | |

|---|

| Train | Test | Val. | Train | Test | Val. |

|---|

| 1 | Car | 3297 | 772 | 855 | 10,064 | 2268 | 2440 |

| 2 | Tuk-tuk | 745 | 174 | 182 | 2188 | 531 | 584 |

| 3 | SUV | 2072 | 443 | 573 | 6165 | 1449 | 1650 |

| 4 | Motorcycle | 555 | 126 | 141 | 1679 | 390 | 397 |

| 5 | Bus | 272 | 55 | 103 | 857 | 225 | 208 |

| 6 | Pedestrian | 1500 | 312 | 389 | 4498 | 1057 | 1048 |

| 7 | Van | 966 | 226 | 260 | 2988 | 629 | 739 |

Table 3.

Arguments to train models.

Table 3.

Arguments to train models.

| # | Argument | Value(s) |

|---|

| 1 | –dataset-type | voc |

| 2 | –net | mb1-ssd; mb2-ssd-lite; vgg16-ssd |

| 3 | –resolution | 300; 512 |

| 4 | –pretrained-ssd | mobilenet-v1-ssd-mp-0_675.pth; mb2-ssd-lite-mp-0_686.pth; vgg16-ssd-mp-0_7726.pth |

| 5 | –batch-size | 4 |

| 6 | –epochs | 110 |

| 7 | –validation-epochs | 1 |

| 8 | –debug-steps | 10 |

| 9 | –use-cuda | True |

Table 4.

Report on the NVIDIA Jetson platform.

Table 4.

Report on the NVIDIA Jetson platform.

| Dataset | Model | # Step (Epoch) | Time | Loss/Val | mAP |

|---|

| | MobileNetV1-SSD (300 × 300) | 98 | 7.212 h | 0.7871 | 75.43 |

| 3000 frames | MobileNetV1-SSD (512 × 512) | 99 | 8.019 h | 0.6413 | 88.47 |

| | MobileNetV2-SSD-Lite | 95 | 7.966 h | 0.9252 | 70.71 |

| | VGG16-SSD | 106 | 13.19 h | 0.5194 | 88.79 |

| | MobileNetV1-SSD (300 × 300) | 101 | 1.105 days | 0.5272 | 80.44 |

| 9000 frames | MobileNetV1-SSD (512 × 512) | 106 | 1.103 days | 0.4539 | 90.44 |

| | MobileNetV2-SSD-Lite | 103 | 1.029 days | 0.6388 | 75.17 |

| | VGG16-SSD | 106 | 1.644 days | 0.3734 | 90.74 |

Table 5.

Report of the energy consumption.

Table 5.

Report of the energy consumption.

| Model | VDD Type | Voltage | Current | Power |

|---|

MobileNetV1-SSD

(300 × 300) | IN | 5087.80 mV | 1449.86 mA | 7374.64 mW |

| CPU_GPU_CV | 5072.86 mV | 442.60 mA | 2244.70 mW |

| SOC | 5080.00 mV | 320.54 mA | 1627.79 mW |

MobileNetV1-SSD

(512 × 512) | IN | 5088.00 mV | 1481.60 mA | 7538.90 mW |

| CPU_GPU_CV | 5072.00 mV | 461.60 mA | 2340.68 mW |

| SOC | 5080.00 mV | 324.13 mA | 1646.11 mW |

| | IN | 5088.00 mV | 1428.31 mA | 7263.58 mW |

| MobileNetV2-SSD-Lite | CPU_GPU_CV | 5074.77 mV | 431.38 mA | 2190.00 mW |

| | SOC | 5080.92 mV | 318.15 mA | 1615.77 mW |

Table 6.

Performance of inference comparison: MobileNetV1-SSD vs. YOLO-v8-Nano.

Table 6.

Performance of inference comparison: MobileNetV1-SSD vs. YOLO-v8-Nano.

| Model | #Parameters | Size (Engine) | Latency (Mean) | Latency (Median) | Latency (P-99%) | FPS | Metric (Value) |

|---|

| MobileNetV1-SSD | 7.48 M | 30.6 MB | ≈12.446 ms | ≈12.380 ms | ≈13.987 ms | ≈81 | mAP = 90.4% |

| YOLO-v8n | 3.03 M | 13.3 MB | ≈11.134 ms | ≈10.927 ms | ≈15.740 ms | ≈92 | mAP = 91.7% |

Table 7.

Timing report comparison: MobileNetV1-SSD vs. YOLO-v8-Nano.

Table 7.

Timing report comparison: MobileNetV1-SSD vs. YOLO-v8-Nano.

| Stages | MobileNetV1-SSD | YOLO-v8-Nano |

|---|

| Pre-Process | ≈0.1 ms | ≈5.4 ms |

| Network | ≈9.0 ms | ≈7.8 ms |

| Post-Process | ≈0.2 ms | ≈14.9 ms |

| Total Time | ≈9.3 ms | ≈28.1 ms |

Table 8.

Report of the energy consumption: MobileNetV1-SSD vs. YOLO-v8-Nano.

Table 8.

Report of the energy consumption: MobileNetV1-SSD vs. YOLO-v8-Nano.

| | | MobileNetV1-SSD | | | YOLO-v8-Nano | |

|---|

| VDD Type | Voltage | Current | Power | Voltage | Current | Power |

|---|

| IN | 5088.00 mV | 1417.71 mA | 7212.86 mW | 5088.00 mV | 1468.00 mA | 7560.38 mW |

| CPU_GPU_CV | 5073.71 mV | 424.57 mA | 2153.71 mW | 5073.00 mV | 437.00 mA | 2221.50 mW |

| SOC | 5080.00 mV | 316.00 mA | 1607.43 mW | 5080.00 mV | 333.00 mA | 1691.13 mW |

Table 9.

Performance comparison with the literature.

Table 9.

Performance comparison with the literature.

| Reference | Model | Embedded-Plataform | Classes | Metric (Value) |

|---|

| Barba-Guaman et al., 2020 [43] | PedNet | Jetson Nano | car, pedestrian | Acc. = 78.71% |

| Farooq et al., 2021 [44] | YOLO-v5 | Jetson Nano | bike, bus, bycicle, car, dog, person, pole | mAP = 85.5% |

| Elmanaa et al., 2023 [45] | YOLO-v7-tiny | Jetson Nano | car, bus, motorcycle, truck | mAP = 80.1% |

| Liang et al., 2024 [46] | YOLO-v7-tiny (prune) | Jetson Xavier AGX | car, cyclist, pedestrian, tram, tricycle, truck | mAP = 72.5% |

| This work | MobileNetV1-SSD (512 × 512) | Jetson Orin NX | bus, car, motorcycle, pedestrian, suv, tuk-tuk, van | mAP = 90.44% |