Mass Modeling of Six Loquat (Eriobotrya japonica Lindl.) Varieties for Post-Harvest Grading Based on Physical Attributes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. Regression Analysis and Model Development

3. Results

3.1. Physical Attributes

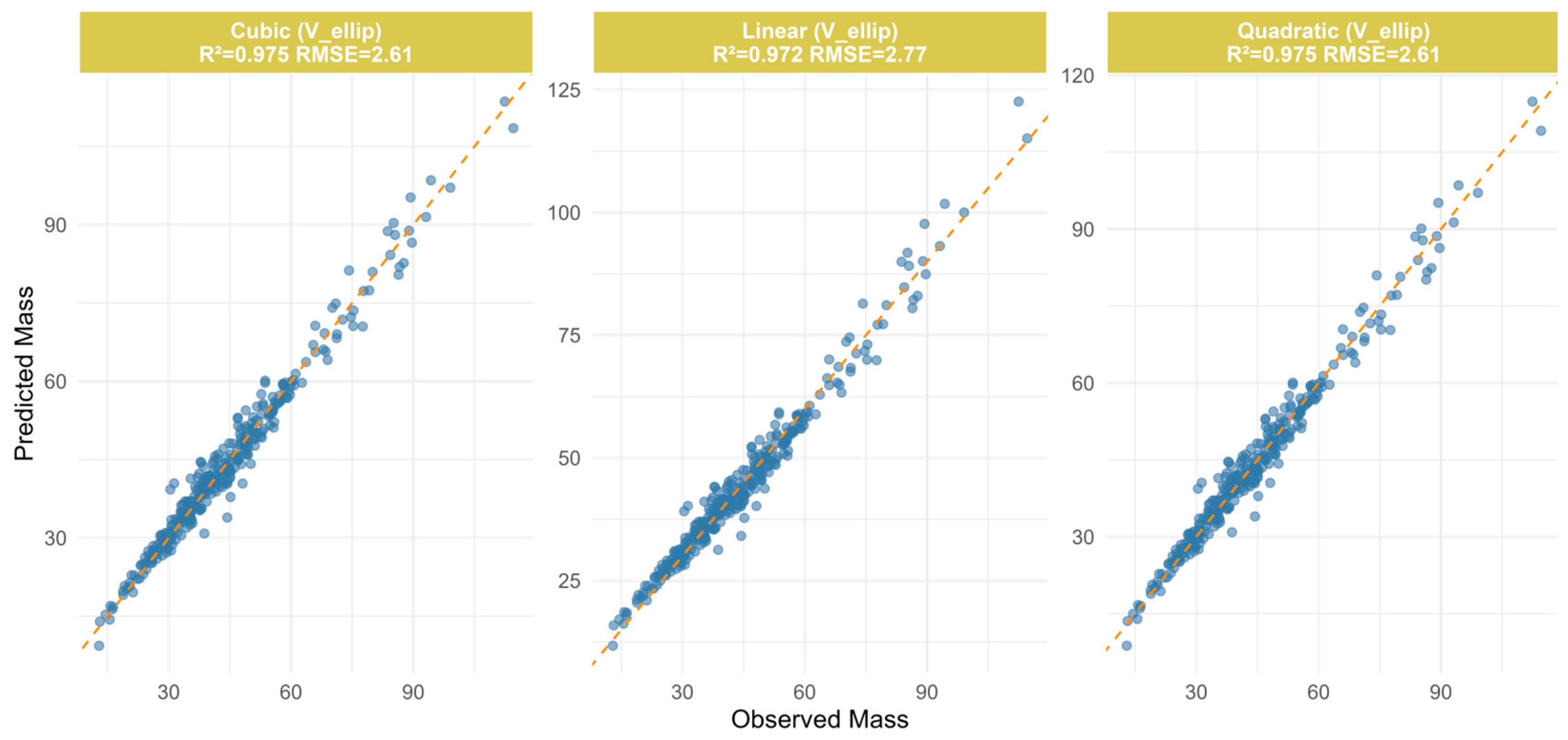

3.2. Mass Modeling

3.3. General Regression Mass Model per Predictor

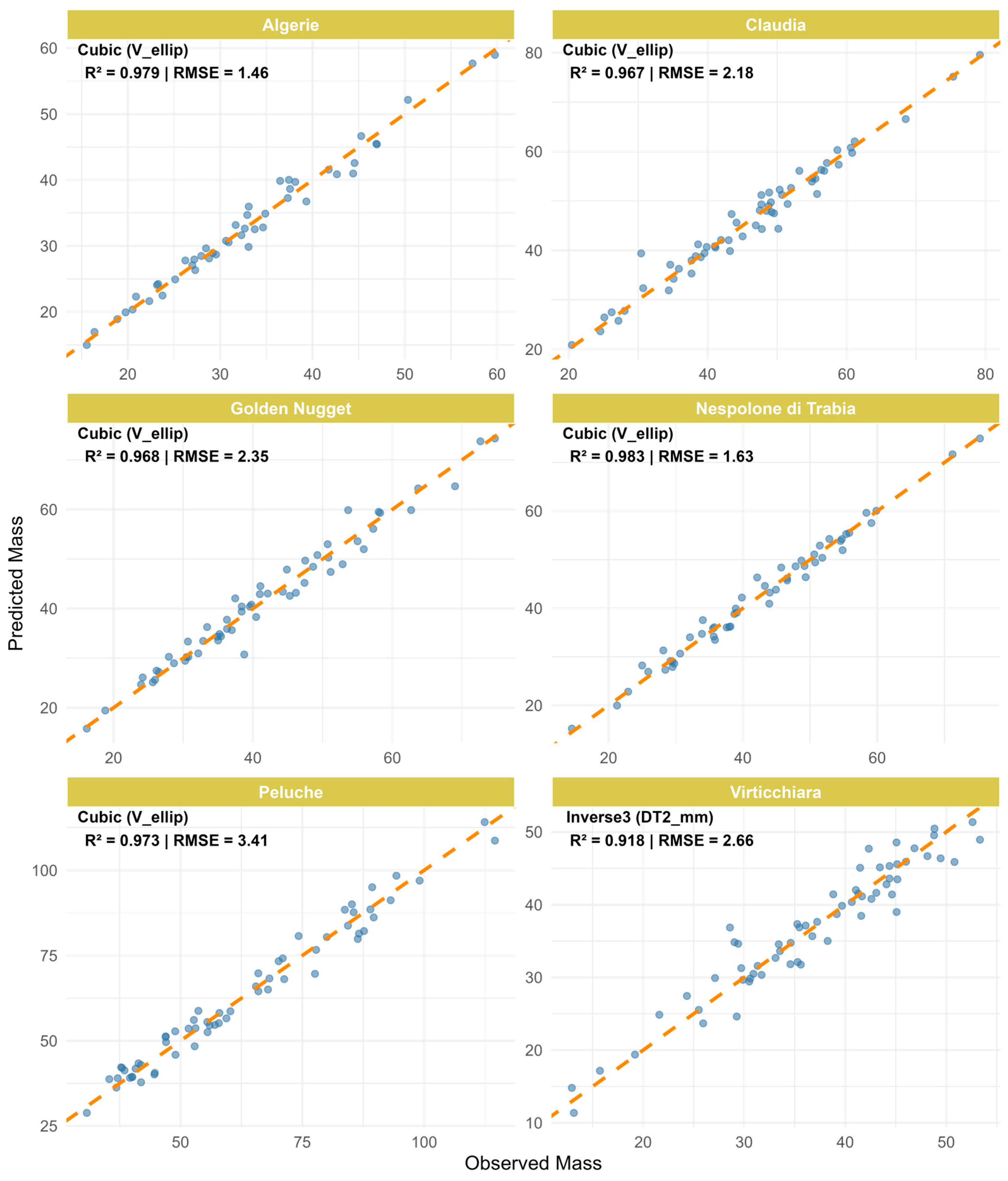

3.4. Mass Modeling per Variety

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tous, J.; Ferguson, L. Mediterranean Fruits. Prog. New Crops 1996, 416, 430. [Google Scholar]

- Caballero, P.; Fernández, M.A. Loquat, Production and Market. Options Mediterraéens Ser. A Semin. Mediterranéens 2003, 58, 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Reig, C.; Farina, V.; Volpe, G.; Mesejo, C.; Martínez-Fuentes, A.; Barone, F.; Calabrese, F.; Agustí, M. Gibberellic Acid and Flower Bud Development in Loquat (Eriobotrya japonica Lindl.). Sci. Hortic. 2011, 129, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, R.; Migliore, G.; Schifani, G.; Tinebra, I.; Farina, V. Chemical–Physical, Sensory Analyses and Consumers’ Quality Perception of Local vs. Imported Loquat Fruits: A Sustainable Development Perspective. Agronomy 2020, 10, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarrasi, V.; Farina, V.; Germanà, M.A.; San Biagio, P.L.; Mazzaglia, A. Fruit quality evaluation of four loquat cultivars grown in sicily. Acta Hortic. 2011, 887, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Calvo, J.; Badenes, M.L.; Llácer, G. Descripción de Variedades de Níspero Japonés; Generalitat Valenciana, Consellería de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación, IVIA: Valencia, Spain, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Tinebra, I.; Passafiume, R.; Scuderi, D.; Pirrone, A.; Gaglio, R.; Palazzolo, E.; Farina, V. Effects of Tray-Drying on the Physicochemical, Microbiological, Proximate, and Sensory Properties of White- and Red-Fleshed Loquat (Eriobotrya japonica Lindl.) Fruit. Agronomy 2022, 12, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara, G.; Takahashi, C.; Nagaya, M.; Uemura, K. Application of Radio Frequency Heating in Water for Extending the Shelf-Life of Fresh-Cut Japanese Loquat Fruit (Eriobotrya japonica). Food Sci. Technol. Res. 2021, 27, 847–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farina, V.; Gianguzzi, G.; Mazzaglia, A. Fruit Quality Evaluation of Affirmed and Local Loquat (Eriobotrya japonica Lindl) Cultivars Using Instrumental and Sensory Analyses. Fruits 2016, 71, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, C.; Reig, C.; Corona, O.; Todaro, A.; Mazzaglia, A.; Perrone, A.; Gianguzzi, G.; Agusti, M.; Farina, V. Pomological Traits, Sensory Profile and Nutraceutical Properties of Nine Cultivars of Loquat (Eriobotrya japonica Lindl.) Fruits Grown in Mediterranean Area. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2016, 71, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gliński, J.; Horabik, J.; Lipiec, J. Agrophysical Properties and Processes in Encyclopedia of Agrophysics; Springer Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; p. 35. [Google Scholar]

- Kılıçkan, A.; Güner, M. Physical Properties and Mechanical Behavior of Olive Fruits (Olea europaea L.) Under Compression Loading. J. Food Eng. 2008, 87, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kambhampati, V.; Mishra, S.; Pradhan, R. Physicochemical Characterization and Mass Modelling of Sohiong (Prunus nepalensis L.) Fruit. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2018, 12, 923–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmedo-Obrero, G.; Perea, C.A.; Arturo, M.; Cruz, E.; Venegas-Ordoñez, M.; López-Canteñs, G.; Serna Abascal, C. Physical characterization and mass modeling by geometrical attributes of black sapote (Diospyros nigra (J.F.Gmel.) Perr.). Agrociencia 2024, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altuntas, E.; Mahawar, M. Mass Modeling of Potato Cultivars with Different Shape Index by Physical Characteristics. J. Food Process Eng. 2022, 45, e14126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibwe, B.; Mahawar, M.K.; Jalgaonkar, K.; Meena, V.S.; Kadam, D.M. Mass Modeling of Guava (Cv. Allahabad safeda) Fruit with Selected Dimensional Attributes: Regression Analysis Approach. J. Food Process Eng. 2022, 45, e13978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahawar, M.K.; Bibwe, B.; Jalgaonkar, K.; Ghodki, B.M. Mass Modeling of Kinnow Mandarin Based on Some Physical Attributes. J. Food Process Eng. 2019, 42, e13079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birania, S.; Attkan, A.K.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, N.; Singh, V.K. Mass Modeling of Strawberry (Fragaria × Ananasa) Based on Selected Physical Attributes. J. Food Process Eng. 2022, 45, e14023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbazi, F.; Rahmati, S. Mass Modeling of Sweet Cherry (Prunus avium L.) Fruit with Some Physical Characteristics. Food Nutr. Sci. 2013, 4, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, S.S.; Pradhan, R.C.; Mishra, S. Physical Characterization and Mass Modeling of Dried Terminalia chebula Fruit. J. Food Process Eng. 2019, 42, e12992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbazi, F.; Rahmati, S. Mass Modeling of Fig (Ficus carica L.) Fruit with Some Physical Characteristics. Food Sci. Nutr. 2013, 1, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoshnam, F.; Tabatabaeefar, A.; Varnamkhasti, M.G.; Borghei, A. Mass Modeling of Pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) Fruit with Some Physical Characteristics. Sci. Hortic. 2007, 114, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani Firouz, M.; Alimardani, R.; Omid, M. Modeling the Main Physical Properties of Banana Fruit Based on Geometrical Attributes. Int. J. Multidiscip. Sci. Eng. 2011, 2, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Mossad, A.; El Helew, W.K.M.; Elsheshetawy, H.E.; Farina, V. Mass Modelling by Dimension Attributes for Mango (Mangifera indica Cv. Zebdia) Relevant to Post-Harvest and Food Plants Engineering. Agric. Eng. Int. CIGR J. 2016, 18, 219–229. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, P.; Sit, N. Physicochemical Characterization of Spanish Cherry (Mimusops elengi) Fruit at Different Growth Stages and Its Mass Modelling Using Machine Learning Algorithms. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2024, 18, 3906–3922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahi-Gharahlar, A.; Yavari, A.R.; Khanali, M. Mass and Volume Modeling of Loquat (Eriobotrya japonica Lindl.) Fruit Based on Physical Characteristics. J. Fruit. Ornam. Plant Res. 2009, 17, 175–189. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Calvo, J.; Badenes, M.; Llácer, G.; Bleiholder, H.; Hack, H.; Meier, U. Phenological Growth Stages of Loquat Tree (Eriobotrya japonica (Thunb.) Lindl.). Ann. Appl. Biol. 1999, 134, 353–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarimopas, B.; Nunak, T.; Nunak, N. Electronic Device for Measuring Volume of Selected Fruit and Vegetables. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2005, 35, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsenin, N.N. Physical Properties of Plant and Animal Materials: V. 1: Physical Characteristics and Mechanical Properties; Routledge: London, UK, 1970; ISBN 1-00-012263-8. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (Version 4.4.2); R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2022; Available online: http://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Miranda, J.C.; Gené-Mola, J.; Zude-Sasse, M.; Tsoulias, N.; Escolà, A.; Arnó, J.; Rosell-Polo, J.R.; Sanz-Cortiella, R.; Martínez-Casasnovas, J.A.; Gregorio, E. Fruit Sizing Using AI: A Review of Methods and Challenges. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2023, 206, 112587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansuri, S.M.; Gautam, P.V.; Jain, D.; Nickhil, C. Pramendra Computer Vision Model for Estimating the Mass and Volume of Freshly Harvested Thai Apple Ber (Ziziphus mauritiana L.) and Its Variation with Storage Days. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 305, 111436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivabalan, K.; Sunil, C.K.; Venkatachalapathy, N. Mass Modeling of Coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) with Physical Characteristics. Int. J. Chem. Stud. 2019, 7, 5067–5072. [Google Scholar]

| Attributes | Algerie | Claudia | Golden Nugget | Nespolone di Trabia | Peluche | Virticchiara |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dg | 38.35 ± 3.95 | 43.09 ± 3.96 * | 41.53 ± 4.56 | 41.51 ± 4.45 | 48.56 ± 5.52 ** | 39.54 ± 3.77 |

| Ψ | 0.90 ± 0.05 | 0.86 ± 0.04 | 0.92 ± 0.06 * | 0.92 ± 0.05 * | 0.77 ± 0.06 ** | 0.89 ± 0.06 |

| DL | 42.66 ± 4.56 | 50.12 ± 5.06 * | 45.05 ± 5.34 | 45.29 ± 5.99 | 63.31 ± 7.36 ** | 44.48 ± 4.88 |

| DT1 | 37.50 ± 4.23 | 41.53 ± 4 | 41.23 ± 4.61 | 41.16 ±4.36 | 43.90 ± 5.94 | 38.81 ±3.94 |

| DT2 | 35.34 ± 4.02 | 38.54 ± 4.05 | 38.70 ± 4.9 | 38.46 ± 3.88 | 41.42 ± 5.44 * | 35.96 ± 4.05 |

| V | 32.13 ± 9.73 | 45.41 ± 11.83 | 39.91 ±12.57 | 41.60 ±12.53 | 63.44 ± 12 ** | 35.57 ±9.35 |

| V(osp) | 32.33 ± 9.72 | 46.24 ± 12.03 | 41.34 ± 12.94 | 41.53 ± 12.96 | 66.12 ± 22 ** | 35.82 ± 8.67 |

| V(ellip) | 30.45 ± 9.23 | 42.93 ± 11.46 | 38.84 ± 12.6 | 38.70 ±11.85 | 62.29 ± 21.6 ** | 33.19 ± 8.21 |

| AR | 1.14 ± 0.1 | 1.21 ± 0.1 | 1.10 ± 0.1 | 1.10 ± 0.08 | 1.46 ± 0.12 * | 1.15 ± 0.17 |

| Fruit weight | 33.36 ± 10 | 46.56 ± 12.07 * | 42.23 ± 13.2 | 42.80 ± 12.48 | 63.3 ± 20.88 ** | 37.45 ± 9.37 |

| Statistical Parameters | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model (Attributes) | Model Equation | R2 | RMSE | MBE |

| Cubic (DL) | −57.8142 + 3.3044 DL − 0.0368 DL2 + 0.0002 DL3 | 0.69 | 9.23 | 2.01 × 10−13 |

| P. Inverse3 (DT1) | 0.85 | 6.43 | −2.27 × 10−12 | |

| Cubic (DT2) | −9.0169 + 1.2869 DT2 − 0.04 DT22 + 0.0011 DT23 | 0.88 | 5.86 | 1.23 × 10−13 |

| Quadratic (V(ellip)) | 0.655 + 1.0863 V(ellip) − 0.0003 V(ellip)2 | 0.98 | 2.61 | 9.92 × 10−15 |

| Cubic (V(osp)) | 2.7069 + 0.8904 V(osp) − 0.002 V(osp)2 + 0.011 V(osp)3 | 0.95 | 3.56 | 3.40 × 10−14 |

| Regression Constants | Statistical Parameters | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variety | Model (Attributes) | a | b | c | d | R2 | RMSE | MBE |

| Algerie | Cubic (V(ellip)) | 6.584 | 0.463 | 0.017 | −2 × 10−4 | 0.98 | 1.46 | −3.70 × 10−15 |

| Quadratic (V(ellip)) | 1.8674 | 0.958 | 0.0019 | - | 0.98 | 1.48 | 5.63 × 10−15 | |

| Linear (V(ellip)) | 0.0203 | 1.081 | - | - | 0.98 | 1.49 | 3.66 × 10−15 | |

| Linear (V(osp)) | 0.1458 | 1.0144 | - | - | 0.96 | 2.12 | −1.13 × 10−16 | |

| P. Inverse3 (DT2) | 297.67 | −17,424.11 | 348,019 | −2,244,065 | 0.94 | 2.51 | 7.94 × 10−14 | |

| Linear (DT2) | −52.6804 | 2.422 | - | - | 0.93 | 2.62 | −2.44 × 10−14 | |

| Cubic (DT1) | 53.3759 | −3.8646 | 0.09 | −3 × 10−4 | 0.92 | 2.76 | −4.27 × 10−14 | |

| P. Inverse2 (DT1) | 269.24 | −14,284.6 | 202,224 | - | 0.92 | 2.86 | 2.51 × 10−13 | |

| Linear (DT1) | −51.95 | 2.2637 | - | - | 0.90 | 3.19 | 1.47 × 10−14 | |

| Claudia | Cubic (V(ellip)) | −2.33 | 1.289 | −0.0049 | - | 0.97 | 2.18 | 1.20 × 10−14 |

| Linear (V(ellip)) | 1.6795 | 1.034 | - | - | 0.97 | 2.19 | 7.34 × 10−15 | |

| Cubic (V(osp)) | −1.55 | 1.235 | −0.0068 | 0.0004 | 0.91 | 3.54 | 3.92 × 10−14 | |

| Linear (V(osp)) | 1.769 | 0.958 | - | - | 0.91 | 3.55 | 4.16 × 10−14 | |

| P. Inverse3 (DT2) | 332.15 | −18,512.86 | 321,022.65 | −1,276,363 | 0.90 | 3.75 | 6.44 × 10−14 | |

| Linear (DT2) | −62.1645 | 2.7275 | - | - | 0.90 | 3.76 | −5.60 × 10−14 | |

| Cubic (DT1) | −153.464 | 11.3283 | −0.3782 | −0.003 | 0.90 | 3.84 | 7.46 × 10−15 | |

| Linear (DT1) | −67.1645 | 2.7275 | - | - | 0.83 | 4.96 | −5.50 × 10−14 | |

| Cubic (DL) | 303.6252 | −20.2291 | 0.4578 | −0.003 | 0.82 | 5.15 | 2.63 × 10−14 | |

| Linear (DL) | −51.3776 | 1.9449 | - | - | 0.67 | 6.93 | 7.47 × 10−13 | |

| Golden nuggets | Cubic (V(ellip)) | −2.1055 | 1.328 | −0.074 | 0.001 | 0.97 | 2.35 | 2.23 × 10−14 |

| Linear (V(ellip)) | 1.4713 | 1.0332 | - | - | 0.97 | 2.35 | 1.70 × 10−14 | |

| Cubic (V(osp)) | −4.763 | 0.9384 | −0.0112 | 0.004 | 0.95 | 2.97 | 1.80 × 10−15 | |

| Quadratic (V(osp)) | 1.6004 | 0.9384 | 0.0006 | - | 0.95 | 2.99 | 3.73 × 10−15 | |

| Linear (V(osp)) | 0.4539 | 0.9955 | - | - | 0.95 | 2.99 | 8.53 × 10−15 | |

| P. Inverse3 (DT2) | 893.7261 | −78,032.20 | 2,355,205 | −23,855,109 | 0.92 | 3.63 | 1.55 × 10−13 | |

| P. Inverse3 (DT1) | 665.8907 | −57,834.986 | 1,772,408.4 | −18,622,981 | 0.87 | 4.71 | −7.18 × 10−14 | |

| Linear (DT1) | −67.6165 | 2.6489 | - | - | 0.85 | 5.02 | 2.59 × 10−14 | |

| Linear (DT2) | −54.3336 | 2.4792 | - | - | 0.84 | 5.21 | −2.66 × 10−14 | |

| Cubic (DL) | −193.0831 | 12.0711 | −0.2326 | 0.00188 | 0.72 | 6.90 | 1.82 × 10−13 | |

| Nespolone di Trabia | Cubic (V(ellip)) | −3.355 | 1.5413 | −0.014 | 0.0001 | 0.98 | 1.63 | 4.69 × 10−15 |

| Linear (V(ellip)) | 1.8173 | 1.0433 | - | - | 0.98 | 1.68 | 5.83 × 10−15 | |

| Cubic (V(osp)) | −0.4581 | 1.2918 | −0.0099 | 0.0001 | 0.95 | 2.64 | 1.67 × 10−16 | |

| Cubic (DT1) | 6.7845 | −0.6501 | 0.0243 | 0.003 | 0.92 | 3.50 | −4.290 × 10−15 | |

| Quadratic (DT1) | 24.0347 | −1.9873 | 0.0584 | - | 0.92 | 3.50 | 5.429 × 10−15 | |

| Linear (DT1) | −69.8441 | 2.722 | - | - | 0.90 | 3.83 | −2.00 × 10−14 | |

| Quadratic (DT2) | −52.9953 | 1.8906 | 0.015 | - | 0.90 | 3.87 | 1.97 × 10−14 | |

| Linear (DT2) | −75.2735 | 3.0543 | - | - | 0.90 | 3.88 | 3.25 × 10−14 | |

| Cubic (DL) | −169.2834 | 12.0549 | −0.269 | 0.0022 | 0.80 | 5.52 | −5.35 × 10−14 | |

| Linear (DL) | −41.5972 | 1.8501 | - | - | 0.79 | 5.67 | −3.01 × 10−15 | |

| Peluche | Quadratic (V(ellip)) | −8.0154 | 1.3202 | −0.0026 | - | 0.97 | 3.41 | 4.89 × 10−15 |

| Linear (V(ellip)) | 3.5717 | 0.9503 | - | - | 0.97 | 3.66 | 4.25 × 10−15 | |

| Cubic (V(osp)) | 7.2528 | 0.6088 | 0.006 | - | 0.95 | 4.57 | −2.69 × 10−14 | |

| Linear (V(osp)) | 5.5 | 0.866 | - | - | 0.94 | 4.96 | −1.10 × 10−15 | |

| Cubic (DT2) | 142.1188 | −11.683 | 0.333 | −0.002 | 0.91 | 6.29 | 9.72 × 10−14 | |

| Quadratic (DT2) | −32.8939 | 0.9851 | 0.0314 | - | 0.91 | 6.31 | −1.93 × 10−14 | |

| Linear (DT2) | −88.4103 | 3.6498 | - | - | 0.90 | 6.39 | −5.04 × 10−14 | |

| Cubic (DT1) | 362.901 | −25.8721 | 0.6274 | −0.0044 | 0.89 | 6.83 | −6.09 × 10−13 | |

| Linear (DT1) | −82.3454 | 3.3056 | - | - | 0.88 | 7.06 | −9.26 × 10−15 | |

| Cubic (DL) | 1164.12 | −54.6319 | 0.8588 | −0.0043 | 0.55 | 13.82 | −1.41 × 10−12 | |

| Virticchiara | P. Inverse3 (DT2) | 564.38 | −44,953.31 | 1,286,677 | −12,709,763 | 0.92 | 2.66 | −1.08 × 10−13 |

| Cubic (DT2) | −250.711 | 22.107 | −0.6227 | 0.0064 | 0.92 | 2.68 | −9.85 × 10−13 | |

| Quadratic (V(ellip)) | 2.7468 | 0.9289 | 0.0027 | - | 0.92 | 2.71 | 1.40 × 10−15 | |

| Linear (V(ellip)) | 0.5092 | 1.0919 | - | - | 0.91 | 2.72 | 4.73 × 10−15 | |

| Linear (DT2) | −42.5747 | 2.2062 | - | - | 0.91 | 2.77 | −3.75 × 10−14 | |

| Cubic (DT1) | 893.5024 | −78.157 | 2.2504 | −0.0207 | 0.87 | 3.41 | 1.45 × 10−12 | |

| Cubic (V(osp)) | 19.6474 | −1.5186 | 0.0956 | −0.0207 | 0.84 | 3.71 | −3.50 × 10−14 | |

| Linear (V(osp)) | 1.8478 | 0.9744 | 0.81 | 4.02 | −3.29 × 10−14 | |||

| Inverse3 (DL) | −40.0215 | 12,951.08 | −583,873.36 | 7,171,246 | 0.41 | 7.11 | 2.19 × 10−13 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gugliuzza, G.; Massaad, M.; Tomasino, G.; Farina, V. Mass Modeling of Six Loquat (Eriobotrya japonica Lindl.) Varieties for Post-Harvest Grading Based on Physical Attributes. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1445. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121445

Gugliuzza G, Massaad M, Tomasino G, Farina V. Mass Modeling of Six Loquat (Eriobotrya japonica Lindl.) Varieties for Post-Harvest Grading Based on Physical Attributes. Horticulturae. 2025; 11(12):1445. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121445

Chicago/Turabian StyleGugliuzza, Giovanni, Mark Massaad, Giuseppe Tomasino, and Vittorio Farina. 2025. "Mass Modeling of Six Loquat (Eriobotrya japonica Lindl.) Varieties for Post-Harvest Grading Based on Physical Attributes" Horticulturae 11, no. 12: 1445. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121445

APA StyleGugliuzza, G., Massaad, M., Tomasino, G., & Farina, V. (2025). Mass Modeling of Six Loquat (Eriobotrya japonica Lindl.) Varieties for Post-Harvest Grading Based on Physical Attributes. Horticulturae, 11(12), 1445. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121445