Palladium Recovery from e-Waste Using Enterobacter oligotrophicus CCA6T

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

2.2. Palladium Recovery Test

2.3. Palladium Extraction from e-Wastes

2.4. Quantification of Palladium

2.5. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

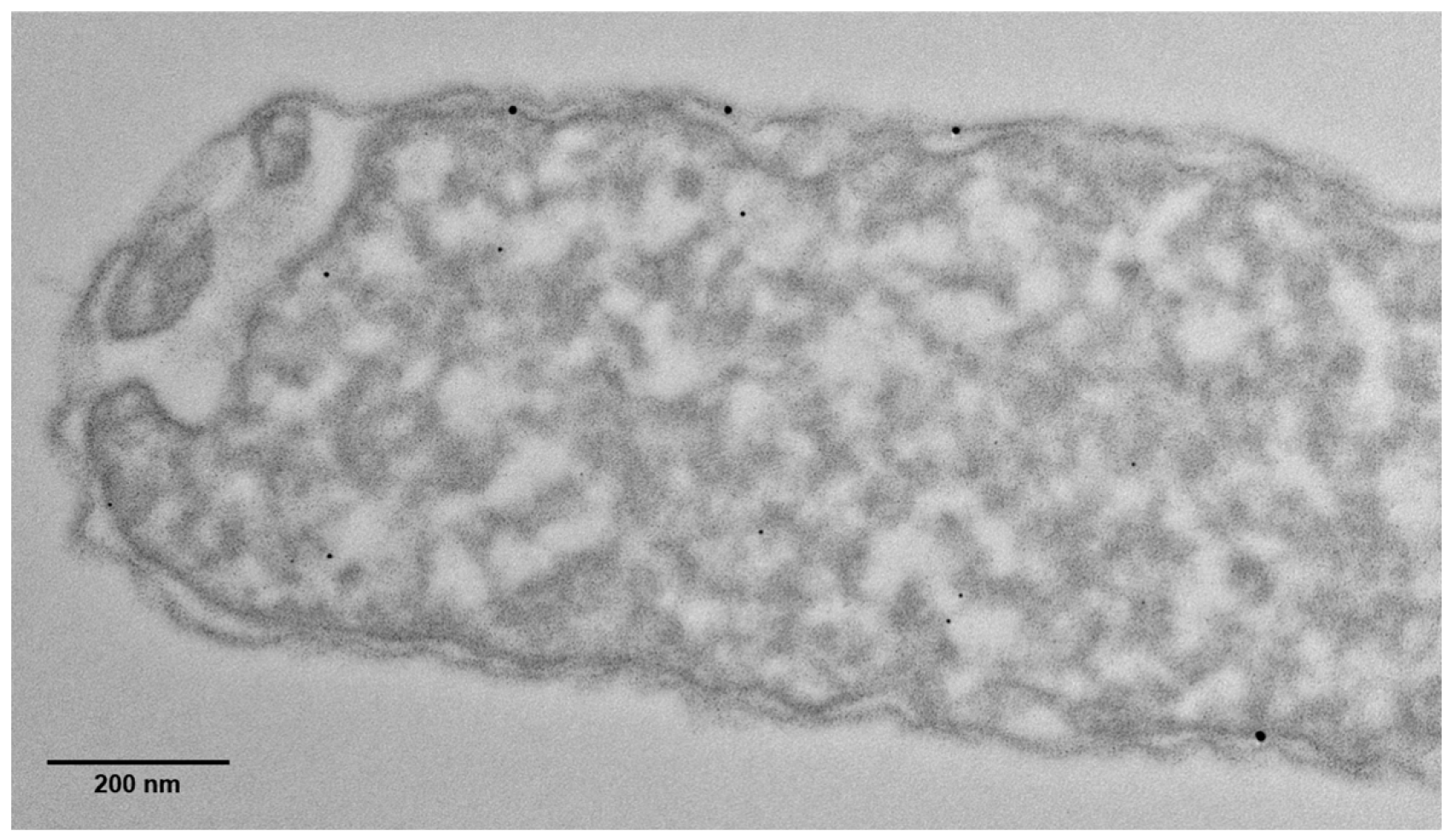

3.1. Confirmation of Palladium Biomineralization

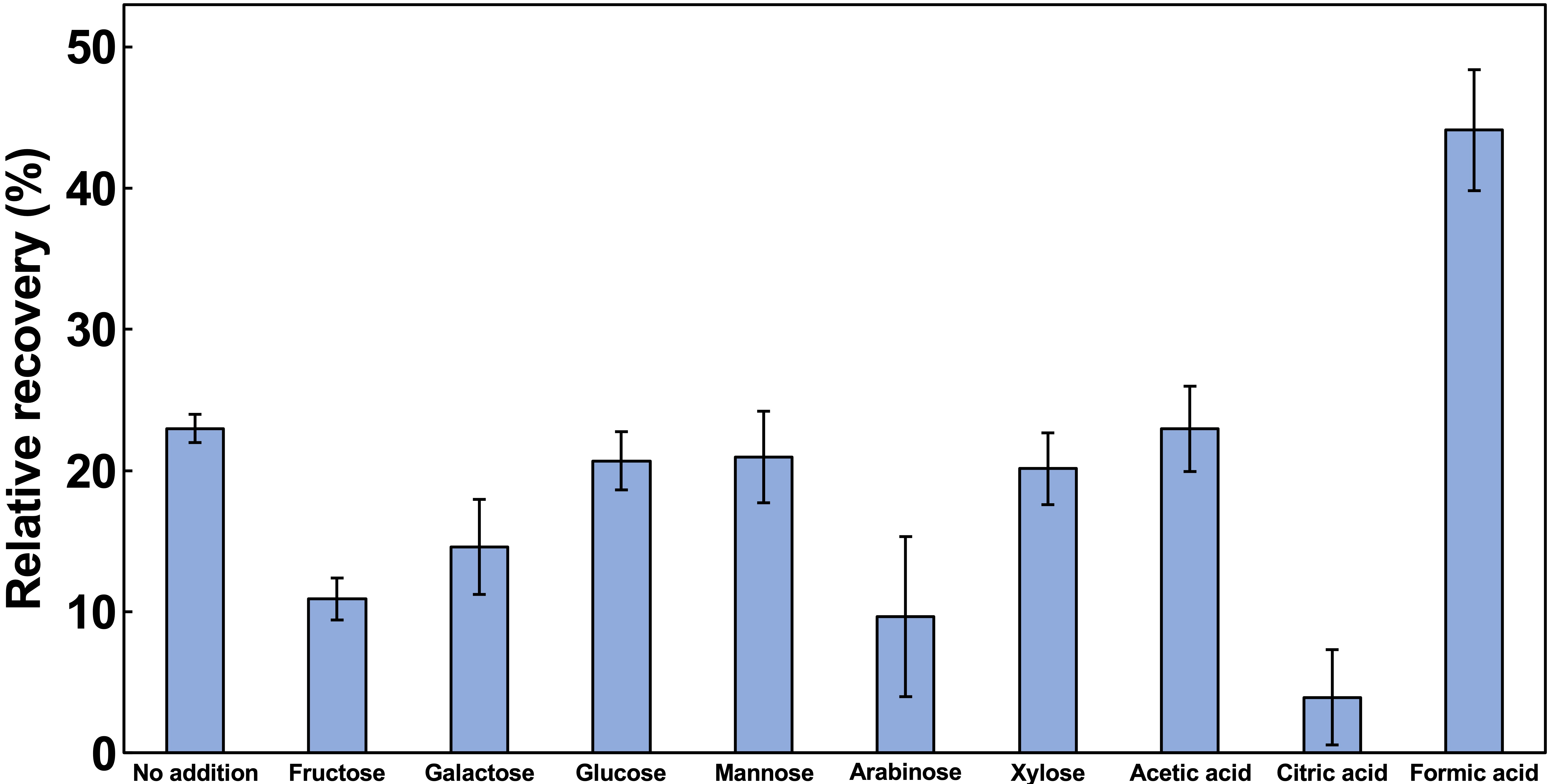

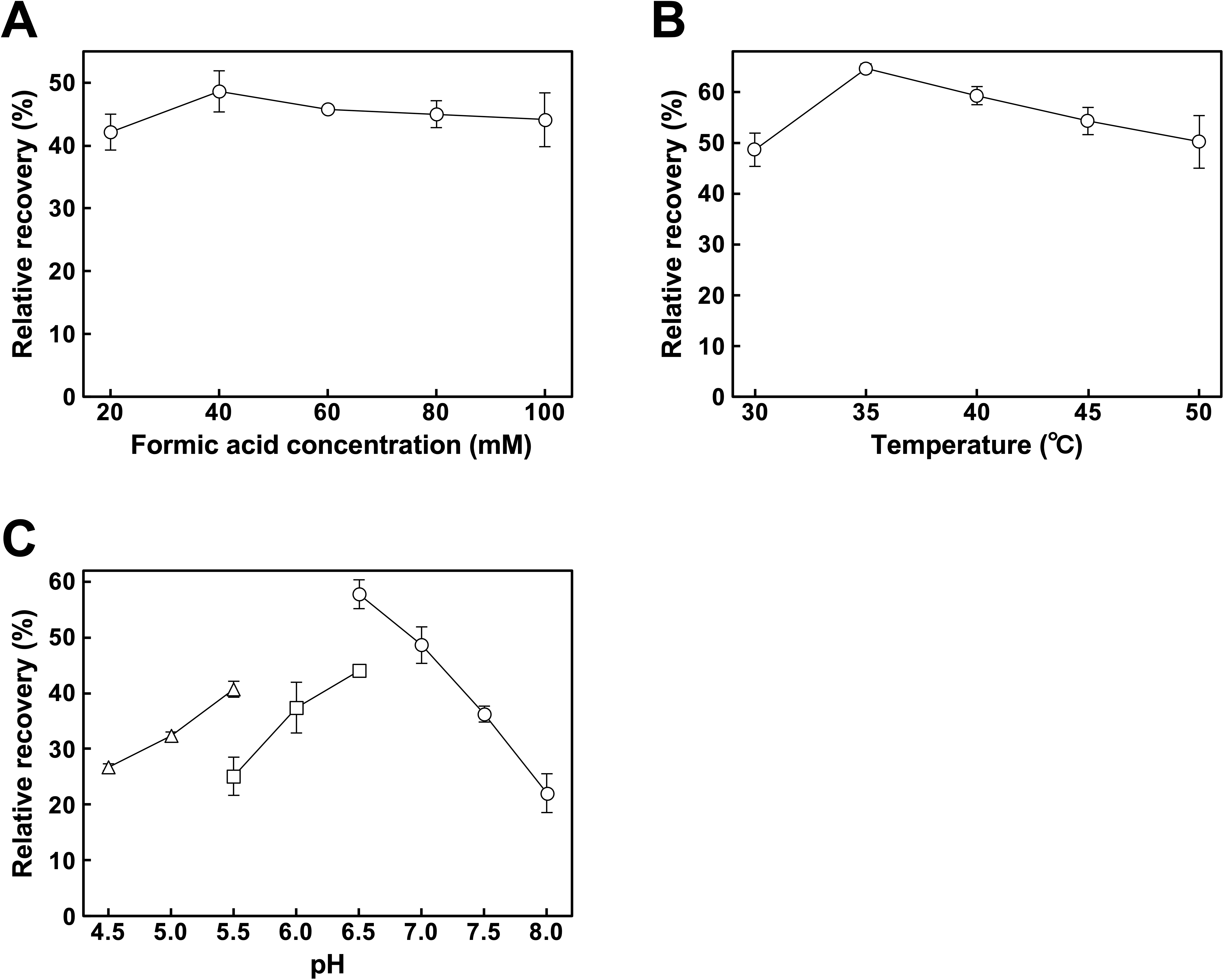

3.2. Optimization of Palladium Recovery

3.3. Estimation of Mechanism for Palladium Biomineralization

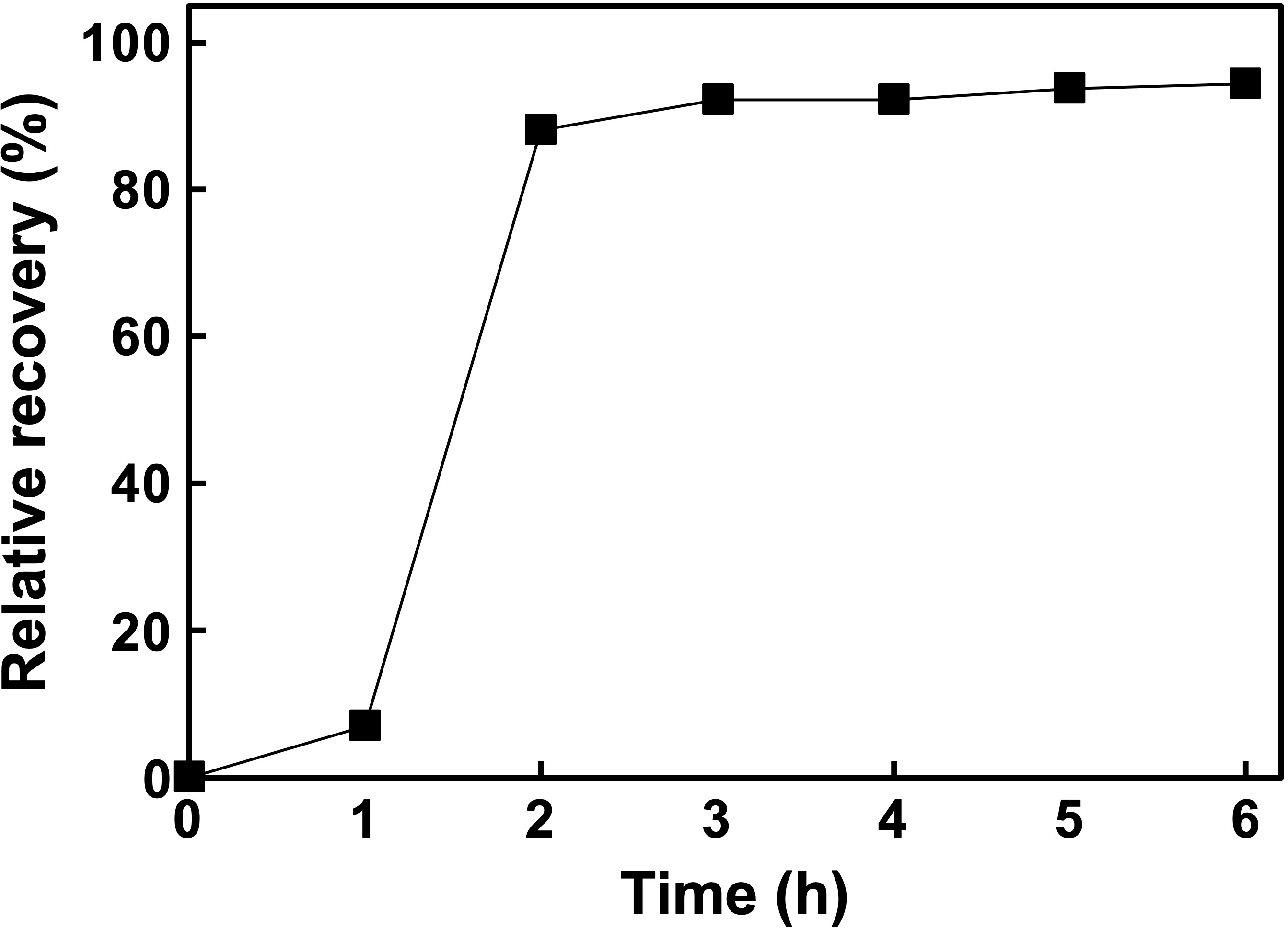

3.4. Palladium Recovery from e-Waste

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cao, Y.; Ran, R.; Wu, X.; Si, Z.; Kang, F.; Weng, D. Progress on metal-support interactions in Pd-based catalysts for automobile emission control. J. Environ. Sci. 2023, 125, 401–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alentiev, D.A.; Bermeshev, M.V.; Volkov, A.V.; Petrova, I.V.; Yaroslavtsev, A.B. Palladium membrane applications in hydrogen energy and hydrogen-related processes. Polymers 2025, 17, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biffis, A.; Centomo, P.; Del Zotto, A.; Zecca, M. Pd metal catalysts for cross-couplings and related reactions in the 21st century: A critical review. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 2249–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherepovitsyn, A.; Mekerova, I.; Nevolin, A. Analysis of the Palladium Market: A strategic aspect of sustainable development. Mining 2025, 5, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Ogunseitan, O.A. Disentangling the worldwide web of e-waste and climate change co-benefits. Circ. Econ. 2022, 1, 100011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adetunji, A.I.; Oberholster, P.J.; Erasmus, M. Bioleaching of metals from e-waste using microorganisms: A review. Minerals 2023, 13, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, D.; Goel, S.; Kumar, S. Health risk assessment for exposure to heavy metals in soils in and around E-waste dumping site. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 107269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.K.; Ellamparuthy, G.; Kundu, T.; Angadi, S.I.; Rath, S.S. A comprehensive review of the mechanical separation of waste printed circuit boards. Proc. Safety Environ. Prot. 2024, 187, 221–239. [Google Scholar]

- Binnemans, K.; Jones, P.T.; Manjón Fernández, Á.M.; Torres, V.M. Hydrometallurgical processes for the recovery of metals from steel industry by-products: A critical review. J. Sustain. Metall. 2020, 6, 505–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgeois, D.; Lacanau, V.; Mastretta, R.; Contino-Pépin, C.; Meyer, D. A simple process for the recovery of palladium from wastes of printed circuit boards. Hydrometallurgy 2020, 191, 105241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pande, V.; Pandey, S.C.; Sati, D.; Bhatt, P.; Samant, M. Microbial interventions in bioremediation of heavy metal contaminants in agroecosystem. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 824084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adewuyi, A. Chemically modified biosorbents and their role in the removal of emerging pharmaceutical waste in the water system. Water 2020, 12, 1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, R.K.; Nayak, M.; Parhi, P.K.; Pandey, S.; Thatoi, H.; Panda, C.R.; Choi, Y. Biosorption performance and mechanism insights of live and dead biomass of halophilic Bacillus altitudinis strain CdRPSD103 for removal of Cd(II) from aqueous solution. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2024, 191, 105811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawwam, G.E.; Abdelfattah, N.M.; Abdel-Monem, M.O.; Jahin, H.S.; Omer, A.M.; Abou-Taleb, K.A.; Mansor, E.S. An immobilized biosorbent from Paenibacillus dendritiformis dead cells and polyethersulfone for the sustainable bioremediation of lead from wastewater. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konishi, Y.; Tsukiyama, T.; Saitoh, N.; Nomura, T.; Nagamine, S.; Takahashi, Y.; Uruga, T. Direct determination of oxidation state of gold deposits in metal-reducing bacterium Shewanella algae using X-ray absorption near-edge structure spectroscopy (XANES). J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2007, 103, 568–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saitoh, N.; Fujimori, R.; Nakatani, M.; Yoshihara, D.; Nomura, T.; Konishi, Y. Microbial recovery of gold from neutral and acidic solutions by the baker’s yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Hydrometallurgy 2018, 181, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akita, H.; Matsushika, A.; Kimura, Z.I. Enterobacter oligotrophica sp. nov., a novel oligotroph isolated from leaf soil. Microbiologyopen 2019, 8, e00843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akita, H.; Kumagai, A. Biosorption of palladium using Enterobacter oligotrophicus CCA6T. Salt Seawat. Sci. Technol. 2021, 2, 19–21. [Google Scholar]

- Creamer, N.J.; Baxter-Plant, V.S.; Henderson, J.; Potter, M.; Macaskie, L.E. Palladium and gold removal and recovery from precious metal solutions and electronic scrap leachates by Desulfovibrio desulfuricans. Biotechnol. Lett. 2006, 28, 1475–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deplanche, K.; Caldelari, I.; Mikheenko, I.P.; Sargent, F.; Macaskie, L.E. Involvement of hydrogenases in the formation of highly catalytic Pd(0) nanoparticles by bioreduction of Pd(II) using Escherichia coli mutant strains. Microbiology 2010, 156, 2630–2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, M.; Wieczorek, G.; Rosenne, S.; Tawfik, D.S. The universality of enzymatic rate–temperature dependency. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2014, 39, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benoit, S.; Abaibou, H.; Mandrand-Berthelot, M.A. Topological analysis of the aerobic membrane-bound formate dehydrogenase of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1998, 180, 6625–6634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Axley, M.J.; Grahame, D.A.; Stadtman, T.C. Escherichia coli formate-hydrogen lyase. Purification and properties of the selenium-dependent formate dehydrogenase component. J. Biol. Chem. 1990, 265, 18213–18218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidyadhar, A. A Review of Technology of Metal Recovery from Electronic Waste; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2016; pp. 1–190. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto, T.; Kamino, M.; Yamada, R.; Konishi, Y.; Ogino, H. Identification of genes responsible for reducing palladium ion in Escherichia coli. J. Biotechnol. 2020, 324, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joudeh, N.; Saragliadis, A.; Schulz, C.; Voigt, A.; Almaas, E.; Linke, D. Transcriptomic response analysis of Escherichia coli to palladium stress. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 741836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, E.; Maeda, K.; Kamemoto, Y.; Hirai, K.; Apdila, E.T. Contribution to a sustainable society: Biosorption of precious metals using the microalga Galdieria. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Function | Gene | Protein |

|---|---|---|

| Formate metabolism | fdhD | Formate dehydrogenase accessory sulfurtransferase |

| fdhE | Formate dehydrogenase accessory protein | |

| moaC | Cyclic pyranopterin monophosphate synthase | |

| Molybdenum transport/molybdopterin synthesis | moaD | Molybdopterin synthase sulfur carrier subunit |

| moaE | Molybdopterin synthase catalytic subunit | |

| mobA | Molybdenum cofactor guanylyltransferase | |

| modC | Molybdenum ABC transporter ATP-binding protein | |

| moeA | Molybdopterin molybdotransferase | |

| moeB | Molybdopterin synthase adenylyltransferase | |

| Other metabolisms | hypA | Hydrogenase maturation nickel metallochaperone |

| mak | Fructokinase | |

| pykF | Pyruvate kinase | |

| pyrF | Orotidine 5’-phosphate decarboxylase | |

| rpiA | Ribose 5-phosphate isomerase | |

| selD | Selenide, water dikinase | |

| sucA | 2-Oxoglutarate dehydrogenase E1 component | |

| sufD | Fe-S cluster assembly protein | |

| tpx | Thiol peroxidase | |

| ubiG | Bifunctional 2-polyprenyl-6-hydroxyphenol methylase/3-demethylubiquinol 3-O-methyltransferase | |

| ubiE | Bifunctional demethylmenaquinone methyltransferase/2-methoxy-6-polyprenyl-1,4-benzoquinol methylase | |

| Membrane protein | aaeA | p-Hydroxybenzoic acid efflux pump subunit |

| aroP | Aromatic amino acid transporter | |

| fliE | Flagellar hook-basal body complex protein | |

| glnP | Glutamine ABC transporter permease | |

| oppD | Murein tripeptide ABC transporter/Oligopeptide ABC transporter ATP-binding protein | |

| yadK | Fimbrial-like protein | |

| yecC | L-Cystine ABC transporter ATP-binding protein | |

| yfjD | Inner membrane protein | |

| Regulation of DNA expression | holC | DNA polymerase III subunit χ |

| ogt | Methylated-DNA-[protein]-cysteine S-methyltransferase | |

| Uncharacterized | rarA | Replication-associated recombination protein |

| yceG | Cell division protein | |

| ypeC | DUF2502 domain-containing protein |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Akita, H. Palladium Recovery from e-Waste Using Enterobacter oligotrophicus CCA6T. Fermentation 2026, 12, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation12010003

Akita H. Palladium Recovery from e-Waste Using Enterobacter oligotrophicus CCA6T. Fermentation. 2026; 12(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation12010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleAkita, Hironaga. 2026. "Palladium Recovery from e-Waste Using Enterobacter oligotrophicus CCA6T" Fermentation 12, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation12010003

APA StyleAkita, H. (2026). Palladium Recovery from e-Waste Using Enterobacter oligotrophicus CCA6T. Fermentation, 12(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation12010003