Assessment of the Impact of the Revised National E-Waste Framework on the Informal E-Waste Sector of Nigeria

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What are the key hotspots in the E-Waste value chain network in Lagos, Nigeria, and how do they contribute to E-Waste mass flow?

- What roles do informal operators play within the E-Waste flow network, and how do their activities shape the sector?

- What are the economic and environmental impacts of activities at the identified hotspots, and how can these be assessed both quantitatively and qualitatively?

- What reorganizational options are available to ensure the environmentally sound management (ESM) of E-Waste in Nigeria?

EE Regulation (2022) and Recent Developments

- An amendment of the 2011 National EE Regulation with defined roles for stakeholders and implementation of mandated EPR.

- Development of the Black Box software, on Microsoft Azure version 1, which is a registry through which the market shares of producers are determined to enable EPRON to collect EPR levies. The levies are used to support recyclers and collectors, raise awareness, conduct research, establish standards, and EPRON administrative duties and research. The BlackBox is expected to provide a comprehensive database of producers and importers, for the management of producers’ market share data and the calculation of EPR fees for different product categories [19].

- Development of a Guidance Document for EPR implementation [20] with technical support from UNEP and international stakeholders. The Guidance Document defined the roles and responsibilities of different stakeholders and set time-bound targets for the effective implementation of the EPR scheme in Nigeria.

- Initiated a pilot E-Waste collection that constituted the first national E-Waste collection and recycling target. The E-Waste collecting and recycling pilots are in line with the new requirements of the Guidance for EPR implementation, to understand the local treatment cost for different EEE categories covered by the EPR system.

2. Results and Discussions

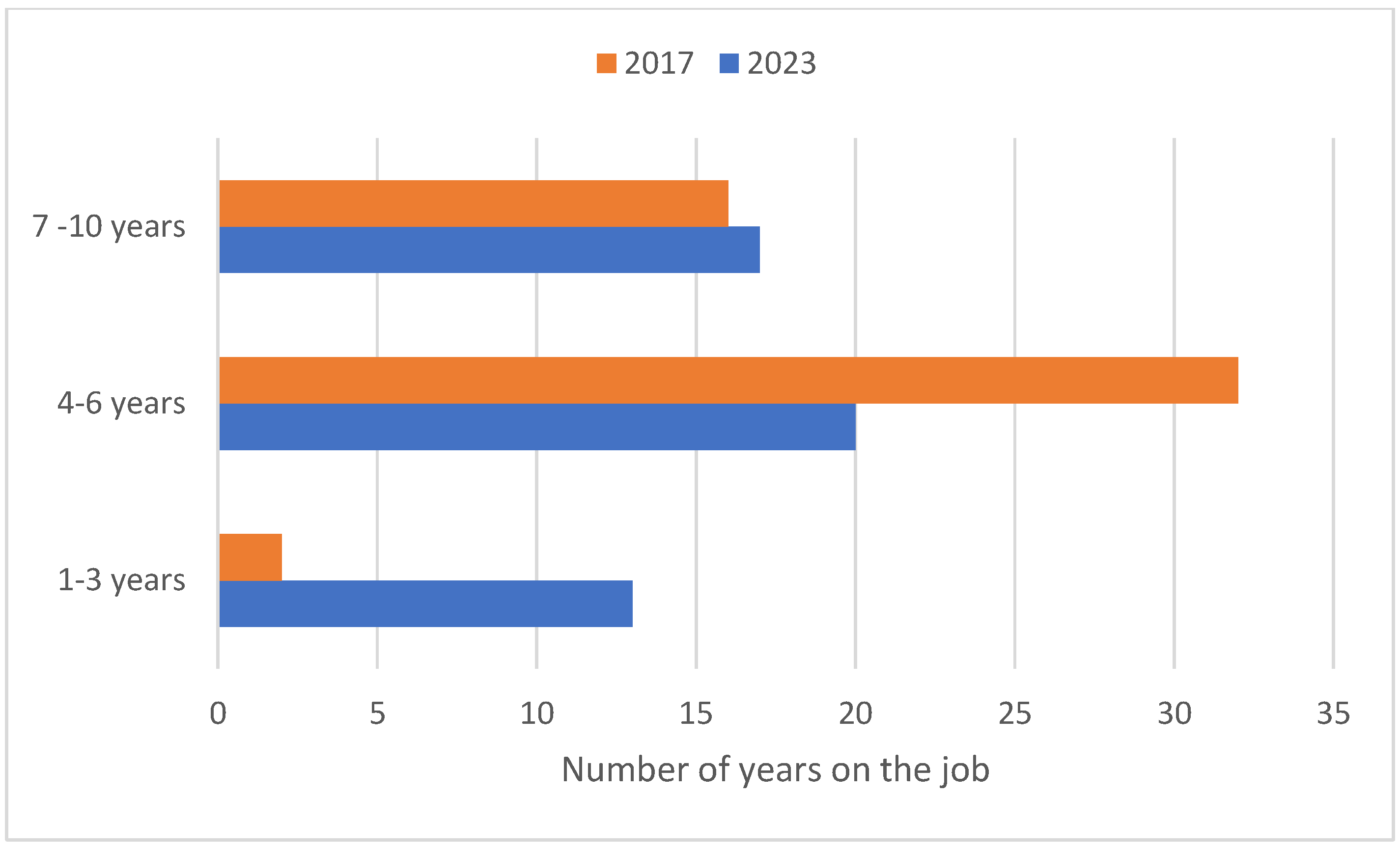

2.1. Demography

2.2. Operations of the Informal Collectors

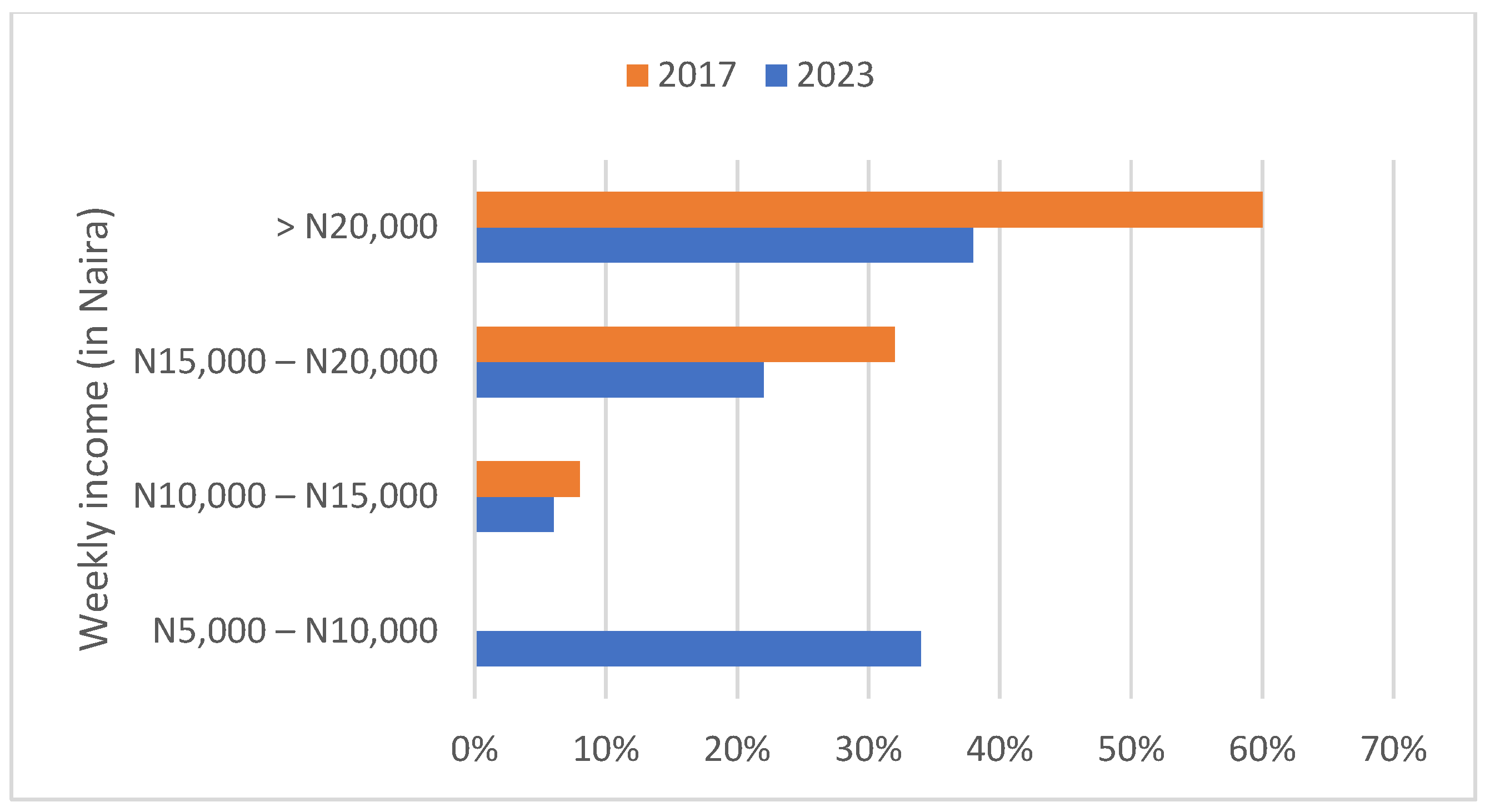

2.3. Economic Aspects

- (i)

- type of device: computers and mobile phones attract more value compared to other devices,

- (ii)

- condition of device: this depends on the functionality of the device or components thereof. Functional and repairable devices are repaired and sold, or the components are reused as replacement parts. This attracts a higher profit margin,

- (iii)

- the number of valuable materials present: printed wiring boards (PWBs) of mobile phones and computers are of more value when compared to those of radios and other electronics.

| E-Waste Fraction | Price in € (per kg/Unit) * | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost of Acquisition | Cost After Dismantling | Retail Price | Profit | |

| Cable | 0.57 | 0.60 | 0.95 | 0.35 |

| Aluminum | 0.71 | 0.86 | 1.0 | 0.14 |

| Copper | 2.86 | 3.71 | 4.50 | 0.79 |

| Steel | 0.85 | 1.00 | 1.20 | 0.20 |

| PWB | 14.28 | 15.00 | 16.00 | 1.00 |

| Plastic ** | 0.42 | 0.50 | 0.65 | 0.15 |

2.4. Health Safety and the Environment

2.5. Stakeholders Compliance with 2011 Regulations

2.6. Reorganizing the Current E-Waste System

2.7. Policy Gaps and Challenges in Nigeria’s E-Waste Regulation

- Institutional Weakness and Fragmentation: The NESREA’s enforcement capacity remains inadequate. Regulatory overlaps and insufficient funding hinder monitoring and compliance.

- Weak Economic Incentives: Recyclers and collectors lack financial motivation to participate in formal take-back systems. As demonstrated in Ghana [28], economic incentives are crucial for behavioral change.

- I.

- Localized EPR Implementation: Policies must reflect Nigeria’s socio-economic realities. As Inverardi-Ferri [29] argues, policy mobility often results in failures when neoliberal frameworks are imposed without local adaptation. Nigeria’s EPR scheme should incorporate flexible compliance pathways and recognize informal actors as primary stakeholders.

- II.

- Economic Incentives and Conditional Integration: Drawing on Ghana’s and Sri Lanka’s experiments, as presented in [30], collectors could be paid bonuses for materials delivered to certified recyclers. Microcredit, tax breaks, and cooperative grants would help transition collectors toward safer practices.

- III.

- Cooperative Based Formalization: It is essential to encourage cluster-based cooperatives, as used in South Africa [19], to organize informal collectors. Provide training, health insurance, and shared facilities to improve occupational safety and legal compliance.

- IV.

- Phased Enforcement and Monitoring: The NESREA should implement a phased enforcement plan targeting high volume E-Waste zone with stricter monitoring. Digital tracking systems via EPRON’s Black Box can support real-time compliance checks and identify potential perpetrators.

- V.

- Gender-Inclusive Policy Measures: Building on Balde et al. [5], policies must address gender-based disparities by offering women better access to training, tools, and leadership roles in recycling cooperatives.

- VI.

- Cross-Border E-Waste Controls: Cameroon’s “Guichet Unique” provides a replicable model to screen imports and reduce illegal E-Waste shipments [19]. Nigeria must strengthen port inspections and require standardized documentation for all used EEE imports.

- i.

- Financial dependency: Inability to fund their operations restricts the scavengers/informal operators. Therefore, collectors and processors are not sufficiently free to direct materials as they wish. Funding would free the informal operators to change the flow of their collected E-Waste route for better financial gains.

- ii.

- Loyalty and dependency: Most scavengers/dismantlers are migrant workers. Intermediaries or their agents bring them from rural areas and engage them in the cities. They also provide accommodation and support with daily living until they are integrated into city life. This makes the informal workers completely dependent on the agents funding their operations. Loyalty makes the operators give the materials collected to agents rather than to the formal recyclers, even if they offer to pay more.

- iii.

- Weak regulation, enforcement, and monitoring of the sector: An unregulated informal sector with very lax enforcement of existing regulation invariably allows the informal operators freedom to engage in activities that expose man and the environment to a cocktail of toxins. Furthermore, compromising of regulators is one of the key factor that hampers these efforts. A regulated sector would allow the formulation of laws, which when enforced and monitored, could result in grave consequences for offenders and the risk of fines.

- i.

- Slowly linking the informal activities to the formal sector might be an initial option for those fractions that are hazardous, which would allow the collectors to continue their operations, while ensuring that they hand over hazardous material to a proper treatment operator. This would bring the informal operators closer to the official system and make it easier to engage them and improve their situation step by step, which could, in the end mean, integration into the formal sector.

- ii.

- Integrating the activities of the informal operators into that of formal stakeholders in the E-Waste management sector. To effectively integrate informal operators into Nigeria’s formal E-Waste sector, a structured, incentive-driven approach is needed. Since informal processors dominate E-Waste collection and pre-processing, they should be engaged as primary collectors and dismantlers, with restrictions on hazardous activities like CRT breaking and open burning. Practical steps include issuing collector identification cards, establishing designated drop-off points, and providing buy-back schemes where formal recyclers purchase pre-processed materials at fair prices. Training programs on safe dismantling techniques, supported by microfinance schemes, could help informal workers transition into safer, income-generating roles. Partnerships between government agencies, industry players, and cooperatives could create hybrid recycling hubs, where informal workers are integrated into the formal processing chain. To ensure compliance, enforcement should combine incentives (such as tax breaks or equipment grants) with strict penalties for environmental violations. A phased approach, starting with major E-Waste hotspots, would allow for adjustments based on local realities, ensuring a scalable, sustainable transition that benefits workers, businesses, and the environment.

- iii.

- Some of the collectors receive daily loans, often from the treatment operators or scrap dealers, which they payback. Supporting the informal operators with a living wage and other incentives (based on the type and quantities of fraction collected) would enable them to hand over materials to formal processors. This could be funded through the EPR via the formal operators or other transfer channels.

- iv.

- Establishing a financing mechanism by exploring the strength of the current EPR system through monitoring and enforcement. Data collection and storage are also key for ensuring the success of the system. The recording and development of a database on volumes of imports is important for the development of a financial system for the EPR. This automatically makes importers an especially important stakeholder in the EPR system. A review of the existing policy guidance on EEE and the introduction of an Environmental Health Standard (EHS) would ensure ESM.

- v.

- The review of the legislation banning the importation of E-Waste and its enforcement is crucial in controlling the illegal importation of E-Waste.

- vi.

- Continuous education and enlightenment of the informal operators should be incorporated into the activities of the regulatory agencies and other stakeholders.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Tools

3.2. Study Area and Approach

4. Limitations and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Forti, V.; Baldé, C.P.; Kuehr, R.; Bel, G.; The Global E-Waste Monitor 2020: Quantities, Flows, and the Circular Economy Potential. United Nations University (UNU)/United Nations Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR)—Co-Hosted by the SCYCLE Programme. 2020. Available online: https://collections.unu.edu/view/UNU:7737 (accessed on 21 March 2024).

- Nnorom, I.C.; Odeyingbo, O. Electronic waste management practices in Nigeria. In Handbook of Electronic Waste Management: International Best Practices and Case Studies; Prasad, M.N.V., Vithanage, M., Borthakur, A., Eds.; Chapter 14; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 323–354. ISBN 978-0-12-817030-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oke, E.A.; Potgieter, H. Discarded E-Waste/printed circuit boards: A review of their recent methods of disassembly, sorting, and environmental implications. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2024, 26, 1277–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.; Xu, X.; Eskenazi, B.; Asante, K.; Chen, A.; Fobil, J.; Bergman, A.; Brennan, L.; Sly, P.; Nnorom, I.C.; et al. Severe dioxin-like compound (DLC) contamination in E-Waste recycling areas: An under-recognized threat to local health. Environ. Int. 2020, 139, 105731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldé, C.P.; Kuehr, R.; Yamamoto, T.; McDonald, R.; D’Angelo, E.; Althaf, S.; Bel, G.; Deubzer, O.; Fernandez-Cubillo, E.; Forti, V.; et al. Global E-Waste Monitor 2024. United Nations Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR) Sustainable Cycles (SCYCLE) Programme Bonn Germany, International Telecommunication Union (ITU) Switzerland, Fondation Carmignac, France. 2024. Available online: https://ewastemonitor.info/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/GEM_2024_18-03_web_page_per_page_web.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- McAllister, L.; Magee, A.; Hale, B. Women, E-Waste, and technological solutions to climate change. Health Hum. Rts. J. 2014, 16, 166. [Google Scholar]

- Njoku, A.; Agbalenyo, M.; Laude, J.; Ajibola, T.F.; Attah, M.A.; Sarko, S.B. Environmental injustice and electronic waste in Ghana: Challenges and recommendations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 21, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andeobu, L.; Wibowo, S.; Grandhi, S. Informal E-Waste recycling practices and environmental pollution in Africa: What is the way forward? Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2023, 252, 114192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, J.K.; Kumar, S. Informal E-Waste recycling: Environmental risk assessment of heavy metal contamination in Mandoli industrial area, Delhi, India. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2014, 21, 7913–7928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchert, M.; Manhart, A.; Mehlhart, G.; Degreif, S.; Bleher, D.; Schleicher, T.; Meskers, C.; Picard, M.; Weber, F.; Walgenbach, S.; et al. Transition to Sound Recycling of E-Waste and Car Waste in Developing Countries—Lessons Learned from Implementing the Best-of-Two-Worlds Concept in Ghana and Egypt. Freiburg. 2016. Available online: https://www.oeko.de/oekodoc/2533/2016-060-en.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- Owusu-Sekyere, K.; Batteiger, A. Improving the E-Waste Management Conditions in Agbogbloshie through a Material Flow Analysis. In Proceedings of the DGAW Congress, Vienna, Austria, 15–16 March 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Osibanjo, O.; Nnorom, I.C. The challenge of electronic waste (E-Waste) management in developing countries. Waste Manag. Res. 2007, 25, 489–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borthakur, A. Generation and management of electronic waste in India: An assessment from stakeholders’ perspective. J. Dev. Soc. 2015, 31, 220–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohajinwa, C.M.; Van Bodegom, P.M.; Xie, Q.; Chen, J.; Vijver, M.G.; Osibanjo, O.O.; Peijnenburg, W.J. Hydrophobic organic pollutants in soils and dusts at electronic waste recycling sites: Occurrence and impacts of polybrominated diphenyl ethers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Children and Digital Dumpsites: E-Waste Exposure and Child Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240023901 (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Odeyingbo, O.; Nnorom, I.; Deubzer, O. Person in the Port Project: Assessing Import of Used Electrical and Electronic Equipment into Nigeria. UNU-ViE SCYCLE and BCCC Africa. 2017. Available online: http://collections.unu.edu/eserv/UNU:6349/PiP_Report.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Odeyingbo, A.O.; Nnorom, I.C.; Deubzer, O.K. Used, and waste electronics flows into Nigeria: Assessment of the quantities, types, sources, and functionality status. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 666, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, K.; Uchendu, C.; Fitzpatrick, C. Quantifying used electrical and electronic equipment exported from Ireland to west Africa in roll-on roll-off vehicles. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 164, 105177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Telecommunication Union (ITU), 2022. Global and Complementary Actions for Electronics Extended Producer Responsibility. A Thought Paper for International E-Waste Day 2022. ITU/WEEE Forum/StEP. Global and Complementary Actions for Electronics Extended Producer Responsibility—ITU Hub. Available online: https://www.step-initiative.org/files/_documents/publications/Global%20and%20complementary%20actions%20for%20electronics%20extended%20producer%20responsibility_final.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2024).

- National Environmental Standards and Regulations Enforcement Agency (NESREA) (n.d). Guidance Document for the Implementation of the Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) Programmer for the Electrical/Electronics Sector in Line with Circular Economy. Available online: https://www.nesrea.gov.ng/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Finalized_EPR_Guidance_Document.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2024).

- National Environmental Standards and Regulations Enforcement Agency (NESREA). National Environmental Electrical/Electronic Regulation 2022. The Federal Republic of Nigeria Official Gazette S.I. No 79, 2022. Available online: https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/nig225823.pdf (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Ohajinwa, C.M.; Van Bodegom, P.M.; Vijver, M.G.; Peijnenburg, W.J. Health risks awareness of electronic waste workers in the informal sector in Nigeria. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohajinwa, C.M.; Van Bodegom, P.M.; Vijver, M.G.; Peijnenburg, W.J. Impact of informal electronic waste recycling on metal concentrations in soils and dusts. Environ. Res. 2018, 164, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UN Environment Programme (UNEP). Nigeria Turns the Tide on Electronic Waste. 2019. Available online: https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/press-release/nigeria-turns-tide-electronic-waste (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- National Environmental Standards and Regulations Enforcement Agency (NESREA). The National Environmental (Electrical Electronic Sector) Regulations. 2011. Available online: https://leap.unep.org/en/countries/ng/national-legislation/national-environmental-electricelectronic-sector-regulations-2011 (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Nigeria Acts to Fight Growing E-Waste Epidemic. UNEP. 2023. Available online: https://www.unep.org/gef/news-and-stories/press-release/nigeria-acts-fight-growing-E-Waste-epidemic (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- Government of Nigeria. The Federal Republic of Nigeria Official Gazette No 50, Vol. 98, S.I 23. National Environmental (Electrical/Electronic Sector) Regulations. 2011. Available online: https://archive.gazettes.africa/archive/ng/2011/ng-government-gazette-dated-2011-05-25-no-50.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH. 2020 Incentive Based Collection of E-Waste in Ghana. Available online: https://www.giz.de/en/downloads/giz2020_en_incentive_based_collection_e_waste%20_ghana.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Inverardi-Ferri, C. Variegated geographies of electronic waste: Policy mobility, heterogeneity, and neoliberalism. Area Dev. Policy 2017, 2, 314–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranasinghe, W.W.; Athapattu, B.L. Challenges in E-Waste management in Sri Lanka Chapter 13. In Handbook of Electronic Waste Management International Best Practices and Case Studies; Prasad, M.N.V., Vithanage, M., Borthakur, A., Eds.; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 283–322. ISBN 978-0-12-817030-4. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, J.M.; Garb, Y. Polluted Politics; Cambridge Books: Cambridge, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz, Y.; Lora-Wainwright, A. In the name of circularity: Environmental improvement and business slowdown in a Chinese recycling hub. Worldw. Waste 2019, 2, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 23 November 2022).

- Agamuthu, P.; Khidzir, K.; Fauziah, S.H. Drivers of sustainable waste management in Asia. Waste Manag. Res. 2009, 27, 625–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH. Assessing the Role and Impact of EPR in the Prevention of Marine Plastic Packaging Litter. 2022. Available online: http://www.giz.de/en/worldwide/93799.html (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- Tirado-Soto, M.M.; Zamberlan, F.L. Networks of recyclable material waste-picker’s cooperatives: An alternative for the solid waste management in the city of Rio de Janeiro. Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 1004–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demaria, F.; Schindler, S. Contesting urban metabolism: Struggles over waste-to-energy in Delhi, India. Antipode 2016, 48, 293–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbah, P.O.; Nzeadibe, T.C. Inclusive municipal solid waste management policy in Nigeria: Engaging the informal economy in post-2015 development agenda. Local Environ. 2017, 22, 203–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oke, E.A.; Potgieter, H. Recent chemical methods for metals recovery from printed circuit boards: A review. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2024, 26, 1349–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, B.; Cardon, P.; Poddar, A.; Fontenot, R. Does Sample Size Matter in Qualitative Research? A Review of Qualitative Interviews in IS Research. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2013, 54, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, O.C. Sampling in interview-based qualitative research: A theoretical and practical guide. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2014, 11, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, E.A.; Akormedi, M.; Asampong, E.; Meyer, C.G.; Fobil, J.N. Informal processing of electronic waste at Agbogbloshie, Ghana: Workers’ knowledge about associated health hazards and alternative livelihoods. Glob. Health Promot. 2017, 24, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, R.R.; Pathak, P. Policy issues for efficient management of E-Waste in developing countries Chapter 4. In Handbook of Electronic Waste Management; International Best Practices and Case Studies; Prasad, M.N.V., Vithanage, M., Borthakur, A., Eds.; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 81–99. ISBN 978-0-12-817030-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Hotspot | Prevailing Activities | Implications | Environmental Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Unregulated importation of UEEE mixed with E-Waste and household items |

| Transboundary movements of waste (refer to the shipment of waste across country borders, often for recycling, treatment, or disposal. It is a key issue in global environmental law, especially when wealthy countries export waste to poorer ones). The imported E-Waste is not reused and only worsens the already severe socio-environmental situation. |

| 2 | Material recovery from E-Waste without PPE (e.g., breaking CRT that contain substantial amounts of lead estimate at 1–4 kg Pb/CRT) |

| Emission of dust and fumes containing metals (e.g., Pb, Cd, etc.) and organic compounds (e.g., PBDEs). |

| 3 | Open burning of cables and printed wiring board (PWB), as well as waste plastic housing units |

| Same as above. |

| 4 | Unregulated dumping of hazardous non-valuable components and residues. Flammable components burnt. |

| Environmental contamination and human exposure to toxins. |

| Regulatory Aspect | Provisions in Nigeria EEE Regulation, 2011 | Observation During Assessment Work |

|---|---|---|

| Guide for producers and importers of UEEE. |

| 97% of UEEE importers not registered |

| 26% of imported UEEE are non-functional | |

| Evidence of importation of E-Waste observed | |

| None was returned during the study period | |

| Only a few have been reported in the past, with none during the study period | |

| Activities that require registration and permits under the regulation: |

| Observed in less than 1% |

| Only a few importers are registered | |

| Only 4% observed | |

| Specific provisions of the EEE sector regulations |

| Importing is still very evident |

| Not yet in existence. This is crucial to the sustainable management of E-Waste | |

| Non-existent now | |

| Low compliance |

| Funding Mechanism for E-Waste Management According to the Revised Nigeria EEE Regulation, 2022 | Summary of Key Components of Operational Guide (Manual) for E-Waste Collectors in the EPRON Manual (2023) |

|---|---|

The mandatory EPR requirement on stakeholders (producers, marketers, collectors, consumers etc.):

| EPRON WEEE SMART manual provides the specifications:

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Odeyingbo, O.A.; Deubzer, O.K.; Ogunmokun, O.A. Assessment of the Impact of the Revised National E-Waste Framework on the Informal E-Waste Sector of Nigeria. Recycling 2025, 10, 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/recycling10030117

Odeyingbo OA, Deubzer OK, Ogunmokun OA. Assessment of the Impact of the Revised National E-Waste Framework on the Informal E-Waste Sector of Nigeria. Recycling. 2025; 10(3):117. https://doi.org/10.3390/recycling10030117

Chicago/Turabian StyleOdeyingbo, Olusegun A., Otmar K. Deubzer, and Oluwatobi A. Ogunmokun. 2025. "Assessment of the Impact of the Revised National E-Waste Framework on the Informal E-Waste Sector of Nigeria" Recycling 10, no. 3: 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/recycling10030117

APA StyleOdeyingbo, O. A., Deubzer, O. K., & Ogunmokun, O. A. (2025). Assessment of the Impact of the Revised National E-Waste Framework on the Informal E-Waste Sector of Nigeria. Recycling, 10(3), 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/recycling10030117