Abstract

Municipal Solid Waste (MSW) management is an essential service for an urban population to maintain sanitation. Managing MSW is complex as the treatment/recovery options depend not only on the volume of waste, but also on the socioeconomic conditions of the population. This paper focusses on MSW management in the Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) countries. Dominance of uncontrolled disposal options of MSW in the region, such as open dumps, has an adverse influence on health and sanitation. Interest in source separation practices and recycling is low in the LAC region. Furthermore, economic matters such as poor financial planning and ineffective billing systems also hinder service sustainability. Rapid urbanization is another characteristic feature in the region. The large urban centres that accommodate over 80% of the region’s population pose their own challenges to MSW management. However, the same large volume of MSW generated can become a steady supply of resources, if recovery options are prioritized. Governance is one aspect that binds many activities and stakeholders involved in MSW management. This manuscript describes how we may look at MSW management in LAC from the governance perspective. The issues, as well as the best potential solutions, are both described within three categories of governance: bureaucratic, market, and network. The governance perspective can assist by explaining which stakeholders are involved and who should be responsible for what. Financial issues are the major setbacks observed in the bureaucratic governance institutions that can be reversed with better billing strategies. MSW is still not seen by the private sector as a place to make investments, perhaps due to the negative social attitude associated with waste. The market governance aspects may help increase the efficiency and profitability of the MSW market. Private sector initiatives such as cost-effective microenterprises should be encouraged and the projects that fit under the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) defined in the Kyoto Protocol should be incentivized to attract technology and capital. Lastly, network governance is at the centre of attention due to its flexibility in supporting/absorbing public-private partnerships, especially the participation of the informal sector that is important to the LAC region. Many individual waste pickers are providing their services to the LAC region by taking part in collecting and recycling under very unfavourable working conditions.

1. Introduction

Municipal Solid Waste (MSW) management has presented many different challenges to mankind throughout history. The elements of global change, comprised of population growth, urbanization, and climate change, have also contributed to making MSW management a complex issue. People used to look at waste as a nuisance when resources were abundant; fortunately, that thinking is slowly changing now mainly due to the depletion of natural resources. Clearly, there is now a positive trend of seeing waste as a resource. The “resource” perspective depends heavily not only on the volume, but also on the composition, which is closely tied to the socioeconomic status of the population. For example, MSW from developing countries and regions usually has a higher percentage of biodegradable (organic) material compared to the developed countries [1,2,3]. Another recent example is how the composition of waste changes in the two largest populations in the world —India and China—just because of the growing middle class in the two countries. MSW management strategies should also take these trends into account for the best possible results [4].

MSW management in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) is no exception to this phenomenon. LAC countries have fast-growing cities with increasing rates of waste generation. But the management practices have not evolved to catch up with these realities and cope with the increased generation. Like any other region in the world, LAC also has some characteristic features unique to the region. One such uniqueness is that it has the highest city-dwelling population. The urban population in LAC exceeded 80% years ago [5]. Another interesting observation is the high organic content in the waste which LAC shares with many other developing regions [1]. However, the highest recorded food waste in the cereal industry is one of the major factors truly unique to the region [6]. Even though high population centres usually sound like a challenge in terms of waste management responsibilities, there is also a bright side in having a guaranteed supply of waste stream if the management practices can be designed to look at them as opportunities.

However, one of the major issues preventing us from making progress is the deficiencies in the governance aspects. The governance aspects usually explain how society participates in and accomplishes complex tasks to achieve a common goal such as the MSW management process, which includes many stakeholders because it is closely attached to day-to-day living of the population. Strengthening the governance aspects of MSW management in LAC countries is crucial because; first, their urban populations are extremely high and still growing; and second, improperly managed MSW is now causing environmental and health problems in the region [7,8,9,10,11]. Therefore, looking at MSW management from the perspective of governance would transparently give some hints to solve problems as to who is involved or who is responsible.

Within this background, the aim of this manuscript is to look at the issues/challenges and opportunities that MSW management has presented in LAC. The fact that we want to emphasize here is that some solutions already exist in the region; a solution that prospered in one country may very well inspire others in the same region. Even though new technological innovations and legislation overhauls can also enhance the efforts, the scope of the study covered in this manuscript is only limited to looking at potential solutions with the governance perspective. To accomplish this objective, we will first discuss the status, issues, and trends of MSW management in LAC countries and explain how these factors are (or should be) related to governance. To accomplish this goal, we also briefly discuss different types of governance structures and how they may be currently practised in LAC. We present some of the main challenges unique to the region and then finally discuss how the same challenges might be translated into opportunities by considering some credible examples from the same region.

2. MSW Management in LAC: Status, Issues, and Trends

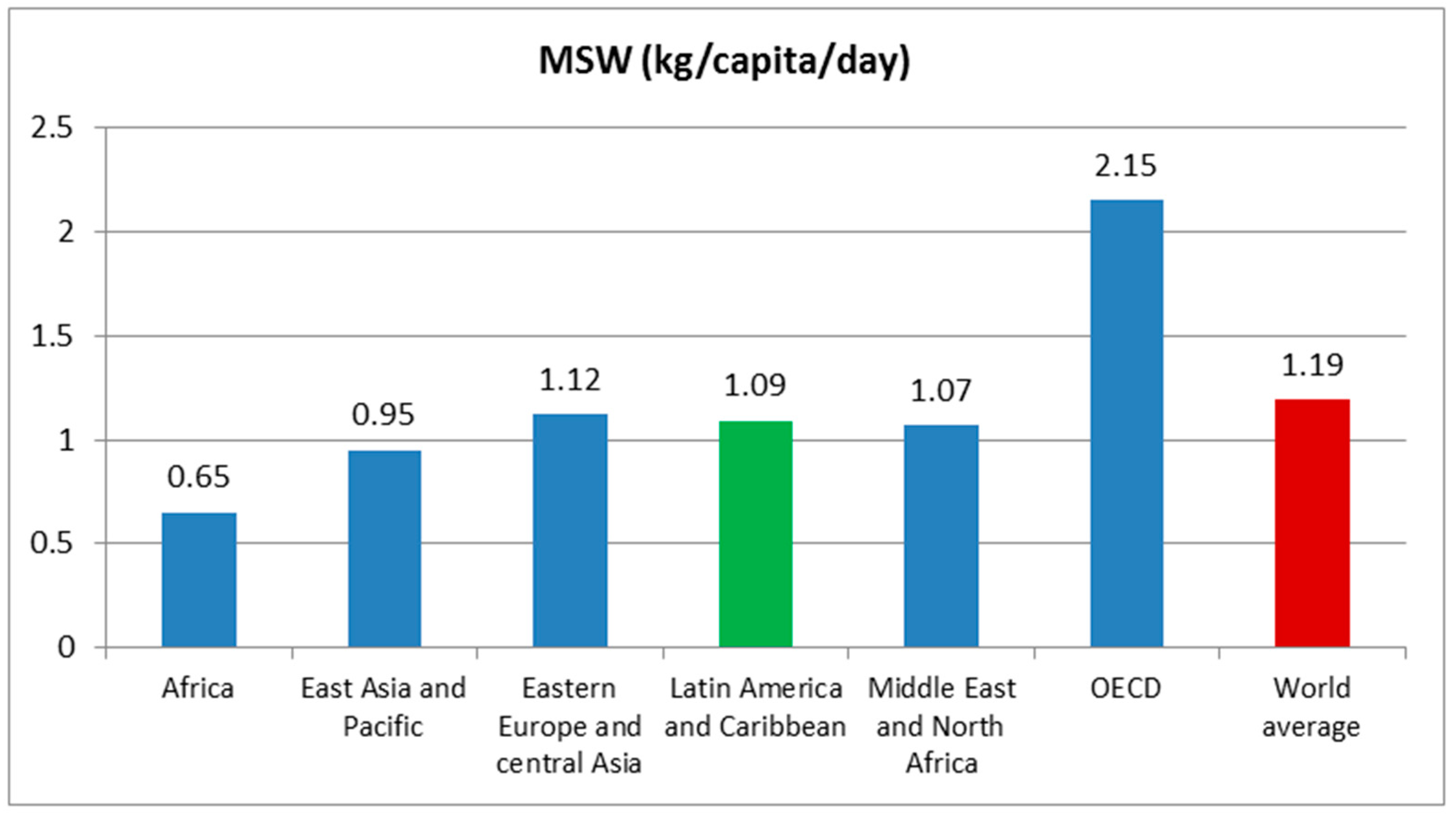

LAC is a region that is home to well over 600 million people [12]. MSW management statistics in LAC countries have some noticeable differences compared to other regions in the world. The generation of MSW in LAC is 1.09 kg/capita/day [1], which keeps LAC on par with the Eastern Europe and MENA region (Figure 1). This rate is much higher than that for Africa, but much lower compared to the members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

Figure 1.

MSW generation (kg/capita/day) by various regions in the world [1].

Waste in developing countries often has a relatively high fraction of organics compared to waste in developed countries [1]. As evident in Table 1, this is also the case for LAC. In the case of LAC, one major reason for this is the high food loss that occurs during the food production process. The usual trend is that the per capita food loss is high among developed countries due to lifestyle and the same is low in developing countries and regions due to socioeconomic reasons. However, there is a clear exception for this trend when it comes to the LAC region. Among all developing regions, LAC has the highest per capita food loss in the world [13]. Major food losses occur in agricultural processing (cereal, fruits, and vegetables) and in the seafood industry. Losses mostly occur during the early and middle stages of the supply chain. In addition, a large volume of agricultural waste (such as husks and leaves) also contributes to the organic fraction in the waste.

Table 1.

Composition (%) of Organic Waste in LAC compared to other regions in the world [1].

2.1. MSW Collection and Disposal

Waste collection coverage in LAC countries is at a relatively high level. Compared to the global average of 73.6%, waste collection (as a percentage of the population) in LAC countries has a high level of coverage of 89.9% [14], with a few countries in the region even reaching the universal coverage of 100% [15]. When the distance from an area of generation to treatment is long, it is recommended to implement transfer stations, which is still not a standard practice in LAC. Only a few large cities in LAC such as Rio de Janeiro, Mexico City, Caracas, and Buenos Aires use transfer stations to cover a little over 50% of the collection [16].

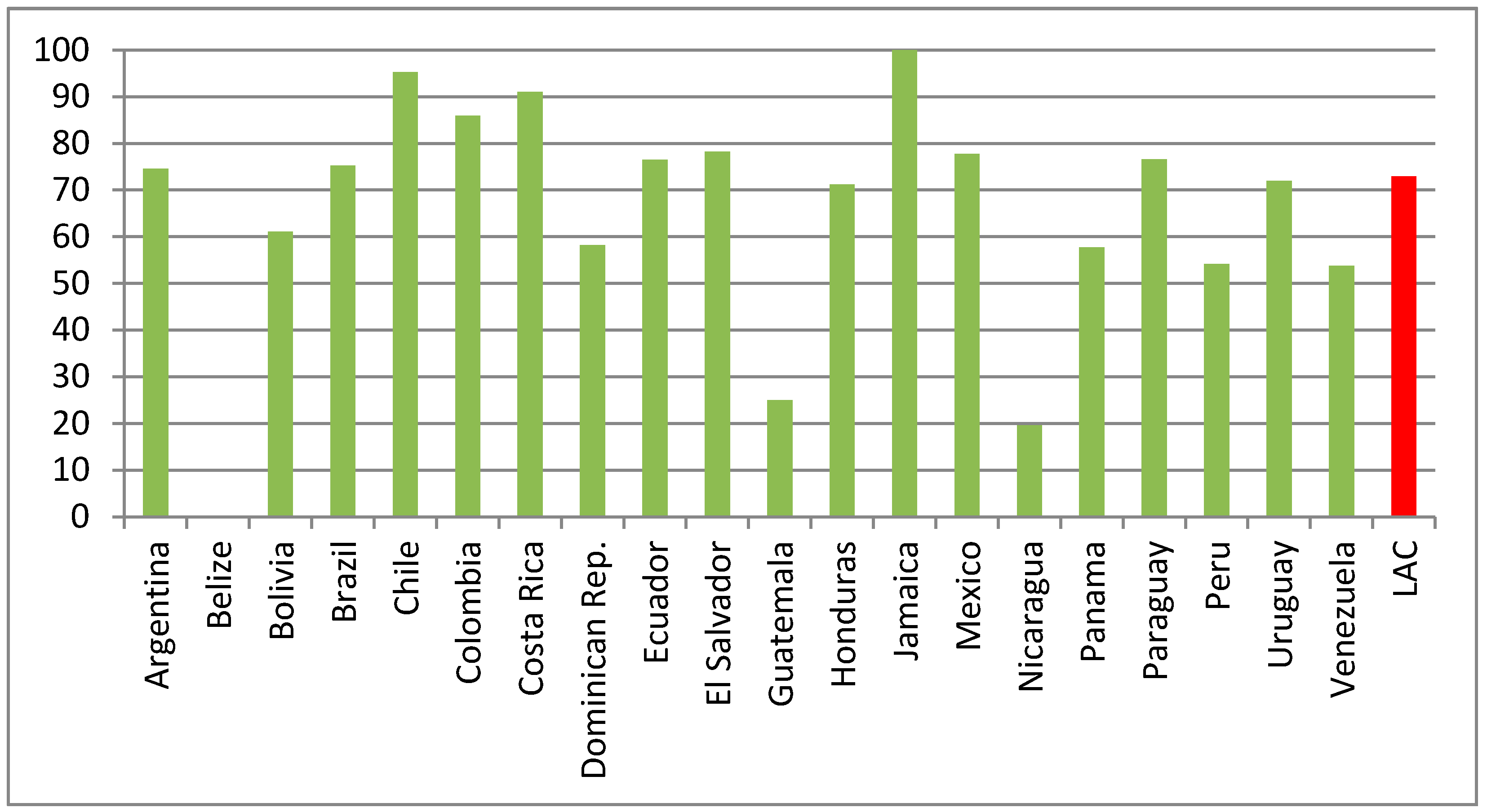

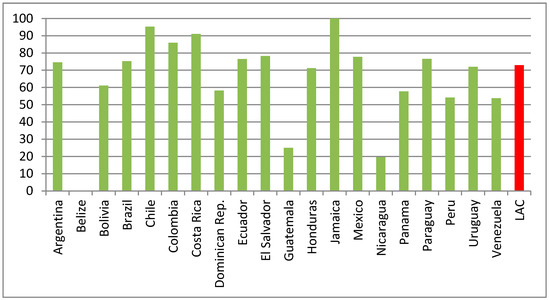

The predominant means of waste disposal in LAC is open dumps, which are highly connected to health and environmental issues [17,18]. Figure 2 provides a snapshot of controlled MSW disposal methods (landfills and controlled dumps) in LAC as a percentage of population covered. No controlled methods are used in Belize; instead, an estimated 85.2% of the population use uncontrolled open-air dumps. The same is true for Guatemala and Nicaragua with 69.8% and 59.3%, respectively [19]. Open-air burning of MSW and its disposal in bodies of water are also noticeable issues in the region and especially in Bolivia, Belize, Nicaragua, Honduras, and Panama [19].

Figure 2.

Controlled MSW disposal methods (landfills and controlled dumps) in LAC as a percentage of population covered [19].

Although the number of properly designed sanitary landfills has significantly increased in the region over the last decade, many of these landfills face significant operational and environmental issues. As covered by the international media in 2011, in Mexico City, Mexico, a waste crisis occurred when the authorities closed the Bordo Poniente landfill, which used to be one of the largest landfills in the world, without providing proper alternatives and highlighting the lack of comprehensive policy [20]. In Colombia, a considerable number of technological failures in landfills caused dangerous situations and deaths between 1977 and 2005 [21].

2.2. Lack of Recycling and Other Technologies

Many LAC countries have not yet overcome the traditional unsorted collection practices. The formal segregation for recycling is currently not practised on a large scale in the region. Only very few countries have sorting plants and employ recycling as a common practice in their MSW management system. Formal means of recycling are still limited to about 2% among all MSW management methods in the region [14,15]. As a result, lots of recyclables end up in landfills and dumps, creating a space for the informal sector to step into the business of service chain provisioning in recycling. Currently, recycling is mostly relying on the informal sector which often does not contribute to any official data on recycling rates [14]. The United Nations’ statistics estimate the total rate of recycling to be about 4%, which is still much lower than other regions in the world; for example, 17% being the same figure for Asia [22].

Many LAC countries are also missing the other types of recovery opportunities. On average, over 50% of the MSW produced in the region is organic (Table 1). High organic content means that there is room for recovery, for example, by making compost or biogas production. However, as waste separation is not a common tradition of the region, they miss the potential for revenue generation from such recovery activities. Waste-to-Energy, which refers to obtaining energy from waste resources, is also not widely implemented in the region. Some major cities such as Sao Paulo, Brazil have shown interest in such technologies; however, no projects have been initiated except for some cases in Bermuda and Martinique [14].

2.3. Deficit in Financial Capacity

A lack of capacity, especially in finances and human resources, has a negative impact on MSW management [23]. The expansion of urban areas in the region is often unplanned and unstructured, creating logistical concerns for both the provisioning of MSW management service and viable waste collection. Central governments usually manage waste issues at the national level. In almost every country in LAC, the allocated budget for MSW management is being managed nationally. But as seen in all other regions in the world, as in LAC too, the municipalities often oversee the service coverage. However, the coordination of financial plans between the central government and the municipalities is usually poor.

Another issue in the public system is its inability to collect revenue for the services it renders. This is mainly due to the lack of a proper structure for collecting fees for the services, thereby exerting a negative impact on their ability to survive financially. Espinoza et al. [19] reported that only 65% of the LAC municipalities bill for their services. As per Grau et al. [14], the real cost recovery is 51.6%. The preferred form of billing for sanitary services in the LAC region is to include it in the property tax dues, which represents 52.1% of the total billing cases [14]. This is not an effective method because the property registration authority seldom updates their records. Direct billing (20.2%), and adding to the electricity bill (15.3%) or water and sanitation bill (12.4%) are also practised [14]. The problems within this system make the recovery of costs difficult to achieve and therefore, other municipal funds are also used to pay for MSW services.

When the revenue is not enough to self-sustain daily operations, it also hinders the planning for capital investments. The municipalities are not able to purchase proper tools/equipment to provide a better-quality service for the collection and treatment of MSW. A lack of infrastructure and equipment also results in poor or insufficient waste treatment technology, as well as safety practices. Simultaneously, they cannot hire sufficient human resources or train the hired ones, creating a human resource deficit. Additionally, municipalities also lack the capability to enforce their own regulations related to MSW management.

2.4. Urbanization Trends and Their Impact

The LAC region has the highest rate of urban growth in the world [15] and is already home to a couple of megacities (population over 10 million) such as Mexico City, Sao Paulo, Buenos Aires, and Rio de Janeiro. Lima and Bogota are also assumed to have surpassed 10 million. This urbanization trend is creating growing concentrations of people, commerce, and industry. Waste proliferation is also constantly evolving in reaction to the population growth, economic growth, and industrialization of each country in the region. Table 2 presents the growth of the urban population of 26 countries in LAC since 1960. It is interesting to note that only six countries out of 26 (Argentina, Bahamas, Chile, Mexico, Uruguay, and Venezuela) had over 50% urban population back in 1960. By 2016, except for four small island nations (Barbados, Grenada, St. Lucia, and Trinidad and Tobago), in all other countries, the urban population had grown well over 50%. As evident in Table 2, the average urban population for the region increased from 49% in 1960 to 80% in 2016. In terms of number of people, this change represents an increase of almost 400 million within half of a century.

Table 2.

Urbanization Statistics for the LAC countries [1,5].

In the LAC countries, there is also a high concentration of population living in urban slums. According to UN-Habitat [15], one out of four inhabitants lives in these informal settlements in LAC. These areas are usually not served by the MSW collection services due to poor accessibility. Installing MSW transfer stations close to such settlements is also not feasible due to the lack of affordable land. Inability to provide sanitary services to part of the population also provides grounds for other social concerns including environmental justice issues.

3. Governance Perspective of MSW Management

It is somewhat clear from the previous discussion that there are major issues related to the financial wellbeing of waste management in LAC. However, simply pumping more money to fill the gap is perhaps not the best solution. The solutions should rather be sustainable and long-lasting, and address the grievances of all actors (or stakeholder groups) involved. However, it is also not easy to identify the roles played by all stakeholders as there are many involved in the MSW management process, from individuals to organizations to authorities. This is perhaps where the concept of governance can lend a helping hand. The perspective of governance should be able to help with transparently showing which stakeholders are involved, who is responsible, and giving hints to solve the problems.

MSW management is a good indicator for measuring how well a governing structure works within an urban society. When MSW management is working without issues, it is likely that the urban society in question is able to deal with the management structures, contracting procedures, labour practices, accounting, cost recovery, corruption, poverty, and equity reasonably well [24]. By the same token, if MSW management faces issues, governance is one of the first things that needs to be checked/fixed. Based on the information presented in the previous section, the MSW management in the LAC countries is falling behind. This means that part of the blame is to be taken by the not so optimum waste governance structure in place.

A lack of proper institutional, financial, and participative strategies results in unstable or immature governance. It is interesting to note that a combination of all three of these aspects is responsible for the suboptimal status of MSW governance in the LAC region. After a survey conducted in cities in LAC, Hoornweg and Giannelli [25] listed the following as the main issues: the lack of a legislative framework and integrated MSW management systems (institutional issues), the lack of funding and efficiency (financial issues), and the lack of public-private partnerships (participative issues).

There are many ways to define governance. Hill and Hupe [26] defined governance as the way in which collective impacts are produced in a social system. Kooiman [27] said governance is used to solve problems and create opportunities, and the structural and processual conditions aimed at doing so. The Asian Development Bank [28] defined governance with the help of four basic elements: accountability, participation, predictability, and transparency. In general, governance refers to a process of collective social compromise by different social actors [29]. Social actors here can be in the form of central/local governments, the market, or various other members of the community. Governance is not a new concept. It has a history as old as the modern state. However, when the “sustainable development” concept emerged as a common goal of the international society in the 1980s and 90s, the topic received more attention as proper governance was thought to be an effective way to achieve sustainable development. Various concepts such as good governance and new governance were also subsequently introduced.

Current literature on the topic of governance is rich and provides various definitions for different types of governance. However, for the current discussion in this paper, it is beneficial to look at governance in a more classical way to recognize how much government control exists. For this purpose, governance is usually categorized into three types based on the type of main actors involved: bureaucratic governance, market governance, and network governance [30]. These categories help us to identify who is related, who should be responsible, and who should be considered. However, it should be noted that in the business of waste management, these three types of governance are not to be adopted exclusively. But they mostly appear in an integrated way, almost always based on the needs of public service delivery [31]. For example, waste collection can be simultaneously subjected to bureaucratic governance as well as to market governance. The three types of governance are briefly introduced in the following subsections.

3.1. Bureaucratic Governance

Bureaucratic governance (also known as hierarchy governance) is characterized by the following of rules, as defined by a hierarchic authority [32] such as a government. Authorities and rules are the organizing principles to achieve common social goals. Bureaucratic governance has a long history that began when the concept of a state was conceived. It can be an effective way to achieve goals in that the authority enforces the performance of a task and raises funds easily compared to other types of governance. However, when the authority is corrupt, there is a high possibility for governance to become ineffective.

Bureaucratic governance related to MSW management in the LAC countries suffers severely from the limitations in enforcing MSW management policies due to weak governmental power. The legislation on MSW management is very weak and MSW has traditionally been the responsibility of local municipalities which claim to have a lack of resources. Municipalities have been unable to establish financially self-sustaining services and this works as an obstacle, together with the lack of political and legal will to address the need for adequate waste treatment. Corruption and lack of long-term commitment are also serious challenges faced by local institutions. The roles, responsibilities, and the allocation of responsibilities are not clearly defined, often creating partial overlapping of authorities. For instance, in many countries, the ministries of environment and health frequently struggle with this issue over some legislation. Similar overlapping problems between two ministries could also occur for monitoring and controlling functions.

3.2. Market Governance

Market governance depends on the power of the market where individuals exchange according to what serves their interest [32]. As everyone pursues his or her own interests, theoretically speaking, it automatically guarantees efficiency and maximizes the interest of society. In this model, incentives and prices play the central role of social transformation [30]. Also, it relies on contracts and remuneration which encourage actors to perform. Market governance is attractive in that it achieves goals with minimum cost and often generates revenues. On the contrary, when the market does not work properly or if it is interrupted by other unexpected events, market governance becomes neither efficient nor effective.

Many in the LAC region do not see MSW as a resource. This has indirectly caused MSW to be considered uninteresting to the market governance. Public perception towards waste has also been negative. In some countries, someone getting a job in an MSW-related area is considered a punishment rather than a reward. As a result, markets which are related to waste management in LAC are underdeveloped and the private sector companies have a very low interest towards waste-related businesses. This directly influences negatively on MSW management because municipalities often need the assistance of private companies to collect and treat waste. Additionally, a poor financial situation prohibits investment in new technology or hiring more workers. The declining waste industry is damaging the profitability and efficiency of market governance.

3.3. Network Governance

Deficiencies in bureaucracy and the market led to the implementation of a new type of governance called network governance, which encourages the participation of the public as well as private entities/individuals. Network governance operates by acting in ways that are appropriate for some groups of which they are a part [32]. The key factors of network governance are norms and values. Also, it relies on customs and trust among members of society [33]. Network governance is a problem-solving process that people who are directly involved take part in. Theoretically, it is a democratic decision-making process; within the context of sustainable development and Public-Private Partnership (PPP), it is being emphasized a lot. However, network governance can take a long time to deliver tangible results.

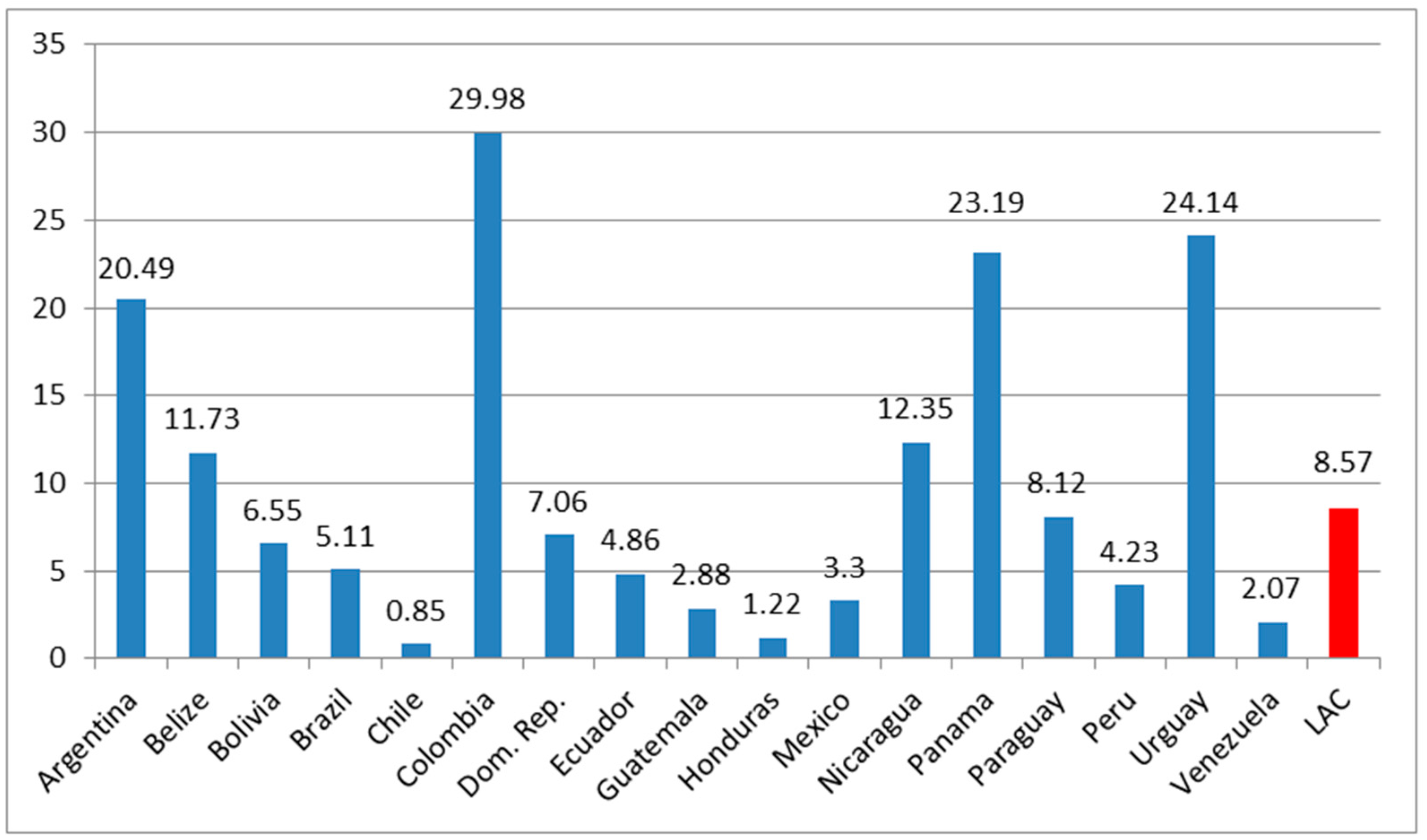

Issues related to waste pickers in the informal sector are both problems and at the same time opportunities for LAC countries in relation to network governance. Waste collection in this region is highly dependent on the staggeringly high number of waste pickers (Figure 3). They are responsible for 10 to 50% of waste collected and recovered in LAC [34]. In Buenos Aires alone, more than 40,000 waste pickers are involved in recovering cardboard and other recyclables on the streets, and their economic impact is estimated to be $178 million [35]. In the LAC region, an estimated 0.5–3.8 millon people are in the waste picking business [35,36]. Typically, waste pickers in the informal sector are characterized as small, labour-intensive, low-paid operations, often with low technologies, poor hygiene, and poor safety. They also often face environmental injustice and economic difficulties.

Figure 3.

Number of waste pickers per 10,000 inhabitants in LAC [19].

However, when waste pickers organize themselves to negotiate, they form an entity in network governance. Waste pickers are experts on providing primary collection and processing collected waste resources into intermediate or final products in local areas. They contribute to the cost reduction of local services, which municipalities are responsible for, by increasing landfill life or reducing the transportation cost, thus smoothening the transition to a circular economy. As waste pickers provide waste management services in all the corners of small local areas, they know their areas of service better than public administrators or policymakers do. Also, waste pickers are creative and innovative in that they utilize cost-effective measures to respond to market needs [37]. These imply that LAC countries with lots of individual informal waste pickers have potential in strengthening their network governance.

4. Improving MSW Governance: Best Practice Examples from the Region

In the previous sections, we have identified some of the challenges in MSW management in LAC. The objective of the rest of this paper is to identify some of the best governance practices that can be used to overcome these challenges or in the best case scenario, turn the challenges into opportunities. The quest for turning challenges into opportunities can in turn benefit these relatively large city populations in the LAC region, making it a blessing in disguise. If the correct combination of resource recovery options is put into action as an alternative to current direct disposal, on the one hand, the large populations in the cities will be able to guarantee the supply of the raw material needed for the process—the MSW. On the other hand, when proper MSW management schemes are introduced in the cities, it automatically assures service coverage to over 80% of the population in the whole region. The city-centric distribution of the population also makes MSW a point source of pollution, which is comparatively easier to handle than a diffused one.

Each region is unique and has its own characteristics. Governance functions better when the governing strategies are developed based on these regional characteristics. Therefore, the next few subsections present some best practice examples selected from the countries in the same region as potential solutions. For easy reference to the correct stakeholder groups, the discussion is presented according to the same governance types introduced before.

4.1. Improving Bureaucratic Governance with Better Billing Strategies

Cost accountability is a basic element to ensure efficiency and detect irregularities within the MSW services. It can be guaranteed through the use of unit cost indicators, which are used to determine budgets so as to ensure the financial, environmental, and social sustainability of the services. As discussed before, property tax is the dominant method of waste service billing in LAC. In contrast to this dominant method, collecting waste management fees along with those for other public services such as electricity, water, and sanitation is more efficient in terms of a higher return. Espinoza et al. [19] revealed that collecting the waste service dues together with the electricity bill is the method of the highest return. Adopting more efficient billing and collecting methods can certainly increase government waste management revenue.

One way is to establish and operate a public solid waste service company which has administrative and financial autonomy and to bill through this public company. One of the best examples in the region is the Municipal Public Urban Cleaning Company (EMAC-EP), which was created in 2009 to provide solid waste management services in the city of Cuenca, Ecuador. EMAC-EP was funded by the electricity bill. It is a financially efficient and environmentally friendly company that is also politically compliant with local legislation. It has its own fee structure regulated by municipal ordinance and the structure includes criteria for a collection fee, public cleaning fee, and collecting methods. The fee structure makes EMAC-EP one of the few financially self-sustaining solid waste service providers in LAC. It is able to recover its investment and operational costs, thus fairly achieving financial sustainability for the services rendered [19].

4.2. Opportunities to Strengthen Market Governance

4.2.1. Increasing Private Sector Involvement

To encourage the private sector to become involved in MSW management, it needs to be given enough incentives. Often, private companies are involved in the collection and transfer of wastes through a contract with municipal governments. Highly efficient markets can be achieved when local governments use best practices such as service contract transparency, awarding concessions to the best bidder, not using public resources for private use, not bowing down to bribery and favouritism, and implementing monitoring and supervision systems. A sound relationship between the municipal government and private sectors can maximize the function of market governance.

Microenterprises are another form of private sector organizations which have outsourcing contracts with municipalities, such as the ones in Lima and La Paz, as reported by Hoornweg and Giannelli [25]. They are characterized by having few employees, keeping costs low, using simple technologies, and promoting the participation of the community. Microenterprises collect and separate waste materials at the source or close to the point of generation [36]. These small enterprises are not only cost-effective, but also enable the provision of affordable services and generate employment in the community.

4.2.2. Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) as an Example

Article 12 of the Kyoto protocol to combat climate change defined a new scheme called the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), which can be defined as an economic scheme for climate adaptation activities [38]. Under CDM, a country with an emission reduction commitment implements emission reduction projects in developing countries and earns tradable certified emission reduction credits. This mechanism can work as an economic incentive to invest in MSW management projects. Brazil and Mexico are good examples and projects are mainly based on reducing greenhouse gas emissions from sanitary landfills with gas capturing, gas burning, or energy-use-systems for gas [39]. CDM can stimulate bigger enterprises with technology and capital to participate in MSW management by giving them an economic motive.

4.3. Potential of Network Governance as a Strategy

4.3.1. Inclusion of the Informal Sector

Individual waste pickers from the informal sector are already a key part of the resource recovery process, but they are not usually given the due credit. They contribute to the cause of sustainability at the grassroots level and provide a service to the local communities at an affordable cost [40]. However, since they do not represent an organized community, their wellbeing is always compromised when their work is at risk. In many countries, the legal framework does not recognize them. Some past examples have shown that in countries where the informal sector is organized in unions or cooperatives, it is easier to include them in the public strategy and policy development processes and absorb them into the network governance. In countries where this is not the case, additional efforts are needed to ensure their inclusion [41]. There are examples of such initiatives of creating official cooperatives or microenterprises to formalize the role of the informal sector. Zapata Campos et al. [42] reported one such example from Managua, Nicaragua, where the municipality and NGOs (both international and local) collaborated on involving the informal sector while implementing a project to provide a waste collecting service in informal settlements. That project supported waste pickers to create a cooperative collecting household solid waste in the neighbourhoods that are not accessible with modern waste trucks.

One more example comes from Peru. In 2013, the municipality of Villa El Salvador implemented a programme called “Progreseves” to promote waste segregation at the source (source separation). The municipality selected eight recyclers’ associations to cover the demand and incorporated all those who were working informally [43]. Each association was given a designated pick-up area. This encouraged waste pickers to join the formal associations that keep them working. The service users were also given an incentive to promote the collection service provided by the Progreseves programme, which was a monthly discount of 20% on collection cost called “green bonus”.

Another dynamic example of a scavenger cooperative movement comes from Colombia. The “Fundación Social” is a non-governmental organization that has been assisting Scavengers’ Association (Asociación Nacional de Recicladores) in the formation of cooperatives since 1986 [44]. There are other similar successful stories of scavenger cooperatives in the LAC countries such as in Costa Rica, Ecuador, Guatemala, Peru, and Venezuela. Over the last few years, the creation of such cooperatives has gained momentum in the region. According to Bonner [45], Brazil is the country with one of the largest waste pickers’ organizations.

Monitoring waste pickers’ activities is also necessary to measure their economic contribution to informal recycling. Doing so can help improve their conditions. When the real population of recyclers is identified, other more appropriate strategies can be designed to upgrade their living conditions. The recognition and integration of the informal sector can result in grassroots development not only in solid waste management, but also in poverty alleviation and environmental protection.

4.3.2. Increased Public Involvement through Incentives

To activate the waste management market, more public involvement is needed. Sometimes special programmes are needed to boost such activities. One example comes from Curitiba, Brazil, where the municipality initially purchased waste in exchange for transportation vouchers, which were later replaced with more attractive foods items. Through this programme, the amount of trash in the streets was reduced and waste could be treated as a resource. A similar garbage exchange programme was also reported in Cuauhtémoc, Mexico. In this case, six bags of garbage were exchanged for one bag of basic food items. The community was given the opportunity to suggest the type of food that they would like to see in the food bags [46]. These kinds of programmes help give MSW value, making it a resource.

4.3.3. Increased Public Engagement through Education

MSW management in LAC can also benefit from programmes designed to answer public needs, such as awareness raising campaigns and training courses on governance. These will raise the level of consciousness not only on the rights, but also the obligations, of all stakeholders. Incorporation of MSW management in the formal educational curricula is required. Waste management authorities should put more effort into creating more educational campaigns emphasizing human values and encouraging public participation in the planning and implementation stages. Overcoming public indifference and unsustainable practices requires effective communication, a broad public understanding of the requirements of MSW management, and active participation of all relevant stakeholders throughout all project stages [47].

Some LAC countries are now focusing on improving the environmental awareness of children who are one of the most important target groups. The programme topics cover environmental concerns, waste reduction, proper handling of MSW, and also some hands-on activities. These programmes have prospered in Brazil, Chile, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Mexico, Paraguay, and Peru. Programmes in Colombia and Brazil have persisted long enough to show that they are successful. The municipality of La Molina, Peru, established the “La Molina Ecologica”, a grassroots level programme that covers awareness campaigns which have enabled direct dialogue with families on day-to-day MSW issues [48].

5. Summary and Conclusions

LAC, with over 600 million inhabitants, is the region with the highest percentage of city-dwellers in the world. Already at a figure of over 80% and still increasing, the urban population is a must to consider when managing MSW in this part of the world. The less favourable financial and institutional issues have caused MSW management in LAC to fall behind. This paper attempted to look at the MSW management issues as well as example solutions from the governance perspective. For the ease of explanation, the governance concept was introduced as three types: bureaucratic, market, and network. A summary is presented below under each governance type, together with the main conclusions and/or observations.

Bureaucratic governance is defined by hierarchic authority, such as a government that organizes and commands to achieve a common social goal such as MSW management. Bureaucratic governance in MSW management in LAC suffers severely from the weak governmental power to enforce management policies, and the uncoordinated overlapping of the institutional overlapping of the subjects. Not being able to collect revenue for the services rendered is seen as one of the major obstacles. As a result, municipalities have not been able to establish financial sustainability for MSW management. The conclusions pertaining to the bureaucratic governance are as follows:

- -

- There is evidence to suggest that collecting dues for waste services together with the electricity bill is the method of highest return.

- -

- Forming a public solid waste service company which has administrative and financial autonomy and billing through a public service company could be another way to improve some aspects of the bureaucratic governance structure as showcased by the Municipal Public Urban Cleaning Company (EMAC-EP) in Cuenca, Ecuador.

Market governance depends on the power of market dynamics. In this model, incentives and prices play the central role and rely on contracts and remuneration to encourage actors. The negative perception of MSW in the LAC region has adverse effects on market governance. As a result, the private sector interest in MSW-related business is low. The main observations under this category are as follows:

- -

- Some examples from the region itself tell us that the best practices such as transparency in service contracts, award concessions to the best bidder, avoiding private use of public resources, avoiding bribery and favouritism, and implementing monitoring and supervision systems, can increase private sector participation.

- -

- Microenterprises that are usually characterized by fewer employees, lower costs, and simpler technologies represent another mechanism to enhance market governance in the region.

Network governance is a hybrid of the bureaucratic and network governance concepts, made to encourage the participation of local communities, non-governmental organizations, and individuals. Network governance has gained attention in LAC, especially because of its flexibility in forming public-private partnerships, as seen in the MSW business. Waste collection in this region heavily depends on waste pickers, who represent the informal sector. Network governance has given waste pickers an opportunity to be organized and legitimately linked to the MSW workforce. The key conclusions related to the network governance aspects of MSW management in LAC are listed below:

- -

- Network governance provides flexibility to design special programmes to activate the MSW management market and increase public involvement, as showcased by the “waste in exchange for transportation vouchers or food” campaign in Mexico.

- -

- The positive environment built through PPP also provides an ideal platform to answer public needs, such as awareness raising campaigns and training courses on governance.

Author Contributions

H.H. developed the initial philosophy for the research and the basic structure for the manuscript. S.R. contributed to the analysis related to a governance aspect with the political science background. S.C. and R.S. assisted in gathering and analyzing information, particularly from Spanish language documents. In general, all authors contributed to the writing process.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to recognize the gracious contributions of Stoyan Dimitrov (from Bulgaria and currently in Peru) and Irina Garcia (from Honduras and currently in Japan) to this paper. During the research internships conducted at UNU-FLORES in 2015, they both worked tirelessly to gather literature from the LAC region to prepare this manuscript. Many thanks also go to Atiqah Fairuz Salleh for her editorial work on the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Bank. WHAT A WASTE: A Global Review of Solid Waste Management. Urban Development Series Knowledge Papers; Paris, France, 2012. Available online: https://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTURBANDEVELOPMENT/Resources/336387-1334852610766/What_a_Waste2012_Final.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2018).

- Ikhlayel, M. Development of management systems for sustainable municipal solid waste in developing countries: A systematic life cycle thinking approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 180, 571–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rada, E.C.; Zatelli, C.; Cioca, L.I.; Torretta, V. Selective collection quality index for municipal solid waste management. Sustainability 2018, 10, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agamuthu, P.; Fauziah, S.H.; Khidzir, K.M.; Noorazamimah Aiza, A. Sustainable Waste Management–Asian Perspectives. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Sustainable Solid Waste Management, Chennai, India, 5–7 September 2007. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Urban Population. World Bank Staff Estimates Based on the United Nations Population Division’s World Urbanization Prospects. 2018. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.URB.TOTL?locations=ZJ&name_desc=false (accessed on 18 March 2018).

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Global Food Losses and Food Waste–Extent, Causes and Prevention; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ferronato, N.; Gorritty Portillo, M.A.; Guisbert Lizarazu, E.G.; Torretta, V.; Bezzi, M.; Ragazzi, M. The municipal solid waste management of La Paz (Bolivia): Challenges and opportunities for a sustainable development. Waste Manag. Res. 2018, 36, 288–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferronato, N.; Torretta, V.; Ragazzi, M.; Rada, E.C. Waste mismanagement in developing countries: A case study of environmental contamination. UPB Sci. Bull. 2017, 79, 185–196. [Google Scholar]

- Sepúlveda, J.A.M. Outlook of municipal solid waste in Bogota (Colombia). Am. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2016, 9, 477–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohee, R.; Mauthoor, S.; Bundhoo, Z.M.A.; Somaroo, G.; Soobhany, N.; Gunasee, S. Current status of solid waste management in small island developing states: A review. Waste Manag. 2015, 43, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ragazzi, M.; Catellani, R.; Rada, E.C.; Torretta, V.; Salazar-Valenzuela, X. Management of municipal solid waste in one of the Galapagos islands. Sustainability 2014, 6, 9080–9095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD/ECLAC/CAF. Latin American Economic Outlook 2017: Youth, Skills and Entrepreneurship; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chainey, R. Which Countries Waste the Most Food? Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2015/08/which-countries-waste-the-most-food/ (accessed on 20 March 2018).

- Grau, J.; Terraza, H.; Velosa, R.; Milena, D.; Rihm, A.; Sturzenegger, G. Solid Waste Management in Latin America and the Caribbean; Inter-American Development Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT). State of Latin American and Caribbean Cities–Towards a New Urban Transition; UN-HABITAT: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Municipal Solid Waste Management: Regional Overviews and Information Sources Latin America and the Caribbean. Division of Technology, Industry and Economics. Available online: http://www.unep.or.jp/Ietc/ESTdir/Pub/MSW/RO/Latin_A/Topic_b.asp (accessed on 20 March 2018).

- Ojeda Benitez, S.; Armijo de la Vega, C.; Ramírez Barreto, M. Formal and informal recovery of recyclables in Mexicali, Mexico: Handling alternatives. Resour. Conversat. Recycl. 2002, 34, 273–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, A.P.; Ramos Ridao, Á.; Zamorano Toro, M. Environmental diagnosis and planning actions for municipal waste landfills in municipal landfills in Estado Lara (Venezuela). Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2006, 12, 752–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, P.; Arce, E.; Daza, D.; Faure, M.; Terraza, H. Regional Evaluation of Municipal Solid Waste Management in Latin America and the Caribbean: 2010 Report; PAHO: Washington, DC, USA; AIDIS: São Paulo, Brasil; IDB: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Emilio Godoy. The Waste Mountain Engulfing Mexico City. The Guardian. 2012. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2012/jan/09/waste-mountain-mexico-city (accessed on 20 March 2018).

- Blight, G. Slope failures in municipal solid waste dumps and landfills: A review. Waste Manag. Res. 2008, 26, 448–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UN. Municipal Waste Treatment. Statistics Division, 2011. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/ENVIRONMENT/wastetreatment.htm (accessed on 20 March 2018).

- Boadi, K.O.; Kuitunen, M. Municipal Solid Waste Management in the Accra Metropolitan Area, Ghana. Environmentalist 2003, 23, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteman, A.; Smith, P.; Wilson, D. Waste Management: An Indicator of Urban Governance; UK Department for International Development: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hoornweg, D.; Giannelli, N. Managing Municipal Solid Waste in LAC: Integrating the Private Sector, Harnessing Incentives; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, M.; Hupe, P. Implementing Public Policy: Governance in Theory and in Practice; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2002; ISBN 0-7619-6628-5. [Google Scholar]

- Kooiman, J. Social-political governance: Overview, reflections and design. Public Manag. 1999, 1, 67–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asian Development Bank. Governance: Sound Development Management; Asian Development Bank: Mandaluyong, Philippines, 1995; ISBN 971-561-262-8. [Google Scholar]

- Hufty, M. Investigating Policy Processes: The Governance Analytical Framework (GAF); Research for Sustainable Development: Foundations, Experiences, and Perspective; Geographica Bernensia: Bern, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, G.; Frances, J.; Levacic, R.; Mitchell, J. Markets, Hierarchies and Networks; Sage: London, UK, 1991; ISBN 978-0803985902. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, W. Public Policy: An Introduction to the Theory and Practice of Policy Analysis; Aldershot: Brookfield, UK, 1995; ISBN 1852785535. [Google Scholar]

- Colebatch, H.K.; Larmour, P. Market, Bureaucracy and Community: A Student’s Guide to Organization; Pluto Press: London, UK, 1993; ISBN 0745307620. [Google Scholar]

- Ouchi, W.G. Markets, bureaucracies and clans. In Markets, Hierarchies and Networks; Thompson, G., Frances, J., Levacic, R., Mitchell, J., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 1991; pp. 246–255. ISBN 978-0803985902. [Google Scholar]

- Noel, C. Solid waste workers and livelihood strategies in Greater Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Waste Manag. 2010, 30, 1138–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medina, M. The Informal Recycling Sector in Developing Countries: Organizing Waste Pickers to Enhance Their Impact; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). Report on the Regional Evaluation of Municipal Solid Waste Management Services in Latin America and the Caribbean: Area of Sustainable Development and Environmental Health; PAHO: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S.; Ali, M. Partnerships for solid waste management in developing countries: Linking theories to realities. Habitat Int. 2004, 28, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations (UN). Clean Development Mechanism. Climate Change. 2014. Available online: http://unfccc.int/kyoto_protocol/mechanisms/clean_development_mechanism/items/2718.php (accessed on 18 March 2018).

- Lokey, E. Renewable Energy Project Development Under the Clean Development Mechanism: A Guide for Latin America; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 9780415849302. [Google Scholar]

- Annepu, R.; Mitchell, K. Be Waste Wise. Available online: http://wastewise.be/2013/10/integrating-informal-waste-recycling-sector-latin-america/ (accessed on 28 May 2014).

- Hyman, M. Guidelines for National Waste Management Strategies: Moving from Challenges to Opportunities; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2013; ISBN 978-92-807-3333-4. [Google Scholar]

- Zapata Campos, M.J.; Zapata, P. The travel of global ideas of waste management: The case of Managua and its informal settlements. Habitat Int. 2014, 40, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazán, M. Vecinos, Recicladores, Municipalidad y ONG: La Comunicación en Tension. 2015. Available online: http://tesis.pucp.edu.pe/repositorio/handle/123456789/6259 (accessed on 18 March 2018).

- Terraza, H.; Sturzenegger, G. Dinámicas de Organización de los Recicladores Informales Tres casos de estudio en América Latina. NOTA TÉCNICA No. 117; Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bonner, C. Waste Pickers without Frontiers. In Proceedings of the First International and Third Latin American Conference of Waste-Pickers, Bogota, Colombia, 1–4 March 2008. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Solid Waste Management Volume II: Regional Overviews and Information Sources; International Environmental Technology Centre: Osaka, Japan, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Schübeler, P. Conceptual Framework for Municipal Solid Waste Management in Low-Income Countries; SKAT: Gallen, Switzerland, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Goméz, R.; Flores, F. Ciudades Sostenibles y Gestión de Residuos Sólidos. Agenda 2014. Propuestas para Mejorar la Descentralización; Universidad Del Pacífico: Jesús María, Peru, 2014. [Google Scholar]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).