Enhanced Cultivation of Actinomycetota Strains from Millipedes (Diplopoda) Using a Helper Strain-Assisted Method

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Candidates for Helper Strains

2.2. Selection of Type Strains

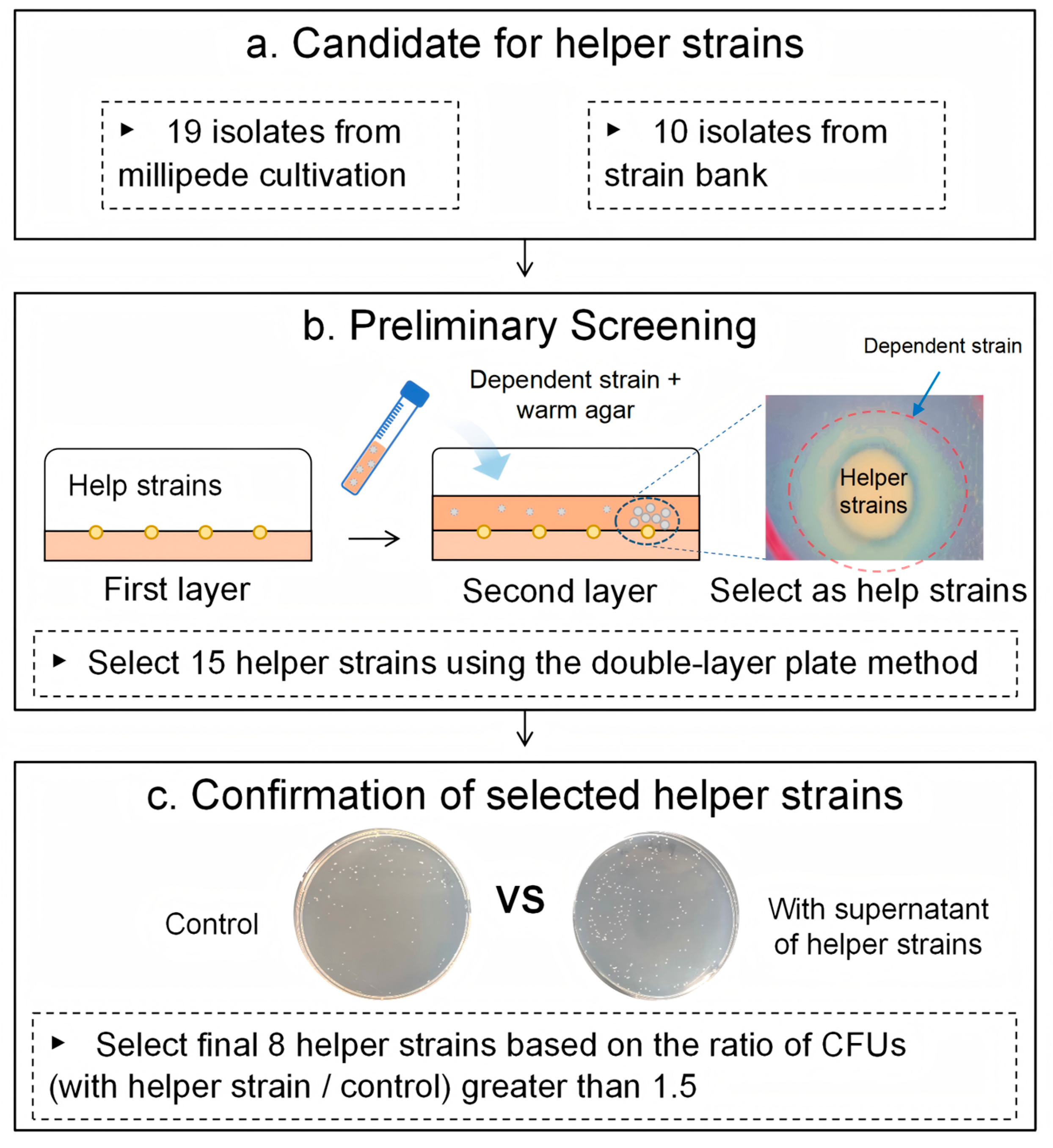

2.3. Preliminary Screening for Helper Strains Using a Double-Layer Plate Method

2.4. Confirmation of Growth-Promoting Effects Using Helper Strain Supernatants

2.5. Application of Helper Strain Supernatants for the Cultivation of Millipede-Associated Bacteria

2.6. 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing and Phylogenetic Identification

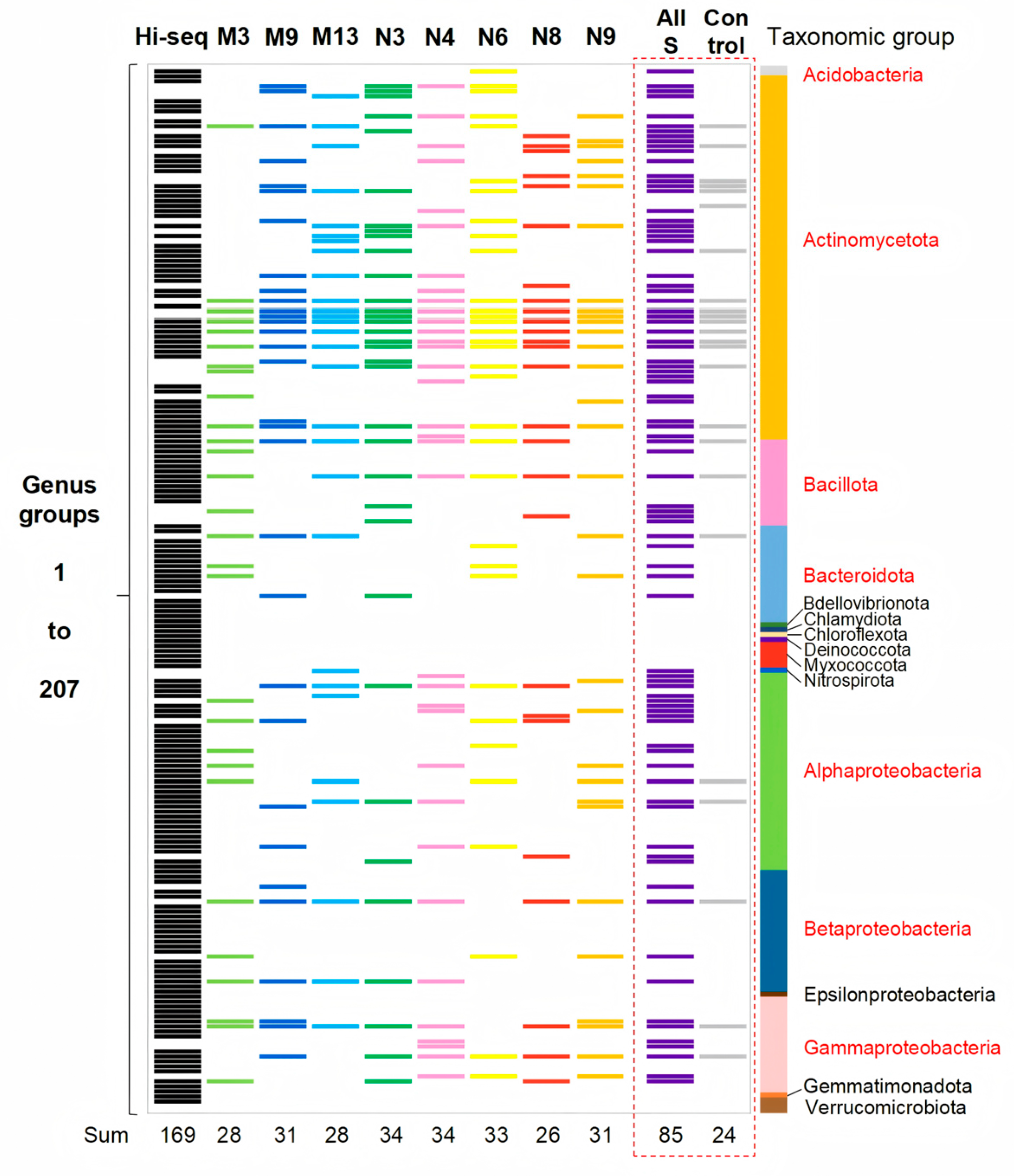

2.7. Comparison of Microbial Diversity via Illumina HiSeq Sequencing

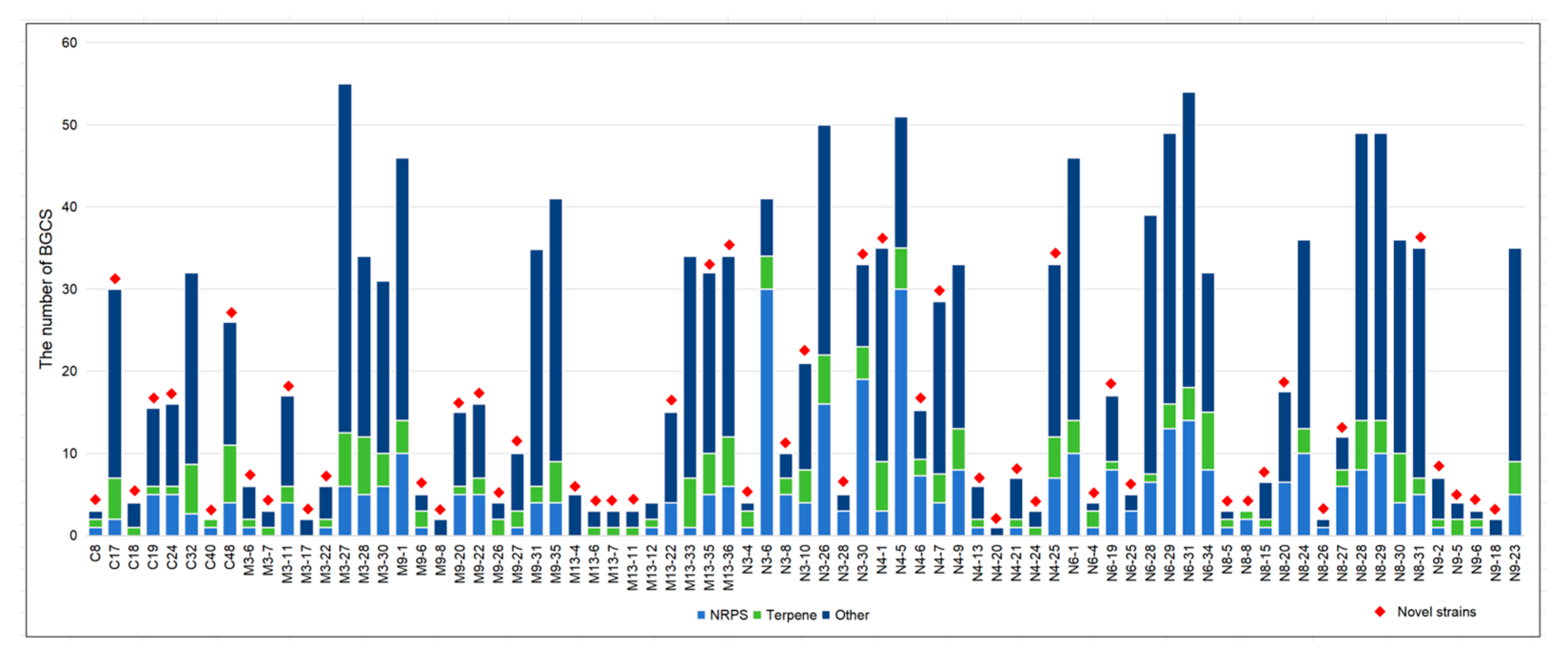

2.8. Prediction of BGCs Profiles by PSMPA

2.9. Screening for Antibacterial Activity

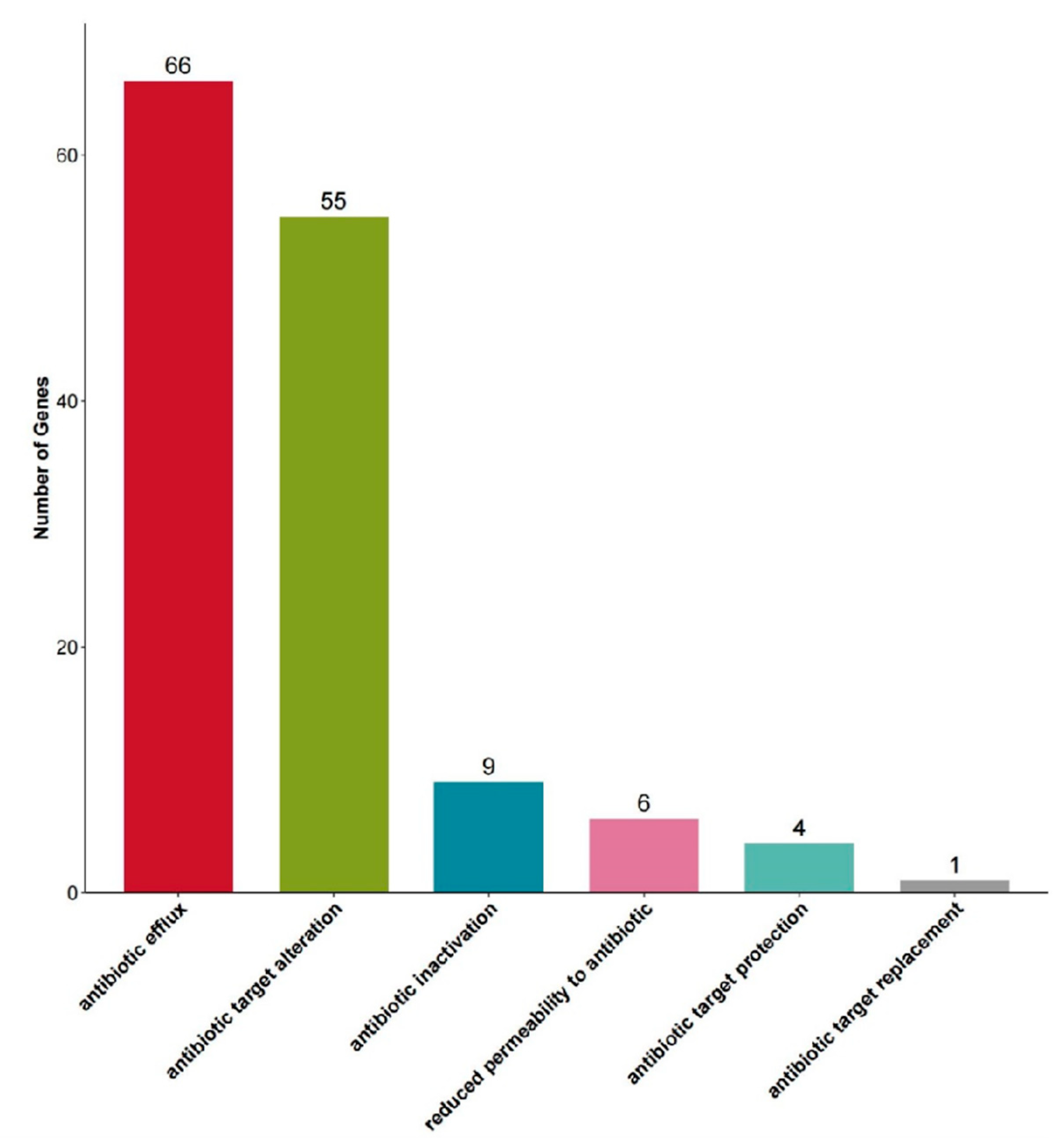

2.10. Genomic Analysis of Strain N8-31

3. Results

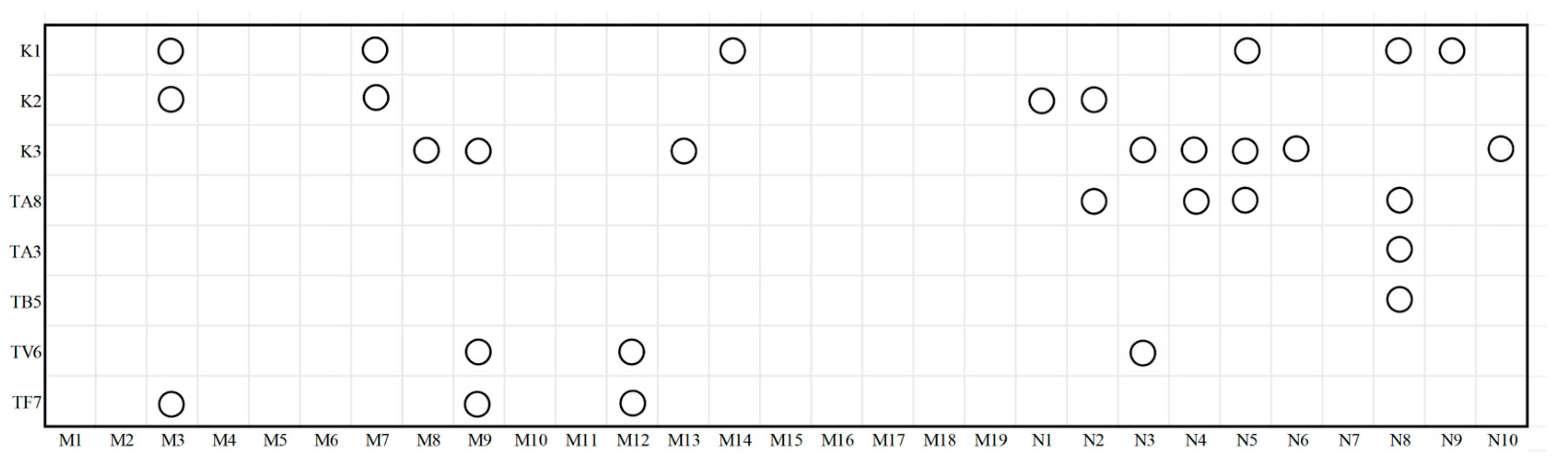

3.1. Preliminary Screening of Helper Strain Candidates

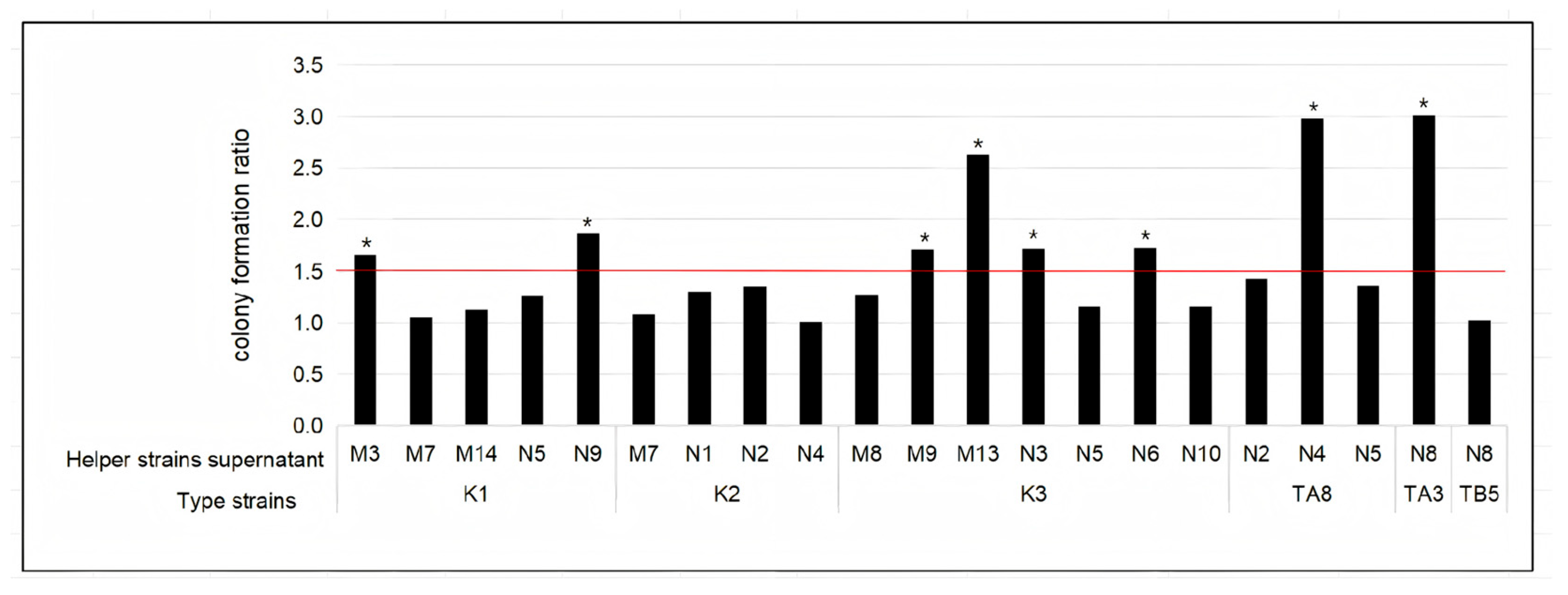

3.2. Confirmation of Growth Promoting of Selected Helper Strains

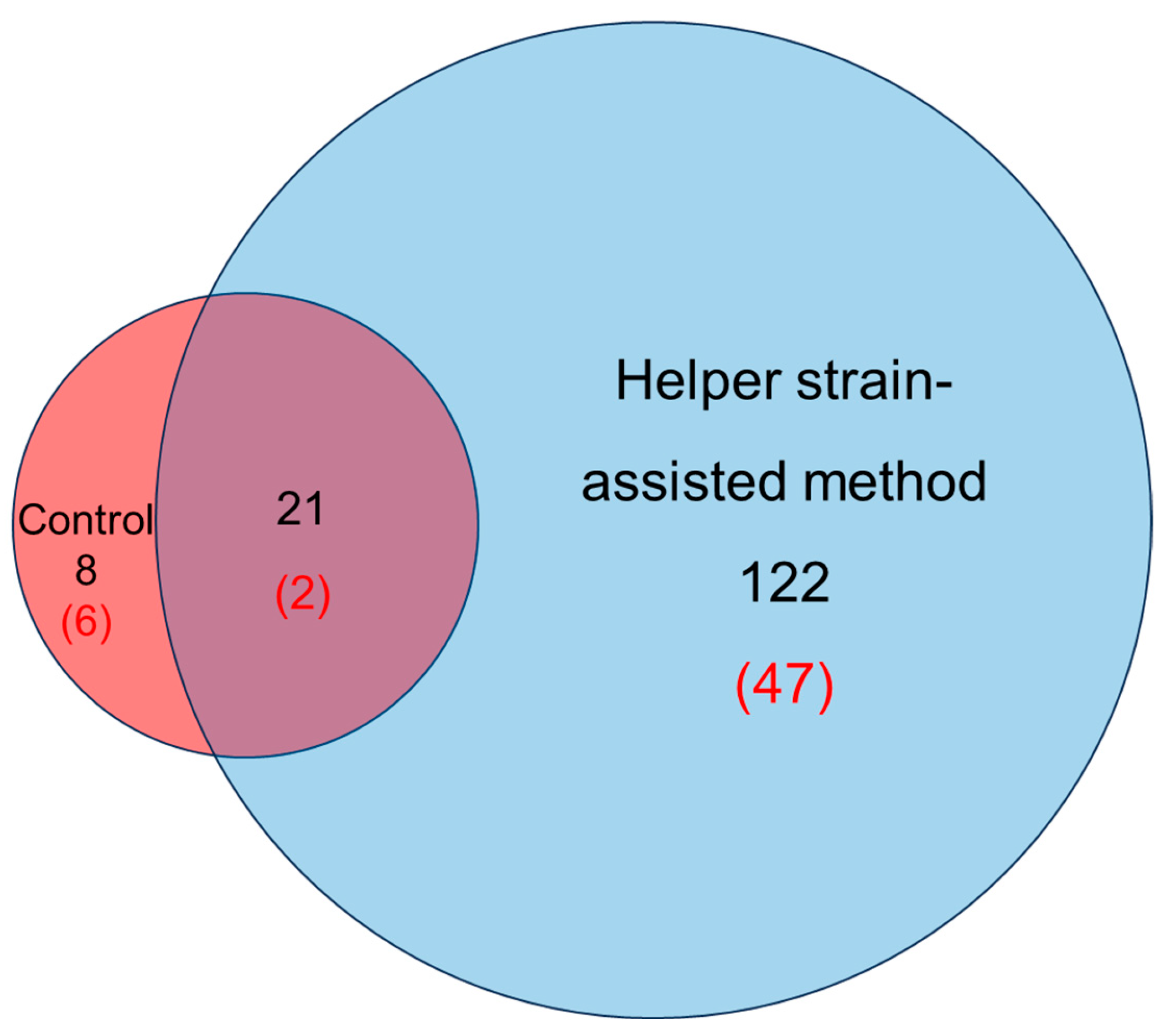

3.3. Enhanced Cultivation of Diverse Actinomycetota Strains Using Helper Strain Supernatants

3.4. Antimicrobial Activity Screening in Selected Actinomycetota Strains

3.5. Genomic Analysis of a Putative Novel Species (N8-31) Reveals High Biosynthetic Potential

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nweze, J.E.; Schweichhart, J.S.; Angel, R. Viral communities in millipede guts: Insights into the diversity and potential role in modulating the microbiome. Environ. Microbiol. 2024, 26, e16586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimvichai, P.; Jumpajan, W.; Buaboon, P.; Sutthisa, W.; Nantarat, N.; Backeljau, T. GC-MS analysis and antimicrobial properties of defensive secretions from the millipede Coxobolellus saratani (Diplopoda: Spirobolida: Pseudospirobolellidae). J. Chem. Ecol. 2025, 51, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srisonchai, R.; Enghoff, H.; Likhitrakarn, N.; Panha, S.; Sutcharit, C. Molecular and morphological data uncover a striking new genus of dragon millipedes in Thailand, with alternately long and short legs (Diplopoda, Polydesmida, Paradoxosomatidae). Invertebr. Syst. 2025, 39, IS25007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.Q.; Zhang, A.; Wang, H.; Niu, L.; Wang, Q.X.; Zhu, L.L.; Li, Y.Z.; Wu, C. Discovery and biosynthesis of glycosylated cycloheximide from a millipede-associated actinomycete. J. Nat. Prod. 2023, 86, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glukhova, A.A.; Karabanova, A.A.; Yakushev, A.V.; Semenyuk, I.I.; Boykova, Y.V.; Malkina, N.D.; Efimenko, T.A.; Ivankova, T.D.; Terekhova, L.P.; Efremenkova, O.V. Antibiotic activity of actinobacteria from the digestive tract of millipede Nedyopus dawydoffiae (Diplopoda). Antibiotics 2018, 7, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oren, A.; Garrity, G.M. Valid publication of the names of forty-two phyla of prokaryotes. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2021, 71, 005056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramani, R.; Aalbersberg, W. Marine actinomycetes: An ongoing source of novel bioactive metabolites. Microbiol. Res. 2012, 167, 571–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y. The principles and applications of high-throughput sequencing technologies. Dev. Reprod. 2023, 27, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, D.; Seo, E.Y.; Epstein, S.S.; Joung, Y.; Han, J.; Parfenova, V.V.; Belykh, O.I.; Gladkikh, A.S.; Ahn, T.S. Application of a new cultivation technology, I-tip, for studying microbial diversity in freshwater sponges of Lake Baikal, Russia. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2014, 90, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, D.; Cahoon, N.; Trakhtenberg, E.M.; Pham, L.; Mehta, A.; Belanger, A.; Kanigan, T.; Lewis, K.; Epstein, S.S. Use of ichip for high-throughput in situ cultivation of “uncultivable” microbial species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 2445–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Owen, J.S.; Seo, E.Y.; Jung, D.; He, S. Microbial interaction is among the key factors for isolation of previous uncultured microbes. J. Microbiol. 2023, 61, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, A.; Archer, A.M.; Biggs, M.B.; Papin, J.A. Growth-altering microbial interactions are responsive to chemical context. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0164919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, M.Z.; Subin Sasidharan, R.; Alghamdi, H.A.; Dang, H. Understanding interaction patterns within deep-sea microbial communities and their potential applications. Mar. Drugs. 2022, 20, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, S.; Li, N.; Habib, S.; Zheng, P.; Li, Y.; Liang, Y.; Qu, Y. Biological characteristics and whole-genome analysis of a porcine E. coli phage. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kropinski, A.M.; Mazzocco, A.; Waddell, T.E.; Lingohr, E.; Johnson, R.P. Enumeration of bacteriophages by double agar overlay plaque assay. Methods Mol. Biol. 2009, 501, 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, D.J. 16S/23S rRNA sequencing. In Nucleic Acid Techniques in Bacterial Systematics; Stackebrandt, E., Goodfellow, M., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; John Wiley and Sons: Chichester, UK, 1991; pp. 115–175. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, B.; Zhou, Z.-Y.; Lai, C.; Du, A.-Q.; Hu, G.-A.; Yu, W.; Yu, Y.-L.; Chen, J.-W.; Zhang, H.; Wu, Q.; et al. Predicting the secondary metabolic potential of microbiomes from marker genes using PSMPA. Preprint 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglin, R.C.; Stevens, M.J.; Meile, L.; Lacroix, C.; Meile, L. High-throughput screening assays for antibacterial and antifungal activities of Lactobacillus species. J. Microbiol. Methods 2015, 114, 26–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, A.W.; Kirby, W.M.; Sherris, J.C.; Turck, M. Antibiotic susceptibility testing by a standardized single disk method. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1966, 45, 493–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saar, M.; Wawrzyk, A.; Pastuszak-Lewandoska, D.; Bielec, F. Cefiderocol antimicrobial susceptibility testing by disk diffusion: Influence of agar media and inhibition zone morphology in K. pneumoniae metallo-β-lactamase. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Oh, H.S.; Park, S.C.; Chun, J. Towards a taxonomic coherence between average nucleotide identity and 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity for species demarcation of prokaryotes. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2014, 64, 346–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArthur, A.G.; Waglechner, N.; Nizam, F.; Yan, A.; Azad, M.A.; Baylay, A.J.; Bhullar, K.; Canova, M.J.; De Pascale, G.; Ejim, L.; et al. The comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 3348–3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blin, K.; Szenei, J.; Vader, L. Using antiSMASH. Methods Enzymol. 2025, 717, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stewart, E.J. Growing unculturable bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 2012, 194, 4151–4160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watve, M.; Shejval, V.; Sonawane, C.; Rahalkar, M.; Matapurkar, A.; Shouche, Y.; Patole, M.; Phadnis, N.; Champhenkar, A.; Damle, K.; et al. The ‘K’ selected oligophilic bacteria: A key to uncultured diversity? Curr. Sci. 2000, 78, 1535–1542. [Google Scholar]

- Kapinusova, G.; Lopez Marin, M.A.; Uhlik, O. Reaching unreachables: Obstacles and successes of microbial cultivation and their reasons. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1089630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriu, T.; Lotton, C.; Bénard-Capelle, J.; Misevic, D.; Brown, S.P.; Lindner, A.B.; Taddei, F. Genetic information transfer promotes cooperation in bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 11103–11108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, D.; Machida, K.; Nakao, Y.; Kindaichi, T.; Ohashi, A.; Aoi, Y. Triggering growth via growth initiation factors in nature: A putative mechanism for in situ cultivation of previously uncultivated microorganisms. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 537194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Wang, G.; Li, Y.; Gan, M. The secondary metabolites from genus Kitasatospora: A promising source for drug discovery. Chem. Biodivers. 2024, 21, e202401473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, D.; Seo, E.Y.; Owen, J.S.; Aoi, Y.; Yong, S.; Lavrentyeva, E.V.; Ahn, T.S. Application of the filter plate microbial trap (FPMT), for cultivating thermophilic bacteria from thermal springs in Barguzin area, eastern Baikal, Russia. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2018, 82, 1624–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, B.A.; Seeber, J.; Rief, A.; Meyer, E.; Insam, H. Bacterial community composition of the gut microbiota of Cylindroiulus fulviceps (Diplopoda) as revealed by molecular fingerprinting and cloning. Folia Microbiol. 2010, 55, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilić, B.; Unković, N.; Ćirić, A.; Glamočlija, J.; Ljaljević Grbić, M.; Raspotnig, G.; Bodner, M.; Vukojević, J.; Makarov, S. Phenol-based millipede defence: Antimicrobial activity of secretions from the Balkan endemic millipede Apfelbeckia insculpta (L. Koch, 1867) (Diplopoda: Callipodida). Naturwissenschaften 2019, 106, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura-Ramírez, P.J.; de Godoy, P.M.; Avino, I.N.; Silva Junior, P.I. Encrypted antimicrobial peptides from proteins present in the plasma of the millipede Rhinocricus sp. J. Proteom. 2021, 242, 104239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anavadiya, B.; Chouhan, S.; Saraf, M.; Goswami, D. Exploring Endophytic Actinomycetes: A rich reservoir of diverse antimicrobial compounds for combatting global antimicrobial resistance. Microbe 2024, 4, 100110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mast, Y.; Stegmann, E. Actinomycetes: The antibiotics producers. Antibiotics 2019, 8, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Isolate Number | Closest Species | Similarity | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M3-11 | Mycobacterium grossiae | 98.29 | + | ++ | − | − |

| M3-27 | Streptomyces corynorhini | 98.00 | + | + | − | − |

| M3-28 | Streptomyces glauciniger | 99.10 | ++ | ++ | − | − |

| M13-7 | Homoserinibacter gongjuensis | 97.89 | − | + | − | − |

| M13-36 | Streptomyces sodiiphilus | 97.24 | + | + | − | − |

| N3-6 | Aldersonia kunmingensis | 100.00 | + | − | − | − |

| N4-5 | Dactylosporangium tropicum | 99.43 | ++ | +++ | − | + |

| N4-7 | Kitasatospora cheerisanensis | 99.01 | − | + | − | − |

| N4-25 | Streptomyces corynorhini | 100.00 | ++ | + | − | − |

| N8-28 | Streptomyces alboniger | 98.79 | + | + | − | − |

| N8-31 | Streptomyces cinnabarigriseus | 98.07 | +++ | ++ | − | − |

| N9-6 | Cellulomonas pakistanensis | 97.55 | ++ | +++ | − | − |

| N9-23 | Streptomyces cinnabarigriseus | 98.71 | ++ | ++ | − | − |

| M9-35 | Streptomyces setonii | 99.84 | + | + | − | − |

| Region | Most Similar Known Species | Similarity (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Region 1 | Other | 100 |

| Region 2 | NRP | 7 |

| Region 3 | ||

| Region 4 | NRP | 100 |

| Region 5 | Terpene | 100 |

| Region 6 | NRP: Cyclic depsipeptide | 57 |

| Region 7 | Other | 100 |

| Region 8 | NRP | 100 |

| Region 9 | Other | 88 |

| Region 10 | NRP | 100 |

| Region 11 | Polyketide | 100 |

| Region 12 | NRP: Cyclic depsipeptide | 13 |

| Region 13 | NRP + Polyketide | 4 |

| Region 14 | Polyketide | 23 |

| Region 15 | Other | 57 |

| Region 16 | Polyketide: Iterative type I polyketide | 10 |

| Region 17 | NRP + Polyketide | 12 |

| Region 18 | Terpene | 61 |

| Region 19 | Polyketide | 16 |

| Region 20 | ||

| Region 21 | NRP + Polyketide | 4 |

| Region 22 | NRP + Polyketide | 33 |

| Region 23 | Other | 35 |

| Region 24 | Terpene | 100 |

| Region 25 | Terpene | 100 |

| Region 26 | ||

| Region 27 | NRP | 7 |

| Region 28 | Other | 13 |

| Region 29 | RiPP | 21 |

| Region 30 | NRP | 10 |

| Region 31 | Polyketide | 83 |

| Region 32 | Polyketide + Saccharide: Hybrid/tailoring saccharide | 10 |

| Region 33 | NRP + Polyketide: Modular type I polyketide + Saccharide: Hybrid/tailoring saccharide | 13 |

| Region 34 | RiPP: Lanthipeptide | 85 |

| Region 35 | Other | 13 |

| Region 36 | ||

| Region 37 | Polyketide | 13 |

| Region 38 | Polyketide | 54 |

| Region 39 | Polyketide | 21 |

| Region 40 | Polyketide | 5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Shi, Y.; Seo, E.-Y.; Owen, J.S.; He, Z.; Shi, L.; Yan, C.; Lin, W.; Jung, D.; He, S. Enhanced Cultivation of Actinomycetota Strains from Millipedes (Diplopoda) Using a Helper Strain-Assisted Method. Fermentation 2026, 12, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation12010016

Shi Y, Seo E-Y, Owen JS, He Z, Shi L, Yan C, Lin W, Jung D, He S. Enhanced Cultivation of Actinomycetota Strains from Millipedes (Diplopoda) Using a Helper Strain-Assisted Method. Fermentation. 2026; 12(1):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation12010016

Chicago/Turabian StyleShi, Yingying, Eun-Young Seo, Jeffrey S. Owen, Zhaoyun He, Liufei Shi, Chang Yan, Wenhan Lin, Dawoon Jung, and Shan He. 2026. "Enhanced Cultivation of Actinomycetota Strains from Millipedes (Diplopoda) Using a Helper Strain-Assisted Method" Fermentation 12, no. 1: 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation12010016

APA StyleShi, Y., Seo, E.-Y., Owen, J. S., He, Z., Shi, L., Yan, C., Lin, W., Jung, D., & He, S. (2026). Enhanced Cultivation of Actinomycetota Strains from Millipedes (Diplopoda) Using a Helper Strain-Assisted Method. Fermentation, 12(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation12010016