Advances in Third-Generation Bioethanol Production, Industrial Infrastructure and Efficient Technologies in Sustainable Processes with Algae Biomass: Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Scope of the Literature Review

2.1. Industrial Systems and Sustainability

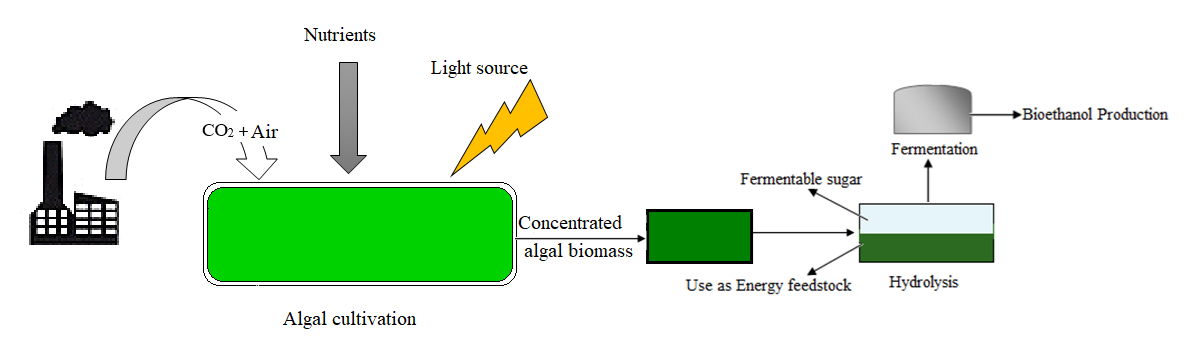

2.2. Processes Involved in Obtaining Third-Generation Biofuels

3. Methodology—The Methodological Framework

3.1. Methodological Design and PRISMA Protocol

3.2. Reporting Guidelines

4. Infrastructure and Industrial Technology

4.1. Advancement in Algae Feedstock for Biofuel Production

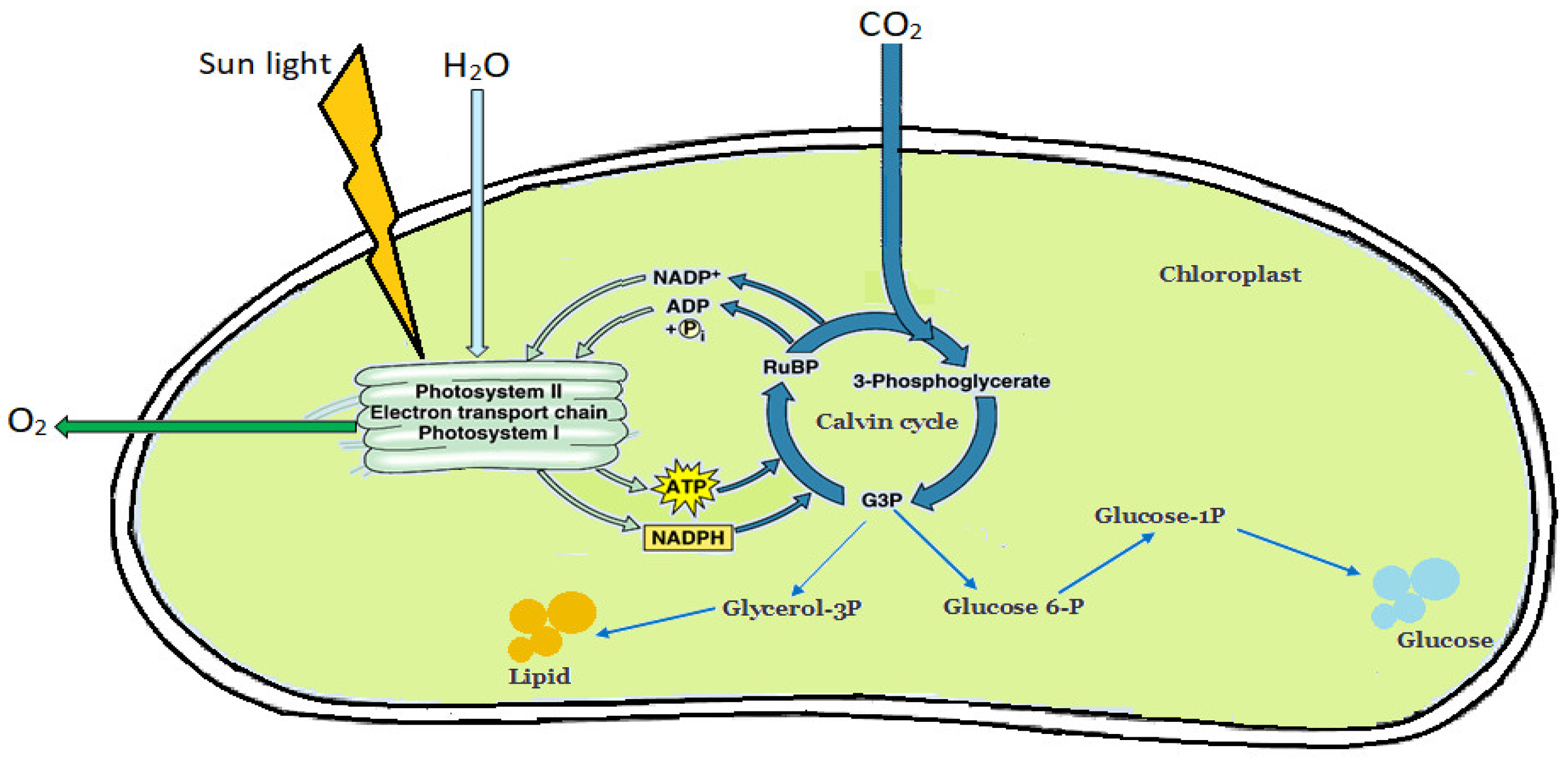

4.2. Harnessing Microalgae for Bioethanol Production

| Microalgae Strain | Stress Factor | Effect on Carbohydrate/Starch Accumulation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chlorella protothecoides Kruger (CCAP 211/8D) | Nutrient-limited conditions (both nitrogen and iron are limited) | Carbohydrate content 41% by dry mass | [81] |

| Chlorella vulgaris Beijerinck (CCAP 211/11B) | Nutrient-limited conditions (both nitrogen and iron are limited) | Carbohydrate content 55 wt.% by dry mass | [81] |

| Chlorella vulgaris (P12 41) | Nutrient-limited conditions (both nitrogen and iron are limited) | Starch content 41 wt.% by dry mass | [14] |

| Spirodela polyrhiza (ZH0196) | Nutrient-limited conditions | Starch content increased by 39.8 wt.% in 2 days | [82] |

| Spirodela polyrhiza | Nutrient starvation and abscisic acid (synergistic effect) | Starch content increased to 38.3 ± 1.9 wt.% (dry weight) | [83] |

| Spirulina | Presence of nitrates and phosphates in wastewater | Carbohydrate content up to 48.4 ± 2.9 wt.% | [84] |

| Scenedesmus obliquus | Nitrogen-limited conditions | Carbohydrate content 62.5 wt.% by dry mass | [85] |

| Chlorococcum humicola | Nutrient-limited conditions (both phosphorus and sulphur are limited) | Starch content 60 wt.% by dry mass | [86] |

| Chlorella vulgaris | Light stress, 140 μmol photons·m−2·s−1 with 7.5 g·L−1 NaCl/7.5 g·L−1 CaCl2 | Carbohydrate content 52.71 wt.% by dry mass | [87] |

| Chlamydomonas sp. | Light stress, 750 μmol photons∙m−2∙s−1 | Carbohydrate content 63 wt.% by dry mass | [81] |

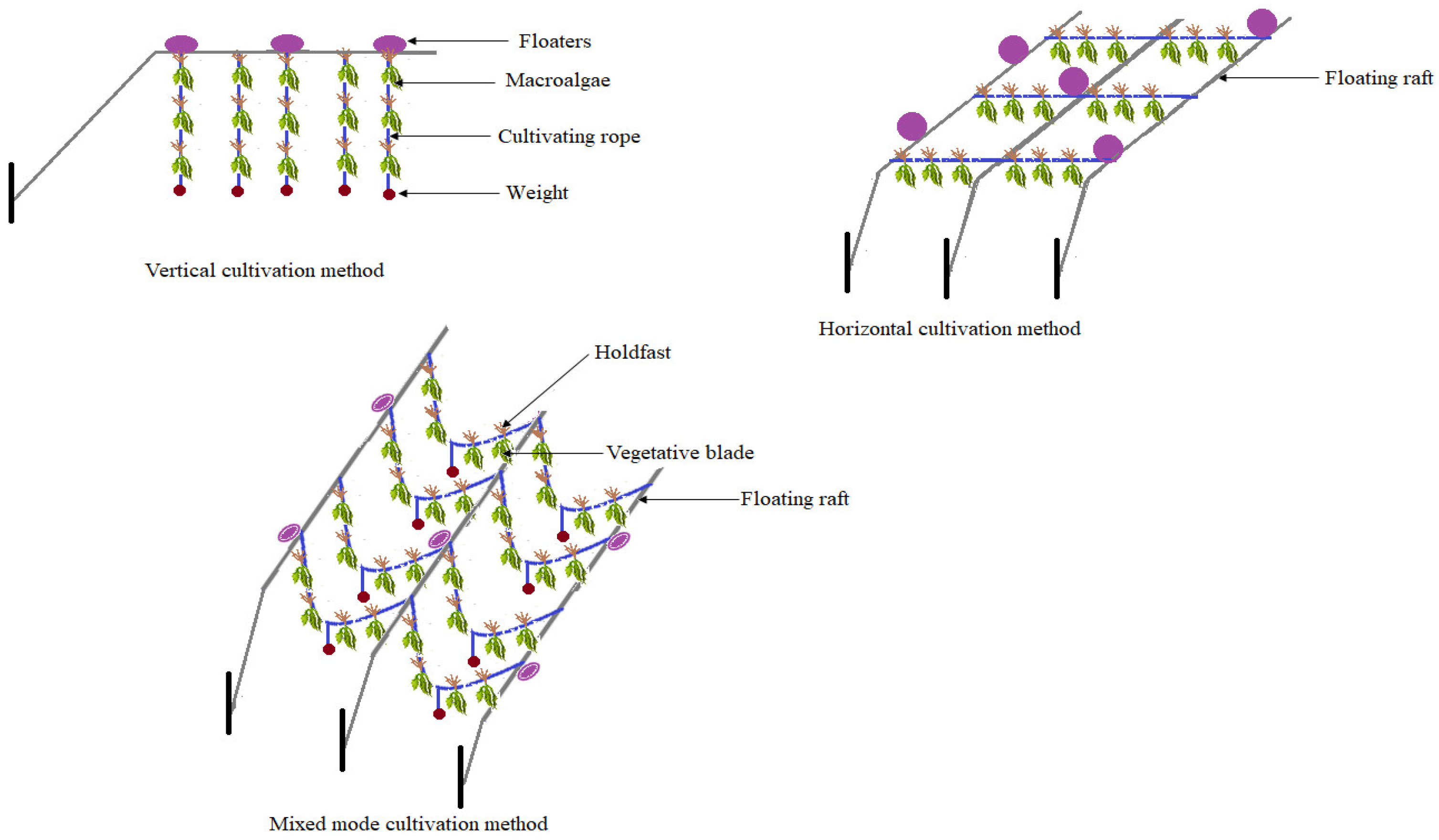

4.3. Harnessing Macroalgae for Bioethanol Production

5. Processes Involved in the Manufacturing of Third-Generation Biofuels

5.1. Technologies in Biofuel Production

5.2. Selection of Efficient Technologies for Third-Generation Bioethanol Production

6. Global Trends in the Production of Bioethanol from Algae

7. Price Comparison of Third-Generation Bioethanol from Microalgae vs. Macroalgae (Seaweeds)

8. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Meaning |

| C. shehatae | Candida shehatae |

| MJ∙kg−1 | Megajoules per kilogram |

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide |

| mL∙hL−1 | Milliliters per hectoliter |

| 3G | Third generation |

| mL/0.5 L | Milliliters per half liter |

| GHG | Greenhouse gases |

| GHE | Greenhouse gas emissions |

| mL∙(μg Chl a)−1 | Milliliters per microgram of Chlorophyll a |

| SLR | Systematic literature review |

| LCH4∙gVS−1 | Liters of methane per gram of volatile solids |

| % | Percentage by mass |

| VAPs | Value-added products |

References

- Osman, A.I.; Qasim, U.; Jamil, F.; Ala’a, H.; Jrai, A.A.; Al-Riyami, M.; Al-Maawali, S.; Al-Haj, L.; Al-Hinai, A.; Al-Abri, M. Bioethanol and biodiesel: Bibliometric mapping, policies and future needs. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 152, 111677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csutora, M.; Mózner, Z.V. Carbon management strategies of the automotive sector responding to the European fleet-wide CO2 emission targets. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altarazi, Y.S.M.; Abu Talib, A.R.; Yu, J.; Gires, E.; Abdul Ghafir, M.F.; Lucas, J.; Yusaf, T. Effects of biofuel on engines performance and emission characteristics: A review. Energy 2022, 238, 121910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandra, T.; Saranya, G. Sustainable Bioeconomy prospects of diatom biorefineries in the Indian west coast. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 161, 112399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabłońska-Trypuć, A.; Wołejko, E.; Ernazarovna, M.D.; Głowacka, A.; Sokołowska, G.; Wydro, U. Using algae for biofuel production: A review. Energies 2023, 16, 1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizik, T. European Union guidelines for the production of different generations of biofuels. In Biofuels and Sustainability; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; pp. 205–219. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, Y.; Dai, Y.; Xue, S.; Yi, Z.; Chen, Z.; Li, M.; von Cossel, M. Organic Acid-Based Hemicellulose Fractionation and Cellulosic Ethanol Potential of Five Miscanthus Genotypes. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Malhotra, P.; Goel, A.; Sharma, P.; Sanghera, G.S.; Kaur, G. From First-to Fourth-Generation Biofuels: Prospects and Challenges. In Climate-Smart Sugarcane Cultivation; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2025; p. 157. [Google Scholar]

- de Paula Leite, A.C.; Pimentel, L.M.; de Almeida Monteiro, L. Biofuel adoption in the transport sector: The impact of renewable energy policies. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2025, 81, 104419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarri, J.H.; Imlan, K.H.; Ahajan, N.A.; Hairol, M.D.; Kissae, A.-N.H.; Yangson, N.A.T.; Robles, R.J.F.; Talaid, E.M. Application of Marine Plant Extract Powder (AMPEP) as a Nutrient Supplement for Optimizing Nannochloropsis sp. Cultivation. Isr. J. Aquac.-Bamidgeh 2025, 77, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindhu, R.; Binod, P.; Pandey, A.; Ankaram, S.; Duan, Y.; Awasthi, M.K. Biofuel production from biomass: Toward sustainable development. In Current Developments in Biotechnology and Bioengineering; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 79–92. [Google Scholar]

- Akolkar, H.N.; Haghi, A.; Darekar, N.R.; Pawar, G.B. Bioenergy from Microalgal Biomass: Sustainable Conversion Technologies; Synthesis Lectures on Renewable Energy Technologies; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Z.; Cheah, W.Y.; Ng, I.-S.; Chang, J.-S.; Zhao, M.; Show, P.L. Microalgae-based biotechnological sequestration of carbon dioxide for net zero emissions. Trends Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 1439–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, S.K.; Kim, G.; Song, H. Algae to Biofuels: Catalytic Strategies and Sustainable Technologies for Green Energy Conversion. Catalysts 2025, 15, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Liu, Y.; Deng, Z.; Xie, X.; Yang, C.; Baloch, H.; Qin, Z.; Xu, W.; Zhang, H.; Gao, J. The potential microalgae-based strategy for attaining carbon neutrality and mitigating climate change: A critical review. Front. Mar. Sci. 2025, 12, 1644390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Lei, X.; Zou, T.; Zhang, Z.; Wen, S.; He, X. Feasibility of using lipid-rich mutant microalgae in wastewater cultivation: Biochemical changes, nutrient removal, and lipid analysis. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 115213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Romero, C.I.; Olguín, E.J.; Elizondo-González, R.; Rodríguez, A.P.; Arredondo-Vega, B.O. Mixotrophic culture of microalgae: A review [Cultivo mixotrófico de microalgas: Una revisión]. Rev. Latinoam. Biotecnol. Ambient. Algal 2025, 16, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Pant, S.; Goel, M.; Sahoo, N.K.; Yuan, Q.; Rout, P.R. Microalgae-based treatment for wastewater management and valorisation. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2025, 48, 100662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreelakshmi, M.; Arunkumar, K. Microalgal Neutral Lipid Accumulation: Cellular Mechanism and Ways to Improve Biodiesel Production. BioEnergy Res. 2025, 18, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Shaukat, A.; Azhar, W.; Raza, Q.-U.-A.; Tahir, A.; Abideen, M.Z.u.; Zia, M.A.B.; Bashir, M.A.; Rehim, A. Microalgal biorefineries: A systematic review of technological trade-offs and innovation pathways. Biotechnol. Biofuels Bioprod. 2025, 18, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadudvari, A.; Schagerl, M.; Ancheta, S.M. Possible Effects of Pesticide Washout on Microalgae Growth. Water 2025, 17, 2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhandama, M.V.L.; Ruatpuia, J.V.; Ao, S.; Chetia, A.C.; Satyan, K.B.; Rokhum, S.L. Microalgae as a sustainable feedstock for biodiesel and other production industries: Prospects and challenges. Energy Nexus 2023, 12, 100255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Dalania, K.; Magotra, S.; Singh, A.K.; Negi, N.P. Sustainable energy solutions: The role of biotechnology and algal biofuels in environmental preservation. Discov. Biotechnol. 2025, 2, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coons, J.; Yap, B.; Gasway, C.; Bischoff, B.; Sweeney, N.; Dong, T.; Pienkos, P.; Sanders, C.; Dale, T. The energy costs of dewatering feedstock microalgae species using standard implementations of ultrasonic and crossflow filtration technologies. SSRN 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janda, K.; Kristoufek, L.; Zilberman, D. Biofuels: Policies and impacts. Agric. Econ. 2012, 58, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofili, M. Biofuel & biorefinery portfolios of petroleum companies–Policy & nomenclature implications. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. Res. 2025, 9, em0302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guedes, A.C.; Amaro, H.M.; Sousa-Pinto, I.; Malcata, F.X. Algal spent biomass—A pool of applications. In Biofuels from Algae; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 397–433. [Google Scholar]

- Hull, T.C.; Knoshaug, E.P.; Nelson, R.S.; Van Wychen, S.; Nagle, N.; Kruger, J.S.; Dong, T. Integrated thermal and biological conversion of microalgal proteins to lipids. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 435, 132927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, J.; Unlu, S.; Demirel, Y.; Black, P.; Riekhof, W. Integration of biology, ecology and engineering for sustainable algal-based biofuel and bioproduct biorefinery. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2018, 5, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paladino, O.; Neviani, M. Scale-up of algal bioreactors for renewable resource production. In Algal Bioreactors; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; pp. 281–301. [Google Scholar]

- Chew, K.W.; Yap, J.Y.; Show, P.L.; Suan, N.H.; Juan, J.C.; Ling, T.C.; Lee, D.-J.; Chang, J.-S. Microalgae biorefinery: High value products perspectives. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 229, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsalan, S.; Zubair, S. Suitable site analysis for microalgae biofuel production as a source of renewable energy. Biofuels 2025, 16, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraldo-Calderón, N.D.; Romo-Buchelly, R.J.; Arbeláez-Pérez, A.A.; Echeverri-Hincapié, D.; Atehortúa-Garcés, L. Microalgae biorefineries: Applications and emerging technologies. Dyna 2018, 85, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, T.Y.; Cheah, S.A.; Ong, C.T.; Wong, L.Y.; Goh, C.R.; Tan, I.S.; Foo, H.C.Y.; Lam, M.K.; Lim, S. Techno-economic evaluation of third-generation bioethanol production utilizing the macroalgae waste: A case study in Malaysia. Energy 2020, 210, 118491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bhowmick, G.; Sarmah, A.K.; Sen, R. Zero-waste algal biorefinery for bioenergy and biochar: A green leap towards achieving energy and environmental sustainability. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 650, 2467–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, M.G.; Dosoky, N.S.; Zoromba, M.S.; Shafik, H.M. Algal biofuels: Current status and key challenges. Energies 2019, 12, 1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onn, S.M.; Koh, G.J.; Yap, W.H.; Teoh, M.-L.; Low, C.-F.; Goh, B.-H. Recent advances in genetic engineering of microalgae: Bioengineering strategies, regulatory challenges and future perspectives. J. Appl. Phycol. 2025, 37, 247–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochenski, T.; Chaturvedi, T.; Thomsen, M.H.; Schmidt, J.E. Evaluation of marine synechococcus for an algal biorefinery in arid regions. Energies 2019, 12, 2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zollmann, M.; Robin, A.; Prabhu, M.; Polikovsky, M.; Gillis, A.; Greiserman, S.; Golberg, A. Green technology in green macroalgal biorefineries. Phycologia 2019, 58, 516–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.S.; Kornaros, M.; Al-Tohamy, R.; Sun, J.; El-Sheekh, M.M.; Lim, J.W. Bottleneck and opportunities toward practical aspects of microalgae-based biorefineries. In Algal Biorefinery; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; pp. 325–333. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah, M.; Malik, H.A.; Ali, A.; Boopathy, R.; Vo, P.H.; Danaee, S.; Ralph, P.; Malik, S. AI-driven algae biorefineries: A new era for sustainable bioeconomy. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2025, 11, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeswani, H.K.; Chilvers, A.; Azapagic, A. Environmental sustainability of biofuels: A review. Proc. R. Soc. A 2020, 476, 20200351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nashath, F.Z.; Ng, Y.J.; Khoo, K.S.; Show, P.L. Current contributions of microalgae in global biofuel production; cultivation techniques, biofuel varieties and promising industrial ventures. Biomass Bioenergy 2025, 201, 108092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, R.; Dewangan, A.K.; Yadav, A.K.; Yadav, B. Recent advancements in biomass conversion technologies for renewable energy generation and achieving net-zero carbon emissions. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2025, 150, 17989–18005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jathar, L.; Kolhe, M.; Patil, J.; Awasarmol, U. Harnessing microalgae for sustainable biofuel: Integration of biochemical conversion, AI/ML applications and life cycle analysis. Int. J. Ambient. Energy 2025, 46, 2543914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, B.D.; Bhattarai, A. The versatility of algae in addressing the global sustainability challenges. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2025, 13, 1621817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, H. Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen-Zanker, J.; Mallett, R. How to Do a Rigorous, Evidence-Focused Literature Review in International Development; ODI: London, UK, 2013; Available online: https://media.odi.org/documents/8572.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makepa, D.C.; Chihobo, C.H. Sustainable pathways for biomass production and utilization in carbon capture and storage—A review. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2025, 15, 11397–11419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olabi, A.; Alami, A.H.; Alasad, S.; Aljaghoub, H.; Sayed, E.T.; Shehata, N.; Rezk, H.; Abdelkareem, M.A. Emerging technologies for enhancing microalgae biofuel production: Recent progress, barriers, and limitations. Fermentation 2022, 8, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, I.; Pandey, S.; Vinayagam, R.; Selvaraj, R.; Varadavenkatesan, T. A recent update on enhancing lipid and carbohydrate accumulation for sustainable biofuel production in microalgal biomass. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2025, 7, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levasseur, W.; Perré, P.; Pozzobon, V. A review of high value-added molecules production by microalgae in light of the classification. Biotechnol. Adv. 2020, 41, 107545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deviram, G.; Mathimani, T.; Anto, S.; Ahamed, T.S.; Ananth, D.A.; Pugazhendhi, A. Applications of microalgal and cyanobacterial biomass on a way to safe, cleaner and a sustainable environment. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 253, 119770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hena, S.; Znad, H.; Heong, K.; Judd, S. Dairy farm wastewater treatment and lipid accumulation by Arthrospira platensis. Water Res. 2018, 128, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Guo, L.; Gao, M.; Zhao, Y.; Jin, C.; She, Z. Regulation of carbon source metabolism in mixotrophic microalgae cultivation in response to light intensity variation. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 302, 114095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, A.F.; Salgado, E.M.; Vilar, V.J.; Gonçalves, A.L.; Pires, J.C. A growth phase analysis on the influence of light intensity on microalgal stress and potential biofuel production. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 311, 118511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.H.; Kondo, A.; Hasunuma, T.; Chang, J.S. Engineering strategies for improving the CO2 fixation and carbohydrate productivity of Scenedesmus obliquus CNW-N used for bioethanol fermentation. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 143, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, T.; Xia, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y. Nitrate concentration-shift cultivation to enhance protein content of heterotrophic microalga Chlorella vulgaris: Over-compensation strategy. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 233, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Feng, J.; Lv, J.; Liu, Q.; Nan, F.; Liu, X.; Xie, S. Physiological changes of Parachlorella kessleri ty02 in lipid accumulation under nitrogen stress. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, S.; Wang, Y.; Huang, W.; Xu, J.; Wang, Z.; Xu, J.; Yuan, Z. Enhanced accumulation of carbohydrate and starch in Chlorella zofingiensis induced by nitrogen starvation. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2014, 174, 2435–2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Şirin, P.A.; Serdar, S. Effects of nitrogen starvation on growth and biochemical composition of some microalgae species. Folia Microbiol. 2024, 69, 889–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markou, G. Alteration of the biomass composition of Arthrospira (Spirulina) platensis under various amounts of limited phosphorus. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 116, 533–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.Y.; Chang, H.Y.; Chang, J.S. Producing carbohydrate-rich microalgal biomass grown under mixotrophic conditions as feedstock for biohydrogen production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 4413–4420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jati, B.N.; Nuraeni, C.; Yunilawati, R.; Oktarina, E. Phytochemical screening and total lipid content of marine macroalgae from Binuangeun beach. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1317, 012103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beigbeder, J.B.; Lavoie, J.M. Effect of photoperiods and CO2 concentrations on the cultivation of carbohydrate-rich P. kessleri microalgae for the sustainable production of bioethanol. J. CO2 Util. 2022, 58, 101934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Han, W.; Li, P.; Miao, X.; Zhong, J. CO2 biofixation and fatty acid composition of Scenedesmus obliquus and Chlorella pyrenoidosa in response to different CO2 levels. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 3071–3076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, B.C.B.; Morais, M.G.; Costa, J.A.V. Chlorella minutissima grown with xylose and arabinose in tubularphotobioreactors: Evaluation of kinetics, carbohydrate production, and protein profile. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2022, 100, S49–S57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arena, R.; Lima, S.; Villanova, V.; Moukri, N.; Curcuraci, E.; Messina, C.; Santulli, A.; Scargiali, F. Cultivation and biochemical characterization of isolated Sicilian microalgal species in salt and temperature stress conditions. Algal Res. 2021, 59, 102430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Chen, J.; Liu, C.; Zhuo, X.; Luo, Y.; Li, Y.; Huang, D.; Zhu, H.; Hu, Z.; Lou, S.; et al. Potential of a novel marine microalgae Dunaliella sp. MASCC-0014 as feed supplements for sustainable aquaculture. Aquaculture 2025, 596, 741732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-García, A.; Velásquez-Orta, S.B.; Novelo, E.; Yáñez-Noguez, I.; Monje-Ramírez, I.; Ledesma, M.T.O. Wastewater-leachate treatment by microalgae: Biomass, carbohydrate and lipid production. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 174, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chokshi, K.; Pancha, I.; Ghosh, A.; Mishra, S. Salinity induced oxidative stress alters the physiological responses and improves the biofuel potential of green microalgae Acutodesmus dimorphus. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 244, 1376–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Chelak, P.; Das, M.; Jha, M.K.; Das, A. Stress-induced enhancement of microalgal biochemical composition for sustainable biorefineries. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2025, 7, 1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Contreras, M.I.; Morales-Arrieta, S.; Okoye, P.U.; Guillén-Garcés, R.A.; Sebastian, P.; Arias, D.M. Recycling industrial wastewater for improved carbohydrate-rich biomass production in a semi-continuous photobioreactor: Effect of hydraulic retention time. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 284, 112065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Freitas, B.C.B.; Brächer, E.H.; de Morais, E.G.; Atala, D.I.P.; de Morais, M.G.; Costa, J.A.V. Cultivation of different microalgae with pentose as carbon source and the effects on the carbohydrate content. Environ. Technol. 2019, 40, 1062–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.; Li, D.; Yuan, Y.; Zhou, L.; Li, X.; Wu, T.; Wang, L.; Zhao, Q.; Wei, W.; Sun, Y. Improving carbohydrate and starch accumulation in Chlorella sp. AE10 by a novel two-stage process with cell Dilution. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2017, 10, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hena, S.; Gutierrez, L.; Croué, J.P. Removal of pharmaceutical and personal care products (PPCPs) from wastewater using microalgae: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 403, 124041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho Silvello, M.A.; Goncalves, I.S.; Azambuja, S.P.H.; Costa, S.S.; Silva, P.G.P.; Santos, L.O.; Goldbeck, R. Microalgae-based carbohydrates: A green innovative source of bioenergy. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 344, 126304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, W.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Ho, S.-H. Optimizing real swine wastewater treatment with maximum carbohydrate production by a newly isolated indigenous microalga Parachlorella kessleri QWY28. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 289, 121702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, W.; Show, P.L.; Hasunuma, T.; Ho, S.-H. Optimizing real swine wastewater treatment efficiency and carbohydrate productivity of newly microalga Chlamydomonas sp. QWY37 used for cell-displayed bioethanol production. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 305, 123072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Illman, A.; Scragg, A.; Shales, S. Increase in Chlorella strains calorific values when grown in low nitrogen medium. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2000, 27, 631–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, X.; Hong, Y.; Fang, Y.; Cheng, L.; Li, Z.; Li, C.; Ban, X. Transcriptomic and Metabolic Analysis Reveal Potential Mechanism of Starch Accumulation in Spirodela polyrhiza Under Nutrient Stress. Plants 2025, 14, 1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Q.; Zhang, Y.-Q.; Tan, A.-J.; Li, Z.; Yang, G.-L. Synergistic effect of nutrient starvation and abscisic acid on growth and starch accumulation in duckweed. Planta 2025, 261, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunwong, S.; Vinitnantharat, S.; Hongsthong, A. Dilution rate caused nutrient limitation effects on the biomass composition and proteomic level of continuously cultivated Spirulina in recirculating aquaculture system wastewater. J. Water Process Eng. 2025, 69, 106734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, M.L.; Soares, J.; Vieira, B.B.; Batista-Silva, W.; Martins, M.A. Extraction of proteins from the microalga Scenedesmus obliquus BR003 followed by lipid extraction of the wet deproteinized biomass using hexane and ethyl acetate. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 307, 123190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narchonai, G.; Arutselvan, C.; LewisOscar, F.; Thajuddin, N. Enhancing starch accumulation/production in Chlorococcum humicola through sulphur limitation and 2,4-D treatment for butanol production. Biotechnol. Rep. 2020, 28, e00528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-fayoumy, E.A.; Ali, H.E.A.; Elsaid, K.; Elkhatat, A.; Al-Meer, S.; Rozaini, M.Z.H.; Abdullah, M.A. Co-production of high density biomass and high-value compounds via two-stage cultivation of Chlorella vulgaris using light intensity and a combination of salt stressors. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2024, 14, 22673–22686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, W.S.; Bao, Y.; Jin, P.; Tang, G.; Zhou, L. A review on ammonia, ammonia-hydrogen and ammonia-methane fuels. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 147, 111254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.Y.Y.; Khoo, K.S.; Chew, K.W.; Tao, Y.; Ho, S.-H.; Show, P.L. Potential utilization of bioproducts from microalgae for the quality enhancement of natural products. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 304, 122997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazar, L.; Vlas, O.; Pantea, E.; Boicenco, L.; Marin, O.; Abaza, V.; Filimon, A.; Bisinicu, E. Black sea eutrophication comparative analysis of intensity between coastal and offshore waters. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Pugazhendi, A.; Bajhaiya, A.K.; Gugulothu, P. Biofuel production from Macroalgae: Present scenario and future scope. Bioengineered 2021, 12, 9216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, B.F.R.; Freitas-Silva, J.; Sánchez-Robinet, C.; Laport, M.S. Transmission of the sponge microbiome: Moving towards a unified model. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2020, 12, 619–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamilarasan, K.; Banu, J.R.; Kumar, M.D.; Sakthinathan, G.; Park, J.-H. Influence of mild-ozone assisted disperser pretreatment on the enhanced biogas generation and biodegradability of green marine macroalgae. Front. Energy Res. 2019, 7, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraai, J.A.; Rorrer, G.L. Immobilization and growth of clonal tissue fragments from the macrophytic red alga Gracilaria vermiculophylla on porous mesh panels. J. Appl. Phycol. 2021, 33, 2407–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, F.; Tarbuck, P.; Macreadie, P.I. Seaweed afforestation at large-scales exclusively for carbon sequestration: Critical assessment of risks, viability and the state of knowledge. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 1015612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froehlich, H.E.; Afflerbach, J.C.; Frazier, M.; Halpern, B.S. Blue growth potential to mitigate climate change through seaweed offsetting. Curr. Biol. 2019, 29, 3087–3093.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, P.W.; Bach, L.T.; Hurd, C.L.; Paine, E.; Raven, J.A.; Tamsitt, V. Potential negative effects of ocean afforestation on offshore ecosystems. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 6, 675–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsiglia, N.; Bosch-Belmar, M.; Mancuso, F.P.; Sarà, G. Epibionts and Epiphytes in Seagrass Habitats: A Global Analysis of Their Ecological Roles. Sci 2025, 7, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alevizos, E.; Barille, L. Global ocean spatial suitability for macroalgae offshore cultivation and sinking. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1320642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dębowski, M.; Kazimierowicz, J.; Zieliński, M. Multi-Sensing Monitoring of the Microalgae Biomass Cultivation Systems for Biofuels and Added Value Products Synthesis—Challenges and Opportunities. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nur, K.U.; Saade, E.; Rusdi, I.; Mokka, W.; Haramain, M. Partial inclusion of macroalgae into formulated feed to induce gonad maturation in tropical abalone, Haliotis squamata, broodstock. Aquac. Aquar. Conserv. Legis. 2025, 18, 200–209. [Google Scholar]

- Ismail, M.M.; Ismail, G.A.; El-Sheekh, M.M. Potential assessment of some micro- and macroalgal species for bioethanol and biodiesel production. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2024, 46, 7683–7699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed, W.; Cabrol, A.; Salma, A.; Amrane, A.; Benoit, M.; Pierre, R.; Djelal, H. Green Macroalgae Hydrolysate for Biofuel Production: Potential of Ulva rigida. Appl. Microbiol. 2024, 4, 563–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allouache, A.; Majda, A.; Toudert, A.Z.; Amrane, A.; Ballesteros, M. Cellulosic bioethanol production from Ulva lactuca macroalgae. Cellul. Chem. Technol. 2021, 55, 629–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruangrit, K.; Chaipoot, S.; Phongphisutthinant, R.; Kamopas, W.; Jeerapan, I.; Pekkoh, J.; Srinuanpan, S. Environmental-friendly pretreatment and process optimization of macroalgal biomass for effective ethanol production as an alternative fuel using Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2021, 31, 101919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz-Jensen, N.; Thygesen, A.; Leipold, F.; Thomsen, S.T.; Roslander, C.; Lilholt, H.; Bjerre, A.B. Pretreatment of the macroalgae Chaetomorpha linum for the production of bioethanol—Comparison of five pretreatment technologies. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 140, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantino, A.; Rodrigues, B.; Leon, R.; Barros, R.; Raposo, S. Alternative chemo-enzymatic hydrolysis strategy applied to different microalgae species for bioethanol production. Algal Res. 2021, 56, 102329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokrkar, H.; Zamani, M.; Ebrahimi, S. Exploring strategies for the use of mixed microalgae in cellulase production and its application for bioethanol production. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefin. 2022, 16, 816–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seon, G.; Kim, H.S.; Cho JMKim, M.; Park, W.K.; Chang, Y.K. Effect of post-treatment process of microalgal hydrolysate on bioethanol production. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 16698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahorsu, R.; Medina, F.; Constantí, M. Significance and Challenges of Biomass as a Suitable Feedstock for Bioenergy and Biochemical Production: A Review. Energies 2018, 11, 3366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Sankaran, R.; Chew, K.W.; Tan, C.H.; Krishnamoorthy, R.; Chu, D.-T.; Show, P.-L. Waste to bioenergy: A review on the recent conversion technologies. BMC Energy 2019, 1, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekirogullari, M.; Figueroa-Torres, G.M.; Pittman, J.K.; Theodoropoulos, C. Models of microalgal cultivation for added-value products—A review. Biotechnol. Adv. 2020, 44, 107609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melendez, J.R.; Mátyás, B.; Hena, S.; Lowy, D.A.; El Salous, A. Perspectives in the production of bioethanol: A review of sustainable methods, technologies, and bioprocesses. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 160, 112260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maliha, A.; Abu-Hijleh, B. A review on the current status and post-pandemic prospects of third-generation biofuels. Energy Syst. 2023, 14, 1185–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laizu, S.; Hassan, L.; Ahmad, I. Open and closed photobioreactors for microalgal cultivation and wastewater treatment. In Nature-Based Technologies for Wastewater Treatment and Bioenergy Production; IWA Publish: London, UK, 2025; p. 121. [Google Scholar]

- Makaveckas, T.; Šimonėlienė, A.; Šipailaitė-Ramoškienė, V. Lignin Valorization from Lignocellulosic Biomass: Extraction, Depolymerization, and Applications in the Circular Bioeconomy. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandelwal, A.; Chhabra, M.; Lens, P.N. Integration of third generation biofuels with bio-electrochemical systems: Current status and future perspective. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1081108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio, E.; Rodríguez-Jasso, R.M.; Pinales-Márquez, C.D.; Loredo-Treviño, A.; Robledo-Olivo, A.; Aguilar, C.N.; Kostas, E.T.; Ruiz, H.A. High-pressure technology for Sargassum spp biomass pretreatment and fractionation in the third generation of bioethanol production. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 329, 124935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Y.; Manro, B.; Thakur, P.; Khera, A.; Dey, P.; Gupta, D.; Khajuria, A.; Jaiswal, P.K.; Barnwal, R.P.; Singh, G. Nanotechnology as a vital science in accelerating biofuel production, a boon or bane. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefin. 2023, 17, 616–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melendez, J.; Velasquez-Rivera, J.; El Salous, A.; Peñalver, A. Management for the production of 2G biofuels: Review of the technological and economic scenario. Rev. Venez. Gerenc. 2021, 26, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, C.; Scapini, T.; Rempel, A.; Abaide, E.R.; Camargo, A.F.; Nazari, M.T.; Tadioto, V.; Bonatto, C.; Tres, M.V.; Zabot, G.L.; et al. Challenges and opportunities for third-generation ethanol production: A critical review. Eng. Microbiol. 2022, 3, 100056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Gaur, A.; Soni, P.; Jain, R.; Pant, G.; Kumar, D.; Kumar, G.; Shamshuddin, S.; Mubarak, N.M.; Dehghani, M.H.; et al. A review of biofuels and bioenergy production as a sustainable alternative: Opportunities, challenges and future perspectives. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 2025, 23, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, H.S.; Swilam, M.M.; Hamza, Z.S.; Abdulqawi, A.R.; Kumar, Q.; Hamed, S.M. Harnessing seaweed biomass for sustainable bioethanol production and carbon sequestration: Technological advances and future prospects. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2025, 32, 24528–24553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thevarajah, B.; Nimarshana, P.H.V.; Chang, J.S.; Ariyadasa, T.U. Cost-effective large-scale production of Chlorella vulgaris-based biodiesel and bioethanol: A comparative assessment. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2026, 179, 106395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Element | Description |

|---|---|

| P (Population/Object of Study) | Industrial or experimental processes to produce third-generation bioethanol from micro-algal or macroalgal biomass. |

| I (Intervention) | Application of hydrolysis, fermentation, or biochemical conversion technologies for bioethanol production. |

| C (Comparator) | Alternative methods or variations within the same process (enzymatic vs. chemical, microalgae vs. macroalgae). |

| O (Outcome) | Bioethanol yield (g∙L−1, MJ∙kg−1), energy efficiency, GHG reduction, economic feasibility, and industrial scalability. |

| Included Study Designs | Experimental trials, laboratory studies, and simulation studies. |

| Languages | English and Spanish |

| Period | 2019–2025 |

| Search String |

|---|

| (“third-generation” OR “3G”) AND (bioethanol OR “bio-ethanol”) AND (alga* OR microalga* OR macroalga* OR seaweed*) AND (pretreat* OR pre-treat* OR hydrol* OR saccharif* OR ferment* OR “enzymatic hydrolysis” OR “acid hydrolysis” OR “simultaneous saccharification and fermentation” OR “hydrothermal” OR “hydrotropic”) AND (“yield OR productivity” OR “life cycle” OR scale*). |

| Feed Stock | Carbohydrate/Sugar Content | Hydrolysis Process | Ethanol Yield | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Macroalgae | ||||

| Ulva linza | 111.91 mg/g dry biomass | 3% acid treatment | 0.12 g ethanol/g sugar | [102] |

| Ulva rigida | 349.0 mg/g dry biomass | Enzymatic process: Amyloglucosidase and amylase enzymes | 0.44 g ethanol/g sugar | [103] |

| Ulva lactuca | 164.7 mg/g dry biomass | Thermal acid treatment followed by cellulase enzyme hydrolysis | 0.41 g ethanol/g sugar | [104] |

| Ulva intestinalis | 96.9 mg/g dry biomass | Steam explosion with cellulase enzyme hydrolysis | 0.117 g ethanol/g sugar | [105] |

| Chaetomorpha linum | 740 mg/g dry biomass | Wet oxidation method followed by cellulase hydrolysis | 0.44 g ethanol/g glucan | [106] |

| Microalgae | ||||

| Chlorella marina | 198.38 mg/g dry biomass | 3% acid treatment | 0.232 g ethanol/g sugar | [102] |

| Arthrospira platensis | 165.11 mg/g dry biomass | 3% acid treatment | 0.455 g ethanol/g sugar | [102] |

| Chlorella sorokiniana | 622 mg/g dry biomass | H2SO4, amyloglucosidase, α-amylase | 0.46 g ethanol/g sugar | [107] |

| Tetraselmis sp. | 866 mg/g dry biomass | H2SO4, amyloglucosidase, α-amylase | 0.42 g ethanol/g sugar | [107] |

| Skeletonema sp. | 930 mg/g dry biomass | H2SO4, amyloglucosidase, α-amylase | 0.43 g ethanol/g sugar | [107] |

| Mixed culture * | 119.2 mg/g dry biomass | Trichoderma reesei and Aspergillus niger are used for enzymatic hydrolysis | 0.46 g ethanol/g sugar | [108] |

| Chlorella sp. ABC−001 | 400 mg/g dry biomass | H2SO4 hydrolysis | 0.43 g ethanol/g sugar | [109] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Melendez, J.R.; Lowy, D.A.; Hena, S.; Gutierrez, L. Advances in Third-Generation Bioethanol Production, Industrial Infrastructure and Efficient Technologies in Sustainable Processes with Algae Biomass: Systematic Review. Fermentation 2026, 12, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation12010002

Melendez JR, Lowy DA, Hena S, Gutierrez L. Advances in Third-Generation Bioethanol Production, Industrial Infrastructure and Efficient Technologies in Sustainable Processes with Algae Biomass: Systematic Review. Fermentation. 2026; 12(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation12010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleMelendez, Jesus R., Daniel A. Lowy, Sufia Hena, and Leonardo Gutierrez. 2026. "Advances in Third-Generation Bioethanol Production, Industrial Infrastructure and Efficient Technologies in Sustainable Processes with Algae Biomass: Systematic Review" Fermentation 12, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation12010002

APA StyleMelendez, J. R., Lowy, D. A., Hena, S., & Gutierrez, L. (2026). Advances in Third-Generation Bioethanol Production, Industrial Infrastructure and Efficient Technologies in Sustainable Processes with Algae Biomass: Systematic Review. Fermentation, 12(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation12010002