Abstract

Assessing product circularity performance is not straightforward. Meanwhile, it gains increasingly importance for businesses and industrial practitioners who are willing to effectively take benefits from circular economy promises. Thus, providing methods and tools to evaluate then enhance product performance—in the light of circular economy—becomes a significant but still barely addressed topic. Following a joint agreement on the need to measure product circularity performance, this paper provides an overview of mechanisms aiming to help industrial practitioners in this task. In fact, three existing approaches to measure product circularity performance have been tested on an industrial case study and criticized regarding both their applicability in industry and their accordance with circular economy principles. Although these methods and tools deliver a first and rapid trend of product circularity performance, the whole complexity of circular economy paradigm is far from being considered. In addition, operational guidance for engineers, designers or managers to improve their products in a circular economy context are missing. As a result, both recommendations for industrial practitioners and guidelines for the design and development of new frameworks, tools and indicators aiming at measuring product circularity performance are provided. This includes cornerstones, key requirements and practical implications to support enhanced circularity measurement that will be developed in further work, accordingly to circular economy paradigm and industrial reality.

Keywords:

circular economy; product circularity; measurement; indicators; tools; critical analysis; case study 1. Introduction

Circular economy is not fully a new concept but is rather based on a combination of fundamental and founding concepts such as, according to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF) [1], Industrial Ecology, Biomimetics, Natural Capitalism, Regenerative Design, Cradle to Cradle, and Blue Economy. In accordance with Sauvé et al. [2], what is new is the momentum that this concept is gaining among business practitioners (e.g., Renault, Caterpillar, Danone, Cisco), consultancy firms (e.g., McKinsey Global Institute, Accenture Strategy), governments (e.g., China and European Union), non-governmental organizations or associations (e.g., Ellen MacArthur Foundation), and academics (e.g., teaching programs, international conferences or special issues of journals related to circular economy) [3,4,5,6,7,8]. A particular interest of the circular economy concept lies in its compatibility and consistency with sustainable development—through its three associated pillars. Indeed, it aims directly not only at economic benefits (e.g., value creation and savings by reducing the purchase of primary raw materials), but also at environmental benefits (e.g., impact reduction) and indirectly at social benefits (e.g., job creation) [6,7]. As such, companies and collectives are increasingly willing to move towards more circular and sustainable economic and business model as a way of commercial differentiation, competitive advantage and potential growth with economic spinoffs. These are the reasons why industrial actors, non-expert in circular economy, are requiring support and guidance in their shift from a linear to a more circular economy. As key performance indicators (KPI) are widely used and acknowledged in industrial practices [9], developing appropriate circularity indicators appears to be relevant in the context of circular economy transition. To date, this segment of circularity measurement is mainly handled and operated by consultancy firms, that are not strongly connected to rigorous academic and scientific research methods, relying upon their proper business and marketing expertises (e.g., the Circle Scan & Circle Assessment developed by Circle Economy cooperative [10,11] or the Closed-Loop Calculator developed by Kingfisher [12]).

While benefits and opportunities of circular economy are appealing, challenges for industrial practitioners to shift for their businesses and products into more circular practices still exist. Actually, companies, institutions and researchers agree on the need to assess circularity at several and complementary systemic levels, as it will be detailed in Section 2. One central question then emerges: during design or re-design phases, how to assess the circularity potential of a product, component or material, all along the lifecycle, and throughout the value chain? Producing frameworks, methods and tools to answer this issue is essential, as a first step, to then efficiently improve the circularity of goods. This paper provides an overview of current ways to measure product performance in a context of circularity. The methods used for this paper consisted of both a literature review and a case study. One of the main significant aspects of this research work lies in the experimentation and critical analysis of these different existing tools through the industrial case study. As a result, this paper delivers not only recommendations for industrial practitioners but also guidelines for the design of frameworks—including tools and indicators—aiming at an enhanced product circularity measurement. Indeed, key requirements are highlighted to support the development and/or validation of new and more advanced tools and indicators that will assess product-level circularity performance.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows. After highlighting the need for circularity indicators, circularity measurement at different implementation levels is detailed in Section 2. Through the case study, test and critical analysis of three existing tools are performed in Section 3. Based on identified limits and on insights from literature, practical implications and proposed requirements for product-level circularity measurement are discussed in Section 4. Finally, Section 5 summarizes the main findings and opens up future perspectives for both industrial practitioners and researchers on the road towards product circularity assessment, improvement and monitoring.

2. Literature Review—The Measurement of Circularity, an Area in Question and in Development

The research methodology utilized in this paper is a literature review [13]. This was conducted first in order to get the current knowledge and practices in terms of product circularity measurement. The research conducted was based on both academic articles and non-academic organizations contributions. As recently stated by Geissdoerfer et al. [14]: “the inclusion of non-peer-reviewed articles is appropriate since circular economy is a new area of research, and (…) has not been extensively addressed by peer reviewed articles” contrary to areas of research such as recycling or sustainability. On the one hand, the focus on peer reviewed papers ensures scientific soundness. On the other hand, research works or projects carried out, as well as methods, tools or indicators developed by other organizations (such as the Ellen MacArthur Foundation) involved in the circular economy transition and working closely with businesses could reflect current industrial reality and needs regarding product circularity, and therefore bring additional meaningful insights.

In this light, the following data sources have been examined: Science Direct, Web of Science, SAGE, Springer, Taylor & Francis, Google Scholar, Google, Ellen MacArthur Foundation, Institut de l’Economie Circulaire (French Institute working on the circular economy), ADEME (French Environmental Agency). Keywords included: “circular economy” OR “circularity” AND “indicator” OR “measurement” OR “assessment”. The selection process was as it follows. First, based on scanning titles, abstracts and/or short contents, works—including peer reviewed academic journals, conference papers, research reports, postgraduate dissertations, books, websites and tools—which were considered as non-relevant regarding product-level circularity measurement have been discarded. Then, those which were dealing directly with or getting indirectly connections with product circularity measurement have been looked at extensively and critically.

2.1. Positioning on Circular Economy Definitions: Prerequisite for the Rest of This Article

A good understanding of the main definitions of circular economy proposed by major organizations and academics, and positioning ongoing work in relation to these definitions, are suitable as a first step before analysing the tools, proposing and discussing requirements for not only an efficient but also an effective measurement of products’ circularity in order to support progress towards a more circular economy.

To date, there is no standard definition of the circular economy concept. However, the different definitions of Economy Circular, proposed or established by major organizations and academic researchers, share much in common, tend to formalize and converge towards the same paradigm [15]. The CIRAIG performed an extensive literature review and inventory of key circular economy definitions [16]. All circular economy definitions agree that circular economy is definitely opposed to the linear model “make-take-waste”. In addition, circular economy is looking for a better management of resources throughout the lifecycle of systems and it is characterized by closed loops, promoting maintenance, reuse, remanufacturing and recycling.

In this paper, as a basis for analyzing the existing tools, we will refer at the circular economy definition proposed by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, including five fundamental characteristics (design out waste, build resilience through diversity, work towards energy from renewable sources, think in systems, think in cascades) and four building blocks (circular product design, innovative business model, reverse cycles, enablers and system conditions) [3]. Particularly, to fit totally with the circular economy paradigm, system thinking is fundamental. Indeed, according to Balanay and Halog [17], systems thinking is central in circular economy, because designing out wastes and closing the loop needs a holistic understanding and support for broad-based acceptance and success of interventions towards circularity. Moreover, the Ellen MacArthur Foundation butterfly circular economy model is one of the most acknowledged and used in businesses, as well as in academic circles [18].

2.2. Joint Agreement on the Need to Assess Circular Economy Performance

To follow and successfully achieve the transition towards a more circular economy, it is becoming essential for actors and industrial practitioners—such as engineers, designers, managers—to get suitable methods and tools, including indicators, to measure and quantify this progress [19,20]. In fact, the interests of such indicators lie in their ability to summarize and concentrate the great complexity of our dynamic environment, in order to manage a comprehensive amount of meaningful information [21]. Furthermore, indicators are a way to assess change and could therefore be used as an important tool to support the evolution from a linear economy to a more circular one [22]. In a report about circular economy and metals recycling, conclusion is made on the necessity, due to the current lack notices in this area, to develop methods and tools that aim at assessing and monitoring overall performance of the circular economy for the environment [15]. According to Kingfisher, one system cannot get more closed loop unless knowing how closed loop it was in the first place [12]. In fact, it should be relevant to measure circularity degree of current systems, processes and products to evaluate the remaining distance to achieve a self-sustaining economy, truly circular [23]. On the other hand, with the current increasing attention about sustainability and sustainable development, it will not be surprising that a quantifiable sustainability rating would one day be required for all the manufactured products via some regulations [24]. A similar decision leading to a regulatory framework and mandatory rates will also be plausible and conceivable for the circular economy. Indeed, several laws related to circular economy are slowly but surely beginning to emerge, namely in China, in the European Union or more recently in France (Section IV of the Act concerning the Energy Transition to Green Growth aims to promote Circular Economy). Yet, in the European Union, circular economy evaluation systems and their associated methodology are still developing [25]. Last but not least, in agreement with the European Academies Science Advisory Council (EASAC) [26], one of the critical questions linked to the circular economy is how we should measure its performance. For the EASAC, indicators are essential for circular economy assessment at all levels.

2.3. Different Levels of Circular Economy Measurement

Circular economy models and implementations are usually performed at three systemic levels. Circular implementation at macro level fits with city, province, region, nation, meso level fits with eco-industrial parks, while micro level corresponds to single company or consumer. Balanay and Halog [17] confirmed this classification: circular economy macro-layer referring to society, meso-layer to inter-enterprise and micro-layer to enterprise. Banaité [25] also analysed and clustered circular economy evaluation systems into three levels: evaluation at micro level for single company or consumer, evaluation at meso level for symbiosis association, and evaluation at macro level for city, province, region or country.

Through their analyses, the EASAC [26] found out that many available indicators may be appropriate for monitoring progress towards a circular economy. These indicators were grouped into sustainable development, environment, material flow analysis, societal behaviour, organizational behaviour and economic performance. However, product circularity performance was not directly considered in these indicators. Likewise, most circular economy indicators reviewed by Ghisellini et al. [27] are standing at macro-level (nation level) and meso-level (inter-firm level) but barely at micro-level.

For instance, at a macro level, the Waste & Resources Action Programme (WRAP) [28] estimated that 19% of the UK economy is circular in 2010. Based on a material flow analysis, this circular score of 19% relates to weight of domestic material input (600 million tonnes) entering the economy compared with the amount of material (115 million tonnes) recycled. On the other hand, China had released its first Circular Economy Evaluation Indicator Systems [19] that provides two separate sets of indicators: one at a micro-level for the general evaluation of the circular economy on development for both individual region and national-level analysis to provide guidance for future circular economy development planning; and one at meso-level to assess the state of circular economy development at the industrial park level.

According to Geng et al. [19], although the application of this indicator system may bring certain benefits, problems and challenges still exist, including for example, the lack of indicators for businesses. Additionally, circular economy evaluation at micro level is actually based on cleaner production and green consumption what is not full circular economy approach [19]. Indicators that claim to be circular economy indicators at micro level do not encompass the whole complexity of circular economy and all possible end-of-life options to close the loop. For instance, the evaluation indicator system of circular economy in iron and steel enterprises that includes 13 indicators grouped into 3 categories (resource input and consumption index, resource flow and recycling index, resource output and management index) is mainly focused on resource efficiency through recycling and therefore does not consider other end-of-life scenarios [29]. Likewise, the quantitative Evaluation of Circular Economy Based on Waste Input-Output Analysis composed of 14 indicators is mainly focused on waste production/recovery and lacks of systemic consideration [30].

Huamao and Fengqi [31] explored circular economy from the viewpoint of the system theory. From this standpoint, an important characteristic of the circular economy is its layers. All the layers of circular economy are “interdependent, interactive and mutually restricted”. Actually, As Huamao and Fengqi pointed out: “the layers of circular economy are to influence and interact with each other, and the higher layers take the lower layers as the basis and guide the development of the latter”. Besides, according to Lieder and Rashid [18], the circular economy level of discussion is highly granular and rarely touching operational level. Ghisellini et al. [27] confirmed that current indicators are barely focused on the circularity at the scale of individual products. In addition, a lack of connection between the three layers of circular economy implementation is noticed.

Thus, a more specific or detailed level could be relevant to further focus on the very core and essence of circular economy, which is the circulation and recirculation of products and materials in (open or closed) loops. For instance, such focal point will be helpful for companies—manufacturers and industrials practitioners—willing to manage and improve the circularity of products and components they design, develop, manufacture or sell. That is the reason why the authors suggest a fourth circularity level: a nano level as a more refined level focusing on the circularity of products, components and materials, included in three wider systemic levels, all along the value chain and throughout their entire lifecycle. That nano level—i.e., an operational and product-level including components and materials—could serve as a common denominator within these three levels, and could enable not only to make the links between these levels but also to have a closer look at the effective performance of circular economy implementation.

Methods, tools and indicators to assess product circularity, developed by researchers and organizations for companies, at that nano level, will be analysed in further details in the following sub-section.

2.4. Existing Indicators, Methods and Tools to Measure Product Circularity

According to a report from European Environmental Agency (EEA) published in 2016 [32], there is at present no recognized way of measuring how effective the European Union, a country or even a company is in making the transition to a circular economy, nor are there holistic monitoring tools for supporting such a process. In the same way, only a small number of published studies design or discuss circular economy indicators, therefore calling for additional research [27]. Likewise, in agreement with the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, there are no official or recognized indicators, methods and tools to measure company performance in the shift from a linear economic model to a more circular one and neither tools to support and follow that transition [33]. Indeed, circular economy indicators are at an initial stage of development [34]. Existing indicators and assessments have not the capacity to capture the entire circular economy performance of products [35]. Chinese researchers also acknowledge that current indicators were not designed considering systemic aspects, closed-loops or feedback features that characterize circular economy paradigm [19].

Franklin-Johnson and her colleagues, within their work published in 2016 “Resource Duration as a managerial indicator for Circular Economy performance”, provide a novel indicator for environmental evaluation performance linked to circular economy, on the basis of which circular economy central point is value creation through materials retention in a loop of high added value [35]. The longevity indicator called “Resource Duration” measures material retention based on the amount of time a resource is kept in use, regarding three following aspects: initial lifetime; durability earned through reuse or refurbishing; durability gained thanks to recycling. This non-monetary indicator is only focused on environmental efficiency of resources and could therefore be used as a local or complementary indicator, rather than a global one which could embrace the whole circular economy paradigm.

On the other hand, Amaya [36] contributes to provide a framework for designers willing to quantify environmental benefits offered by closed-loop strategies for industrial products, considering both remanufacturing and product-service-system (PSS) solutions. The objective was to provide easy to use methods and tools for designers to allow them quantifying the environmental benefits related to the use of a closed loop strategy. Amaya’s model has been developed to assess from an environmental point of view the data of the operations and activities around products’ lifecycle with final non-classic disposal scenarios (e.g., remanufacturing as end-of-life scenario or multiple uses by service offers system as a business strategy). Nevertheless, economic dimensions are neither tested nor considered in the case studies developed. With only environmental arguments but without any cost considerations, companies are not likely to enter in a remanufacturing or PSS business model.

Starting from these observations, academic and organizations—like the European Commission or the Ellen MacArthur Foundation—are well aware of this lack of circularity indicators for products and are willing to fill these gaps by initiating projects that aim at measuring the circularity of products and the transition towards this circularity. For instance, the Ellen MacArthur Foundation decided to launch the “Circularity Indicators Project” in May 2015. According to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, the benefits of proper circularity indicators could be significant: from decision-making tool for industrial practitioners, to internal reporting, through rating or evaluation of companies. For instance, managers, designers and engineers could take into account circularity as one of the indicators for design decisions. In addition, such indicators could compare different products, or facilitate the setting of product circularity targets. However, recent models developed to achieve circularity measurement of industrial products present notable limits. Indeed, in 2015, the CIRAIG [16] reviewed and pointed out the limitations of two frameworks aiming at measuring circularity: the Material Circularity Indicator (MCI) [33] and the Circle Assessment (CA) [11]. In this paper, the MCI will be analyzed, tested and critiqued. Yet the CA is out of the scope of this paper since, according to email exchange with Shyamm Ramkumar—knowledge and innovation manager at Circle Economy to get access to the online survey—the CA is not a tool that is used for analyzing products throughout the whole value chain, but rather organizations [10,11]. In our study, in addition to the MCI, two other tools—that have been identified as particularly conceived for product circularity evaluation—will also be reviewed, experienced and critically examined: the Circular Economy Toolkit (CET) [37] and the Circular Economy Indicator Prototype (CEIP) [20]. A more detailed description of these three tools is elaborated in the next section.

3. Results—Comparison of Existing Tools to Measure Product Circularity

In order to complement the findings from the literature review analysis, a case-study approach was adopted to allow a deeper insight into the desired and required features for an efficient and effective assessment of product circularity performance. Importantly, experiments and analyses performed through the case study aim at providing additional and meaningful information to: (i) guide industrial practitioners in their products circularity assessment; and (ii) establish a list of key features for the development of new frameworks—including indicators and tools—aiming at an enhanced measurement and monitoring of product circularity potential.

3.1. Tools Description, Characteristics, and Modus Operandi

Three existing tools, available online or on-demand for free, aiming at measuring product performance in a context of circular economy, have been selected through the literature review analysis. Tools description, characteristics and operating mode are synthesized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Tools description, characteristics and operating mode.

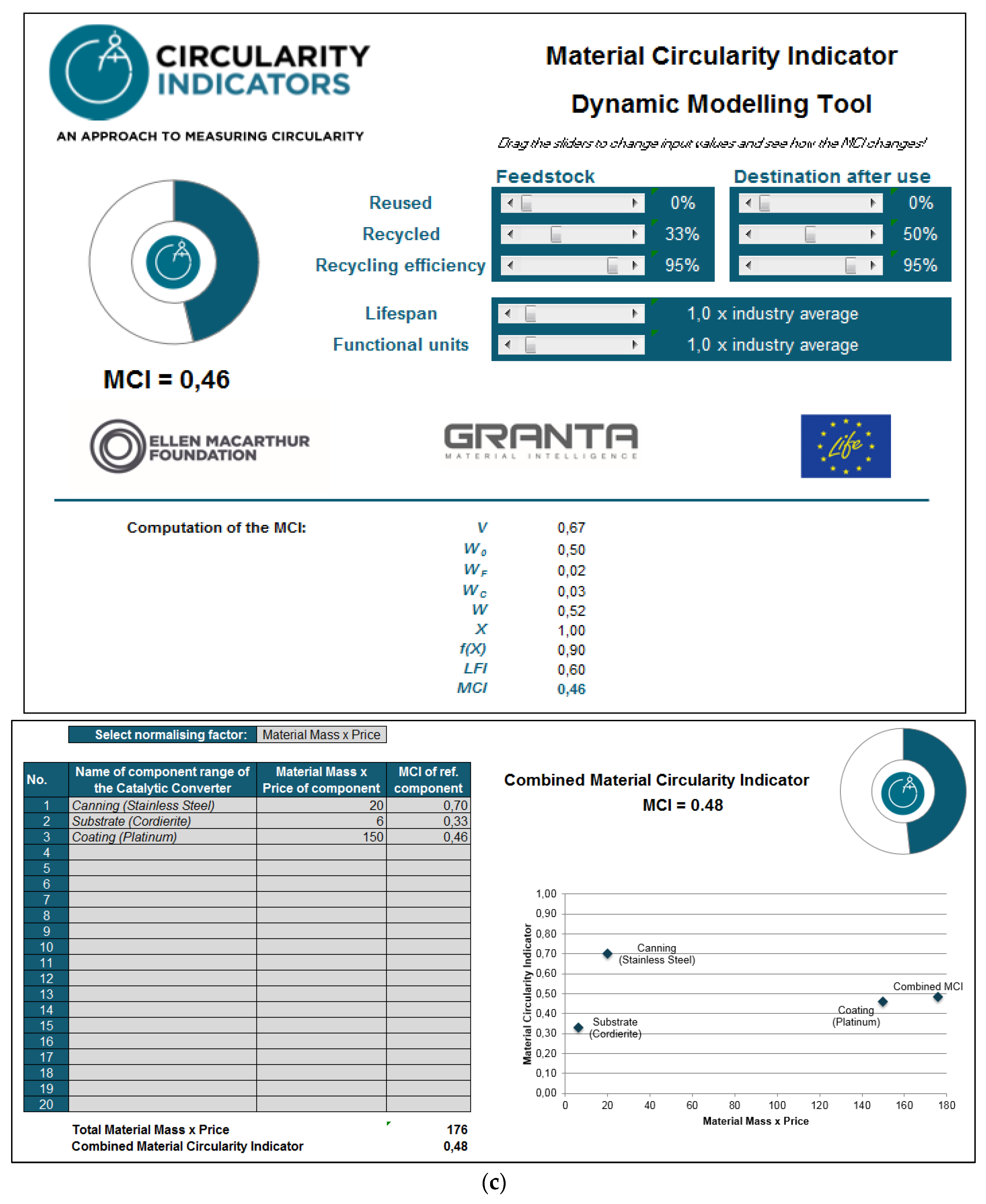

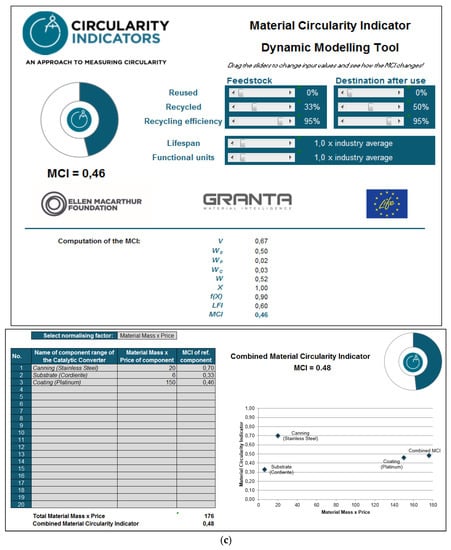

The Material Circularity Indicator (MCI) is describes by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation [33] as a tool for European companies to assess their products and business models performance in a context of circular economy. This indicator is particularly intended for use in product design but could also be used in internal reporting or for procurement and investment decisions. The indicator developed is based on an Excel calculation sheet available online for free. To evaluate the circularity performance at the product level, a spreadsheet tool is also provided (as shown in Figure 1c) in order to aggregate multi-materials as well as some guidance on normalizing factors for individual products’ weight within a general portfolio (e.g., revenues, product mass, and raw materials costs).

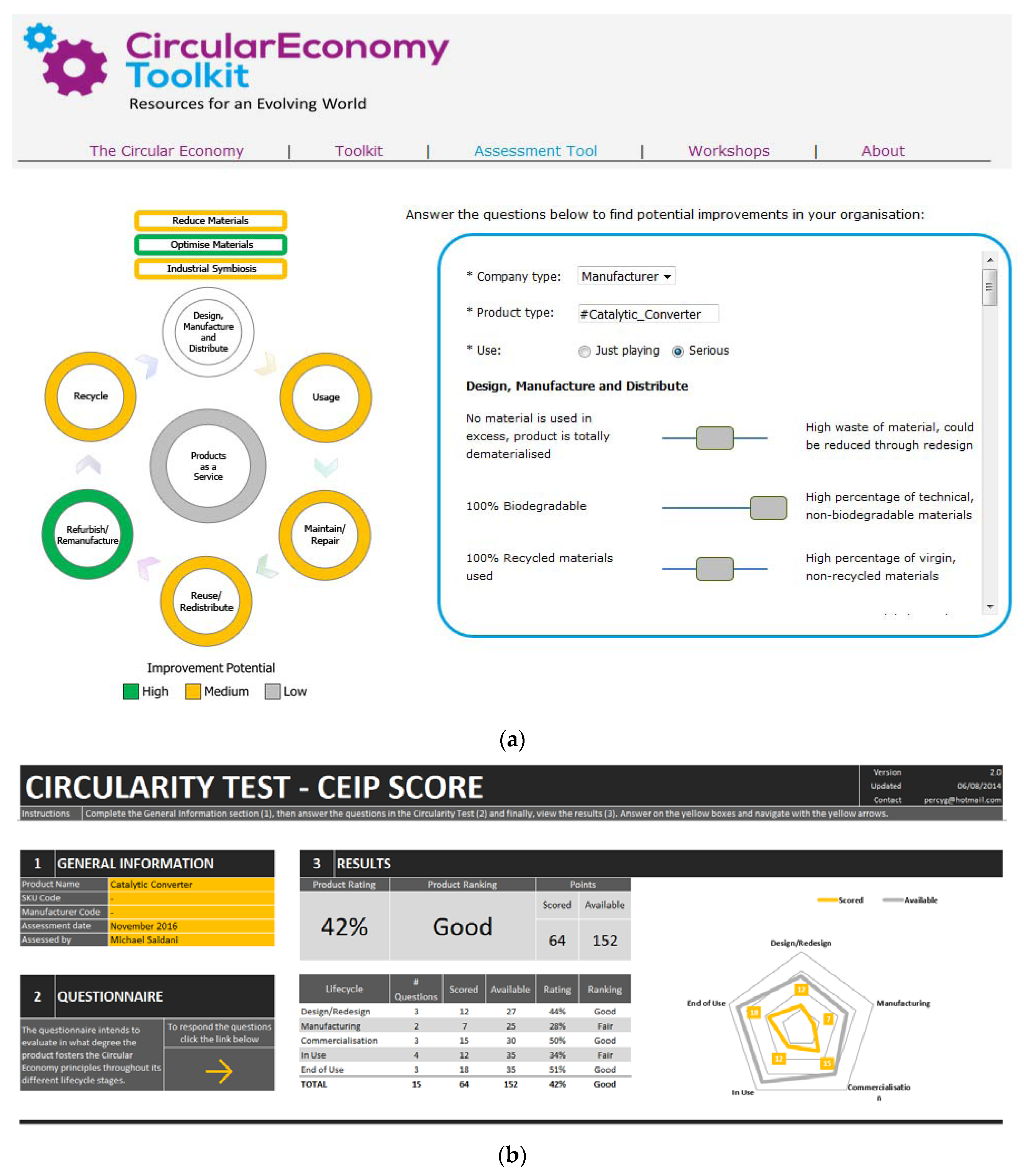

Figure 1.

Illustrations and interfaces of the three free tools experienced to measure product circularity: (a) Circular Economy Toolkit (CET) [37]; (b) Circular Economy Indicator Prototype (CEIP) [20]; (c) Material Circularity Indicator (MCI) [33].

The Circular Economy Toolkit (CET) is an assessment tool to identify potential improvement of products’ circularity [37]. This tool is also freely accessible online. It consists of answering—in a trinary format (yes/partly/no or high/medium/low)—33 questions divided into 7 sub-categories, similarity to the lifecycle stages considered in an environmental qualitative assessment: 7 questions related to design, manufacture and distribute; 3 related to usage; 6 related to maintenance and repair of the product; 3 related to reuse and redistribution of the product; 10 related to refurbish and remanufacture; 2 related to product-as-a-service; 2 related to product recycling at end-of-life.

The Circular Economy Indicator Prototype (CEIP), developed by Griffiths and Cayzer [20], available on demand, aims at evaluating product performance in the context of circular economy. The CEIP is designed on an Excel calculation sheet. The CEIP uses a points-based questionnaire. Fifteen weighted questions are divided into 5 lifecycle stages, namely: design or redesign; manufacturing; commercialisation; usage; and end-of-life. Once the questionnaire is completed, one gets an overall score of the product circularity performance plus a spider diagram showing circularity performance across different parts of the lifecycle.

3.2. Case Study: Tools Experimentation Based on a Real Industrial Product

To test and compare the outputs provided by each tool, the same industrial product—and its associated dataset—is used. The industrial product used in this case study in a catalytic converter that equipped heavy off-road vehicles such as excavators or mobile cranes. The manufacturing company, one of the European leader in machinery construction equipment, seeks to improve the traceability and circularity of their products, notably their catalytic converters considered as a key component due to high value of precious metals—platinum—containing inside. This system is significant for conducting the present case study because, according to Hagelüken et al. [38], while metallurgical recovery rates for platinum group metals from automotive catalysts may be over 95%, the effective recycling rate is currently around 60%. The catalytic converter is a mandatory equipment to fit with emissions regulations. The platinum is the core element of this system as it allows the transformation and catalysis of toxic pollutants into less or non-toxic gases. As the emissions regulations are increasingly strict, the quantity of precious metal is likely to rise. As such, the company is willing to close the loop of catalytic converters they design and develop, to maintain and recover the platinum contain in their product in order to mitigate the purchase of primary, precious and expensive raw materials, submitted to increased price volatility.

As inputs, data and information about the pre-life (e.g., bill of materials, product design features, production process, logistic aspects), and the life (e.g., lifespan, market destination, business model related to the product) of the catalytic converter were provided by manufacturer, suppliers and through market analysis. Assumptions about the end-of-life (e.g., destination after use, collection rate, treatment facilities, and recycling efficiency) of the catalytic converter were made based on worldwide and European statistic and discussion with the company. As such, inputs required by each tool were filled.

As outputs, results provided by the three tools experienced on this catalytic converter are illustrated in Figure 1. The Circular Economy Toolkit (CET) gives following recommendations to enhance catalytic converter circularity performance: high improvement potentials regarding product remanufacturing and materials optimization to enhance circularity, and medium improvement potentials related to usage, maintain, reuse and recycle phase. The Material Circularity Indicator (MCI) delivers a MCI score for each material used in the product. The three main materials of the catalytic converter were assessed: a MCI score of 0.70 for the stainless steel, 0.33 for the cordierite, and 0.46 (as shown in Figure 1c) for the platinum. The aggregated MCI score for the product, based on a normalizing factor that is the material mass multiplied by the material price, is 0.48. This combined MCI score is close to the score provided by the Circular Economy Indicator Prototype (CEIP): 42% (as shown in Figure 1b) which is considered as a “good” circularity performance according to the developers of the tool [20]. Moreover, the CEIP provides a table and a radar diagram detailing the circularity performance scores for each lifecycle stage.

3.3. Critical Analysis: Strengths, Weaknesses and Limitations of Existing Tools

These three tools share the advantages of being user-friendly, even for the non-specialist of circular economy, and time-efficient providing a first overview of product circularity performance. More precisely, the CET provides a first trend of improvement opportunities. The main advantage of this tool is that it considers both business opportunity and product design in the qualitative assessment. Notably, this tool assesses business opportunities (including financial viability and market growth potential) through possible extensions—according to inputs provided—of following services: maintain/repair, reuse/redistribute, refurbish/remanufacture and products as a service, as illustrated partly in Figure 1a. The CET online platform is also easy to understand even for non-expert in circular economy. On the other hand, The MCI is interesting to assess flow material potential of products circularity with relatively small amount of inputs data. Therefore, it could effectively be used by industrial practitioners to compare product circularity performance with different material combinations. Eventually, the CEIP presents the following strengths: ease of use, simplicity, speed, and the fact it could be used as an effective metaphor for the diffusion of circular economy principles in industrial practices.

However, the three tools have both weaknesses and limitations in the measurement of product performance in the light of circular economy. First, the Circular Economy Toolkit may be seen as too superficial to encompass the actual complexity of circular economy, in the way this toolkit is similar to a qualitative environmental checklist assessment with a trinary-based questionnaire. With the ternary scale, the user has the habit to put the cursor in the middle. In addition, some questions could lead to different interpretations (e.g., what is considered as many or few mechanical connections?). On the other hand, the MCI is not sufficient by itself to evaluate effective circularity of a given company and several products or components. Specifically, by standing only at the material scale contained in products or components, several essential aspects that are relevant to make progress towards a more circular model are not taken into consideration. For instance, these include modularity, upgradability, connectivity, easy disassembly or design for preventive maintenance of products that are recognized at enablers of an efficient circular economy. Interactions with other components (optimizing systems rather than components is the one of the key paradigm of circular economy) are not taken into consideration. Collaborations between stakeholders, inside the actors network, or reverse logistic, which are also crucial elements for a strong and functioning circular economy are either not explicitly considered. The scope of the MCI is narrower than what circular economy stands for, such as systems thinking. Last but not least, the MCI does not explicitly favor closed loops, that is to say, more granular levels of recovery beyond recycling and reuse, such as remanufacturing or refurbishment. It is assumed that the mass of the product does not change from manufacture to the end of use. In particular, this means that no part of the product is consumed, degraded or lost during its use. In addition, downcycling, i.e., the material quality loss in the recycling process is not taken into account. Eventually, the CEIP interpretation through a single score hides the true circular economy complexity. The binary scoring system used for some question could be quite reductive for some questions. Authors of the CEIP [20] acknowledge a superficial commitment with decision-makers and that the reliability of the questionnaire is based on the case study specific context: the 15 questions are mainly focused on the manufacturing and end-of-life stages of the product lifecycle, and therefore neglect certainly other circular economy crucial aspects. Indeed, several attributes suitable to move towards an efficient circular economy of products are not taken into account such as, modularity, design for disassembly, upgradability, used of new technology or connected devices: for instance, sensors to enable product traceability.

In a nutshell, even if these tools provide a first and rapid overview of product circularity performance, they do not cover all aspects of the circular economy and miss some important elements. Furthermore, they do not deliver practical or operational guidance for industrial practitioners to improve the product circularity of their products. As such, there is a lot of room for improvement regarding existing tools assessing product circularity performance. Additionally, to limitations highlighted below, authors of existing tools acknowledge the need for further investigations and developments in the area of product performance in a context of circular economy. As an example, the developers of the CEIP [20] foster not only to consider deeper the trade-off between simplicity and engagement with decision-making, but also to expend the design of circularity indicators to other industrial sectors.

4. Discussion—Proposed Requirements, Practical Implications and Recommendations

In this section, success conditions, required and desired features for an effective measure of product circularity performance are discussed. First, key requirements are proposed for the design of frameworks—including indicators and tools—aiming at an enhanced product circularity assessment. Thereafter, practical implications and guidelines are provided as a support to the development and implementation of such frameworks. In addition, recommendations are delivered for industrial practitioners on how to proceed in their product circularity measurement and monitoring.

4.1. Proposed Requirements for Product Circularity Measurement Framework

Based not only on the findings revealed through the experience of existing tools—i.e., their strengths, weaknesses and limitations regarding circular economy principles and industrial applicability—but also on acknowledged and well-funded recommendations from literature review, requirements for properly measuring product performance in the light of circular economy are highlighted. Basically, future enhanced frameworks for product circularity assessment should both share the same advantages of existing tools reviewed and fill their limitations—i.e., address and overcome the weaknesses pointed out.

The core question is indeed to define what are the ideal, desired or required features for designing a framework aiming at product circularity measurement and monitoring. One has to bear in my mind that such a framework is mainly intended to industrial practitioners that is to say mainly to engineers, designers and managers responsible in the design and development of products. Saidani et al. [39] translate industrial practitioners’ needs into eight criteria for selecting most suitable eco-design tool for improvement purposes fitting with companies’ constraints and context. With a similar mindset, ideal product circularity measurement tool features are derived from complementary industrial and academic works.

First, the framework should not only be integrated and holistic [40] to fit with circular economy paradigm but also, adaptative, modular to be compatible or plug-in with complementary existing methods and tools in order to use the strengths of different previous works. Then, it would be better if the circularity measurement tool could work at the scale of thousands of products [12]. For the European Environmental Agency (EEA) [32], because of the complex dynamics governing the transition, the monitoring framework needs to be flexible, allowing the adaptation of indicators and focus areas to maintain its effectiveness throughout the evolution towards more circular practices. Additionally, taking into account the entire value chain may result in the creation of a considerably greater resource efficiency potential [41]. Hence, it should be lifecycle thinking and system thinking [17]. In addition, Arnsperger and Bourg [23] reflect on the foundations of circularity indicators for an economy authentically and genuinely circular. They conclude a circular indicator, or a set of circular indicators, should definitely be systemic by design so that to prevent any major rebound effects or negative impact transfers (e.g., circular improvements focused only on micro level would lead to deterioration to more macro or meso levels). It should therefore articulate genuinely micro, meso and macro considerations. To Huamao and Fengqi [31], circular economy should be a mean to reach unification among economic, environmental and social benefits, and ultimately realize the objective of sustainable development.

Then, the European Academies Science Advisory Council (EASAC) [26] recently questioned what basic criteria should be applied in selecting indicators for monitoring the progress toward circular economy. As such, some key principles to consider were highlighted, notably: links with sustainability and industry compatibility (i.e., circular economy should harness existing sustainability-related compliance data), or communication (i.e., the effectiveness with which indicators communicate with the stakeholders). Future circularity measurement and monitoring tools should be designed and developed in software accessible to most users. For instance, Microsoft Excel could be used due to its high level of diffusion and utilization across multiple business sectors. Last but not least, in accordance with business common sense and rules of thumb, it is suitable that the framework is user-friendly, time-efficient and intelligible (easy and pleasant to use, understand and communicate) for all industrial practitioners non-expert in circular economy, and provides gateway for enhancing products and components circularity by offering a comprehensive and operational view of circularity improvement opportunities.

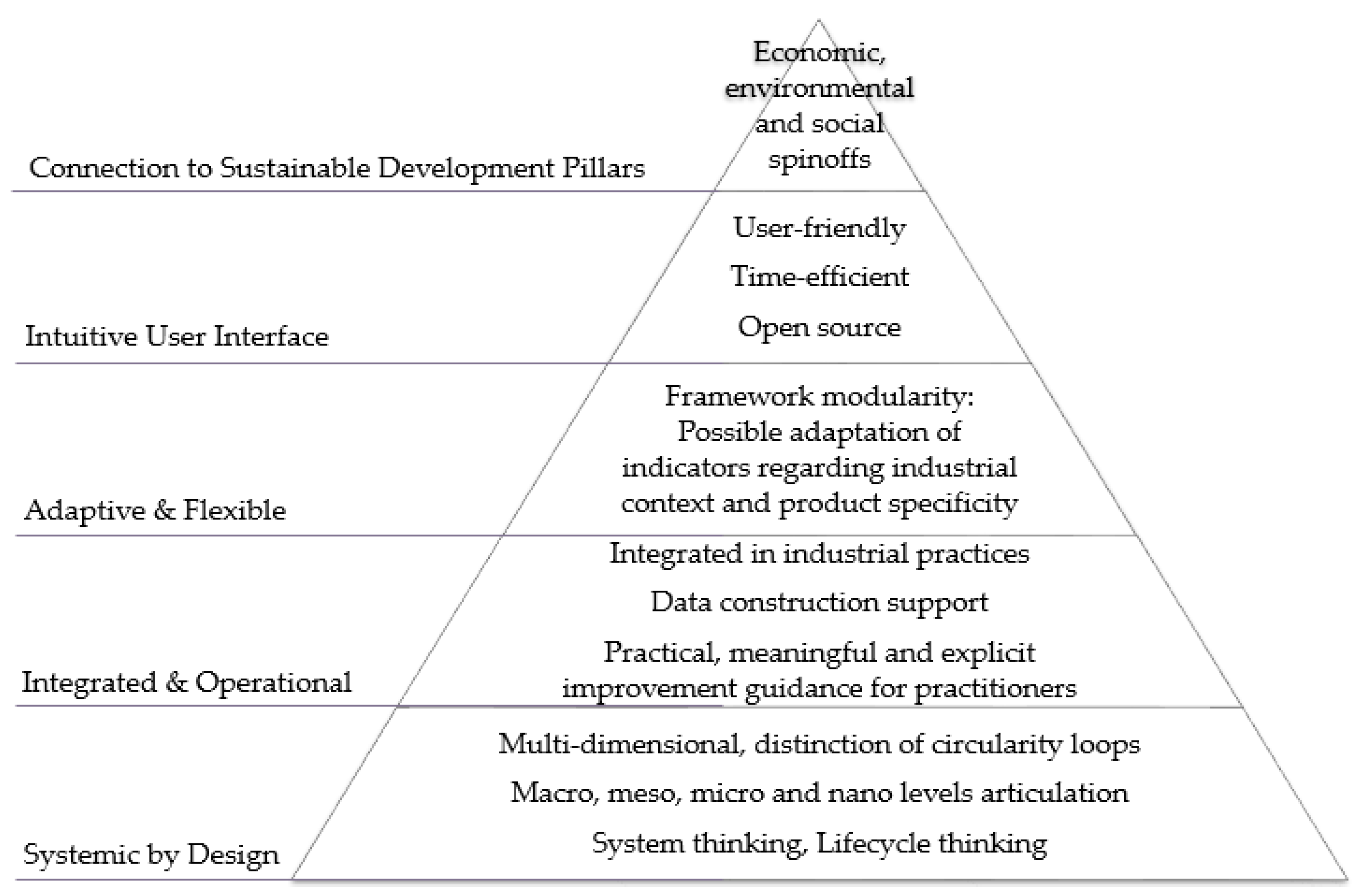

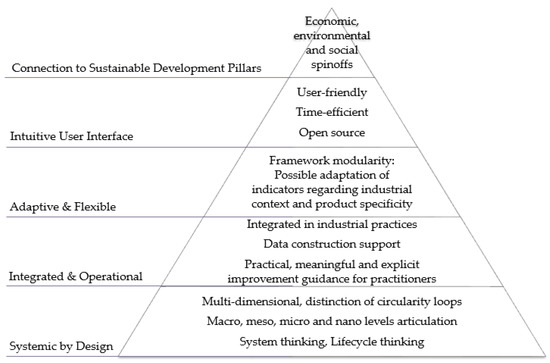

Required, desired and ideal features are synthesis and classified within a proposed hierarchy inspired by Maslow’s pyramid of needs [42] and adapted here to appropriate design of tools aiming at product performance measurement in a context of circular economy, as illustrated in Figure 2. First, the two requirements positioned at the base of the pyramid—(i) “systemic by design” and (ii) “integrated and operational”—are considered as mandatory and required features, respectively (i) to ensure a holistic approach—i.e., to consider the whole complexity of circular economy paradigm during product circularity measurement—and (ii) to be fit with industrial practices during design and development phases. Then, the two following requirements—(iii) “adaptive and flexible” and (iv) “intuitive user interface”—are seen as additional and desired features, respectively (iii) to have the ability to consider different products from diverse industrial sectors, and (iv) to be effectively and efficiently used by practitioners. Finally, the requirement placed at the top of the pyramid—(v) “connection to sustainable development pillars”—is deemed as an ultimate and ideal feature, reminding us that circular economy targets and measures should not be a goal in itself but rather a means to an end in order to achieve a more sustainable development and society [31]. Each of the five elements are elaborated in the next sub-section and practical implications are discussed to meet these requirements.

Figure 2.

Proposed hierarchy of desired features to design frameworks, methods, tools, and indicators aiming at measuring product circularity performance.

4.2. Practical Implications and Guidance for the Design of such a Framework

As aforementioned and illustrated in Figure 2, we recommend that the design and construction of an advanced framework to measure product circularity should considerer mainly five cornerstones, namely: (i) systemic by design; (ii) integrated and operational; (iii) adaptive and flexible; (iv) intuitive user interface; (v) connection with sustainable development pillars. Let us have a closed look at the consideration of each requirement to develop and implement effectively such a framework.

First, the “systemic by design” cornerstone highlights that the measurement tool should encompass a wide spectrum of the circular economy paradigm—including its complexity and principles. Such as lifecycle thinking, consideration of systemic levels and interplay between implementation levels (macro, meso, micro, and nano) are essential for an effective measure of product performance in the light of circular economy. Additionally, a multi-dimensional scoring system representing different perspectives of circular economy should be preferred, and ideally, distinction between circularity loops—in direct link with Lansink’s ladder of waste hierarchy [43,44]—should be established [45]. As there are different ways to close the loop, the overall circularity score should go further than a single and global score that encompasses and consider all different possible closed-loops at the same level without differentiation. Hence, we propose to rank these loops from circularity class A to D, which corresponds respectively from the most inner-loop to the most outer-loop of the Ellen MacArthur Foundation butterfly circular economy model [3], as illustrated in Table 2. Additionally, in Moreno et al. [46], recommendations are made to enable designers to fully consider the holistic implications for design within a circular economy, by reviewing 30 Design for X (DfX) concepts, covering thus a range of strategies that could be adopted to design and develop more circular products. Indeed, the definition of DfX methods—that are particularly fitted to the circular economy implementation—used by Moreno et al. [46] is the following: “a combination of eco-design strategies including Design for Environment and Design for Remanufacture, which leads to other design strategies such as Design for Upgrade, Design for Assembly, Design for Disassembly, Design for Modularity, Design for Maintainability”.

Table 2.

Description of the four circularity loops, according to Ellen MacArthur Foundation circular economy model [3], that should be distinguished when measuring product circularity performance.

Second, the ‘integrated and operational” cornerstone emphasizes that the framework needs to be fit with industrial practices. According to Dufrene et al. [47], integrated design is a practice to integrate different values (e.g., functions, aesthetics, manufacturability, assemblability, recyclability) of the product lifecycle in the early phases of the design process. As such, developed framework should be compatibility and complementarity with other tools and softwares used during product design and development phases, to help for instance decision-making. In addition, to be operational, as one of the main challenges to evaluate properly product circularity lies on the ability to gather adequate date, the framework should support data construction. In this light, a standardized input datasheet could be develop to facilitate the data collection, for instance divided in several sections such as technical data (e.g., bill of materials) and market or organizational data (e.g., supply chain, end-of-life pathways).

Third, the “adaptive and flexible” cornerstone underlines that the framework should be designed with a modular and non-frozen approach in order to be continuously improved through time and feedback. Indeed, in consonance with the EASAC [48]: “a circular economy needs to be flexible enough to be able to move and adapt with the quickening pace of new developments in this arena”. Among the tools reviewed, the MCI is both general enough and extendable to be applied to numerous industrial sectors and therefore to serve as a basis for developing new and advanced product circularity measurement framework specific to particular industrial sectors. As a concrete example, with the MCI tool used as a reference, Verbene [49] developed a more sophisticated method for measuring the circularity performance of a building and its associated parts.

Fourth, the “intuitive user interface” cornerstone highlights the importance of designing a proper graphical user interface (GUI) for non-expert in circular economy. In order to be time-efficient and user-friendly, the GUI should ease the acquisition of data, as well as enable a comfortable visualization of the results. Designers and developers could take inspirations from the three tools experienced in this paper. Indeed, the interfaces of the MCI [33], the CET [37] and the CEIP [20] are particularly clear, easy to use and to understand rapidly.

Fifth, the “connection to sustainable development pillars” cornerstone stresses that the actual impact of circularity should be analyzed against the sustainability performance of given a product entering in a circular economy loop. According to Geissdoerfer et al. [14] the overall benefits of circularity outweigh the drawbacks regarding impacts on sustainable development pillars, but in some cases, circularity could result to negative impacts on certain aspects of sustainability. It becomes therefore relevant to check if the potential circularity of goods—including products, components and materials—will lead to effective benefits regarding sustainability, or under which conditions and trade-offs between the three pillars. In line with ScoreLCA [50], such evaluation and consideration will enable to prioritize different types of loops in order to identify the most relevant loop for a material or product in terms of sustainability.

4.3. Positioning of the Three Tools in Regard to the Proposed Requirements

The analysis of tools’ compliance with the proposed requirements is performed in Table 3 in order to identity both best practices (+) and room for improvement (−) as an inspiration for the development of advanced frameworks aiming at assessing product circularity performance. Furthermore, such an examination provides additional insights for practitioners in the selection between these tools and their use during product design and development phases.

Table 3.

Positioning of the three tools experienced in regard to the five proposed requirements for an enhanced product circularity measurement.

In a nutshell, the MCI [33] is interesting to assess flow material potential of products circularity quickly with relatively few inputs data. Indeed, it provides a rapid overview and could be used effectively by industrial practitioners to compare products with different material combinations. The CET [37] delivers information about product circularity improvement potential at each stage of the lifecycle, but without given further practical recommendations on how to proceed to improved it. The graphical user interface of this tool is very intuitive and user-friendly even for non-circular economy experts. However, a comprehensive knowledge of the product all along lifecycle is required to answer properly the 33 questions requested. The CEIP [20] is intended for industrial practitioners and decision-makers who are looking for ease of use, simplicity and speed in the evaluation of their products’ circularity during design and development phases. Nevertheless, the access to a lot of information is required to complete the 15 input questions.

5. Conclusions—Contributions, Limitations and Call for Further Works

The use cases of product circularity performance indicators could be relevant for informative, comparative, ameliorative and communicative purposes during product design and development phases. Just to mention a few examples, they could serve as a gateway to enhance the circularity of products and associated value chains thanks to the identification of hotspots and areas for improvement, as well as to define tangible circular targets for products.

The broader impact and contribution of this work rely on the potential to foster, in an organized way, the development of new product circularity measurement frameworks intended to industrial practitioners as a support to their shift towards a more circular economy of goods. As such, analyses and proposed requirements are intended not only for managers, designers or engineers who seek to assess and improve their product circularity potential but also for researchers who are eager to develop new indicators, methods and tools aiming at measuring and enhancing product circularity. The requirements we have discussed could represent a first step to novel perspectives on product circularity measurement. In addition, knowing the different features and practical usage of each tool (e.g., insights provided, time required, level of detail, data considered in input, etc.) is crucial both to judge the operationality of each tool reviewed and to recommend most appropriate and suitable tool—or combination of tools—for industrial practitioners regarding their context, needs and constraints.

Additionally, description, test and critical analysis of each tool, performed in this article, could serve as references and guidance for industrial practitioners. In fact, some indicators and tools could be better in one situation, such as comparing rapidly the impact of two different materials on circularity performance (e.g., the Material Circularity Indicator [33]); others are more product-centric and lifecycle thinking (e.g., the Circular Economy Toolkit [37] or the Circular Economy Performance Indicator [20]). Furthermore, according to a given situation (e.g., target audience or beneficiaries, i.e., user of the tool, time available, desired level of detail, etc.) or a specific kind of product, one method could be more suitable than another one. For instance the three tools reviewed are helpful when managers need to have rapid qualitative information and overview on which areas a product could be improved to be integrated into a more circular value chain.

Although they provide a first and a rapid overview of products’ circularity, current tools neither consider the whole complexity of the circular economy paradigm, nor provide operational guidance for engineers, designers or managers to improve their products in a context of circular economy. Beyond product circularity performance measurement, methods and tools should be developed to provide companies suitable ways and mechanisms to monitor in advance the fate of their products, components, and materials. New developed tools should help businesses concretely in their move towards a more circular economy by orienting industrial practitioners to the best practices aiming at improving product circularity.

The research and analyses carried out in this paper present the three following limitations: (i) the inadequate coverage of the data availability issue; (ii) the non-consideration of biological cycle; and (iii) the absence of in-depth discussion regarding metrics and scoring systems. On the one hand, measuring potential product circularity potential during the design or redesign of a product assumes the access to a significant quantity and variety of both technical and market data. Our case study did not face this issue because a comprehensive life cycle inventory and a life cycle assessment of the catalytic converter had been performed prior. One the other hand, as the system used in the case study belonged exclusively to the technical cycle, the focus has been made on technical nutrients and their inherent cycles. Thus, the biological cycle—according to the left side of the circular economy butterfly diagram modelled by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation [3]—was out of the scope of this research work. In addition, reflection on the metrics and scoring system for measuring product circularity performance was non-comprehensively addressed in this present article. Future research discussions could include more in-depth analysis of circularity scores definitions and mathematical basis. Last but not least, considering the repercussions of the potential circularity of a given product during early design phases on the economic, environmental and social spinoffs would be an existing area for future research on the development of new frameworks aiming at assessing product circularity performance.

Even if a holistic and integrated tool to measure, improve and monitor product circularity potential performance is currently under development by the present authors, we encourage further work to contribute at providing new ways and mechanisms aiming at product performance measurement and improvement in the context of circular economy. For information, the ongoing development tool, following recommendations provided in this article, is promising in the way it claims to be both holistic and integrated. Based on the four building blocks of circular economy defined by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation [3], it will cover a wider spectrum of circular economy paradigm than the existing tools. Using a hybrid top-down (objective-driven based on circularity scores) and bottom-up (data-driven based on industrial and market fields) approach, it will ensure to be relevant and integrated to real industrial practices.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the reviewers for their highly constructive comments and suggestions in improving this article.

Author Contributions

Michael Saidani realized the literature review, experiments and analyses. Michael Saidani conceptualized and wrote the manuscript. Bernard Yannou, Yann Leroy and François Cluzel have taken part in conceptualizing the research work, reviewing and checking the paper structure and content.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF). Schools of Thought. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/circular-economy/schools-of-thought (accessed on 1 February 2017).

- Sauvé, S.; Bernard, S.; Sloan, P. Environmental sciences, sustainable development and circular economy: Alternative concepts for trans-disciplinary research. Environ. Dev. 2016, 17, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF). Towards the Circular Economy—Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition; Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Cowes, UK, 2013; Chapter 3. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission (EC). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: Towards a Circular Economy: A Zero Waste Programme for Europe. COM (2014) 0398; European Commission (EC): Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission (EC). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: Closing the Loop—An EU Action Plan for the Circular Economy. COM (2015) 614/2; European Commission (EC): Brussels, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Accenture Strategy. Gaining an Edge: Growth, Innovation and Customer Value from the Circular Economy. Available online: https://www.accenture.com/us-en/insight-circular-economy-gaining-edge (accessed on 1 March 2017).

- McKinsey Global Institute (MGI). Europe’s Circular Economy Opportunity. Available online: http://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/sustainability-and-resource-productivity/our-insights/europes-circular-economy-opportunity (accessed on 1 March 2017).

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF). Partners. Available online: http://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/about/partners (accessed on 1 February 2017).

- Parmenter, D. Key Performance Indicators: Developing, Implementing, and Using Winning KPIs; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; p. 448. [Google Scholar]

- Circle Economy. Circularity Assessment for Organisations: Draft Indicators v. 0.2; Circle Economy: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; p. 23. [Google Scholar]

- Circle Economy. Circle Assessment Tool—Measuring Circularity and Identifying Opportunities to Adapt Circular Strategies. Available online: http://www.circle-economy.com/tool/circleassessment/ (accessed on 1 February 2017).

- Kingfisher. The Business Opportunity of Closed Loop Innovation; Closed Loop Innovation Booklet; Kingfisher: Westminster, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fink, A. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From Paper to the Internet; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Savaget, P.; Bocken, N.M.P.; Hultink, E.J. The Circular Economy—A new sustainability paradigm? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carencotte, F.; Geldron, A.; Villeneuve, J.; Gaboriau, H. Economie circulaire et recyclage des métaux. Geosciences 2012, 15, 64–71. [Google Scholar]

- CIRAIG. Circular Economy: A Critical Literature Review of Concepts; Bibliothèque et Archives Nationales du Québec (BAnQ): Quebec City, QC, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Balanay, R.; Halog, A. Charting Policy Directions for Mining’s Sustainability with Circular Economy. Recycling 2016, 2, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieder, M.; Rashid, A. Towards circular economy implementation: A comprehensive review in context of manufacturing industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 115, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Fu, J.; Sarkis, J.; Xue, B. Towards a national circular economy indicator system in China: An evaluation and critical analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 23, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, P.; Cayzer, S. Design of indicators for measuring product performance in the circular economy. In 3rd International Conference on Sustainable Design and Manufacturing, SDM 2016; Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2016; pp. 307–321. [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey, L.; Todd, C. Defining thresholds for freshwater sustainability indicators within the context of South African water resource management. In Proceedings of the 2nd WARFA/Waternet symposium, Cape Town, South Africa, 30–31 October 2001.

- Church, C.; Rogers, M. Designing for Results: Integrating Monitoring and Evaluation in Conflict Transformation Programs; Search for Common Ground: Washington, DC, USA, 2006; p. 228. [Google Scholar]

- Arnsperger, C.; Bourg, D. Vers une économie authentiquement circulaire: Réflexions sur les fondements d’un indicateur de circularité. Revue de l’OFCE 2016, 145, 91–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabaghi, M.; Mascle, C.; Baptiste, P.; Rostamzadeh, R. Sustainability assessment using fuzzy-inference technique (SAFT): A methodology toward green products. Expert Syst. Appl. 2016, 56, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banaité, D. Towards Circular Economy: Analysis of Indicators in the Context of Sustainable Development. In International Scientific Conference for Young Researchers, Social Transformations in Contemporary Society; Mykolas Romeris University: Vilnius, Lithuania, 2–3 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- European Academies Science Advisory Council (EASAC). Indicators for a Circular Economy; EASAC Policy Report 30; European Academies Science Advisory Council (EASAC): Halle, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ghisellini, P.; Cialani, C.; Ulgiati, S. A review on circular economy: The expected transition to a balanced interplay of environmental and economic systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 114, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waste & Resources Action Programme. WRAP’s Vision for the UK Circular Economy to 2020. Available online: http://www.wrap.org.uk/content/wraps-vision-uk-circular-economy-2020 (accessed on 1 February 2017).

- Zhou, Z.; Chen, X.; Xiao, X. On Evaluation Model of Circular Economy for Iron and Steel Enterprise Based on Support Vector Machines with Heuristic Algorithm for Tuning Hyper-parameters. Appl. Math. Inf. Sci. 2013, 6, 2215–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S. The Research on Quantitative Evaluation of Circular Economy Based on Waste Input-Output Analysis. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2012, 12, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huamao, X.; Fengqi, W. Circular Economy Development Mode Based on System Theory. Chin. J. Popul. Res. Environ. 2007, 5, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency (EEA). More from Less—Material Resource Efficiency in Europe; European Environment Agency (EEA): Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016; p. 151. [Google Scholar]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF). Circularity Indicators—An Approach to Measure Circularity. Methodology & Project Overview; Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF): Cowes, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Giurco, D.; Littleboy, A.; Boyle, T.; Fyfe, J.; White, S. Circular economy: Questions for responsible minerals, additive manufacturing and recycling of metals. Resources 2014, 3, 432–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin-Johnson, E.; Figge, F.; Canning, L. Resource duration as a managerial indicator for Circular Economy performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 133, 589–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaya, J. Assessment of the Environmental Benefits Provided by Closed-Loop Strategies for Industrial Products. Ph.D. Thesis, University Grenoble Alpes, Grenoble, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, J.; Bocken, N. The Circular Economy Toolkit. Available online: http://circulareconomytoolkit.org/ (accessed on 1 February 2017).

- Hagelüken, C.; Lee-Shin, J.U.; Carpentier, A.; Heron, C. The EU Circular Economy and Its Relevance to Metal Recycling. Recycling 2016, 1, 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidani, M.; Cluzel, F.; Leroy, Y.; Auclaire, A. Time-efficient eco-innovation workshop process in complex system industries. In Proceedings of the 14th International Design Conference, Dubrovnik, Croatia, 16–19 May 2016.

- Halog, A.; Manik, Y. Advancing Integrated Systems Modelling Framework for Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment. Sustainability 2011, 3, 469–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleischwitz, R.; Wilts, H. An international metal covenant: A step towards global sustainable resource management. In Factor X: Re-Source—Designing the Recycling Society; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 87–98. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow, A. A Theory of Human Motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1943, 50, 370–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parto, S.; Loorbach, D.; Lansink, A. Transitions and institutional change: The case of the Dutch waste subsystem. In Industrial Innovation and Environmental Regulation; United Nations University Press: Tokyo, Japan, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Recycling. Available online: http://www.recycling.com/downloads/waste-hierarchy-lansinks-ladder/ (accessed on 1 February 2017).

- Wilts, H.; Von Gries, N.; Bahn-Walkowiak, B. From Waste Management to Resource Efficiency—The Need for Policy Mixes. Sustainability 2016, 8, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, M.; de los Rios, C.; Rowe, Z.; Charnley, F. A Conceptual Framework for Circular Design. Sustainability 2016, 8, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufrene, M.; Zwolinski, P.; Brissaud, D. An engineering platform to support a practical integrated eco-design methodology. CIRP Ann. Manuf. Technol. 2013, 62, 131–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Academies Science Advisory Council (EASAC). Circular Economy: A Commentary from the Perspectives of the Natural and Social Sciences; European Academies Science Advisory Council: Halle, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jeroen, V. Building Circularity Indicators—An Approach for Measuring Circularity of a Building. Master’s Thesis, Eindhoven University of Technology, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- ScoreLCA. Circular Economy: Concepts and Evaluation Methods; ScoreLCA: Villeurbanne, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).