Multicharacteristic Selection of Purple-Flesh Sweetpotato Genotypes with High Productivity and Anthocyanin Content

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Location of the Experiments and Plant Material

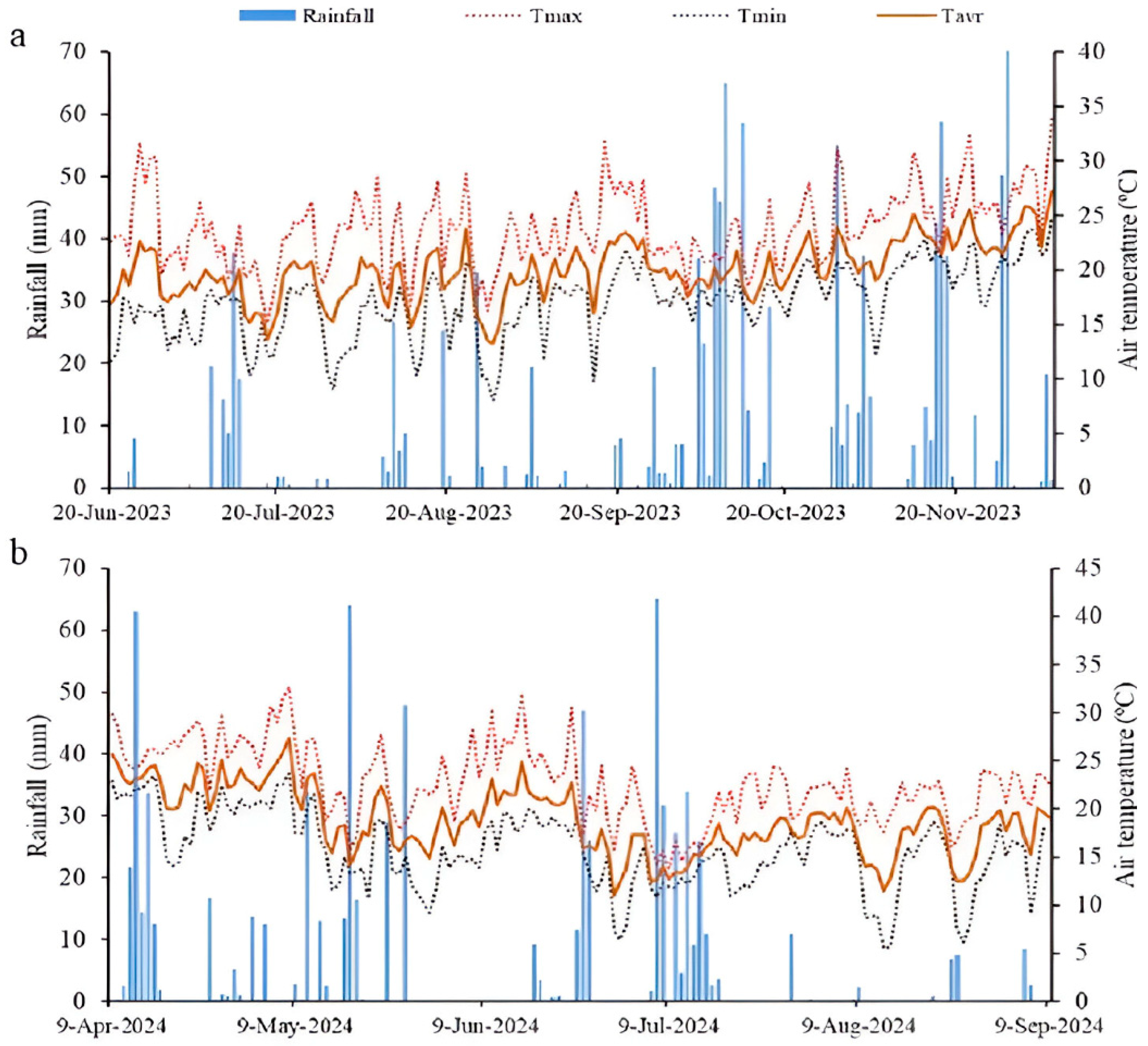

2.2. Meteorological Conditions During the Experimental Trials

2.3. Stage I: Genotype Pre-Selection

2.4. Agronomic Traits Stage I

2.5. Stage II: Evaluation and Selection of Superior Genotypes

2.6. Agronomic Traits Stage II

2.7. Postharvest Quality Characteristics

2.8. Statistical Analysis

2.8.1. Values Used in MGIDI for Characteristics in Stage I

2.8.2. Values Used in MGIDI for Characteristics in Stage II

3. Results

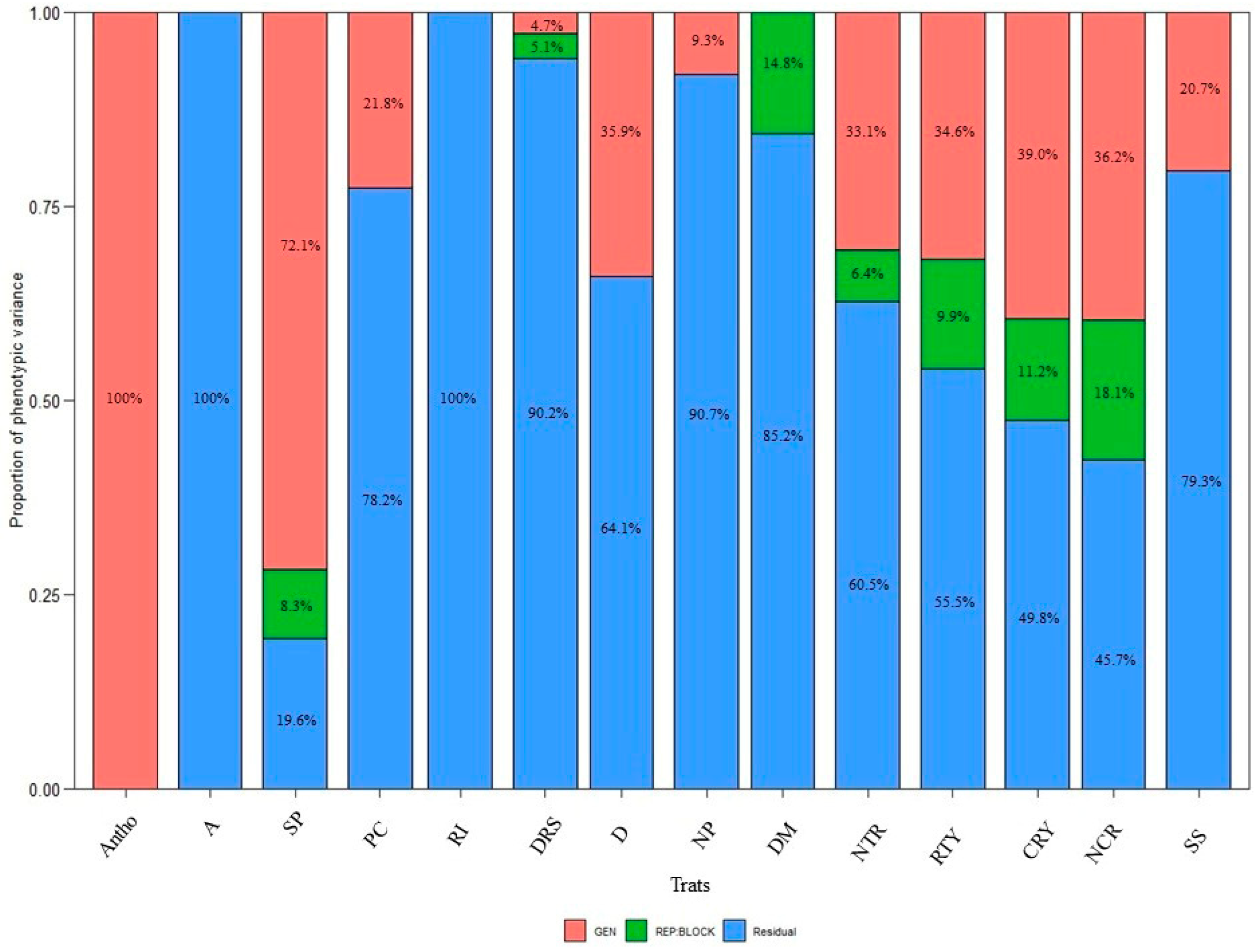

3.1. Stage I: Genotype Pre-Selection

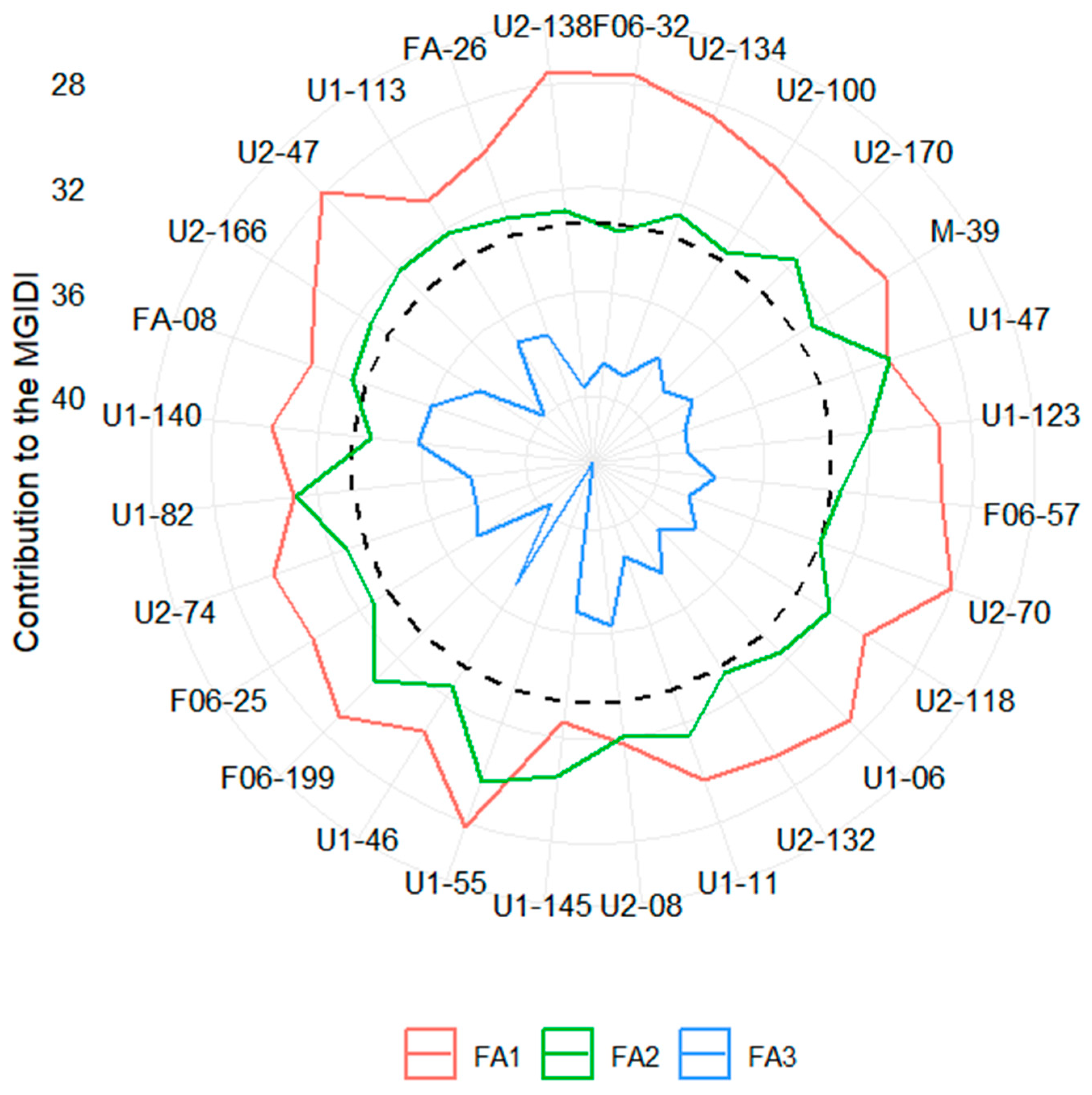

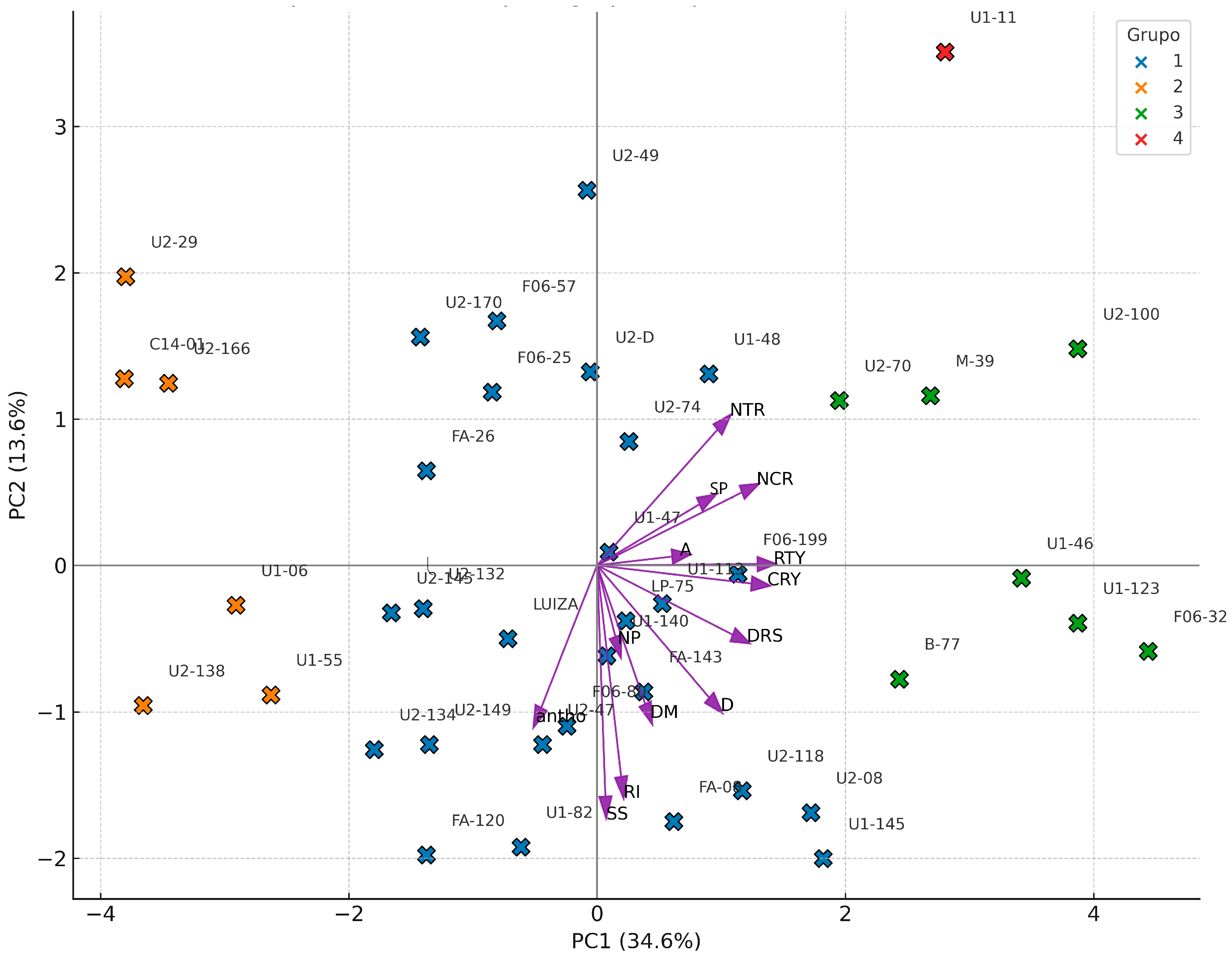

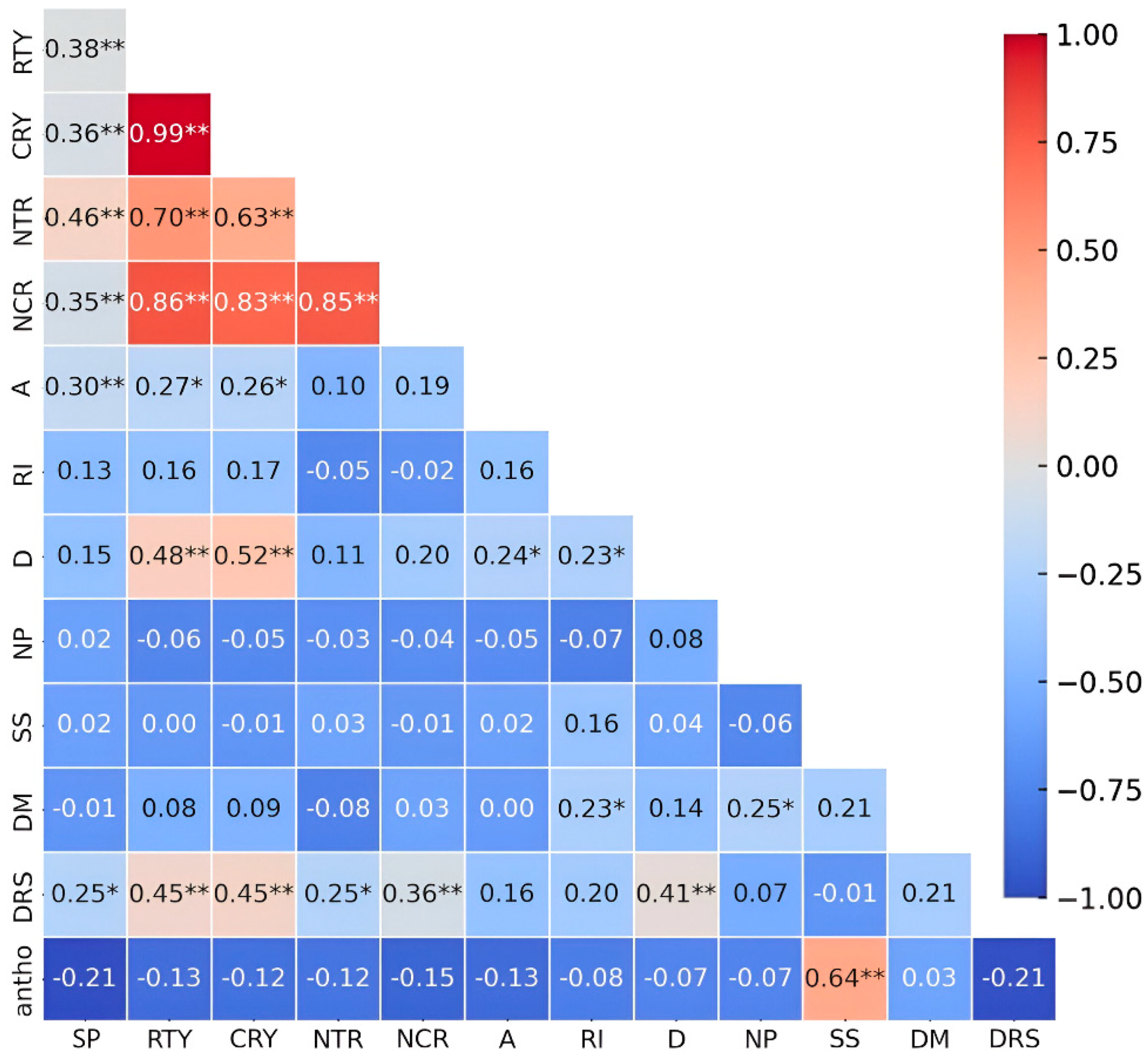

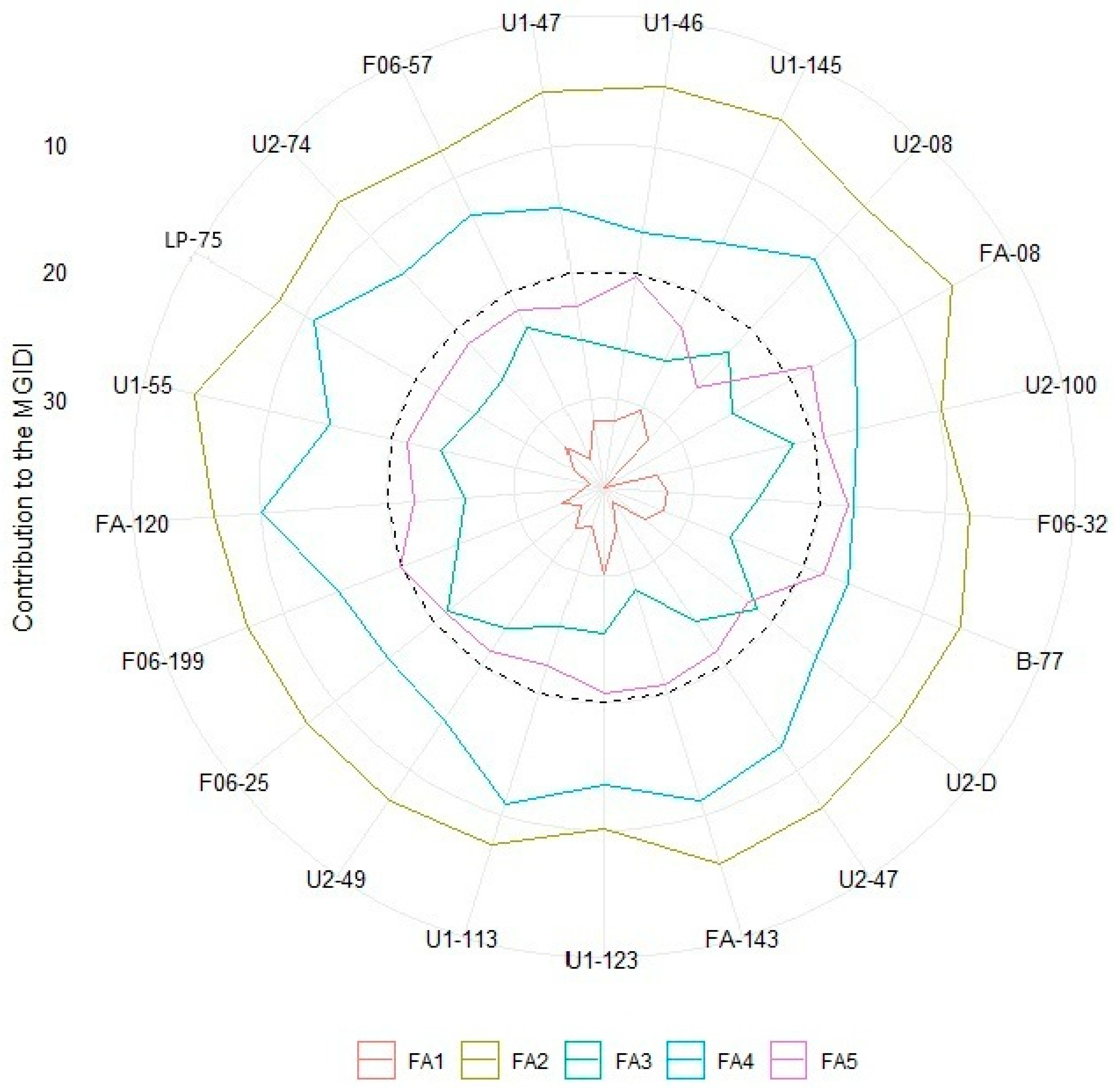

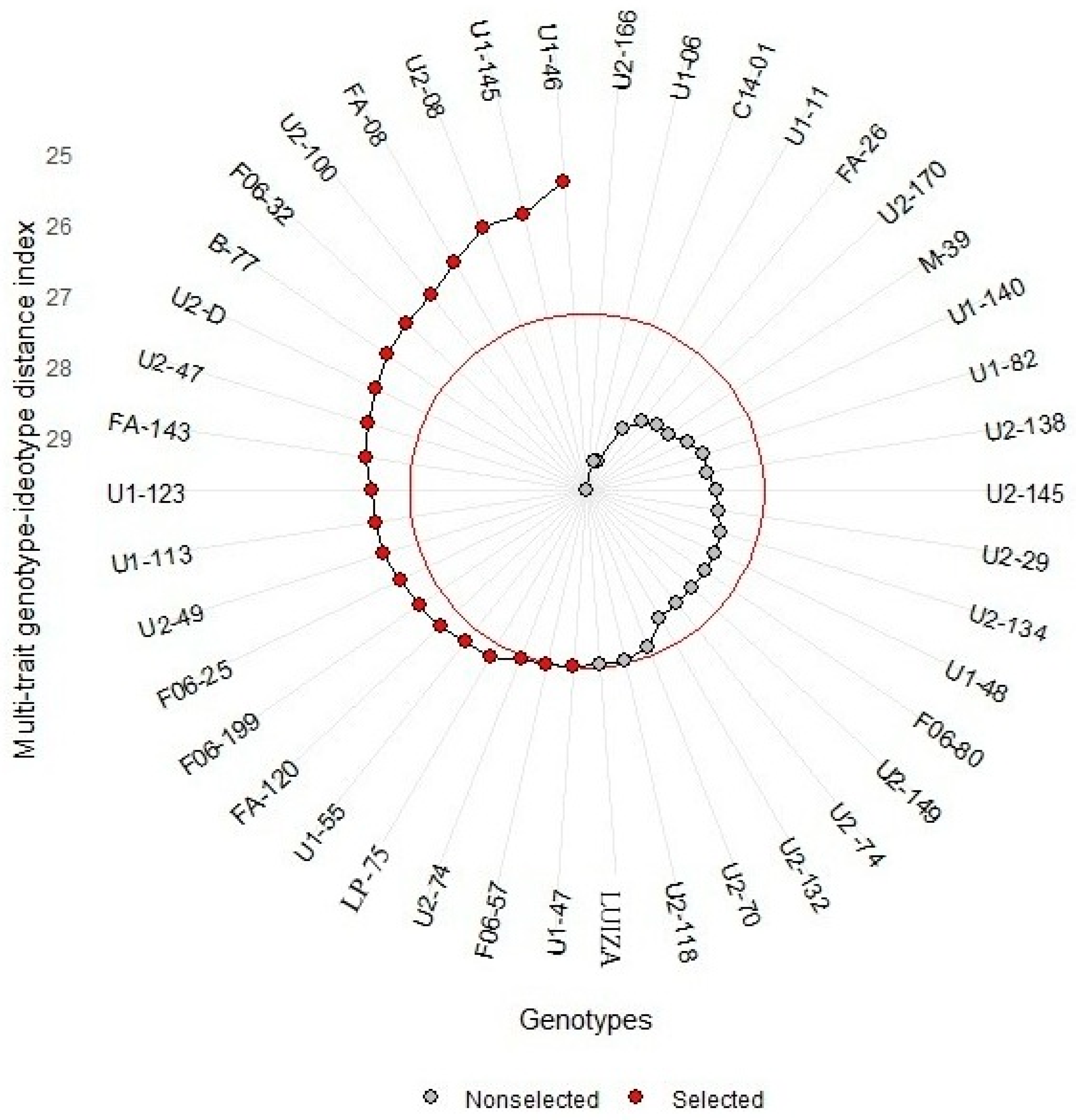

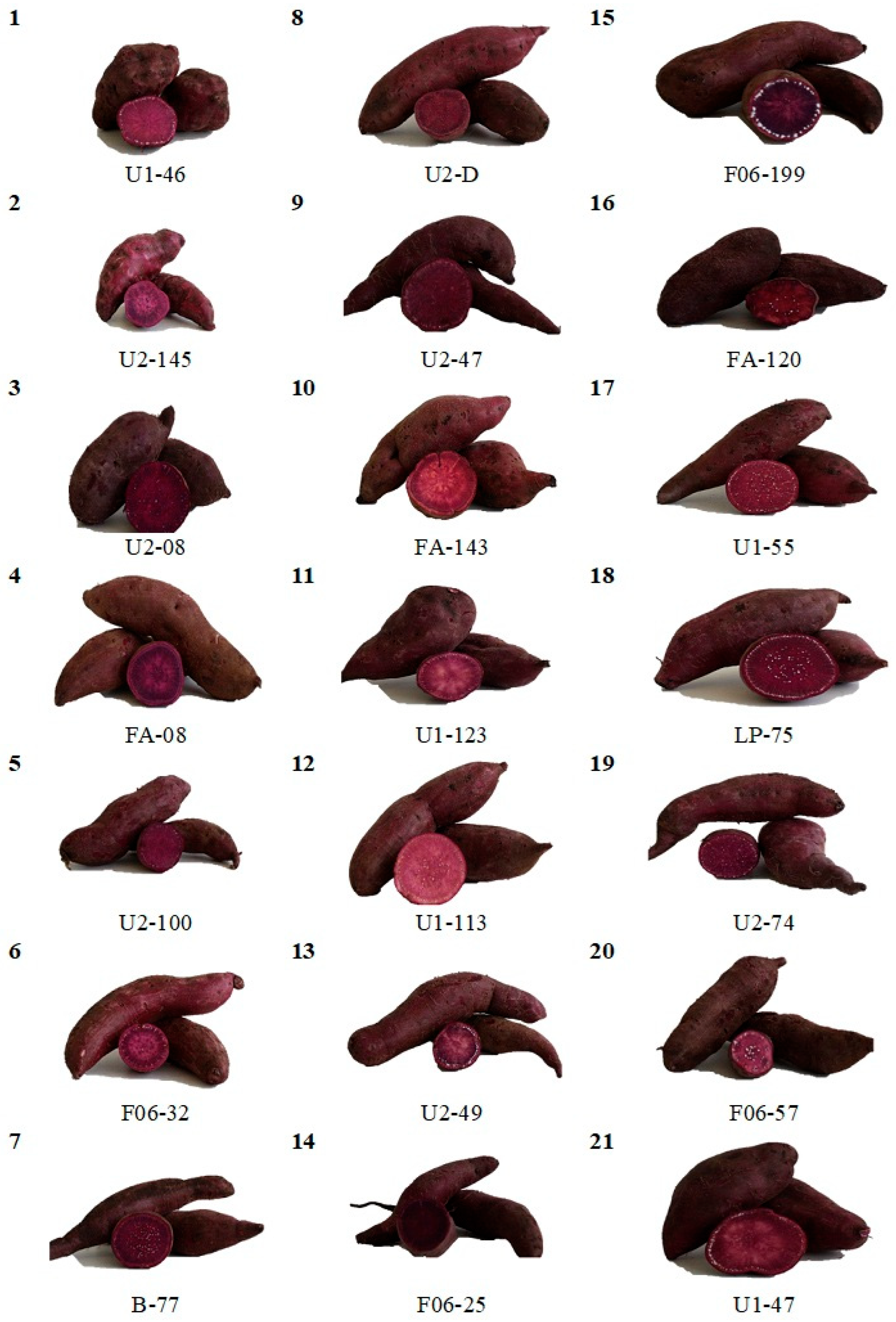

3.2. Stage II: Final Selection of Genotypes Based on Productivity and Anthocyanin Content

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Galvao, A.C.; Nicoletto, C.; Zanin, G.; Vargas, P.F.; Sambo, P. Nutraceutical Content and Daily Value Contribution of Sweet Potato Accessions for the European Market. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.B.; Warkentin, T.D. Biofortification of Pulse Crops: Status and Future Perspectives. Plants 2020, 9, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaliwal, S.S.; Sharma, V.; Shukla, A.K.; Verma, V.; Kaur, M.; Shivay, Y.S.; Nisar, S.; Gaber, A.; Brestic, M.; Barek, V.; et al. Biofortification—A Frontier Novel Approach to Enrich Micronutrients in Field Crops to Encounter the Nutritional Security. Molecules 2022, 27, 1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, M.P.; da Cunha, L.R.; Nastaro, B.T.; dos Santos Pereira, K.Y.; de Lima Nepomoceno, M. Biofortificação de alimentos: Problema ou solução? Segurança Aliment. Nutr. 2018, 25, 66–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, M.H.S.; Silva Júnior, A.D.; De Pieri, J.R.S.; Toroco, B.D.R.; Oliveira, G.J.A.; Leal, J.L.P.; Olivoto, T.; Silva, E.H.C.; Zeist, A.R. Multi-Trait Selection for Mean Performance and Stability in Purple-Fleshed Sweet Potato. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2024, 174, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Andrade, E.K.V.; de Andrade Júnior, V.C.; de Laia, M.L.; Fernandes, J.S.C.; Oliveira, A.J.M.; Azevedo, A.M. Genetic Dissimilarity among Sweet Potato Genotypes Using Morphological and Molecular Descriptors. Acta Scientiarum. Agron. 2017, 39, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Frutas y Verduras—Esenciales en tu Dieta; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020; ISBN 978-92-5-133713-4. [Google Scholar]

- Pazos, J.; Zema, P.; Corbino, G.B.; Gabilondo, J.; Borioni, R.; Malec, L.S. Growing Location and Root Maturity Impact on the Phenolic Compounds, Antioxidant Activity and Nutritional Profile of Different Sweet Potato Genotypes. Food Chem. Mol. Sci. 2022, 5, 100125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katayama, K.; Kobayashi, A.; Sakai, T.; Kuranouchi, T.; Kai, Y. Recent Progress in Sweetpotato Breeding and Cultivars for Diverse Applications in Japan. Breed. Sci. 2017, 67, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roullier, C.; Rossel, G.; Tay, D.; McKey, D.; Lebot, V. Combining Chloroplast and Nuclear Microsatellites to Investigate Origin and Dispersal of New World Sweet Potato Landraces. Mol. Ecol. 2011, 20, 3963–3977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, J.A.B.; Gelsleichter, A.; Galina, J.; Silva, A.; Ribeiro, A.J.; Silva Júnior, A.D.; Guesser, S.; Zeist, A.R. Selection of Superior Sweet Potato Genotypes in the Autumn-Winter of Great Florianopolis. Hortic. Bras. 2025, 43, e286344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrud, A.C.; Zeist, A.R.; Silva Júnior, A.D.; Leal, M.H.S.; de Pieri, J.R.S.; Rodrigues Júnior, N.; Oliveira, G.J.A.; Garcia Neto, J.; Rech, C.; Marian, F. Adaptability and Stability of Sweet Potato Genotypes in Western São Paulo. Hortic. Bras. 2024, 42, e284621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngailo, S.; Shimelis, H.; Sibiya, J.; Mtunda, K.; Mashilo, J. Genotype-by-Environment Interaction of Newly-Developed Sweet Potato Genotypes for Storage Root Yield, Yield-Related Traits and Resistance to Sweet Potato Virus Disease. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva Junior, A.D.; Gomes, C.N.; Albuquerque, D.P.; Da Silva Oliveira, F.A.; Gomes, J.L.; De Melo, L.D.R.S.; Vargas, P.F.; Olivoto, T.; Zeist, A.R. Estimation of Genetic Parameters and Use of Selection Indices in the Identification of Superior Sweet Potato Genotypes. Euphytica 2025, 221, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbajal-Friedrich, A.A.J.; Burgess, A.J. The Role of the Ideotype in Future Agricultural Production. Front. Plant Physiol. 2024, 2, 1341617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Griffin, J.; Xu, J.; Ouyang, P.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, W. Identification and Quantification of Anthocyanins in Purple-Fleshed Sweet Potato Leaves. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.-S.; Stoner, G.D. Anthocyanins and Their Role in Cancer Prevention. Cancer Lett. 2008, 269, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Su, X.; Lim, S.; Griffin, J.; Carey, E.; Katz, B.; Tomich, J.; Smith, J.S.; Wang, W. Characterisation and Stability of Anthocyanins in Purple-Fleshed Sweet Potato P40. Food Chem. 2015, 186, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Naumovski, N.; Ranadheera, C.S.; D’Cunha, N.M. Nutrition-Related Health Outcomes of Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas) Consumption: A Systematic Review. Food Biosci. 2022, 50, 102208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, D.; Bedin, A.C.; Lacerda, L.G.; Nogueira, A.; Demiate, I.M. Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas L.): A Versatile Raw Material for the Food Industry. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2021, 64, e21200568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvares, C.A.; Stape, J.L.; Sentelhas, P.C.; de Moraes Gonçalves, J.L.; Sparovek, G. Köppen’s Climate Classification Map for Brazil. Meteorol. Z. 2013, 22, 711–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EMBRAPA. Sistema Brasileiro de Classificação de Solos; Embrapa: Brasília, Brazil, 2018; ISBN 978-85-7035-800-4. [Google Scholar]

- Zeist, A.R.; Carbonera, M.Z.; Rech, C.; Oliveira, G.J.A.; Toroco, B.R.; Silva Júnior, A.D.; Garcia Neto, J.; Leal, M.H.S. Soaking Time in Sulfuric Acid to Overcome Sweet Potato Seeds Dormancy. Hortic. Bras. 2024, 42, e2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, C.F.D.S.; Echer, F.R.; Batista, G.D.; Fernandes, A.M. Sweet Potato Yield and Quality as a Function of Phosphorus Fertilization in Different Soils. Rev. Bras. Eng. Agríc. Ambient. 2023, 27, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, A.M.; Ribeiro, N.P. Mineral nutrition and fertilization of sweet potato. Científica 2020, 48, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giusti, M.M.; Wrolstad, R.E. Characterization and Measurement of Anthocyanins by UV-Visible Spectroscopy. Curr. Protoc. Food Anal. Chem. 2001, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, A.; Azevedo, G.Z.; Santos, B.R.D.; Liz, M.S.M.D.; Schneider, F.S.D.S.; Rodrigues, E.R.D.O.; Moura, S.; Maraschin, M. A Guide for Quality Control of Honey: Application of UV–Vis Scanning Spectrophotometry and NIR Spectroscopy for Determination of Chemical Profiles of Floral Honey Produced in Southern Brazil. Food Humanit. 2023, 1, 1423–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivoto, T.; Diel, M.I.; Schmidt, D.; Lúcio, A.D. MGIDI: A Powerful Tool to Analyze Plant Multivariate Data. Plant Methods 2022, 18, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team R: O Projeto R Para Computação Estatística. Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Paredes, P.; López-Urrea, R.; Martínez-Romero, Á.; Petry, M.; Cameira, M.D.R.; Montoya, F.; Salman, M.; Pereira, L.S. Estimating the Lengths of Crop Growth Stages to Define the Crop Coefficient Curves Using Growing Degree Days (GDD): Application of the Revised FAO56 Guidelines. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 319, 109758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Nóbrega, D.; Peixoto, J.R.; Vilela, M.S.; da Silva Nóbrega, A.K.; Santos, E.C.; Costa, A.P.; Carmona, R. Yield and Soil Insect Resistance in Sweet Potato Clones. Biosci. J. 2019, 35, 1773–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, H.; Mei, G.; Liao, Y.; Rao, S.; Li, S.; Chen, A.; Liu, H.; Zeng, L.; et al. Natural Allelic Variation Confers High Resistance to Sweet Potato Weevils in Sweet Potato. Nat. Plants 2022, 8, 1233–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosero, A.; Pastrana, I.; Martínez, R.; Perez, J.-L.; Espitia, L.; Araujo, H.; Belalcazar, J.; Granda, L.; Jaramillo, A.; Gallego-Castillo, S. Nutritional Value and Consumer Perception of Biofortified Sweet Potato Varieties. Ann. Agric. Sci. 2022, 67, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahajeng, W.; Restuono, J.; Indriani, F.C.; Purwono, P. Evaluation of Promising Sweet Potato Clones for Higher Root Yield and Dry Matter Content. Planta Trop. 2021, 9, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhubu, F.N.; Laurie, S.M.; Rauwane, M.E.; Figlan, S. Trends and Gaps in Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas L.) Improvement in Sub-Saharan Africa: Drought Tolerance Breeding Strategies. Food Energy Secur. 2024, 13, e545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebem, E.C.; Afuape, S.O.; Chukwu, S.C.; Ubi, B.E. Genotype × Environment Interaction and Stability Analysis for Root Yield in Sweet Potato [Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam]. Front. Agron. 2021, 3, 665564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, É.M.D.; Guedes, M.L.; Crispim Filho, A.J.; Ciappina, A.L.; Reis, E.F.D.; Resende, M.P.M. Genetic Parameters and Selection for Multiple Traits in Recurrent Selection Populations of Maize. Rev. Ceres 2023, 70, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Wang, Y.; Si, C.; Kumar, S.; Nie, L.; Khan, M.N. Effects of Shading Intensities on the Yield and Contents of Anthocyanin and Soluble Sugar in Tubers of Purple Sweet Potato. Crop Sci. 2023, 63, 3013–3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouattara, F.; Agre, P.A.; Adejumobi, I.I.; Akoroda, M.O.; Sorho, F.; Ayolié, K.; Bhattacharjee, R. Multi-Trait Selection Index for Simultaneous Selection of Water Yam (Dioscorea alata L.) Genotypes. Agronomy 2024, 14, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, P.; Chakma, K.; Bhuiyan, M.S.U.; Thapa, R.; Pan, R.; Akhter, D. A Novel Multi Trait Genotype Ideotype Distance Index (MGIDI) for Genotype Selection in Plant Breeding: Application, Prospects, and Limitations. Crop Des. 2024, 3, 100074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Traits | Factor | Objective | Xo | Xs | SD | SD% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DM | FA1 | Increase | 2.74 | 3.65 | 0.918 | 33.5 |

| NTR | FA1 | Increase | 9.00 | 13.2 | 4.17 | 46.4 |

| RTY | FA1 | Increase | 963 | 1835 | 872 | 90.6 |

| NCR | FA1 | Increase | 2.77 | 6.29 | 3.52 | 127.0 |

| CRY | FA1 | Increase | 633 | 1461 | 829 | 131.0 |

| A | FA2 | Increase | 2.91 | 4.11 | 1.20 | 41.4 |

| CRY/RTY | FA2 | Increase | 52.6 | 80.2 | 27.7 | 52.6 |

| RI | FA3 | Increase | 3.32 | 3.76 | 0.445 | 13.4 |

| PC | FA3 | Increase | 3.35 | 4.71 | 1.36 | 40.6 |

| SP | FA3 | Increase | 1.90 | 3.10 | 1.96 | 11.8 |

| Trait | Factor | Objective | Xo | Xs | SD | SD% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RTY | FA1 | Increase | 2.25 | 2.55 | 2.95 | 13.1 |

| CRY | FA1 | Increase | 2.26 | 2.59 | 3.27 | 14.5 |

| SP | FA1 | Increase | 2.30 | 2.60 | 2.96 | 12.8 |

| D | FA1 | Increase | 4.96 | 5.26 | 3.08 | 6.21 |

| DRS | FA1 | Increase | 3.68 | 3.69 | 1.45 | 0.39 |

| A | FA2 | Increase | 3.83 | 3.86 | 2.89 | 0.75 |

| NCR | FA2 | Increase | 2.48 | 2.52 | 3.49 | 1.40 |

| NTR | FA2 | Increase | 8.35 | 8.74 | 3.85 | 4.61 |

| RI | FA2 | Decrease | 5.63 | 5.53 | −1.00 | −1.78 |

| PC | FA3 | Increase | 1.99 | 2.06 | 7.51 | 3.78 |

| SS | FA3 | Increase | 6.43 | 6.67 | 2.39 | 3.72 |

| NP | FA4 | Decrease | 1.53 | 1.67 | −1.00 | −1.78 |

| DM | FA5 | Increase | 1.01 | 9.04 | 1.44 | 9.41 |

| Antho | FA5 | Increase | 1.99 | 2.05 | 6.10 | 3.06 |

| Genotype | RANK | RTY (t/ha−1) | CRY (t/ha−1) | SP | D (mm) | DRS | A | NCR | NTR | RI | PC | SS (°Brix) | NP | DM | Antho (mg.g−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U1-46 | 1 | 55,000 | 53,333 | 3.0 | 77.1 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 13.0 | 15.0 | 4.0 | 9 | 5.2 | 0.1 | 227.8 | 0.397 |

| U1-145 | 2 | 38,166 | 36,833 | 4.0 | 66.0 | 5.0 | 4.0 | 6.5 | 8.0 | 5.0 | 9 | 9.4 | 0.0 | 216.0 | 0.657 |

| U2-08 | 3 | 32,916 | 31,583 | 5.0 | 69.2 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 8.5 | 12.5 | 5.0 | 9 | 10.0 | 0.5 | 162.9 | 0.425 |

| FA-08 | 4 | 18,416 | 17,250 | 4.0 | 51.8 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 11.5 | 15.0 | 4.0 | 9 | 10.0 | 0.1 | 288.6 | 0.746 |

| U2-100 | 5 | 41,250 | 35,916 | 5.0 | 51.6 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 22.5 | 34.5 | 4.5 | 9 | 8.7 | 0.0 | 203.4 | 0.174 |

| F06-32 | 6 | 49,333 | 44,958 | 5.0 | 49.4 | 4.5 | 4.0 | 22.0 | 31.5 | 5.0 | 9 | 9.5 | 0.0 | 252.8 | 0.855 |

| B-77 | 7 | 39,166 | 37,916 | 4.0 | 54.4 | 4.5 | 3.0 | 16.5 | 20.0 | 5.0 | 9 | 7.7 | 0.1 | 233.3 | 0.636 |

| U2-D | 8 | 24,083 | 21,500 | 4.0 | 47.2 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 7.5 | 13.0 | 4.0 | 9 | 3.0 | 0.0 | 185.9 | 0.548 |

| U2-47 | 9 | 24,958 | 23,958 | 4.5 | 55.4 | 3.5 | 4.0 | 9.0 | 11.5 | 4.0 | 9 | 4.2 | 0.1 | 190.7 | 0.667 |

| FA-143 | 10 | 21,083 | 19,916 | 4.0 | 63.9 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 7.0 | 9.5 | 4.0 | 9 | 6.0 | 0.6 | 230.1 | 0.560 |

| U1-123 | 11 | 50,583 | 42,083 | 5.0 | 71.3 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 16.0 | 28.0 | 5.0 | 9 | 8.4 | 0.3 | 200.0 | 0.541 |

| U1-113 | 12 | 18,250 | 15,750 | 5.0 | 50.4 | 4.5 | 4.0 | 7.5 | 13.5 | 5.0 | 9 | 6.3 | 0.5 | 199.8 | 0.455 |

| U2-49 | 13 | 12,083 | 11,583 | 2.0 | 24.5 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 5.0 | 6.5 | 1.0 | 9 | 4.5 | 0.1 | 204.3 | 0.347 |

| F06-25 | 14 | 13,916 | 11,833 | 3.0 | 38.8 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 9.5 | 15.5 | 4.0 | 9 | 5.7 | 0.0 | 182.3 | 0.361 |

| F06-199 | 15 | 26,583 | 23,666 | 3.0 | 50.8 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 18.0 | 23.5 | 4.0 | 9 | 8.0 | 0.3 | 198.6 | 0.730 |

| FA-120 | 16 | 14,250 | 12,333 | 3.0 | 50.9 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 7.0 | 12.0 | 4.0 | 9 | 11.0 | 0.8 | 206.0 | 0.804 |

| U1-55 | 17 | 17,333 | 16,750 | 4.0 | 41.4 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 4.5 | 5.5 | 5.0 | 9 | 6.9 | 0.1 | 198.0 | 0.558 |

| LP-75 | 18 | 19,416 | 17,833 | 4.0 | 56.1 | 4.0 | 4.5 | 9.5 | 12.5 | 4.5 | 9 | 8.0 | 0.0 | 196.5 | 0.570 |

| U2-74 | 19 | 24,958 | 23,958 | 4.5 | 55.4 | 3.5 | 4.0 | 9.0 | 11.5 | 4.0 | 9 | 4.2 | 0.1 | 190.7 | 0.533 |

| F06-57 | 20 | 11,750 | 8250 | 4.0 | 50.1 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 6.5 | 16.0 | 2.5 | 9 | 4.1 | 0.1 | 194.7 | 0.490 |

| U1-47 | 21 | 21,750 | 19,916 | 3.0 | 69.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 8.5 | 12.0 | 5.0 | 9 | 5.0 | 0.0 | 176.6 | 0.403 |

| CV% | - | 24.6 | 26.1 | 5.71 | 14.8 | 13.5 | 1.4 | 25.8 | 24.0 | 4.67 | 0.0 | 2.5 | 8.6 | 5.3 | 0.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Betancur González, J.A.; Junior Ribeiro, A.; Beise, D.; Guerra, E.P.; Galina, J.; Olivoto, T.; Zeist, A.R. Multicharacteristic Selection of Purple-Flesh Sweetpotato Genotypes with High Productivity and Anthocyanin Content. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1486. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121486

Betancur González JA, Junior Ribeiro A, Beise D, Guerra EP, Galina J, Olivoto T, Zeist AR. Multicharacteristic Selection of Purple-Flesh Sweetpotato Genotypes with High Productivity and Anthocyanin Content. Horticulturae. 2025; 11(12):1486. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121486

Chicago/Turabian StyleBetancur González, Jorge Andrés, Andre Junior Ribeiro, Dalvan Beise, Edson Perez Guerra, Juliano Galina, Tiago Olivoto, and André Ricardo Zeist. 2025. "Multicharacteristic Selection of Purple-Flesh Sweetpotato Genotypes with High Productivity and Anthocyanin Content" Horticulturae 11, no. 12: 1486. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121486

APA StyleBetancur González, J. A., Junior Ribeiro, A., Beise, D., Guerra, E. P., Galina, J., Olivoto, T., & Zeist, A. R. (2025). Multicharacteristic Selection of Purple-Flesh Sweetpotato Genotypes with High Productivity and Anthocyanin Content. Horticulturae, 11(12), 1486. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121486