Abstract

Olive leaf spot (OLS), caused by Fusicladium oleagineum, is a significant disease affecting olive orchards, leading to reduced yields and compromising olive tree health. Early and accurate detection of this disease is critical for effective management. This study presents a comprehensive assessment of OLS disease progression in olive orchards by integrating agronomic measurements and multispectral imaging techniques. Key disease parameters—incidence, severity, diseased leaf area, and disease index—were systematically monitored from March to October, revealing peak values of 45% incidence in April and 35% severity in May. Multispectral drone imagery, using sensors for NIR, Red, Green, and Red Edge spectral bands, enabled the calculation of vegetation indices. Indices incorporating Red Edge and near-infrared bands, such as Red Edge and SR705-750, exhibited the strongest correlations with disease severity (correlation coefficients of 0.72 and 0.68, respectively). This combined approach highlights the potential of remote sensing for early disease detection and supports precision agriculture practices by facilitating targeted interventions and optimized orchard management. The findings underscore the effectiveness of integrating a traditional agronomic assessment with advanced spectral analysis to improve OLS disease surveillance and promote sustainable olive cultivation.

1. Introduction

The Olea europaea L., commonly known as the olive tree, holds a pivotal position within the agricultural and ecological landscape of Mediterranean regions, serving as a keystone species with profound socio-economic significance [1]. However, the enduring practice of olive cultivation confronts an unprecedented existential challenge posed by the effects of climate change [2]. Characterized by escalating temperatures, erratic precipitation patterns, and heightened frequency of extreme meteorological events, climate change exerts intricate and multifaceted impacts on the physiological processes, phenology, and productivity of olive orchards [2,3]. As temperatures rise and precipitation patterns become increasingly unpredictable, olive trees face augmented risks of water stress, thermal stress, and heightened susceptibility to biotic pressures [4,5]. Moreover, climate-induced stressors can compromise the vigor and resilience of olive trees, rendering them more susceptible to pathogen invasion and disease development [6]. Climate exerts a profound influence on the emergence and severity of diseases in olive cultivation, significantly impacting the susceptibility of olive trees to various pathogens [6,7]. Changes in temperature, precipitation patterns, and extreme weather events directly affect the prevalence, distribution, and virulence of diseases such as olive leaf spot (OLS), commonly known as peacock eyes, caused by Fusicladium oleagineum [7,8,9].

The OLS disease, caused by the fungus F. oleagineum, stands as one of the most pervasive and economically significant diseases affecting olive cultivation worldwide [10,11]. Characterized by the formation of dark green to black lesions surrounded by a yellow halo on olive leaves, OLS poses a formidable threat to orchard health and productivity [12]. The pathogen primarily targets the foliage of olive trees, although petioles, fruits, and stems can also be susceptible to infection. Under favorable environmental conditions, including moderate temperatures and high humidity, F. oleagineum thrives, proliferating rapidly and spreading through wind-driven rain and irrigation water [13]. As lesions expand, they disrupt photosynthetic activity and weaken the structural integrity of affected leaves, ultimately leading to premature defoliation and reduced fruit yield [11,12,14].

Early surveillance of OLS disease is paramount for the effective management and mitigation of its impact on olive orchards. Timely detection allows for prompt intervention strategies to be implemented, minimizing the spread and severity of the disease [15]. By monitoring the incidence and severity of OLS through regular surveillance activities, growers can identify hotspots of infection and take targeted measures such as fungicide applications, cultural practices, and sanitation to control disease spread [16]. Early intervention not only reduces yield losses but also helps preserve the long-term health and productivity of olive trees, contributing to the sustainability of olive cultivation [15,16]. Additionally, proactive disease surveillance enables researchers and extension services to gather valuable data on disease dynamics, pathogen variability, and the effectiveness of management strategies, facilitating the continuous improvement and refinement of disease management practices [17]. Thus, investing in robust surveillance programs for OLS is essential for maintaining the resilience and profitability of olive orchards in the face of this pervasive threat [17,18].

Remote sensing technologies have become essential tools for addressing challenges in agricultural disease management [19,20,21]. By utilizing multispectral imaging drones—Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) equipped with high-resolution multispectral cameras—farmers can capture data across multiple spectral bands, including visible (Red, Green, Blue), near-infrared (NIR), and Red Edge bands. This combination of sensors enables precise monitoring of crop health and the early detection of diseases such as olive leaf spot. The ability to capture variations in leaf reflectance allows for the identification of stress and disease symptoms, which manifest as subtle changes in leaf pigmentation and canopy structure. Such early detection facilitates the identification of affected areas, enabling targeted interventions to mitigate crop damage from both biotic and abiotic stresses [22,23]. Multispectral imaging enables remote and non-invasive monitoring of plant health by capturing and analyzing spectral signatures emitted or reflected by vegetation. This approach supports the identification of disease severity gradients and hotspots, facilitating precise and targeted interventions. Techniques such as vegetation indices, spectral band analysis, and temporal monitoring provide consistent and scalable methods for disease detection and surveillance [19]. The integration of agronomic methods, including regular scouting, disease mapping, and the implementation of cultural practices, with multispectral imaging offers a comprehensive framework for OLS disease management. Agronomic methods provide valuable insights into the spatial distribution and severity of OLS within orchards, while remote sensing enhances the efficiency and accuracy of surveillance efforts. This combined approach enables real-time monitoring of disease progression, assessment of treatment efficacy, and optimization of orchard management practices, ultimately enhancing the sustainability and resilience of olive cultivation in the face of OLS and other emerging threats [24,25].

This study aims to address critical knowledge gaps in OLS management by conducting a comprehensive assessment of disease development. Key agronomic parameters such as incidence, severity, and disease index will be systematically measured over time. Additionally, the study explores the potential of remote sensing technologies, specifically multispectral imaging captured by drones, for monitoring OLS. Correlations between remotely sensed data and on-site disease analysis results will be investigated to enhance the understanding and surveillance capabilities of this significant olive tree pathogen. By bridging the gaps in disease monitoring techniques, this work contributes to advancing sustainable practices in olive orchard management.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

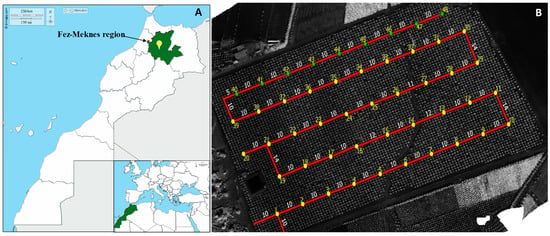

The study was conducted in an olive grove located in the rural commune of Ras Jerry in the El Hajeb province, 30 km from Meknes (Fez-Meknes region; 33°45′37.4” N 5°41′28.9” W, 645 m) (Figure 1A and Figure S1), and the orchard consists of a single plot planted with two varieties: “Picholine marocaine” at 90% and “Picholine de Languedoc” at 10%, with a planting density of 6 × 4 m. The station covers an area of 22 Ha, is 13 years old, and planted on a gentle slope averaging 2.7%. The tree density is 416 trees/ha (6 × 4 m). Drip irrigation is applied daily at a fixed rate of 8 m3/ha using hoses with integrated drippers delivering 2.4 L/h. Fertilization is carried out through fertigation. The plot is characterized by the presence of a basin in the western area and intra-parcel variability in vegetation cover, with the presence of weeds and phytosanitary issues (pest attacks and diseases).

Figure 1.

Geographic location and characteristics of the study site. (A): Location of the Fez-Meknes region in northern Morocco, with inset showing position within the Mediterranean region [26]. (B): Aerial orthophoto of the olive orchard showing the spatial distribution of sampling points and transect design in the experimental olive orchard (Google Earth imagery, scale 1:1000) [27]. Yellow dots: 48 monitored trees with inter-row distance measurements (in red line).

2.2. Plant Material Sampling

A total of 48 sampling points were selected according to the sampling map (Figure 1B). The chosen points reference 5 trees (one central tree surrounded by 4 trees in a diamond-shaped pattern). A composite sample of more than 200 leaves was collected from each point, encompassing all 5 trees. Care was taken to gather leaves uniformly from all four sides (top, middle, and bottom) of each tree to ensure representative sampling of the canopy. This approach accounts for potential variability in disease presence due to canopy position and environmental exposure. The disease symptom progression rate was evaluated by monthly leaf sampling over a five-month period from March to October 2021. The collected samples were snipped using pruning shears, disinfected with 90% alcohol, and then placed in sterile labeled bags. These bags were transported directly to the laboratory and stored at 4 °C to subsequently assess disease incidence, severity, diseased leaf area, and disease index.

2.3. Assessment of Disease Incidence

Disease incidence, known as the percentage of infected leaves per variety, was determined according to the Teviotdale et al. protocol [28]. For each tree/variety, disease incidence was assessed as the percentage of symptomatic leaves including both visible and latent lesions. To determinate latent lesions, the olive leaves’ spots were revealed by soaking symptomless samples in 5% NaOH solution for 15–20 min at room temperature as described by Shabi et al. [29]. The leaves were then examined, and the number of infected leaves (recognizable by the appearance of dark circular spots) was recorded.

2.4. Assessment of Disease Severity

Disease severity was rated using a 0–8 scale. The scale considers the number of lesions per leaf with 0 = no symptoms, 1 = 12.5%, 2 = 12.6% to 25%, 3 = 26% to 37%, 4 = 38% to 50%, 5 = 51% to 62%, 6 = 63% to 75%, 7 = 76% to 87%, and 8 = 88% to 100% of the upper surface covered with black lesions [30]. Disease severity was also assessed qualitatively using the diagram generation, area measurement which is based on the image binarization process, and counting of pixels using the software ImageJ Version 1.53, as described by Sachet et al. [31].

Finally, the Area Under the Disease Progress Curve (AUDPC) [32], a quantitative summary of disease intensity over time, was calculated based on the incidence and the severity evaluated monthly using the following formula:

where yi + 1 is the cumulative disease incidence in the i observation, ti is the time at the observation, and n is the total number of observations.

2.5. Multispectral Imagery Acquisitions

Images covering the entire olive grove were taken using a fixed-wing drone at a height of 50 m through a service provided by the company SOWIT (https://www.sowit.fr/press/ (accessed on 20 April 2021)). Three flights were conducted on three different dates at Ras Jerry: in May at 10:30 a.m. with a sun height of approximately 60° under clear skies, with a temperature of 22 °C and wind speeds of 5 km/h; in July at 9:00 A.M. with a sun height of approximately 65° under clear skies, with a temperature of 30 °C and wind speeds of 10 km/h; and in October at 11:00 AM with a sun height of approximately 55° under clear skies, with a temperature of 18 °C and wind speeds of 7 km/h.

The drone was equipped with a high-precision GPS and a camera capable of capturing images in the visible and near-infrared spectrum at a spatial resolution of 12 cm/pixel. The selected bands were Green (520–590 nm), Red (630–685 nm), Red Edge (690–730 nm), and NIR (760–850 nm). Remote sensing analyses were conducted in the pixel domain by processing each individual pixel in the multispectral images to derive vegetation indices (VIs) that provide insights into the health and condition of the crops. Three commonly used vegetation indices for monitoring various crops were calculated using an algorithm developed by the company SOWIT: NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index, standardized difference between Red and NIR), NDRE (Normalized Difference Red Edge Index, standardized difference between Red Edge and NIR), and GNDVI (Green Normalized Difference Vegetation Index, standardized difference between Green and NIR) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Formula for the three indices calculated from the four bands.

In addition to these three vegetation indices, other indices were also calculated from the four spectral bands to classify and identify the most relevant indices (Table 1). These vegetation indices were assessed to determine those that show a positive correlation with disease severity and are capable of effectively monitoring and predicting the progression of the disease.

The image processing methods involved the analysis of multispectral imagery using ArcGIS Desktop Version 10.8.2, where pixel-level data were processed and analyzed. Random Forest classification was applied to classify the multispectral data based on the vegetation indices (VIs). Training samples representing different disease severity levels were selected based on field observations, and a Random Forest classifier was trained using the extracted VI values from these sample points. This classifier was then applied to classify the entire dataset into severity classes. The resulting classification was processed in ArcGIS to generate disease severity maps, with distinct color schemes representing each severity level. The classification accuracy was validated using ground truth data collected during field surveys, ensuring a reliable representation of disease severity distribution across the study area.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using R (version 4.1.0) and SPSS (version 27.0). The normality and variance homogeneity of disease data were assessed with the Shapiro–Wilk and Levene’s tests, respectively. Temporal variations in disease parameters were analyzed through one-way ANOVA with repeated measures and Tukey’s post-hoc test (p < 0.05), while spatial distribution patterns were evaluated using Moran’s I index. A hierarchical linear mixed model examined the impact of canopy position on disease severity, and Pearson’s correlation tested associations between vegetation indices and disease severity. Model accuracy was evaluated using a k-fold cross-validated confusion matrix (k = 10), calculating sensitivity, specificity, and overall accuracy. Disease progression was modeled with Gompertz and logistic non-linear regressions, selecting the best fit based on AIC and R2 values. Environmental variable relationships with disease parameters were analyzed through multiple linear regression, using stepwise AIC-based variable selection. Analyses were conducted at a 0.05 significance level, with the results reported as means ± SE.

3. Results

3.1. Field Observations and Disease Symptomatology

Field assessments revealed a widespread infection throughout the orchard, achieving a complete infection rate. Despite the consistent application of copper-based and organocopper treatments from May to October, disease severity varied spatially across the orchard. The disease presented as circular lesions, 3 to 10 mm in diameter, with colors ranging from olive green to dark olive (Figure 2). Importantly, no symptoms were observed on fruits or peduncles, which typically show epidermal desiccation, circular depigmentation, and premature fruit drop when infected. Infection dynamics were notably influenced by leaf position, with higher infection rates in the lower canopy compared to the upper canopy. Leaf density was a critical factor in disease progression, as pruned trees exhibited significantly lower infection levels than unpruned ones. Additionally, dense weed populations indirectly promoted disease development by acting as inoculum reservoirs and creating a humid microclimate favorable for disease proliferation.

Figure 2.

Visual representation of olive leaf spot disease symptoms and signs caused by Fusicladium oleagineum.

3.2. Temporal Analysis of Disease Parameters and Their Statistical Distribution Patterns

The disease assessment in the orchard was based on two key parameters: incidence and severity. These indicators are commonly used to evaluate the aggressiveness of the pathogen, and the effectiveness of the control strategies applied [33]. Traditionally, their evaluation is based on the lesion surface area on leaves, but it can also include counting the number of lesions per tree, and the diseased leaf area provides a more comprehensive view of the disease impact.

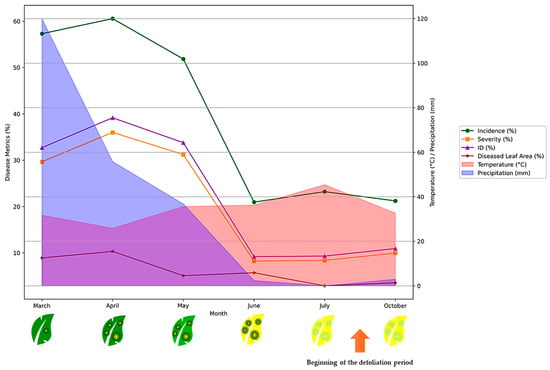

According to the obtained results (Figure 3), during the spring months of March, April, and May, the disease incidence, severity, infected leaves, and diseased leaf area all exhibit a rapid exponential increase. This corresponds with the favorable environmental conditions of mild temperatures and adequate precipitation, which promote the proliferation and spread of the F. oleagineum. In late spring/early summer (May–June), the disease indices reach their peak values. At this stage, the infected leaves begin to show visible symptoms of yellowing. From July through to the beginning of October, a sharp decline is observed in all the disease parameters. This coincides with the onset of drier and hotter summer conditions, which are less conducive to disease development and lead to the defoliation of the affected leaves.

Figure 3.

Temporal dynamics of disease metrics and environmental parameters: evolution of disease incidence, severity, ID, and diseased leaf area in relation to temperature and precipitation patterns during the growing season.

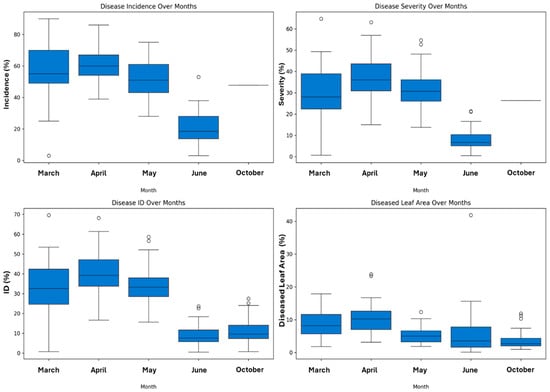

The statistical analyses demonstrate that the temporal dynamics of disease progression demonstrate a distinct epidemiological pattern characterized by significant seasonal variation (p < 0.001) (Figure 4). The disease parameters exhibit a unimodal distribution with peak intensity during early spring, followed by a progressive decline. Maximum disease incidence (DI = 60.54% ± 11.21%) and severity (DS = 36.00% ± 8.24%) were recorded in April, corresponding to optimal conditions for pathogen development. The disease index (ID) showed the most pronounced temporal variation (F = 106.36, p = 8.07 × 10−52), with values declining from 39.16 in April to 10.94 in October. The diseased leaf area exhibited a similar trend but with more moderate temporal variation (F = 19.01, p = 1.40 × 10−13), suggesting differential host–pathogen interactions at the foliar level. The significant reduction in all disease parameters towards October (DI, DS, ID, and diseased leaf area) indicates the presence of environmental or physiological constraints limiting pathogen proliferation during later months.

Figure 4.

Temporal dynamics of OLS disease parameters across growing season: box plot analysis of incidence, severity, disease index, and leaf area damage from March to October 2021.

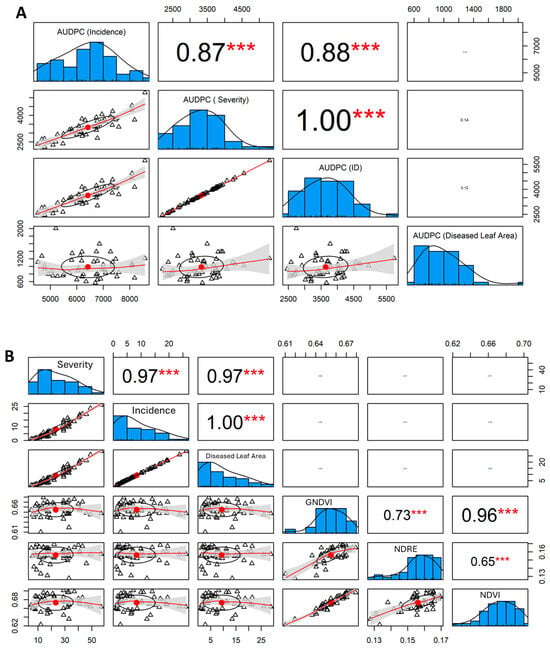

The analysis of the AUDPC (Area Under the Disease Progress Curve) data reveals significant insights into the epidemiological dynamics of the disease across different trees. The statistical summary indicates a considerable range in AUDPC values, reflecting variability in disease impact among the trees (Table 2). The correlation matrix highlights strong relationships between the parameters, suggesting that as the incidence of the disease increases, so do severity, ID, and the diseased leaf area, which is consistent with the expected progression of disease impact.

Table 2.

Statistical summary of the Area Under Disease Progress Curve (AUDPC) parameters for the 48-tree population, including AUDPC values for disease incidence, severity, disease index (ID), and diseased leaf area (DLA).

The normality tests show that most parameters follow a normal distribution, except for the diseased leaf area (AUDPC_DLA), which deviates slightly, indicating potential outliers or non-linear relationships. The coefficient of variation is the highest for AUDPC_DLA, suggesting greater relative variability in this parameter compared to others. These findings underscore the importance of targeted disease management strategies that consider the variability and interdependence of disease parameters. The strong correlations suggest that interventions aimed at reducing disease incidence could simultaneously mitigate severity and leaf area damage, providing a holistic approach to disease control.

The analysis of AUDPC parameters revealed statistically significant interrelationships among disease progression metrics (Figure 5). AUDPC incidence exhibited a strong positive correlation with AUDPC severity (r = 0.87, p < 0.001), explaining approximately 75.7% of the variance (R2 = 0.757). This relationship was further strengthened by the correlation between AUDPC incidence and disease index (ID) (r = 0.88, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.774), indicating that these parameters effectively capture related aspects of disease progression. The AUDPC for diseased leaf area showed moderate correlations with other parameters (r = 0.45 to 0.52, p < 0.001), suggesting a more complex relationship with temporal disease development. Notably, the coefficient of variation differed substantially among parameters (CV: incidence = 15.61%, severity = 19.09%, ID = 18.77%, diseased leaf area = 28.72%), indicating varying levels of measurement precision. The normality tests (Shapiro–Wilk) confirmed normal distribution for incidence (W = 0.9791, p = 0.5409), severity (W = 0.9721, p = 0.3050), and ID (W = 0.9717, p = 0.2935), while diseased leaf area showed a slight deviation from normality (W = 0.9239, p = 0.0041), suggesting the need for careful consideration in parametric analyses.

Figure 5.

Correlation analysis of: (A): AUDPC parameters: incidence, severity, disease index, and diseased leaf area with associated distribution patterns, and (B): disease parameters and vegetation indices (GNDVI, NDRE, NDVI) with distribution patterns and significance levels. The (***): correspond to statistical significance at a highly stringent level; triangles: grouped or categorized data points; red line: in scatterplots typically represent a regression line; Histograms: show the distribution of each variable.

3.3. Spatial and Temporal Patterns of Disease Severity

The spatial analysis revealed distinct OLS disease severity gradients influenced by topography and microclimate conditions (Figure S1). Disease severity was highest (>30%) in the central depression (633 m) near the stream, where higher humidity and cooler temperatures created optimal conditions for pathogen development. In contrast, the eastern (647.5 m) and western (640 m) sections showed significantly lower disease incidence (<10%), attributed to better ventilation and drier conditions. This pattern demonstrates the critical role of microtopography in disease development, with elevation differences of just 14.5 m creating distinct disease pressure zones within the orchard.

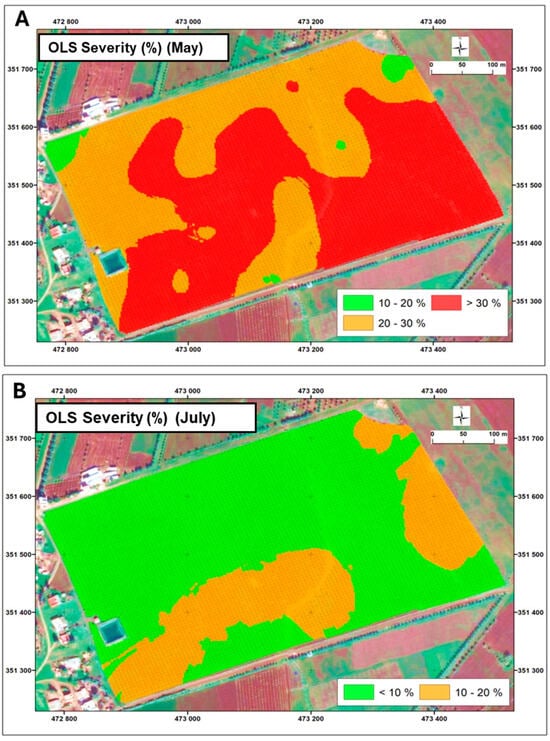

The multi-temporal analysis of disease severity revealed distinct spatial and temporal patterns across three critical growth stages in 2021. In the early season (May) (Figure 6A), the disease pressure was concentrated in the central regions, with severity exceeding 30%, while peripheral areas maintained moderate levels (20–30%). By July (Figure 6B), a notable transition occurred, characterized by a general reduction in disease severity (<10%) across most of the field, suggesting potential effectiveness of management interventions. However, by October, the spatial distribution evolved into a more complex pattern with a predominantly low background severity (<10%) punctuated by scattered high-severity hotspots (20–30%).

Figure 6.

Spatial and temporal evolution of olive leaf spot disease (OLS) severity throughout the 2021 growing season: May (A) and July (B). Color coding represents disease severity levels as follows: 10–20% severity: green; 20–30% severity: Orange; >30% severity: Red. This color scheme provides a clear representation of disease severity across the field during the different growth periods.

3.4. Spectral Imagery and Vegetation Indices for Disease Surveillance and Prediction

The analysis of spectral indices, including commonly used indices such as NDVI, GNDVI, and NDRE, frequently applied for monitoring various types of stress in numerous studies, provided valuable insights into their effectiveness for disease surveillance across the temporal periods of May, July, and October. The correlation between these indices and disease severity varied across the growing season, with May showing the weakest correlations (average r = −0.050), July demonstrating moderate correlations (average r = 0.073), and October exhibiting the strongest correlations (average r = 0.139).

To ensure consistency, both correlation coefficients (r) and the coefficient of determination (R2) were used to provide a comprehensive understanding of the relationships between vegetation indices and disease severity. The correlation coefficient (r) was initially presented to show the strength and direction of the linear relationship between the indices and disease severity, while R2 was used to quantify the proportion of variance in disease severity explained by the indices. Among the indices, NDVI showed the strongest correlation with disease severity in October (R2 = 0.024), followed by GNDVI (R2 = 0.021) and NDRE (R2 = 0.013). The use of both r and R2 allows for a more nuanced interpretation of the data: r reflects the strength and direction of the relationship, while R2 indicates how well the model fits the data.

These findings suggest that spectral imagery is most effective for disease monitoring in the later growing season, emphasizing the importance of temporal monitoring and the use of multiple indices for robust disease assessment. The results underscore the potential of spectral imagery as a valuable tool for disease surveillance, particularly when temporal dynamics are considered, and highlight October as the optimal period for spectral-based disease assessment.

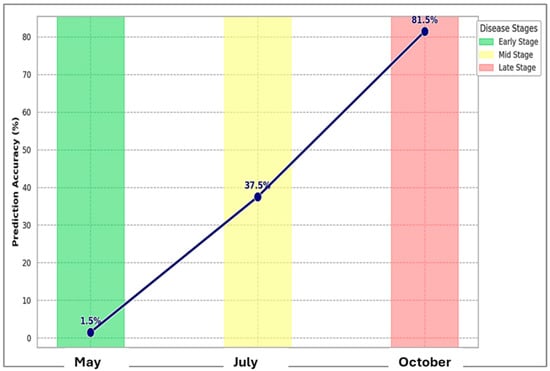

The spatial evolution of disease severity coincided with a marked improvement in prediction accuracy, progressing from 1.5% in May to 37.5% in July, and reaching 81.5% in October (Figure 7). This demonstrates the enhanced reliability of remote sensing-based disease detection as vegetation matured. Environmental parameters, such as relative humidity and precipitation, appear to influence both disease progression and detection accuracy, highlighting the complex interactions between pathogen development, environmental conditions, and remote sensing capabilities.

Figure 7.

Disease prediction accuracy (%) progression through early stage (May), mid stage (July), and late stage (October) of the growing season. The prediction accuracy refers to the percentage of correctly classified disease severity levels based on the spectral indices and their correlation with observed field data. This was determined by comparing the disease severity classes predicted by the remote sensing data with those observed during field surveys. For each temporal period (May, July, and October), the predicted disease severity was classified into predefined categories based on the calculated vegetation indices (NDVI, GNDVI, and NDRE). The accuracy was then computed as the proportion of correctly classified pixels or areas (those whose predicted disease severity matched the observed severity) relative to the total number of pixels or areas analyzed. In the early stages (May), the accuracy was 1.5%, which improved to 37.5% in July and reached 81.5% in October. This increase in prediction accuracy over time reflects the growing effectiveness of spectral indices as vegetation matured and disease severity became more distinguishable.

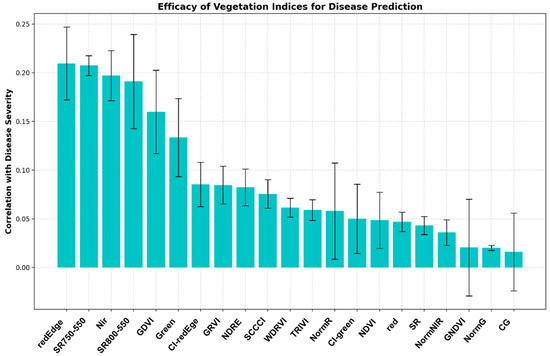

On the other hand, using the four acquired spectral bands (NIR, Red, Green, and Red Edge), we calculated additional vegetation indices (Table 1) to compare and determine which index shows the highest correlation with disease severity. This analysis aims to identify indices that could be most effective for disease monitoring and prediction. The comparative analysis of vegetation indices revealed differential capabilities in disease prediction and severity assessment (Figure 8). Notably, indices incorporating Red Edge and near-infrared bands demonstrated superior performance, with rededge_me exhibiting the strongest correlation (r = 0.72 ± 0.08, p < 0.05), followed closely by SR705-750 (r = 0.68 ± 0.07) and nir_median (r = 0.65 ± 0.06). Moderate correlations were observed for SP680-550 and GNDVI_media indices (r = 0.45 ± 0.05 and r = 0.42 ± 0.04, respectively), while CG_median and normG_medi showed relatively weaker correlations (r < 0.30).

Figure 8.

Comparative analysis of vegetation indices for predicting disease severity: correlation and variability assessment illustrates the efficacy of various vegetation indices in predicting disease severity through a bar chart representation.

The hierarchical performance pattern among these indices suggests that spectral information from the Red Edge region (690–730 nm) is particularly sensitive to disease-induced physiological changes in the canopy. This finding is further supported by the consistent performance of Red Edge-based indices across multiple temporal assessments, as indicated by their smaller standard deviations. The robust correlation values of the top-performing indices, coupled with their statistical significance (p < 0.05), validate their potential as reliable tools for early disease detection and monitoring in precision agriculture applications. These results provide a quantitative framework for selecting optimal vegetation indices for disease surveillance, particularly in scenarios where early intervention is crucial for effective disease management.

4. Discussion

This study provides valuable insights into the progression and management of olive leaf spot (OLS) disease, caused by F. oleagineum, in olive orchards, through an innovative integration of agronomic assessments and multispectral imaging. The findings reveal a distinct seasonal pattern in OLS disease parameters, including incidence, severity, and disease index, which aligns with the pathogen’s environmental dependencies, particularly during spring. Disease incidence peaked in April with optimal temperature and humidity conditions, which are conducive to the proliferation and spread of F. oleagineum. Our results highlight a relationship between climatic conditions and the incidence of the disease, consistent with previous studies [34,35]. During the fall–winter period, when the humidity ranges from 80 to 85% and temperatures are between 15 and 25 °C, conditions are optimal for the development of the pathogen, favoring sporulation, conidium germination, and infection, as reported by Obanor [35]. This period, which coincides with the pathogen’s active phase, aligns with findings by Viruega and Trapero [36] and Graniti [37], who noted that the main infection periods occur during the fall and winter months. Moreover, conidium production is most abundant during the cooler, moist spring and autumn months, while it is significantly reduced during the hot summer, when the pathogen remains dormant. These results confirm that the combination of moist weather conditions and moderate temperatures plays a critical role in the disease’s progression. These findings further corroborate the critical role of environmental conditions in influencing the pathogen’s life cycle and infection dynamics.

The spatial and multi-temporal analysis highlights the impact of microtopography and climate on OLS disease progression, underscoring topographic variation as a critical factor. These results demonstrate that disease severity is closely linked to factors such as canopy density, ambient humidity, and altitude, which create distinct gradients of OLS severity within the orchard. The results of this study demonstrate a clear relationship between environmental factors and the severity of olive leaf spot disease. Higher disease incidences and severities were recorded in the central depression near the stream, where elevated humidity levels created favorable conditions for pathogen development, with disease severity exceeding 30%. In contrast, the eastern and western sections of the orchard exhibited significantly lower disease incidence (<10%), likely due to better ventilation and drier conditions. This finding is consistent with previous research indicating that trees growing in sheltered areas, such as near hedges or in hollows, tend to experience higher disease prevalence and severity [30]. Furthermore, cool and moist environmental conditions are known to favor the epidemic development of F. oleaginum in olive-growing regions [34,35]. Other studies, such as that of Rhimini et al. [38], have highlighted the crucial role of topographic variation in disease prevalence. Their findings show that disease intensity decreases from low to high slopes, with the presence of rivers exacerbating disease on the south and east-facing slopes, which are typically drier. This is in line with our results, where disease intensity was more pronounced in lower areas, and the proximity to water sources increased the severity of infection. Additionally, studies by Ouerghi et al. [39] observed that trees exposed to the northern direction exhibited higher incidences of leaf spot disease, while those oriented towards the southern and eastern directions had reduced latent infections.

To monitor diseases and ensure high-quality olive production, Precision Agriculture (PA) has emerged as a crucial strategy, representing an agricultural management approach leveraging technology to optimize crop yields and minimize waste. Its overarching objective is to equip farmers with real-time data and insights about their farms and livestock, facilitating accurate decision-making to maximize crop yields and minimize losses [40]. Within the realm of PA technologies, remote sensing has emerged as a cornerstone, extensively employed over the last two decades for monitoring the health of crops [41]. It is a phenomenon in which the physical conditions of the Earth are observed remotely by calculating the emitted and reflected radiation from some distance. This technology has been instrumental in previous studies, contributing to the monitoring of orchard trees’ crown detection and the extraction of tree canopy characteristics [42]. There are special cameras that are used to capture images for further analysis to find the characteristics of a specific area. Multiple platforms are used to mount these cameras that capture images of the objects [41]. The latter can be airborne-based, satellite-based, and Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV)-based [43]. To assess the health of a crop, many vegetation indices have been developed by combining the remote sensing data and the reflectance of monitored surfaces within different wavebands, mainly visible (Green and Red), near-infrared (NIR), and Red Edge. NDVI, the most common spectral index used in the crop studies, is an important data source for many applications, such as the estimation of vegetation photosynthetic activity [44], detection of vegetation phenology [45,46], and classification of land cover [47]. GNDVI coupled with NDVI were correlated with Chlorophyll and Nitrogen content [48]. Moreover, VIs provide consistent spatial and temporal information on global vegetation conditions. They permit, as has been demonstrated in many studies, the distinction of healthy or unhealthy portions of a cultivated field without any ground radiometric measures [49]. Numerous endeavors have been made to apply geospatial methods in the management of olive orchards, encompassing the early detection of Verticilium wilt [50] and Quick Decline Syndrome caused by Xylella fastidiosa [19,51], control of fruit fly infestations [52], and assessment of water stress in olive trees [53,54].

The results obtained through spectral imaging, conducted using UAVs, revealed varying levels of prediction accuracy across the three flights conducted in May, July, and October. This variability can be attributed to the biological characteristics of the pathogen F. oleaginum. In olive orchards, the pathogen persists in the form of survival structures that can germinate under favorable climatic conditions, producing hyphae that penetrate the epidermis of olive leaves and spread into their tissues. Conidiophores subsequently develop on the surface of the lesions, facilitating the fungal spread to the aerial parts of the plant, disrupting water transport and inducing water stress, which manifests as chlorosis symptoms [55,56]. In the Mediterranean region, the incidence and severity of peacock spot symptoms typically increase in late autumn, decrease significantly in summer, and resurge in autumn [37]. Notably, the highest remote sensing accuracy (81.5%) was recorded in October, highlighting the critical role of precision agriculture in the early detection of disease symptoms and their spatial distribution. This approach aids in curbing disease spread and minimizing yield losses.

In our study, the Red Edge and near-infrared (NIR) spectral bands, which constitute the Red Edge_me vegetation index, played a crucial role in the remote sensing of peacock spot disease, particularly for early detection. These bands showed the highest correlation (0.75) between field-assessed disease severity and VI predictions. The NIR band is highly sensitive to changes in canopy structure and leaf water content [57], while the Red Edge band—a narrow spectral range between red and NIR—is particularly responsive to changes in chlorophyll content, an early indicator of stress and disease. The disruptions caused by F. oleaginum lesions affect the spectral signals captured by these bands [37,55,58]. This spectral sensitivity underscores the potential of remote sensing to detect early disease symptoms that are not visible to the naked eye, making it an invaluable tool for precision agriculture practices. These findings align with the results of Fahrentrapp et al. [59], who observed that foliar infections caused by gray mold on tomato plants could be identified as early as nine hours post-infection (hpi) using the NIR and Red Edge bands.

The integration of multispectral imaging with traditional agronomic approaches has significantly enhanced the accuracy of disease monitoring and prediction. Early detection of disease symptoms and their spatial distribution can aid in containing disease spread, reducing production losses, and potentially limiting the need for large-scale pesticide applications. Traditional field inspections are time-consuming, labor-intensive, and prone to human error, making the early detection of diseases particularly challenging when symptoms are not yet fully visible [60]. Remote sensing (RS) addresses many challenges associated with disease detection and monitoring across various crops [42,61]. In the case of olive trees, research has primarily focused on two major diseases: Verticillium wilt (VW), caused by the soilborne fungus Verticillium dahliae Kleb [61,62,63], and the rapid decline syndrome, caused by the bacterium Xylella fastidiosa Wells subspecies pauca [19,64,65]. Our study demonstrated the potential of integrating field-based agronomic assessments with remote sensing technologies to enhance the monitoring and management of olive leaf spot (OLS) in olive orchards. By enabling early disease detection and supporting precise, data-driven interventions, this approach holds promise for sustainable olive production, facilitating proactive disease management amidst increasingly variable environmental conditions. The refinement of this strategy, incorporating hyperspectral imaging and advanced data integration techniques, could bolster the resilience of olive cropping systems and promote the sustainable management of olive diseases in diverse olive-growing regions.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the innovative integration of agronomic assessments and multispectral imaging as a powerful tool for the surveillance and management of olive leaf spot (OLS) disease in olive orchards. By combining traditional agronomic methods with advanced remote sensing technologies, this approach offers a comprehensive framework for disease monitoring, enabling early detection and more precise, data-driven management decisions. The ability to capture spatial and temporal variations in disease progression provides growers with critical insights for implementing targeted interventions, optimizing resource use, and minimizing yield losses.

Given the increasing challenges posed by OLS in olive cultivation, it is crucial to develop and refine such integrated strategies. The use of multispectral and hyperspectral imaging can significantly enhance disease surveillance, allowing for the early identification of stress symptoms that are not visible to the naked eye. Furthermore, integrating these techniques with other precision agriculture tools, such as variable-rate application systems, will contribute to more sustainable and efficient disease management practices. Future research should focus on improving the resolution and accuracy of remote sensing technologies, exploring the physiological responses of olive trees to disease, and expanding the scope of this approach to other olive diseases. This integrated strategy has the potential to revolutionize the way olive orchards are managed, ensuring their long-term health and productivity in the face of evolving environmental challenges.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/horticulturae11010046/s1, Figure S1: Topographic elevation map of the surveyed plot showing contour lines and elevation gradient (632–647 m); Figure S2: Temporal Variation in Correlation and R2 Values of Spectral Indices with Disease Severity in Olive Orchards.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.H., A.E.B. and S.E.I.E.H.; methodology, K.H., A.E.B., H.H., S.E.I.E.H. and R.R.; software, I.M., H.C. and A.E.B.; validation, K.H., S.E.I.E.H., A.A., A.E.B. and S.L.; formal analysis, H.H., I.M. and H.C.; investigation, K.H., A.E.B. and S.E.I.E.H., resources, S.E.I.E.H.; data curation, K.H. and I.M.; writing—original draft preparation, H.H. and K.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the MCRDV-Project 2020–2022 “Competitive Mechanism for Research, Development, and Extension: Feasibility and Contributions of Precision Agriculture in the Olive Sector: Establishment of a Monitoring and Decision Support System for Precision Olive Growing”. Coordinated by Dr. Salma El Iraqui El Houssaini from INRA Meknes.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the MCRDV project. The authors would like to express their gratitude to SOWIT|Ag Intelligence for providing drone-based multispectral imaging services.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kaniewski, D.; Van Campo, E.; Boiy, T.; Terral, J.-F.; Khadari, B.; Besnard, G. Primary Domestication and Early Uses of the Emblematic Olive Tree: Palaeobotanical, Historical and Molecular Evidence from the Middle East. Biol. Rev. 2012, 87, 885–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbuzano, J. Climate Change Will Reduce Spanish Olive Oil Production. Available online: http://eos.org/articles/climate-change-will-reduce-spanish-olive-oil-production (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Cannon, J. Cradle of Transformation: The Mediterranean and Climate Change. Available online: https://news.mongabay.com/2022/04/cradle-of-transformation-the-mediterranean-and-climate-change/ (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Ouraich, I.; Tyner, W.E. Moroccan Agriculture, Climate Change, and the Moroccan Green Plan: A CGE Analysis. Afr. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2018, 13, 307–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, W.; Guiot, J.; Fader, M.; Garrabou, J.; Gattuso, J.-P.; Iglesias, A.; Lange, M.A.; Lionello, P.; Llasat, M.C.; Paz, S.; et al. Climate Change and Interconnected Risks to Sustainable Development in the Mediterranean. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018, 8, 972–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdou Zayan, S. Impact of Climate Change on Plant Diseases and IPM Strategies. In Plant Diseases—Current Threats and Management Trends; Topolovec-Pintarić, S., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2020; ISBN 978-1-78985-115-1. [Google Scholar]

- Graniti, A.; Faedda, R.; Cacciola, S.O.; Magnano di San Lio, G. Olive Diseases in a Changing Ecosystem. In Olive Diseases and Disorders; Transworld Research Network: Thiruvananthapuram, India, 2011; pp. 403–433. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoni, M.; Mercado-Blanco, J. Confronting Stresses Affecting Olive Cultivation from the Holobiont Perspective. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1261754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhimini, Y.; Bouaichi, A.; Chliyeh, M.; Msairi, S.; Touhami, A.; Benkirane, R.; Achbani, E.; Douira, A. Influence of Variations in Climatic Factors and Some Cultural Practices on Knot Disease Development on Oleaster and Olive Tree (Olea europaea L.) Northwest of Morocco. ARRB 2018, 24, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Lamothe, R.; Segura, R.; Trapero, A.; Baldoni, L.; Botella, M.A.; Valpuesta, V. Phylogeny of the Fungus Spilocaea oleagina, the Causal Agent of Peacock Leaf Spot in Olive. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2002, 210, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Habbadi, K.; Maafa, I.; Benbouazza, A.; Aoujil, F.; Choukri, H.; El Houssaini, S.E.I.; El Bakkali, A. Differential Response of Olive Cultivars to Leaf Spot Disease (Fusicladium oleagineum) under Climate Warming Conditions in Morocco. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renaud, P. Ecologie de la maladie de l’œil de paon et résistance variétale dans leurs incidences sur la culture de l’olivier dans le pays. Afrimed. Al-Awamia 1968, 26, 55–74. [Google Scholar]

- Issa, T.; Almadi, L.; Jarrar, S.; Tucci, M.; Buonaurio, R.; Famiani, F. Factors Affecting Venturia oleaginea Infections on Olive and Effects of the Disease on Floral Biology. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2019, 58, 221–229. [Google Scholar]

- ONSSA: Office National de Sécurité Sanitaire et Alimentaire. Bulletin de Veille Phytosanitaire; 2016. Available online: https://www.onssa.gov.ma/evaluation-des-risques/surveillance-des-risques-phytosanitaires/ (accessed on 28 February 2022).

- John, M.A.; Bankole, I.; Ajayi-Moses, O.; Ijila, T.; Jeje, T.; Lalit, P. Relevance of Advanced Plant Disease Detection Techniques in Disease and Pest Management for Ensuring Food Security and Their Implication: A Review. AJPS 2023, 14, 1260–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonaurio, R.; Almadi, L.; Famiani, F.; Moretti, C.; Agosteo, G.E.; Schena, L. Olive Leaf Spot Caused by Venturia oleaginea: An Updated Review. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1061136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, A.P.; Li, S.; Cao, Z.; Hu, P.J.-H.; Wang, J.; Xiang, Y.; Xie, D.; Lu, X. AI for Science: Predicting Infectious Diseases. J. Saf. Sci. Resil. 2024, 5, 130–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, S.; Pereira, S.; Dinis, L.-T.; Brito, C. Enhancing Olive Cultivation Resilience: Sustainable Long-Term and Short-Term Adaptation Strategies to Alleviate Climate Change Impacts. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castrignanò, A.; Belmonte, A.; Antelmi, I.; Quarto, R.; Quarto, F.; Shaddad, S.; Sion, V.; Muolo, M.R.; Ranieri, N.A.; Gadaleta, G.; et al. Semi-Automatic Method for Early Detection of Xylella fastidiosa in Olive Trees Using UAV Multispectral Imagery and Geostatistical-Discriminant Analysis. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazal, S.; Munir, A.; Qureshi, W.S. Computer Vision in Smart Agriculture and Precision Farming: Techniques and Applications. Artif. Intell. Agric. 2024, 13, 64–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riefolo, C.; Antelmi, I.; Castrignanò, A.; Ruggieri, S.; Galeone, C.; Belmonte, A.; Muolo, M.R.; Ranieri, N.A.; Labarile, R.; Gadaleta, G.; et al. Assessment of the Hyperspectral Data Analysis as a Tool to Diagnose Xylella fastidiosa in the Asymptomatic Leaves of Olive Plants. Plants 2021, 10, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, B.G.; Oduor, P.; Igathinathane, C.; Howatt, K.; Sun, X. A Systematic Review of Hyperspectral Imaging in Precision Agriculture: Analysis of Its Current State and Future Prospects. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 222, 109037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, A.; Zhang, Z.; Zheng, H.; Alami, M.M.; Alrefaei, A.F.; Abbas, Q.; Naqvi, S.A.H.; Rao, M.J.; Mosa, W.F.A.; Abbas, Q.; et al. Drones in Plant Disease Assessment, Efficient Monitoring, and Detection: A Way Forward to Smart Agriculture. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsvetkov, M.Y. Satellite and Drone Multispectral and Thermal Images Data Fusion for Intelligent Agriculture Monitoring and Decision Making Support. In Proceedings of the Remote Sensing for Agriculture, Ecosystems, and Hydrology XXV; Neale, C.M., Maltese, A., Eds.; SPIE: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; p. 65. [Google Scholar]

- Mgendi, G. Unlocking the Potential of Precision Agriculture for Sustainable Farming. Discov. Agric. 2024, 2, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D-Maps: Cartes Gratuites, Cartes Vierges Gratuites, Cartes Muettes Gratuites, Cartes de Base Gratuites. Available online: https://d-maps.com/index.php?lang=en (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Présentation—Google Earth. Available online: https://www.google.com/intl/fr/earth/about/ (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Teviotdale, B.; Sibbett, G.; Harper, D. Several Copper Fungicides Control Olive Leaf Spot. Calif. Agric. 1989, 43, 30–31. [Google Scholar]

- Shabi, E.; Birger, R.; Lavee, S. Leaf Spot (Spilocaea oleaginea) of Olive in Israel and Its Control. Acta Hortic. 1994, 356, 390–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, A.J.; Walter, M.; Trought, M.C.; Frampton, C.M.; Burnip, G. Survey of Olive Leaf Spot in New Zealand. N. Z. Plant Prot. 2000, 53, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachet, M.R.; Danner, M.A.; Citadin, I.; Pertille, R.H.; Guerrezi, M.T. Standard Area Diagram Set for Olive Leaf Spot Assessment. Cienc. Rural 2017, 47, e20160923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Simko, I.; Piepho, H.-P. The Area Under the Disease Progress Stairs: Calculation, Advantage, and Application. Phytopathology 2012, 102, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seem, R.C. Disease Incidence and Severity Relationships. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 1984, 22, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, M.; Hawamda, A.-A.; Amarni, A.A.-A.; Rahil, M.; Hajjeh, H.; Natsheh, B.; Abuamsha, R. Evaluation of the Incidence and Severity of Olive Leaf Spot Caused by Spilocaea oleagina on Olive Trees in Palestine. AJPS 2011, 2, 457–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obanor, F.O. Effect of Temperature, Relative Humidity, Leaf Wetness and Leaf Age on Spilocaea Oleagina Conidium Germination on Olive Leaves. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2008, 120, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viruega, J.R.; Trapero, A. Epidemiology of Leaf Spot of Olive Tree Caused by Spilocaea oleagina in Southern Spain. Acta Hortic. 1999, 474, 531–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graniti, A. Olive Scab: A Review1. EPPO Bull. 1993, 23, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhimini, Y.; Chliyeh, M.; Chahdi, A.; Touati, J.; Ouazzani Touhami, A.; Benkirane, R.; Douira, A. Influence of Certain Cultural Practices and Variable Climatic Factors on the Manifestation of Spilocaea oleagina, Olive Peacock Spot Agent in the Northwestern Region of Morocco. Int. J. Pure Appl. Biosci. 2014, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Ouerghi, F.; Rhouma, A.; Rassaa, N.; Hennachi, I.; Nasraoui, B. Factors Affecting Resistance of Two Olive Cultivars to Leaf Spot Disease in the North West of Tunisia. EJARBLS 2016, 4, 39–51. [Google Scholar]

- El Iraqui El Houssaini, S.; Iaaich, H.; El Bakkali, A.; Razouk, R.; Bouhafa, K.; Habbadi, K.; Benbouazza, A.; Alghoum, M.; Douaik, A. Assessment of the Spatiotemporal Variability of Trees Status in an Olive Orchard through Multispectral Drone Images. Afr. Mediterr. Agric. J. Al Awamia 2021, 132, 142–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafi, U.; Mumtaz, R.; García-Nieto, J.; Hassan, S.A.; Zaidi, S.A.R.; Iqbal, N. Precision Agriculture Techniques and Practices: From Considerations to Applications. Sensors 2019, 19, 3796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messina, G.; Modica, G. Twenty Years of Remote Sensing Applications Targeting Landscape Analysis and Environmental Issues in Olive Growing: A Review. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudd, J.D.; Roberson, G.T.; Classen, J.J. Application of Satellite, Unmanned Aircraft System, and Ground-Based Sensor Data for Precision Agriculture: A Review. In Proceedings of the 2017 Spokane, Washington, DC, USA, 16–19 July 2017; American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers: St. Joseph, MI, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Myneni, R.B.; Hoffman, S.; Knyazikhin, Y.; Privette, J.L.; Glassy, J.; Tian, Y.; Wang, Y.; Song, X.; Zhang, Y.; Smith, G.R.; et al. Global Products of Vegetation Leaf Area and Fraction Absorbed PAR from Year One of MODIS Data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 83, 214–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, R.; Shen, M.; Zhou, J.; Chen, J. Modeling Vegetation Green-up Dates across the Tibetan Plateau by Including Both Seasonal and Daily Temperature and Precipitation. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2018, 249, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Tarpley, D.; Sullivan, J.T. Diverse Responses of Vegetation Phenology to a Warming Climate. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2007, 34, L19405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedl, M.A.; McIver, D.K.; Hodges, J.C.F.; Zhang, X.Y.; Muchoney, D.; Strahler, A.H.; Woodcock, C.E.; Gopal, S.; Schneider, A.; Cooper, A.; et al. Global Land Cover Mapping from MODIS: Algorithms and Early Results. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 83, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, G.E.; Howell, B.M.; Johnson, G.V.; Raun, W.R.; Solie, J.B.; Stone, M.L. Optical Sensing of Turfgrass Chlorophyll Content and Tissue Nitrogen. HortScience 2004, 39, 1130–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candiago, S.; Remondino, F.; De Giglio, M.; Dubbini, M.; Gattelli, M. Evaluating Multispectral Images and Vegetation Indices for Precision Farming Applications from UAV Images. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 4026–4047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón, R.; Navas-Cortés, J.A.; Lucena, C.; Zarco-Tejada, P.J. High-Resolution Airborne Hyperspectral and Thermal Imagery for Early Detection of Verticillium Wilt of Olive Using Fluorescence, Temperature and Narrow-Band Spectral Indices. Remote Sens. Environ. 2013, 139, 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poblete, T.; Camino, C.; Beck, P.S.A.; Hornero, A.; Kattenborn, T.; Saponari, M.; Boscia, D.; Navas-Cortes, J.A.; Zarco-Tejada, P.J. Detection of Xylella fastidiosa Infection Symptoms with Airborne Multispectral and Thermal Imagery: Assessing Bandset Reduction Performance from Hyperspectral Analysis. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2020, 162, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontikakos, C.M.; Tsiligiridis, T.A.; Drougka, M.E. Location-Aware System for Olive Fruit Fly Spray Control. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2010, 70, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battista, P.; Bellini, E.; Chiesi, M.; Costafreda-Aumedes, S.; Fibbi, L.; Leolini, L.; Moriondo, M.; Rapi, B.; Rossi, R.; Sabatini, F.; et al. Estimating the Effect of Water Shortage on Olive Trees by the Combination of Meteorological and Sentinel-2 Data. Eur. J. Remote Sens. 2023, 56, 2194553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepulcre-Cantó, G.; Zarco-Tejada, P.J.; Jiménez-Muñoz, J.C.; Sobrino, J.A.; de Miguel, E.; Villalobos, F.J. Detection of Water Stress in an Olive Orchard with Thermal Remote Sensing Imagery. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2006, 136, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benitez, Y.; Botella, M.A.; Trapero, A.; Alsalimiya, M.; Caballero, J.L.; Dorado, G.; Muñoz-Blanco, J. Molecular Analysis of the Interaction between Olea europaea and the Biotrophic Fungus Spilocaea oleagina. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2005, 6, 425–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahiaoui, R.; Guéchi, A.; Lukasova, E.; Girre, L. Mutagenic and Membranal Effect of Phytotoxic Molecule Isoled from Olive Parasitized by the Fungus Cycloconium oleaginum. J. Mycotoxicoses Mycooxins 1994, 126, 121–129. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, H.G.; Vaughan, R.A. Remote Sensing of Vegetation: Principles, Techniques, and Applications; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010; ISBN 978-0-19-920779-4. [Google Scholar]

- Ayres, P.G. Water Relations of Diseased Plants. Water Plant Dis. 1978, 5, 1–60. [Google Scholar]

- Fahrentrapp, J.; Ria, F.; Geilhausen, M.; Panassiti, B. Detection of Gray Mold Leaf Infections Prior to Visual Symptom Appearance Using a Five-Band Multispectral Sensor. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehsani, R.; Maja, J.M. The Rise of Small UAVs in Precision Agriculture. Resour. Eng. Technol. A Sustain. World 2013, 20, 18–19. [Google Scholar]

- Makhloufi, A.; Abdelmoula, H.; Ben Abdallah, A.; Kallel, A. Olive Tree Health Monitoring Approach Using Satellite Images and Based on Artificial Intelligence: Toward Automatic Olive Stress Detection Solution. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2022—2022 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 17–22 July 2022; pp. 7839–7842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón, R.; Navas-Cortés, J.A.; Zarco-Tejada, P.J. Early Detection and Quantification of Verticillium Wilt in Olive Using Hyperspectral and Thermal Imagery over Large Areas. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 5584–5610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iatrou, G.; Mourelatos, S.; Zartaloudis, Z.; Iatrou, M.; Gewehr, S.; Kalaitzopoulou, S. Remote Sensing for the Management of Verticillium Wilt of Olive. Fresenius Environ. Bull. 2016, 25, 3622–3628. [Google Scholar]

- Di Nisio, A.; Adamo, F.; Acciani, G.; Attivissimo, F. Fast Detection of Olive Trees Affected by Xylella fastidiosa from UAVs Using Multispectral Imaging. Sensors 2020, 20, 4915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornero, A.; Hernández-Clemente, R.; Beck, P.S.A.; Navas-Cortés, J.A.; Zarco-Tejada, P.J. Using Sentinel-2 Imagery to Track Changes Produced by Xylella fastidiosa in Olive Trees. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2018—2018 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Valencia, Spain, 22–27 July 2018; pp. 9060–9062. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).