Physiological Stress, Yield, and N and P Use Efficiency in an Intensive Tomato–Tilapia Aquaponic System

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

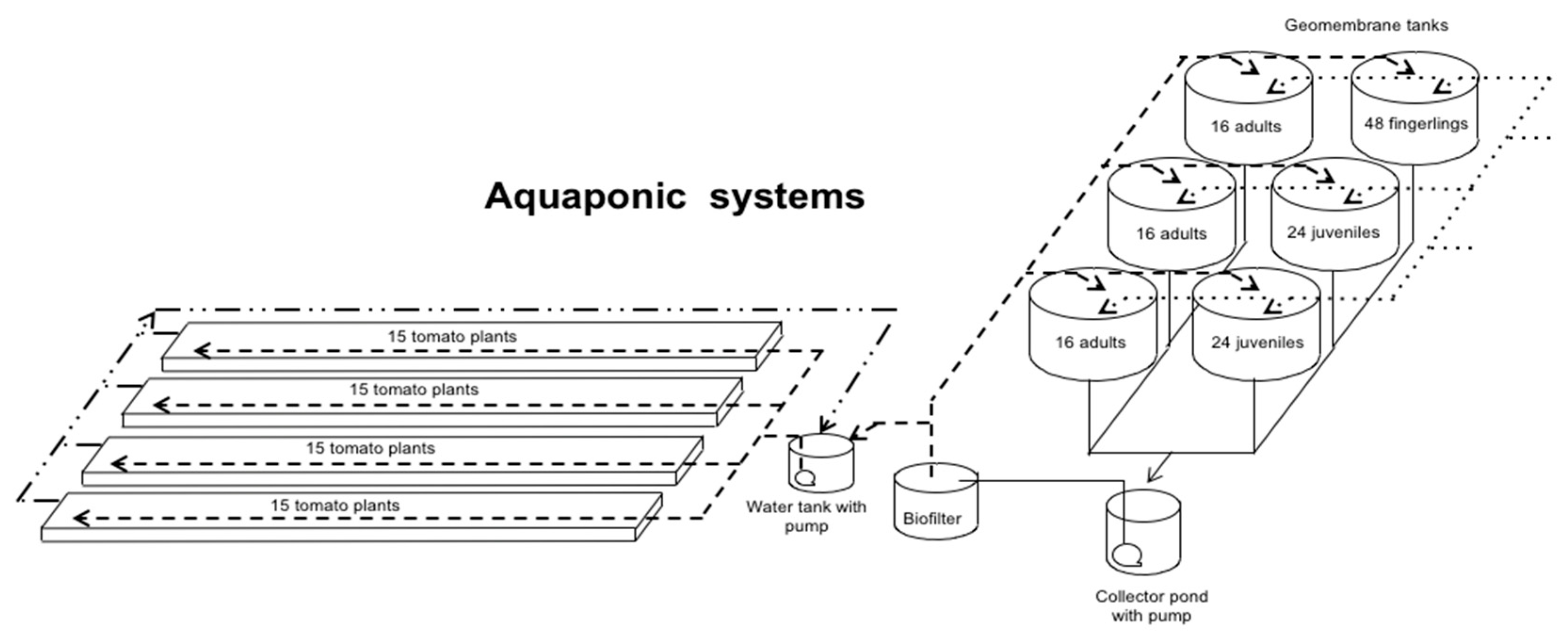

2.1. System Description

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Biological Material

2.4. Management of Organisms

2.5. Water Quality

2.6. Stress Indicators

2.7. Productive Performance

2.8. Efficiency in the Use of Nitrogen and Phosphorus

2.9. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Water Quality

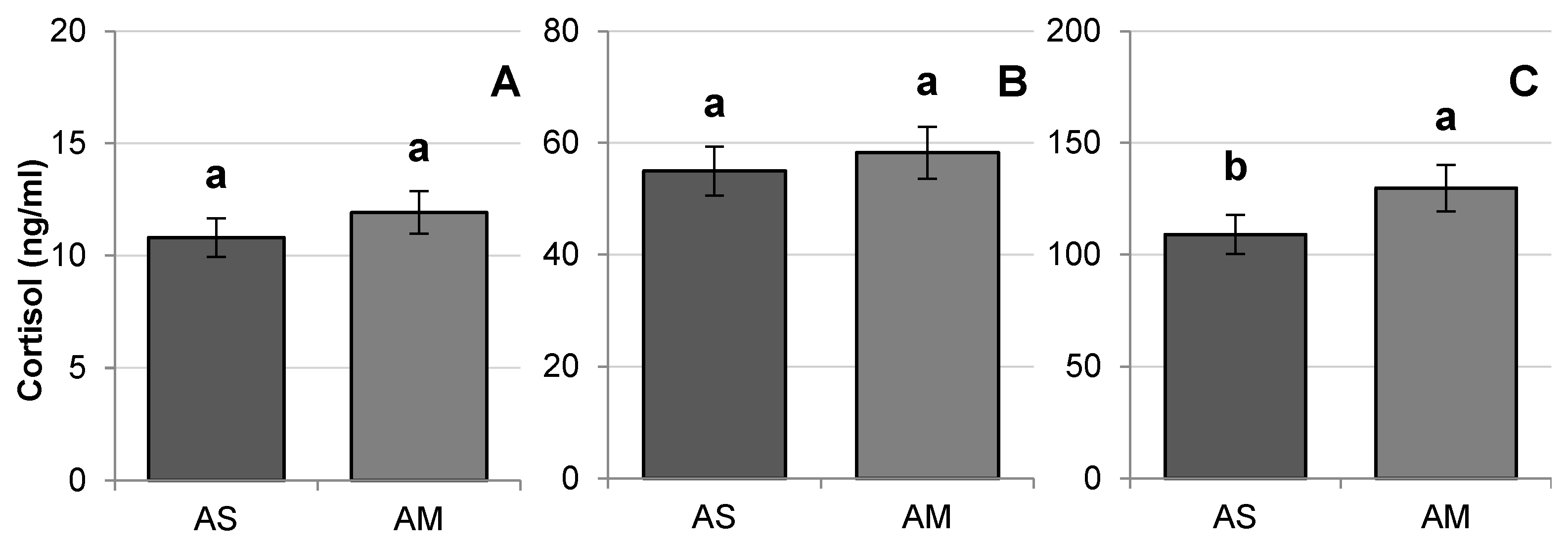

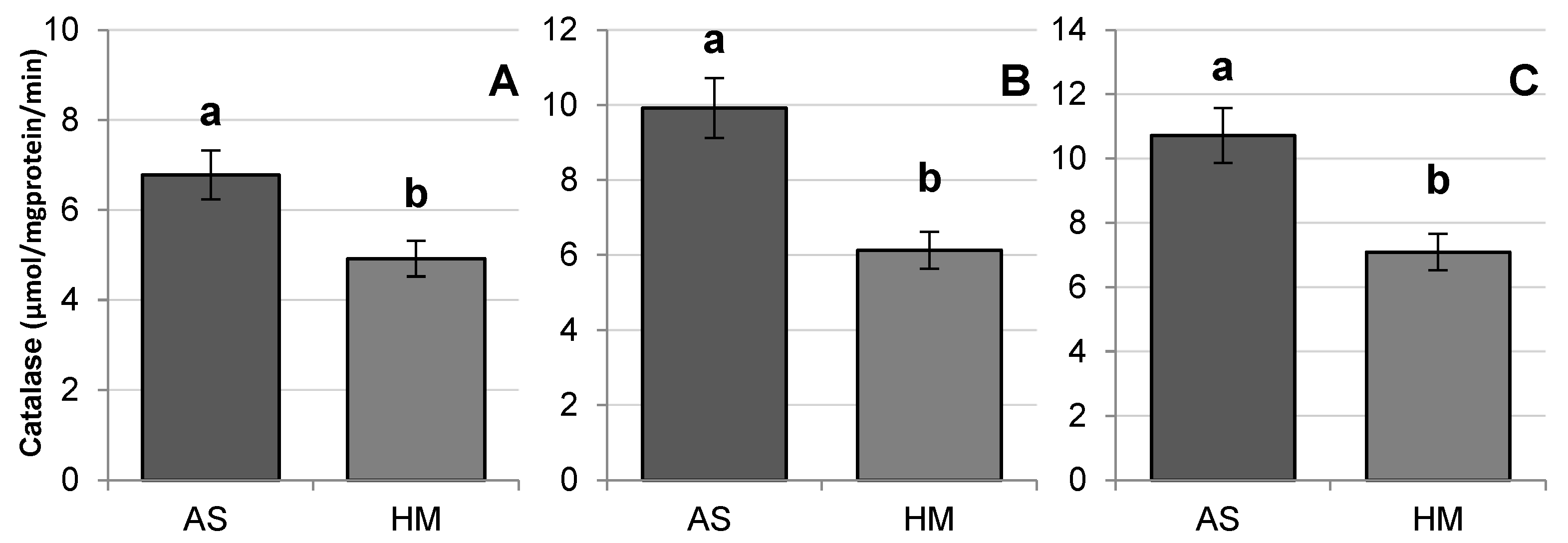

3.2. Stress Indicators

3.3. Productive Performance

4. Discussion

4.1. Water Quality

4.2. Stress Indicators

4.3. Productive Performance

4.4. Nitrogen Use Efficiency (NUE) and Phosphorus Use Efficiency (PUE)

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hawkesworth, S.; Dangour, A.D.; Johnston, D.; Lock, K.; Poole, N.; Rushton, J.; Uauy, R.; Waage, J. Feeding the world healthily: The challenge of measuring the effects of agriculture on health. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 2010, 365, 3083–3097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, A.; Malone, S.; Morris, Z.; Weissburg, M.; Bras, B. Combined Fish and Lettuce Cultivation: An Aquaponics Life Cycle Assessment. Procedia CIRP 2018, 69, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, D.C.; Fry, J.P.; Li, X.; Hill, E.S.; Genello, L.; Semmens, K.; Thompson, R.E. Commercial aquaponics production and profitability: Findings from an international survey. Aquaculture 2015, 435, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forchino, A.A.; Lourguioui, H.; Brigolina, D.; Pastresa, R. Aquaponics and sustainability: The comparison of two different aquaponic techniques using the Life Cycle Assessment (LCA). Aquac. Eng. 2017, 77, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, M.; Islam, M.S.; Das, P.; Das, P.R.; Akter, M. Comparative study on proximate composition and amino acids of probiotics treated and nontreated cage reared monosex tilapia Oreochromis niloticus in Dekar haor, Sunamganj district, Bangladesh. Int. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2018, 62, 431–435. [Google Scholar]

- Beckles, D.M. Factors affecting the postharvest soluble solids and sugar content of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2012, 63, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmautz, Z.; Loeu, F.; Liebisch, F.; Graber, A.; Mathis, A.; Griessler Bulc, T.; Junge, R. Tomato productivity and quality in aquaponics: Comparison of three hydroponic methods. Water 2016, 8, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhl, J.; Dannehl, D.; Kloas, W.; Baganz, D.; Jobs, S.; Scheibe, G.; Schmidt, U. Advanced aquaponics: Evaluation of intensive tomato production in aquaponics vs. conventional hydroponics. Agric. Water Manag. 2016, 178, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kralik, B.; Nieschwitz, N.; Neves, K.; Zeedyk, N.; Wildschutte, H.; Kershaw, J. The effect of aquaponics on tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) sensory, quality, and safety outcomes. J. Food Sci. 2023, 88, 2261–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashley, P.J. Fish welfare: Current issues in aquaculture. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2007, 104, 199–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dara, M.; Carbonara, P.; La Corte, C.; Parrinello, D.; Cammarata, M.; Parisi, M.G. Fish welfare in aquaculture: Physiological and immunological activities for diets, social and spatial stress on Mediterranean aqua cultured species. Fishes 2023, 8, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotedar, S.; Evans, L. Health management during handling and live transport of crustaceans: A review. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2011, 106, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Porchas, M.; Martínez-Córdova, L.R.; Ramos-Enriquez, R. Cortisol and glucose: Reliable indicators of fish stress? Pan-Am. J. Aquat. Sci. 2009, 4, 158–178. [Google Scholar]

- Zárate-Martínez, W.; González-Morales, S.; Ramírez-Godina, F.; Robledo-Olivo, A.; Juárez-Maldonado, A. Effect of phenolic acids on the antioxidant system of tomato plants (Solanum lycopersicum Mill.). Agron. Mesoam. 2021, 32, 854–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Merino, F.C.; Trejo-Téllez, L.I. Biostimulant activity of phosphite in horticulture. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 196, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goddek, S.; Delaide, B.; Mankasingh, U.; Ragnarsdottir, K.V.; Jijakli, H.; Thorarinsdottir, R. Challenges of sustainable and commercial aquaponics. Sustainability 2015, 7, 4199–4224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongkiew, S.; Hu, Z.; Chandran, K.; Lee, J.W.; Khanal, S.K. Nitrogen transformations in aquaponic systems: A review. Aquac. Eng. 2017, 76, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Félix-Cuencas, L.; García-Trejo, J.F.; López-Tejeida, S.; León-Ramírez, J.J.D.; Soto-Zarazúa, G.M. Effect of three productive stages of tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) under hyper-intensive recirculation aquaculture system on the growth of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum). Lat. Am. J. Aquat. Res. 2021, 49, 689–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercado-Luna, A. Manual de Producción de Jitomate (Lycopersicon esculentum) en Variedades de Crecimiento Indeterminado Bajo Invernadero; Universidad Autónoma de Querétaro: Santiago de Querétaro, Mexico, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Camello, A. Manual Para la Preparacion y Venta de Frutas y Hortalizas, 1st ed.; Servicios Agrícolas de la FAO: Rome, Italy, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Aparicio-Simón, B.; Piñón, M.; Racotta, R.; Racotta, I.S. Neuroendocrine and metabolic responses of Pacific whiteleg shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei exposed to acute handling stress. Aquaculture 2010, 298, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Aoki, A.; Arimoto, T.; Nakano, T.; Ohnuki, H.; Murata, M.; Ren, H.; Endo, H. Fish stress become visible: A new attempt to use biosensor for real-time monitoring fish stress. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2015, 67, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankhurst, N.W. The endocrinology of stress in fish: An environmental perspective. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2011, 170, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Tawwab, M.; Mousa, M.A.; Sharaf, S.M.; Ahmad, M.H. Effect of crowding stress on some physiological functions of Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus (L.) fed different dietary protein levels. Int. J. Zool. Res. 2005, 1, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Santiago-Rucinque, D.; Polo, G.; Borbón, J.; González Mantilla, J.F. Anesthetic use of eugenol and benzocaine in juveniles of red tilapia. Rev. Colomb. Cienc. Pecu. 2017, 30, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, L.A.K.A.; MorAes, G.; IwAMA, G.K.; Afonso, L.O.B. Physiological stress responses in the warm-water fish matrinxã (Brycon amazonicus) subjected to a sudden cold shock. Acta Amaz. 2008, 38, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraz, Y.G.; El-Hawarry, W.N.; Shourbela, R.M. Culture Performance of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) raised in a bioflocbased intensive system. Alex. J. Vet. Sci. 2018, 58, 166–172. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, T.; Li, C.; Ma, F.; Feng, F.; Shu, H. Responses of growth and antioxidant system to root-zone hypoxia stress in two Malus species. Plant Soil 2010, 327, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parola-Contreras, I.; Tovar-Perez, E.G.; Rojas-Molina, A.; Luna-Vazquez, F.J.; Torres-Pacheco, I.; Ocampo-Velazquez, R.V.; Guevara-González, R.G. Changes in affinin contents in Heliopsis longipes (chilcuague) after a controlled elicitation strategy under greenhouse conditions. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 148, 112314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejía-Teniente, L.; Durán-Flores, F.d.D.; Chapa-Oliver, A.M.; Torres-Pacheco, I.; Cruz-Hernández, A.; González-Chavira, M.M.; Ocampo-Velázquez, R.V.; Guevara-González, R.G. Oxidative and molecular responses in Capsicum annuum L. after hydrogen peroxide, salicylic acid and chitosan foliar applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 10178–10196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arab, M.; Bahramian, B.; Schindeler, A.; Valtchev, P.; Dehghani, F.; McConchie, R. Extraction of phytochemicals from tomato leaf waste using subcritical carbon dioxide. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2019, 57, 102204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidar, M.N.; Bleeker, S.; Heinsbroek, L.T.N.; Schrama, J.W. Effect of constant digestible protein intake and varying digestible energy levels on energy and protein utilization in Nile tilapia. Aquaculture 2018, 489, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Trejo, J.F.; Peña-Herrejon, G.A.; Soto-Zarazúa, G.M.; Mercado-Luna, A.; Alatorre-Jácome, O.; Rico-García, E. Effect of stocking density on growth performance and oxygen consumption of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) under greenhouse conditions. Lat. Am. J. Aquat. Res. 2016, 44, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Rosa-Rodríguez, R.; Lara-Herrera, A.; Lozano-Gutiérrez, J.; Padilla-Bernal, L.E.; Avelar-Mejía, J.J.; Castañeda-Miranda, R. Rendimiento y calidad de tomate en sistemas hidropónicos abierto y cerrado. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agrícolas 2016, 17, 3439–3452. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Zhang, B.; Luo, P.; Shi, H.; Li, L.; Gao, Y.; Lee, C.T.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, W.M. Performance of a pilot-scale aquaponics system using hydroponics and immobilized biofilm treatment for water quality control. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 208, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Rosa-Rodríguez, R.D.L.; Lara-Herrera, A.; Trejo-Téllez, L.I.; Padilla-Bernal, L.E.; Solis-Sánchez, L.O.; Ortiz-Rodríguez, J.M. Water and fertilizers use efficiency in two hydroponic systems for tomato production. Hortic. Bras. 2020, 38, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC—Association of Official Analytical Chemistry. Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International, 17th ed.; AOAC International: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2000; 2200p. [Google Scholar]

- Wortman, S.E. Crop physiological response to nutrient solution electrical conductivity and pH in an ebb- and-flow hydroponic system. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 194, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgadillo-Díaz, M.; Gullian-Klanian, M.; Sosa-Moguel, O.; Sauri-Duch, E.; Cuevas-Glory, L.F. Evaluation of physico-chemical characteristics, antioxidant compounds and antioxidant capacity in creole tomatoes (Solanum lycopersicum L. and S. pimpinellifolium L.) in an aquaponic system or organic soil. Int. J. Veg. Sci. 2019, 25, 124–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Flores, M.; Sandoval-Villa, M.; Rodríguez-Mendoza, M.D.L.N.; Trejo-Téllez, L.I. Tomato quality (Solanum lycopersicum L.) produced in aquaponics complemented with foliar fertilization of micronutrients. Agroproductividad 2020, 13, 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- Tyl, C.; Sadler, G.D. pH and Titratable Acidity. In Food Analysis; Nielsen, S.S., Ed.; Food Science Text Series; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 389–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fish, W.W.; Perkins-Veazie, P.; Collins, J.K. Aquantitative assay for lycopene that utilizes reduced volumes of organic solvents. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2002, 15, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Kim, H.J. Comparisons of nitrogen and phosphorus mass balance for tomato-, basil-, and lettuce-based aquaponic and hydroponic systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 274, 122619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Hack, M.E.; El-Saadony, M.T.; Nader, M.M.; Salem, H.M.; El-Tahan, A.M.; Soliman, S.M.; Khafaga, A.F. Effect of environmental factors on growth performance of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Int. J. Biometeorol. 2022, 66, 2183–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azaza, M.S.; Dhraïef, M.N.; Kraïem, M.M. Effects of water temperature on growth and sex ratio of juvenile Nile tilapia Oreochromis niloticus (Linnaeus) reared in geothermal waters in southern Tunisia. J. Therm. Biol. 2008, 33, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomalá, D.; Chavarría, J.; Escobar, B.E. Evaluación de la tasa de consumo de oxígeno de Colossoma macropomum en relación al peso corporal y temperatura del agua. Lat. Am. J. Aquat. Res. 2014, 42, 971–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calone, R.; Pennisi, G.; Morgenstern, R.; Sanyé-Mengual, E.; Lorleberg, W.; Dapprich, P.; Winkler, P.; Orsini, F.; Gianquinto, G. Improving water management in European catfish recirculating aquaculture systems through catfish-lettuce aquaponics. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 687, 759–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, J.S.; Takahashi, L.S.; Hoshiba, M.A.; Urbinati, E.C. Biological indicators of stress in pacu (Piaractus mesopotamicus) after capture. Braz. J. Biol. 2009, 69, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, R.E.; Volpato, G.L. Stress responses of the fish Nile tilapia subjected to electroshock and social stressors. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2006, 39, 1605–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajimura, S.; Hirano, T.; Visitacion, N.; Moriyama, S.; Aida, K.; Grau, E.G. Dual mode of cortisol action on GH/IGF-I/IGF binding proteins in the tilapia, Oreochromis mossambicus. J. Endocrinol. 2003, 178, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeitoun, M.M.; El-Azrak, K.M.; Zaki, M.A.; Allah, B.N.; Mehana, E.E. Consequences of environ- mental stressors on hematological parameters, blood glucose, cortisol and phagocytic activity of Nile tilapia fish. J. Agric. Ecol. Res. Int. 2017, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, S.F.; Lima, I.M.; Modolo, L.V. Phenolic content and antioxidant activity of parts of Passiflora edulis as a function of plant developmental stage. Acta Bot. Bras. 2019, 34, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Dong, C.; Gao, W. Evaluation of the growth, photosynthetic characteristics, antioxidant capacity, biomass yield and quality of tomato using aeroponics, hydroponics and porous tube-vermiculite systems in bio-regenerative life support systems. Life Sci. Space Res. 2019, 22, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javanmardi, J.; Akbari, N. Salicylic acid at different plant growth stages affects secondary metabolites and phisicochemical parameters of greenhouse tomato. Adv. Hortic. Sci. 2016, 30, 151–158. [Google Scholar]

- Rayhan, M.Z.; Rahman, M.A.; Hossain, M.A.; Akter, T.; Akter, T. Effect of stocking density on growth performance of monosex tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) with Indian spinach (Basella alba) in a recirculating aquaponic system. Int. J. Environ. Agric. Biotechnol. 2018, 3, 239073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.M.; Verma, A.K.; Krishna, H.; Prakash, S.; Kumar, A.; Peter, R.M. Effect of salinity on growth of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) and spinach (Spinacia oleracea) in aquaponic system using inland saline groundwater. Aquac. Res. 2021, 52, 6288–6298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migiro, K.E.; Ogello, E.O.; Munguti, J.M. The length-weight relationship and condition factor of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus L.) broodstock at Kegati Aquaculture Research Station, Kisii, Kenya. Int. J. Adv. Res. 2014, 2, 777–782. [Google Scholar]

- Yıldız, H.Y.; Bekcan, S. Role of stocking density of tilapia (Oreochromis aureus) on fish growth, water quality and tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) plant biomass in the aquaponic system. Int. J. Environ. Agric. Biotechnol. 2017, 2, 238971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monsees, H.; Klatt, L.; Kloas, W.; Wuertz, S. Chronic exposure to nitrate significantly reduces growth and affects the health status of juvenile Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus L.) in recirculating aquaculture systems. Aquac. Res. 2017, 48, 3482–3492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Flores, M.; Sandoval-Villa, M.; Rodríguez-Mendoza, N.; Trejo-Téllez, L.I.; Sánchez-Escudero, J.; Reta-Mendiola, J. Concentración de nutrientes en efluente acuapónico para producción de Solanum lycopersicum L. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agrícolas 2016, 17, 3529–3542. [Google Scholar]

- Williams Ayarna, A.; Tsukagoshi, S.; Oduro Nkansah, G.; Lu, N.; Maeda, K. Evaluation of tropical tomato for growth, yield, nutrient, and water use efficiency in recirculating hydroponic system. Agriculture 2020, 10, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perin, L.; Peil, R.M.; Trentin, R.; Streck, E.A.; Signorini, C.; Grolli, P.R. Production ecophysiology of the grafted and non-grafted tomato plants grown in substrate. Hortic. Bras. 2023, 41, e2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, F.B.; Martinez, H.E.P.; Silva, D.J.H.D.; Milagres, C.D.C.; Barbosa, J.G. Yield and quality of tomato grown in a hydroponic system, with different planting densities and number of bunches per plant. Pesqui. Agropecuária Trop. 2018, 48, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herath, S.S.; Haga, Y.; Satoh, S. Effects of long-term feeding of corn co-product-based diets on growth, fillet color, and fatty acid and amino acid composition of Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus. Aquaculture 2016, 464, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yep, B.; Zheng, Y. Aquaponic trends and challenges–A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 228, 1586–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, C.S.; Manoharan, R.; Nishanth, D.; Subramanian, R.; Neumann, E.; Jaleel, A. Recent advancements in aquaponics with special emphasis on its sustainability. J. World Aquac. Soc. 2025, 56, e13116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaduzzaman, M.; Niu, G.; Asao, T. Nutrients recycling in hydroponics: Opportunities and challenges toward sustainable crop production under controlled environment agriculture. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 845472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Productive Stage | Initial Weight (Individual) | Number of Fish | Number of Tanks | Expected Final Weight (Individual) | Expected Final Biomass |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fingerling | 5.65 ± 0.12 g | 48 | 1 | 50 g | 2.4 kg |

| Juvenile | 51.13 ± 2.73 g | 24 | 2 | 150 g | 3.6 kg |

| Adult | 150.98 ± 8.21 g | 16 | 3 | 250 g | 4.0 kg |

| Stage | Weight Range per Fish | Protein | Lipid | Daily Percentage of Feed | Feeding Times |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fingerling | 5–20 g | 45% | 16% | 8% | 8:00 am (30%) 13:00 pm (40%) 18:00 pm (30%) |

| Fingerling | 20–50 g | 45% | 16% | 5% | |

| Juvenile | 50–150 g | 35% | 3% | 4% | |

| Adult | 150–300 g | 30% | 3% | 2% |

| Stage | Irrigation Volume Per Plant | Schedules and Irrigation Ration |

|---|---|---|

| Vegetative | 1.5 L | 10:00 am (30%) 14:00 pm (40%) 16:00 pm (30%) |

| Flowering | 2.4 L | |

| Fructification | 3.6 L | |

| Maturation | 2.4 L |

| Variable | Reference Values [44] | Aquaponic System (AS) | Aquaculture Module (AM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature (°C) | 20–32 | 24.1 ± 1.1 a | 23.7 ± 1.4 a |

| Dissolved Oxygen (mg L−1) | 4–10 | 6.81 ± 0.36 a | 6.73 ± 0.38 a |

| pH | 5–9 | 7.8 ± 0.5 a | 8.1 ± 0.6 a |

| Nitrates (mg L−1) | <100 | 21.05 ± 3.84 b | 32.02 ± 3.03 a |

| Nitrites (mg L−1) | <5 | 1.13 ± 0.76 b | 2.92 ± 0.85 a |

| Non-ionized ammonia (mg L−1) | <2 | 0.81 ± 0.13 b | 1.19 ± 0.14 a |

| Variable | Reference Values [19] | Aquaponic System (AS) | Hydroponic Module (HM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 5.5–6.5 | 6.3 ± 0.3 a | 5.7 ± 0.2 b |

| Dissolved Oxygen (mg L−1) | 5–8 | 4.82 ± 0.26 a | 3.61 ± 0.29 b |

| Electrical Conductivity (mS) | 1.5–2.5 | 2.2 ± 0.3 a | 1.6 ± 0.2 b |

| Fingerling | Juvenile | Adult | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | AS | AM | AS | AM | AS | AM |

| TWG (g) | 54.66 ± 2.03 a | 51.33 ± 3.74 a | 99.79 ± 4.23 a | 95.53 ± 3.98 ab | 115.45 ±4.92 a | 114.43 ±4.78 a |

| DWG (g) | 0.91 ± 0.05 a | 0.85 ± 0.08 a | 1.66 ± 0.07 a | 1.59 ± 0.06 a | 1.92 ± 0.08 a | 1.90 ± 0.07 a |

| FCF | 1.74 ± 0.07 b | 1.98 ± 0.06 a | 1.72 ± 0.09 a | 1.87 ± 0.08 a | 1.69 ± 0.08 b | 1.83 ± 0.09 ab |

| PE | 1.43 ± 0.06 a | 1.26 ± 0.06 b | 1.64 ± 0.06 a | 1.53 ± 0.08 a | 1.85 ± 0.05 a | 1.73 ± 0.09 ab |

| SGR | 3.81 ± 0.12 a | 3.59 ± 0.09 b | 1.69 ± 0.05 a | 1.68 ± 0.02 a | 0.92 ± 0.03 a | 0.73 ± 0.04 b |

| CF | 0.82 ± 0.02 a | 0.80 ± 0.03 a | 1.16 ± 0.05 a | 1.07 ± 0.04 b | 1.19 ± 0.05 a | 1.27 ± 0.08 a |

| SR (%) | 89.6 ± 2.1 a | 82 ± 2.0 b | 94.6 ± 1.5 a | 93.2 ± 0.9 a | 97.5 ± 0.9 b | 100 ± 0.0 a |

| Fingerling | Juvenile | Adult | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | AS | HM | AS | HM | AS | HM |

| PH (cm) | 52.6 ± 4.1 a | 53.4 ± 3.9 a | 72.5 ± 3.2 b | 84.1 ± 7.2 a | 117.4 ± 6.8 b | 134.7 ± 4.2 a |

| DW (g) | 135.34 ± 5.42 b | 145.92 ± 4.73 a | 208.79 ±9.37 ab | 218.02 ± 8.13 a | 304.67 ±13.63 b | 345.86 ±16.52 a |

| RGR (g g−1 day−1) | 0.085 ± 0.003 b | 0.102 ± 0.003 a | 0.024 ± 0.001 b | 0.033 ± 0.004 a | 0.020 ± 0.001 b | 0.025 ± 0.002 a |

| PSR (%) | 94.2 ± 2.1 a | 95.2 ± 1.6 a | 89.8 ± 1.9 ab | 94.7 ± 3.2 a | 85.4 ± 2.1 b | 97.9 ± 4.1 a |

| LA (cm2) | 1285 ± 50 b | 1840 ± 65 a | 1780 ± 35 b | 2445 ± 45 a | 2345 ± 40 b | 2895 ± 35 a |

| LAI | 1.71 ± 0.06 b | 2.45 ± 0.10 a | 2.37 ± 0.05 b | 3.26 ± 0.07 a | 3.12 ± 0.06 b | 3.86 ± 0.05 a |

| SLA (cm2 g−1) | 9.49 ± 0.33 b | 12.61 ± 0.47 a | 8.51 ± 0.21 b | 11.21 ± 0.42 a | 7.69 ± 0.22 b | 8.37 ± 0.23 a |

| NAR (gcm−2day−1) | 0.0054 ± 0.0002 a | 0.0053 ± 0.0001 a | 0.0027 ± 0.0001 a | 0.0029 ± 0.0001 a | 0.0025 ± 0.0001 a | 0.0026 ± 0.0001 a |

| CGR (gcm−2day−1) | 0.027 ± 0.001 b | 0.034 ± 0.002 a | 0.058 ± 0.002 b | 0.086 ± 0.002 a | 0.072 ± 0.002 b | 1.001 ± 0.003 a |

| Treatment | Total kg of Tomato | Tomato Productivity kg m−2 | Total kg of Tilapia | Tilapia Productivity kg m−3 | Water Use Efficiency (kg Fruit and Fish m−3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AS | 32.2 | 3.22 | 32.6 | 36.2 | 5.4 |

| AM | 41.8 | 4.18 | 29.2 | 32.4 | 4.6 |

| Variable | Aquaponic System AS | Aquaculture Module AM |

|---|---|---|

| Moisture (%) | 61.98 ± 0.11 b | 64.23 ± 0.12 a |

| Protein (%) | 28.15 ± 0.81 a | 24.98 ± 0.73 b |

| Lipid (%) | 3.42 ± 0.16 a | 3.51 ± 0.14 a |

| Ash (%) | 1.71 ± 0.04 a | 1.42 ± 0.04 b |

| Nitrogen-Free Extract (%) | 2.74 ± 0.05 b | 2.86 ± 0.08 a |

| Variable | Aquaponic System AS | Hydroponic Module AM |

|---|---|---|

| pH | 4.49 ± 0.09 a | 4.12 ± 0.11 b |

| SST (°Brix) | 6.42 ± 0.21 a | 5.66 ± 0.12 b |

| TA (%) | 0.57 ± 0.04 a | 0.51 ± 0.03 b |

| TSS/TA (%) | 11.26 ± 0.13 a | 11.09 ± 0.23 a |

| Lycopene (mg g−1) | 45.18 ± 0.09 b | 63.27 ± 0.12 a |

| Variable | Aquaponic System AS | Aquaculture Module AM | Hydroponic Module HM |

|---|---|---|---|

| NUE | 23.35 ± 2.41 b | 11.44 ± 1.33 c | 49.61 ± 2.28 a |

| PUE | 20.71 ± 1.92 b | 11.45 ± 1.09 c | 24.82 ± 1.13 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

De león-Ramírez, J.J.; García-Trejo, J.F.; Sosa-Ferreyra, C.F.; Félix-Cuencas, L.; López-Tejeida, S. Physiological Stress, Yield, and N and P Use Efficiency in an Intensive Tomato–Tilapia Aquaponic System. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1474. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121474

De león-Ramírez JJ, García-Trejo JF, Sosa-Ferreyra CF, Félix-Cuencas L, López-Tejeida S. Physiological Stress, Yield, and N and P Use Efficiency in an Intensive Tomato–Tilapia Aquaponic System. Horticulturae. 2025; 11(12):1474. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121474

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe león-Ramírez, Jesús Josafat, Juan Fernando García-Trejo, Carlos Francisco Sosa-Ferreyra, Leticia Félix-Cuencas, and Samuel López-Tejeida. 2025. "Physiological Stress, Yield, and N and P Use Efficiency in an Intensive Tomato–Tilapia Aquaponic System" Horticulturae 11, no. 12: 1474. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121474

APA StyleDe león-Ramírez, J. J., García-Trejo, J. F., Sosa-Ferreyra, C. F., Félix-Cuencas, L., & López-Tejeida, S. (2025). Physiological Stress, Yield, and N and P Use Efficiency in an Intensive Tomato–Tilapia Aquaponic System. Horticulturae, 11(12), 1474. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121474