Resistance of Mulberry Fruit Sclerotiniosis Pathogens to Thiophanate-Methyl and Boscalid

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Tested Fungicides

2.2. Collection of Tested Isolates

2.3. Morphological Characterization

2.4. ITS Analysis

2.5. Determination of Resistance to Boscalid and Thiophanate-Methyl

2.6. Evaluation of Resistance Level

2.7. Analysis of Cross-Resistance

2.8. Evaluation of Effect of Temperature on the Growth

2.9. Analysis of Resistance Mechanisms

2.10. Molecular Docking

3. Results

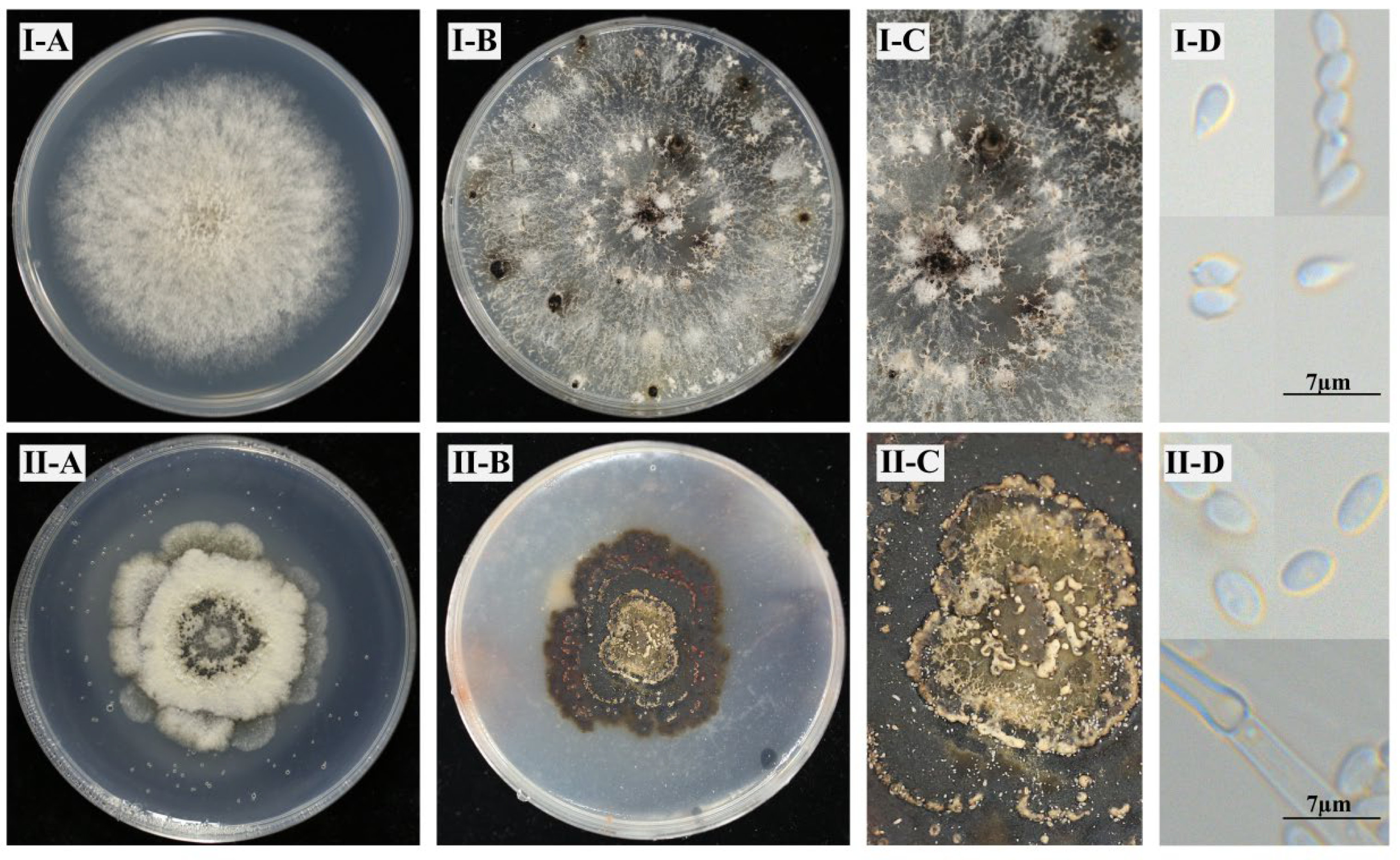

3.1. Morphological Characteristics

3.2. Phylogenetic Analysis

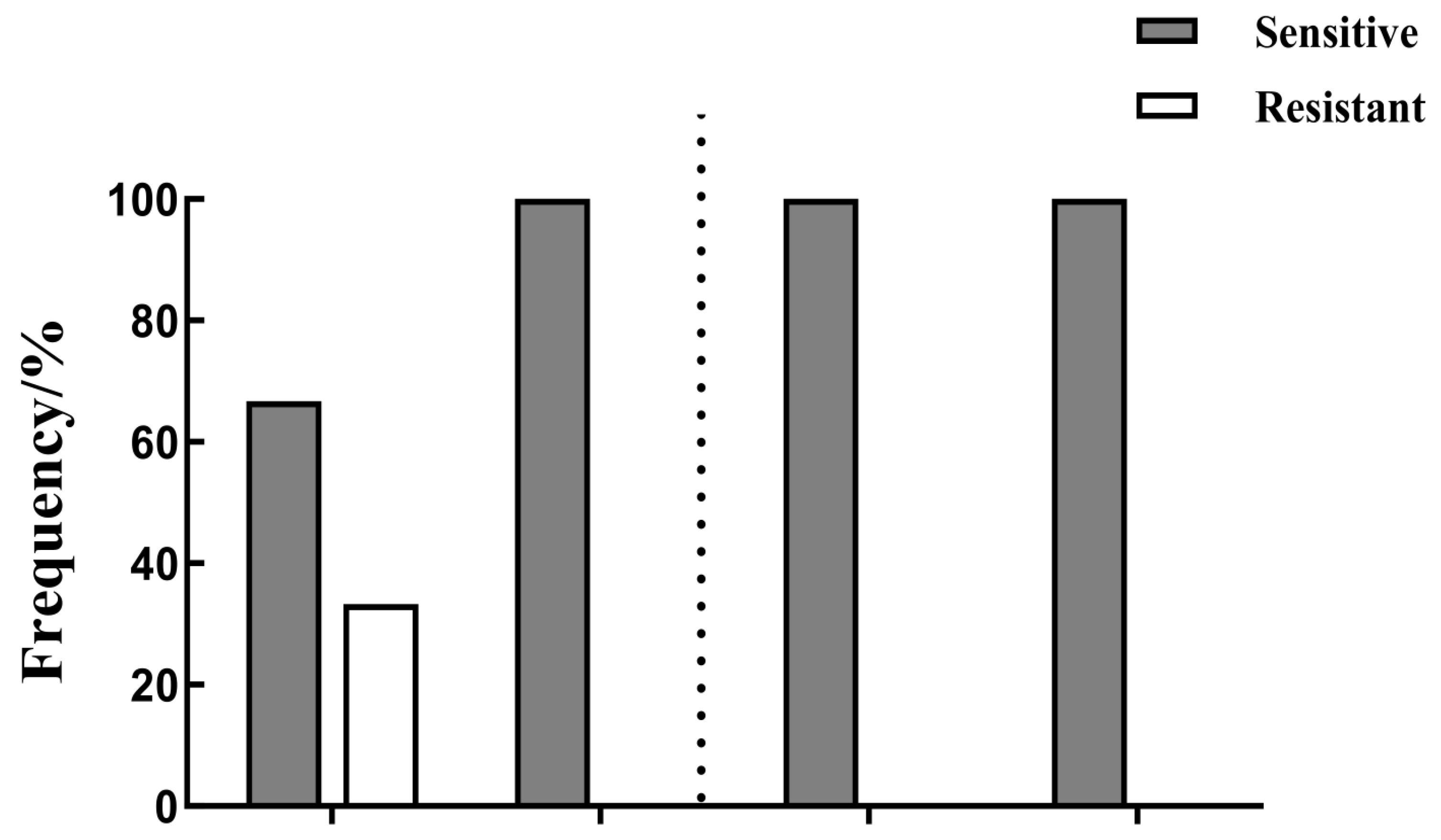

3.3. Sensitivity to Boscalid and Thiophanate-Methyl

3.4. Levels of Resistance to Thiophanate-Methyl

3.5. Cross-Resistance Between Thiophanate-Methyl and Other Fungicides

3.6. Effect of Temperature on Growth of ThR

3.7. Resistance Mechanisms

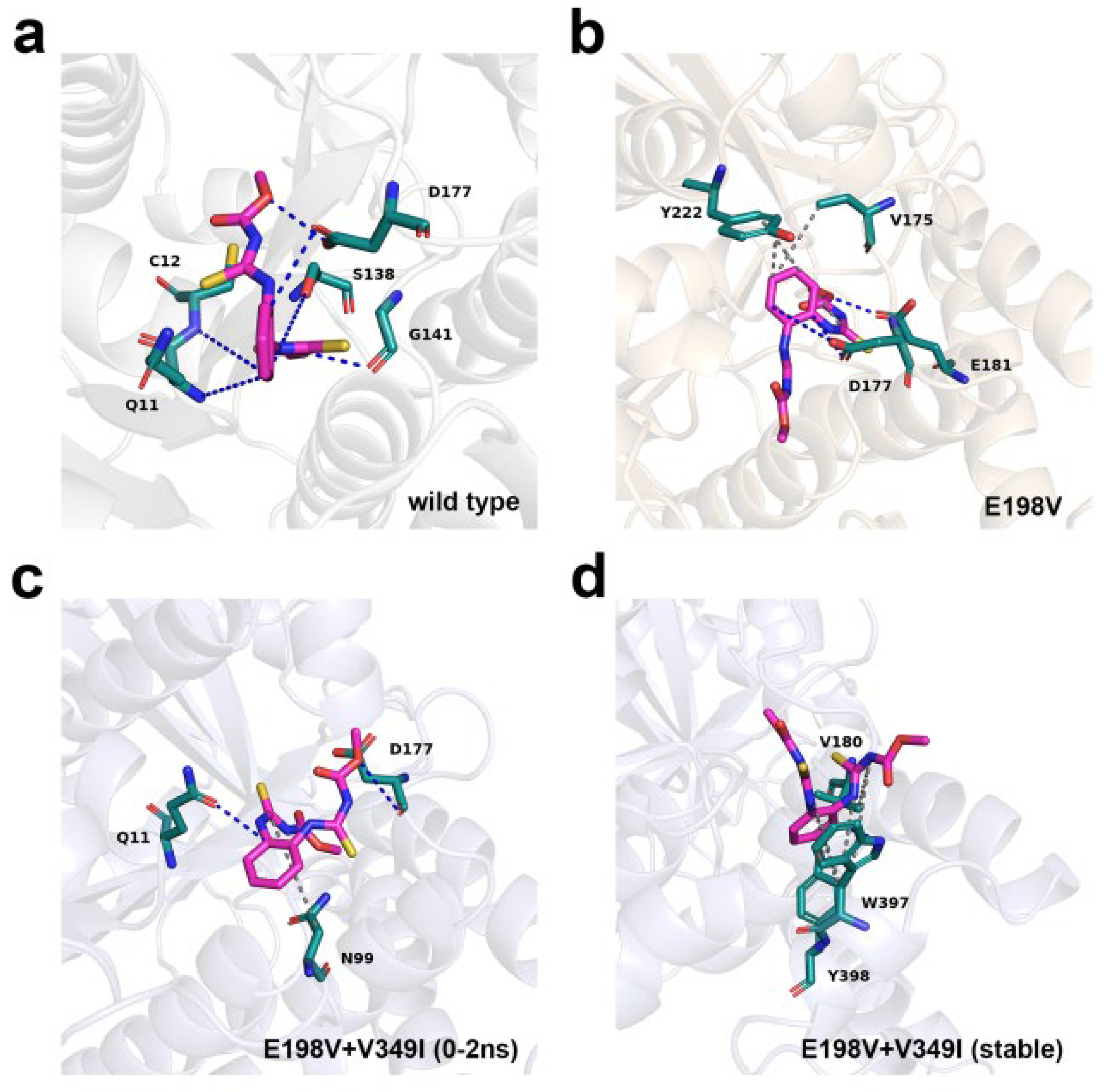

3.8. Binding Pattern of β-Tubulin

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lv, Z.Y.; Tian, L.C.; He, N.J. Research progress of mulberry sclerotial disease. Acta Phytopathol. Sin. 2023, 53, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.K.; Kim, W.G.; Sung, G.B.; Nam, S.H. Identification and distribution of two fungal species causing sclerotial disease on mulberry fruits in Korea. Mycobiology 2007, 35, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boland, G.J.; Hall, R. Index of plant hosts of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 1994, 16, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.Y.; He, Z.W.; Yuan, J.L.; Hao, L.J.; Song, Z.G.; Chen, G.K.; Ren, J.Q.; He, N.J. Investigation and rapid detection of fungal pathogens causing mulberry sclerotial disease in south-west China. Plant Pathol. 2022, 71, 684–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.X.; Yu, C.; Dong, Z.X.; Mo, R.L.; Zhang, C.; Liu, X.X.; Zuo, Y.Y.; Li, Y.; Deng, W.; Hu, X.M. Phylogeny and fungal community structures of helotiales associated with sclerotial disease of mulberry fruits in China. Plant Dis. 2024, 108, 502–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, F.F.; Li, X.L.; Wei, Z.X.; Han, G.H. The complete genome sequence of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (S1), one of the pathogens causing sclerotinosis in mulberry fruit. PhytoFrontiers 2024, 4, 416–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, W.K.; Kim, H.B.; Sung, G.B.; Li, Y.; Park, K.U.; Kim, Y.S. Mulberry popcorn disease occurrence in Korea region and development of integrative control method. Int. J. Indust. Entomol. 2016, 33, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.P.; Yu, S.F.; Liu, S.Y.; Ma, H.Y.; Shen, G.X.; Chen, L. A study on appropriate fungicide applying period and control methods against mulberry sclerotium disease. Acta Sericol. Sin. 2018, 44, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Hu, X.M.; Deng, W.; Li, Y.; Han, G.M.; Ye, C.H. Soil fungal community comparison of different mulberry genotypes and the relationship with mulberry fruit sclerotiniosis. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.P.; Tsuji, S.S.; Li, Y.; Hu, M.J.; Bandeira, M.A.; Câmara, M.P.S.; Micheref, S.J.; Schnabel, G. Reduced sensitivity of azoxystrobin and thiophanate-methyl resistance in Lasiodiplodia theobromae from papaya. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2020, 162, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petkar, A.; Langston, D.B.; Buck, J.W.; Stevenson, K.L.; Ji, P.S. Sensitivity of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. niveum to prothioconazole and thiophanate-methyl and gene mutation conferring resistance to thiophanate-methyl. Plant Dis. 2016, 101, 366–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Deng, S.J.; Gao, T.; Lamour, K.; Liu, X.L.; Ren, H.Y. Thiophanate-methyl resistance in Sclerotinia homoeocarpa from golf courses in China. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2018, 152, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, D.F.; Meng, H.; Lei, W.T.; Zheng, Y.L.; Li, L.H.; Wang, M.Y.; Zhong, R.; Wang, M.; Chen, F.P. Prevalence of H6Y mutation in β-tubulin causing thiophanate-methyl resistant in Monilinia fructicola from Fujian, China. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2022, 188, 105262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Duan, Y.B.; Wang, J.X.; Zhou, M.G. A new point mutation in the ironsulfur subunit of succinate dehydrogenase confers resistance to boscalid in Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2015, 16, 653–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vega, B.; Dewdney, M.M. Sensitivity of Alternaria alternata from citrus to boscalid and polymorphism in ironsulfur and in anchored membrane subunits of succinate dehydrogenase. Plant Dis. 2015, 99, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.M.; Li, J.; Ma, D.C.; Gao, Y.Y.; Cheng, J.G.; Mu, W.; Li, B.X.; Liu, F. SDH mutations confer complex cross-resistance patterns to SDHIs in Corynespora cassiicola. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2022, 186, 105157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Mao, Y.S.; Li, S.X.; Li, T.; Wang, J.X.; Zhou, M.G.; Duan, Y.B. Molecular Mechanism of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum Resistance to Succinate Dehydrogenase Inhibitor Fungicides. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 7039–7048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.N.; Ai, J.B.; Tang, A.M.; Wu, J.Y.; Zhang, C.Q. Identification of pathogenic fungi causing mulberry fruit sclerotiniose and their resistance to four fungicides in Zhejiang. J. Fruit Sci. 2020, 37, 1934–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.M.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.C.; He, S.; Zhu, F.X. Baseline sensitivity and toxic actions of boscalid against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Crop Prot. 2018, 110, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.B.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Pan, X.Y.; Wu, J.; Cai, Y.Q.; Li, T.; Zhao, D.L.; Wang, J.X.; Zhou, M.G. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification for the rapid detection of the F200Y mutant genotype of carbendazim-resistant isolates of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Plant Dis. 2016, 100, 976–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.X.; Zhang, L.; Wang, H.K.; Li, X.H.; Cheng, F.; Miao, J.Q.; Peng, Q.; Liu, X.L. Resistance to the DMI fungicide mefentrifluconazole in Monilinia fructicola: Risk assessment and resistance basis analysis. Pest Manag. Sci. 2024, 80, 1802–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Q.; Hao, X.C.; Liu, C.Y.; Li, X.H.; Lu, X.X.; Liu, X.L. Unveiling the resistance risk and resistance mechanism of florylpicoxamid in Corynespora cassiicola from cucumber. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2025, 208, 106228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eberhardt, J.; Santos-Martins, D.; Tillack, A.F.; Forli, S. AutoDock Vina 1.2.0: New docking methods, expanded force field, and python bindings. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021, 61, 3891–3898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanner, M.F. Python: A programming language for software integration and development. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 1999, 17, 57–61. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10660911/ (accessed on 17 December 2025).

- He, Z.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, F.C.; Liu, Y.; Wen, X.L.; Yu, C.; Cheng, X.K.; Li, D.C.; Huang, L.; Ai, H.; et al. Toxic effect of methyl-thiophanate on bombyx mori based on physiological and transcriptomic analysis. Genes 2024, 15, 1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorigan, A.F.; Moreira, S.I.; da Silva Costa Guimarães, S.; Cruz-Magalhães, V.; Alves, E. Target and non-target site mechanisms of fungicide resistance and their implications for the management of crop pathogens. Pest Manag. Sci. 2023, 79, 4731–4753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrea, E.; Katja, B.; Fernando, D.; May, M.; Carmen, C.; Marc, L.; Christian, N.; Jose, M.A.; Karl, H.A.; Michel, O. A new tubulin-binding site and pharmacophore for microtubule-destabilizing anticancer drugs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 13817–13821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.Q.; Hou, Y.; Wang, Q.C.; Lu, C.; Ma, X.C.; Wang, Z.S.; Xu, H.L. Analysis of the binding modes and resistance mechanism of four methyl benzimidazole carbamates inhibitors fungicides with Monilinia fructicola β2-tubulin protein. J. Mol. Struct. 2023, 1291, 136057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.M.; Zhao, Y.X. Interactions between benzimidazole fungicides and β2-tubulin of Fusarium graminearum. Mycosystema 2022, 41, 492–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Liu, X.; Schnabel, G. Field strains of Monilinia fructicola resistant to both MBC and DMI fungicides isolated from stone fruit orchards in the eastern United States. Plant Dis. 2013, 97, 1063–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, F.; Hamada, M.S.; Li, N.; Li, G.Q.; Luo, C.X. Multiple fungicide resistance in Botrytis cinerea from greenhouse strawberries in Hubei province, China. Plant Dis. 2017, 101, 601–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malandrakis, A.; Markoglou, A.; Ziogas, B. Molecular characterization of benzimidazole-resistant B. cinerea field isolates with reduced or enhanced sensitivity to zoxamide and diethofencarb. Pest Biochem. Physiol. 2011, 99, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banno, S.; Fukumori, F.; Ichiishi, A.; Okada, K.; Uekusa, H.; Kimura, M.; Fujimura, M. Genotyping of benzimidazole-resistant and dicarboximide-resistant mutations in Botrytis cinerea using real-time polymerase chain reaction assays. Phytopathology 2008, 98, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.H.; Li, D.L.; Zhu, W.; Wu, E.J.; Yang, L.N.; Wang, Y.P.; Waheed, A.; Zhan, J.S. Slow and temperature-mediated pathogen adaptation to a nonspecific fungicide in agricultural ecosystem. Evol. Appl. 2018, 11, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, F.; Li, X.B.; Yang, Y.Y.; Zhang, J.Y.; Zhu, Y.X.; Yin, W.X.; Li, G.Q.; Luo, C.X. Benzimidazole-resistant isolates with E198A/V/K mutations in the β-tubulin gene possess different fitness and competitive ability in Botrytis cinerea. Plant Dis. 2022, 112, 2321–2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, D.Y.; Li, F.J.; Zhang, Z.H.; Xu, Q.N.; Cao, Y.Y.; Jane, I.M.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Chen, C.J. Physiological and biochemical characteristics of boscalid resistant isolates of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum from asparagus lettuce. J. Integr. Agric. 2023, 22, 3694–3708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, D.Y.; Yuan, S.K.; Bi, Y.; Ma, C.Y. Sensitivity of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum on oilseed rape from three different regions of China to four fungicides. Plant Prot. 2025, 51, 354–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Isolate | Phenotype | EC50 (μg/mL) | Resistance Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| SS-1 | S * | 0.004 | - |

| SS-2 | S | 0.008 | - |

| SS-3 | S | 0.002 | - |

| SS-6 | S | 0.004 | - |

| SS-7 | S | 0.003 | - |

| SS-9 | S | 0.009 | - |

| SS-10 | S | 0.001 | - |

| SS-12 | S | 0.002 | - |

| SS-4 | R | 56.721 | 13,750.55 |

| SS-5 | R | 75.463 | 18,294.06 |

| SS-8 | R | 68.562 | 16,621.09 |

| SS-11 | R | 57.056 | 13,831.76 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, X.; Chen, T.; Zhang, Q.; Mao, C.; Zhang, C. Resistance of Mulberry Fruit Sclerotiniosis Pathogens to Thiophanate-Methyl and Boscalid. Horticulturae 2026, 12, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010009

Chen X, Chen T, Zhang Q, Mao C, Zhang C. Resistance of Mulberry Fruit Sclerotiniosis Pathogens to Thiophanate-Methyl and Boscalid. Horticulturae. 2026; 12(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Xiangmo, Tao Chen, Qianqian Zhang, Chengxin Mao, and Chuanqing Zhang. 2026. "Resistance of Mulberry Fruit Sclerotiniosis Pathogens to Thiophanate-Methyl and Boscalid" Horticulturae 12, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010009

APA StyleChen, X., Chen, T., Zhang, Q., Mao, C., & Zhang, C. (2026). Resistance of Mulberry Fruit Sclerotiniosis Pathogens to Thiophanate-Methyl and Boscalid. Horticulturae, 12(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010009