Extracellular Polymeric Substance Production in Rhodococcus: Advances and Perspectives

Abstract

1. Introduction

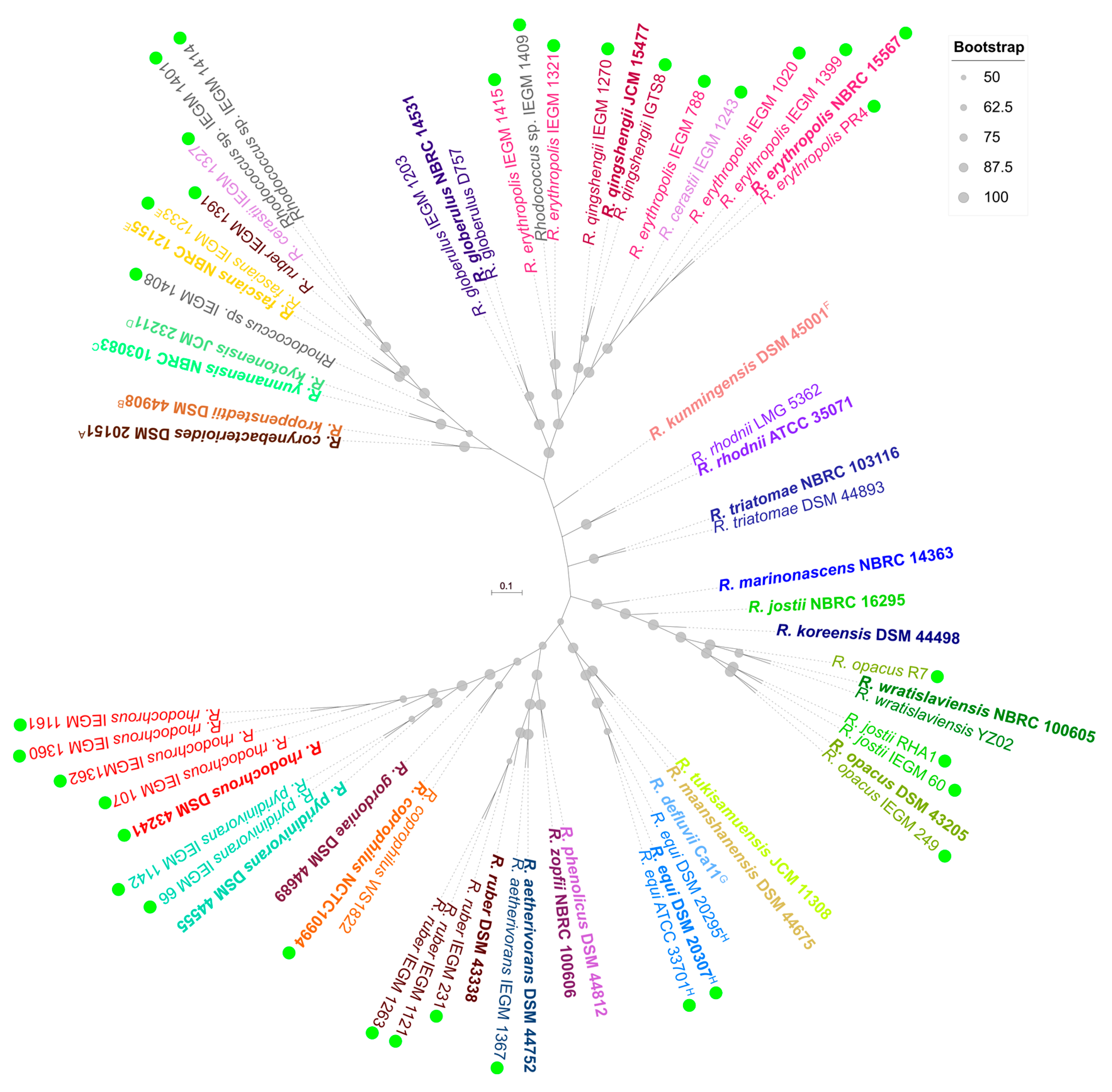

2. Taxonomic Distribution of EPS Producers in Rhodococcus

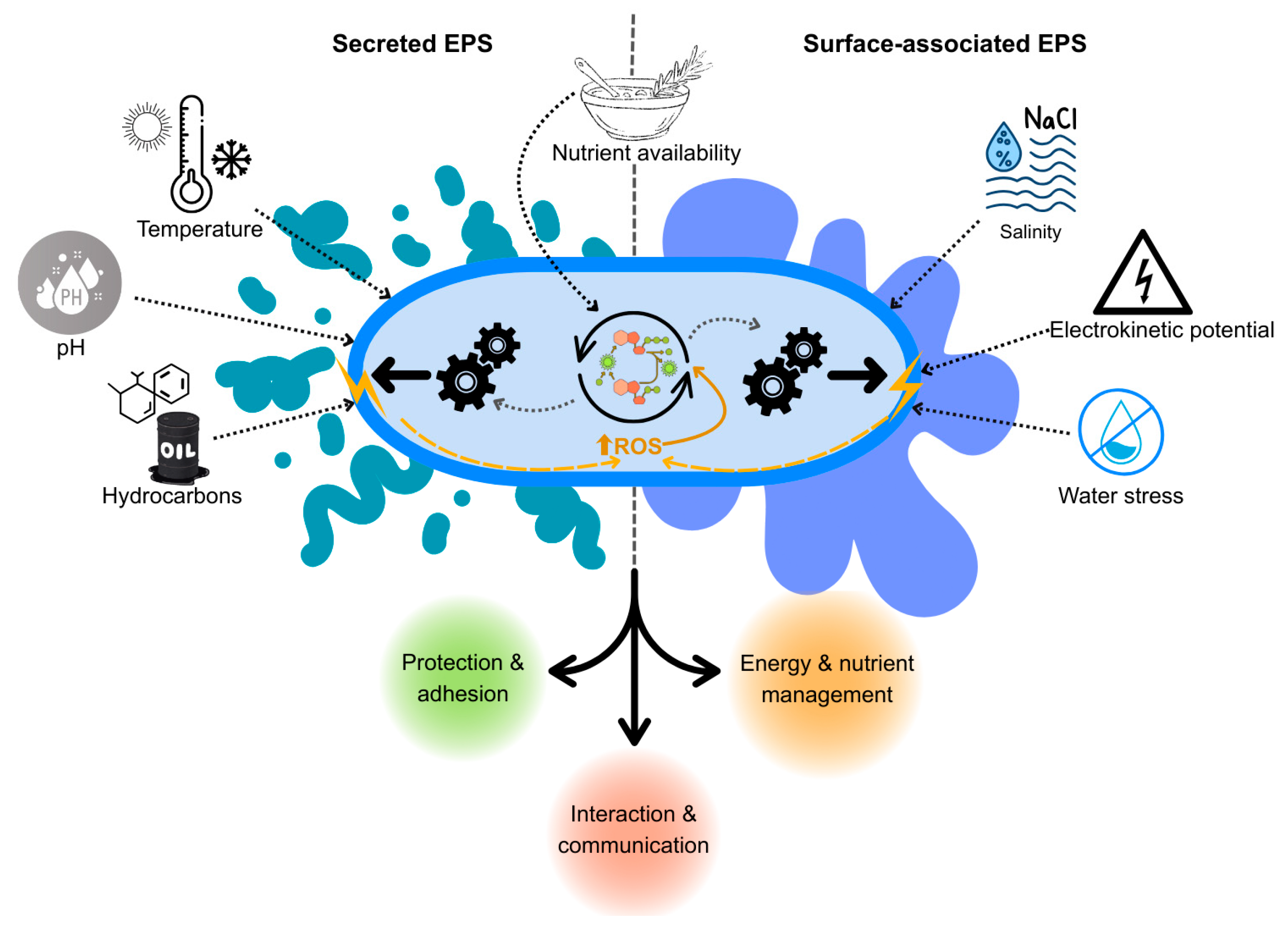

3. Factors Affecting EPS Production

| Environmental Factor | Impact on EPS Production | References |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature | EPS production is sensitive to temperature variations, with optimal ranges promoting higher yields. Deviations may lead to reduced production due to metabolic stress. | [14,16] |

| pH | The acidic or basic nature of the environment can significantly affect EPS biosynthesis. Each Rhodococcus species has specific pH ranges conducive to optimal EPS production. | [9,14] |

| Nutrient availability | The presence of specific nutrients, particularly carbon and nitrogen sources, is essential for stimulating EPS synthesis. Limited nutrients can lead to decreased production levels. | [9,16,17] |

| Salinity | Higher salinity can trigger stress responses that may stimulate EPS production as a protective mechanism. However, extremely high levels can be detrimental. | [9] |

| Hydrocarbon presence | The presence of hydrocarbons serves both as a carbon source and as a stressor, potentially enhancing EPS production for cellular protection against toxicity. | [14,16] |

| Electrokinetic potential | Variations in the electrokinetic properties of cell surfaces, influenced by EPS, can affect their interaction with the environment and overall EPS production capabilities. | [14,16] |

| Water stress | Metabolic slowdown, use of intracellular TAGs for the synthesis of EPS. | [18] |

4. Chemical Composition of EPS in the Rhodococcus Genus

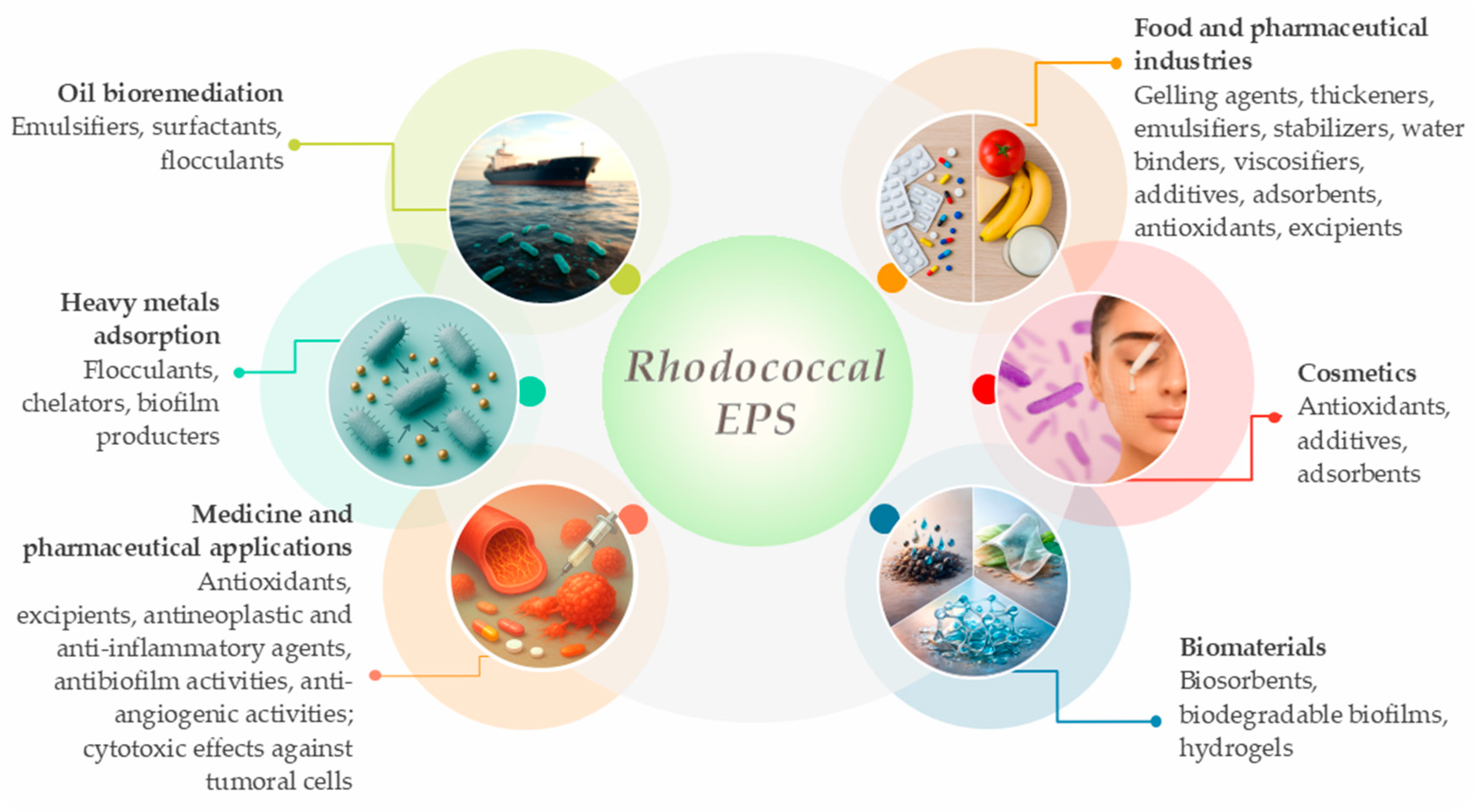

5. Biological Properties, Yields, and Biotechnological Applications

| Strain | Maximum Yields (g/L) | Biological Activities and Related Biotechnological Applications | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| R. erythropolis DSM 43215 | 1.94 | Anti-inflammatory agent | [30] |

| R. erythropolis AU-1 | 5.00 | Emulsifier | [50] |

| R. erythropolis HX-2 | 6.37 (normal conditions) 8.96 (optimized conditions) 3.74 (purified) | Gelling agent, thickener, emulsifier, stabilizer, water binder or viscosifier (food industry) Additive and adsorbent (food, cosmetic, and pharmaceutical industries) Cytotoxicity against tumoral cells, antineoplastic agent (medicine and pharmaceutical industry) | [31] |

| R. erythropolis IEGM 1415 | 0.07 | N.D. | [9] |

| R. erythropolis PR4 | N.D. | Oil emulsifier | [33] |

| R. jostii RHA1 | 0.01 (wt) 0.05 (OE nlpR *) | N.D. | [17] |

| R. opacus 89 UMCS | 0.18 | Flocculant Adsorbent of heavy metals Modulator of calcium carbonate mineralisation | [35,51] |

| R. pyridinivorans ZZ47 | 17.12 (wet EPS) 10.14 (dry EPS) | Antibiofilm and antiangiogenic activity Cytotoxicity against tumoral cells Antioxidant activity | [52,53] |

| R. qingshengii IGTS8 | 1.70 g/100 g cell | Thickener | [37] |

| R. qingshengii LMR356 | 1.95 3.64 (+30 mM Pb) | Lead tolerance (heavy-metal bioremediation) | [54] |

| R. qingshengii QDR4-2 | 3.85 | Emulsifier and antioxidant (health, food, and pharmaceutical industries) | [38] |

| R. rhodochrous | 0.27 | Flocculant | [39] |

| R. rhodochrous S-2 | N.D. | Emulsifier, thickener, moisture-absorber, and moisture-retentor | [55] |

| R. rhodococcus sp. MI 2 | 7.4 | Biosorbent for Fe(III) and Cu(II) | [46,56] |

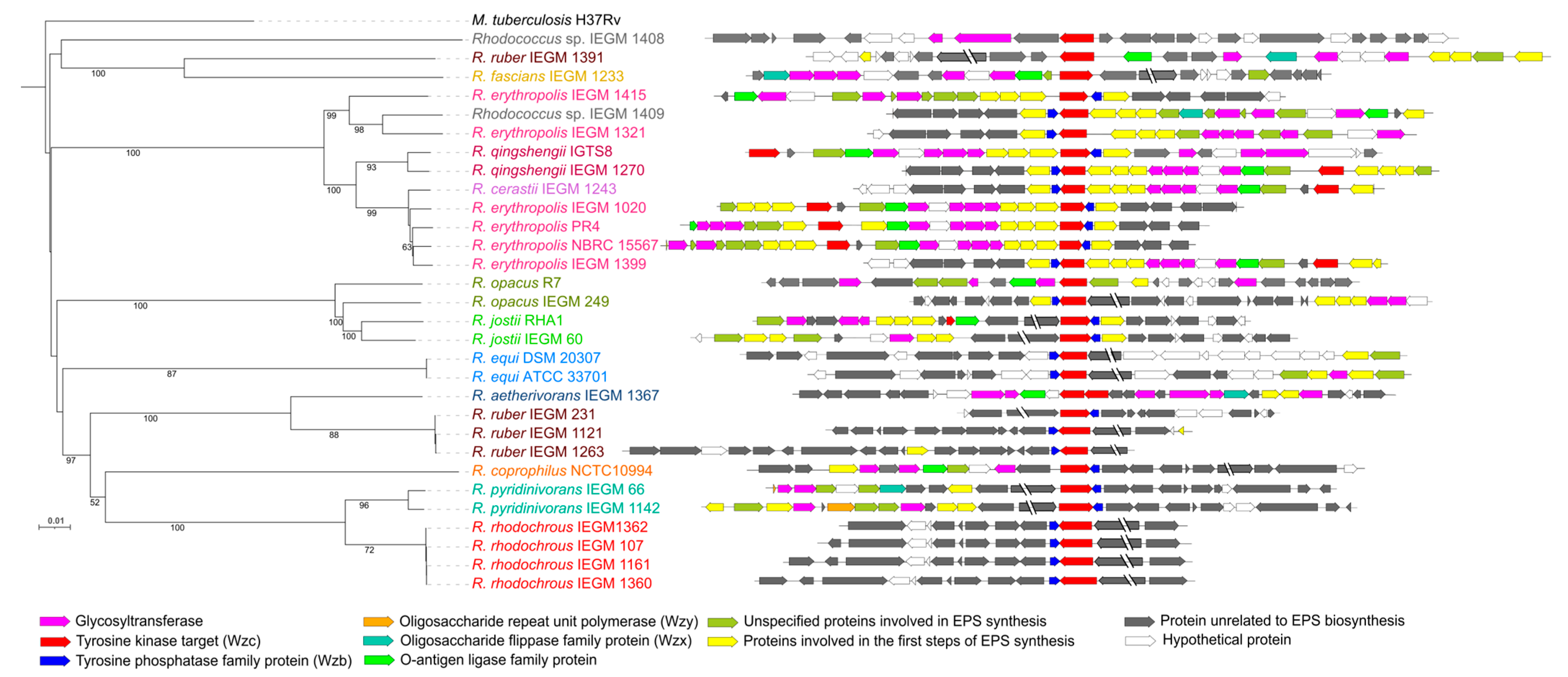

6. Genes Relevant to EPS Biosynthesis

7. Conclusions and Future Research Perspectives

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alvarez, H.M.; Hernández, M.A.; Lanfranconi, M.P.; Silva, R.A.; Villalba, M.S. Rhodococcus as biofactories for microbial oil production. Molecules 2021, 26, 4871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappelletti, M.; Presentato, A.; Piacenza, E.; Firrincieli, A.; Turner, R.J.; Zannoni, D. Biotechnology of Rhodococcus for the production of valuable compounds. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 104, 8567–8594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyaya, C.; Patel, H.; Patel, I.; Upadhyaya, T. Extremophilic exopolysaccharides: Bioprocess and novel applications in 21 st century. Fermentation 2025, 11, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.T.; Pham, T.T.; Nguyen, P.T.; Le-Buanec, H.; Rabetafika, H.N.; Razafindralambo, H.L. Advances in microbial exopolysaccharides: Present and future applications. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Netrusov, A.I.; Liyaskina, E.V.; Kurgaeva, I.V.; Liyaskina, A.U.; Yang, G.; Revin, V.V. Exopolysaccharides producing bacteria: A review. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nouioui, I.; Carro, L.; García-López, M.; Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Woyke, T.; Kyrpides, N.C.; Pukall, R.; Klenk, H.P.; Goodfellow, M.; Göker, M. Genome-based taxonomic classification of the phylum Actinobacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Val-Calvo, J.; Vázquez-Boland, J.A. Mycobacteriales taxonomy using network analysis-aided, context-uniform phylogenomic approach for non-subjective genus demarcation. mBio 2023, 14, e0220723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappelletti, M.; Zampolli, J.; Di Gennaro, P.; Zannoni, D. Genomics of Rhodococcus. In Biology of Rhodococcus. Microbiology Monographs, 2nd ed.; Alvarez, H., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 16, pp. 23–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krivoruchko, A.; Nurieva, D.; Luppov, V.; Kuyukina, M.; Ivshina, I. The lipid- and polysaccharide-rich extracellular polymeric substances of Rhodococcus support biofilm formation and protection from toxic hydrocarbons. Polymers 2025, 17, 1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangal, V.; Goodfellow, M.; Jones, A.L.; Seviour, R.J.; Sutcliffe, I.C. Refined systematics of the genus Rhodococcus based on whole genome analyses. In Biology of Rhodococcus. Microbiology Monographs, 2nd ed.; Alvarez, H., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 16, pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Göker, M. TYGS is an automated high-throughput platform for state-of-the-art genome-based taxonomy. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangal, V.; Goodfellow, M.; Jones, A.L.; Sutcliffe, I.C. A stable home for an equine pathogen: Valid publication of the binomial Prescottella equi gen. nov., comb. nov., and reclassification of four rhodococcal species into the genus Prescottella. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2022, 72, 005551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomás-Gallardo, L.; Santero, E.; Floriano, B. Involvement of a putative cyclic amp receptor protein (DRP)-like binding sequence and a CRP-like protein in glucose-mediated catabolite repression of thn genes in Rhodococcus sp. strain TFB. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 5460–5462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wei, Q.; Wang, X.; Wu, Y.; Fu, C.; Wang, X.; Hangzhou, X.; Li, L. Characterizing the contaminant-adhesion of a dibenzofuran degrader Rhodococcus sp. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, N.; Hayasaki, T.; Takagi, H. Gene expression analysis of methylotrophic oxidoreductases involved in the oligotrophic growth of Rhodococcus erythropolis N9T-4. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2011, 75, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivshina, I.B.; Krivoruchko, A.V.; Kuyukina, M.S.; Peshkur, T.A.; Cunningham, C.J. Adhesion of Rhodococcus bacteria to solid hydrocarbons and enhanced biodegradation of these compounds. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 21559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, M.A.; Gleixner, G.; Sachse, D.; Alvarez, H.M. Carbon allocation in Rhodococcus jostii RHA1 in response to disruption and overexpression of nlpR regulatory gene, based on 13C-labeling analysis. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez, H.M.; Silva, R.A.; Cesari, A.C.; Zamit, A.L.; Peressutti, S.R.; Reichelt, R.; Keller, U.; Malkus, U.; Rasch, C.; Maskow, T.; et al. Physiological and morphological responses of the soil bacterium Rhodococcus opacus strain PD630 to water stress. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2004, 50, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sazykin, I.; Makarenko, M.; Khmelevtsova, L.; Seliverstova, E.Y.; Rakin, A.; Sazykina, M. Cyclohexane, naphthalene, and diesel fuel increase oxidative stress, CYP153, sodA, and recA gene expression in Rhodococcus erythropolis. Microbiologyopen 2019, 8, e00855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juárez, K.; Reza, L.A.A.; Bretón-Deval, L.; Morales-Guzmán, D.; Trejo-Hernández, M.R.; García-Guevara, F.; Lara, P. Microaerobic degradation of crude oil and long chain alkanes by a new Rhodococcus strain from Gulf of Mexico. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 39, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, L.T.; Irina, P.; Natalia, S.; Irina, N.; Lenar, A.; Andrey, F.; Ekaterina, A.; Sergey, A.; Olga, P. Hydrocarbons biodegradation by Rhodococcus: Assimilation of hexadecane in different aggregate states. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajna, K.V.; Sharma, S.; Nadda, A.K. Microbial exopolysaccharides: An introduction. In Microbial Exopolysaccharides as Novel and Significant Biomaterials, 1st ed.; Nadda, A.K., Sajna, K.V., Sharma, S., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelin, J.; Kavitha, M. Exopolysaccharides from probiotic bacteria and their health potential. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 162, 853–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severn, W.B.; Richards, J.C. The acidic specific capsular polysaccharide of Rhodococcus equi serotype 3. Structural elucidation and stereochemical analysis of the lactate ether and pyruvate acetal substituents. Can. J. Chem. 1992, 70, 2664–2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severn, W.B.; Richards, J.C. The structure of the specific capsular polysaccharide of Rhodococcus equi serotype 4. Carbohydr. Res. 1999, 320, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miertus, S.; Navarini, L.; Cesàro, A. Configurational stability and molecular dynamics of acetal-linked pyruvate substituents in polysaccharides. Carbohydr. Res. 1994, 257, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitch, R.A.; Richards, J.C. Structural analysis of the specific capsular polysaccharide of Rhodococcus equi serotype 1. Biochem. Cell Biol. 1990, 68, 778–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severn, W.B.; Richards, J.C. Structural analysis of the specific capsular polysaccharide of Rhodococcus equi serotype 2. Carbohydr. Res. 1990, 206, 311–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoud, H.; Richards, J.C. Structural elucidation of the specific capsular polysaccharide of Rhodococcus equi serotype 7. Carbohydr. Res. 1994, 252, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapp, P.; Beck, C.H.; Wagner, F. Formation of exopolysaccharides by Rhodococcus erythropolis and partial characterization of a heteropolysaccharide of high molecular weight. Eur. J. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1979, 7, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Li, D.; Qiao, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, W.; Huang, L. Purification, characterization and anticancer activities of exopolysaccharide produced by Rhodococcus erythropolis HX-2. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 145, 646–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urai, M.; Yoshizaki, H.; Anzai, H.; Ogihara, J.; Iwabuchi, N.; Harayama, S.; Sunairi, M.; Nakajima, M. Structural analysis of mucoidan, an acidic extracellular polysaccharide produced by a pristane-assimilating marine bacterium, Rhodococcus erythropolis PR4. Carbohydr. Res. 2007, 342, 927–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urai, M.; Yoshizaki, H.; Anzai, H.; Ogihara, J.; Iwabuchi, N.; Harayama, S.; Sunairi, M.; Nakajima, M. Structural analysis of an acidic, fatty acid ester-bonded extracellular polysaccharide produced by a pristane-assimilating marine bacterium, Rhodococcus erythropolis PR4. Carbohydr. Res. 2007, 342, 933–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, M.B.; MacLean, L.L.; Patrauchan, M.A.; Vinogradov, E. The structure of the exocellular polysaccharide produced by Rhodococcus sp. RHA1. Carbohydr. Res. 2007, 342, 2223–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czemierska, M.; Szcześ, A.; Pawlik, A.; Wiater, A.; Jarosz-Wilkołazka, A. Production and characterisation of exopolymer from Rhodococcus opacus. Biochem. Eng. J. 2016, 112, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czemierska, M.; Szcześ, A.; Jarosz-Wilkołazka, A. Physicochemical factors affecting flocculating properties of the proteoglycan isolated from Rhodococcus opacus. Biophys. Chem. 2021, 277, 106656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urai, M.; Anzai, H.; Iwabuchi, N.; Sunairi, M.; Nakajima, M. A novel viscous extracellular polysaccharide containing fatty acids from Rhodococcus rhodochrous ATCC 53968. Actinomycetologica 2004, 18, 15–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Hu, X.; Li, J.; Sun, X.; Luo, C.; Zhang, X.; Li, H.; Lu, J.; Li, Y.; Bao, M. Purification, structural characterization, antioxidant and emulsifying capabilities of exopolysaccharide produced by Rhodococcus qingshengii QDR4-2. J. Polym. Environ. 2023, 31, 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czemierska, M.; Szcześ, A.; Hołysz, L.; Wiater, A.; Jarosz-Wilkołazka, A. Characterisation of exopolymer R-202 isolated from Rhodococcus rhodochrous and its flocculating properties. Eur. Polym. J. 2017, 88, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urai, M.; Anzai, H.; Ogihara, J.; Iwabuchi, N.; Harayama, S.; Sunairi, M.; Nakajima, M. Structural analysis of an extracellular polysaccharide produced by Rhodococcus rhodochrous strain S-2. Carbohydr. Res. 2006, 341, 766–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urai, M.; Anzai, H.; Iwabuchi, N.; Sunairi, M.; Nakajima, M. A novel moisture-absorbing extracellular polysaccharide from Rhodococcus rhodochrous SM-1. Actinomycetologica 2002, 16, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neu, T.R.; Poralla, K. An amphiphilic polysaccharide from an adhesive Rhodococcus strain. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1988, 49, 389–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizawa, T.; Neilan, B.A.; Couperwhite, I.; Urai, M.; Anzai, H.; Iwabuchi, N.; Nakajima, M.; Sunairi, M. Relationship between extracellular polysaccharide and benzene tolerance of Rhodococcus sp. 33. Actinomycetologica 2005, 19, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urai, M.; Aizawa, T.; Anzai, H.; Ogihara, J.; Iwabuchi, N.; Neilan, B.; Couperwhite, I.; Nakajima, M.; Sunairi, M. Structural analysis of an extracellular polysaccharide produced by a benzene tolerant bacterium, Rhodococcus sp. 33. Carbohydr. Res. 2006, 341, 616–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinogradov, E.V.; Knirel, Y.A.; Shashkov, A.S.; Gorin, S.E.; Vustina, T.F.; Soiiyfer, V.S.; Esipov, S.E.; Lysak, L.V.; Kochetkov, N.K. Structure of the extracellular polysaccharide from Rhodococcus sp. containing D-lyxo-hexulosonic acid. Bioorg. Khimiya 1988, 14, 1214–1223. [Google Scholar]

- Tanskul, S.; Amornthatree, K.; Jaturonlak, N. A new cellulose-producing bacterium, Rhodococcus sp. MI 2: Screening and optimization of culture conditions. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 92, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flemming, H.C.; Neu, T.R.; Wozniak, D.J. The EPS matrix: The “House of biofilm cells”. J. Bacteriol. 2007, 189, 7945–7947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, N.; Dey, P. Bacterial exopolysaccharides as emerging bioactive macromolecules: From fundamentals to applications. Res. Microbiol. 2023, 174, 104024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiso-Bellón, C.; Randazzo, W.; Carmona-Vicente, N.; Peña-Gil, N.; Cárcamo-Calvo, R.; Lopez-Navarro, S.; Navarro-Lleó, N.; Yebra, M.J.; Monedero, V.; Buesa, J.; et al. Rhodococcus spp. interacts with human norovirus in clinical samples and impairs its replication on human intestinal enteroids. Gut Microbes 2025, 17, 2469716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semeniuk, I.; Koretska, N.; Kochubei, V.; Lysyak, V.; Pokynbroda, T.; Karpenko, E.; Midyana, H. Biosynthesis and characteristics of metabolites of Rhodococcus erythropolis AU-1 strain. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. Food Sci. 2022, 11, e4714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrowolski, R.; Szcześ, A.; Czemierska, M.; Jarosz-Wikołazka, A. Studies of cadmium (II), lead (II), nickel (II), cobalt (II) and chromium (VI) sorption on extracellular polymeric substances produced by Rhodococcus opacus and Rhodococcus rhodochrous. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 225, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güvensen, N.C.; Alper, M.; Taşkaya, A. The evaluation of biological activities of exopolysaccharide from Rhodococcus pyridinovorans in vitro. Eur. J. Res. Dev. 2022, 2, 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taşkaya, A.; Güvensen, N.C.; Güler, C.; Şancı, E.; Karabay Yavaşoğlu, N.Ü. Exopolysaccharide from Rhodococcus pyridinivorans ZZ47 strain: Evaluation of biological activity and toxicity. J. Agric. Prod. 2023, 4, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oubohssaine, M.; Sbabou, L.; Aurag, J. Potential of the plant growth-promoting rhizobacterium Rhodococcus qingshengii LMR356 in mitigating lead stress impact on Sulla spinosissima L. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 46002–46022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urai, M.; Aizawa, T.; Nakajima, M.; Sunairi, M. An anionic polymer incorporating low amounts of hydrophobic residues is a multifunctional surfactant. Part 1: Emulsifying, thickening, moisture-absorption and moisture-retention abilities of a fatty acid-containing anionic polysaccharide. Adv. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2015, 5, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yingkong, P.; Tanskul, S. Adsorption of iron (III) and copper (II) by bacterial cellulose from Rhodococcus sp. MI 2. J. Polym. Environ. 2019, 27, 1948–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouro, C.; Gomes, A.P.; Gouveia, I.C. Microbial exopolysaccharides: Structure, diversity, applications, and future frontiers in sustainable functional materials. Polysaccharides 2024, 5, 241–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, O.; Liu, A.; Lu, C.; Zheng, D.Q.; Qian, C.D.; Wang, P.M.; Jiang, X.H.; Wu, X.C. Increasing viscosity and yields of bacterial exopolysaccharides by repeatedly exposing strains to ampicillin. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 110, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamat, S. Molecular Basis and Genetic Regulation of EPS. In Microbial Exopolysaccharides as Novel and Significant Biomaterials, 1st ed.; Nadda, A.K., Sajna, K.V., Sharma, S., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 45–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laczi, K.; Kis, Á.; Horváth, B.; Maróti, G.; Hegedüs, B.; Perei, K.; Rákhely, G. Metabolic responses of Rhodococcus erythropolis PR4 grown on diesel oil and various hydrocarbons. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99, 9745–9759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, S.; Upadhyay, L.S. Microbial exopolysaccharides: Synthesis pathways, types and their commercial applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 157, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iino, T.; Wang, Y.; Miyauchi, K.; Kasai, D.; Masai, E.; Fujii, T.; Ogawa, N.; Fukuda, M. Specific gene responses of Rhodococcus jostii RHA1 during growth in soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 78, 6954–6962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cereijo, A.E.; Ferretti, M.V.; Iglesias, A.A.; Álvarez, H.M.; Asencion Diez, M.D. Study of two glycosyltransferases related to polysaccharide biosynthesis in Rhodococcus jostii RHA1. Biol. Chem. 2024, 405, 325–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Zhang, X.; Qi, X.; Duan, S.; Feng, Z.; Gong, P.; Wu, Z.; Li, B.; Liu, F. Molecular mechanisms for exopolysaccharides synthesis in Lactobacillus helveticus: Relationship between structural characteristics and genomics. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 368, 124170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bundalovic-Torma, C.; Whitfield, G.B.; Marmont, L.S.; Howell, P.L.; Parkinson, J. A systematic pipeline for classifying bacterial operons reveals the evolutionary landscape of biofilm machineries. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2020, 16, e1007721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simunović, V. Genomic and molecular evidence reveals novel pathways associated with cell surface polysaccharides in bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2021, 97, fiab119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivshina, I.; Bazhutin, G.; Tyumina, E. Rhodococcus strains as a good biotool for neutralizing pharmaceutical pollutants and obtaining therapeutically valuable products: Through the past into the future. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 967127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elias, P.M.; das Neves Vasconcellos Brandão, I.Y.; Maass, D. Unlocking hidden value: The metallurgical promise of Rhodococcus spp. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2025, 24, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simunović, V.; Grubišić, I. Amino acid (acyl carrier protein) ligase-associated biosynthetic gene clusters reveal unexplored biosynthetic potential. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2023, 298, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Liu, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Jiang, S.; Chen, C. Fermentation and kinetics characteristics of a bioflocculant from potato starch wastewater and its application. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 3631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, O.M.; Alvarez, H.M. Fruit residues as substrates for single-cell oil production by Rhodococcus species: Physiology and genomics of carbohydrate catabolism. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 40, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Yu, W.; Zhou, B.; Qiu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Du, R. Analysis of the metabolic process of sugarcane juice fermented by Leuconostoc mesenteroides and identification of exopolysaccharides. Food Res. Int. 2025, 220, 117098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Strain | Substrate | EPS Acronym and Composition | Molecular Weight (kDa) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R. equi serotype 1 (ATCC 33701) | NM plus glucose | A-HeP Mannose/pyruvic acid/glucose/glucuronic acid (1:1:1:2). An acetyl group is attached to glucuronic acid. The pyruvic acid is linked to mannose via an acetal bond. | N.D. | [27] |

| R. equi serotype 2 (ATCC 33702) | N.D. | A-HeP Glucose/mannose/rhamnose/glucuronic acid (1:1:1:1). A carboxyethyl moiety is linked to rhamnose, and two acetyl groups are attached to mannose. | N.D. | [28] |

| R. equi serotype 3 (ATCC 33703) | N.D. | A-HeP Glucose/mannose/glucuronic acid/pyruvic acid/galactose (1:1:1:1:1). A carboxyethyl moiety is linked to mannose. Pyruvic acid is linked to glucuronic acid via an acetal bond. | N.D. | [24] |

| R. equi serotype 4 (ATCC 33704) | N.D. | A-HeP Glucose/mannose/rhodaminic acid/pyruvic acid (2:1:1:1). Pyruvic acid is linked to rhodaminic acid via an acetal bond. | N.D. | [25] |

| R. equi serotype 7 (ATCC 33706) | N.D. | A-HeP Galactose/mannose/rhamnose (1:1:1). A pyruvic acid moiety linked to mannose via an acetal bond. | N.D. | [29] |

| R. erythropolis (DSM 43215) | NM plus glycerol | HeP Sugars (96.6%) and proteins (3.3%). Glucose/mannose (1:1) and traces of glucosamine. | 1140 | [30] |

| R. erythropolis HX-2 | N.D. | A-LHeP Carbohydrates (79.24% w/w), proteins (5.20% w/w) and lipids (8.45% w/w). Glucose (27.29%), mannose (26.66%), galactose (24.83%), fucose (4.79%) and glucuronic acid (15.84%). | 1040 | [31] |

| R. erythropolis PR4 (NBRC 100887) | NM plus salts and glucose | A-HeP Glucose/N-acetylglucosamine/fucose/glucuronic acid (2:1:1:1). | N.D. | [32] |

| NM plus salts and glucose | A-LHeP Galactose/glucose/mannose/glucuronic acid/pyruvic acid (1:1:1:1:1). Pyruvic acid is linked to mannose via an acetal bond. Stearic acid (2.9% w/w) and palmitic acid (4.3% w/w) are attached to the polymer, probably by ester bonds. | N.D. | [33] | |

| R. jostii RHA1 (NBRC 108803) | NM plus glucose | A-HeP Glucose/galactose/fucose/glucuronic acid (1:1:1:1). An acetyl group linked to galactose. | N.D. | [34] |

| R. opacus 89 UMCS (FCL89) | NM plus glucose | A-HeP Polysaccharides (64.6%) and proteins (9.44%). Reducing sugars (184.79 μg/mg), N-acetylated amino sugars (4.17 μg/mg), uronic acids (117.6 μg/mg), amino sugars (9.23 μg/mg), and proteins (142.4 μg/mg). Mannose/galactose/glucose (2.7:1.3:1). | 760 | [35,36] |

| R. qingshengii IGTS8 (ATCC 53968; formerly R. rhodochrous IGTS8) | NM plus salts and glucose | A-LHeP Galactose/glucose/fucose/glucuronic acid (3:2:2:2). In addition, there are pyruvic acid (5.8% w/w) (probably attached via an acetal bond), stearic acid (1.3% w/w), and palmitic acid (4.1% w/w). | >2000 | [37] |

| R. qingshengii QDR4-2 | NM plus salts and glucose | HeP Carbohydrates (92.55% w/w). Mannose/glucose (81.5:18.5). | 945 | [38] |

| R. rhodochrous | MM plus glucose | A-HeP Polysaccharide (62.86%) and protein (10.36%). Reducing sugars (232.41 μg/mg), amino sugars (15.07 μg/mg), and N-acetylated amino sugars (4.84 μg/mg), uronic acids (45.29 μg/mg). Mannose/glucose/galactose (12:6:1). | 1300 | [39] |

| R. rhodochrous S-2 | NM plus salts and glucose | A-LHeP Galactose/mannose/glucose/glucuronic acid (1:1:1:1). Stearic acid (0.8% w/w) and palmitic acid (2.7% w/w). | >2000 | [40] |

| R. rhodochrous SM-1 a | NM plus salts and glucose | A-LHeP Galactose/glucose/fucose/glucuronic acid (6:3:2:4). In addition, there are pyruvic acid (10.3% w/w) (probably attached via an acetal bond), stearic acid (1.2% w/w), and palmitic acid (2.3% w/w). | >2000 | [41] |

| Rhodococcus sp. 33 b | NM plus salts, glucose, and n-hexadecane | A-HeP Glucose/galactose/rhamnose/glucuronic acid (1:1:2:1). One acetate residue per repeating unit. | N.D. | [42] |

| Rhodococcus sp. 33 c | NM plus salts and glucose, MM plus mannitol | A-HeP Neutral sugars (66% w/w), uronic acids (18.4% w/w), and pyruvic acid (15.6% w/w). Galactose/glucose/mannose/glucuronic acid/pyruvic acid (1:1:1:1:1). Pyruvic acid is linked to mannose via an acetal bond. | >2000 | [43,44] |

| Rhodococcus sp. C13-6 | NM plus salts, glucose, and glycerol | A-HeP Glucose/fucose/lyxo-hexulosonic acid (1:2:2) | 250 | [45] |

| Rhodococcus sp. MI 2 | NM plus sucrose or coconut juice medium | HoP Glucose | N.D. | [46] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lanfranconi, M.P.; Silva, R.A.; Sandoval, N.E.; Dávila Costa, J.S.; Alvarez, H.M. Extracellular Polymeric Substance Production in Rhodococcus: Advances and Perspectives. Fermentation 2026, 12, 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation12020082

Lanfranconi MP, Silva RA, Sandoval NE, Dávila Costa JS, Alvarez HM. Extracellular Polymeric Substance Production in Rhodococcus: Advances and Perspectives. Fermentation. 2026; 12(2):82. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation12020082

Chicago/Turabian StyleLanfranconi, Mariana P., Roxana A. Silva, Natalia E. Sandoval, José Sebastián Dávila Costa, and Héctor M. Alvarez. 2026. "Extracellular Polymeric Substance Production in Rhodococcus: Advances and Perspectives" Fermentation 12, no. 2: 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation12020082

APA StyleLanfranconi, M. P., Silva, R. A., Sandoval, N. E., Dávila Costa, J. S., & Alvarez, H. M. (2026). Extracellular Polymeric Substance Production in Rhodococcus: Advances and Perspectives. Fermentation, 12(2), 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation12020082