Multi-Level Attribute-Guided-Based Adaptive Multi-Dilated Convolutional Network for Image Aesthetic Assessment

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We propose a new IAA model, named Multi-level Attribute-Guided-based Adaptive Multi-Dilated Convolutional Network (MAADN), which first implements multi-level guidance from attribute features to the IAA task, simulating the hierarchical mechanism of the human visual system. Meanwhile, this model can achieve a better consistency with subjective aesthetic quality ratings.

- We design an Attention-based Attribute-Guided Aesthetic Module (AGAM), which effectively implements the guidance of attribute features on aesthetic features through the attention mechanism, improving the accuracy and interpretability of the model.

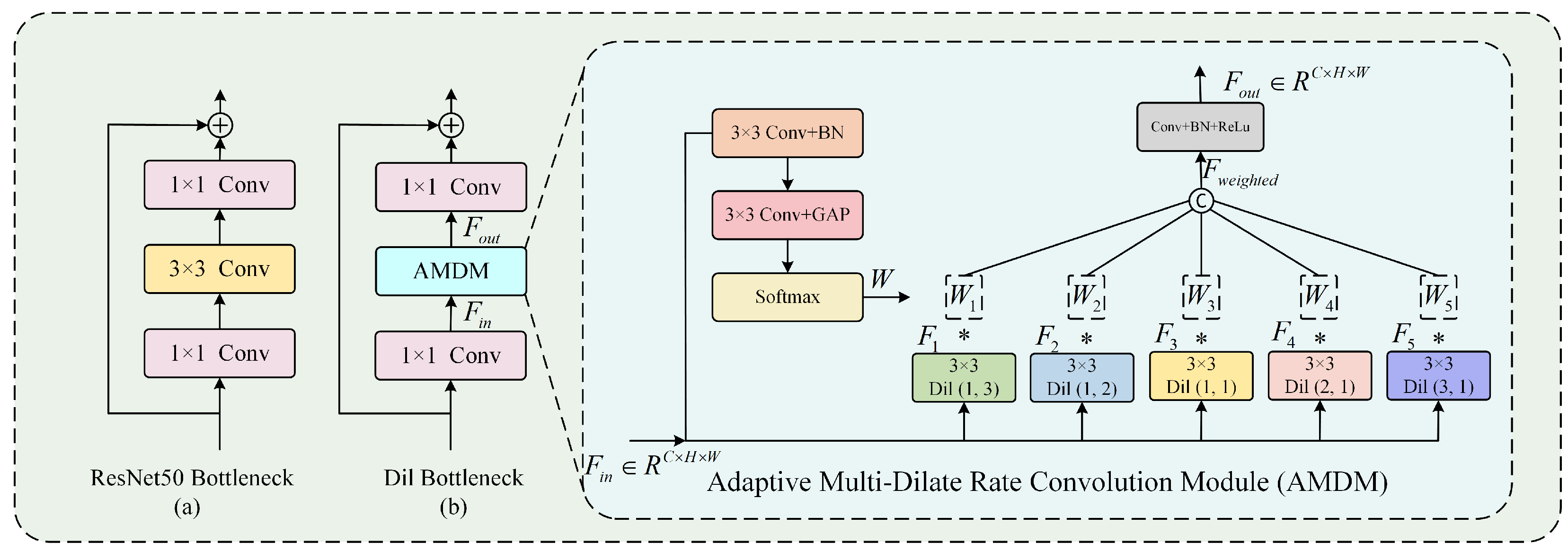

- We design an Adaptive Multi-Dilate Rate Convolution Module (AMDM) that dynamically weights features from parallel dilated convolutions with different dilation rates. This effectively alleviates the negative impact of image preprocessing and the constraint of small-batch training.

2. Related Works

2.1. Hand-Crafted Feature-Based IAA

2.2. Deep Learning-Based IAA

2.2.1. Attribute-Guided Methods

2.2.2. Composition-Preserving Methods

2.2.3. Other Related IAA Methods

3. Proposed Method

3.1. Overall Structure

- : Feature map output from the l-th Res Block in the Attribute Branch

- : Feature map output from the l-th Dil Block in the Aesthetic Branch

- : Feature map output from the l-th AGAM module

- : Nonlinear transformation function of the l-th Res Block

- : Nonlinear transformation function of the l-th Dil Block

- : Nonlinear transformation function of the l-th AGAM

3.2. Attention-Based Attribute-Guided Aesthetic Module (AGAM)

- : Channel attention weights;

- : Spatial attention weights;

- : Feature map obtained by applying a channel attention mechanism to ;

- : Intermediate feature map created by fusing and .

3.3. Adaptive Multi-Dilate Rate Convolution Module (AMDM)

- : Input feature map;

- : Feature map from the i-th dilated convolution;

- : Adaptive weights for feature fusion;

- : Weighted concatenation of all dilated convolution outputs;

- : Final output feature map;

- : Nonlinear transformation of AMDM module;

- K: Number of Dil Bottlenecks in each Dil Block;

- : Transformation of j-th Dil Bottleneck.

4. Experiments

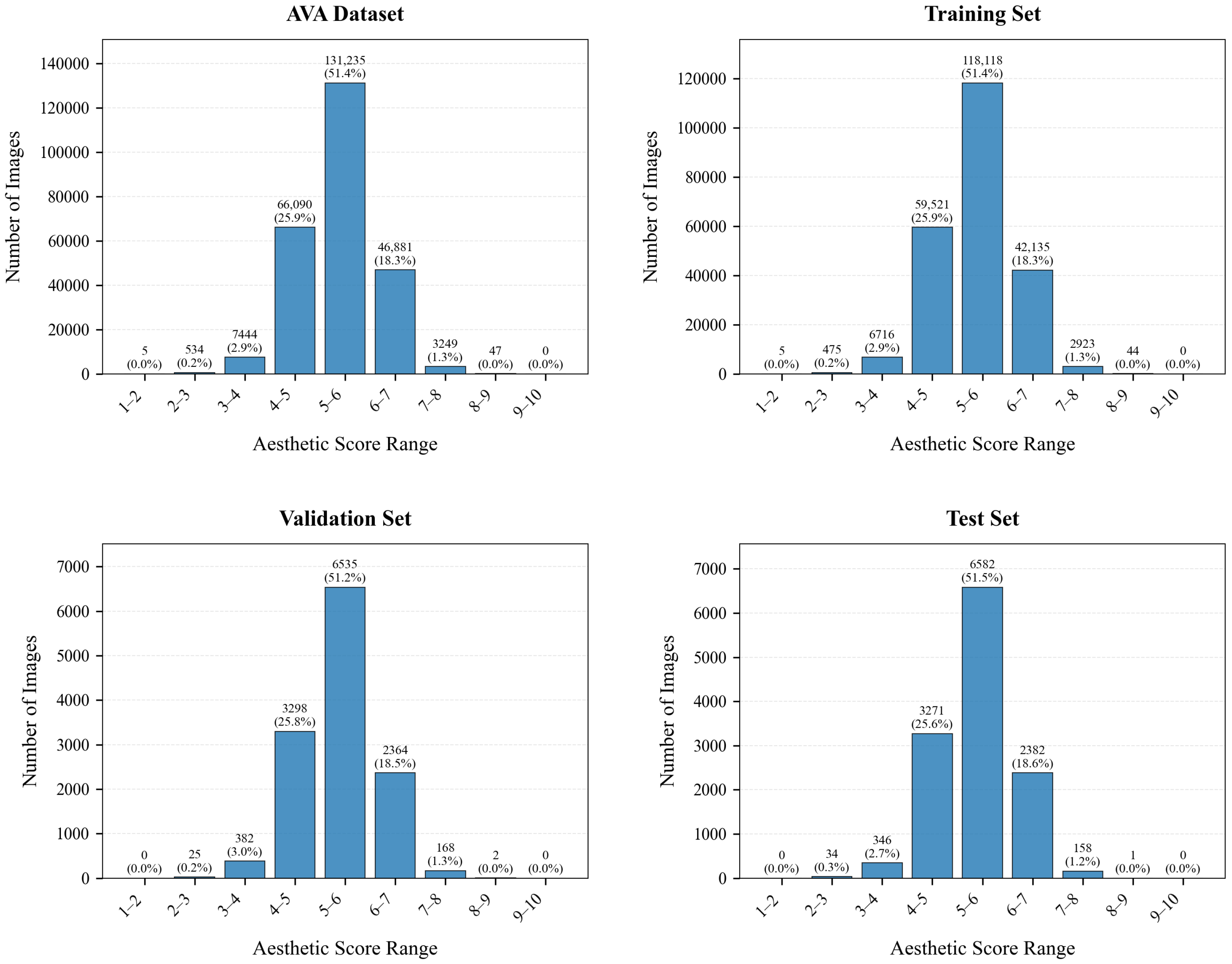

4.1. Databases

4.2. Implementation Details

4.3. Performance Evaluation

| Method | SRCC ↑ | PLCC ↑ | ACC ↑ | EMD ↓ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A-Lamp(VGG16) [47] | - | - | 82.50% | - |

| NIMA(VGG16) [12] | 0.592 | 0.610 | 80.60% | 0.052 |

| NIMA(Inception) [12] | 0.612 | 0.636 | 81.51% | 0.050 |

| GRF-CNN(VGG16) [48] | 0.676 | 0.687 | 80.70% | 0.046 |

| GRF-CNN(Inception) [48] | 0.690 | 0.704 | 81.81% | 0.045 |

| AFDC(ResNet50) [22] | 0.649 | 0.671 | 83.24% | 0.045 |

| MUSIQ(VIT) [46] | 0.726 | 0.738 | 81.50% | - |

| HLA-GCN(ResNet101) [49] | 0.665 | 0.687 | 84.60% | 0.043 |

| TAAN(Swim-T) [50] | - | - | 76.82% | - |

| IAFormer(VIT) [31] | 0.664 | 0.674 | 82.00% | 0.065 |

| HNEF(ResNet50) [51] | 0.679 | 0.694 | 83.90% | 0.040 |

| SPTF-CNN(VIT) [52] | 0.687 | 0.709 | 84.50% | 0.043 |

| ANKE(EfficientNet) [53] | 0.710 | 0.719 | - | 0.044 |

| Zhang(ResNet50) [54] | 0.664 | 0.674 | 82.00% | 0.065 |

| CompoNet(ResNet34) [55] | 0.678 | 0.680 | 83.80% | 0.061 |

| MMANet(MobileNet) [56] | 0.700 | 0.715 | 81.86% | 0.048 |

| CILNet(ResNet18) [57] | 0.693 | 0.702 | 84.20% | 0.059 |

| WMPR-Net(ResNet-50) [58] | 0.703 | 0.713 | 80.20% | 0.045 |

| MAADN (ours) | 0.714 | 0.728 | 81.94% | 0.043 |

| Method | SRCC ↑ | PLCC ↑ | ACC ↑ |

|---|---|---|---|

| RegNet(AlexNet) [40] | 0.678 | - | - |

| PA IAA(DenseNet) [59] | 0.715 | 0.730 | 70.63% |

| NIMA(ResNet50) [12] | 0.708 | 0.711 | 80.10% |

| MLSP(Inception) [60] | 0.719 | 0.717 | 77.20% |

| MUSIQ(VIT) [46] | 0.683 | 0.702 | 75.25% |

| MMANet(MobileNet) [56] | 0.731 | 0.735 | 77.36% |

| WMPR-Net(ResNet-50) [58] | 0.719 | 0.713 | - |

| MAADN (ours) | 0.733 | 0.737 | 77.48% |

| Method | SRCC ↑ | PLCC ↑ | ACC ↑ |

|---|---|---|---|

| PA IAA(DenseNet) [59] | 0.877 | 0.919 | 87.50% |

| NIMA(ResNet50) [12] | 0.891 | 0.913 | 88.60% |

| MLSP(Inception) [60] | 0.832 | 0.897 | 83.70% |

| MUSIQ(VIT) [46] | 0.875 | 0.918 | 88.30% |

| MMANet(MobileNet) [56] | 0.895 | 0.924 | 87.86% |

| MAADN (ours) | 0.898 | 0.925 | 86.57% |

4.4. Ablation Study

4.5. Sensitivity Analysis for Hierarchical Selection

4.6. Statistical Significance Analysis

4.7. Computational Efficiency Analysis

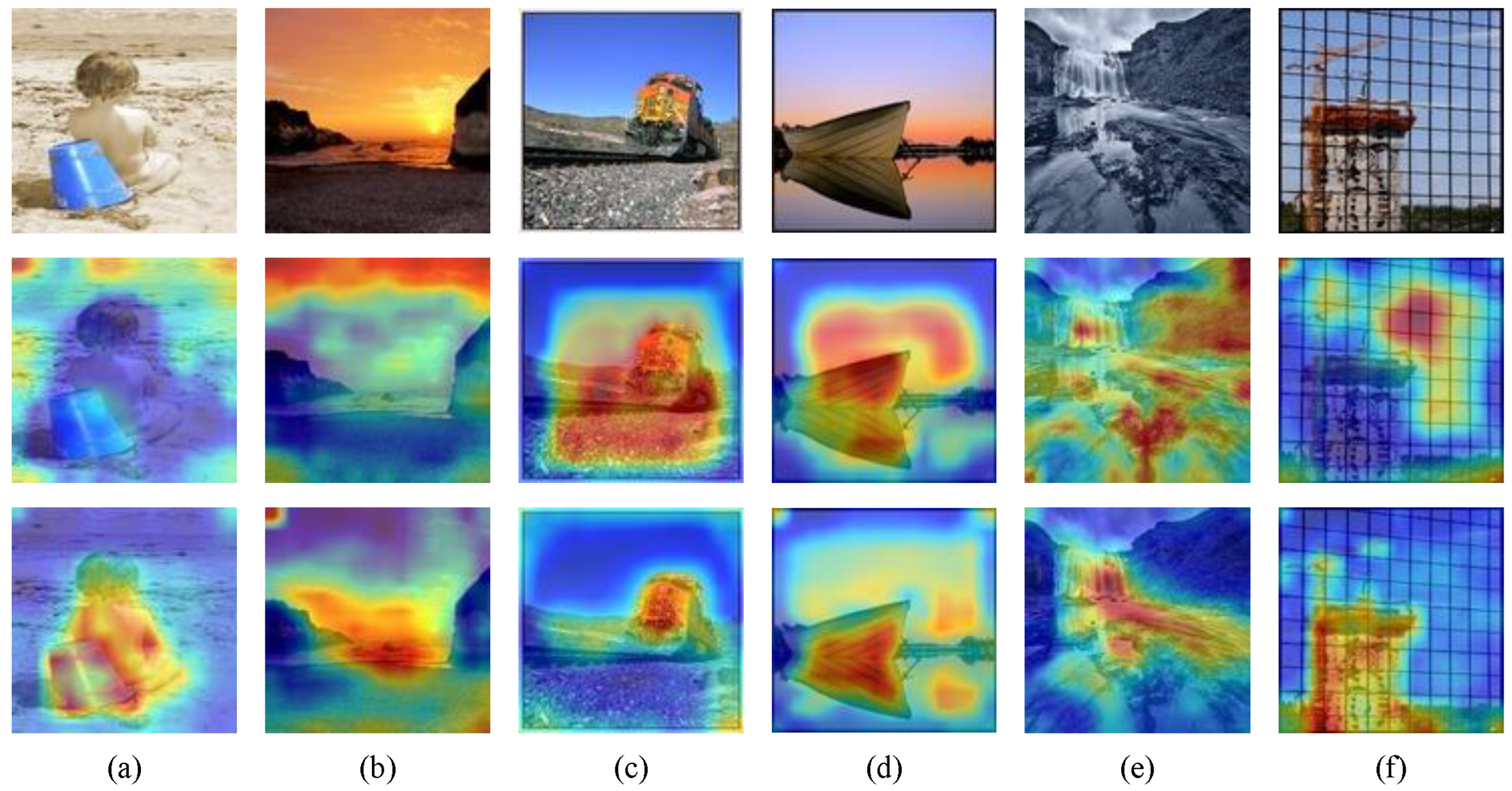

4.8. Visualization Experiment

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lu, P.; Zhang, H.; Peng, X.; Jin, X. Learning the relation between interested objects and aesthetic region for image cropping. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2021, 23, 3618–3630. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Zhang, P.; Wang, C. Harmonious textual layout generation over natural images via deep aesthetics learning. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2022, 24, 3416–3428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Tian, X.; Mei, T. Multigranular event recognition of personal photo albums. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2018, 20, 1837–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, Y.S.; Kankanhalli, M.S. Clicksmart: A context-aware viewpoint recommendation system for mobile photography. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2017, 27, 149–158. [Google Scholar]

- Perronnin, F.; Dance, C. Fisher kernels on visual vocabularies for image categorization. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 17–22 June 2007; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Datta, R.; Joshi, D.; Li, J.; Wang, J. Studying aesthetics in photographic images using a computational approach. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Graz, Austria, 7–13 May 2006; pp. 288–301. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, Y.; Tang, X.; Jing, F. The design of high-level features for photo quality assessment. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Graz, Austria, 7–13 May 2006; Volume 1, pp. 419–426. [Google Scholar]

- Le, Q.T.; Ladret, P.; Nguyen, H.T.; Caplier, A. Image aesthetic assessment based on image classification and region segmentation. J. Imaging 2020, 7, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, Y. Exploring metrics to establish an optimal model for image aesthetic assessment and analysis. J. Imaging 2022, 8, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y. Building cnn-based models for image aesthetic score prediction using an ensemble. J. Imaging 2023, 9, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Lin, Z.; Jin, H.; Yang, J.; Wang, J.Z. RAPID: Rating pictorial aesthetics using deep learning. In Proceedings of the ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Orlando, FL, USA, 3–7 November 2014; pp. 457–466. [Google Scholar]

- Talebi, H.; Milanfar, P. NIMA: Neural image assessment. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2018, 27, 3998–4011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ligaya, K.; Yi, S.; Wahle, I.A.; Tanwisuth, K.; Doherty, J.P. Aesthetic preference for art can be predicted from a mixture of low- and high-level visual features. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021, 5, 743–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhao, M.; Wang, L.; Huang, J.; Cai, C.; Xu, X. A multi-scene deep learning model for image aesthetic evaluation. Signal Process. Image Commun. 2016, 47, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Huang, Y.; Wu, J.; Yang, Y.; Li, Y.; Guo, Y.; Shi, G. Theme-aware visual attribute reasoning for image aesthetics assessment. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2023, 33, 4798–4811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, Y.; He, R.; Huang, K. Deep aesthetic quality assessment with semantic information. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2017, 26, 1482–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Wu, L.; Zhao, G.; Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Ge, S.; Zou, D.; Zhou, B.; Zhou, X. Aesthetic attributes assessment of images. In Proceedings of the 27th ACM international Conference on Multimedia, Nice, France, 21–25 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, B.; Wang, S.; Jiang, Q. Image aesthetic assessment assisted by attributes through adversarial learnings. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Honolulu, HI, USA, 27 January–1 February 2019; Volume 33, pp. 679–686. [Google Scholar]

- Leder, H.; Belke, B.; Oeberst, A.; Augustin, D. A model of aesthetic appreciation and aesthetic judgments. Br. J. Med. Psychol. 2004, 95, 489–508. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Shao, F.; Chai, X.; Mu, B.; Jiang, Q. Art Comes From Life: Artistic Image Aesthetics Assessment via Attribute Knowledge Amalgamation. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2024, 35, 4172–4183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, L.; Jin, H.; Liu, F. Composition-preserving deep photo aesthetics assessment. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 497–506. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, N.; Lei, P.; Xu, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Fan, J. Adaptive fractional dilated convolution network for image aesthetics assessment. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 14114–14123. [Google Scholar]

- Burges, C.J.C. A tutorial on support vector machines for pattern recognition. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 1998, 2, 121–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rish, I. An empirical study of the naive Bayes classifier. In Proceedings of the IJCAI 2001 Workshop on Empirical Methods in Artificial Intelligence, Seattle, WA, USA, 4–10 August 2001; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama, M.; Okabe, T.; Sato, I.; Sato, Y. Aesthetic quality classification of photographs based on color harmony. In Proceedings of the CVPR 2011, Colorado Springs, CO, USA, 20–25 June 2011; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Su, H.H.; Chen, T.W.; Kao, C.C.; Hsu, W.H.; Chien, S.Y. Scenic photo quality assessment with bag of aesthetics-preserving features. In Proceedings of the 19th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Scottsdale, AZ, USA, 28 November–1 December 2011; pp. 1213–1216. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, D.G. Distinctive image features from scale-invariant keypoints. International Journal of Computer Vision 2004, 60, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Y.; Li, Q.; Liu, L.; Xu, G. Privileged multi-task learning for attribute-aware aesthetic assessment. Pattern Recognit. 2022, 132, 108921. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, X.; Lin, Z.; Shen, X.; Mech, R.; Wang, J.Z. Deep multi-patch aggregation network for image style, aesthetics, and quality estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; pp. 990–998. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, X.; Lou, H.; Huang, H.; Li, X.; Li, X.; Cui, S.; Li, X. Pseudo-labeling and meta reweighting learning for image aesthetic quality assessment. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 25226–25235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Jin, Y. Iaformer: A transformer network for image aesthetic evaluation and cropping. In Proceedings of the 2022 6th Asian Conference on Artificial Intelligence Technology (ACAIT), Changzhou, China, 9–11 December 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Zhu, T.; Chen, P.; Yang, Y.; Li, Y.; Lin, W. Image aesthetics assessment with attribute-assisted multimodal memory network. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2023, 33, 7413–7424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Su, C.; Hu, X.; Chen, M.; Sun, Y.; Dong, Z.; Liu, T.; Luo, J. AMFMER: A multimodal full transformer for unifying aesthetic assessment tasks. Signal Process. Image Commun. 2025, 138, 117320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Qiao, Z.; Chen, R.; Li, J.; Wang, W.; Wang, X.; Rao, W.; Chen, S.; Liu, A.A. Aesthetic Perception Prompting for Interpretable Image Aesthetics Assessment with MLLMs. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2025—2025 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Hyderabad, India, 6–11 April 2025; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Xiao, L.; Wu, X.; Ma, T.; Zhao, J.; He, L. Artistry in pixels: Fvs-a framework for evaluating visual elegance and sentiment resonance in generated images. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME), Niagara Falls, ON, Canada, 15–19 July 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, Y.; Xiao, L.; Wu, X.; Yang, J.; He, L. Imaginique Expressions: Tailoring Personalized Short-Text-to-Image Generation Through Aesthetic Assessment and Human Insights. Symmetry 2024, 16, 1608. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, L.; Wu, X.; Xu, J.; Li, W.; Jin, C.; He, L. Atlantis: Aesthetic-oriented multiple granularities fusion network for joint multimodal aspect-based sentiment analysis. Inf. Fusion 2024, 106, 102304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maerten, A.S.; Chen, L.W.; De Winter, S.; Bossens, C.; Wagemans, J. LAPIS: A novel dataset for personalized image aesthetic assessment. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Conference, Nashville, TN, USA, 11–15 June 2025; pp. 6302–6311. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, S.; Shen, X.; Lin, Z.; Mech, R.; Fowlkes, C. Photo aesthetics ranking network with attributes and content adaptation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; pp. 662–679. [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe, S.; Fize, D.; Marlot, C. Speed of processing in the human visual system. Nature 1996, 381, 520–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, A.; Torralba, A. Modeling the shape of the scene: A holistic representation of the spatial envelope. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2001, 42, 145–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 7132–7141. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, N.; Marchesotti, L.; Perronnin, F. AVA: A large-scale database for aesthetic visual analysis. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Providence, RI, USA, 16–21 June 2012; pp. 2408–2415. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Xu, L.; Li, L.; Qie, N.; Li, Y.; Zhang, P.; Guo, Y. Personalized image aesthetics assessment with rich attributes. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 19861–19869. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, J.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Milanfar, P.; Yang, F. Musiq: Multi-scale image quality transformer. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, BC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 5148–5157. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, S.; Liu, J.; Wen Chen, C. A-lamp: Adaptive layout-aware multi-patch deep convolutional neural network for photo aesthetic assessment. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 4535–4544. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Gao, X.; Lu, W.; He, L. A gated peripheral-foveal convolutional neural network for unified image aesthetic prediction. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2019, 21, 2815–2826. [Google Scholar]

- She, D.; Lai, Y.K.; Yi, G.; Xu, K. Hierarchical layout-aware graph convolutional network for unified aesthetics assessment. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 8475–8484. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, G. Theme-Aware Semi-Supervised Image Aesthetic Quality Assessment. Mathematics 2022, 10, 2609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, G.; Xiao, S.; Yang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Wen, J.; Lu, W.; Gao, X. Image aesthetics assessment based on hypernetwork of emotion fusion. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2023, 26, 3640–3650. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, K.; Qin, F.; Guo, J.; Yang, S. Image aesthetics assessment using composite features from transformer and CNN. Multimed. Syst. 2023, 29, 2483–2494. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Zhi, T.; Shi, G.; Yang, Y.; Xu, L.; Li, Y.; Guo, Y. Anchor-based knowledge embedding for image aesthetics assessment. Neurocomputing 2023, 539, 126197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zhu, D.; Min, X.; Gao, Z.; Zhai, G. Synergetic assessment of quality and aesthetic: Approach and comprehensive benchmark dataset. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2023, 34, 2536–2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xu, J.; Zou, R. Research on Image Aesthetic Assessment based on Graph Convolutional Network. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME), Niagra Falls, ON, Canada, 15–19 July 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Liang, H.; Xie, M.; He, X. Multi-scale and multi-patch aggregation network based on dual-column vision fusion for image aesthetics assessment. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME), Niagra Falls, ON, Canada, 15–19 July 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, W.; Ke, Y.; Wang, K.; Yang, S.; Qin, F. Multi-theme image aesthetic assessment based on incremental learning. Signal Image Video Process. 2025, 19, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Guo, J.; Ke, Y.; Wang, K.; Yang, S.; Chen, L. Image aesthetic assessment with weighted multi-region aggregation based on information theory. Pattern Anal. Appl. 2025, 28, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhu, H.; Zhao, S.; Ding, G.; Lin, W. Personality-assisted multi-task learning for generic and personalized image aesthetics assessment. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2020, 29, 3898–3910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosu, V.; Goldlucke, B.; Saupe, D. Effective aesthetics prediction with multi-level spatially pooled features. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 9375–9383. [Google Scholar]

- Wilcoxon, F. Individual comparisons by ranking methods. Biom. Bull. 1992, 1, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosovitskiy, A. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar]

| Method | SRCC ↑ | PLCC ↑ | ACC ↑ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 0.671 | 0.683 | 79.80% |

| Baseline + AMDM | 0.685 | 0.694 | 80.43% |

| Single-Level Guide | 0.689 | 0.701 | 80.76% |

| SG + AGAM | 0.692 | 0.703 | 80.85% |

| SG + AMDM | 0.701 | 0.710 | 81.39% |

| SG + AGAM + AMDM | 0.704 | 0.716 | 81.64% |

| Multi-Level Guide | 0.696 | 0.706 | 81.05% |

| MG + AGAM | 0.701 | 0.710 | 81.39% |

| MG + AMDM | 0.709 | 0.719 | 81.78% |

| MAADN (ours) | 0.714 | 0.728 | 81.94% |

| Guidance Hierarchy | SRCC ↑ | PLCC ↑ | ACC ↑ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1 | 0.681 | 0.703 | 80.19% |

| Level 2 | 0.688 | 0.698 | 80.61% |

| Level 3 | 0.689 | 0.700 | 80.68% |

| Level 4 | 0.692 | 0.703 | 80.85% |

| Levels 3–4 | 0.697 | 0.706 | 80.99% |

| Levels 2–4 | 0.698 | 0.708 | 81.13% |

| Levels 1–4 (ours) | 0.701 | 0.710 | 81.39% |

| Metric | Baseline | Proposed (MAADN) | Wilcoxon p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| SRCC | * | ||

| PLCC | * | ||

| ACC (%) | * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, S.; Xie, M.; Xiang, W. Multi-Level Attribute-Guided-Based Adaptive Multi-Dilated Convolutional Network for Image Aesthetic Assessment. J. Imaging 2025, 11, 420. https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging11120420

Li S, Xie M, Xiang W. Multi-Level Attribute-Guided-Based Adaptive Multi-Dilated Convolutional Network for Image Aesthetic Assessment. Journal of Imaging. 2025; 11(12):420. https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging11120420

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Sumei, Mingxuan Xie, and Wei Xiang. 2025. "Multi-Level Attribute-Guided-Based Adaptive Multi-Dilated Convolutional Network for Image Aesthetic Assessment" Journal of Imaging 11, no. 12: 420. https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging11120420

APA StyleLi, S., Xie, M., & Xiang, W. (2025). Multi-Level Attribute-Guided-Based Adaptive Multi-Dilated Convolutional Network for Image Aesthetic Assessment. Journal of Imaging, 11(12), 420. https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging11120420