3. Models and Methods

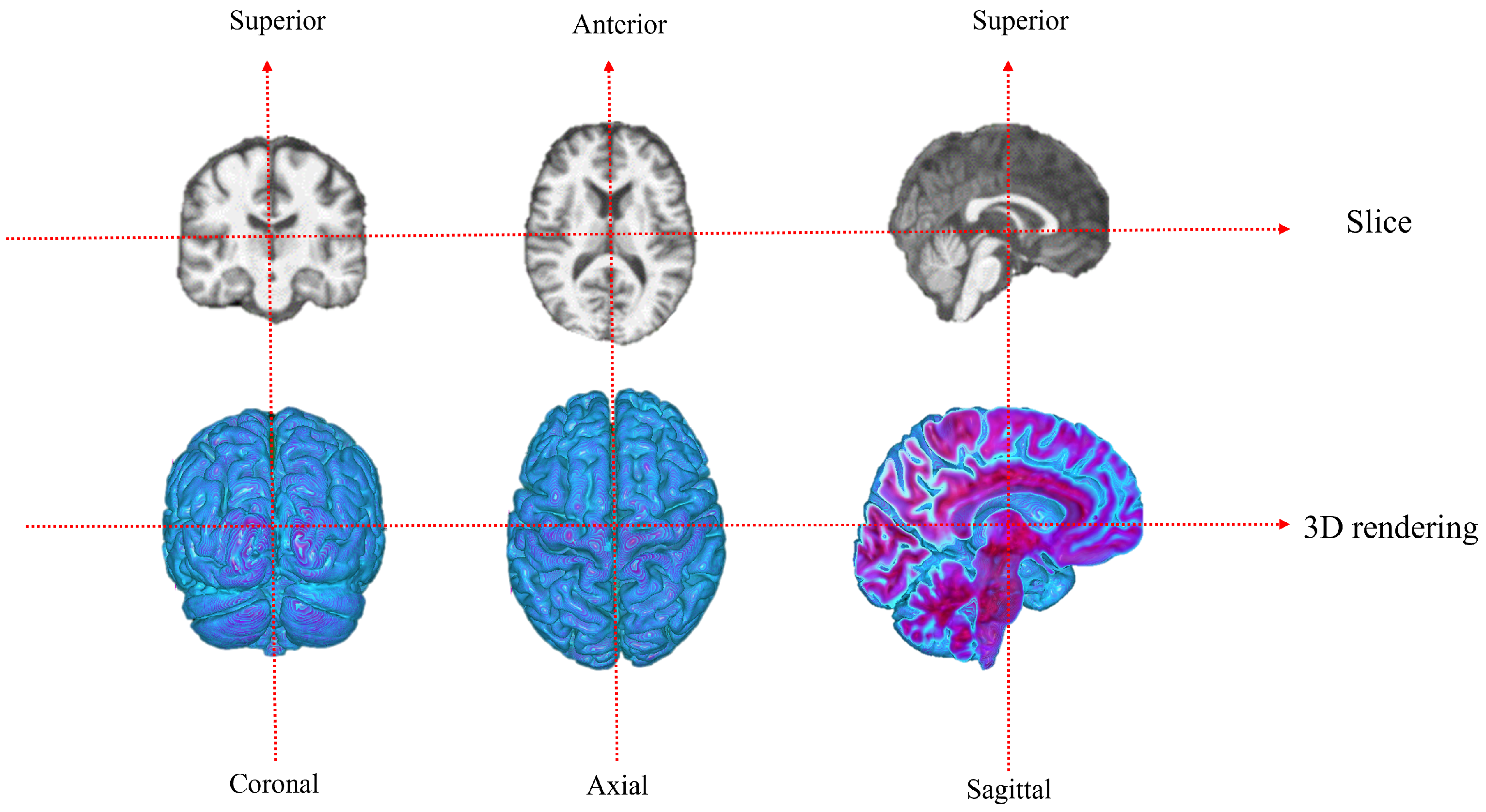

MRI provides a non-invasive way to visualize brain structural features. The neuron density and spin density of brain tissues affect the MRI signal intensity, which is captured as a series of 2D slices forming a 3D volume. Each voxel corresponds to a specific spatial location, and its intensity reflects the local signal strength, typically normalized to ensure consistency across subjects. The preprocessed 3D MRI data serve as input to a CNN. The CNN extracts local spatial features through convolutional layers and enhances nonlinear representations via activation functions. The features are then flattened and fed into fully connected layers for classification, enabling the network to learn discriminative patterns from MRI scans for Alzheimer’s disease identification.

In medical image analysis, binary classification plays a fundamental role in distinguishing between different clinical conditions, such as separating patients with cognitive impairment from healthy controls. Compared to multi-class classification, binary classification tasks are often more practical in clinical settings, as they focus on specific diagnostic objectives and help clinicians make clearer decisions. However, deep learning models used for binary classification in medical imaging typically require large computational resources (For example, training a 3D CNN with millions of parameters may require GPUs such as NVIDIA RTX 4090 (24 GB VRAM) and several hours of computation per epoch.), which may limit their applicability in real-world scenarios where efficiency and deployment on limited hardware are essential. To address this challenge, lightweight models have gained increasing attention, as they reduce computational cost and memory usage while maintaining competitive accuracy, making them more suitable for clinical applications.The lightweight binary classification framework we designed is as follows:

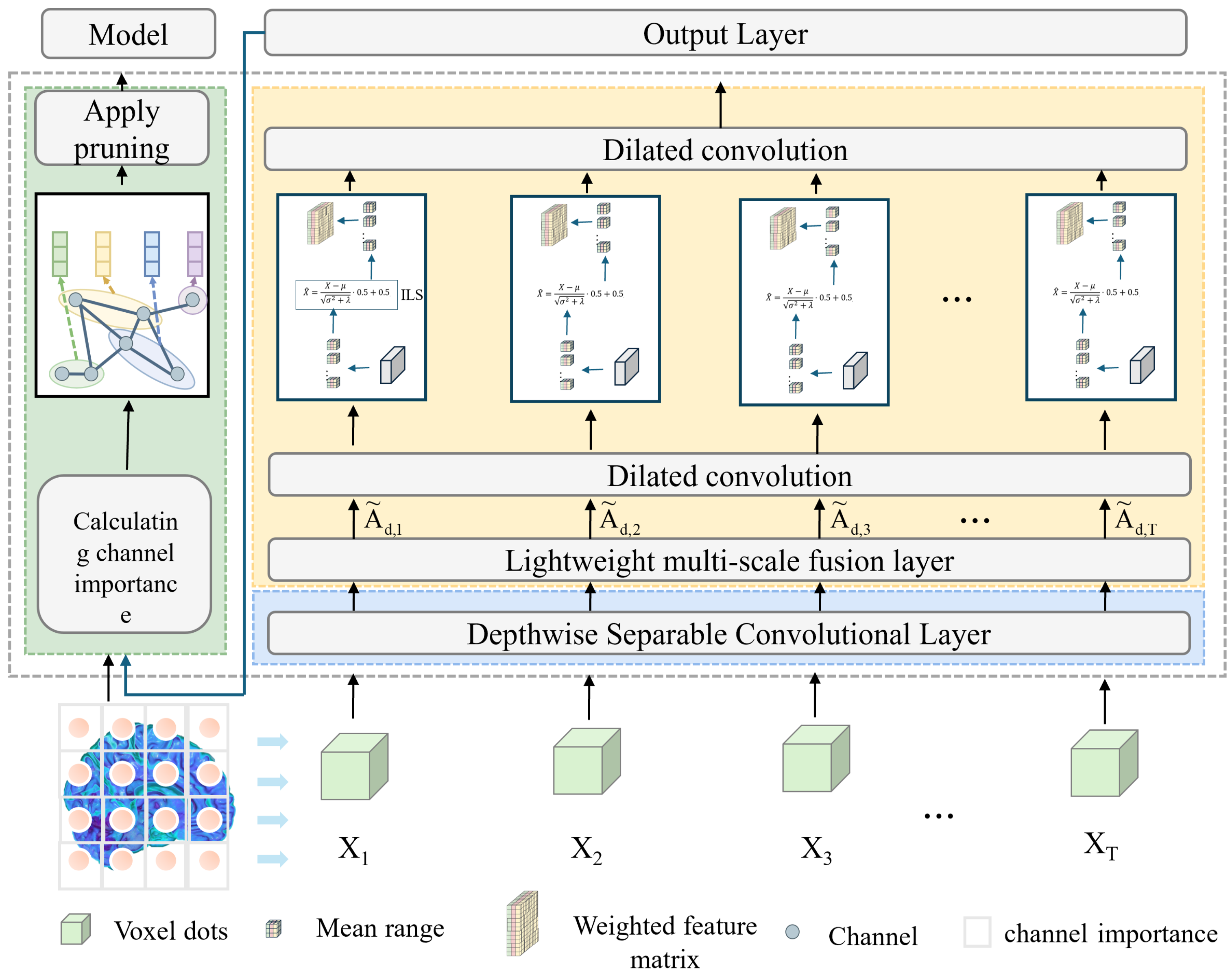

The workflow of the proposed model begins with the loading and preprocessing of three-dimensional MRI data, where the input is a single-channel volumetric image. A 1 × 1 × 1 convolution layer is first employed for channel mapping and preliminary feature extraction, which reduces computational complexity while enhancing representation capacity. Subsequently, a Depthwise Separable Conv3D is introduced, in which spatial and channel convolutions are decoupled. This design significantly decreases the number of parameters and computational cost, while retaining the ability to capture local spatial patterns. To further strengthen feature representation, a lightweight multi-scale fusion module (LMF) block is integrated in the intermediate layers. Within this module, multi-scale convolutional branches with kernels of 3 × 3 × 3 and 5 × 5 × 5 operate in parallel to extract features under different receptive fields, followed by a Improved and lightweight channel attention mechanism that adaptively reweights and fuses these features, thereby enabling effective multi-scale information integration. The selection of 3 × 3 × 3 and 5 × 5 × 5 convolution kernels is based on experimental evidence that these kernel sizes provide the best trade-off between precision and efficiency. Smaller kernels (e.g., 1 × 1 × 1) tend to lose spatial detail, while larger ones (e.g., 7 × 7 × 7) greatly increase the computational burden. As demonstrated in

Table 1 and

Table 2, the combination of 3 × 3 × 3 and 5 × 5 × 5 achieves the optimal balance, maintaining high classification accuracy while ensuring the model remains lightweight. This design choice effectively supports real-time applicability without sacrificing representational capacity. At higher semantic stages, dilated convolutions are incorporated to expand the receptive field and capture richer contextual information without increasing the parameter count. In parallel, an improved lightweight Similarity-Aware Attention Module (SimAM), referred to as ILS, is adopted to model feature energy, thereby enhancing fine-grained discriminative features while suppressing redundancy. Finally, compact and discriminative feature representations are obtained through global average pooling and a fully connected layer, ensuring a balance between lightweight design and classification performance. As shown in

Figure 1.

In deep learning frameworks utilizing MRI data, the intermediate representations are essential for precise classification outcomes [

23]. To effectively model both detailed anatomical structures and broad contextual information in 3D brain volumes, we propose the LMF module. It combines multi-scale convolutional operations, hierarchical feature integration, and adaptive channel weighting to automatically emphasize the most relevant anatomical regions. Through the joint use of local and global cues, the LMF design enhances the model’s sensitivity to minor pathological variations—such as cortical thinning and hippocampal shrinkage—thereby improving diagnostic performance without increasing computational cost.

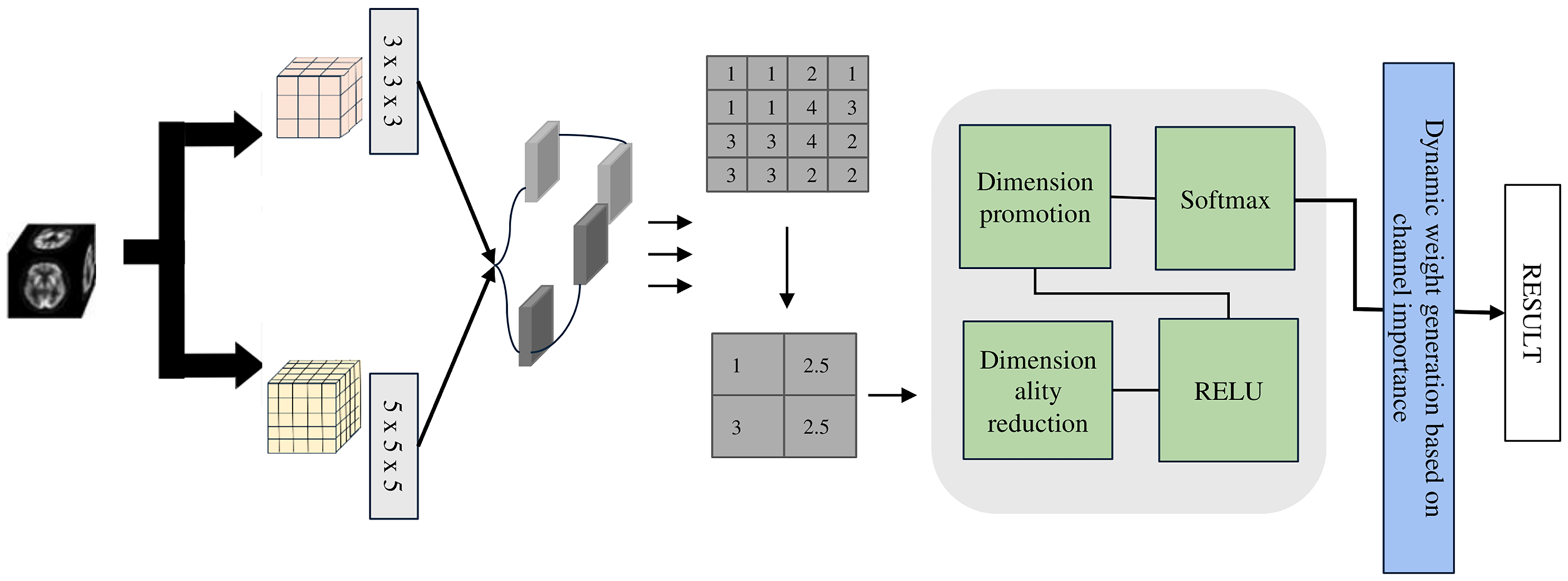

The LMF module (see

Figure 2), developed based on extensive experiments (see

Table 1) with multi-scale convolutions, employs parallel 3 × 3 × 3 and 5 × 5 × 5 depthwise separable convolution kernels to balance model lightweightness and classification accuracy. Depthwise separable convolutions separate spatial and channel-wise operations, providing a 1 × 1 × 1 receptive field while significantly reducing the number of parameters and computational cost, thus achieving a lightweight design. Specifically, the 1 × 1 × 1 convolution is used for channel information integration and efficient feature transformation, while the 3 × 3 × 3 and 5 × 5 × 5 convolutions capture medium- and large-scale structural features, respectively.

Specifically, the depthwise separable 3D convolution establishes the lightweight foundation of the model, and its formulation is expressed as follows:

where

c denotes the channel,

represents the receptive field of the convolution kernel, and

corresponds to the convolution kernel of the c channel,

represents the point-by-point convolution weight, which is used for cross-channel information fusion. Equation (

1) represents performing a convolution on the input feature map

at spatial position

p over a local neighborhood defined by the offset

q, producing an intermediate feature

. Equation (

2) linearly combines the intermediate features

across all channels using weights

, achieving channel-wise fusion and resulting in the final output feature

. In short, the first represents spatial convolution, while the second represents channel fusion.

In the LMF block, we use different convolution kernels (For example, 1 × 1 × 1, 3 × 3 × 3, and 5 × 5 × 5 kernels extract multi-scale features across channels) to extract features in parallel. The formula can be written as:

where

represents convolution kernels of different sizes,

S is the number of scales, and the output

represents multi-scale features. After obtaining the multi-scale features, they are concatenated and globally pooled, followed by feature reweighting through our designed lightweight adaptive weighting module, and its formulation is expressed as follows:

Equation (

4) represents concatenating multiple 3D feature maps

along the channel dimension, and then computing the average over the entire spatial dimensions (Depth

D, Height

H, Width

W), i.e., 3D global average pooling, to obtain a global feature for each channel. For example, for a feature map of size

, after concatenating two features, the number of channels at each position becomes 2. Averaging over all

positions yields a vector

z of length 2, representing the globally pooled channel features.

The Equation (

5) indicates that the input vector

z is first linearly transformed and passed through an activation function, and then Softmax converts the result into a probability distribution. The input can be any real-valued vector, and the output gives probabilities for each element summing to 1. For example, applying Softmax to the scores

results in

, indicating the first class has the highest predicted probability.

where

is the ReLU(Rectified Linear Unit) activation function, and

represents the fusion weights of multi-scale features.

The core idea of ILS is to model feature importance through an energy function and normalize it using Sigmoid. Its attention weight formula is:

Compared to traditional SimAM, we omit the explicit energy function and instead adopt a normalization and translation scaling approach to stabilize the numerical distribution, and obtain weights through Sigmoid activation. This not only avoids additional steps in energy calculation but also ensures a more balanced feature distribution across different scales. its formulation is expressed as follows:

represents the values of the input feature map at spatial positions ; are the mean and variance of the channel, respectively; is a smoothing term used to avoid zero division; is the Sigmoid function; M is the attention mask, Y is the weighted output, is the normalized feature map, and the range is shifted and scaled to around .

The expansion convolution of the last two layers is used to expand the receptive field, and its formula is:

Equation (

9) defines the 3D dilated convolution operation. Specifically,

denotes the input 3D feature map, where

d,

h, and

w represent the depth, height, and width indices, respectively. The convolution kernel weights are denoted by

at offset

, and

r indicates the dilation rate that controls the spacing between kernel elements. For example, when using a

kernel with a dilation rate of

, each output voxel

is obtained by performing element-wise multiplication between the corresponding

region of the input

x and the kernel weights

w, followed by summation. This operation enables the model to capture local spatial dependencies in 3D volumetric data.

In order to make the model more lightweight, we introduce the asymptotic pruning method, which sets the redundant channels of the model to zero during training. The threshold projection formula for pruning is as follows:

Among them, W is the weight arranged by the convolutional layer according to the output channel (corresponding one-to-one to the corresponding BatchNorm (BN) channel), corresponds to the channel scaling parameter vector. The uantile of BN is used such that channels with a proportion r satisfying are pruned. is the indicator function: it takes 1 if the condition is met, otherwise 0. ⊙ represents element-wise multiplication broadcasted by channel.

4. Materials and Experiments

The experiments were conducted in a Python 3.9 environment with PyTorch 2.1 and CUDA 11.8 on a high-performance computing platform equipped with an NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU (24 GB; NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and an Intel Core i9-14900 processor (Intel Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

The model employs a 3D convolutional network architecture and was trained for a total of 100 epochs. Each batch contains 4 samples, and gradient accumulation is applied to achieve an effective batch size of 16, balancing memory usage and training stability. The loss function is Label Smoothing Cross-Entropy LabelSmoothingLoss, smoothing = 0.1), and a sparsity regularization on BatchNorm () is applied to constrain model complexity and enhance lightweight efficiency. The optimizer is SGD (Stochastic Gradient Descent) with a learning rate of , momentum of , and weight decay of , while a ReduceLROnPlateau scheduler adjusts the learning rate according to the training loss. Progressive pruning is performed every 5 epochs (prune ratio per step ) to remove redundant channels and further compress the model. During training, both training and validation losses and accuracies are recorded, and a checkpoint of the model is saved at the end of each epoch to ensure reproducibility while maintaining model performance.

The dataset we are using is from Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI), The ADNI is one of the most representative and influential publicly available databases for Alzheimer’s disease research. Launched in the United States in 2004, its goal is to promote early diagnosis and intervention of AD through multi-center, multi-modal longitudinal studies. The dataset includes a wide range of multimodal data from diverse participants, such as structural MRI, functional MRI, PET imaging, genetic information, biomarkers, and clinical assessment scales, covering individuals across different stages including NC, MCI, and AD. ADNI not only provides standardized, high-quality data resources for clinical research but also serves as an important platform for developing and validating machine learning and deep learning methods in early diagnosis and progression prediction of AD.

The ADNI database offers preprocessed MRI data to ensure consistency and reliability in subsequent analyses. In this work, several key preprocessing steps were applied to the acquired images. First, co-registration was used to align scans from different sessions or imaging modalities into a unified coordinate space, minimizing positional variations. Frame averaging was then performed to suppress random noise and enhance the signal-to-noise ratio by merging multiple acquisitions into a single image. Standardization converted all images to a uniform resolution and format, enabling cross-subject comparison. AC–PC correction adjusted brain orientation along the anterior commissure–posterior commissure axis, ensuring anatomical alignment across participants. Intensity normalization further rescaled voxel values to reduce scanner- or protocol-related variability. Skull stripping removed non-brain tissues such as scalp and skull, improving the accuracy of brain structure analysis. Finally, Gaussian smoothing was applied to suppress high-frequency noise and emphasize subtle structural differences by further enhancing signal quality.

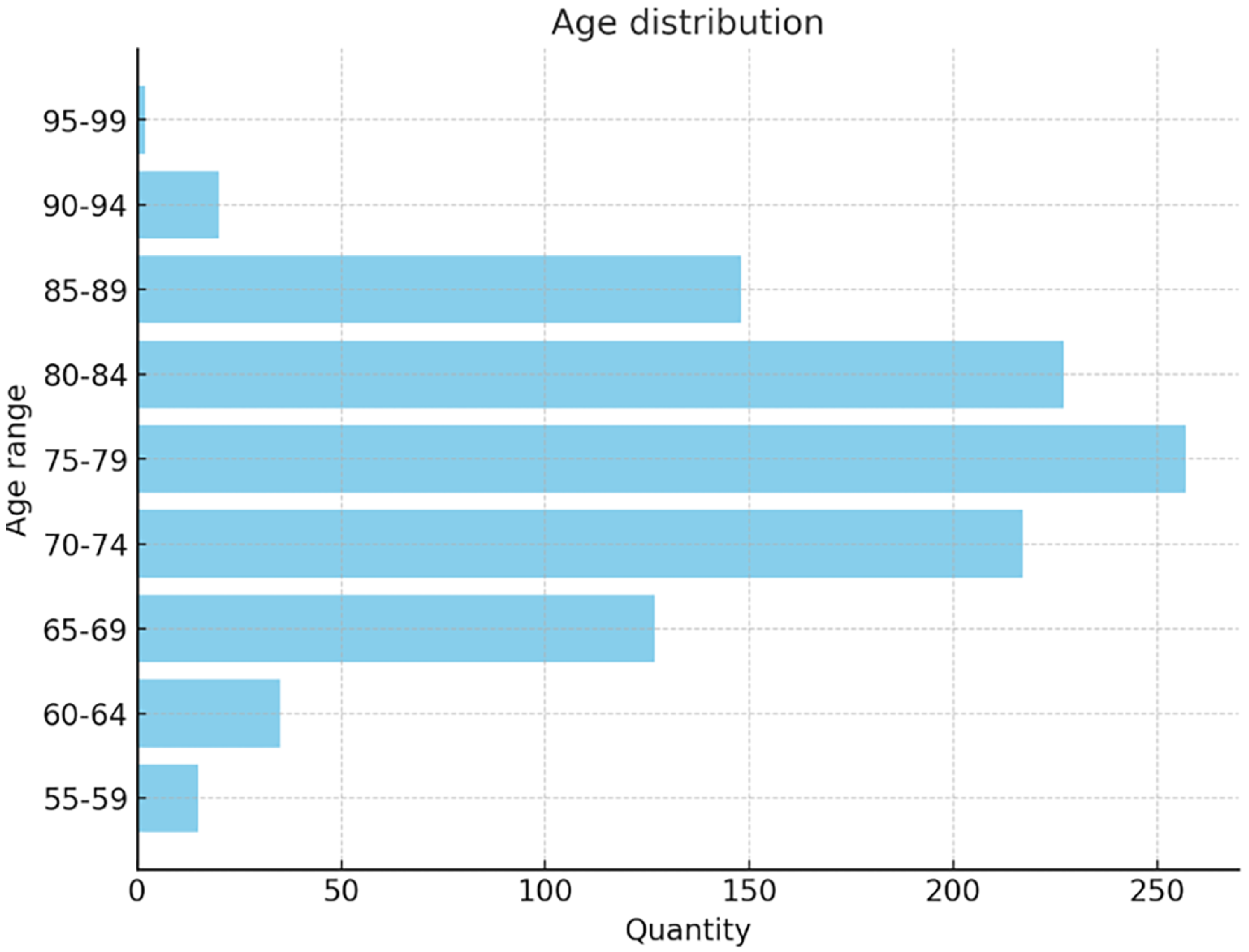

The dataset used in this study includes 1012 participants (555 males and 457 females, aged 55–90), covering a broad spectrum of cognitive conditions. A total of 2174 MRI images were classified into AD (443), MCI (365), and NC (1366), The age distribution in the dataset is shown in

Figure 3:

The 3D rendering three views of the dataset are shown in

Figure 4:

To address the issue of data imbalance, several complementary strategies were employed to enhance model generalization and minimize bias toward dominant categories. These included a five-fold cross-validation scheme, synthetic sample generation, and balanced resampling.

During the five-fold validation process, the dataset was partitioned into five equal subsets, and the training procedure was repeated five times. In each iteration, one subset served as the testing set, while the remaining subsets were used for model training and validation.

To ensure balanced learning, oversampling of minority classes was performed to equalize class distributions, and data augmentation was applied to further expand the training set. Given the volumetric characteristics of 3D MRI data, strong spatial transformations—such as large rotations or translations—were avoided, as they could distort structural integrity and destabilize the network. Instead, mild yet effective augmentations, including Gaussian noise injection and gamma correction, were adopted.

By integrating cross-validation, balanced resampling, and augmentation, the proposed approach effectively mitigated class imbalance and improved the reliability, robustness, and stability of the model evaluation process.

To evaluate the model’s lightweight characteristics, we selected four indicators from three core dimensions: structure, computation, and storage. These include the Number of Parameters, FLOPs (Floating Point Operations), Model Size, and Performance Density. The number of parameters reflects the structural complexity of the model, with fewer parameters indicating a more compact and efficient architecture for training and deployment. FLOPs measure the computational cost of a single forward pass, where lower values correspond to faster inference and better suitability for real-time or resource-constrained scenarios. Model size directly represents storage and memory requirements, with smaller sizes facilitating deployment on embedded or mobile devices. In addition, Performance Density—defined as the ratio of classification accuracy to the number of parameters—serves as an integrated metric that balances predictive performance and computational efficiency. Together, these four metrics provide a comprehensive evaluation of the model’s lightweight characteristics and its practical applicability in clinical settings.

- 1.

Number of computational parameters (Para)

Measuring the total number of trainable parameters in a model is a fundamental indicator of lightweighting. The formula is as follows:

where

L is the total number of convolutional or fully connected layers,

is the kernel size of the

l-th layer,

are the number of input and output channels of the

l-th layer.

- 2.

Floating Point Operations (FLOPs)

Measure the number of floating-point operations required for a model to perform forward inference once, reflecting the computational complexity. The FLOPs calculation formula for convolutional layers:

Among them, , , are the output feature map sizes; , are the number of input/output channels; , , are the size of the convolution kernel.

- 3.

Model Size (MS)

Measuring the size of storage space or memory occupied by model files directly affects deployment efficiency. The formula is as follows:

b is the number of bytes occupied by each parameter (such as 4 bytes for 32-bit floating-point numbers).

- 4.

Performance Density (PD)

To quantitatively evaluate the trade-off between model performance and complexity, we introduce a metric termed PD, defined as:

where

denotes the classification accuracy (in percentage), and

represents the number of parameters in the model. The PD reflects how much accuracy is achieved per million parameters, serving as a measure of parameter efficiency. Although not a standard metric, it provides an intuitive quantification of the performance–complexity balance. The unit of PD can be interpreted as “% per million parameters (% pm)”, analogous to the “parts per million (ppm)” concept used in spectroscopy. Similar ideas of efficiency metrics have been discussed in prior works such as EfficientNet [

24] and MobileNetV3 [

25].

The classification

is defined as follows:

where

,

,

, and

denote the numbers of true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives, respectively. This metric measures the overall proportion of correctly classified samples in the dataset.

We also selected two other important accuracy indicators in medicine: SEN and SPE to reflect the degree of change with model lightweighting, and F1 score to reflect the handling of dataset imbalance.

- 1.

Sensitivity (SEN)

Measures the ability of the model to correctly identify positive samples, i.e., the proportion of actual positive samples that are correctly predicted:

- 2.

Specificity (SPE)

Measures the ability of the model to correctly identify negative samples, i.e., the proportion of actual negative samples that are correctly predicted:

- 3.

F1 Score

F1 Score is defined as the harmonic mean of two core classification metrics—Precision and Recall. Its primary purpose is to comprehensively evaluate a model’s performance on the positive class, with particular value in scenarios involving imbalanced datasets (e.g., fraud detection, rare disease diagnosis, where positive samples are far fewer than negative ones). Where F1 sore is defined as:

Before performing multi-scale convolution, we need to determine the type and number of convolution kernels, which requires balancing the accuracy and lightweight of multi-scale convolution. Considering the practical goal, we chose the ADvsMCI model, which is more relevant to early classification of Alzheimer’s disease, for the experiment. The experiment is shown in

Table 1 and

Table 2.

It can be observed that the choice of convolution kernels has no significant impact on classification accuracy. In particular, the 1 × 1 × 1 kernel contributes little additional benefit, which may be attributed to the fact that depthwise convolutions inherently provide a receptive field similar to that of a 1 × 1 × 1 kernel, thereby diminishing its effect. In contrast, larger kernels (e.g., 7 × 7 × 7) are capable of capturing broader contextual information but incur a much higher cost in terms of model lightweighting, substantially increasing both parameter count and computational overhead. Taking accuracy and efficiency into account, we removed the 7 × 7 × 7 kernel in our design and replaced it with lightweight dilated convolutions, which expand the receptive field without significantly increasing computational burden. This allows the model to maintain compactness while preserving the representational benefits of larger kernels. As shown in

Table 1 and

Table 2, dilated convolutions achieve the best accuracy while simultaneously meeting lightweighting objectives, thereby validating the effectiveness and practicality of this strategy.

The experiments were conducted using a lightweight 3D CNN model. This model is built around depthwise separable convolutions, with an initial channel size of 24, and integrates multi-scale convolutional kernels ( and ) together with LMF. A parameter-free ILS attention mechanism was further incorporated to enhance feature representation. To achieve model lightweighting, a sparsity regularization term based on BN weights () was added during training, along with a progressive pruning strategy: approximately 5% of less important channels were pruned every 5 epochs.

For the training configuration, the optimizer was SGD with a learning rate of 0.01, momentum of 0.9, and weight decay of . The classification loss function was CrossEntropyLoss (reduction = “mean”), with label smoothing () applied in some experiments to improve generalization. The learning rate scheduling strategy employed ReduceLROnPlateau, which decayed the learning rate by a factor of 0.1 if the validation loss did not decrease for 10 consecutive epochs, with verbose mode enabled for monitoring.

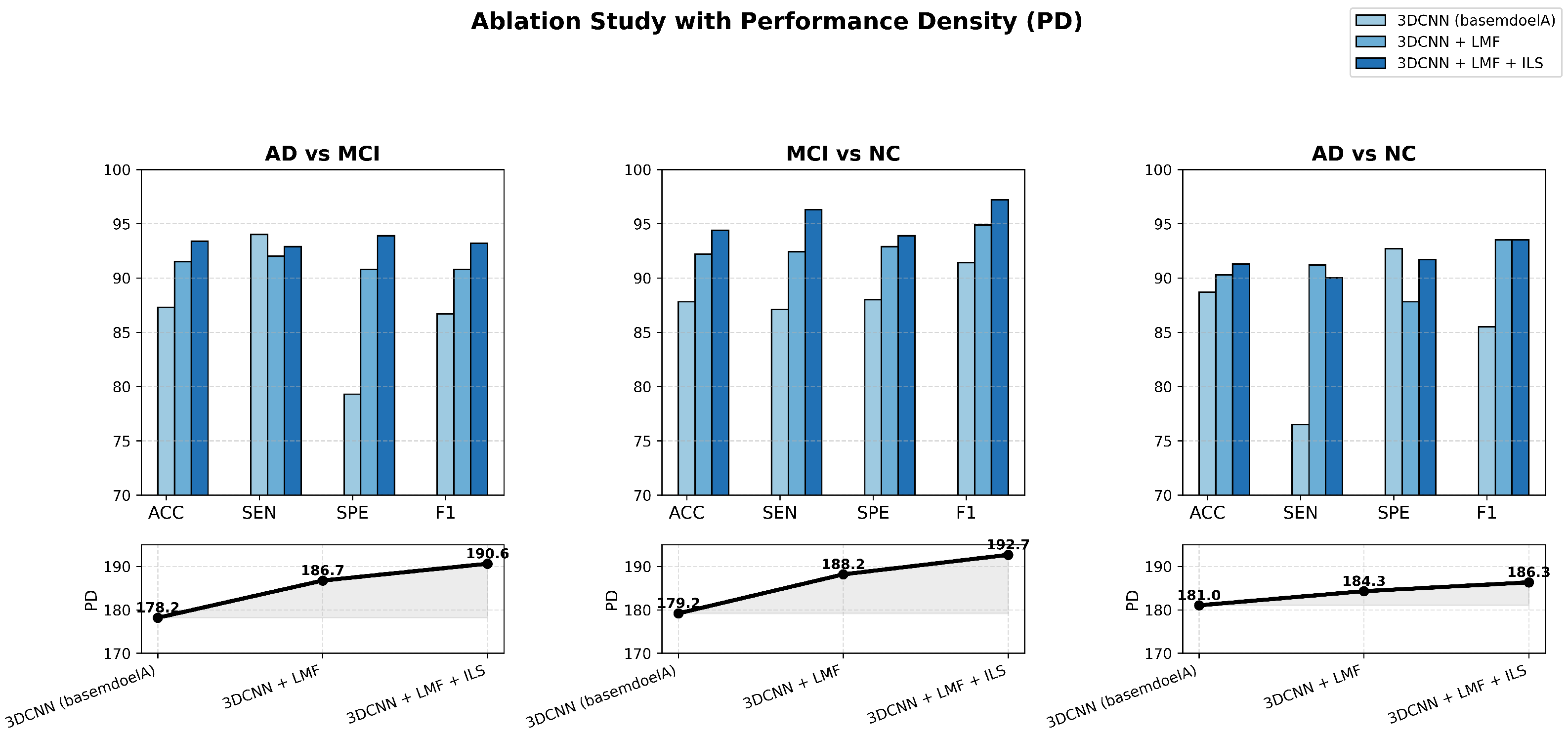

A five-fold cross-validation was performed, and the results of the ablation experiments targeting model lightweighting are reported in

Table 3. The performance density PD, calculated as the average value across the three binary classification tasks (AD vs. MCI, MCI vs. NC, and AD vs. NC), is also included to comprehensively reflect the overall balance between model accuracy and computational efficiency.

As shown in the table, the proposed lightweight strategies significantly reduce the model complexity at different levels. Compared with the original 3DCNN, pruning reduces the number of parameters from 35.39 M to 19.21 M, decreases FLOPs from 311 G to 169 G, and compresses the model size by nearly 46%, indicating that pruning can effectively shrink the network and eliminate redundant computations. By introducing depthwise separable convolution, the parameter count is further reduced to 0.92 M, while FLOPs and model size drop to 8.07 G and 3.51 M, respectively, accounting for only about 2.6% of the basemodelL (remove pruning and depthwise separable convolution), which demonstrates that depthwise convolution makes the most significant contribution to reducing computational and storage overhead. When depthwise separable convolution is combined with pruning, the model reaches its lowest complexity, with only 0.49 M parameters, 4.39 G FLOPs, and a model size of 1.91 M, corresponding to approximately 98.6% reduction compared with the basemodelL. Overall, depthwise convolution serves as the primary driver of model lightweighting, while pruning further removes redundant channels on this basis. The two methods are highly complementary, enabling the model to achieve substantial reductions in computation and storage costs while maintaining stable classification performance. Since the inference latency is closely related to the number of floating-point operations, the drastic reduction in FLOPs from 311 G to 4.39 G directly translates into a significant acceleration in inference. In practical deployment, this reduction corresponds to more than a 70× theoretical speed-up and achieves an average inference time of less than 0.1 s per MRI scan. Such efficiency highlights the model’s excellent real-time applicability, indicating its potential for rapid and scalable clinical screening, even on edge devices or resource-limited systems. Thus, the proposed approach provides a practical solution for brain MRI diagnosis in resource-constrained scenarios.

Moreover, the ratio between model performance and its parameter size, increases sharply with the introduction of lightweight strategies. Specifically, PD rises from 2.61 in the basemodelL model to 189.87 in the combined approach, reflecting that the proposed methods not only reduce computation and storage requirements but also greatly improve the efficiency of parameter utilization.In addition, the accuracy change of the overall lightweight model is shown in

Figure 5.

It can be observed that the basemodelL is located in the upper-left region, with the highest number of parameters and FLOPs, as well as the largest bubble size, indicating the greatest storage and computational cost. The Pruning (P) model significantly reduces the number of parameters and model size while maintaining nearly unchanged accuracy, though the reduction in FLOPs is relatively limited. The Depthwise Convolution (DC) model and the combined DC+P model demonstrate substantial advantages in both FLOPs and parameter reduction, with much smaller bubble sizes that reflect minimal storage requirements; in particular, the DC+P model achieves the optimal lightweight performance. Notably, although different lightweight strategies lead to substantial differences in model complexity, the accuracy remains almost unchanged, suggesting that the proposed approach can achieve considerable compression and acceleration without compromising classification performance.

To further validate the effectiveness and efficiency of the proposed lightweight 3D CNN, ablation experiments were conducted across three binary classification tasks—AD vs. MCI, MCI vs. NC, and AD vs. NC—using MRI data. The results aim to examine the individual and combined contributions of the LMF and ILS modules to model performance and computational efficiency.

Figure 6 presents a comprehensive visualization of these ablation outcomes, where bar charts and PD curves jointly illustrate how each enhancement progressively improves classification accuracy and efficiency while preserving the model’s lightweight nature.

The figure clearly illustrates the ablation results of the proposed lightweight MRI-based Alzheimer’s disease classification model across three comparative tasks: AD vs. MCI, MCI vs. NC, and AD vs. NC. Through bar charts and PD curves, it intuitively demonstrates the progressive improvements achieved as the 3DCNN model successively integrates the LMF and ILS modules, yielding consistent gains in ACC, SEN, SPE, and F1 score.

It is worth noting that our model performs best in MCI vs. NC classification and poorly in AD vs. NC classification. This result can be reasonably explained by the inherent heterogeneity of AD pathology and the subtle but consistent structural alterations observed in MCI. In AD patients, the atrophy pattern varies significantly across individuals, making the discriminative boundary more diffuse. In contrast, MCI subjects exhibit more homogeneous early-stage abnormalities, which can be effectively captured by the proposed LMF and ILS that focus on fine-grained spatial variations. Moreover, the relatively lower PD in AD vs. NC further reflects the higher intra-class variability and complexity of AD data, highlighting the robustness of our model when facing heterogeneous disease patterns.

Across all tasks, the PD values exhibit a stable upward trend from the basemodelA (remove LMF and ILS modules) to the enhanced configurations, confirming that each component contributes to both higher predictive accuracy and improved efficiency. This indicates that the proposed model can maintain strong performance while substantially reducing complexity. For instance, the enhanced model achieves comparable or even better accuracy with fewer parameters and shorter inference time—requiring less GPU memory and computation per scan—thereby clearly demonstrating lower computational cost. Overall, the model achieves an excellent balance between efficiency and precision, validating the effectiveness of the proposed lightweight design.

The ablation results further reveal that the LMF and ILS modules play complementary roles in performance enhancement. LMF captures multi-scale structural information, improving the network’s capacity to distinguish subtle brain pattern variations, while ILS strengthens attention to key lesion regions, enhancing discriminative focus. The improvements are particularly pronounced in the MCI vs. NC classification, indicating the model’s strong potential for early detection of mild cognitive impairment. Overall, the proposed lightweight 3D CNN achieves stable and interpretable gains across all tasks, proving its effectiveness, compactness, and practicality for efficient MRI-based Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis.

Furthermore, the experimental results for SEN and SPE indicate that the issue of dataset imbalance has been effectively mitigated. In classification tasks, if one class has significantly more samples than others, the model tends to be biased toward the majority class, leading to notable discrepancies between SEN and SPE and a decline in overall model performance, particularly for minority classes. By employing strategies such as data augmentation, oversampling, and cross-validation, this study successfully balanced the sample distribution across classes. As a result, the model demonstrates stable recognition performance for all categories, maintaining a high F1 score and further confirming its robustness in handling imbalanced datasets.

To assess whether the proposed model’s improvements over the baseline were statistically significant, a one-sample

t-test was performed. This test evaluates whether the mean accuracy of the proposed model across five cross-validation folds is significantly higher than the baseline average, taking into account the variability of the folds. A

p-value less than 0.05 indicates that the observed improvement is unlikely to occur by chance, the formula for the

t-test is as follows:

where

is the mean accuracy of the proposed model across

n cross-validation folds,

is the baseline model’s average accuracy,

s is the standard deviation of the proposed model’s accuracies across folds, and

n is the number of folds. A

p-value less than 0.05 indicates that the improvement over the baseline is statistically significant, the final results are shown in

Table 4.

The proposed model achieved higher mean accuracies than the baseline across all tasks. Single-sample t-tests show that these improvements are statistically significant (p < 0.01), confirming the model’s consistent robustness.

To further verify the robustness of our model, we also tested it on an external subset of the Open Access Series of Imaging Studies (OASIS) dataset (Includes 204 AD, 243 MCI, and 371 NC.). We used the same preprocessing on the MRI data from OASIS and then directly tested and fine-tuned the model (For each classification, 30 OASIS MIR images are used as input. The preceding convolutional layers are frozen, the final classification head is fine-tuned, and then testing is performed.). The results are shown in

Table 5.

As shown in

Table 5, the model trained on ADNI achieved accuracies of 86.0%, 86.4%, and 87.3% for AD vs. NC, AD vs. MCI, and MCI vs. NC, respectively, when directly tested on OASIS. Compared to the original ADNI test performance (91.3%, 93.4%, and 94.4%), this corresponds to a decrease of approximately 5.3, 7.0, and 7.1 percentage points, which is consistent with typical cross-dataset performance drops reported in the literature [

26]. The decline can be attributed to domain shifts arising from differences in scanning protocols, preprocessing pipelines, and sample distributions.

After fine-tuning the model with a small number of OASIS samples, the accuracies improved to 88.7%, 89.1%, and 89.7%, yielding gains of 2.7, 2.7, and 2.4 percentage points over direct testing. The variations in performance drop among tasks reflect the intrinsic difficulty and feature separability: AD vs. NC has more distinct anatomical differences, resulting in a smaller decline, whereas MCI-involved tasks have subtler distinctions and slightly larger drops. The consistent improvement after fine-tuning demonstrates that the adaptation strategy effectively mitigates domain shifts across tasks.These results indicate that our model possesses strong cross-dataset generalization: even when applied to a different MRI dataset, the model can achieve high classification performance with minimal fine-tuning, validating the transferability and robustness of the learned features.

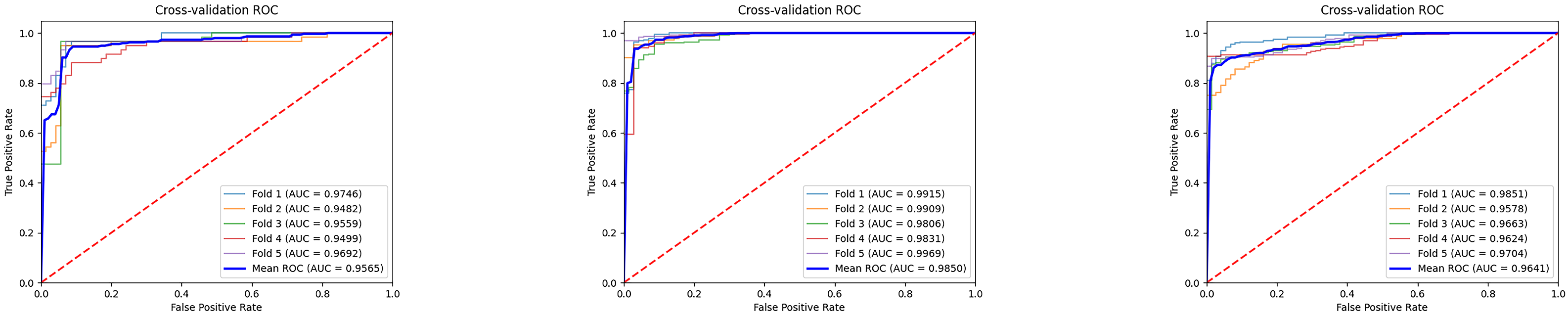

The

Figure 7 illustrates the ROC curves and average results of three binary classification tasks under five-fold cross-validation. It can be observed that the ROC curves of all three tasks are tightly clustered in the upper-left corner, indicating stable and superior classification performance. The average AUC values all exceed 0.95, with the MCI vs. NC task achieving the most prominent result, reaching an average AUC of 0.9850, which demonstrates the high reliability of the model in distinguishing mild cognitive impairment from normal controls. The average AUC values for the AD vs. MCI and AD vs. NC tasks are 0.9565 and 0.9641, respectively, also reflecting strong discriminative capability. Overall, these results indicate that the proposed model exhibits good generalization ability and stability across different classification tasks, providing strong support for the auxiliary diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease at different stages. Furthermore, we conducted extended evaluations of the model’s interpretability, as shown in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9.

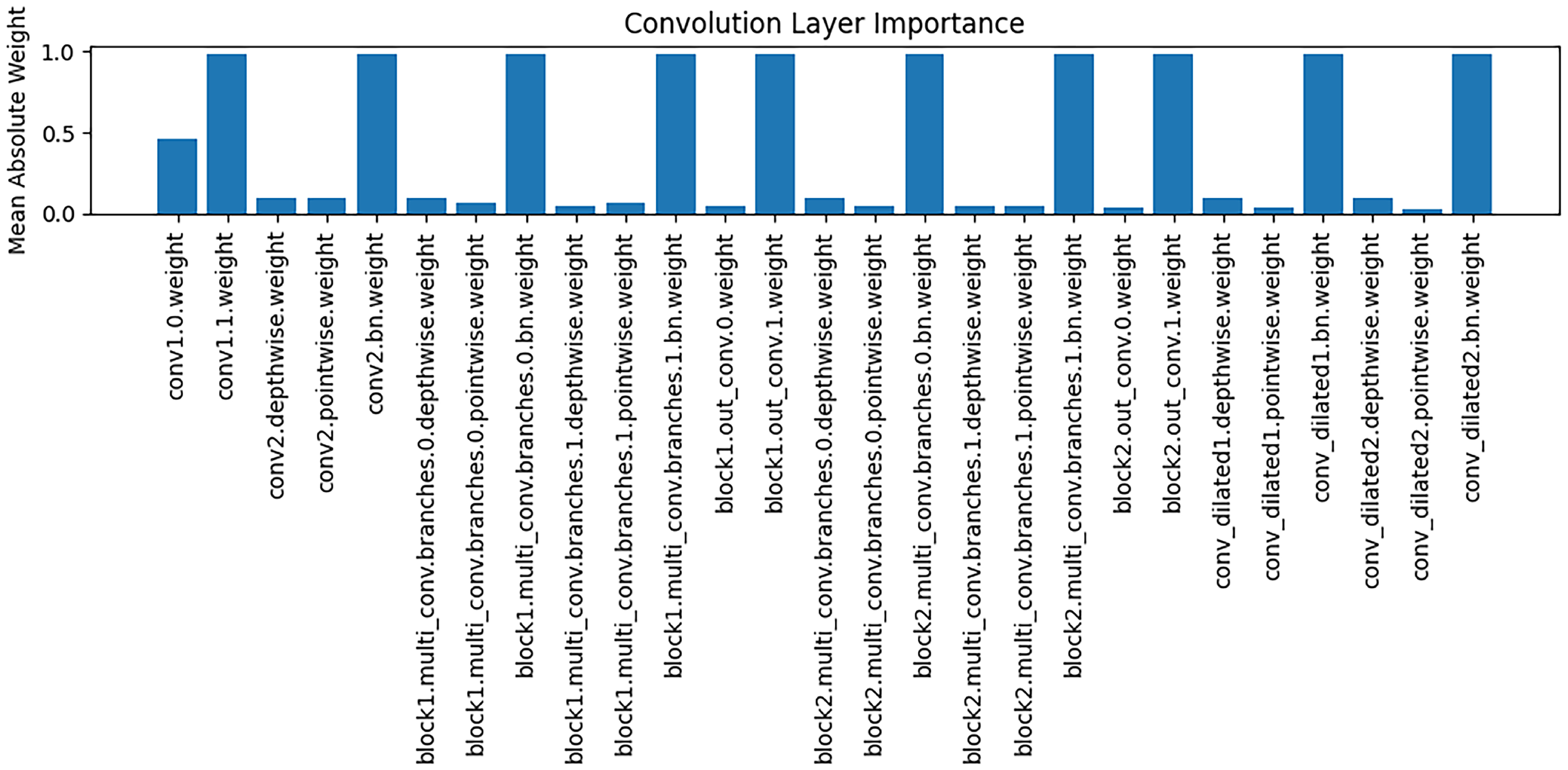

The

Figure 8 presents an analysis of the importance of weights across different convolutional layers, with the vertical axis representing the mean absolute value of the weights. It can be observed that different convolutional layers play distinct roles in feature extraction: some layers (e.g., conv1.0.weight) exhibit relatively high weight magnitudes, indicating that these layers contribute more significantly to the extraction of key features during modeling; whereas other layers have weight magnitudes close to zero, suggesting a limited role in feature representation. These findings support the interpretability of the model, implying that the reliance on feature extraction varies across stages, and that critical convolutional layers play a central role in capturing Alzheimer’s disease–related brain structural features.

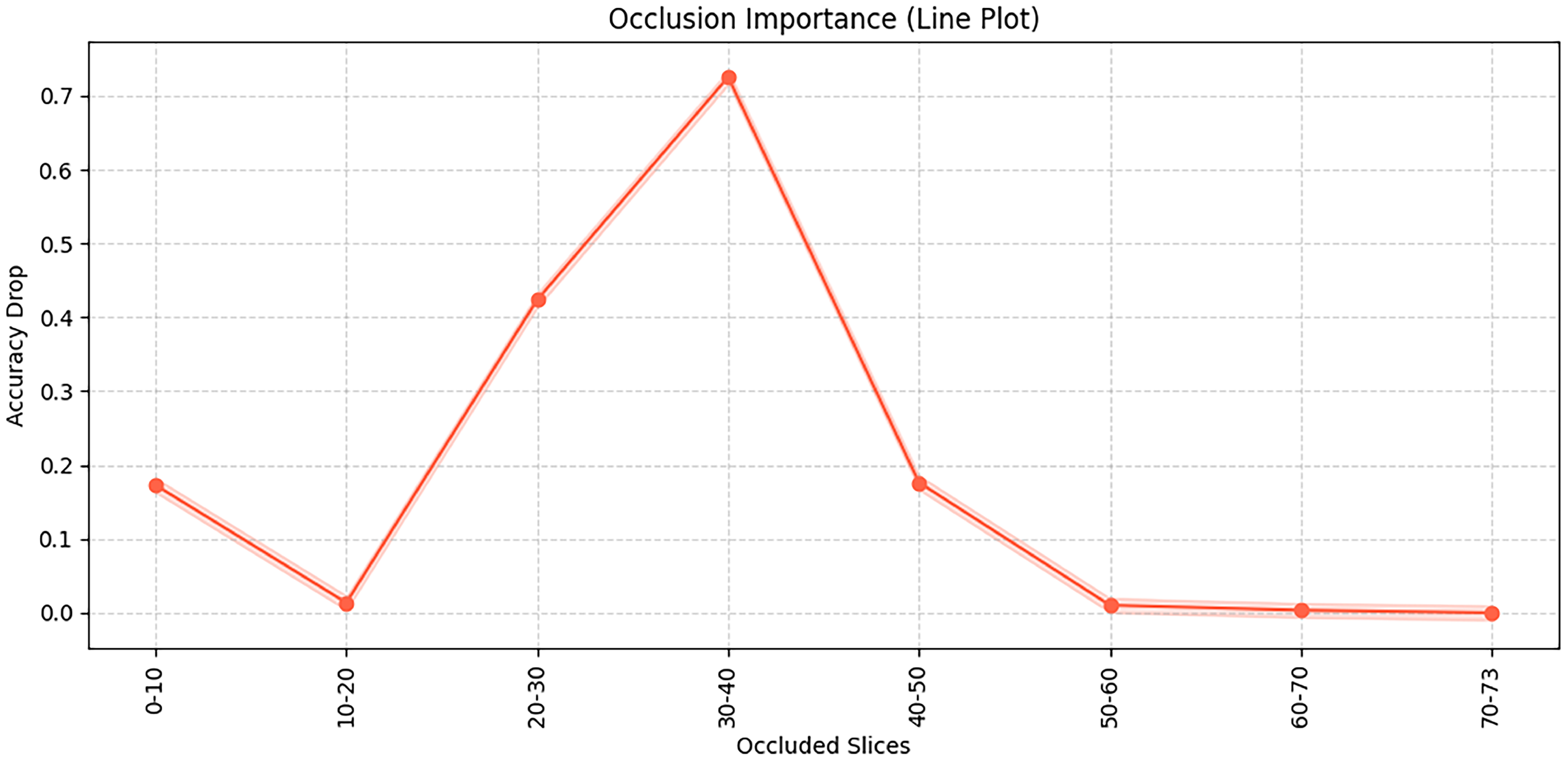

This

Figure 9 illustrates the results of an occlusion test, showing the importance of different brain slices for the model’s classification decisions. Specifically, the occlusion test is conducted by systematically masking consecutive slices of the input 3D MRI volume and observing the resulting changes in classification accuracy, thereby revealing which slices are most critical for the model’s predictions. It can be observed that occluding slices 30–40 leads to the most significant accuracy drop, indicating that this region contains critical discriminative information. Similarly, occlusion of slices 20–30 also has a noticeable impact. In this study, each MRI scan consists of 73 axial slices (from inferior to superior), and this number is kept constant for all subjects after preprocessing. The “slices” refer to 2D cross-sectional images of the brain along the axial plane, corresponding roughly to different anatomical regions from the cerebellum and brainstem (lower slices) to cortical regions (upper slices). In contrast, occluding slices in the ranges of 0–20 and after 50 has relatively little effect on model performance, suggesting that these regions contribute less to the decision-making process. Therefore, the occluded slices between 20–40 mainly correspond to middle cerebral regions such as the hippocampus and temporal lobes, which are known to be closely associated with Alzheimer’s disease pathology.