Evaluation of Expression and Clinicopathological Relevance of Small Nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs) in Invasive Breast Cancer †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Tissue Experiment

2.1.1. Differentially Expressed Genes in the Screening

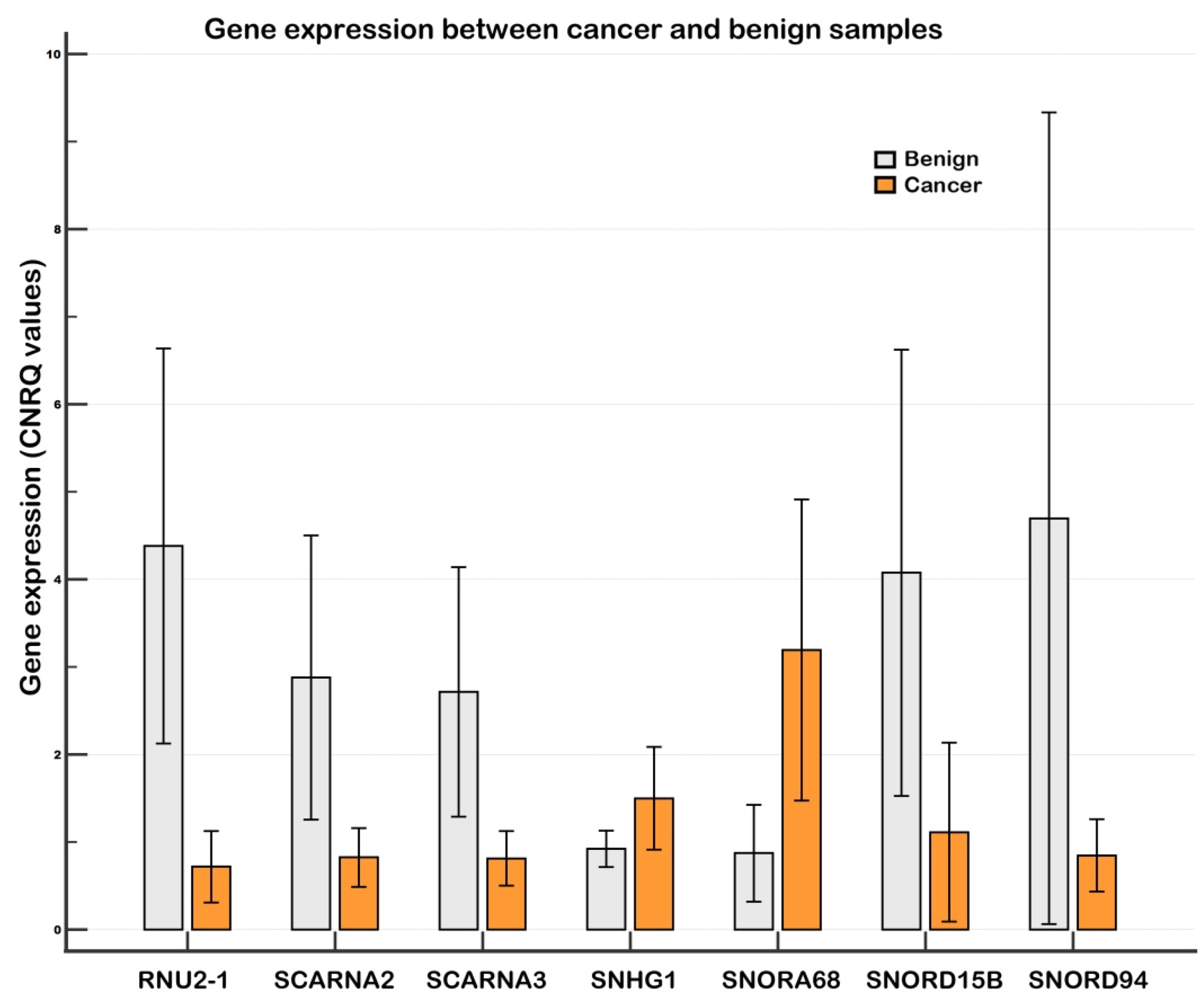

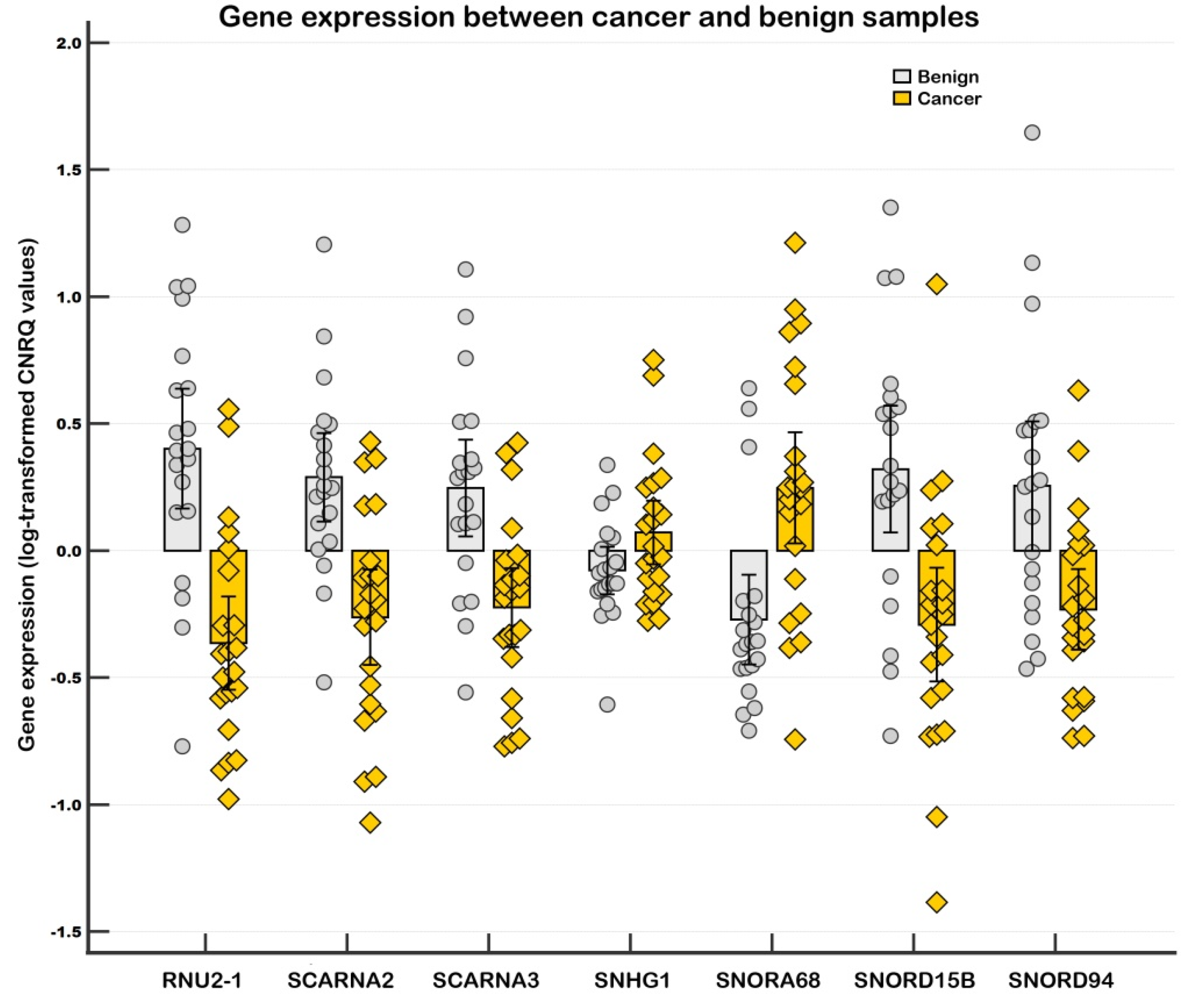

2.1.2. Differentially Expressed Genes in the Validation

2.1.3. Diagnostic Performance of the Investigated Genes

2.1.4. Associations with the Clinicopathological Characteristics

Stage and Grade

Multifocal Disease and Lymph Node Metastases (LNMs)

Estrogen (ER) and Progesterone (PR) Receptors, Ki-67 Proliferation Marker

2.1.5. Gene Expression in Tissues and Survival

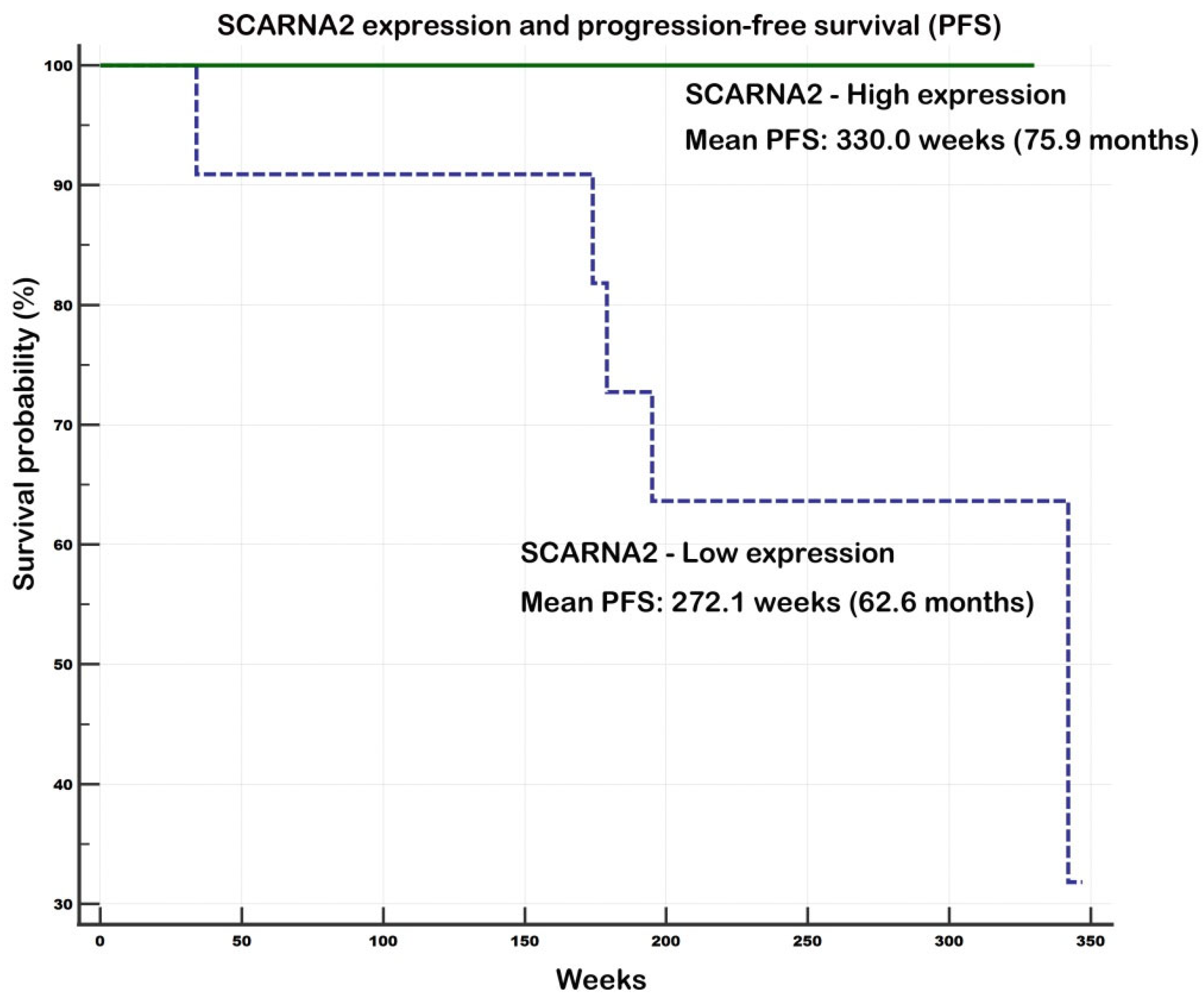

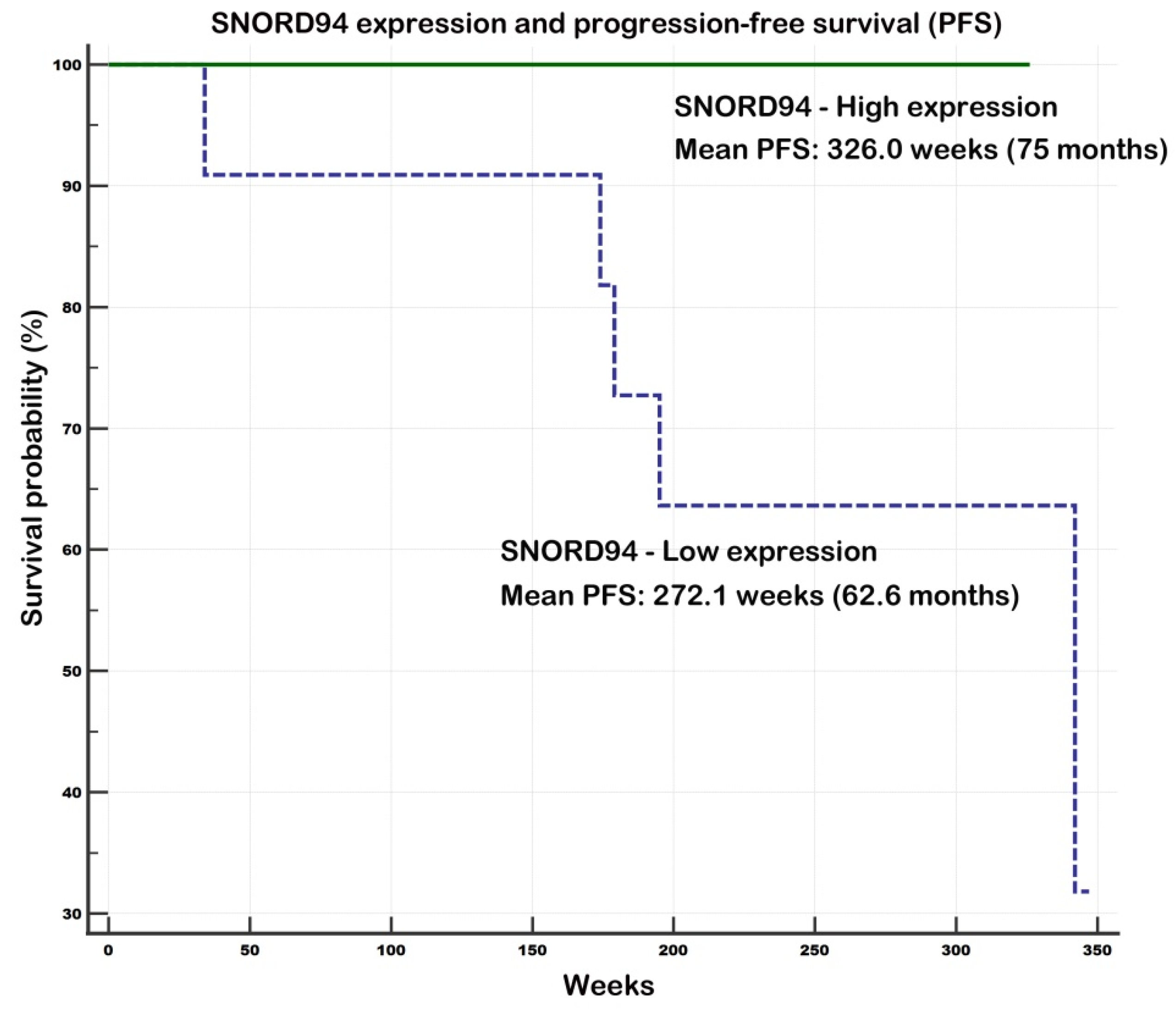

Evaluation of Prognostic Potential of SCARNA2 and SNORD94

2.2. External Validation

2.2.1. Differential Gene Expression Across Different Subtypes

2.2.2. Associations of Gene Expression and ER/PR/Her2 Status

2.2.3. Associations of Gene Expression and Survival

2.3. Expression of the Investigated Small Non-Coding RNAs in Plasma

3. Discussion

4. Limitations of the Study

5. Material and Methods

5.1. Patients and Samples

5.1.1. Part I—Tumor and Benign Tissues

5.1.2. Part II—Blood Plasma

5.2. Selection of the Investigated Genes

5.3. Total RNA Isolation, Reverse Transcription and qPCR

5.4. Statistical Analysis

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaquinto, A.N.; Sung, H.; Newman, L.A.; Freedman, R.A.; Smith, R.A.; Star, J.; Jemal, A.; Siegel, R.L. Breast cancer statistics 2024. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 477–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, J.S.; Mullins, M.; Cheang, M.C.; Leung, S.; Voduc, D.; Vickery, T.; Davies, S.R.; Fauron, C.; He, X.; Hu, Z.; et al. Supervised risk predictor of breast cancer based on intrinsic subtypes. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 1160–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastien, R.R.; Rodríguez-Lescure, Á.; Ebbert, M.T.W.; Prat, A.; Munárriz, B.; Rowe, L.; Miller, P.; Ruiz-Borrego, M.; Anderson, D.; Lyons, B.; et al. PAM50 breast cancer subtyping by RT-qPCR and concordance with standard clinical molecular markers. BMC Med. Genom. 2012, 5, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Záveský, L.; Jandáková, E.; Weinberger, V.; Minář, L.; Hanzíková, V.; Dušková, D.; Faridová, A.; Turyna, R.; Slanař, O.; Hořínek, A.; et al. Small non-coding RNA profiling in breast cancer: Plasma U6 snRNA, miR-451a and miR-548b-5p as novel diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2022, 49, 1955–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Záveský, L.; Jandáková, E.; Weinberger, V.; Minář, L.; Kohoutová, M.; Slanař, O. Human endogenous retroviruses in breast cancer: Altered expression pattern implicates divergent roles in carcinogenesis. Oncology 2024, 102, 858–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Záveský, L.; Jandáková, E.; Weinberger, V.; Minář, L.; Kohoutová, M.; Slanař, O. Long non-coding RNAs PTENP1, GNG12-AS1, MAGI2-AS3 and MEG3 as tumor suppressors in breast cancer and their associations with clinicopathological parameters. Cancer Biomark. 2024, 40, 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Záveský, L.; Jandáková, E.; Weinberger, V.; Minář, L.; Kohoutová, M.; Tefr Faridová, A.; Slanař, O. The overexpressed microRNAs miRs-182, 155, 493, 454, and U6 snRNA and underexpressed let-7c, miR-328, and miR-451a as potential biomarkers in invasive breast cancer and their clinicopathological significance. Oncology 2025, 103, 112–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Záveský, L.; Jandáková, E.; Weinberger, V.; Minář, L.; Turyna, R.; Slanař, O. Variable roles of miRNA- and apoptosis-linked genes in invasive breast cancer: Expression patterns, clinicopathological associations, and prognostic significance. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2025, 52, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahramy, A.; Zafari, N.; Rajabi, F.; Aghakhani, A.; Jayedi, A.; Khaboushan, A.S.; Zolbin, M.M.; Yekaninejad, M.S. Prognostic and diagnostic values of non-coding RNAs as biomarkers for breast cancer: An umbrella review and pan-cancer analysis. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2023, 10, 1096524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Werf, J.; Chin, C.V.; Fleming, N.I. SnoRNA in Cancer Progression, Metastasis and Immunotherapy Response. Biology 2021, 10, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvorská, D.; Braný, D.; Ňachajová, M.; Halašová, E.; Danková, Z. Breast Cancer and the Other Non-Coding RNAs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dsouza, V.L.; Adiga, D.; Sriharikrishnaa, S.; Suresh, P.S.; Chatterjee, A.; Kabekkodu, S.P. Small nucleolar RNA and its potential role in breast cancer—A comprehensive review. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 2021, 1875, 188501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saadh, M.J.; Abd Hamid, J.; Malathi, H.; Kazmi, S.W.; Omar, T.M.; Sharma, A.; Kumar, M.R.; Aggarwal, T.; Sead, F.F. SNHG family lncRNAs: Key players in the breast cancer progression and immune cell’s modulation. Exp. Cell Res. 2025, 447, 114531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escuin, D.; Bell, O.; García-Valdecasas, B.; Clos, M.; Larrañaga, I.; López-Vilaró, L.; Mora, J.; Andrés, M.; Arqueros, C.; Barnadas, A. Small Non-Coding RNAs and Their Role in Locoregional Metastasis and Outcomes in Early-Stage Breast Cancer Patients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breast Cancer Gene-Expression Miner v5.2 (bc-GenExMiner v5.2). Available online: https://bcgenex.ico.unicancer.fr/ (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Jézéquel, P.; Campone, M.; Gouraud, W.; Charbonnel, C.; Leux, C.; Ricolleau, G.; Campion, L. bc-GenExMiner: An easy-to-use online platform for gene prognostic analyses in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2012, 131, 765–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jézéquel, P.; Gouraud, W.; Ben Azzouz, F.; Guérin-Charbonnel, C.; Juin, P.; Lasla, H.; Campone, M. bc-GenExMiner 4.5: New mining module computes breast cancer differential gene expression analyses. Database 2021, 2021, baab007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Lei, J.; Ou, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Tuo, X.; Zhang, B.; Shen, M. Mammography diagnosis of breast cancer screening through machine learning: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Exp. Med. 2023, 23, 2341–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriharikrishnaa, S.; Suresh, P.S.; Prasada, K.S. An Introduction to Fundamentals of Cancer Biology. In Optical Polarimetric Modalities for Biomedical Research; Biological and Medical Physics, Biomedical Engineering; Mazumder, N., Kistenev, Y.V., Borisova, E., Prasada, K.S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakal, T.C.; Dhabhai, B.; Pant, A.; Moar, K.; Chaudhary, K.; Yadav, V.; Ranga, V.; Sharma, N.K.; Kumar, A.; Maurya, P.K.; et al. Oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes: Functions and roles in cancers. MedComm 2024, 5, e582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otmani, K.; Rouas, R.; Lewalle, P. OncomiRs as noncoding RNAs having functions in cancer. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 913951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Venkatesh, D.; Kandasamy, T.; Ghosh, S.S. Epigenetic modulations in breast cancer: An emerging paradigm in therapeutic implications. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed.) 2024, 29, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, S.; Sarkar, S.; Ghosh, S.; Chowdhury, A.A. DNA methylation as an oncogenic driver in breast cancer: Therapeutic targeting via epigenetic reprogramming of DNA methyltransferases. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2025, 242, 117313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solaimani, M.; Hosseinzadeh, S.; Abasi, M. Non-coding RNAs, a double-edged sword in breast cancer prognosis. Cancer Cell Int. 2025, 25, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergstrand, S.; O’Brien, E.M.; Coucoravas, C.; Hrossova, D.; Peirasmaki, D.; Schmidli, S.; Dhanjal, S.; Pederiva, C.; Siggens, L.; Mortusewicz, O.; et al. Small Cajal body-associated RNA 2 (scaRNA2) regulates DNA repair pathway choice by inhibiting DNA-PK. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, L.; Tan, W.; Song, Q.; Pei, H.; Li, J. BRCA1 and Breast Cancer: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Strategies. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 813457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Shen, H.; Liu, T.; Cao, K.; Wan, Z.; Du, Z.; Wang, H.; Yu, Y.; Ma, S.; Lu, E.; et al. ATR-binding lncRNA ScaRNA2 promotes cancer resistance through facilitating efficient DNA end resection during homologous recombination repair. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 42, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logan, M.K.; Burke, M.F.; Hebert, M.D. Altered Dynamics of scaRNA2 and scaRNA9 in Response to Stress Correlates with Disrupted Nuclear Organization. Biol. Open 2018, 7, bio037101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronchetti, D.; Todoerti, K.; Tuana, G.; Agnelli, L.; Mosca, L.; Lionetti, M.; Fabris, S.; Colapietro, P.; Miozzo, M.; Ferrarini, M.; et al. The expression pattern of small nucleolar and small Cajal body-specific RNAs characterizes distinct molecular subtypes of multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer J. 2012, 2, e96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, S.; Ravan, M.; Karimi-Sani, I.; Aria, H.; Hasan-Abad, A.M.; Banasaz, B.; Atapour, A.; Sarab, G.A. Screening and identification of potential biomarkers for pancreatic cancer: An integrated bioinformatics analysis. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2023, 249, 154726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Chen, X.; Liu, X.; Xie, B.; Chen, J.; Qin, H.; Zhao, Y. Small Nucleolar RNA and C/D Box 15B Regulate the TRIM25/P53 Complex to promote the Development of Endometrial Cancer. J. Oncol. 2022, 2022, 7762708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.P.; Lu, W.Q.; Huang, Y.J.; He, J.Y.; Wang, Q.; Zheng, X.F.; Wang, Z.D. SNORD15B and SNORA5C: Novel Diagnostic and Prognostic Biomarkers for Colorectal Cancer. Biomed. Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 8260800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.W.; Zhang, P.K.; Xiong, Z.; Lan, Y.F.; Guo, H.; Wu, R.Y.; Li, C.Z.; Fan, H.Z.; Du, Y.; Zhu, X.X. Snord15b Maintains Stemness of Intestinal Stem Cells via Enhancement of Alternative Splicing of Btrc Short Isoform for Suppression of β-Catenin Ubiquitination. Adv. Sci. 2025, 30, e04485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, F.; Qu, H.; Lin, Q.; Yang, Y.; Ruan, X.; Zhang, B.; Liu, Y.; Yu, C.; Zhang, H.; Fang, X.; et al. Molecular biomarkers screened by next-generation RNA sequencing for non-sentinel lymph node status prediction in breast cancer patients with metastatic sentinel lymph nodes. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2015, 13, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, X.; Ding, S.; Yu, M.; Niu, L.; Xue, L.; Zhao, Y.; Xie, L.; Song, X.; Song, X. Small Nuclear RNAs (U1, U2, U5) in Tumor-Educated Platelets Are Downregulated and Act as Promising Biomarkers in Lung Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.; Feng, Y.Q.; Li, L.; Yao, J.; Zhou, M.R.; Zhao, P.; Huang, F.; Zeng, L.; Yuan, L. Long non-coding RNA SNHG1 promotes breast cancer progression by regulation of LMO4. Oncol. Rep. 2020, 43, 1503–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.K.; Yang, L.; Hou, L.; Tang, X.Y. LncRNA SNHG1 promotes tumor progression and cisplatin resistance through epigenetically silencing miR-381 in breast cancer. Bioengineered 2021, 12, 9239–9250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, G.S.; Yang, Y.P.; Liu, S.H.; Liu, H.T. Exosomal SNHG1 Promotes Breast Cancer Growth and Angiogenesis via Regulating miR-216b-5p/JAK2 Axis. Cancer Manag. Res. 2022, 14, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Wang, J.; Song, J.; Wu, Q.; Gong, Z.; Song, J.; Hou, L. Long noncoding RNA SNHG1 promotes breast cancer progression by regulating the miR-641/RRS1 axis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 3265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Gong, C.L.; Wu, Y.Y.; Xie, X.; Chen, Y.; Li, Z.; Shi, Q.; Liu, J.; Gao, N.; He, B.; et al. LncRNA SNHG1 facilitates colorectal cancer cells metastasis by recruiting HNRNPD protein to stabilize SERPINA3 mRNA. Cancer Lett. 2024, 604, 217217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielske, S.P.; Chen, W.; Ibrahim, K.G.; Cackowski, F.C. SNHG1 opposes quiescence and promotes docetaxel sensitivity in prostate cancer. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.Z.; Xu, H.F.; Lu, H.C.; Xu, W.Z.; Liu, H.F.; Wang, X.W.; Zhou, G.R.; Yang, X.J. LncRNA SNHG1 Facilitates Tumor Proliferation and Represses Apoptosis by Regulating PPARγ Ubiquitination in Bladder Cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 4740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.R.; Song, X.Y.; Jin, Z.N.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Li, S.; Jin, F.; Zheng, A. U2AF2-SNORA68 promotes triple-negative breast cancer stemness through the translocation of RPL23 from nucleoplasm to nucleolus and c-Myc expression. Breast Cancer Res. 2024, 26, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fu, M.; Zheng, Z.Y.; Feng, J.G.; Zhang, C.X. Small Nucleolar RNAs: Biological Functions and Diseases. MedComm 2025, 6, e70257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandesompele, J.; De Preter, K.; Pattyn, F.; Poppe, B.; Van Roy, N.; De Paepe, A.; Speleman, F. Accurate normalization of realtime quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 2002, 3, research0034.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellemans, J.; Mortier, G.; De Paepe, A.; Speleman, F.; Vandesompele, J. qBase relative quantification framework and software for management and automated analysis of real-time quantitative PCR data. Genome Biol. 2007, 8, R19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| I. Endogenous control normalization | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Downregulated expression | |||||

| Gene | p | Ratio | FD | 95% CI, Low (FD) | 95% CI, High (FD) |

| RNU2-1 | 0.00008 | 0.17 | −5.83 | −11.29 | −3.01 |

| SNORD15B | 0.00070 | 0.24 | −4.10 | −8.65 | −1.95 |

| SCARNA2 | 0.00021 | 0.28 | −3.57 | −6.34 | −2.01 |

| SNORD94 | 0.00261 | 0.33 | −3.06 | −5.90 | −1.59 |

| SCARNA3 | 0.00070 | 0.34 | −2.96 | −5.08 | −1.72 |

| Upregulated expression | |||||

| Gene | p | Ratio | FD | 95% CI, Low (FD) | 95% CI, High (FD) |

| SNORA68 | 0.00070 | 3.30 | 3.30 | 1.75 | 6.22 |

| SNHG1 | 0.14896 * | 1.41 | 1.41 | 0.99 | 2.01 |

| II. Global mean normalization | |||||

| Downregulated expression | |||||

| Gene | p | Ratio | FD | 95% CI, Low (FD) | 95% CI, High (FD) |

| RNU2-1 | 0.000002 | 0.22 | −4.48 | −7.05 | −2.85 |

| SNORD15B | 0.00013 | 0.32 | −3.15 | −5.27 | −1.89 |

| SCARNA2 | 0.00004 | 0.36 | −2.74 | −4.22 | −1.78 |

| SNORD94 | 0.00069 | 0.43 | −2.35 | −3.78 | −1.46 |

| SCARNA3 | 0.00001 | 0.44 | −2.27 | −3.13 | −1.65 |

| Upregulated expression | |||||

| Gene | p | Ratio | FD | 95% CI, Low (FD) | 95% CI, High (FD) |

| SNHG1 | 0.00008 | 1.83 | 1.83 | 1.42 | 2.36 |

| SNORA68 | 0.00014 | 4.29 | 4.29 | 2.25 | 8.19 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Záveský, L.; Jandáková, E.; Weinberger, V.; Minář, L.; Turyna, R.; Faridová, A.T.; Hanzíková, V.; Slanař, O. Evaluation of Expression and Clinicopathological Relevance of Small Nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs) in Invasive Breast Cancer. Non-Coding RNA 2025, 11, 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/ncrna11060076

Záveský L, Jandáková E, Weinberger V, Minář L, Turyna R, Faridová AT, Hanzíková V, Slanař O. Evaluation of Expression and Clinicopathological Relevance of Small Nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs) in Invasive Breast Cancer. Non-Coding RNA. 2025; 11(6):76. https://doi.org/10.3390/ncrna11060076

Chicago/Turabian StyleZáveský, Luděk, Eva Jandáková, Vít Weinberger, Luboš Minář, Radovan Turyna, Adéla Tefr Faridová, Veronika Hanzíková, and Ondřej Slanař. 2025. "Evaluation of Expression and Clinicopathological Relevance of Small Nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs) in Invasive Breast Cancer" Non-Coding RNA 11, no. 6: 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/ncrna11060076

APA StyleZáveský, L., Jandáková, E., Weinberger, V., Minář, L., Turyna, R., Faridová, A. T., Hanzíková, V., & Slanař, O. (2025). Evaluation of Expression and Clinicopathological Relevance of Small Nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs) in Invasive Breast Cancer. Non-Coding RNA, 11(6), 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/ncrna11060076