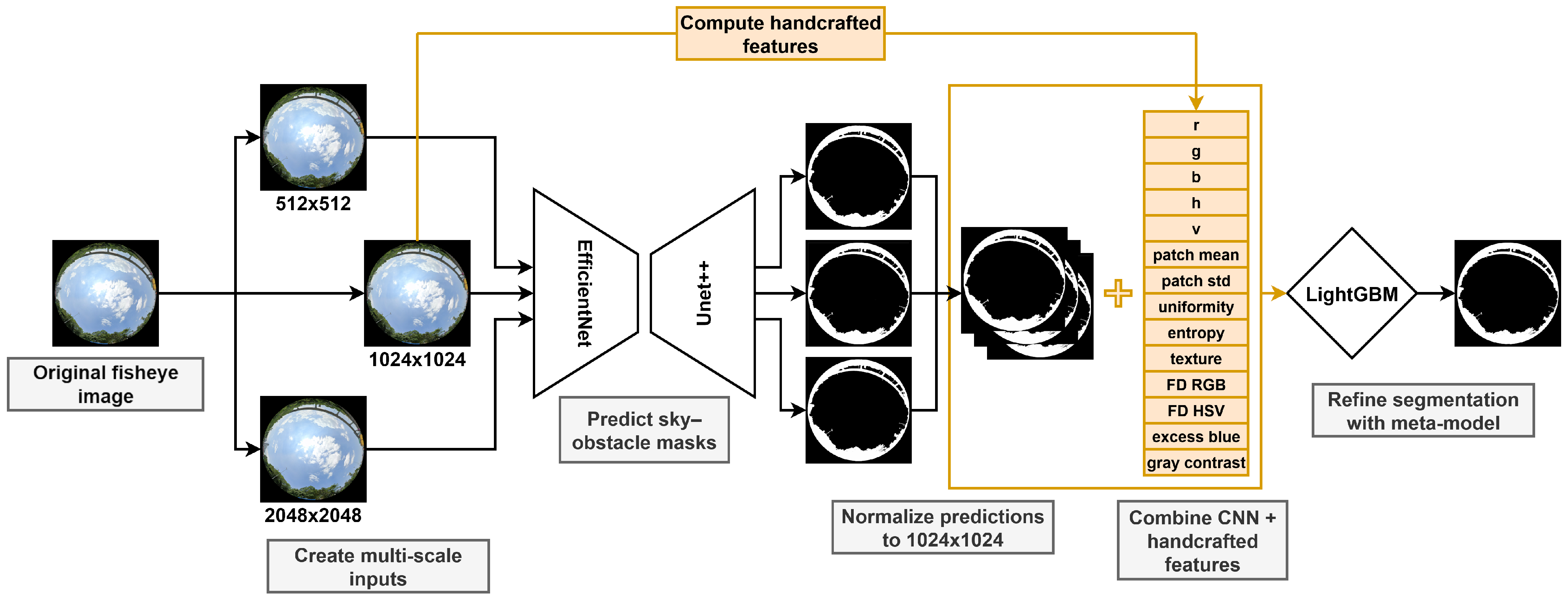

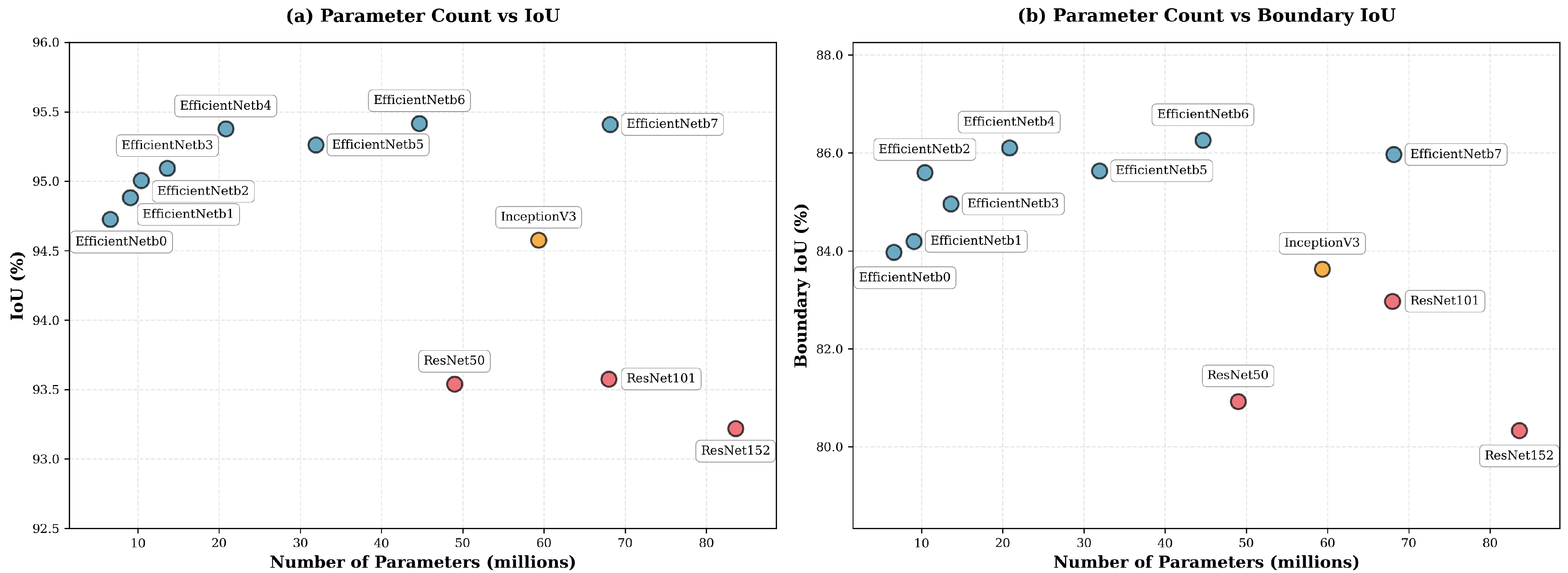

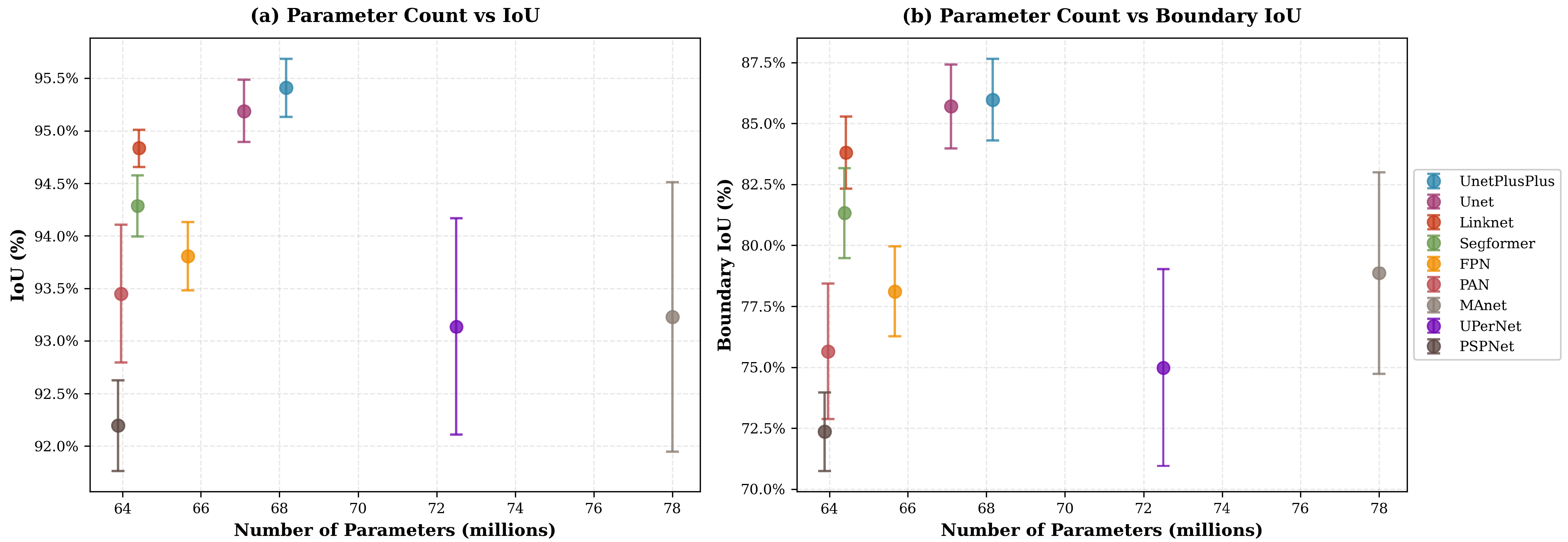

4.1. Model Evaluation

To evaluate the final segmentation performance, we trained U-Net++ models with EfficientNet-b4, b5, b6, and b7 encoders, corresponding to the top-performing backbones identified in the architecture benchmark. Model performance was assessed using the F1 score and IoU, computed as weighted averages by class support. In addition, we report two boundary-focused metrics: Boundary IoU [

58] and Boundary F1 [

59]. Boundary IoU evaluates overlap only within narrow bands around the predicted and ground-truth contours, yielding a boundary-sensitive analogue of IoU that is symmetric and less biased by region interiors; we follow the reference implementation and use a dilation ratio of

. Boundary F1 (also called the boundary F-measure) is the harmonic mean of boundary precision and recall under a small localization tolerance; throughout this work we use a tolerance of

pixels. These complementary measures directly target skyline fidelity and contour alignment. Baseline CNN-only results are summarized in

Table 5.

For each encoder, we further trained a dedicated post-processing meta-model based on LightGBM, as described in

Section 3.2.5. Hyperparameter tuning was conducted using Optuna [

60]. During training, we employed early stopping on the validation metric to automatically select the effective number of boosting iterations (trees). In practice, early stopping consistently halted training after fewer than 100 trees across all configurations, resulting in compact boosted tree models and keeping the post-processing stage lightweight. To convert the probabilistic output of the LGBM model into a binary mask, we evaluated several thresholding strategies: simple fixed thresholding, Otsu’s method [

61], and Conditional Random Fields (CRF) [

62]. Empirically, a single fixed decision threshold tuned on the validation set yielded the best overall results for all encoders. The results obtained with LGBM post-processing are summarized in

Table 6.

The LGBM post-processing module yields consistent improvements over the CNN-only baselines for all EfficientNet variants, enhancing both region-level and boundary-focused metrics. Across encoders, IoU increases by roughly –, while Boundary IoU and Boundary F1 improve by up to about and , respectively. Although these absolute gains may appear modest, on 1024 × 1024 images they correspond to correcting misclassified labels over thousands of pixels per frame, predominantly along object boundaries, which is perceptually significant for skyline delineation. Among the refined models, EfficientNet-b7 attains the highest region-level F1, IoU, and Boundary F1, whereas EfficientNet-b6 slightly outperforms it on Boundary IoU. EfficientNet-b4 closely matches b5 in region metrics but remains noticeably weaker on boundary scores, reinforcing the importance of explicitly evaluating boundary-sensitive criteria. In practice, this results in a clear accuracy–efficiency trade-off: EfficientNet-b7 maximizes segmentation quality, while smaller variants (b4–b6) sacrifice only a small amount of performance in exchange for substantially fewer parameters and more lightweight inference. Overall, combining a deep segmentation backbone with a supervised refinement layer yields precise sky–obstacle delineation with improved region overlap and markedly enhanced skyline fidelity across a range of model capacities.

In addition to the region-level and boundary-focused metrics, we also examine confusion matrices for the LGBM-refined models, shown in

Figure 8. These matrices provide a class-wise view of prediction behaviour by separating errors into false-sky (obstacle pixels predicted as sky) and false-obstacle (sky pixels predicted as obstacles). For solar irradiance forecasting, a pessimistic model is preferable: it should be more inclined to label ambiguous pixels as obstacles rather than sky, so that irradiance is slightly underestimated rather than overestimated. Among the tested variants, the LGBM + EfficientNet-b7 model best matches this behaviour, achieving the lowest false-sky rate while accepting a slightly higher false-obstacle rate compared to the other architectures.

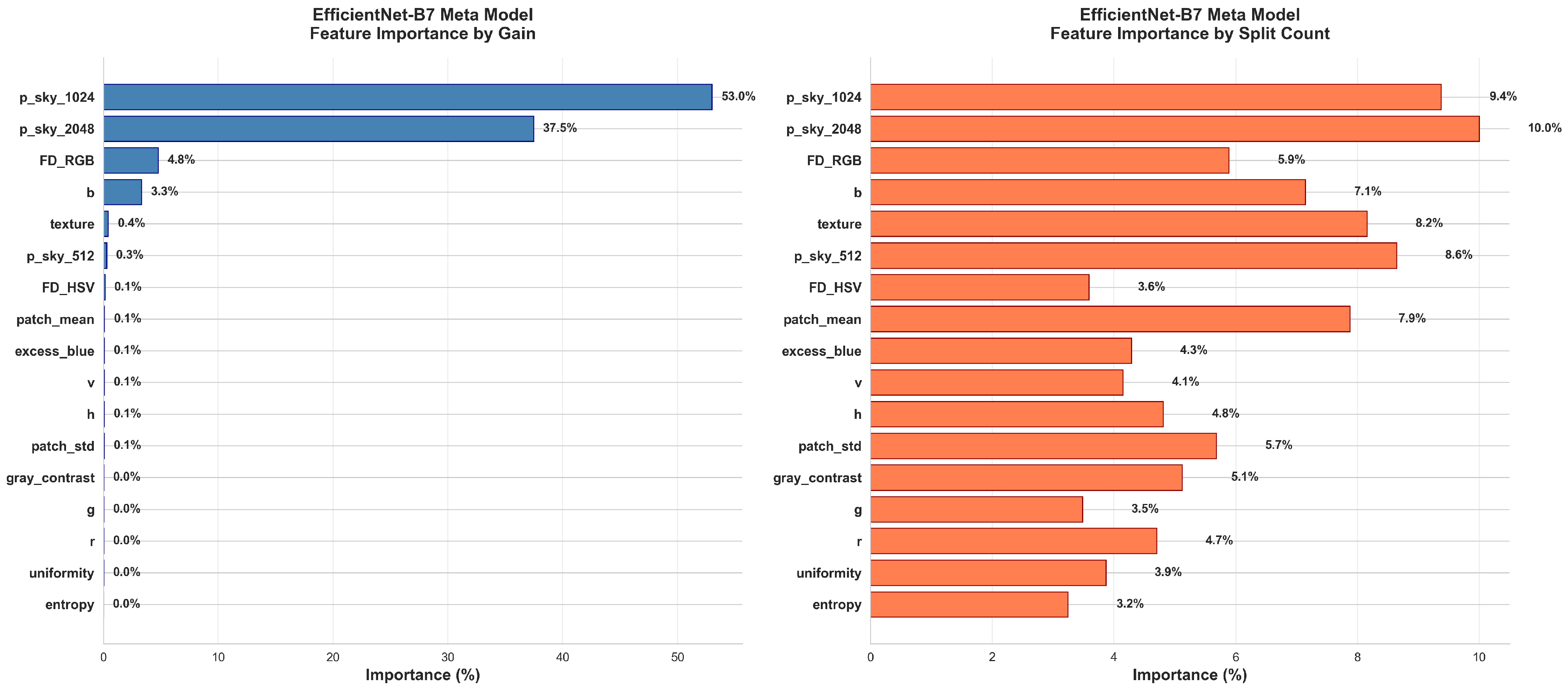

To better understand which features drive the improved segmentation accuracy, we analyzed representative LightGBM meta-models using SHAP [

63]. We focus here on the EfficientNet-b5 and EfficientNet-b7 backbones, which span mid to high-capacity encoders.

Figure 9 shows that the most impactful features across both configurations include multi-scale CNN predictions (p_sky_2048, p_sky_1024, p_sky_512), along with handcrafted descriptors such as Fisher Discriminant in RGB space, blue channel intensity, and texture. This highlights the value of combining deep and handcrafted features for reliable sky–obstacle boundary refinement, especially across varying spatial resolutions.

To complement the SHAP-based interpretation, the built-in LightGBM feature importances were also examined using the gain and split count criteria (

Figure 10) for the same two representative configurations. The gain metric measures how much each feature contributes to the reduction of the loss function, whereas the split count reflects how frequently a feature is selected across all decision trees.

In both EfficientNet-b5 and b7 meta-models, the multi-scale CNN predictions dominate the gain ranking, confirming that the base segmentation probabilities are the most informative predictors for sky–obstacle discrimination. However, the split count analysis reveals a broader distribution, with local statistical, textural, and color-based features appearing more frequently in splits. These features provide complementary thresholds that support fine-grained boundary refinement, even if their overall contribution remains smaller.

Minor differences between gain and split rankings mainly arise from correlations among color and luminance-related descriptors, reflecting mild multicollinearity effects also observed in the SHAP analysis. Overall, both analyses confirm that the LightGBM meta-model primarily relies on multi-scale CNN-derived probabilities while leveraging handcrafted features to adjust decision boundaries in visually complex regions.

4.2. Impact of the New Augmentations on Model Performance

To evaluate the contribution of chromatic aberration and fisheye lens distortion augmentations, we conducted an ablation study where both were omitted. EfficientNet-b5 and EfficientNet-b7 encoders with a U-Net++ decoder were trained following the same protocol described in

Section 3.2.4, and each configuration was repeated across 10 independent runs. We report the mean IoU and standard deviation to account for variability.

When trained without the augmentations, EfficientNet-b5 achieved a mean IoU of , compared to with augmentations. For EfficientNet-b7, the mean IoU dropped from (with augmentations) to (without augmentations).

Although the numerical differences are modest, these results indicate that the proposed augmentations provide measurable benefits. More importantly, they enhance robustness by exposing models to optical variability, thereby supporting improved generalization across diverse lenses and imaging conditions. This is particularly valuable for real-world deployment, where heterogeneous hardware and optical characteristics are common.

4.3. Qualitative Analysis of Model Predictions

Figure 11 illustrates the advantage of using a LightGBM meta-model to enhance segmentation predictions. At

resolution, a segmentation error is visible in the red-highlighted area, where a section of the sky is occluded by an overhead obstacle. Interestingly, this error is absent in the

prediction, which better captures large structural context but suffers from coarser boundary precision, as seen in the blue-highlighted region. In contrast, the

prediction preserves fine details but can be less stable in large homogeneous regions. The LightGBM model effectively fuses the strengths of predictions at different resolutions, producing a refined output that minimizes both types of error.

To better understand how the meta-model exploits these complementary behaviours,

Figure 12 reports local SHAP waterfall plots for two representative sky pixels taken from the red and blue areas in

Figure 11. In both cases, the desired output is a probability close to zero, corresponding to the sky class. For the pixel located in a homogeneous sky region (red area, left panel), the prediction values at

and

strongly push the model towards the obstacle class, but this tendency is counteracted by the prediction at

together with several handcrafted descriptors (blue-channel intensity, Fisher Discriminant, texture, Excess Blue, and local statistics), which contribute in the opposite direction and keep the final probability close to zero. For the pixel on a heterogeneous boundary (blue area, right panel), the situation is reversed: the coarse prediction at

and the local texture favour the obstacle class, while the finer-scale prediction at

and

, along with Fisher Discriminant and other colour features, pulls the score back towards the sky class.

Formally, the LightGBM model outputs a logit value

for each pixel, which is decomposed by SHAP as

where

is the global base value (the expected logit over the training data) and

is the contribution of feature

i for that pixel. The corresponding obstacle probability is obtained by applying the sigmoid function

For the homogeneous-sky pixel, the base value is

and the sum of all SHAP contributions is

. The raw logit is therefore

and the obstacle probability becomes

For the boundary sky pixel, the same base value combines with a SHAP sum of

, giving

and thus

These examples illustrate how the meta-model adaptively reweights the multi-scale prediction values and handcrafted features so that, even when one scale misclassifies a pixel, the final decision remains consistent with the sky label.

This multi-scale fusion strategy proves especially useful in heterogeneous environments: low-resolution predictions (e.g., 512 × 512) improve structural coherence in urban settings with frequent occlusions, while high-resolution predictions (e.g., 2048 × 2048) preserve fine details important in rural or vegetated landscapes.

Figure 13 presents additional qualitative results for the EfficientNet-b5 and EfficientNet-b7 models across a variety of urban and rural scenes. Both models demonstrate strong generalization across environments, with the LGBM post-processing consistently correcting local errors and improving edge coherence. These visualizations support the quantitative performance gains reported in

Section 4.3, highlighting the practical robustness of the combined segmentation pipeline in real-world scenarios.

4.4. Comparison with an External Baseline

As highlighted in

Section 1.3, direct comparison with existing segmentation benchmarks is hindered by the scarcity of high-quality fisheye datasets with accurate sky annotations. However, we identified a recent work [

64] that employs a similar methodology using equirectangular panoramas from Google Street View. This study introduces the CVRG-Pano dataset and proposes two U-Net-based architectures for semantic segmentation of panoramic imagery.

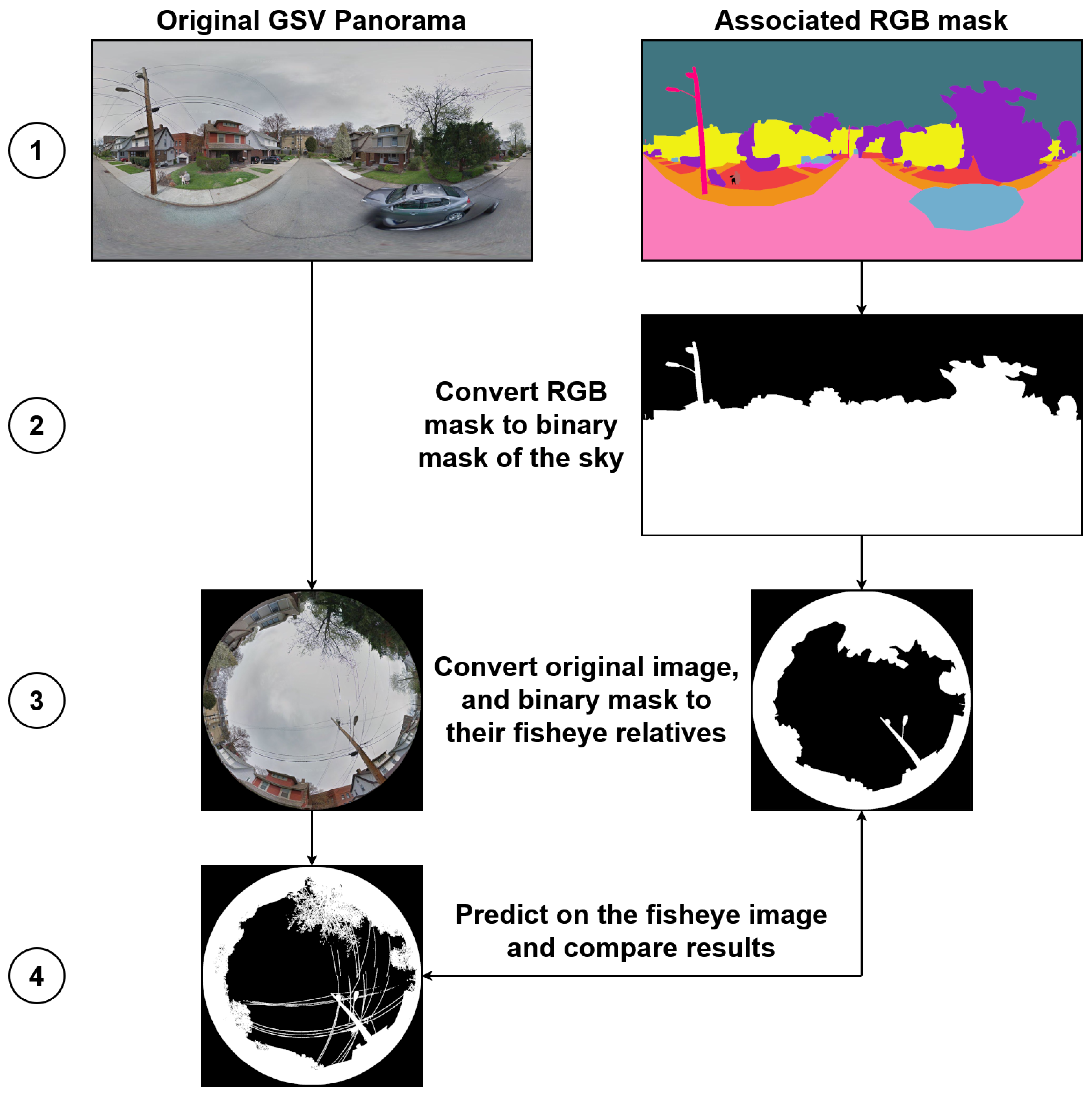

To enable a fair comparison, we employed our fisheye transformation pipeline to convert the CVRG-Pano test images and their associated multi-class masks into the fisheye domain. The evaluation procedure is summarized in

Figure 14. In step 1, each panoramic image is paired with its ground-truth semantic mask. In step 2, the RGB mask is converted to a binary sky mask. Step 3 involves projecting both the RGB image and the binary sky mask into the fisheye domain using the equidistant projection model, which is representative of low-cost commercial fisheye lenses. Finally, in step 4, we perform sky segmentation using our trained U-Net++ models with EfficientNet-b4, b5, b6, and b7 backbones, each evaluated with and without LightGBM-based post-processing refinement.

We report IoU scores in

Table 7. Despite annotation inconsistencies in CVRG-Pano, such as coarse boundaries and the omission of fine-grained obstacles like cables and thin branches, our models maintain strong generalization and achieve high performance, even on data not tailored for precise sky–obstacle segmentation.

The IoU values of the base models on CVRG-Pano closely match those obtained on our internal fisheye test set, indicating good cross-dataset generalization. In contrast to our own dataset, LightGBM post-processing does not systematically improve IoU here: three backbones (b4–b6) exhibit a slight decrease, while EfficientNet-b7 shows only a modest gain. This behaviour is consistent with the nature of the CVRG-Pano annotations, whose coarse boundaries and missing small obstacles penalize boundary-focused refinements that produce sharper, more detailed skylines than those represented in the ground truth. In other words, the meta-model tends to correct visually plausible fine structures (e.g., tree crowns, cables) that are not labeled, which can reduce IoU with respect to the provided masks.

Nevertheless, all configurations achieve IoUs around 95–96% on this external dataset, underscoring the robustness of the proposed pipeline. From a practical perspective, the LightGBM-refined predictions may be particularly valuable not for maximizing IoU on CVRG-Pano, but for upgrading the quality of its sky annotations by supplying more accurate, high-resolution sky–obstacle boundaries.

4.5. End-to-End Runtime Performance on CPU and GPU

We evaluated the runtime of the main components of the segmentation pipeline for EfficientNet-b4, b5, b6, and b7 backbones. For each model, we measured the total time required for all CNN forward passes across the three input resolutions used in our pipeline (512 × 512, 1024 × 1024, and 2048 × 2048), together with the time spent on handcrafted feature extraction and subsequent LightGBM inference. All timings are averaged over 42 fisheye images of size 1024 × 1024. CPU experiments were performed on an Intel Core i5-1335U (1.3 GHz). For GPU measurements, CNN inference was executed on an NVIDIA H100 (80 GB VRAM) hosted in a server with an AMD EPYC 9124 (3 GHz), while feature extraction and LightGBM inference remained CPU-bound. The full set of results is reported in

Table 8.

On the CPU-only configuration, the end-to-end latency ranges from 16.8 s (EfficientNet-b4) to 30.7 s (EfficientNet-b7). The CNN stage accounts for more than 90% of this cost and is itself dominated by the 2048 × 2048 forward pass, which represents roughly 70–80% of the total CNN runtime. For comparison, a single 1024 × 1024 CNN forward pass requires only 2.8–5.6 s on CPU, so the complete multi-scale + LightGBM pipeline is approximately 5–6× slower than a single-resolution prediction. This highlights the computational price of the improved accuracy obtained with multi-scale inference and post-processing.

On the GPU configuration, multi-scale CNN inference becomes inexpensive, with total forward times between 0.33 s and 0.50 s depending on the backbone. A single 1024 × 1024 CNN pass on the H100 requires only 0.06–0.12 s, illustrating the lower bound achievable on high-end accelerators. However, the overall runtime (2.4–2.8 s) is dominated by CPU-side feature extraction and LightGBM inference, whose performance depends primarily on the host CPU rather than on the GPU. As a result, differences between backbones shrink to only a few hundred milliseconds, making the most accurate model (EfficientNet-b7) essentially cost-neutral on GPU. In contrast, on CPU-only systems, smaller backbones such as b4 or b5 offer a more favorable accuracy–latency trade-off while retaining strong segmentation performance.