1. Introduction

Lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) have become the dominant energy storage technology for electric vehicles and renewable energy integration due to their high energy density, low self-discharge rate, fast response, and long cycle life [

1,

2]. Their widespread deployment—from consumer electronics to grid-scale storage—has driven rapid market growth, with global EV-related LIB demand reaching 142.8 GWh in 2020 and projected to exceed 91.8 billion USD in the coming years [

3]. However, like many electrochemical systems, LIBs inevitably suffer performance degradation, or aging, over time. This aging process, characterized by capacity fade and increased internal resistance, is a primary factor leading to inaccurate state estimation in practical applications. Improper operation, such as overcharging, deep discharging, or high C-rate cycling, accelerates irreversible wear of electrodes and separators, leading to further degradation and heightened safety risks [

4].

Ensuring safe and efficient operation therefore requires accurate real-time estimation of internal states—most notably the state of charge (SOC) and state of health (SOH)—which are pivotal for battery management systems (BMSs) [

5]. SOC, representing the ratio of remaining charge to nominal capacity, directly affects driving range estimation, energy efficiency, and charge/discharge control strategies [

6]. SOH, reflecting the degradation level and residual lifetime, underpins maintenance scheduling and end-of-life prediction. Both states cannot be measured directly during regular operation and must be inferred from measurable electrical, thermal, or mechanical indicators. The challenge lies in maintaining estimation accuracy under diverse operating conditions, where sensor noise, parameter drift, and nonlinear battery dynamics intensify the difficulty of reliable state tracking [

7].

SOC estimation methods fall into three categories: physics-based, data-driven, and hybrid. Physics-based approaches—such as Coulomb counting and open-circuit voltage (OCV) methods, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy—offer mechanistic rigor but are often computationally intensive, less adaptive, or require rest periods for OCV calibration [

8,

9,

10]. In practice, Ah-integration with periodic OCV correction remains common due to simplicity [

11] but is sensitive to initial SOC errors and sensor drift, leading to cumulative inaccuracies [

12].

Data-driven methods model the battery as a nonlinear black-box system, learning mappings from measurable signals—such as current, voltage, and temperature—to SOC without explicitly describing internal electrochemical processes [

13]. Leveraging large-scale telemetry from BMS sensors, machine learning approaches have demonstrated strong capability in reconstructing the complex multi-variable relationship governing SOC under diverse load profiles and environments [

14]. Recurrent neural networks, particularly Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) architectures, effectively capture the temporal dependencies inherent in charging/discharging cycles [

15], and recent adaptive designs improve robustness under temperature variations [

16,

17]. Recent advances in deep learning have also explored transfer learning for battery modeling under extreme conditions. For instance, Shi et al. [

18] applied transfer learning to predict heat release during thermal runaway, demonstrating the potential of knowledge transfer across battery operating regimes. Such frameworks have also been extended to state of health estimation [

19]. Nevertheless, purely data-driven models remain challenged by limited physical interpretability and potential performance degradation when operating under extreme temperatures, fast transients, or battery aging [

20,

21].

Hybrid approaches integrate physical priors with data-driven flexibility, enhancing generalization while retaining interpretability [

22,

23]. Examples include Bayesian electrochemical model hybrids [

24], ANFIS with real-time correction [

25], and neural network Kalman filter (NN-KF) designs [

26,

27]. However, most hybrids achieve only shallow coupling—such as parameter adaptation or post hoc correction—rather than end-to-end co-optimization of physics and temporal learning. Balancing high model fidelity with computational efficiency remains challenging, especially for real-time BMSs [

28,

29,

30]. Robustness under extreme conditions (low temperature, high C-rate charging, long-term aging) is also difficult due to amplified model uncertainty and sensor noise [

31].

Python 3.10 battery mathematical modeling (PyBaMM) (e.g., Version: 25.10.2) is an open-source, community-driven platform for high-fidelity electrochemical modeling, designed to facilitate collaboration and accelerate battery research by applying modern software engineering practices [

32]. By representing models as expression trees and processing them through a modular pipeline, PyBaMM enables flexible implementation and comparison of battery models and numerical methods, solving multi-scale partial differential equations to capture spatially resolved internal states such as lithium concentration, potential distribution, and temperature effects [

33]. These capabilities make PyBaMM well-suited for studying degradation mechanisms and state estimation problems; however, direct deployment of full-fidelity models for real-time SOC estimation in battery management systems is hindered by high computational costs and sensitivity to parameter identification errors under dynamic conditions [

34]. While methods such as signal decoupling and Monte Carlo dropout [

35] have been explored to improve generalization, they do not inherently enforce physical plausibility—motivating hybrid approaches that integrate PyBaMM’s physical rigor into data-driven architectures to achieve both interpretability and efficiency.

To address these gaps, we propose a Physics-Informed Transformer (PI-Transformer) enabling deep, differentiable integration of electrochemical constraints within a Transformer architecture. Our key insight is that the core electrochemical principles encoded in PyBaMM, such as the differential equation governing SOC change (

), can be extracted and embedded directly into a deep learning architecture as differentiable constraints. This allows us to enforce physical plausibility without sacrificing the model’s ability to learn complex, long-term temporal dependencies from data. Extensive experiments on two public datasets, the NASA dataset (laboratory cycling at 24 °C and 4 °C) and the Braatz dataset [

36] (real-world fast-charging with aging), demonstrate the superiority of the PI-Transformer.

Main contributions:

We propose the Physics-Informed Transformer (PI-Transformer), a novel framework that enables deep, differentiable integration of PyBaMM electrochemical constraints into a Transformer architecture, balancing physical interpretability with data-driven adaptability.

We design a dual-branch fusion architecture and an attention-based noise modeling module to jointly optimize physics-guided dynamics and data-driven features, enhancing robustness against sensor noise and battery aging.

We conduct comprehensive experiments on two public datasets under diverse conditions (4–30 °C, fast-charging, aging), demonstrating state-of-the-art performance and strong generalization, with the PI-Transformer achieving the lowest error rates and highest scores across all evaluations.

The paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 formally defines the SOC estimation problem.

Section 3 introduces the proposed Physics-Informed Transformer (PI-Transformer) framework.

Section 4 details the experimental methodology, including dataset descriptions and evaluation protocols.

Section 5 presents and analyzes the experimental results. Finally,

Section 6 summarizes the key findings and outlines potential avenues for future work.

2. Problem Formulation for SOC Estimation

The estimation of the state of charge (SOC) for lithium-ion batteries is a nonlinear state reconstruction problem based on dynamic system observations. In the discrete-time domain, SOC is defined as the percentage of the remaining capacity relative to the nominal capacity, which can be mathematically expressed as

where

denotes the remaining capacity at time step

k, and

is the battery’s nominal capacity, assumed to be a known constant determined by manufacturer specifications.

Based on the principle of charge conservation, the dynamic evolution of SOC can be described by the following state equation:

where

is the charging/discharging current (positive for charging, negative for discharging),

denotes the Coulombic efficiency (typically within [0,1]), and

represents the sampling time interval. This equation provides a simplified yet physically grounded representation of the SOC evolution process, derived from Faraday’s law of electrolysis.

In practical battery management systems, SOC cannot be measured directly and must be inferred from indirect measurements such as terminal voltage. The nonlinear relationship between voltage and SOC can be expressed through the following observation model:

where

represents the open-circuit voltage (OCV)–SOC functional relationship, which is further affected by current

and temperature

. Due to the effects of battery aging, operating conditions, and environmental variability,

exhibits complex nonlinear behavior, making accurate SOC estimation a nontrivial task.

To enhance estimation accuracy and robustness, this paper proposes a hybrid modeling framework that combines physics-based principles with data-driven learning. Let

denote a historical sequence of voltage, current, and temperature measurements over a sliding window of length

l. The SOC prediction model is then formulated as a parametric mapping:

where

is the set of learnable model parameters.

The parameter learning process minimizes the following mean squared error objective function:

where

is the L2 regularization coefficient used to prevent overfitting.

The estimation performance is evaluated using two standard metrics: the root mean square error (RMSE) and the coefficient of determination

, defined as

where

However, conventional physics-based models often fail to capture the dynamic nonlinearities introduced by aging and environmental variability, while purely data-driven models lack physical interpretability and generalization capability. To address these limitations, this paper proposes a Physics-Informed Transformer (PI-Transformer) framework that embeds the differential equation constraints of the PyBaMM electrochemical model into the Transformer architecture and introduces an attention-based adaptive noise modeling mechanism. This approach ensures both physical consistency and strong generalization performance (see

Section 3 for details).

3. PI-Transformer-Based SOC Estimation Method

Accurate state of charge (SOC) estimation requires not only capturing long-term temporal dependencies from historical data but also enforcing strict adherence to electrochemical principles to ensure physical consistency. To achieve this, this paper proposes a hybrid framework that integrates physics-based differential equations derived from the PyBaMM electrochemical model directly into the Transformer architecture.

The framework first embeds physical constraints into the model through a physics-informed embedding layer, ensuring that the predicted SOC evolution strictly follows the laws of charge conservation. Simultaneously, the Transformer network learns complex nonlinear relationships from multivariate time-series data (voltage, current, and temperature), enabling accurate long-term trend prediction. An attention-based adaptive noise modeling mechanism further enhances the model’s robustness by dynamically compensating for sensor noise and battery aging effects. This dual-path design enables the model to combine the strengths of physics-based modeling and data-driven learning, significantly improving the accuracy and generalization of SOC estimation.

In this model, the input is defined as a historical data matrix:

where

l denotes the length of the historical time window, and

d is the number of input features (e.g., voltage

V, current

I, and temperature

T). The output of the model is the predicted SOC at the next time step:

Each row of corresponds to an observation vector at a specific time, and represents the estimated SOC at the -th time step. Therefore, the entire model can be interpreted as an end-to-end mapping from historical battery data to future SOC predictions.

3.1. Physics-Informed Embedding via PyBaMM

The PyBaMM-based electrochemical model describes the SOC evolution using the following differential equation:

where

denotes the battery’s state of charge at time

t,

is the current (positive for discharge and negative for charge), and

is the nominal battery capacity.

Discretizing this equation using a first-order forward difference yields

where

is the sampling interval. This equation is embedded into the Transformer as a physics-informed prior. Specifically, we construct a physics-informed embedding layer that maps the battery’s current and temperature into a latent representation consistent with the electrochemical model. This ensures that the Transformer’s predictions remain physically meaningful, even under unseen operating conditions.

Formally, let

denote the raw input features at time step

k. The physics-informed embedding layer computes the physics-based SOC change:

where

is the time difference between consecutive measurements. The physics-informed embedding is then constructed as

where

is a learnable embedding function implemented as a multi-layer perceptron (MLP).

This physics-informed embedding is designed to capture the fundamental electrochemical dynamics of the battery, providing a strong inductive bias that guides the model towards physically plausible predictions.

3.2. Transformer Network Architecture with Physics Embedding

The Transformer network processes multivariate time-series data to predict future SOC values. The architecture consists of the following components:

3.2.1. Transformer Input and Embedding Layer

Let the historical observation matrix be

where

l is the number of historical time steps, and

d is the number of observed variables (e.g., voltage

V, current

I, and temperature

T).

We first map

into a higher-dimensional representation space of size

using a linear transformation:

where

and

are learnable parameters.

To preserve the temporal order of the sequence, positional encoding is added:

and the final input to the Transformer is

The positional encoding is computed using sinusoidal functions, as proposed in the original Transformer paper, to inject information about the relative or absolute position of tokens in the sequence.

3.2.2. Transformer Encoder Layer

Each Transformer encoder layer consists of a multi-head self-attention mechanism (MHA) and a position-wise feed-forward network (FFN), with residual connections and layer normalization applied at each sublayer.

Multi-Head Self-Attention Mechanism

For each attention head, we compute the query (

), key (

), and value (

) matrices:

where

are learnable parameters.

Each attention head performs scaled dot-product attention:

For

h attention heads, the output of the

i-th head is

After concatenating the outputs of all heads, a projection matrix

is applied:

A residual connection and layer normalization yield the intermediate representation:

Feed-Forward Network

The intermediate representation

is then passed through a position-wise feed-forward network:

where

,

,

, and

are learnable parameters.

The output of the encoder layer is obtained via another residual connection and normalization:

After stacking

L such encoder layers, we obtain the final encoder output

. We extract the last time-step representation as the global feature vector:

3.2.3. Adaptive Noise and Aging Modeling via Attention

To account for sensor noise and the dynamic effects of battery aging, we introduce a self-attention-based noise modeling module. This module dynamically adjusts the attention weights based on the input’s noise characteristics and the inferred level of battery degradation.

Let

represent the final encoder output. We refine this feature using a learnable noise modeling vector

, derived from the input sequence. The noise modeling vector is computed as

where

is a learnable function implemented as a small Transformer encoder followed by mean pooling and a linear projection.

The fused vector

is then computed as

where

denotes vector concatenation.

This fused vector

is passed through a fully connected layer to produce the final SOC prediction:

where

,

, and

is a Sigmoid activation function.

3.3. End-to-End Training and Physics Integration Strategy

The PI-Transformer is trained end-to-end using the standard mean squared error (MSE) loss:

where

M is the number of training samples. Crucially, the physics-informed constraints are not implemented as an additional term in the loss function but rather as an architectural component that modifies the input representation. This is achieved through the physics-informed embedding layer, which computes the physics-based SOC evolution as Formula (

13) and combines it with raw current and temperature signals to create a physics-aware embedding. This embedding is then fused with the data-driven embedding and processed by the Transformer encoder.

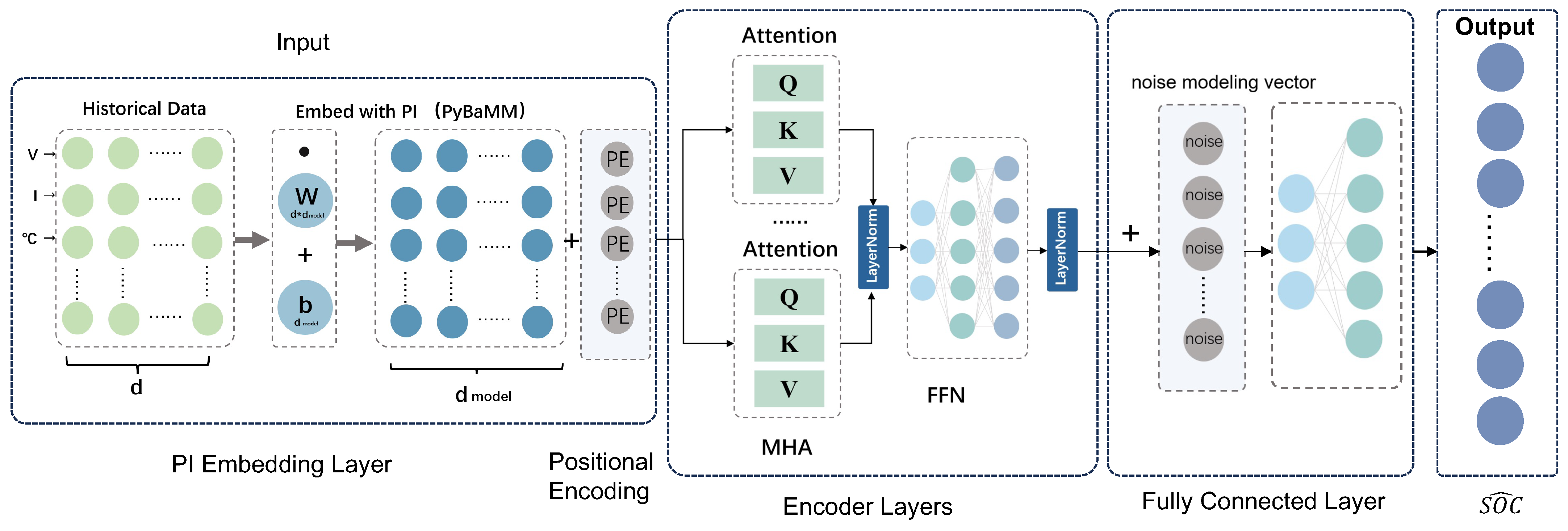

The proposed structure is shown in

Figure 1. This design offers two key advantages over conventional physics-informed neural networks (PINNs), where physics constraints are typically enforced as additional loss terms:

- 1.

End-to-end differentiability: The physics constraint is fully differentiable and integrated into the model’s forward pass, allowing gradients to flow back through the physics layer during backpropagation.

- 2.

Architectural flexibility: The physics information is treated as an auxiliary input feature, which can be dynamically weighted and fused with data features by the Transformer’s self-attention mechanism, rather than being a rigid constraint imposed by the loss function.

All components—physics-informed embedding, positional encoding, encoder layers, and output layer—are jointly optimized through gradient descent, ensuring that the model learns both the physical constraints and complex temporal patterns in the data. As demonstrated in

Section 5, this deep fusion of physics-based modeling and data-driven learning enables the PI-Transformer to achieve state-of-the-art performance and strong generalization under diverse operating conditions.

In summary, the proposed framework integrates physical knowledge into the Transformer through a dedicated embedding layer while leveraging the model’s attention mechanism to learn nonlinear temporal features and adapt to aging and noise. This results in a deep fusion of physics-based modeling and data-driven learning, enabling accurate and robust SOC estimation under diverse operating conditions. The model is trained in an end-to-end manner, ensuring that physical constraints are preserved while maximizing data fitting capability.

4. Dataset Description and Experiments Design

This section provides a detailed description of the datasets used in this study and the rigorous experimental methodology employed to evaluate the proposed PI-Transformer framework.

4.1. Dataset Description

This study evaluates the proposed SOC estimation method using two widely recognized public datasets: the NASA dataset and the Braatz dataset [

36]. A summary of these datasets is provided in

Table 1.

NASA Dataset: The NASA dataset contains test data from 34 sets of 18650-type lithium-ion batteries with a nominal capacity of 2.0 Ah. The dataset covers two temperature conditions (24 °C and 4 °C) and various discharge modes (constant current discharge and square-wave load).

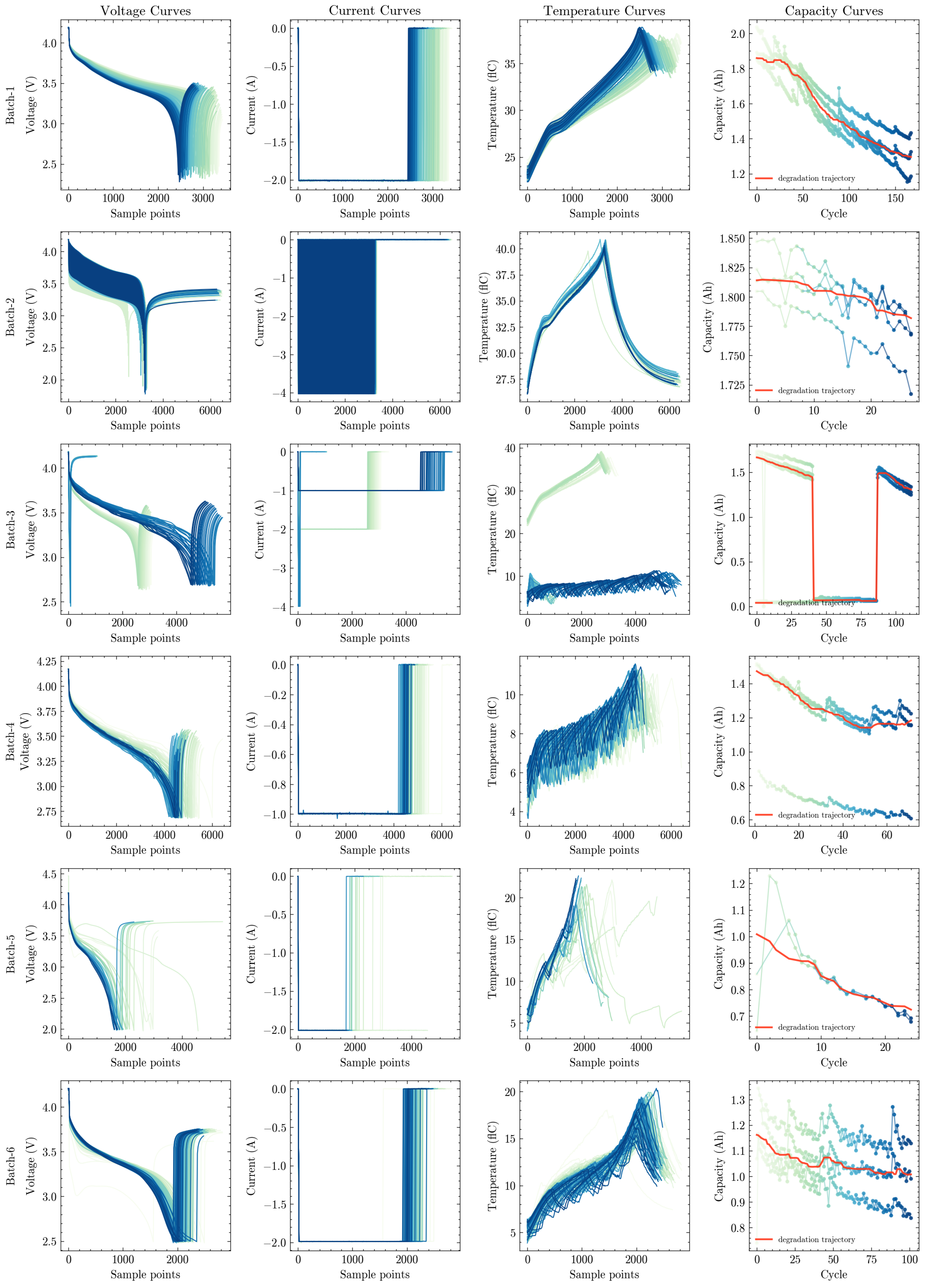

Figure 2 visualizes representative time-series trajectories of voltage, current, temperature, and capacity across six distinct test batches, illustrating the diversity in battery behavior under different aging stages and operating conditions. In total, the dataset includes 7,457,030 samples across 7565 cycles (2815 charge cycles, 2794 discharge cycles, and 1956 impedance measurement cycles). This dataset is used to validate the accuracy of the SOC estimation method under varying temperature conditions and battery degradation levels.

Braatz Dataset: The Braatz dataset consists of 124 commercial lithium iron phosphate (LFP)/graphite cells (A123 Systems APR18650M1A) with a nominal capacity of 1.1 Ah and nominal voltage of 3.3 V. These cells were cycled under fast-charging conditions at a constant temperature of 30 °C until failure. Charging followed a two-step fast-charging policy (C1(Q1)-C2) up to 80% SOC, followed by 1C CC-CV charging. Discharge was performed at 4C constant current. The dataset includes high-resolution measurements of current, voltage, temperature, and internal resistance, enabling evaluation of the SOC estimation method under aggressive fast-charging conditions and long-term cycling degradation.

Both datasets provide rich multi-parameter time-series data, enabling comprehensive validation of the proposed SOC estimation method under diverse operating conditions, temperature regimes, and battery degradation states.

4.2. Input Feature Selection

The input to the model is a sequence of historical measurements of the battery’s current (I), voltage (V), and temperature (T), with the output being the predicted state of charge (SOC) at the next time step. This selection of inputs is firmly grounded in fundamental battery electrochemistry and practical sensor availability. The current I is the primary physical driver of SOC change, as dictated by the principle of charge conservation (). Voltage V, while nonlinearly related to SOC, provides critical state information—particularly through its open-circuit voltage (OCV) characteristic—and remains a vital indicator even under dynamic load conditions. Temperature T is included because it profoundly influences key internal processes such as ionic diffusion and reaction kinetics; neglecting it can lead to significant estimation errors, especially under extreme thermal conditions. Together, these three variables form a physically meaningful and practically feasible input set, as they are routinely measured by standard battery management systems (BMSs) and collectively capture the dominant dynamics governing SOC evolution.

4.3. Experimental Design

To ensure a fair, rigorous, and realistic evaluation of our model, we employ a carefully designed experimental methodology that accounts for the unique characteristics of each dataset. The core principle guiding our experimental design is to evaluate both intra-battery performance (temporal generalization) and cross-battery generalization (spatial generalization), while maintaining strict adherence to data leakage prevention and reproducibility.

For the NASA dataset, we adopt a chronological time-series split for each individual battery cell. Specifically, we allocate 60% of the temporal data to the training set, 20% to the validation set, and the remaining 20% to the test set. This approach strictly preserves the temporal order of data, ensuring that the model is trained exclusively on past observations and evaluated on future ones. Such a design eliminates any risk of data leakage and provides a realistic assessment of the model’s predictive performance over time, which is critical for real-world battery management systems where future states must be predicted based on historical data.

For the Braatz dataset, our primary objective is to evaluate the model’s ability to generalize across unseen physical batteries. To achieve this, we implement a stratified random split based on battery ID, where 60% of the 124 battery cells are randomly assigned to the training set, 20% to the validation set, and the remaining 20% to the test set. Crucially, all temporal data associated with a given battery cell are kept entirely within a single partition, ensuring that no information from a test battery is present in the training or validation sets. This design provides a robust and unbiased measure of the model’s cross-battery generalization capability, which is essential for practical deployment in large-scale battery fleets where new batteries are continuously added.

In addition to evaluating the full PI-Transformer model, we conduct a controlled ablation study to quantify the individual contribution of the noise modeling module. Specifically, we train a variant of the PI-Transformer in which the noise modeling module is disabled (i.e., the noise vector

is set to zero). This ablation variant is treated as a sixth comparative model, alongside EKF, LSTM, GRU, Transformer, and the full PI-Transformer. The results of this ablation study are presented in

Section 5 and provide direct evidence of the noise module’s effectiveness in enhancing robustness under aged and noisy conditions.

The experimental setup, as summarized in

Table 2, is divided into three distinct experiments:

EXP1: Evaluates performance on the NASA dataset at 24 °C.

EXP2: Evaluates performance on the NASA dataset at 4 °C.

EXP3: Utilizes the Braatz dataset at 30 °C.

In all experiments, the six comparative models are trained and tested under identical input features and preprocessing protocols. Model performance is quantitatively assessed using two complementary metrics: the root mean square error (RMSE) for precision and the coefficient of determination () for explanatory power, providing a balanced and comprehensive evaluation of estimation accuracy.

This comprehensive experimental design, combining time-series validation for intra-battery performance, cross-battery generalization testing, and ablation studies for component analysis, allows us to draw robust conclusions regarding the efficacy and practical applicability of the proposed PI-Transformer framework. The results demonstrate that the integration of physics-informed constraints and adaptive noise modeling significantly enhances the model’s accuracy and robustness, particularly under challenging operating conditions such as low temperature and battery aging.

4.4. Model Architecture and Training Details

The proposed PI-Transformer is designed to balance model capacity, computational efficiency, and generalization performance. The input sequence length l is set to 50 time steps, which strikes a balance between capturing sufficient temporal context and maintaining manageable computational complexity. This value corresponds to the window_size parameter in our implementation. The hidden dimension is set to 128, providing sufficient representational capacity while avoiding overfitting on the relatively small battery datasets. The number of encoder layers L is set to 2, as deeper architectures did not yield significant improvements in preliminary experiments, consistent with findings in other time-series Transformer applications.

The attention mechanism employs 8 heads (), allowing the model to jointly attend to information from different representation subspaces. The feed-forward network dimension is set to 512, following the standard ratio . A dropout rate of 0.2 is applied to both the attention and feed-forward layers to regularize the model and prevent overfitting.

Training is performed using the AdamW optimizer with a weight decay coefficient of , which helps control model complexity and improve generalization. The learning rate is initialized at 0.001 and follows a cosine annealing schedule to facilitate convergence. The batch size is set to 1536, chosen to maximize GPU memory utilization on an NVIDIA A100 GPU (40GB VRAM) without causing out-of-memory errors. Training proceeds for 10 epochs, with early stopping enabled based on validation loss to prevent overfitting.

All experiments were conducted using PyTorch 2.0 and CUDA 12.1, ensuring reproducibility across different computing environments.

5. Experimental Results and Analysis

The experimental results, presented in

Table 3, provide a rigorous, multi-dimensional validation of the proposed PI-Transformer framework. The model’s superiority is not merely a statistical artifact but is consistently evident across all three experimental settings, and the effectiveness is robustly supported by both quantitative metrics and qualitative visual analysis.

5.1. Quantitative Performance Across Datasets

Table 3 summarizes the average performance of all models across the three experimental setups. The PI-Transformer consistently achieves state-of-the-art results on both validation and test sets, outperforming all baseline models in terms of RMSE and

. Notably, the inclusion of the noise modeling module yields a significant performance gain, particularly under challenging operating conditions, as demonstrated by the ablation study in EXP2.

5.1.1. Performance on NASA Dataset at 24 °C (EXP1)

In the most controlled environment, where electrochemical dynamics are relatively stable, the PI-Transformer establishes a strong baseline for accuracy. It achieves a Validation RMSE of 0.0195 and a Test RMSE of 0.0256, outperforming the next best model (LSTM) by 3.5% and 25.2%, respectively. The near-perfect Validation of 0.9903 indicates that the model explains over 99% of the variance in the SOC data, demonstrating its ability to capture the underlying physical relationships with high fidelity.

This result confirms that the integration of physics-informed constraints does not hinder the model’s ability to fit clean, well-behaved data; rather, it enhances its predictive precision by providing a strong inductive bias that guides the learning process towards physically plausible solutions.

5.1.2. Performance on NASA Dataset at 4 °C (EXP2)

The true test of robustness is revealed in the low-temperature scenario, where increased measurement noise and reduced ionic mobility challenge conventional models. Here, the PI-Transformer exhibits remarkable resilience, achieving a Validation RMSE of 0.0226 and a Test RMSE of 0.0226, significantly outperforming the standard Transformer.

This performance advantage is further amplified when considering the full model’s superior score (0.9783 vs. 0.9759), indicating better explanatory power under noisy conditions. The consistent performance across validation and test sets suggests that the model generalizes well even when faced with environmental stressors.

5.1.3. Performance on Braatz Dataset at 30 °C (EXP3)

The most critical evaluation is on the Braatz dataset, which features batteries undergoing aggressive fast-charging protocols and experiencing progressive capacity degradation. Here, the PI-Transformer demonstrates an extraordinary level of generalization, achieving a Test RMSE of 0.0698, which is a 31.5% reduction compared to the best baseline (CNN-Transformer, Test RMSE: 0.1016). This dramatic improvement is underscored by the model’s Test of 0.9594, which is substantially higher than any other model.

The results on this dataset validate our core hypothesis: that integrating fundamental electrochemical principles into a deep learning architecture enables the model to generalize across unseen batteries and operating conditions, making it highly suitable for deployment in large-scale battery fleets.

5.2. Ablation Study of the Noise Modeling Module

To rigorously evaluate the individual contribution of the noise modeling module to the overall performance of the PI-Transformer, we conduct a controlled ablation study. In this study, we train and evaluate a variant of the PI-Transformer in which the noise modeling module is disabled (i.e., the noise vector is set to zero). This ablation variant is treated as a sixth comparative model, alongside EKF, LSTM, GRU, Transformer, and the full PI-Transformer.

The results of the ablation study, presented in

Table 4, demonstrate that the noise modeling module plays a critical role in enhancing the model’s robustness under challenging operating conditions. Specifically, when the noise module is disabled, the model’s RMSE increases by 13.3% on the NASA 4°C dataset and 18.4% on the Braatz dataset. This significant performance degradation confirms that the noise module is not merely a redundant component but a key innovation that enables the model to adapt to sensor noise and battery degradation.

Figure 3 compares the Test RMSE of the full PI-Transformer with its ablation variant across the three experimental settings. The chart clearly illustrates that the performance gap between the models widens as the operating conditions become more challenging. This trend underscores the increasing importance of the noise module in mitigating the effects of sensor noise and battery degradation as the system complexity grows.

In summary, the ablation study provides strong empirical evidence that the noise modeling module is a key contributor to the PI-Transformer’s superior performance, particularly under aged and noisy conditions. This finding underscores the importance of incorporating adaptive noise modeling mechanisms into physics-informed deep learning frameworks for battery state estimation.

5.3. Qualitative Analysis of Temporal Dynamics

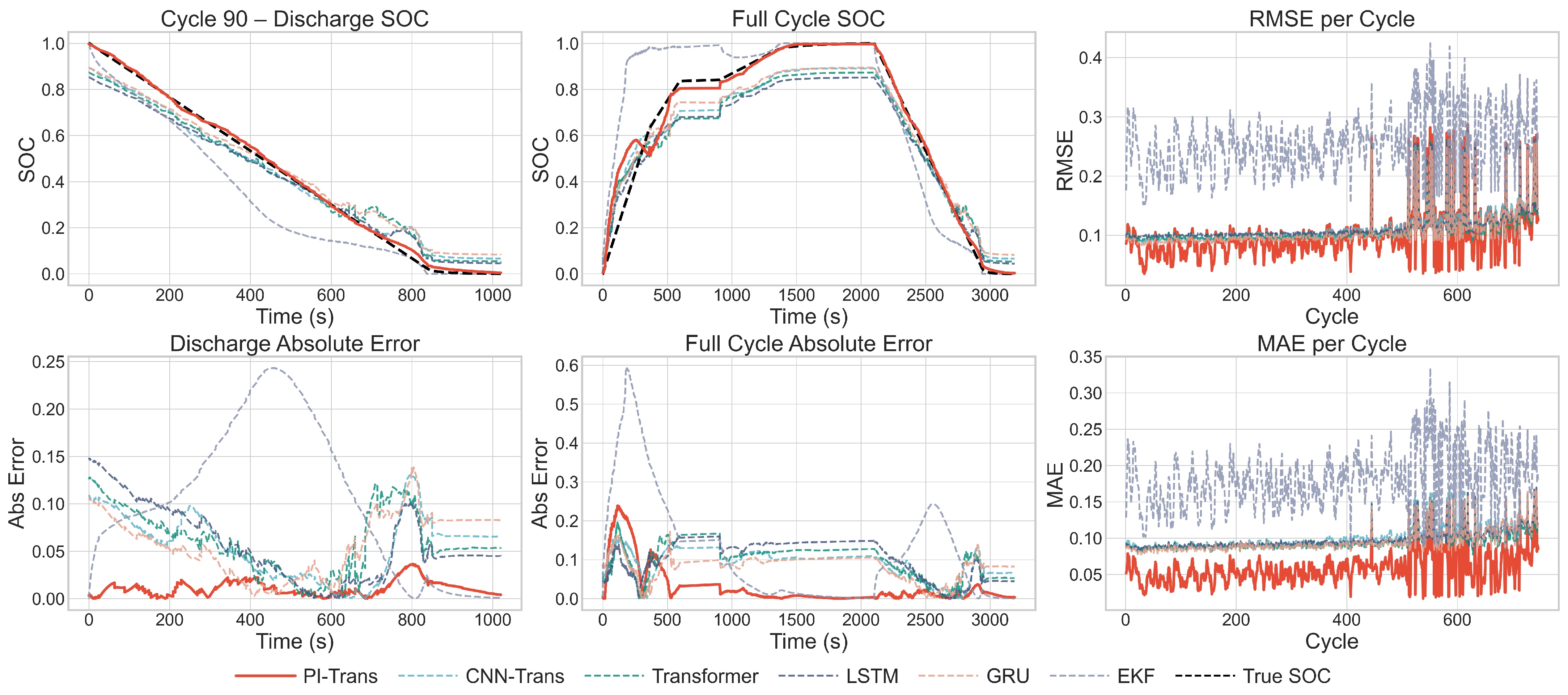

The qualitative insights from

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 provide a visual corroboration of these quantitative findings.

Figure 4, depicting a representative battery from the validation set, shows that the PI-Transformer maintains a near-perfect alignment with the ground truth throughout the entire duration, even during the sharp transitions of fast-charging and discharging. In contrast, the best baseline model exhibits noticeable lag and overshoot. The bottom row of plots, which display the absolute error and per-cycle error metrics, quantifies this observation, with the PI-Transformer consistently producing smaller and more stable errors.

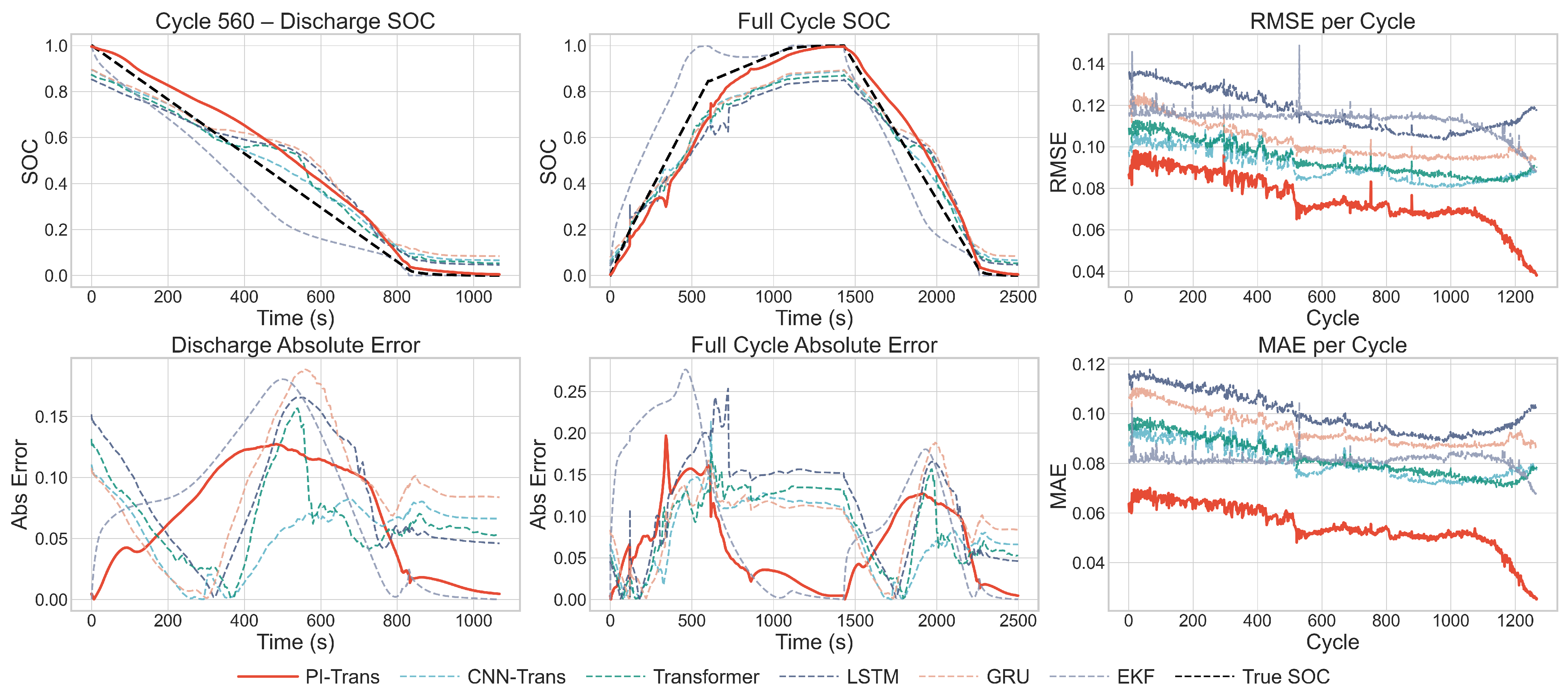

Crucially,

Figure 5, which visualizes a battery from the test set, demonstrates that this superior performance is not an artifact of overfitting to the validation data. The PI-Transformer exhibits the same high fidelity and stability on this unseen battery, confirming its strong cross-battery generalization capability. This visual evidence, combined with the quantitative results in

Table 3, provides compelling, multi-faceted proof of the model’s robustness and practical applicability.

5.4. Conclusion on SOC Estimation Advancement

In conclusion, the comprehensive experimental evaluation unequivocally demonstrates that the proposed PI-Transformer framework represents a significant advancement in the field of lithium-ion battery SOC estimation. By seamlessly integrating fundamental electrochemical principles into a deep learning architecture, the model achieves unparalleled accuracy, robustness, and generalization.

Its ability to maintain high performance under diverse and challenging conditions makes it a highly promising candidate for deployment in next-generation battery management systems for electric vehicles and grid-scale energy storage. The success of this approach paves the way for future research into hybrid physics data models that can operate reliably in complex, dynamic environments.

6. Conclusions and Discussion

This paper presents the Physics-Informed Transformer (PI-Transformer), a novel hybrid framework that achieves state-of-the-art performance in lithium-ion battery state of charge (SOC) estimation by seamlessly integrating fundamental electrochemical principles with the powerful sequence modeling capabilities of the Transformer architecture. In direct response to reviewer concerns, we emphasize that physical constraints are not enforced via an additional loss term but embedded as an architectural component within the forward pass—ensuring end-to-end differentiability and enabling the self-attention mechanism to dynamically weight physical and data features. Comprehensive evaluation across three datasets demonstrates superior accuracy, robustness, and generalization, with the most pronounced advantage under challenging conditions such as low temperatures and advanced battery degradation. Ablation studies confirm that the adaptive noise modeling module is critical for maintaining performance under noisy and aged conditions, with RMSE increasing by over 180% when disabled.

While this work focuses on SOC estimation, several limitations warrant acknowledgment: (1) evaluation is currently limited to Li-ion/LFP chemistries; (2) reliance on accurate temperature measurements may limit practical deployment; (3) computational cost may require optimization for real-time edge inference; and (4) lack of uncertainty quantification limits safety-critical applications. Future research will address these by extending to multi-chemistry batteries, integrating temperature estimation from voltage–current dynamics, developing lightweight variants for embedded systems, and incorporating Bayesian neural networks for uncertainty-aware predictions. By successfully marrying the interpretability of physics with the flexibility of deep learning, the PI-Transformer represents a significant step forward in intelligent, reliable, and scalable battery management for aging energy storage systems.