Abstract

Young’s modulus is a key parameter to describe the compressive behavior of battery electrodes and is therefore frequently employed in mechanical models. In most studies, this property is determined using pristine electrodes. However, during electrochemical cycling, lithium insertion and extraction can alter the mechanical response of the active materials. The literature lacks SOC-dependent compression data of electrodes with different active materials. Especially for LFP electrodes, no SOC dependencies have been reported. This study closes this gap by performing compression tests on graphite, NMC, and LFP electrodes at different states of charge. The results show that the stiffness of graphite and NMC electrodes increases with higher lithium contents, whereas the compressive behavior of LFP remains independent of the lithium content. These findings are consistent with material-level properties reported in the literature. Two hypotheses are proposed to explain this behavior: one hypothesis is related to the contribution of active material particles to electrode deformation and the other hypothesis is related to microstructural changes governed by particle diameter.

1. Introduction

Energy storage devices and especially lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) are considered a cornerstone in transitioning to a CO2-neutral society. LIBs are used in a multitude of personal electronic devices, large-scale energy storage systems, as well as in electric vehicles (EVs). Despite primarily being electrochemical energy storage devices, understanding LIBs requires a combination of several disciplines. Besides integration into an electrical system and understanding of electrochemical processes, consideration of mechanical aspects has recently gained increasing interest.

Electrode stacks or jelly rolls in LIBs usually experience a certain compressive force, either externally applied (pouch cells, prismatic cells) or by design (cylindrical cells). Understanding how this mechanical compression impacts cell performance and longevity has been a target in various publications [1,2,3,4,5,6], where more of the literature on these topics can be found. Once experimental methods cannot capture certain effects, models are often used to gain further understanding. For example, intercalation expansion of active materials results in volume expansion on the particle and electrode level, effectively leading to changes in coating thickness and porosity, which has been shown both experimentally [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15] and in simulations [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. Due to mechanical constraints, e.g., due to the cell casing, expansion is limited. The resulting complex interplay can experimentally be measured with great effort only. To investigate this behavior in simulations, material properties are required as model inputs. In particular, Young’s modulus is a key property for many modeling approaches to capture the behavior on particle level, electrode level, or cell level.

However, parameters like Young’s modulus differ depending on the scope. On material or particle level, for example, for an active material particle, the bulk Young’s modulus of the active material is the relevant quantity. On electrode level, however, the effective value of Young’s modulus differs from that of the bulk value of the active material due to the porous nature of the electrode as well as due to the presence of several components, e.g., active material, binder, and conductive agents. While dependencies of Young’s modulus on the binder system or porosity are known in the literature [21,22], dependencies on the state of lithiation (or full-cell state of charge (SOC)) are hardly investigated at all. This is primarily due to the fact that pristine samples are easier to handle than those at different states of lithiation.

1.1. MaterialLevel

Data on Young’s modulus on material level for graphite [23,24], for example, suggest an increase in Young’s modulus with increasing lithium content from 32 GPa to 109 GPa at full lithiation. However, for common cathode systems like lithium-iron-phosphate (LFP) and nickel-manganese-cobalt-oxide (NMC), available data in the literature remain scarce. Young’s modulus for LFP on material level is reported to be approx. 125 GPa independent of the lithium content [24,25], or to increase slightly from 108 GPa to 118 GPa with increasing lithium content [25]. Using first-principles calculations, Min and Cho [26] report Young’s modulus for NMC811 to vary between approx. 15 GPa and 300 GPa, depending on the lithium content, on the in-plane or out-of-plane direction of the crystal lattice, and on forces acting in the compressive or tensile direction. Using nanoindentation tests, Xu et al. [27] have also shown Young’s modulus to increase with increasing lithium content, but they report values from 111 GPa to 142 GPa. Overall, Young’s modulus of NMC811 on material level increases with increasing lithium content, a similar trend that can be seen in graphite.

1.2. Electrode Level

Few publications also investigated the evolution of Young’s modulus on electrode level with increasing lithium content. Most of the publications are on graphite electrodes. Li and Wang [28] used real-time curvature measurement of a cantilever electrode and showed that Young’s modulus increases from 9 GPa to 32 GPa at 60% lithiation. Zhou et al. [29] used a mathematical model to calculate the effective modulus of the electrode and report an increase from 12 MPa to 30 MPa at full lithiation, which also captures the trend in their experimental data from tensile tests. Most of the literature, however, utilizes compression tests and provides a stress–strain curve. For convenience, we estimated a linearized Young’s modulus from these non-linear stress–strain curves to enable a comparison. The resulting Young’s modulus from compression tests falls in a range between 27 MPa and 155 MPa [7,20,30,31,32] when no lithium is stored in the graphite electrode. Additionally, Sauerteig et al. [7] report an increase in stiffness by a factor of approx. 2 for a cycled compared to an uncycled electrode when both are delithiated. Xu et al. [33] also tested graphite anodes at 0% and 30% SOC and found a stiffening by approx. 20%, although their tests were carried out at pressures between 10 MPa and 50 MPa. In summary, this shows that characterization after formation is highly relevant and that Young’s modulus further changes with SOC. Overall, Young’s modulus for pristine graphite electrodes differs widely in the literature. Still, a trend of stiffer graphite electrodes with increasing lithium content is visible on electrode level and is consistent with reports on material level. However, this trend has not yet been measured via compression tests.

Characterization of LFP and NMC on electrode level is less well investigated in the literature. For NMC in general (various atomic compositions), linearized values for Young’s modulus between 30 MPa and 270 MPa [6,7,12,30,31] are reported. For LFP, the limited data on Young’s modulus on electrode level suggest a value of 275 MPa, based on in-plane and out-of-plane compression tests [34]. Sedlatschek et al. [35] also report a value of 47.3 GPa via nanoindentation and a dependency on porosity. However, their tests were on secondary particle level with nano-porous particles and not on electrode level. Generally, NMC and LFP cathodes tend to be stiffer than graphite anodes, which is in line with their higher Young’s modulus on material level.

1.3. Problem Statement & Goal

In summary, different experimental methods for characterization are discussed in the literature, especially on electrode level. For example, electrode cantilever curvature tests [28], nanoindentation tests [35], and compression tests [6,7,12,20,30,31,32,33] can be found, with compression tests being the most common method. Despite being the most common method, the experimental procedure for compression tests is not uniform and differs regarding parameters like force-controlled or displacement-controlled tests, preload, strain rate, maximum strain or stress, or number of mechanical cycles. This ambiguity makes identification of certain dependencies by comparison of existing studies difficult. Especially the dependency of Young’s modulus on the electrode state of lithiation (or full-cell SOC) has hardly been investigated in the literature. As mentioned above, only a few studies conducted such experiments on electrode level. Especially due to different experimental methods and procedures, comparability is not necessarily given among them. To the best of our knowledge, no publication has yet experimentally investigated Young’s modulus on electrode level at different SOCs consistently for several active materials.

In this work, we aim to close this gap in the literature by determining the Young’s modulus of three electrode materials that are among the most commonly used in lithium-ion batteries [36], namely, artificial graphite (AG), Li(Ni0.8Mn0.1Co0.1)O2 (NMC811), and LFP, through compression tests at 0%, 50%, and 100% full-cell SOC. We explicitly focus on compressive and not on tensile testing because tensile strains and stresses in through-plane direction typically do not occur during normal operation of stacked lithium-ion batteries. In the following, we first explain the experimental setup and procedure. Afterwards, we show the SOC dependency of the three different electrodes and provide possible explanations for the observed behavior.

2. Experimental Procedure

2.1. Electrodes

Three distinct electrodes were investigated in this study. The electrodes were harvested from two different 5 Ah pouch cell types from LiFun Technology (Zhuzhou, China), already filled with electrolyte. Both cells exhibit an AG anode and differ in the cathode, with one containing NMC811 and the other LFP as cathode material. The specifications of the pristine electrodes are given in Table 1. The AG anode from the cell was investigated, which features a coating thickness of 76.5 μm per side and a porosity of 33%. The NMC811 electrode exhibits a coating thickness of 52 μm and a porosity of 31%, while the LFP electrode has a coating thickness of 84 μm and a porosity of 35%.

Table 1.

Specification of the pristine electrodes, given by the manufacturer.

2.2. Preconditioning

Before harvesting, the cells underwent 10 full electrochemical cycles to ensure a stable and homogeneous state. Cycling was performed using a battery cycler (CTS, Basytec, Asselfingen, Germany) inside a temperature chamber (VC 4060, Vötsch, Balingen, Germany) set to 20 °C. The cycling procedure consists of a constant current (CC) phase followed by a constant voltage (CV) phase. The CC phase during charging and discharging was carried out at a C-rate of C/2. The voltage window was to for the NMC811 cell and to for the LFP cell, with a cutoff current for the CV phases of C/20 applied at both upper and lower cutoff voltages. The completely discharged cells were then preconditioned to 0%, 50%, or 100% full-cell SOC with a CC of C/20 via coulomb counting. The SOC is defined as the charge throughput starting from the completely discharged state divided by the maximum capacity of the cell as determined by the last cycle (capacity of the CC and CV discharge step combined). After preconditioning and before opening the cells (see next section), the cells were again allowed to rest for at least 24 h.

2.3. Electrode Harvesting and Preparation

The preconditioned cells at the different SOC levels were opened inside an argon-filled glove box (O2 and H2O < 1.0 ppm, M. Braun Inertgas-Systeme GmbH, Garching bei München, Germany). The wound electrode-separator assembly was unrolled and carefully separated to avoid short circuits. Circular electrode samples with a diameter of 18 mm were punched from the harvested electrodes. These discs were washed in dimethyl carbonate for 2 hours to remove lithium salt residues originating from the electrolyte. For each combination of electrode type and SOC, 24 samples were stacked and placed inside a pouch bag, which was sealed under a vacuum of 50 mbar using a vacuum sealing machine (Harro Höfliger Verpackungsmaschinen GmbH, Allmersbach im Tal, Germany). No electrolyte or solvents were added. Disassembly, sample preparation, and sealing were carried out inside the glovebox.

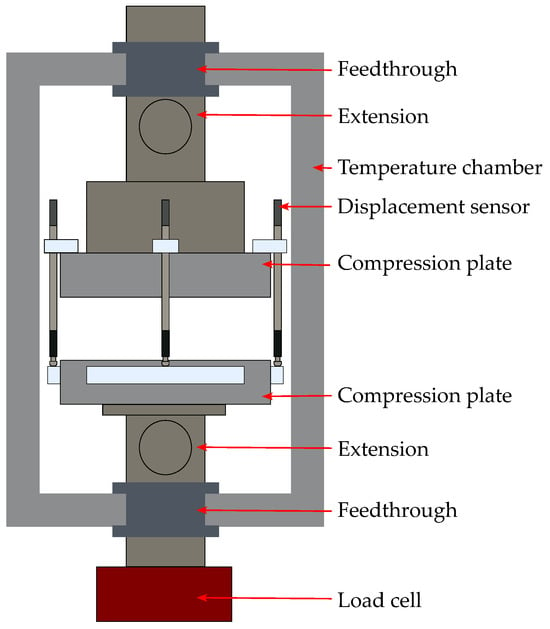

2.4. Mechanical Test Setup

The compression test setup introduced in our previous studies [31,37] and shown in Figure 1 was used for investigating the mechanical compression behavior of the samples. The test setup consists of a universal testing machine (UTM) (AllroundLine Z020/TH, ZwickRoell, Ulm, Germany), an integrated temperature chamber (KB23, Binder, Tuttlingen, Germany), and three tactile displacement sensors (GT2, Keyence, Osaka, Japan). The UTM is equipped with a load cell (Xforce K, ZwickRoell, Germany) that provides an accuracy of ±1% for forces below 200 N and ±0.5% for forces above 200 N. The displacement sensors operate with an accuracy of ±1 μm. The temperature was set to 25 °C for all compression tests.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the mechanical test setup, showing the test area of the UTM, the load cell, the integrated temperature chamber, and the displacement sensors [31,37].

2.5. Mechanical Test Procedure

The sample stacks, sealed in a pouch bag, were placed on the lower compression plate of the UTM. A circular steel stamp with a diameter of 18 mm was positioned on top of the sample cell. The compression tests were performed by increasing the pressure from a preload of 0.5 MPa to a maximum of 2.5 MPa over a period of 6 hours. The comparably high preload was necessary to ensure proper contact between the pouch foil and the electrode stack. A correction curve was recorded with a steel reference sample sealed in a pouch bag to compensate for the compressibility of the pouch bag and test setup and was subtracted in the following from the measured curve.

2.6. Electrical Potential Measurement

Since the samples have been harvested from full cells at different SOCs, the electrical potential on half-cell level is of particular interest to describe the material state. To this end, coin half cells were assembled. The working electrode is represented by a sample of either AG, NMC, or LFP (14 mm diameter) from the single-sided coated area of the electrodes. Two glass fiber separators (16 mm diameter, 260 μm thickness each, VWR, type 691, Radnor, PA, USA) were used to separate the working electrode from the lithium metal counter electrode (15.6 mm diameter). The cell was flooded with 80 μL electrolyte (LP572, Solvionic, Toulouse, France).

Finally, the cells were placed in a climate chamber at 25 °C (KT170, Binder GmbH, Tuttlingen, Germany) and the electrical potential of the working electrodes vs. lithium metal was measured using a battery tester (CTS, Basytec, Asselfingen, Germany).

3. Results and Discussion

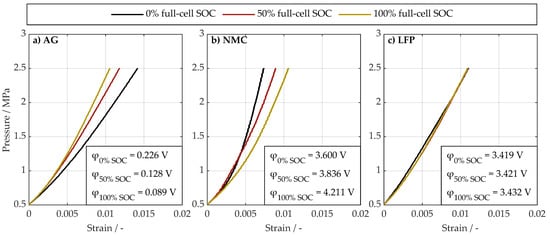

Figure 2 shows the results of the compression tests for the AG anode, the NMC811 cathode, as well as the LFP cathode as a stress–strain diagram. The correction curve to compensate for the compressibility of the pouch bag and the machine stiffness is already accounted for here. Different lines indicate the different SOCs. The half-cell electrical potential (φ) vs. lithium metal is shown in the legend for each full-cell SOC.

Figure 2.

Stress–strain relationship of the (a) artificial graphite (AG), (b) nickel-manganese-cobaltoxide

(NMC), and (c) lithium-iron-phosphate (LFP) electrode samples at 0%, 50%, and 100% full-cell SOC. The measured electrical potential of the harvested electrode materials vs. lithium metal is denoted as φ for each tested sample.

The reproducibility of the measurements was verified by performing three compression tests on NMC and LFP electrodes at 50% SOC. The resulting relative standard deviation of the measured Young’s modulus values was approximately 4%. As will be shown later, the SOC-dependent variations in stiffness are significantly more pronounced for AG (up to %) and NMC (up to %) electrodes. Therefore, it can be assumed that the observed trends are reliable and not influenced by experimental uncertainty.

Regarding the AG anode, a stiffer behavior can be observed with increasing SOC. This has already been reported in the literature on material level [23,24] as well as on electrode level [28,29]. However, a threefold increase in Young’s modulus on material level as reported in Refs. [23,24] is not directly translated to electrode level, as evident in Figure 2a. A linearized Young’s modulus (linearized between 0.5 MPa and 2.5 MPa) yields a value of 141 MPa at 0% full-cell SOC, which is slightly higher than the range found in the literature discussed above [7,20,30,31,32]. Slightly higher results are reasonable, since the preload of 0.5 MPa is also higher compared to the literature. This is especially important for graphite anodes compared to cathodes, as those anodes tend to be softer than cathodes. With increasing SOC, the linearized Young’s modulus increases up to 190 MPa at 100% full-cell SOC.

Regarding the NMC811 cathode, softening with increasing SOC is observed in Figure 2b, which has also been observed on material level (increasing Young’s modulus with increasing lithium content) [26,27]. Again, the magnitude by which Young’s modulus changes does not directly translate from material to electrode level. The linearized Young’s modulus of 271 MPa at 0% full-cell SOC is within the range known from the literature [6,7,12,30,31]. With increasing SOC, the linearized Young’s modulus decreases to 188 MPa at 100% full-cell SOC.

Regarding the LFP cathode in Figure 2c, no trend with increasing SOC can be observed at all, which is also in line with the literature on material level [24,25]. The linearized Young’s modulus with a value of approx. 182 MPa for all three tested SOC values is lower than known from the literature [34]. This finding is most likely based on the fact that Lai et al. [34] performed tests in in-plane instead of out-of-plane direction, from which they estimated Young’s modulus of the LFP cathode. However, compression in in-plane direction is suspected to yield a higher Young’s modulus compared to out-of-plane tests because of the anisotropic compression behavior of electrode sheets (coating and current collector foil). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time SOC-dependent data for LFP cathodes are shown.

Each of the two independent hypotheses below provides a possible consistent explanation for the observed SOC-dependent compression behavior.

- The electrode compression is dominated by compression of the porous structure. Soft binder and movement of active material particles account for the majority of the total compression. Small points of contact between active material particles can result in high local pressure values, which can lead to particle deformation. This particle deformation contributes a small fraction to the total electrode deformation. With changing lithium content in the electrode, Young’s modulus of the inactive components does not change. However, Young’s modulus of graphite and NMC increases with lithium content on material, while Young’s modulus of LFP remains unchanged. Thus, the behavior of Young’s modulus propagates from material to electrode level via the small contribution of active material deformation to the total electrode compression.

- The particle size of the LFP electrode is about an order of magnitude smaller than that of the AG and NMC electrodes. Consequently, changes in the porous structure due to intercalation expansion/contraction may be less pronounced for the LFP electrode with smaller particles compared to the AG and NMC electrodes with larger particles. Thus, the SOC-dependent compression of the AG and NMC electrodes could be attributed to microstructural changes induced by particle expansion and contraction, whereas the smaller LFP particles have a reduced impact on the electrode microstructure, resulting in the absence of an SOC-dependent trend on electrode level.

These hypotheses can describe the observed behavior for all three investigated samples in Figure 2. The nature of the microstructure of each electrode will also play an important role. Changes in the volume fractions of each phase will alter the overall value of Young’s modulus. However, considering that most commercially available electrodes focus on energy density and proper dispersion of constituents is given, many commercially available electrodes are expected to be quite comparable in this regard. Thus, we believe that the general behavior should not significantly differ from what we observe here. However, further studies are required to support or refute the proposed hypotheses, for example by testing electrodes that only differ in particle diameter. Additionally, the impact of different procedures for compression testing could also be investigated, for example using different preloads, strain rates, or number of mechanical cycles, as discussed in [32]. Lastly, results may vary when tested with wetted samples instead of dry conditions due to interactions between electrolyte and binder. Binders might swell, become softer, or become more rigid upon wetting, depending on the chosen electrolyte and binder type [38,39,40], altering the overall electrode behavior. However, it is expected that SOC-dependent compression behavior is still visible even under wet conditions.

4. Conclusions

In this study, compression tests of graphite, NMC, and LFP electrodes at different full-cell SOC levels were conducted, and Young’s modulus was estimated via linearization. The results demonstrate that graphite anodes stiffen with increasing SOC, while NMC cathodes soften. This trend is consistent with findings on material level known from the literature. On the other hand, LFP electrodes show no SOC-dependent variation in compressive behavior, which also aligns with the properties on material level reported in the literature. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that SOC-dependent compression tests for LFP on electrode level are published.

Based on our findings, we present two independent hypotheses to explain the observed behavior. The first hypothesis assumes that electrode compression is mainly governed by deformation of the porous structure, with active material deformation making only a minor contribution that nonetheless transmits material-level SOC-dependent stiffness changes to the electrode scale. The second hypothesis argues that intercalation-induced microstructural changes are dependent on the particle diameter, where larger particles cause more pronounced microstructural deformation and thus observable SOC-dependent compression behavior.

Due to consistent experimental procedures, our findings provide a comparable overview of the SOC-dependent compression behavior of different electrode materials. Our results are consistent with values reported in the literature. However, further studies are required to support or refute the proposed hypotheses. A reliable Young’s modulus is especially important for simulative investigations to correctly capture and describe the mechanical response.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.S. and A.D.; methodology, T.S. and A.D.; validation, T.S. and A.D.; investigation, T.S. and S.K.; data curation, T.S. and A.D.; visualization, T.S. and A.D.; project administration, T.S. and A.D.; resources, A.J.; supervision, A.J.; funding acquisition, A.J.; writing—original draft preparation, T.S. and A.D.; writing—review and editing, T.S., A.D., S.K. and A.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The results presented were achieved in association with an INI.TUM project, funded by the AUDI AG. Additionally, this work was financially supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) under grant number 03XP0425 (TUBE).

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request due to restrictions (AUDI AG confidentiality guidelines). Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tzu-Chen Hung for his assistance in electrode preparation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of this study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AG | artificial graphite |

| CC | constant current |

| CV | constant voltage |

| LFP | lithium-iron-phosphate |

| LIB | lithium-ion battery |

| NMC | nickel-manganese-cobalt-oxide |

| NMC811 | Li(Ni0.8Mn0.1Co0.1)O2 |

| SOC | state of charge |

| UTM | universal testing machine |

| electrical potential |

References

- Cannarella, J.; Arnold, C.B. Stress evolution and capacity fade in constrained lithium-ion pouch cells. J. Power Sources 2014, 245, 745–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wünsch, M.; Kaufman, J.; Sauer, D.U. Investigation of the influence of different bracing of automotive pouch cells on cyclic liefetime and impedance spectra. J. Energy Storage 2019, 21, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, V.; Scurtu, R.G.; Richter, K.; Waldmann, T.; Memm, M.; Danzer, M.A.; Wohlfahrt-Mehrens, M. Effects of Mechanical Compression on the Aging and the Expansion Behavior of Si/C-Composite|NMC811 in Different Lithium-Ion Battery Cell Formats. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2019, 166, A3796–A3805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deich, T.; Storch, M.; Steiner, K.; Bund, A. Effects of module stiffness and initial compression on lithium-ion cell aging. J. Power Sources 2021, 506, 230163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daubinger, P.; Schelter, M.; Petersohn, R.; Nagler, F.; Hartmann, S.; Herrmann, M.; Giffin, G.A. Impact of Bracing on Large Format Prismatic Lithium–Ion Battery Cells during Aging. Adv. Energy Mater. 2022, 12, 2102448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aufschläger, A.; Kücher, S.; Kraft, L.; Spingler, F.; Niehoff, P.; Jossen, A. High precision measurement of reversible swelling and electrochemical performance of flexibly compressed 5 Ah NMC622/graphite lithium-ion pouch cells. J. Energy Storage 2023, 59, 106483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauerteig, D.; Hanselmann, N.; Arzberger, A.; Reinshagen, H.; Ivanov, S.; Bund, A. Electrochemical-mechanical coupled modeling and parameterization of swelling and ionic transport in lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2018, 378, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, D.J.; Fernandez, M.A.; Streng, K.C.; Hou, X.X.; Gao, X.; Weidner, J.W.; Garrick, T.R. Accounting for Non-Ideal, Lithiation-Based Active Material Volume Change in Mechano-Electrochemical Pouch Cell Simulation. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2020, 167, 080515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spingler, F.B.; Kücher, S.; Phillips, R.; Moyassari, E.; Jossen, A. Electrochemically Stable In Situ Dilatometry of NMC, NCA and Graphite Electrodes for Lithium-Ion Cells Compared to XRD Measurements. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2021, 168, 040515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Klinsmann, M.; Chumakov, S.; Li, X.; Kim, S.U.; Metzger, M.; Besli, M.M.; Klein, R.; Linder, C.; Christensen, J. A Modified Electrochemical Model to Account for Mechanical Effects Due to Lithium Intercalation and External Pressure. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2021, 168, 020533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegel, H.; von Kessel, O.; Heugel, P.; Deich, T.; Tübke, J.; Birke, K.P.; Sauer, D.U. Volume and thickness change of NMC811|SiOx-graphite large-format lithium-ion cells: From pouch cell to active material level. J. Power Sources 2022, 537, 231443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Kessel, O.; Hoehl, T.; Heugel, P.; Brauchle, F.; Vrankovic, D.; Birke, K.P. Electrochemical-Mechanical Parameterization and Modeling of Expansion, Pressure, and Porosity Evolution in NMC811|SiOx-Graphite Lithium-Ion Cells. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2023, 170, 090534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannala, S.; Movahedi, H.; Garrick, T.R.; Stefanopoulou, A.G.; Siegel, J.B. Consistently Tuned Battery Lifetime Predictive Model of Capacity Loss, Resistance Increase, and Irreversible Thickness Growth. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2024, 171, 010532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrick, T.R.; Koch, B.J.; Fernandez, M.A.; Efimoff, E.; Teel, H.; Jones, M.D.; Tu, M.; Shimpalee, S. Modeling Reversible Volume Change in Automotive Battery Cells with Porous Silicon Oxide-Graphite Composite Anodes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2024, 171, 103509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durdel, A.; Brehm, J.; Elender, V.; Bitschnau, L.; Aufschläger, A.; Altmann, M.; Kotter, P.; Jossen, A. Modeling Volume and Porosity Change of Lithium-Ion Cells Due to Lithium Intercalation and External Pressure. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2025, 172, 050508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomadam, P.M.; Weidner, J.W. Modeling Volume Changes in Porous Electrodes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2006, 153, A179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrick, T.R.; Kanneganti, K.; Huang, X.; Weidner, J.W. Modeling Volume Change due to Intercalation into Porous Electrodes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2014, 161, E3297–E3301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrick, T.R.; Huang, X.; Srinivasan, V.; Weidner, J.W. Modeling Volume Change in Dual Insertion Electrodes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2017, 164, E3552–E3558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrick, T.R.; Higa, K.; Wu, S.L.; Dai, Y.; Huang, X.; Srinivasan, V.; Weidner, J.W. Modeling Battery Performance Due to Intercalation Driven Volume Change in Porous Electrodes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2017, 164, E3592–E3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spingler, F.B.; Friedrich, S.; Kücher, S.; Schmid, S.; López-Cruz, D.; Jossen, A. The Effects of Non-Uniform Mechanical Compression of Lithium-Ion Cells on Local Current Densities and Lithium Plating. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2021, 168, 110515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kücher, S.; Durdel, A.; Schabenberger, T.; Spingler, F.B.; Reuter, L.; Jossen, A. Investigating the Impact of Various Binder Contents and Compression on Graphite Single-Electrode Dilatometry Measurements. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2025, 172, 020537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daubinger, P.; Ebert, F.; Hartmann, S.; Giffin, G.A. Impact of electrochemical and mechanical interactions on lithium-ion battery performance investigated by operando dilatometry. J. Power Sources 2021, 488, 229457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Guo, H.; Hector, L.G.; Timmons, A. Threefold Increase in the Young’s Modulus of Graphite Negative Electrode during Lithium Intercalation. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2010, 157, A558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Hector, L.G.; James, C.; Kim, K.J. Lithium Concentration Dependent Elastic Properties of Battery Electrode Materials from First Principles Calculations. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2014, 161, F3010–F3018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxisch, T.; Ceder, G. Elastic properties of olivine LixFePO4 from first principles. Phys. Rev. B 2006, 73, 174112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, K.; Cho, E. Intrinsic origin of intra-granular cracking in Ni-rich layered oxide cathode materials. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. PCCP 2018, 20, 9045–9052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Sun, H.; de Vasconcelos, L.S.; Zhao, K. Mechanical and Structural Degradation of LiNixMnyCozO2 Cathode in Li-Ion Batteries: An Experimental Study. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2017, 164, A3333–A3341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Wang, Y. In-situ measurements of mechanical property and stress evolution of commercial graphite electrode. Mater. Des. 2020, 194, 108887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Kim, C.; Yun, S. Effective modulus of graphite electrode in Li-ion battery by considering ion concentration, porosity, and binding energy during lithium intercalation. Mater. Lett. 2018, 224, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, V.; Scurtu, R.G.; Memm, M.; Danzer, M.A.; Wohlfahrt-Mehrens, M. Study of the influence of mechanical pressure on the performance and aging of Lithium-ion battery cells. J. Power Sources 2019, 440, 227148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schabenberger, T.; Kücher, S.; Aufschläger, A.; Jossen, A. Impact of applied and preceding pressure on performance and reversible swelling of lithium-ion pouch cells with varying microporous separators. J. Energy Storage 2024, 102, 113910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brehm, J.; Durdel, A.; Kussinger, T.; Kotter, P.; Altmann, M.; Jossen, A. Mechanical Characterization and Modeling of Large-Format Lithium-Ion Battery Cell Electrodes and Separators for Real Operating Scenarios. Batteries 2024, 10, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Liu, B.; Hu, D. State of Charge Dependent Mechanical Integrity Behavior of 18650 Lithium-ion Batteries. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 21829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, W.J.; Ali, M.Y.; Pan, J. Mechanical behavior of representative volume elements of lithium-ion battery cells under compressive loading conditions. J. Power Sources 2014, 245, 609–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedlatschek, T.; Krämer, M.; Gibson, J.S.L.; Korte-Kerzel, S.; Bezold, A.; Broeckmann, C. Mechanical properties of heterogeneous, porous LiFePO4 cathodes obtained using statistical nanoindentation and micromechanical simulations. J. Power Sources 2022, 539, 231565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linders, K.; Jenu, S.; Hentunen, A.; Chandra Mouli, G.R. The impact of V2X on battery degradation: A quantitative review. J. Power Sources 2025, 660, 238482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kücher, S.; Schabenberger, T.; Zonta, E.; Jossen, A. Performance and Properties of Laboratory and Commercial Separators under Compression and Varying Temperature. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2025, 172, 070512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Dang, D.; Li, D.; Hu, J.; Cheng, Y.T. Influence of polymeric binders on mechanical properties and microstructure evolution of silicon composite electrodes during electrochemical cycling. J. Power Sources 2019, 425, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Wiener, C.G.; Zhu, Y.; Vogt, B.D. Swelling and plasticization of polymeric binders by Li-containing carbonate electrolytes using quartz crystal microbalance with dissipation. Polymer 2018, 143, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäckel, N.; Dargel, V.; Shpigel, N.; Sigalov, S.; Levi, M.D.; Daikhin, L.; Aurbach, D.; Presser, V. In situ multi-length scale approach to understand the mechanics of soft and rigid binder in composite lithium ion battery electrodes. J. Power Sources 2017, 371, 162–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).