Effects of Aluminum Concentration and Application Period on Sepal Bluing and Growth of Hydrangea macrophylla

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

2.2. Aluminum Application Period and Concentration

2.3. Determination of Color Parameters

2.4. Determination of Total Anthocyanin Content

2.5. Measurement of Plant Trait Indicators

2.6. Measurement of SPAD Value

2.7. Determination of Nutrient Content

2.8. Determination of Total Nitrogen

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

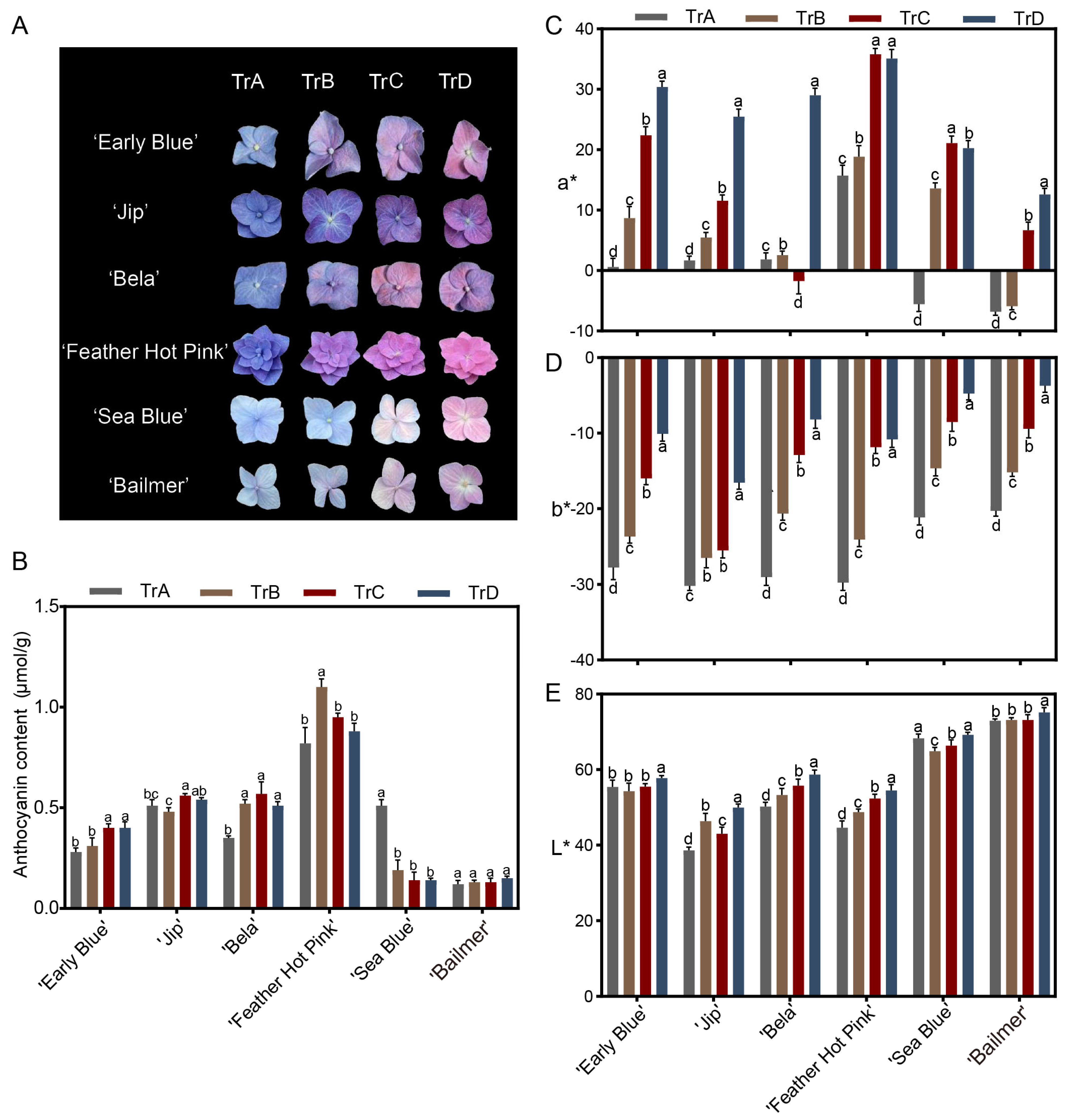

3.1. Effect of Aluminum Concentration on Sepal Color in H. macrophylla

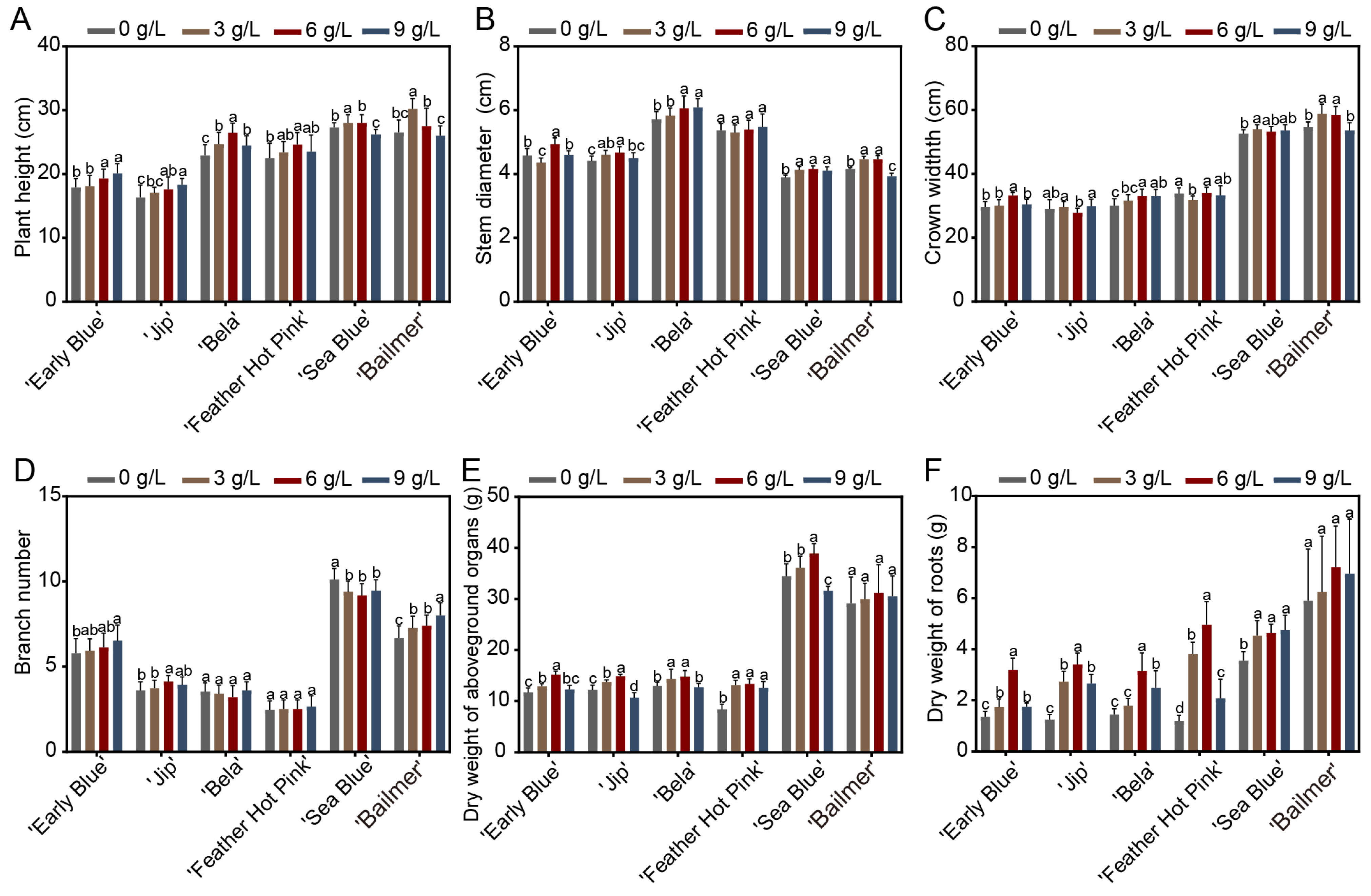

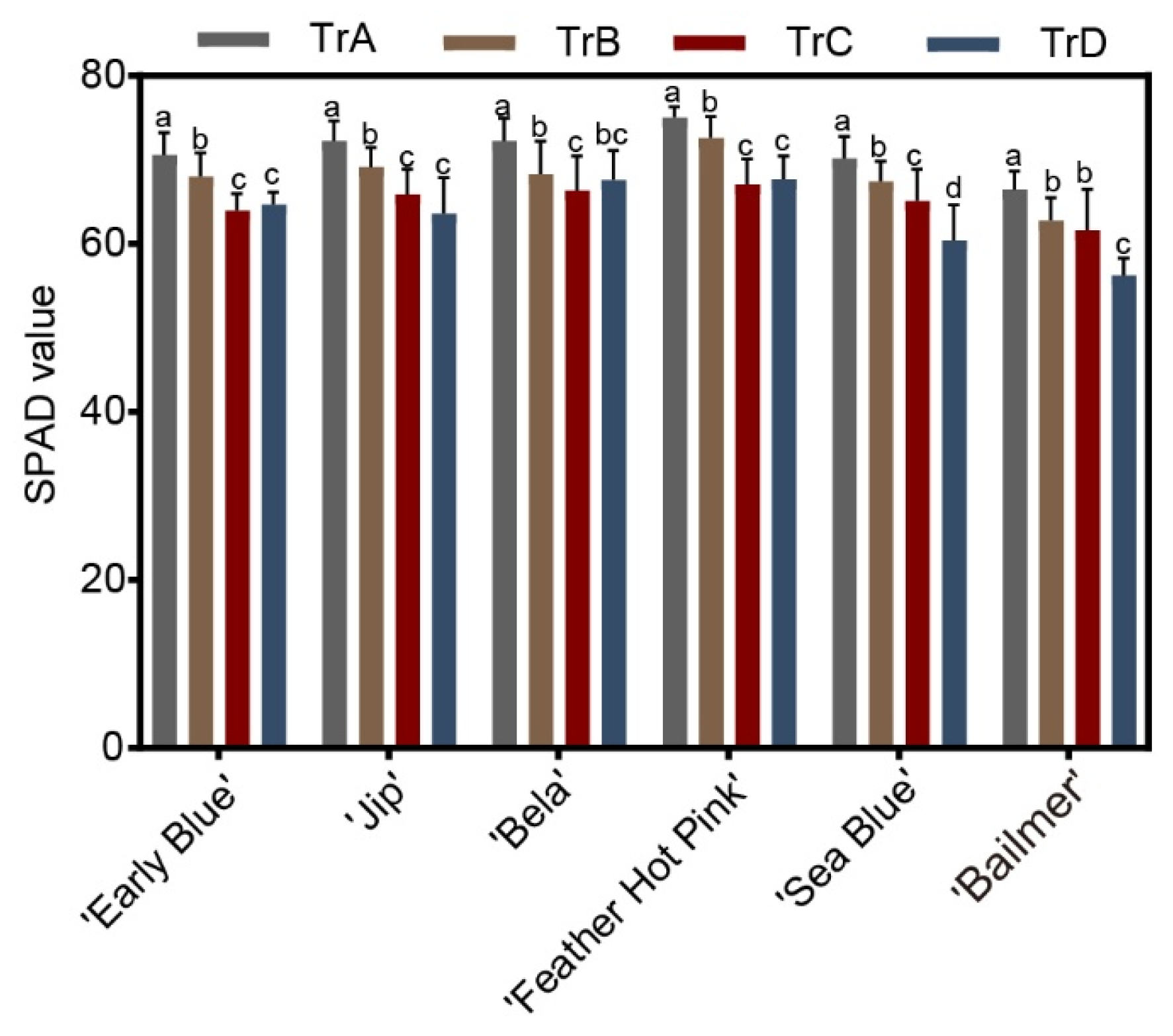

3.2. Effects of Different Aluminum Concentration on Phenotypic Traits and Relative Chlorophyll Content in H. macrophylla

3.3. The Influence of Aluminum on the Uptake of Nutrients by H. macrophylla

3.4. Impact of Aluminum Treatment at Different Developmental Periods on Sepal Color in H. macrophylla

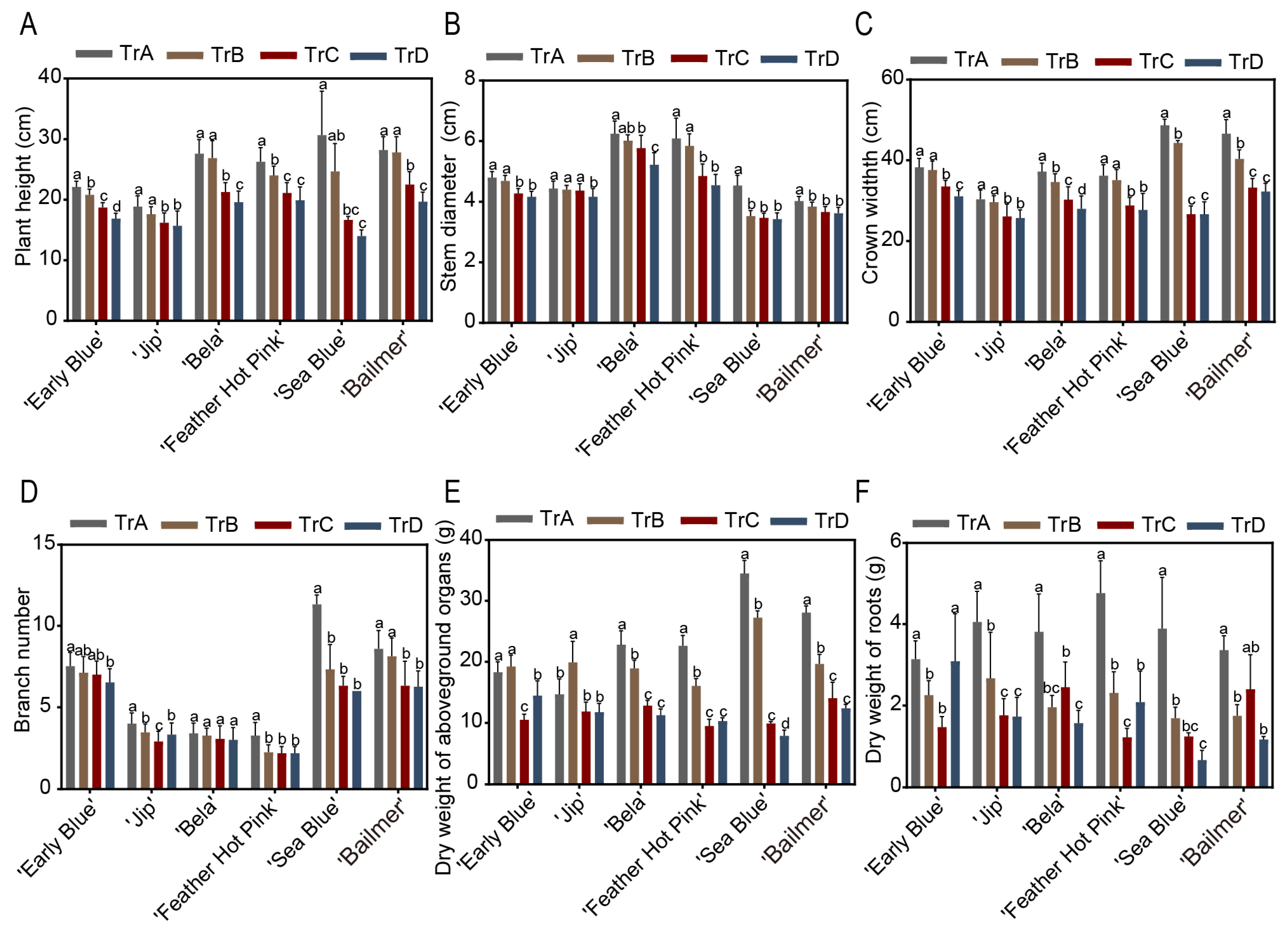

3.5. Effects of Different Aluminum Application Periods on Phenotypic Traits and Relative Chlorophyll Content of H. macrophylla

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu, X.; Simpson, S.A.; Youngblood, R.C.; Liu, X.F.; Scheffler, B.E.; Rinehart, T.A.; Alexander, L.W.; Hulse-Kemp, A.M. Two haplotype-resolved genomes reveal important flower traits in bigleaf hydrangea (Hydrangea macrophylla) and insights into Asterid evolution. Hortic. Res. 2023, 10, uhad217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Fan, Y.; Luo, S.; Liu, C.; Yuan, S. Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS) in Hydrangea macrophylla and Functional Analysis of HmF3′5′H. Plants 2024, 13, 3396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.; Yue, D.; Liang, Z.; Liu, C.; Yuan, S. Genome-Wide Identification of Expansin Gene Family and Its Association with Sepal Expansion During Flower Opening in Hydrangea macrophylla. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2025, 44, 5129–5146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, H.D.; Jones, A.H.; Lariviere, C.M.; Mayhew, K.M.; Cain, J.B. Role of aluminum in red-to-blue color changes in Hydrangea macrophylla sepals. Biometals 2011, 24, 1005–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, K.; Kariuda, M.; Itoi, H. Blueing of sepal colour of Hydrangea macrophylla. Phytochemistry 1985, 24, 2251–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, D.; Shinkai, Y.; Kato, Y.; Kondo, T.; Yoshida, K. Chemical studies on different color development in blue- and red-colored sepal cells of Hydrangea macrophylla. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2009, 73, 1054–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, T.; Oyama, K.I.; Yoshida, K. Direct Observation of Hydrangea Blue-Complex Composed of 3-O-Glucosyldelphinidin, Al3+ and 5-O-Acylquinic Acid by ESI-Mass Spectrometry. Molecules 2018, 23, 1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, K.; Oyama, K.I.; Kondo, T. Insight into chemical mechanisms of sepal color development and variation in hydrangea. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B Phys. Biol. Sci. 2021, 97, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Yuan, S.; Qi, H.; Chu, Z.; Liu, C. The Na+/H+ Exchanger NHX1 Controls H+ Accumulation in the Vacuole to Influence Sepal Color in Hydrangea macrophylla. Int. J. Plant Biol. 2023, 14, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Chen, W.; Liu, Y.; Ahmad, M.Z.; Feng, J.; Chen, H.; Qi, X.; Deng, Y. Overexpression of ATP binding cassette transporters (ABCs) from Hydrangea macrophylla enhance aluminum tolerance. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 495, 138988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.; Peng, A.; Li, Y.; Zuo, H.; Li, P.; Wang, J.; Yu, K.; Liu, C.; Zhao, S.; Wan, X.; et al. Tea plant roots respond to aluminum-induced mineral nutrient imbalances by transcriptional regulation of multiple cation and anion transporters. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ofoe, R.; Thomas, R.H.; Asiedu, S.K.; Wang-Pruski, G.; Fofana, B.; Abbey, L. Aluminum in plant: Benefits, toxicity and tolerance mechanisms. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1085998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.F.; Shi, Y.Z.; Lei, G.J.; Fry, S.C.; Zhang, B.C.; Zhou, Y.H.; Braam, J.; Jiang, T.; Xu, X.Y.; Mao, C.Z.; et al. XTH31, encoding an in vitro XEH/XET-active enzyme, regulates aluminum sensitivity by modulating in vivo XET action, cell wall xyloglucan content, and aluminum binding capacity in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 4731–4747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, P.; Han, D.; Chen, M.; Yang, L.; Li, Y.; Huang, T.; Xiong, W.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, X.; Wan, C.; et al. Overexpression of BnaXTH22 Improving Resistance to Aluminum Toxicity in Rapeseed (Brassica napus L.). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejia-Alvarado, F.S.; Botero-Rozo, D.; Araque, L.; Bayona, C.; Herrera-Corzo, M.; Montoya, C.; Ayala-Díaz, I.; Romero, H.M. Molecular network of the oil palm root response to aluminum stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Sánchez, V.; Tapia-Maruri, D.; Márquez-Guzmán, J.; Vázquez-Santana, S.; Cruz-Ortega, R. Role of cotyledons in aluminium accumulation as a tolerance strategy in Fagopyrum esculentum Moench (Polygonaceae) seedlings. Physiol. Plant. 2024, 176, e14554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustaka, J.; Ouzounidou, G.; Bayçu, G.; Moustakas, M. Aluminum resistance in wheat involves maintenance of leaf Ca2+ and Mg2+ content, decreased lipid peroxidation and Al accumulation, and low photosystem II excitation pressure. Biometals 2016, 29, 611–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, M.; Watanabe, T.; Jansen, S. The effects of aluminium on plant growth in a temperate and deciduous aluminium accumulating species. AoB Plants 2016, 8, plw065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Zhang, M.; Liu, X.; Mao, Q.; Shi, C.; Kochian, L.V.; Liao, H. Aluminium is essential for root growth and development of tea plants (Camellia sinensis). J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2020, 62, 984–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tao, J.; Cao, J.; Zeng, Y.; Li, X.; Ma, J.; Huang, Z.; Jiang, M.; Sun, L. The Beneficial Effects of Aluminum on the Plant Growth in Camellia japonica. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2020, 20, 1799–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, N.; Zvobgo, G.; Zhang, G.-p. A review: The beneficial effects and possible mechanisms of aluminum on plant growth in acidic soil. J. Integr. Agric. 2019, 18, 1518–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naumann, A.; Kunz, U.; Lehmann, H.; Stelzer, R.; Horst, W.J. Effect of aluminium on root morphology of Hydrangea macrophylla. In Plant Nutrition: Food Security and Sustainability of Agro-Ecosystems Through Basic and Applied Research; Horst, W.J., Schenk, M.K., Bürkert, A., Claassen, N., Flessa, H., Frommer, W.B., Goldbach, H., Olfs, H.W., Römheld, V., Sattelmacher, B., et al., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2001; pp. 516–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, K.; Yamashita, T.; Takahashi, A.; Timberlake, C.F. Stable blue complexes of anthocyanin-aluminium-3-p-coumaroyl- or 3-caffeoyl-quinic acid involved in the blueing of Hydrangea flower. Phytochemistry 1990, 29, 1089–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, S.; Wang, W.; Shen, T.; Li, X.; Kong, D.; Hou, X.; Chen, G.; Gao, L.; Xia, T.; Jiang, X. Crucial Role of Aluminium-Regulated Flavonol Glycosides (F2-Type) Biosynthesis in Lateral Root Formation of Camellia sinensis. Plant Cell Environ. 2025, 48, 3573–3589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Famoso, A.N.; Clark, R.T.; Shaff, J.E.; Craft, E.; McCouch, S.R.; Kochian, L.V. Development of a novel aluminum tolerance phenotyping platform used for comparisons of cereal aluminum tolerance and investigations into rice aluminum tolerance mechanisms. Plant Physiol. 2010, 153, 1678–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, H.; Hicks, K.; McCall, I.; Henry, J.B.; Whipker, B.E. Customizing the leaf tissue nutrient ranges for blue and pink hydrangeas. J. Plant Nutr. 2022, 45, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Yuan, S.; Qi, H.; Chu, Z.; Liu, C. Identification of Reliable Reference Genes for the Expression of Hydrangea macrophylla ‘Bailmer’ and ‘Duro’ Sepal Color. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Yu, R.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, X.; Gong, Z.; Qu, T. Metabolomics Combined with Transcriptomics Analysis Reveals the Regulation of Flavonoids in the Leaf Color Change of Acer truncatum Bunge. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makraki, T.; Tsaniklidis, G.; Papadimitriou, D.M.; Taheri-Garavand, A.; Fanourakis, D. Non-Destructive Monitoring of Postharvest Hydration in Cucumber Fruit Using Visible-Light Color Analysis and Machine-Learning Models. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Liu, C.; Fan, Y.; Yuan, S. Responses of Hydrangea macrophylla In Vitro Plantlets to Different Light Intensities. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Qi, X.; Feng, J.; Chen, H.; Qin, Z.; Wang, H.; Deng, Y. Biochemistry and transcriptome analyses reveal key genes and pathways involved in high-aluminum stress response and tolerance in hydrangea sepals. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 185, 268–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, T.; Aoki, D.; Fukushima, K.; Yoshida, K. Direct mapping of hydrangea blue-complex in sepal tissues of Hydrangea macrophylla. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, D.K.; Yadav, V.; Vaculík, M.; Gassmann, W.; Pike, S.; Arif, N.; Singh, V.P.; Deshmukh, R.; Sahi, S.; Tripathi, D.K. Aluminum toxicity and aluminum stress-induced physiological tolerance responses in higher plants. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2021, 41, 715–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowra, U.K.; Regon, P.; Kobayashi, Y.; Koyama, H.; Panda, S.K. Characterization of Al3+-toxicity responses and molecular mechanisms underlying organic acid efflux in Vigna mungo (L.) Hepper. Planta 2024, 260, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kochian, L.V.; Piñeros, M.A.; Liu, J.; Magalhaes, J.V. Plant Adaptation to Acid Soils: The Molecular Basis for Crop Aluminum Resistance. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2015, 66, 571–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, T.; Jansen, S.; Osaki, M. The beneficial effect of aluminium and the role of citrate in Al accumulation in Melastoma malabathricum. New Phytol. 2005, 165, 773–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, T.; Misawa, S.; Hiradate, S.; Osaki, M. Characterization of root mucilage from Melastoma malabathricum, with emphasis on its roles in aluminum accumulation. New Phytol. 2008, 178, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omenda, J.A.; Ngetich, K.F.; Kiboi, M.N.; Mucheru-Muna, M.W.; Mugendi, D.N. Phosphorus availability and exchangeable aluminum response to phosphate rock and organic inputs in the Central Highlands of Kenya. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhaes, J.V.; Piñeros, M.A.; Maciel, L.S.; Kochian, L.V. Emerging Pleiotropic Mechanisms Underlying Aluminum Resistance and Phosphorus Acquisition on Acidic Soils. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, J.; Keshavkant, S. Mechanisms underlying the phytotoxicity and genotoxicity of aluminum and their alleviation strategies: A review. Chemosphere 2021, 278, 130384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhao, X.Q.; Hu, Z.M.; Shao, J.F.; Che, J.; Chen, R.F.; Dong, X.Y.; Shen, R.F. Aluminium alleviates manganese toxicity to rice by decreasing root symplastic Mn uptake and reducing availability to shoots of Mn stored in roots. Ann. Bot. 2015, 116, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamaludin Alia, F.; Shamshuddin, J.; Fauziah, C.I.; Ahmad Husni, M.H.; Panhwar, Q.A. Effects of Aluminum, Iron and/or Low pH on Rice Seedlings Grown in Solution Culture. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2015, 17, 702–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, N.; Hafeez, M.B.; Shaukat, K.; Wahid, A.; Hasanuzzaman, M. Fe toxicity in plants: Impacts and remediation. Physiol. Plant. 2021, 173, 201–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Song, Y.; Fan, Z.; Ruan, J.; Hu, J.; Zhang, Q. Aluminum Supplementation Mediates the Changes in Tea Plant Growth and Metabolism in Response to Calcium Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 25, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinraide, T.B.; Ryan, P.R.; Kochian, L.V. Interactive effects of Al, h, and other cations on root elongation considered in terms of cell-surface electrical potential. Plant Physiol. 1992, 99, 1461–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.Q.; Shen, R.F.; Sun, Q.B. Ammonium under solution culture alleviates aluminum toxicity in rice and reduces aluminum accumulation in roots compared with nitrate. Plant Soil 2009, 315, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.Q.; Chen, R.F.; Shen, R.F. Coadaptation of Plants to Multiple Stresses in Acidic Soils. Soil Sci. 2014, 179, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhao, X.Q.; Chen, R.F.; Dong, X.Y.; Lan, P.; Ma, J.F.; Shen, R.F. Altered cell wall properties are responsible for ammonium-reduced aluminium accumulation in rice roots. Plant Cell Environ. 2015, 38, 1382–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.Q.; Shen, R.F. Aluminum-Nitrogen Interactions in the Soil-Plant System. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Cultivar | Treatment | N (g/kg) | P (g/kg) | K (g/kg) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aboveground Organs | Roots | Aboveground Organs | Roots | Aboveground Organs | Roots | ||

| ‘Early Blue’ | 0 g/L | 40.41 ± 0.24 c | 27.37 ± 0.17 d | 4.51 ± 0.18 a | 4.45 ± 0.05 a | 65.01 ± 1.75 b | 6.28 ± 0.25 c |

| 3 g/L | 43.69 ± 0.24 b | 27.96 ± 0.1 b | 4.03 ± 0.12 b | 3.4 ± 0.09 b | 65.24 ± 1.26 b | 12.57 ± 0.41 b | |

| 6 g/L | 44.73 ± 0.17 a | 30.67 ± 0.2 a | 3.66 ± 0.14 c | 3.12 ± 0.1 c | 64.9 ± 0.62 b | 19.32 ± 0.31 a | |

| 9 g/L | 44.44 ± 0.21 a | 28.21 ± 0.14 b | 3.51 ± 0.07 c | 2.63 ± 0.09 d | 69.25 ± 1.22 a | 5.37 ± 0.14 d | |

| ‘Jip’ | 0 g/L | 38.92 ± 0.21 d | 30.27 ± 0.18 c | 5.43 ± 0.05 a | 7.62 ± 0.16 a | 67.76 ± 0.75 a | 22.95 ± 0.44 a |

| 3 g/L | 43.43 ± 0.14 a | 34.3 ± 0.18 a | 4.16 ± 0.09 b | 6.3 ± 0.19 b | 67.52 ± 0.91 a | 6.86 ± 0.18 bc | |

| 6 g/L | 42.64 ± 0.17 b | 29.73 ± 0.14 d | 3.81 ± 0.08 c | 5.47 ± 0.16 c | 57.57 ± 0.69 c | 7.31 ± 0.1 b | |

| 9 g/L | 40.22 ± 0.13 c | 32.08 ± 0.21 b | 4.08 ± 0.15 b | 5.51 ± 0.22 c | 66.09 ± 0.33 b | 6.59 ± 0.28 c | |

| ‘Bela’ | 0 g/L | 37.44 ± 0.21 d | 28.07 ± 0.07 c | 5.49 ± 0.11 a | 5.81 ± 0.14 a | 59.44 ± 0.71 c | 6.17 ± 0.19 c |

| 3 g/L | 40.67 ± 0.1 c | 28.48 ± 0.21 b | 4.5 ± 0.07 b | 4.62 ± 0.12 c | 63.2 ± 0.7 b | 21.53 ± 0.35 b | |

| 6 g/L | 42.13 ± 0.17 a | 25.15 ± 0.2 d | 4.36 ± 0.11 b | 3.84 ± 0.14 d | 60.17 ± 0.55 c | 6.13 ± 0.09 c | |

| 9 g/L | 41.69 ± 0.27 b | 30.26 ± 0.21 a | 5.38 ± 0.07 a | 5.03 ± 0.11 b | 67.29 ± 1.07 a | 26.53 ± 0.42 a | |

| ‘Feather Hot Pink’ | 0 g/L | 39.55 ± 0.17 c | 29.47 ± 0.14 b | 5.9 ± 0.08 a | 6.8 ± 0.14 a | 61.17 ± 0.66 b | 7.4 ± 0.27 a |

| 3 g/L | 44.07 ± 0.14 a | 27.97 ± 0.17 c | 4.33 ± 0.14 b | 5.35 ± 0.2 b | 62.98 ± 0.83 a | 6.31 ± 0.21 b | |

| 6 g/L | 44.34 ± 0.24 a | 24.02 ± 0.24 d | 4.29 ± 0.07 b | 3.65 ± 0.12 d | 54.47 ± 1.12 c | 4.9 ± 0.11 c | |

| 9 g/L | 41.28 ± 0.14 b | 32.96 ± 0.17 a | 3.82 ± 0.1 c | 4.77 ± 0.11 c | 53.32 ± 1.06 c | 7.07 ± 0.25 a | |

| ‘Sea Blue’ | 0 g/L | 29.3 ± 0.14 b | 23.14 ± 0.14 b | 4.38 ± 0.1 a | 2.76 ± 0.05 b | 69.21 ± 0.63 b | 25.84 ± 0.57 a |

| 3 g/L | 28.37 ± 0.21 c | 23.97 ± 0.14 a | 3.86 ± 0.12 b | 2.48 ± 0.04 c | 72.3 ± 0.55 a | 13.8 ± 0.21 b | |

| 6 g/L | 30.64 ± 0.21 a | 23.28 ± 0.3 b | 3.57 ± 0.08 c | 2.43 ± 0.04 c | 64.98 ± 0.3 c | 13.08 ± 0.08 c | |

| 9 g/L | 24.27 ± 0.2 d | 21.77 ± 0.18 c | 2.94 ± 0.04 d | 3.12 ± 0.04 a | 57.12 ± 0.55 d | 12.78 ± 0.53 c | |

| ‘Bailmer’ | 0 g/L | 26.5 ± 0.17 b | 27.71 ± 0.14 b | 3.6 ± 0.09 a | 3.51 ± 0.09 a | 60.93 ± 0.95 c | 22.89 ± 0.36 a |

| 3 g/L | 28.48 ± 0.21 a | 25.91 ± 0.13 c | 3.32 ± 0.12 b | 2.95 ± 0.04 c | 63.4 ± 2.02 b | 15.5 ± 0.51 b | |

| 6 g/L | 28.3 ± 0.2 a | 25.79 ± 0.17 c | 3.01 ± 0.04 c | 2.26 ± 0.05 d | 66.36 ± 0.64 a | 11.87 ± 0.38 d | |

| 9 g/L | 17.56 ± 0.24 c | 28.14 ± 0.17 a | 3.03 ± 0.09 c | 3.31 ± 0.11 b | 65.7 ± 0.45 a | 13.9 ± 0.25 c | |

| Cultivar | Treatment | Ca (g/kg) | Mg (g/kg) | Fe (mg/g) | Mn (mg/kg) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aboveground Organs | Roots | Aboveground Organs | Roots | Aboveground Organs | Roots | Aboveground Organs | Roots | ||

| ‘Early Blue’ | 0 g/L | 1.7 ± 0.02 a | 1.81 ± 0.06 a | 4.42 ± 0.11 b | 2.21 ± 0.03 a | 302.79 ± 6.84 b | 680.17 ± 2.4 a | 92.5 ± 2.74 d | 112.77 ± 2.29 a |

| 3 g/L | 1.62 ± 0.03 b | 1.65 ± 0.07 b | 4.69 ± 0.12 b | 1.93 ± 0.04 b | 304.52 ± 5.08 b | 448.85 ± 3.17 c | 98.03 ± 2.8 c | 114.16 ± 2.63 a | |

| 6 g/L | 1.42 ± 0.03 c | 1.28 ± 0.01 c | 4.52 ± 0.11 b | 1.63 ± 0.03 c | 304.98 ± 4.32 b | 379.28 ± 12.09 d | 108.18 ± 2.9 b | 90.02 ± 1.65 b | |

| 9 g/L | 1.46 ± 0.06 c | 1.35 ± 0.04 c | 5.29 ± 0.21 a | 1.63 ± 0.03 c | 349.99 ± 7.42 a | 530.16 ± 9.89 b | 117.95 ± 3.1 a | 77.77 ± 2.66 c | |

| ‘Jip’ | 0 g/L | 1.9 ± 0.07 a | 1.76 ± 0.04 c | 3.94 ± 0.06 c | 1.87 ± 0.05 b | 312.95 ± 7.64 a | 834.65 ± 18.11 c | 109.46 ± 2.14 b | 118.47 ± 2.95 a |

| 3 g/L | 1.74 ± 0.05 b | 2.24 ± 0.06 b | 4.4 ± 0.06 b | 2.06 ± 0.09 a | 261.24 ± 7.44 c | 922.04 ± 22.49 b | 112.66 ± 2.25 b | 120.07 ± 0.92 a | |

| 6 g/L | 1.58 ± 0.02 c | 2.34 ± 0.1 b | 3.8 ± 0.1 c | 1.98 ± 0.04 a | 278.67 ± 4.72 b | 939.32 ± 17.7 b | 99.24 ± 2.5 c | 118.89 ± 2.14 a | |

| 9 g/L | 1.5 ± 0.02 c | 2.58 ± 0.07 a | 5.21 ± 0.19 a | 2 ± 0.03 a | 259.14 ± 1.54 c | 1043.75 ± 7.78 a | 128.89 ± 3.53 a | 116.38 ± 2.33 a | |

| ‘Bela’ | 0 g/L | 1.47 ± 0.03 a | 1.84 ± 0.04 a | 3.3 ± 0.05 c | 2.01 ± 0.06 a | 247.21 ± 3.83 c | 465.41 ± 13.13 c | 94.43 ± 1.15 c | 103.74 ± 2.35 a |

| 3 g/L | 1.53 ± 0.05 a | 1.7 ± 0.04 b | 3.7 ± 0.08 b | 1.67 ± 0.02 c | 302.39 ± 8.79 b | 417.78 ± 12.6 d | 105.19 ± 2.54 b | 105.4 ± 1.4 a | |

| 6 g/L | 1.3 ± 0.02 b | 1.52 ± 0.04 c | 3.66 ± 0.06 b | 1.54 ± 0.04 d | 232.17 ± 7.29 d | 683.1 ± 4.95 a | 106.01 ± 1.28 b | 82.31 ± 1.09 c | |

| 9 g/L | 1.48 ± 0.03 a | 1.73 ± 0.05 b | 4.83 ± 0.07 a | 1.84 ± 0.04 b | 336.12 ± 10.39 a | 511.54 ± 7.33 b | 128.49 ± 5.48 a | 86.39 ± 1.86 b | |

| ‘Feather Hot Pink’ | 0 g/L | 2.26 ± 0.03 a | 2.05 ± 0.03 a | 4.87 ± 0.14 b | 1.95 ± 0.03 a | 311.82 ± 5.26 b | 703.83 ± 15.81 c | 129.29 ± 1.84 a | 159.04 ± 3.62 a |

| 3 g/L | 1.99 ± 0.07 b | 2.05 ± 0.06 a | 5.57 ± 0.13 a | 1.98 ± 0.05 a | 540.39 ± 13.18 a | 804.43 ± 6.37 a | 129.19 ± 5.45 a | 139.01 ± 2.35 b | |

| 6 g/L | 1.63 ± 0.07 c | 1.54 ± 0.04 c | 4.95 ± 0.14 b | 1.56 ± 0.05 c | 298.23 ± 7.38 b | 775.25 ± 4.72 b | 109.01 ± 0.38 b | 97.78 ± 2.44 d | |

| 9 g/L | 1.5 ± 0.03 d | 1.83 ± 0.05 b | 4.46 ± 0.08 c | 1.74 ± 0.05 b | 313.51 ± 3 b | 659.79 ± 10.61 d | 102.26 ± 1.37 c | 113.46 ± 3.77 c | |

| ‘Sea Blue’ | 0 g/L | 1.61 ± 0.04 a | 2.43 ± 0.07 a | 4.14 ± 0.04 d | 2.1 ± 0.02 a | 215.85 ± 4.84 b | 775.64 ± 14.72 a | 88.38 ± 1.99 c | 70.56 ± 1.33 a |

| 3 g/L | 1.64 ± 0.03 a | 1.44 ± 0.04 b | 5.8 ± 0.09 a | 1.39 ± 0.03 c | 310.14 ± 6.93 a | 681.62 ± 4.06 c | 99.42 ± 2.16 a | 41.18 ± 0.88 d | |

| 6 g/L | 1.45 ± 0.02 c | 1.4 ± 0.06 b | 5.09 ± 0.08 b | 1.71 ± 0.05 b | 315.25 ± 7.11 a | 684.34 ± 5.07 c | 92.84 ± 1.38 b | 52.65 ± 2.16 b | |

| 9 g/L | 1.21 ± 0.05 c | 1.15 ± 0.02 c | 4.45 ± 0.06 c | 1.34 ± 0.03 c | 163.47 ± 3.14 c | 708.76 ± 8.86 b | 81.46 ± 2.28 d | 47.14 ± 1.68 c | |

| ‘Bailmer’ | 0 g/L | 1.42 ± 0.02 a | 1.42 ± 0.03 b | 2.98 ± 0.05 d | 2.47 ± 0.03 a | 175.95 ± 2.69 c | 426.6 ± 7.88 c | 59.19 ± 0.29 c | 70.53 ± 0.68 a |

| 3 g/L | 1.41 ± 0.04 a | 1.53 ± 0.04 a | 3.13 ± 0.03 c | 2.39 ± 0.05 a | 208.7 ± 3.73 b | 566.16 ± 9.05 a | 78.95 ± 1.78 b | 70.41 ± 0.86 a | |

| 6 g/L | 1.44 ± 0.04 a | 1.28 ± 0.04 c | 3.28 ± 0.05 b | 1.91 ± 0.07 c | 237.75 ± 2.96 a | 563.77 ± 9.55 a | 87.83 ± 1.53 a | 54.64 ± 0.28 c | |

| 9 g/L | 1.28 ± 0.02 b | 1.34 ± 0.03 c | 3.4 ± 0.05 a | 2.21 ± 0.05 b | 242.73 ± 3.74 a | 506.26 ± 2.59 b | 85.42 ± 2.17 a | 65.95 ± 1.83 b | |

| Cultivar | Treatment | Cu (mg/kg) | Zn (mg/kg) | Co (mg/kg) | B (mg/kg) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aboveground Organs | Roots | Aboveground Organs | Roots | Aboveground Organs | Roots | Aboveground Organs | Roots | ||

| ‘Early Blue’ | 0 g/L | 9.97 ± 0.23 b | 29.48 ± 1.26 a | 44.47 ± 2.09 d | 73.35 ± 1.63 d | 51.14 ± 2.21 c | 41.11 ± 0.92 c | 49.01 ± 1.25 b | 11.6 ± 0.26 b |

| 3 g/L | 9.32 ± 0.41 b | 25.95 ± 0.99 b | 70.14 ± 1.24 a | 98.06 ± 2.67 a | 66.97 ± 1.36 a | 56.18 ± 1.35 a | 52.06 ± 1.29 a | 13.65 ± 0.1 a | |

| 6 g/L | 18.4 ± 0.59 a | 18.86 ± 0.43 c | 58.49 ± 1.19 b | 93.89 ± 1.81 b | 52.55 ± 1.39 c | 53.49 ± 0.73 b | 47.79 ± 0.86 b | 13.39 ± 0.11 a | |

| 9 g/L | 9.73 ± 0.41 b | 20.43 ± 0.46 c | 54.25 ± 1.63 c | 82.24 ± 1.55 c | 59.16 ± 1.87 b | 30.42 ± 0.78 d | 52.85 ± 1.21 a | 10.74 ± 0.18 c | |

| ‘Jip’ | 0 g/L | 9.91 ± 0.26 c | 24.03 ± 0.54 b | 59.33 ± 0.76 b | 97.1 ± 1.2 c | 58.35 ± 0.75 c | 66.74 ± 1.74 d | 48.44 ± 0.55 c | 18.66 ± 0.35 a |

| 3 g/L | 10.61 ± 0.18 b | 26.01 ± 0.83 a | 62.69 ± 2.33 b | 94.11 ± 2.25 c | 67.11 ± 1.98 b | 76.14 ± 0.77 c | 59.4 ± 0.53 a | 14.72 ± 0.39 b | |

| 6 g/L | 12.44 ± 0.33 a | 26.03 ± 0.51 a | 53.57 ± 0.98 c | 106.27 ± 2.03 b | 87.52 ± 1.51 a | 87.95 ± 2.56 b | 33.14 ± 0.57 d | 14.44 ± 0.58 b | |

| 9 g/L | 9.14 ± 0.19 d | 22.26 ± 0.82 c | 67.05 ± 2.66 a | 123.59 ± 4.33 a | 49.14 ± 0.46 d | 118.11 ± 3.58 a | 53.66 ± 1.14 b | 14.86 ± 0.12 b | |

| ‘Bela’ | 0 g/L | 9.24 ± 0.29 c | 33.76 ± 0.59 b | 52.66 ± 0.66 d | 63.91 ± 1.72 c | 48.55 ± 1.1 c | 129.03 ± 3.26 a | 43.99 ± 1.21 c | 14.09 ± 0.27 b |

| 3 g/L | 9.75 ± 0.18 b | 23.91 ± 0.55 d | 60.58 ± 1.56 c | 70.16 ± 3.2 b | 77.75 ± 2.31 a | 116.83 ± 1.48 c | 52.18 ± 0.17 b | 15.07 ± 0.47 a | |

| 6 g/L | 8.97 ± 0.05 c | 37.92 ± 0.97 a | 65.26 ± 0.63 b | 67.73 ± 2.24 b | 48.66 ± 1.54 c | 70.75 ± 2.45 d | 45.14 ± 0.99 c | 12.13 ± 0.26 c | |

| 9 g/L | 12.27 ± 0.33 a | 25.47 ± 0.52 c | 72.66 ± 1.42 a | 75.38 ± 2.52 a | 72.79 ± 1.27 b | 122.2 ± 3.55 b | 59.12 ± 0.27 a | 13.79 ± 0.31 b | |

| ‘Feather Hot Pink’ | 0 g/L | 11.34 ± 0.22 a | 35.48 ± 0.63 a | 85.35 ± 2.14 b | 93.33 ± 3.05 a | 68.76 ± 1.01 a | 125.51 ± 4.82 a | 63.57 ± 1.93 a | 16.25 ± 0.31 a |

| 3 g/L | 8.97 ± 0.21 b | 34.75 ± 1.04 a | 64.8 ± 2.08 d | 81.58 ± 1.97 b | 63.08 ± 1.45 b | 108.02 ± 2.27 b | 66.38 ± 1.03 a | 12.28 ± 0.36 c | |

| 6 g/L | 8.23 ± 0.2 c | 27.29 ± 0.74 b | 73.85 ± 1.25 c | 71.75 ± 1.95 c | 48.52 ± 1.07 c | 58.53 ± 1.1 d | 54.71 ± 1.56 b | 9.83 ± 0.28 d | |

| 9 g/L | 11.48 ± 0.31 a | 24.75 ± 0.22 c | 133.08 ± 3.01 a | 85.01 ± 1.65 b | 40.39 ± 0.85 d | 71.98 ± 1.57 c | 52.15 ± 1.33 b | 13.01 ± 0.09 b | |

| ‘Sea Blue’ | 0 g/L | 9.09 ± 0.18 c | 24.24 ± 0.44 a | 50.77 ± 1.33 c | 40.36 ± 1.63 c | 59.77 ± 0.8 c | 92.37 ± 2.36 a | 36.73 ± 1.26 a | 12.03 ± 0.4 a |

| 3 g/L | 9.67 ± 0.26 b | 17.58 ± 0.25 c | 54.43 ± 0.64 b | 40.45 ± 0.66 c | 97.91 ± 0.24 a | 30.46 ± 0.63 d | 37.91 ± 0.78 a | 8.62 ± 0.2 d | |

| 6 g/L | 13.45 ± 0.44 a | 23.05 ± 0.53 b | 65.17 ± 0.92 a | 64.4 ± 2.04 a | 72.95 ± 2.08 b | 67.8 ± 1.67 b | 32.4 ± 0.42 b | 9.75 ± 0.27 c | |

| 9 g/L | 6.15 ± 0.31 d | 24.13 ± 0.35 a | 29.66 ± 0.39 d | 57.06 ± 1.06 b | 44.28 ± 1.07 d | 57.55 ± 1.59 c | 30.09 ± 0.7 c | 10.98 ± 0.19 b | |

| ‘Bailmer’ | 0 g/L | 10.97 ± 0.18 a | 21.77 ± 0.46 c | 42 ± 0.51 c | 84.54 ± 1.72 c | 63.58 ± 1.09 b | 62.61 ± 0.82 c | 38.56 ± 1.15 ab | 10.92 ± 0.41 a |

| 3 g/L | 7.76 ± 0.27 c | 31.25 ± 0.29 a | 33.03 ± 0.89 d | 70.53 ± 1.62 d | 55.06 ± 1.27 c | 70.89 ± 2.12 c | 39.1 ± 1.14 a | 10.84 ± 0.31 a | |

| 6 g/L | 9.92 ± 0.23 b | 25.21 ± 0.39 b | 47.84 ± 1.09 a | 119.59 ± 2.4 a | 71.93 ± 3.02 a | 70.44 ± 1.48 b | 35.67 ± 1.33 c | 10.55 ± 0.22 ab | |

| 9 g/L | 10.17 ± 0.3 b | 24.71 ± 0.54 b | 44.04 ± 1.09 b | 92.13 ± 1.89 b | 64.34 ± 1.74 b | 109.97 ± 2.91 a | 37.43 ± 1.48 abc | 10.04 ± 0.39 b | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Liang, Z.; Liu, C.; Fan, Y.; Yuan, S. Effects of Aluminum Concentration and Application Period on Sepal Bluing and Growth of Hydrangea macrophylla. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1490. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121490

Wang Y, Liang Z, Liu C, Fan Y, Yuan S. Effects of Aluminum Concentration and Application Period on Sepal Bluing and Growth of Hydrangea macrophylla. Horticulturae. 2025; 11(12):1490. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121490

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yaxin, Zhongshuo Liang, Chun Liu, Youwei Fan, and Suxia Yuan. 2025. "Effects of Aluminum Concentration and Application Period on Sepal Bluing and Growth of Hydrangea macrophylla" Horticulturae 11, no. 12: 1490. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121490

APA StyleWang, Y., Liang, Z., Liu, C., Fan, Y., & Yuan, S. (2025). Effects of Aluminum Concentration and Application Period on Sepal Bluing and Growth of Hydrangea macrophylla. Horticulturae, 11(12), 1490. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121490