Camera-in-the-Loop Realization of Direct Search with Random Trajectory Method for Binary-Phase Computer-Generated Hologram Optimization

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Direct Search with a Random Trajectory Method

3. Experimental Verification of the Method

3.1. Optical Setup

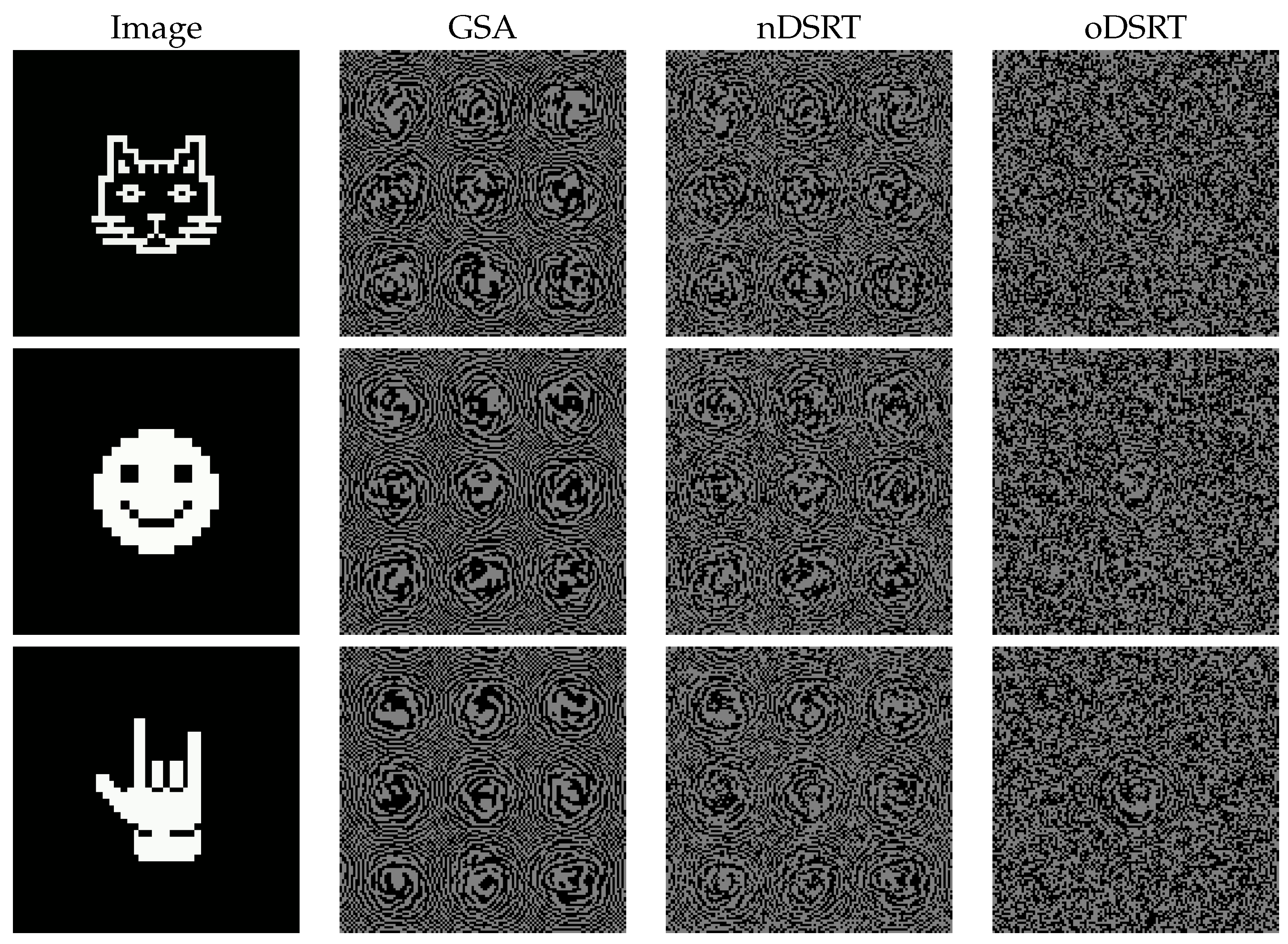

3.2. Three-Stages Algorithm Implementation

3.3. Two-Stage Algorithm Implementation

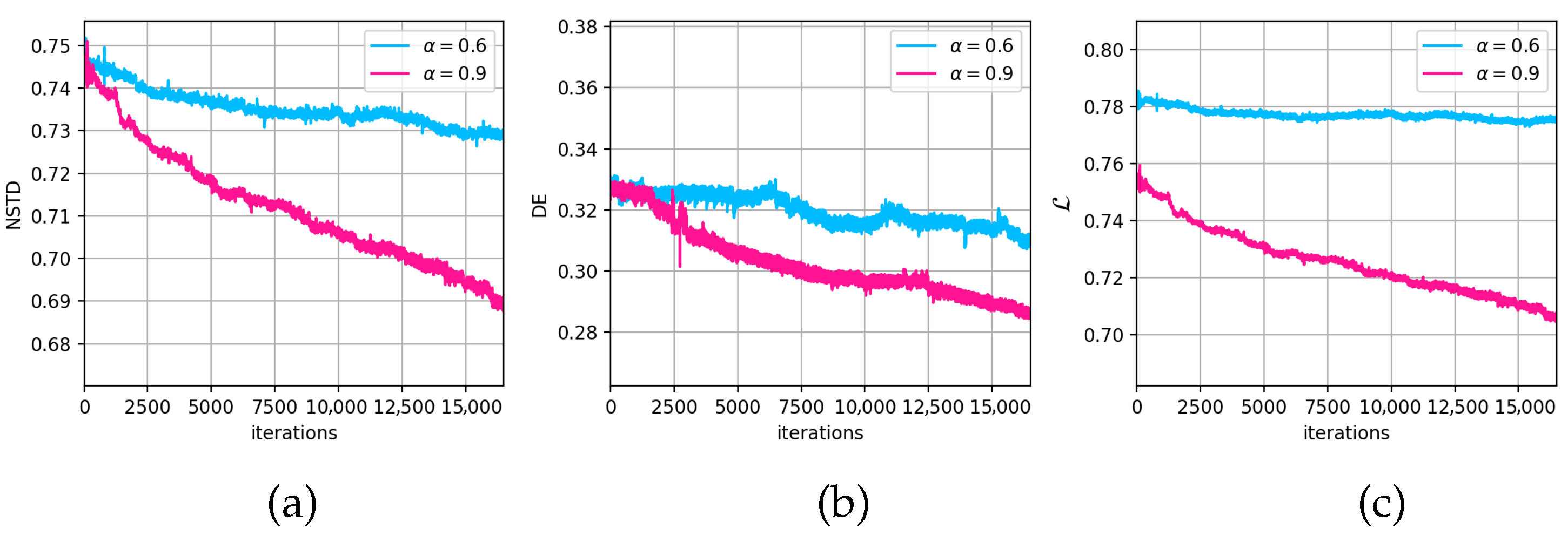

3.4. Parameter Selection in the oDSRT Stage

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- CITL implementation of the DSRT method enabled quality improvement in the restored holographic images of up to 32% by means of NSTD, up to 200% by means of SSIM, and up to 8 dB by means of PSNR, compared to purely numerically synthesized and optimized binary-phase CGH models. In the numerical stages of the proposed algorithms, an idealized model of the optical system was used, ignoring such optical system imperfections as aberrations and readout beam non-uniformity.

- Using a three-stage CGH synthesis algorithm, including the numerical implementation of GSA, followed by numerical and optical implementations of the DSRT method, produced CGH models with a diffraction efficiency of up to 19% higher than that of models synthesized using a two-stage algorithm, which included only the numerical implementation of GSA and the optical implementation of DSRT. However, the improvements in reconstruction quality by means of the NSTD, SSIM, and PSNR were insufficient, amounting to only 2–4%.

- Selecting the target function parameter closer to 1.0 during the implementation of the oDSRT stage leads to a faster decay of the target function value.

- Implementing the DSRT method by means of the CITL approach for CGH models with a resolution of up to pixels using modern high-resolution binary-phase modulators, such as the FLCOS SLMs, has the potential to reduce the computational load by up to two orders of magnitude compared to the purely numerical implementation of the DSRT method. However, this requires a high-speed camera with a larger pixel pitch.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CGH | Computer-generated hologram |

| SLM | Spatial light modulator |

| LCOS | Liquid crystal on silicon |

| FLCOS | Ferroelectric liquid crystal on silicon |

| DMD | Digital micro-mirror device |

| GSA | Gerchberg–Saxton algorithm |

| DSRT | Direct search with random trajectory |

| NSTD | Normalized standard deviation |

| DE | Diffraction efficiency |

| CITL | Camera-in-the-loop |

| NBP | Numeric backward propagation |

| NIR | Numeric image reconstruction |

| FFT | Fast Fourier transformation |

| PC | Personal computer |

| CMOS | Complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor |

References

- Matsushima, K. Introduction to Computer Holography; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.F.; Zheng, H.D.; Yu, Y.J. Holographic Three-Dimensional Imaging of Terra-Cotta Warrior Model Using Fractional Fourier Transform. J. Imaging 2019, 5, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Lee, B. Holographic techniques for augmented reality and virtual reality near-eye displays. Light Adv. Manuf. 2022, 3, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odinokov, S.; Zlokazov, E.; Donchenko, S.; Verenikina, N. Optical memory system based on incoherent recorder and coherent reader of multiplexed computer generated one-dimensional Fourier transform hologram. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2017, 56, 09NA02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cviljušac, V.; Brkić, A.L.; Sviličić, B.; Čačić, M. Computer-generated hologram manipulation and fast production with a focus on security application. Appl. Opt. 2022, 61, B43–B49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlokazov, E.Y.; Kolyuchkin, V.V.; Lushnikov, D.S.; Smirnov, A.V. Computer-Generated Holograms Application in Security Printing. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetzstein, G.; Ozcan, A.; Gigan, S.; Fan, S.; Englund, D.; Soljačić, M.; Denz, C.; Miller, D.A.B.; Psaltis, D. Inference in artificial intelligence with deep optics and photonics. Nature 2020, 588, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, H.; Yamamoto, K.; Ichihashi, Y.; Senoh, T. Image Size Scalable Full-parallax Coloured Three-dimensional Video by Electronic Holography. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 4000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlokazov, E. Methods and algorithms for computer synthesis of holographic elements to obtain a complex impulse response of optical information processing systems based on modern spatial light modulators. Quantum Electron. 2020, 50, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucente, M. Interactive computation of holograms using a look-up table. J. Electron. Imaging 1993, 2, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsueh, C.K.; Sawchuk, A.A. Computer-generated double-phase holograms. Appl. Opt. 1978, 17, 3874–3883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrizon, V.; de-la Llave, D.S. Double-phase holograms implemented with phase-only spatial light modulators: Performance evaluation and improvement. Appl. Opt. 2002, 41, 3436–3447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Chang, C.; Xia, J. Speckleless holographic display by complex modulation based on double-phase method. Opt. Express 2016, 24, 30368–30378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.H. Sampled Fourier Transform Hologram Generated by Computer. Appl. Opt. 1970, 9, 639–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burckhardt, C.B. A Simplification of Lee’s Method of Generating Holograms by Computer. Appl. Opt. 1970, 9, 1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goorden, S.A.; Bertolotti, J.; Mosk, A.P. Superpixel-based spatial amplitude and phase modulation using a digital micromirror device. Opt. Express 2014, 22, 17999–18009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoneda, N.; Saita, Y.; Komuro, K.; Nobukawa, T.; Nomura, T. Transport-of-intensity holographic data storage based on a computer-generated hologram. Appl. Opt. 2018, 57, 8836–8840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zlokazov, E.Y. Transparency function presentation of computer generated Fourier holograms for complex data page restoration. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2019, 58, SKKD04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evtikhiev, N.; Zlokazov, E.; Starikov, S.; Shaulskiy, D.; Starikov, R. Invariant correlation filter with linear phase coefficient holographic realization in 4-F correlator. Opt. Eng. 2011, 50, 065803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerchberg, R.W.; Saxton, W.O. A Practical Algorithm for the Determination of Phase from Image and Diffraction Plane Pictures. Optik 1972, 35, 237–246. [Google Scholar]

- Seldowitz, M.A.; Allebach, J.P.; Sweeney, D.W. Synthesis of digital holograms by direct binary search. Appl. Opt. 1987, 26, 2788–2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondareva, A.P.; Cheremkhin, P.A.; Evtikhiev, N.N.; Krasnov, V.V.; Rodin, V.G.; Starikov, S.N. Increasing quality of computer-generated kinoforms using direct search with random trajectory method. In Proceedings of the Optics and Photonics for Information Processing VIII, San Diego, CA, USA, 17–21 August 2014; Awwal, A.A.S., Iftekharuddin, K.M., Matin, M.A., Márquez, A., Eds.; International Society for Optics and Photonics, SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2014; Volume 9216, p. 92161J. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Lee, B.; Li, N.N.; Chae, M.; Wang, D.; Wang, Q.H.; Lee, B. Multi-depth hologram generation using stochastic gradient descent algorithm with complex loss function. Opt. Express 2021, 29, 15089–15103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheremkhin, P.A.; Evtikhiev, N.N.; Krasnov, V.V.; Starikov, R.S.; Zlokazov, E.Y. Iterative synthesis of binary inline Fresnel holograms for high-quality reconstruction in divergent beams with DMD. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2022, 150, 106859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimobaba, T.; Blinder, D.; Birnbaum, T.; Hoshi, I.; Shiomi, H.; Schelkens, P.; Ito, T. Deep-Learning Computational Holography: A Review. Front. Photonics 2022, 3, 854391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goi, H.; Komuro, K.; Nomura, T. Deep-learning-based binary hologram. Appl. Opt. 2020, 59, 7103–7108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Leng, J.; Dai, P.; Wang, C. DSCCNet for high-quality 4K computer-generated holograms. Opt. Express 2025, 33, 13733–13747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ovchinnikov, A.S.; Krasnov, V.V.; Cheremkhin, P.A.; Rodin, V.G.; Savchenkova, E.A.; Starikov, R.S.; Evtikhiev, N.N. What Binarization Method Is the Best for Amplitude Inline Fresnel Holograms Synthesized for Divergent Beams Using the Direct Search with Random Trajectory Technique? J. Imaging 2023, 9, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, D.S.; Naik, D.N.; Singh, R.K.; Takeda, M. Laser speckle reduction by multimode optical fiber bundle with combined temporal, spatial, and angular diversity. Appl. Opt. 2012, 51, 1894–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Jo, Y.; Nam, S.W.; Chae, M.; Chun, C.; Kim, Y.; Jeong, Y.; Lee, B. Speckle reduced holographic display system with a jointly optimized rotating phase mask. Opt. Lett. 2024, 49, 5659–5662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreev, A.L.; Andreeva, T.B.; Kompanets, I.N.; Zalyapin, N.V. Space-inhomogeneous phase modulation of laser radiation in an electro-optical ferroelectric liquid crystal cell for suppressing speckle noise. Appl. Opt. 2018, 57, 1331–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, D.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Pang, Z.; Chang, S.; Zhang, J.; Wang, B. Spatiotemporal multiplexing for holographic display with multiple planar aligned spatial-light-modulators. Opt. Express 2014, 22, 15791–15803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Yoo, D.; Jeong, J.; Lee, S.; Lee, D.; Lee, B. Wide-angle speckleless DMD holographic display using structured illumination with temporal multiplexing. Opt. Lett. 2020, 45, 2148–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, B.; Kim, D.; Lee, S.; Chen, C.; Lee, B. High-contrast, speckle-free, true 3D holography via binary CGH optimization. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, M.; Saita, Y.; Nomura, T. Improvement of image quality by intensity compensation based on temporal multiplexing in a binary phase-only holographic display. Appl. Opt. 2025, 64, 7779–7786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, D.; Ye, Y.; Cheng, K.; Gu, M.; Fang, X. Temporal multiplexing complex amplitude holography for 3D display with natural depth perception. Opt. Lett. 2025, 50, 1160–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Chen, J.; Yao, J.; Chu, D. A scalable diffraction-based scanning 3D colour video display as demonstrated by using tiled gratings and a vertical diffuser. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 44656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, A.F.; Rukin, I.; Falldorf, C.; Bergmann, R.B. Multicolor Holographic Display of 3D Scenes Using Referenceless Phase Holography (RELPH). Photonics 2021, 8, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sando, Y.; Barada, D.; Yatagai, T. Aerial holographic 3D display with an enlarged field of view by the time-division method. Appl. Opt. 2021, 60, 5044–5048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Choi, S.; Padmanaban, N.; Wetzstein, G. Neural holography with camera-in-the-loop training. ACM Trans. Graph. 2020, 39, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeom, H.J.; Hong, K.; Park, M. High-quality phase-only Fourier hologram generation with camera-in-the-loop. Opt. Express 2025, 33, 6615–6628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Seo, D.W.; In, C.; Min, S.W. Phase-assisted camera-in-the-loop hologram optimization with Fourier aperture function constraint. Opt. Express 2025, 33, 21413–21424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerov, A.A.; Ovchinnikov, A.S.; Cheremkhin, P.A.; Starikov, R.S.; Shifrina, A.V.; Zlokazov, E.Y.; Evtikhiev, N.N. Enhancing iterative hologram generation by mutual accounting quantitative metrics. J. Opt. 2025, 27, 055703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minikhanov, T.Z.; Zlokazov, E.Y.; Starikov, R.S.; Cheremkhin, P.A. Phase modulation time dynamics of the liquid-crystal spatial light modulator. Meas. Tech. 2024, 66, 935–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkov, A.A.; Minikhanov, T.Z.; Zlokazov, E.Y.; Shifrina, A.V.; Petrova, E.K.; Starikov, R.S. Characteristics of temporal dynamics of liquid crystal spatial modulators as a limitation of the performance of tunable diffractive neural networks. Meas. Tech. 2025, 74, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Object | NSTD | DE | SSIM | PSNR [dB] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| “smile” | 0.47 | 0.37 | 0.53 | 24.1 |

| “rock” | 0.54 | 0.34 | 0.44 | 22.9 |

| NSTD | DE | SSIM | PSNR [dB] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSA | 0.75 | 0.33 | 0.51 | 25.7 |

| oDSRT () | 0.73 | 0.31 | 0.57 | 27.2 |

| oDSRT () | 0.69 | 0.29 | 0.61 | 28.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zlokazov, E.Y.; Starikov, R.S.; Cheremkhin, P.A.; Minikhanov, T.Z. Camera-in-the-Loop Realization of Direct Search with Random Trajectory Method for Binary-Phase Computer-Generated Hologram Optimization. J. Imaging 2025, 11, 434. https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging11120434

Zlokazov EY, Starikov RS, Cheremkhin PA, Minikhanov TZ. Camera-in-the-Loop Realization of Direct Search with Random Trajectory Method for Binary-Phase Computer-Generated Hologram Optimization. Journal of Imaging. 2025; 11(12):434. https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging11120434

Chicago/Turabian StyleZlokazov, Evgenii Yu., Rostislav S. Starikov, Pavel A. Cheremkhin, and Timur Z. Minikhanov. 2025. "Camera-in-the-Loop Realization of Direct Search with Random Trajectory Method for Binary-Phase Computer-Generated Hologram Optimization" Journal of Imaging 11, no. 12: 434. https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging11120434

APA StyleZlokazov, E. Y., Starikov, R. S., Cheremkhin, P. A., & Minikhanov, T. Z. (2025). Camera-in-the-Loop Realization of Direct Search with Random Trajectory Method for Binary-Phase Computer-Generated Hologram Optimization. Journal of Imaging, 11(12), 434. https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging11120434