Mapping of Cadmium Tolerance-Related QTLs at the Seedling Stage in Diploid Potato Using a High-Density Genetic Map

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

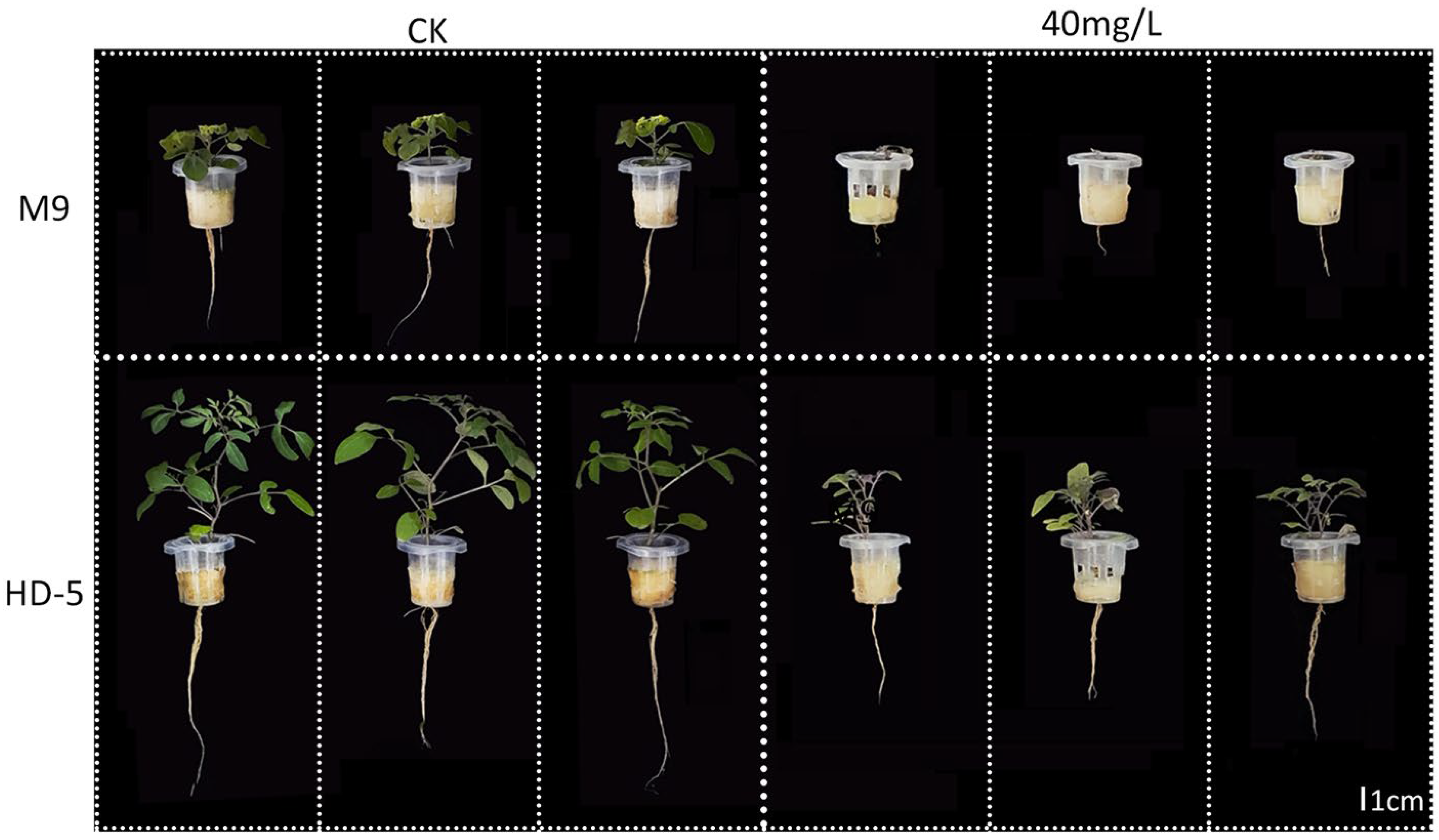

2.1. Plant Materials and Cadmium Treatment Conditions

2.2. Phenotypic Identification of Potato Seedlings

2.3. QTL Mapping Analysis

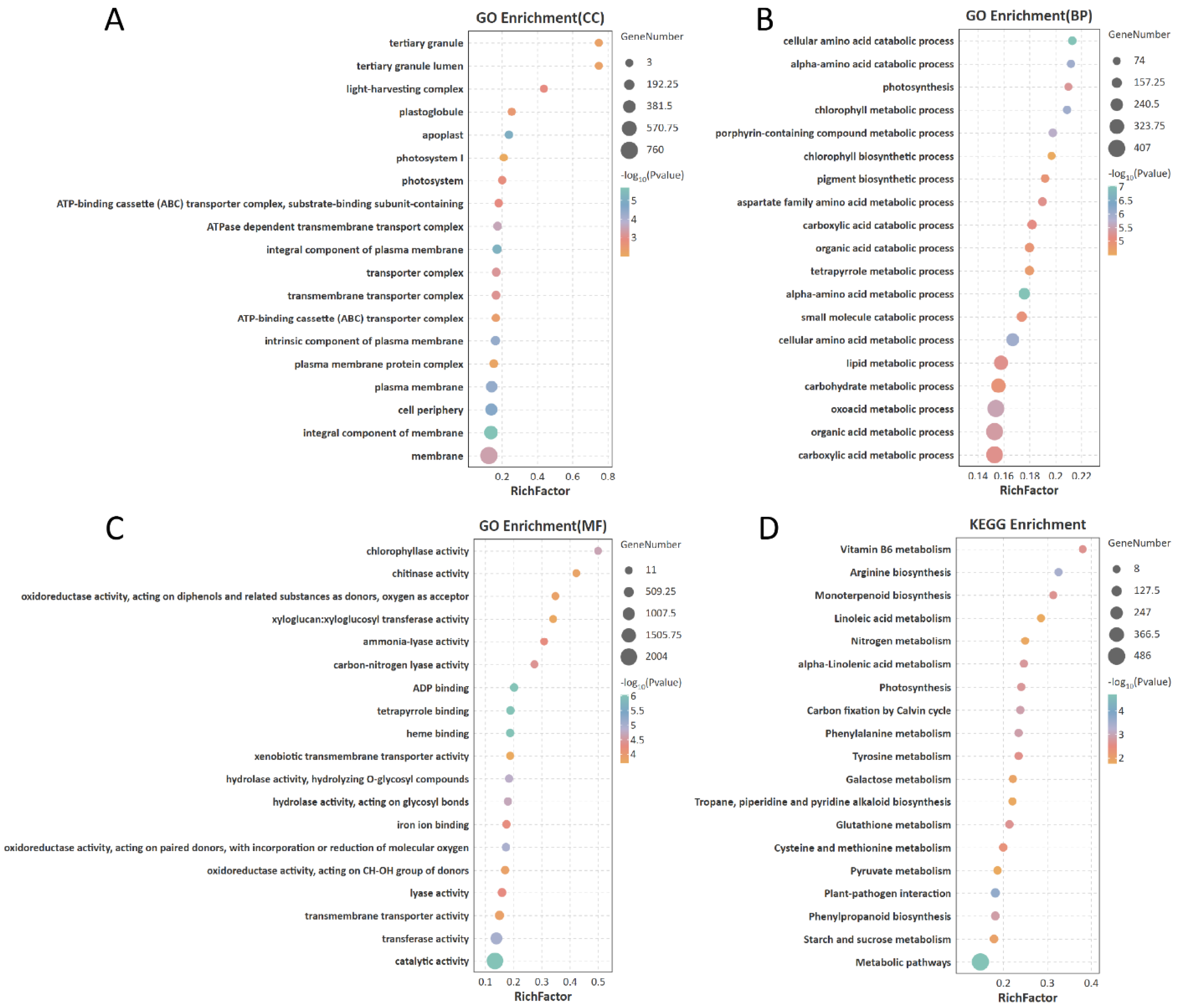

2.4. Transcriptome Sequencing and Gene Enrichment Analysis

2.5. Screening of Candidate Genes for Cadmium Tolerance in Potato

3. Results

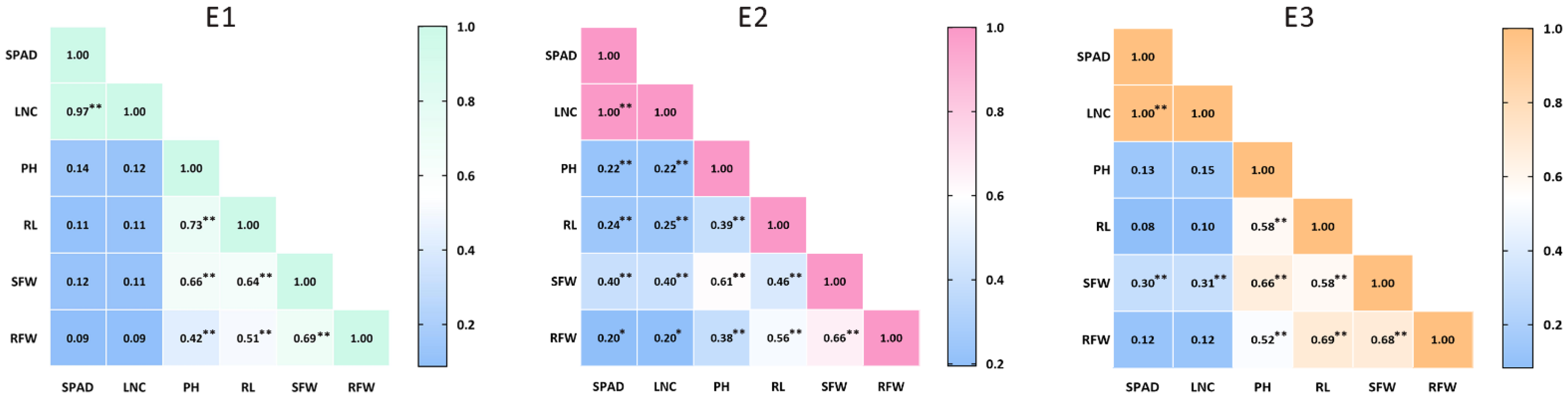

3.1. Phenotypic Analysis of Cadmium Tolerance in Parental Lines and F2 Population

3.2. QTL Mapping in the F2 Population

3.3. Identification of Stable QTLs

3.4. Effect Analysis of Five Stable QTLs

3.5. Transcriptome and Differential Gene Analysis

3.6. Screening of Candidate Genes for Cadmium Tolerance in Potato Seedlings

4. Discussion

4.1. Appropriate Genetic Population and High-Density Genetic Map Enhance QTL Mapping Efficiency

4.2. Integration of QTL Mapping and Transcriptome Analysis Facilitates Candidate Gene Mining

4.3. Cd Tolerance Candidate Genes Within Stable QTL Intervals

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Ye, Y.; Dong, W.; Luo, Y.; Fan, T.; Xiong, X.; Sun, L.; Hu, X. Cultivar diversity and organ differences of cadmium accumulation in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) allow the potential for Cd-safe staple food production on contaminated soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 711, 134534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zhou, S.; Jia, Z.; Liu, K.; Wang, G. Temporal and spatial distributions and sources of heavy metals in atmospheric deposition in western Taihu Lake, China. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 284, 117465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemens, S.; Aarts, M.G.; Thomine, S.; Verbruggen, N. Plant science: The key to preventing slow cadmium poisoning. Trends Plant Sci. 2013, 18, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angon, P.B.; Islam, S.; Kc, S.; Das, A.; Anjum, N.; Poudel, A.; Suchi, S.A. Sources, effects and present perspectives of heavy metals contamination: Soil, plants and human food chain. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, R.; Feng, X.; Zou, W.; Wang, R.; Yang, D.; Wei, W.; Li, S.; Chen, H. Converting loess into zeolite for heavy metal polluted soil remediation based on “soil for soil-remediation” strategy–ScienceDirect. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 412, 125199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizwan, M.; Ali, S.; Adrees, M.; Ibrahim, M.; Tsang, D.C.; Zia-ur-Rehman, M.; Zahir, Z.A.; Rinklebe, J.; Tack, F.M.; Ok, Y.S. A critical review on effects, tolerance mechanisms and management of cadmium in vegetables. Chemosphere 2017, 182, 90–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Zhou, W.; Dai, H.; Cao, F.; Zhang, G.; Wu, F. Selenium reduces cadmium uptake and mitigates cadmium toxicity in rice. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012, 235–236, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seth, C.S.; Chaturvedi, P.K.; Misra, V. The role of phytochelatins and antioxidants in tolerance to Cd accumulation in Brassica juncea L. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2008, 71, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertin, G.; Averbeck, D. Cadmium: Cellular effects, modifications of biomolecules, modulation of DNA repair and genotoxic consequences (a review). Biochimie 2006, 88, 1549–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarup, L.; Akesson, A. Current status of cadmium as an environmental healthproblem. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2009, 238, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhou, Y.W.; Chen, S.; Gao, X.J. Actualities, damage and management of soil cadmium pollution in China. Anhui Agric. Sci. Bull. 2015, 21, 104–107. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Abbas, T.; Rizwan, M.; Ali, S.; Adrees, M.; Zia-Ur-Rehman, M.; Qayyum, M.F.; Ok, Y.S.; Murtaza, G. Effect of biochar on alleviation of cadmium toxicity in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) grown on Cd-contaminated saline soil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 25, 25668–25680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; He, R.; Mu, X.; Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, H.; Xing, W.; Liu, D. Cadmium toxicity in plants: From transport to tolerance mechanisms. Plant Signal. Behav. 2025, 20, 2544316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najeeb, U.; Jilani, G.; Ali, S.; Sarwar, M.; Xu, L.; Zhou, W. Insights into cadmium induced physiological and ultra-structural disorders in Juncus effusus L. and its remediation through exogenous citric acid. J. Hazard. Mater. 2014, 186, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Zou, D.Y.; Xia, J.; Cui, H.Q.; Fu, S.M.; Li, B.; Zhu, Y.X.; Du, S.T. Effects of Typical Herbicides on Growth and Cadmium Accumulation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2025, 72, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, W.; Bano, R.; Bashir, S.; Aslam, Z. Cadmium toxicity and soil biological index under potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) cultivation. Soil Res. 2016, 54, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Xin, J.; Dai, H.; Liu, A.; Zhou, W.; Yi, Y.; Liao, K. Root morphological responses of three hot pepper cultivars to Cd exposure and their correlations with Cd accumulation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2015, 22, 1151–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinakar, N.; Nagajyothi, P.C.; Suresh, S.; Damodharam, T.; Suresh, C. Cadmium induced changes on proline, antioxidant enzymes, nitrate and nitrite reductases in Arachis hypogaea L. J. Environ. Biol. 2009, 30, 289–294. [Google Scholar]

- Guilherme, M.d.F.S.; Oliveira, H.M.; da Silva, E. Cadmium toxicity on seed germination and seedling growth of wheat Triticum aestivum. Acta Sci. Biol. Sci. 2015, 37, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, P.; Kumari, N.; Sharma, V. Structural and functional alterations in photosynthetic apparatus of plants under cadmium stress. Bot. Stud. 2013, 54, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hédiji, H.; Djebali, W.; Cabasson, C.; Maucourt, M.; Baldet, P.; Bertrand, A.; Zoghlami, L.B.; Deborde, C.; Moing, A.; Brouquisse, R.; et al. Effects of long-term cadmium exposure on growth and metabolomic profile of tomato plants RID B-6902-2008. Ecotox. Environ. Safe. 2010, 73, 1965–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, M.C.; Monteiro, C.; Moutinho-Pereira, J.; Correia, C.; Gonçalves, B.; Santos, C. Cadmium toxicity affects photosynthesis and plant growth at different levels. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2012, 35, 1281–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittler, R.; Vanderauwera, S.; Suzuki, N.; Miller, G.; Tognetti, V.B.; Vandepoele, K.; Gollery, M.; Shulaev, V.; Van Breusegem, F. ROS signaling: The new wave? Trends Plant Sci. 2011, 16, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, B. Reactive Species and Antioxidants. Redox Biology Is a Fundamental Theme of Aerobic Life. Plant Physiol. 2006, 141, 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grill, E.; Löffler, S.; Winnacker, E.L.; Zenk, M.H. Phytochelatins, the heavy-metal-binding peptides of plants, are synthesized from glutathione by a specific γ-glutamylcysteine dipeptidyl transpeptidase (phytochelatin synthase). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1989, 86, 6838–6842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirata, K.; Tsuji, N.; Miyamoto, K. Biosynthetic regulation of phytochelatins, heavy metal-binding peptides. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2005, 100, 593–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehra, R.; Kodati, V.; Abdullah, R. Chain Length-Dependent Pb(II)-Coordination in Phytochelatins. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995, 215, 730–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.S.; Zhang, Z. Mechanisms of cadmium phytoremediation and detoxification in plants. Crop J. 2021, 9, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Fan, T.; Zhu, X.; Wu, X.; Ouyang, J.; Jiang, L.; Cao, S. WRKY12 represses GSH1 expression to negatively regulate cadmium tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol. Biol. 2019, 99, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Cai, W.; Ji, T.T.; Ye, L.; Lu, Y.T.; Yuan, T.T. WRKY13 enhances cadmium tolerance by promoting D-CYSTEINE DESULFHYDRASE and hydrogen sulfide production. Plant Physiol. 2020, 183, 01504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhao, H.; Wu, L.; Liu, A.; Zhao, F.; Xu, W. Heavy metal ATPase 3 (HMA3) confers cadmium hypertolerance on the cadmium/zinc hyperaccumulator Sedum plumbizincicola. New Phytol. 2017, 215, 687–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.Z.; Zheng, Y.X.; Liu, H.T.; Liu, J.; Kang, G.Z. WRKY74 regulates cadmium tolerance through glutathione-dependent pathway in wheat. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 68191–68201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishimaru, K.; Hirotsu, N.; Madoka, Y.; Murakami, N.; Hara, N.; Onodera, H.; Kashiwagi, T.; Ujiie, K.; Shimizu, B.I.; Onishi, A.; et al. Loss of function of the IAA-glucose hydrolase gene TGW6 enhances rice grain weight and increases yield. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 707–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mengist, M.F.; Alves, S.; Griffin, D.; Creedon, J.; McLaughlin, M.J.; Jones, P.W.; Milbourne, D. Genetic mapping of quantitative trait loci for tuber-cadmium and zinc concentration in potato reveals associations with maturity and both overlapping and independent components of genetic control. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2018, 131, 929–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.M.; Mao, Y.; Xie, C.; Smith, H.; Luo, L.; Xu, S. Mapping Quantitative Trait Loci Using Naturally Occurring Genetic Variance Among Commercial Inbred Lines of Maize (Zea mays L.). Genetics 2005, 169, 2267–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Dong, J.; Zhao, X.; Zhao, Z.; Li, C.; Li, J.; Song, B. QTL analysis of tuber shape in a diploid potato population. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1046287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Lieshout, N.; van der Burgt, A.; de Vries, M.E.; ter Maat, M.; Eickholt, D.; Esselink, D.; van Kaauwen, M.P.W.; Kodde, L.P.; Visser, R.G.F.; Lindhout, P.; et al. Solyntus, the New Highly Contiguous Reference Genome for Potato (Solanum tuberosum). G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2020, 10, 3489–3495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindhout, P.; Meijer, D.; Schotte, T.; Hutten, R.C.; Visser, R.G.; van Eck, H.J. Towards F 1 Hybrid Seed Potato Breeding. Potato Res. 2011, 54, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Yao, C.; Miao, J.; Li, N.; Ji, F.; Hu, D.; Wang, S.; Zhou, Z.; Dai, K.; Chen, A.; et al. Construction of a High-Density Genetic Map and QTL Mapping Analysis for Yield, Tuber Shape, and Eye Number in Diploid Potato. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noctor, G.; Foyer, C.H. Ascorbate and glutathione: Keeping active oxygen under control. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 1998, 49, 249–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hell, R.; Bergmann, L. λ-Glutamylcysteine synthetase in higher plants: Catalytic properties and subcellular localization. Planta 1990, 180, 603–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hell, R.; Bergmann, L. Glutathione synthetase in tobacco suspension cultures: Catalytic properties and localization. Physiol. Plant 1988, 72, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Tang, D.; Huang, W.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Hamilton, J.P.; Visser, R.G.F.; Bachem, C.W.B.; Buell, C.R.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Haplotype-resolved genome analyses of a heterozygous diploid potato. Nat. Genet. 2020, 52, 1018–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; He, Y.Q.; Ye, T.T.; Huang, X.; Wu, H.; Ma, T.X.; Pritchard, H.W.; Wang, X.F.; Xue, H. Glutathionylation of a glycolytic enzyme promotes cell death and vigor loss during aging of elm seeds. Plant Physiol. 2024, 195, 2596–2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, D.; Viquez-Zamora, M.; van Eck, H.J.; Hutten, R.C.B.; Su, Y.; Rothengatter, R.; Visser, R.G.F.; Lindhout, W.H.; van Heusden, A.W. QTL mapping in diploid potato by using selfed progenies of the cross S. tuberosum × S. chacoense. Euphytica 2018, 214, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, H.; Li, N.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, S.; Wang, Q.; Wang, H. Fine-Mapping Quantitative Trait Loci for Body Weight and Abdominal Fat Traits: Effects of Marker Density and Sample Size. Poult. Sci. 2008, 87, 1314–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Sun, K.; Li, D.; Luo, L.; Liu, Y.; Huang, M.; Yang, G.; Liu, H.; Wang, H.; Chen, Z.; et al. Identification of stable QTLs and candidate genes involved in anaerobic germination tolerance in rice via high-density genetic mapping and RNA-Seq. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.J.; Han, X.M.; Ren, L.L.; Yang, H.L.; Zeng, Q.Y. Functional divergence of the glutathione S-transferase supergene family in Physcomitrella patens reveals complex patterns of large gene family evolution in land plants. Plant Physiol. 2013, 161, 773–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammou, R.A.; Ben El Caid, M.; Harrouni, C.; Daoud, S. Germination enhancement, antioxidant enzyme activity, and metabolite changes in late Argania spinosa kernels under salinity. J. Arid. Environ. 2023, 219, 105095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Badri, A.M.; Batool, M.; AAMohamed, I.; Wang, Z.; Khatab, A.; Sherif, A.; Ahmad, H.; Khan, M.N.; Hassan, H.M.; Elrewainy, I.M.; et al. Antioxidative and Metabolic Contribution to Salinity Stress Responses in Two Rapeseed Cultivars during the Early Seedling Stage. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Traits a | Env b | Parents c | F2 Population | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HD-5 | M9 | Mean ± SD d | Range | Skewness | Kurtosis | CV (%) e | ||

| SPAD | 1 | 44.167 ± 5.024 | 28.747 ± 1.992 ** | 41.78 ± 8.03 | 48.13 | −1.43 | 3.93 | 19.23% |

| 2 | 46.433 ± 9.264 | 28.300 ± 0.608 ** | 33.07 ± 10.11 | 49.73 | −0.13 | −0.22 | 30.56% | |

| 3 | 44.070 ± 2.729 | 27.433 ± 3.677 | 27.90 ± 10.61 | 54.50 | 0.30 | −0.02 | 38.05% | |

| LNC | 1 | 13.800 ± 1.480 | 8.433 ± 1.097 ** | 12.99 ± 2.41 | 14.43 | −1.36 | 3.76 | 18.53% |

| 2 | 14.500 ± 2.778 | 8.880 ± 0.485 | 10.48 ± 3.05 | 14.88 | −0.14 | −0.29 | 29.12% | |

| 3 | 13.337 ± 1.125 | 8.877 ± 1.813 * | 8.93 ± 3.20 | 16.30 | 0.28 | −0.10 | 35.90% | |

| PH (cm) | 1 | 10.533 ± 1.343 | 2.667 ± 1.172 ** | 7.47 ± 2.37 | 12.45 | 0.19 | 0.12 | 31.69% |

| 2 | 12.800 ± 0.529 | 2.133 ± 0.987 ** | 9.42 ± 2.26 | 11.80 | 0.22 | 0.07 | 23.98% | |

| 3 | 7.333 ± 0.907 | 4.200 ± 0.200 ** | 7.93 ± 2.30 | 11.93 | 0.16 | −0.37 | 28.98% | |

| RL (cm) | 1 | 6.000 ± 0.100 | 3.500 ± 0.656 ** | 6.11 ± 3.11 | 13.60 | 0.19 | −0.59 | 50.95% |

| 2 | 11.400 ± 0.700 | 2.367 ± 1.026 ** | 5.30 ± 2.37 | 12.70 | 0.75 | 0.61 | 44.71% | |

| 3 | 5.627 ± 1.476 | 3.333 ± 2.013 | 6.64 ± 3.13 | 15.90 | 0.44 | 0.21 | 47.11% | |

| SFW (g) | 1 | 0.743 ± 0.263 | 0.027 ± 0.011 ** | 0.32 ± 0.26 | 1.13 | 1.42 | 1.89 | 78.99% |

| 2 | 0.771 ± 0.013 | 0.020 ± 0.002 ** | 0.24 ± 0.14 | 0.83 | 1.54 | 3.88 | 57.64% | |

| 3 | 0.238 ± 0.075 | 0.022 ± 0.004 * | 0.25 ± 0.17 | 0.68 | 0.78 | −0.25 | 67.08% | |

| RFW (g) | 1 | 0.047 ± 0.023 | 0.047 ± 0.025 | 0.04 ± 0.03 | 0.20 | 1.99 | 6.07 | 84.47% |

| 2 | 0.027 ± 0.003 | 0.004 ± 0.001 ** | 0.02 ± 0.03 | 0.14 | 1.98 | 4.35 | 109.07% | |

| 3 | 0.018 ± 0.005 | 0.004 ± 0.001 * | 0.04 ± 0.04 | 0.23 | 2.10 | 5.24 | 111.74% | |

| Loci | QTLs a | Chr. b | Physical Interval (bp) | PVE(%) c | Add d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1oci 1 | qRL−1−1 | 1 | 29,012,218–57,317,677 | 13.3385 | −0.7984 |

| 1oci 2 | qRL−1−2 | 1 | 5,351,673–29,012,218 | 12.9135 | −2.1055 |

| 1oci 3 | qRL−1−3 | 1 | 37,611,070–74,578,147 | 8.1859 | −0.9840 |

| 1oci 4 | qPH−2−1 | 2 | 41,692,984–41,775,216 | 7.0634 | −0.9950 |

| 1oci 5 | qLNC−2−1 | 2 | 44,946,567–45,032,374 | 9.4553 | −1.1362 |

| 1oci 6 | qPH−3−1 | 3 | 40,338,972–40,605,160 | 10.1101 | 1.2234 |

| 1oci 7 | qPH−3−2 | 3 | 47,919,207–48,169,736 | 14.6916 | 1.4137 |

| 1oci 8 | qLNC−3−1 | 3 | 49,754,021–49,807,802 | 9.8225 | −1.2750 |

| 1oci 9 | qSFW−4−1 | 4 | 66,983,369–67,065,497 | 10.2155 | −0.0772 |

| 1oci 10 | qRL−4−1 | 4 | 68,948,711–68,973,381 | 7.2827 | −1.1359 |

| 1oci 11 | qRL−5−1 | 5 | 525,953–569,416 | 6.9233 | −1.1279 |

| 1oci 12 | qLNC−5−1 | 5 | 8,408,228–9,112,966 | 10.0734 | 1.8651 |

| qSPAD−5−1 | 5 | 8,408,228–9,112,966 | 9.3672 | 6.0306 | |

| 1oci 13 | qSPAD−5−2 | 5 | 48,644,133–48,762,977 | 15.6618 | −0.7231 |

| 1oci 14 | qRL−6−1 | 6 | 49,522,733–50,501,032 | 21.9897 | 0.0792 |

| 1oci 15 | qSPAD−7−1 | 7 | 346,576–17,733,723 | 11.9017 | 5.3474 |

| qLNC−7−1 | 7 | 346,576–17,733,723 | 11.6027 | 1.6182 | |

| qSFW−7−1 | 7 | 346,576–17,733,723 | 9.4890 | 0.1134 | |

| 1oci 16 | qSPAD−7−2 | 7 | 35,052,784–38,088,263 | 8.6965 | 4.5112 |

| qLNC−7−2 | 7 | 35,052,784–38,088,263 | 8.3207 | 1.3958 | |

| 1oci 17 | qRFW−8−1 | 8 | 2,748,041–2,758,469 | 10.0285 | −0.0021 |

| 1oci 18 | qPH−8−1 | 8 | 7,997,098–31,535,030 | 8.7767 | 0.0605 |

| 1oci 19 | qSFW−8−1 | 8 | 50,926,157–53,711,582 | 10.8234 | −0.0279 |

| qPH−8−2 | 8 | 50,926,157–53,711,582 | 9.6140 | −1.2853 | |

| 1oci 20 | qRL−8−1 | 8 | 58,986,198–59,037,631 | 1.3025 | −1.1749 |

| 1oci 21 | qPH−9−1 | 9 | 306,152–1,285,423 | 11.9977 | −0.1802 |

| qSFW−9−1 | 9 | 306,152–1,285,423 | 13.9843 | −0.0323 | |

| qRFW−9−1 | 9 | 306,152–1,285,423 | 11.1250 | −0.0009 | |

| 1oci 22 | qRL−9−1 | 9 | 1,466,439–2,079,646 | 6.7259 | −0.1402 |

| qSFW−9−2 | 9 | 1,466,439–2,079,646 | 2.2921 | −0.0700 | |

| qSPAD−9−1 | 9 | 1,466,439–2,079,646 | 5.3037 | −5.1453 | |

| qLNC−9−1 | 9 | 1,466,439–2,079,646 | 6.0150 | −1.7924 | |

| 1oci 23 | qSPAD−9−2 | 9 | 1,919,479–23,211,947 | 5.3037 | −5.1453 |

| qLNC−9−2 | 9 | 1,919,479–23,211,947 | 6.0150 | −1.7924 | |

| 1oci 24 | qSFW−9−3 | 9 | 3,044,644–3,087,171 | 12.9603 | −0.1434 |

| 1oci 25 | qRL−9−2 | 9 | 4,652,558–4,707,033 | 4.8812 | −0.9193 |

| 1oci 26 | qRL−9−3 | 9 | 58,794,345–58,978,509 | 4.7732 | −0.3706 |

| 1oci 27 | qRL−9−4 | 9 | 60,012,674–60,053,731 | 7.6266 | −1.1940 |

| 1oci 28 | qRL−9−5 | 9 | 64,160,910–67,058,125 | 4.4546 | −0.0799 |

| 1oci 29 | qPH−10−1 | 10 | 59,631,719–60,825,257 | 7.7293 | −0.2199 |

| qSPAD−10−1 | 10 | 59,631,719–60,825,257 | 11.6191 | −3.8553 | |

| qLNC−10−1 | 10 | 59,631,719–60,825,257 | 3.5926 | −0.8455 | |

| qSPAD−10−2 | 10 | 59,631,719–60,825,257 | 6.4580 | −5.8361 | |

| qLNC−10−2 | 10 | 59,631,719–60,825,257 | 6.6984 | −1.8112 | |

| 1oci 30 | qSFW−11−1 | 11 | 37,433,151–37,547,309 | 11.6941 | −0.1081 |

| 1oci 31 | qSFW−12−1 | 12 | 7,107,959–56,641,152 | 9.4688 | 0.2960 |

| qRFW−12−1 | 12 | 7,107,959–56,641,152 | 7.8364 | 0.1114 | |

| qRFW−12−2 | 12 | 7,107,959–56,641,152 | 6.5686 | 0.0734 | |

| qPH−12−1 | 12 | 7,107,959–56,641,152 | 10.1266 | 0.1935 | |

| 1oci 32 | qRL−12−1 | 12 | 23,254,518–52,646,079 | 1.8663 | 0.1982 |

| 1oci 33 | qSPAD−12−1 | 12 | 34,326,932–36,818,274 | 6.2909 | −8.3609 |

| qLNC−12−1 | 12 | 34,326,932–36,818,274 | 9.1109 | −2.5908 | |

| qRL−12−2 | 12 | 34,326,932–36,818,274 | 11.4310 | −1.9586 | |

| 1oci 34 | qSFW−12−2 | 12 | 13,637,732–14,326,899 | 6.2020 | −0.0410 |

| 1oci 35 | qSPAD−12−2 | 12 | 20,523,649–30,259,744 | 4.7350 | −5.0345 |

| qLNC−12−2 | 12 | 20,523,649–30,259,744 | 4.7797 | −1.5651 |

| Stable | Stable QTLs | Traits | Number of Lines | Donor of Positive Allele | Phenotypic Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loci | Paternal Genotype (M9) | Heterozygous Genotype | Maternal Genotype (HD-5) | Paternal Genotype (M9) | Heterozygous Genotype | Maternal Genotype (HD-5) | |||

| Loci21 | qPH−9−1 | PH (cm) | 37 | 25 | 55 | HD-5 | 6.530 b | 7.035 b | 8.369 a |

| qSFW−9−1 | SFW (g) | 37 | 22 | 53 | 0.216 b | 0.315 ab | 0.411 a | ||

| qRFW−9−1 | RFW (g) | 26 | 25 | 53 | 0.018 b | 0.032 ab | 0.048 a | ||

| Loci22 | qRL−9−1 | RL (cm) | 38 | 27 | 51 | HD-5 | 4.915 b | 6.054 ab | 7.117 a |

| qSFW−9−2 | SFW (g) | 38 | 24 | 49 | 0.205 b | 0.320 a | 0.389 a | ||

| qSPAD−9−1 | SPAD | 39 | 29 | 46 | 29.991 b | 33.543 ab | 35.127 a | ||

| qLNC−9−1 | LNC | 40 | 29 | 46 | 9.670 b | 10.660 ab | 11.100 a | ||

| Loci29 | qPH−10−1 | PH (cm) | 41 | 22 | 48 | HD-5 | 8.563 b | 9.580 ab | 9.811 a |

| qSPAD−10−1 | SPAD | 27 | 20 | 47 | 41.133 ab | 38.330 b | 42.497 a | ||

| qLNC−10−1 | LNC | 39 | 22 | 45 | 9.500 b | 10.300 ab | 11.147 a | ||

| qSPAD−10−2 | SPAD | 24 | 21 | 36 | 24.910 a | 26.022 a | 29.150 a | ||

| qLNC−10−2 | LNC | 24 | 21 | 37 | 8.010 a | 8.275 a | 9.253 a | ||

| Loci31 | qSFW−12−1 | SFW (g) | 28 | 21 | 37 | M9 | 0.351 a | 0.237 a | 0.270 a |

| qRFW−12−1 | RFW(g) | 28 | 21 | 36 | 0.044 a | 0.042 a | 0.029 a | ||

| qRFW−12−2 | RFW (g) | 22 | 26 | 36 | 0.044 a | 0.035 a | 0.029 a | ||

| qPH−12−1 | PH (cm) | 32 | 27 | 48 | 10.217 a | 8.933 a | 8.379 a | ||

| Loci33 | qSPAD−12−1 | SPAD | 34 | 11 | 48 | HD-5 | 16.779 b | 32.689 a | 33.377 a |

| qLNC−12−1 | LNC | 34 | 11 | 48 | 5.588 b | 10.426 a | 10.512 a | ||

| qRL−12−2 | RL (cm) | 34 | 11 | 48 | 4.608 b | 7.902 a | 6.011 ab | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Su, L.; Li, X.; Ning, L.; Shu, P.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Z.; Peng, X.; Liu, H.; Yuan, Y.; Yuan, D.; et al. Mapping of Cadmium Tolerance-Related QTLs at the Seedling Stage in Diploid Potato Using a High-Density Genetic Map. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1478. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121478

Su L, Li X, Ning L, Shu P, Zhang Q, Liu Z, Peng X, Liu H, Yuan Y, Yuan D, et al. Mapping of Cadmium Tolerance-Related QTLs at the Seedling Stage in Diploid Potato Using a High-Density Genetic Map. Horticulturae. 2025; 11(12):1478. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121478

Chicago/Turabian StyleSu, Ling, Xinqi Li, Lixing Ning, Peng Shu, Qingyi Zhang, Zugen Liu, Xiong Peng, Huili Liu, Yuan Yuan, Dingbo Yuan, and et al. 2025. "Mapping of Cadmium Tolerance-Related QTLs at the Seedling Stage in Diploid Potato Using a High-Density Genetic Map" Horticulturae 11, no. 12: 1478. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121478

APA StyleSu, L., Li, X., Ning, L., Shu, P., Zhang, Q., Liu, Z., Peng, X., Liu, H., Yuan, Y., Yuan, D., Liu, G., You, G., Chen, J., Liu, X., Tao, Y., Feng, Y., & Yang, J. (2025). Mapping of Cadmium Tolerance-Related QTLs at the Seedling Stage in Diploid Potato Using a High-Density Genetic Map. Horticulturae, 11(12), 1478. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121478