AuNP-Containing Hydrogels Based on Arabinogalactan and κ-Carrageenan with Antiradical Activity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Synthesis of Ar-Gal-Stabilized AuNPs

2.2. Structural Analysis of Au-Ar-Gal Nanocomposites

2.3. Assessment of Radical-Binding Capacity of Ar-GalAuNPs Composites by Chemiluminescent Method

2.4. Creation and Characterization of Structural, Mechanical and Rheological Properties of Hydrogels Based on Ar-Gal-Stabilized AuNPs and κCG

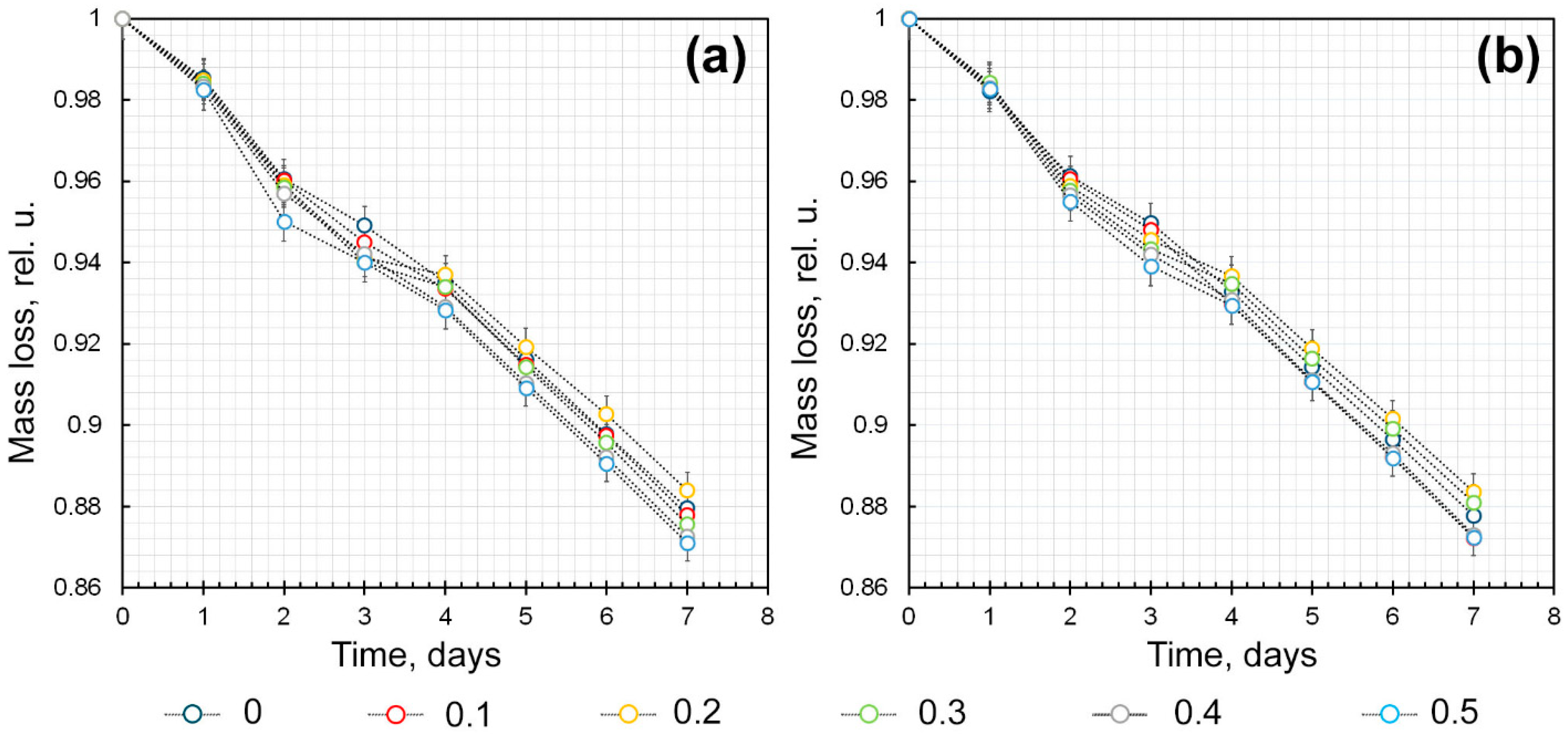

2.4.1. Assessment of Water-Holding Capacity of κCG-Ar-Gal-AuNPs Hydrogels

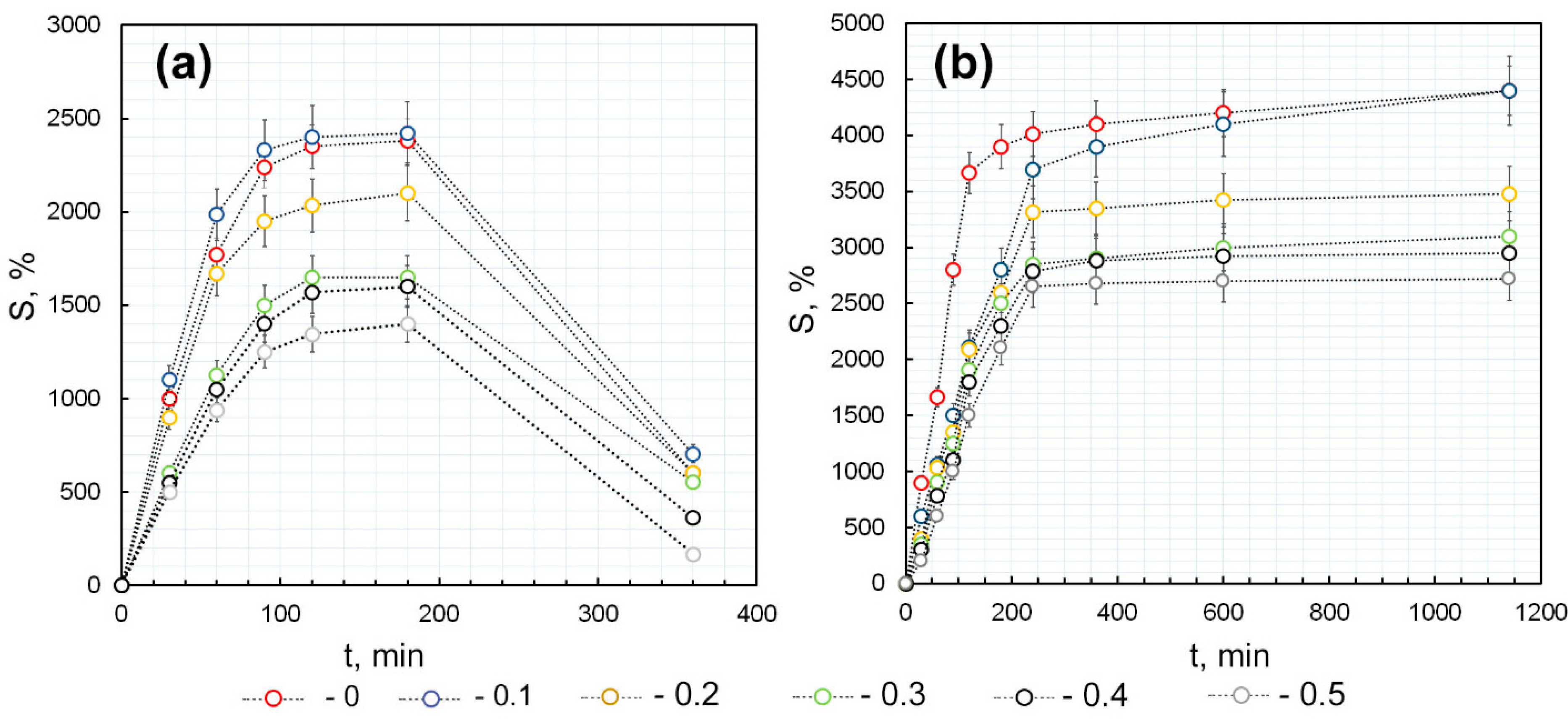

2.4.2. Assessment of the Swelling of κCG-Ar-Gal-AuNPs Hydrogels

2.4.3. Evaluation of the Dynamics of AuNPs Release from the κCG-Ar-Gal-AuNPs Hydrogel

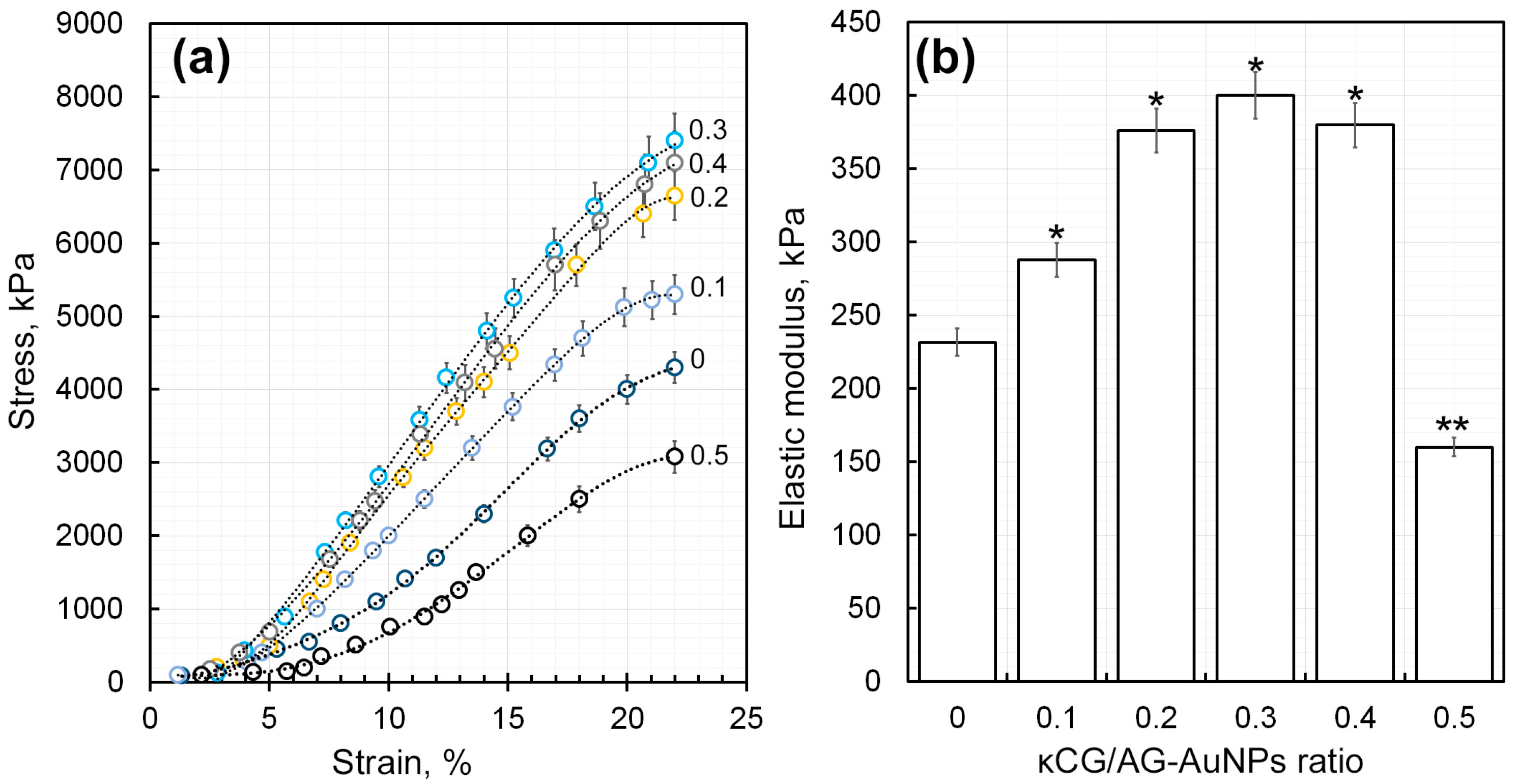

2.4.4. Determination of the Elasticity Modulus of κCG-Ar-Gal-AuNPs Hydrogels Crosslinked by Calcium Ions

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Methods

4.2.1. Transmission Electron Microscopy

4.2.2. Elemental Analysis

4.2.3. Dynamic Light Scattering

4.2.4. Optical Spectroscopy

4.2.5. FTIR-Spectroscopy

4.3. The General Method of Nanocomposites Synthesis

4.4. Assessment of Radical-Binding Ability of Gold Nanoparticles

4.4.1. Evaluation of Antiradical Activity Using the Radical-Generating System «Horseradish Peroxidase-Hydrogen Peroxide-Luminol»

4.4.2. Study of the Radical-Binding Ability of Composite Using the «ABAP-Luminol» Radical-Generating System

4.5. Preparation of Ar-Gal-AuNPs-κ-CG Hydrogels

4.6. Study of Water-Holding Capacity of Hydrogels

4.7. Study of AuNPs Release Dynamics from Hydrogels in Aqueous Medium

4.8. Investigation of Gel Swelling

4.9. Determination of the Elastic Modulus of Composite Hydrogels κ-CG-AG-AuNPs-Ca2+

4.10. Statistical Analyses

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tessaro, L.; Aquino, A.; Azevedo de Carvalho, A.P.; Conte-Junior, C.A. A systematic review on gold nanoparticles based-optical biosensors for Influenza virus detection. Sens. Actuators Rep. 2021, 3, 100060–100073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yafout, M.; Ousaid, A.; Khayati, Y.; El Otmani, I.S. Gold nanoparticles as a drug delivery system for standard chemotherapeutics: A new lead for targeted pharmacological cancer treatments. Sci. Afr. 2021, 11, e00685–e00696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Hirst, D.G.; O’Sullivan, J.M. Gold nanoparticles as novel agents for cancer therapy. Br. J. Radiol. 2012, 85, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia Calavia, P.; Bruce, G.; Perez-Garcia, L.; Russell, D.A. Photosensitiser-gold nanoparticle conjugates for photodynamic therapy of cancer. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2018, 17, 1534–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikhailova, E.O. Gold Nanoparticles: Biosynthesis and Potential of Biomedical Application. J. Funct. Biomater. 2021, 12, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dykman, L.A.; Khlebtsov, N.G. Gold Nanoparticles in Biology and Medicine: Recent Advances and Prospects. Acta Naturae 2011, 3, 34–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milan, J.; Niemczyk, K.; Kus-Liskiewicz, M. Treasure on the Earth—Gold Nanoparticles and Their Biomedical Applications. Materials 2022, 15, 3355–3375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koushki, K.; Keshavarz Shahbaz, S.; Keshavarz, M.; Bezsonov, E.E.; Sathyapalan, T.; Sahebkar, A. Gold Nanoparticles: Multifaceted Roles in the Management of Autoimmune Disorders. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Hakem, N.E.; Talaat, R.M.; Samaka, R.M.; Bassyouniy, I.N.; El-Shahat, M.; Alkawareek, M.Y.; Alkilany, A.M. Therapeutic outcomes and biodistribution of gold nanoparticles in collagen-induced arthritis animal model. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2022, 67, 102944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yang, Y.G.; Sun, T. Nanoparticle-Based Drug Delivery Systems for Induction of Tolerance and Treatment of Autoimmune Diseases. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 889291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darweesh, R.S.; Ayoub, N.M.; Nazzal, S. Gold nanoparticles and angiogenesis: Molecular mechanisms and biomedical applications. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, 14, 7643–7663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aili, M.; Zhou, K.; Zhan, J.; Zheng, H.; Luo, F. Anti-inflammatory role of gold nanoparticles in the prevention and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Mater. Chem. B 2023, 11, 8605–8621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujita, T.; Zysman, M.; Elgrabli, D.; Murayama, T.; Haruta, M.; Lanone, S.; Ishida, T.; Boczkowski, J. Anti-inflammatory effect of gold nanoparticles supported on metal oxides. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 23129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, V.; Patil, A.; Phatak, A.; Chandra, N. Free radicals, antioxidants and functional foods: Impact on human health. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2010, 4, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, M.; Abdolhosseini, M.; Zarrabi, A.; Johari, B. A review on application of Nano-structures and Nano-objects with high potential for managing different aspects of bone malignancies. Nano-Struct. Nano-Objects 2019, 19, 100348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaq, H.; Saira, F.; Yaqub, A.; Qureshi, R.; Mumtaz, M.; Saleemi, S. Interaction of gold nanoparticles with free radicals and their role in enhancing the scavenging activity of ascorbic acid. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2016, 161, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen-Thi, N.Y.; Thao, T.T.N.; Thao, P.T.B.; Nguyen, M.T.; Nhat, P.V. Effects of Gold Nanoparticles on the Antioxidant Power of Gallic Acid: A Computational Investigation Using a Cluster Model. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 38640–38652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinoshita, A.; Lima, L.; Guidelli, E.J.; Filho, O.B. Antioxidative activity of gold and platinum nanoparticles assessed through electron spin resonance. Eclética Química J. 2021, 46, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, K.; Nazir, S.; Li, B.; Khan, A.U.; Khan, Z.U.H.; Gong, P.Y.; Khan, S.U.; Ahmad, A. Nerium oleander leaves extract mediated synthesis of gold nanoparticles and its antioxidant activity. Mater. Lett. 2015, 156, 198–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabestarian, H.; Homayouni-Tabrizi, M.; Soltani, M.; Namvar, F.; Azizi, S.; Mohamad, R.; Shabestarian, H. Green Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles Using Sumac Aqueous Extract and Their Antioxidant Activity. Mater. Res. 2017, 20, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanezi, F.G.; Meireles, L.M.; de Christo Scherer, M.M.; de Oliveira, J.P.; da Silva, A.R.; de Araujo, M.L.; Endringer, D.C.; Fronza, M.; Guimaraes, M.C.C.; Scherer, R. Antioxidant, antimicrobial and cytotoxic activities of gold nanoparticles capped with quercetin. Saudi Pharm. J. 2019, 27, 968–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boomi, P.; Ganesan, R.; Prabu Poorani, G.; Jegatheeswaran, S.; Balakumar, C.; Gurumallesh Prabu, H.; Anand, K.; Marimuthu Prabhu, N.; Jeyakanthan, J.; Saravanan, M. Phyto-Engineered Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) with Potential Antibacterial, Antioxidant, and Wound Healing Activities Under in vitro and in vivo Conditions. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 7553–7568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekar, V.; Al-Ansari, M.M.; Narenkumar, J.; Al-Humaid, L.; Arunkumar, P.; Santhanam, A. Synthesis of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) with improved anti-diabetic, antioxidant and anti-microbial activity from Physalis minima. J. King Saud. Univ. Sci. 2022, 34, 102197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, L.A.; Ferreira, D.M.; Keijok, W.J.; Pinheiro Costa Silva, L.; Romero da Silva, A.; Alves da Silva Filho, E.; Pinto de Oliveira, J.; Cunegundes Guimaraes, M.C. High Antioxidant Activity and Low Toxicity of Gold Nanoparticles Synthesized with Virola Oleífera: An Approach Using Design of Experiments. Res. Sq. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham-Huy, L.A.; He, H.; Pham-Huy, C. Free radicals, antioxidants in disease and health. Int. J. Biomed. Sci. IJBS 2008, 4, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anadozie, S.O.; Adewale, O.B.; Meyer, M.; Davids, H.; Roux, S. In vitro anti-oxidant and cytotoxic activities of gold nanoparticles synthesized from an aqueous extract of the Xylopia aethiopica fruit. Nanotechnology 2021, 32, 315101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vladimirov, G.K.; Sergunova, E.V.; Izmaylov, D.Y.; Vladimirov, Y.A. Chemiluminescent determination of total antioxidant capacity in medicinal plant material. Bull. RSMU 2016, 2, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vladimirov, Y.A.; Proskurnina, E.V. Free radicals and cell chemiluminescence. Biochemistry 2009, 74, 1545–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babakhani, P. The impact of nanoparticle aggregation on their size exclusion during transport in porous media: One- and three-dimensional modelling investigations. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 14071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Femina, C.C.; Kamalesh, T. Advances in stabilization of metallic nanoparticle with biosurfactants- a review on current trends. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvereva, M.V.; Aleksandrova, G.P. Application Potential of Natural Polysaccharides for the Synthesis of Biologically Active Nanobiocomposites (A Review). Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2023, 93, S347–S370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anuradha, K.; Bangal, P.; Madhavendra, S.S. Macromolecular arabinogalactan polysaccharide mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles, characterization and evaluation. Macromol. Res. 2016, 24, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grishchenko, L.A.; Medvedeva, S.A.; Aleksandrova, G.P.; Feoktistova, L.P.; Sapozhnikov, A.N.; Sukhov, B.G.; Trofimov, B.A. Redox reactions of arabinogalactan with silver ions and formation of nanocomposites. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2006, 76, 1111–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesnichaya, M.V.; Zhmurova, A.V.; Sapozhnikov, A.N. Synthesis and Characterization of Water-Soluble Arabinogalactan-Stabilized Bismuth Telluride Nanoparticles. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2021, 91, 1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvereva, Z.; Zhmurova, A.; Shendrik, R. The Use of Spectral Methods for the “Ensemble” Assessment of Synthesis Dynamics of the Arabinogalactan-Stabilized Selenium Nanoparticles. J. Clust. Sci. 2023, 35, 809–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safarpour, F.; Kharaziha, M.; Mokhtari, H.; Emadi, R.; Bakhsheshi-Rad, H.R.; Ramakrishna, S. Kappa-carrageenan based hybrid hydrogel for soft tissue engineering applications. Biomed. Mater. 2023, 18, 055005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvereva, M. The Use of AgNP-Containing Nanocomposites Based on Galactomannan and κ-Carrageenan for the Creation of Hydrogels with Antiradical Activity. Gels 2024, 10, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trofimova, N.N.; Medvedeva, E.N.; Ivanova, N.V.; Malkov, Y.A.; Babkin, V.A. Polysaccharides from Larch Biomass. In The Complex World of Polysaccharides; Pirogov Russian National Research Medical University: Moscow, Russia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Desmarchelier, C.; Repetto, M.; Coussio, J.; Llesuy, S.; Ciccia, G. Total Reactive Antioxidant Potential (TRAP) and Total Antioxidant Reactivity (TAR) of Medicinal Plants Used in Southwest Amazonia (Bolivia and Peru). Int. J. Pharmacogn. 1997, 35, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navas Díaz, A.; García Sanchez, F.; González García, J.A. Hydrogen peroxide assay by using enhanced chemiluminescence of the luminol-H2O2-horseradish peroxidase system: Comparative studies. Anal. Chim. Acta 1996, 327, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, R.; Tang, J.; Swanson, B.G. Water holding capacity and microstructure of gellan gels. Carbohydr. Polym. 2001, 46, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Relation (g/g) HAuCl4/Ar-Gal | Synthesis Time, min | Yield, % | Au, % | Au Conversion, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0047 | 20 | 83 | 0.3 | 100 |

| 0.035 | 35 | 79 | 2.0 | 100 |

| 0.070 | 42 | 71 | 4.3 | 100 |

| 0.17 | 50 | 48.5 | 7.8 | 100 |

| V κCG, mL | V Ar-Gal-AuNPs, mL | V Water, mL | Relation Ar-Gal-AuNPs/κ-CG | CaCl2 mmol | pH | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | - | 7.10 |

| 2 | 2 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.1 | - | 7.08 |

| 3 | 2 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.2 | - | 6.98 |

| 4 | 2 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.3 | - | 7.11 |

| 5 | 2 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.4 | - | 7.0+ |

| 6 | 2 | 1.0 | 0 | 0.5 | - | 6.89 |

| 7 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0.078 | 7.03 |

| 8 | 2 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.078 | 7.00 |

| 9 | 2 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.078 | 7.1 |

| 10 | 2 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.078 | 6.97 |

| 11 | 2 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.078 | 7.00 |

| 12 | 2 | 1.0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.078 | 6.99 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zvereva, M. AuNP-Containing Hydrogels Based on Arabinogalactan and κ-Carrageenan with Antiradical Activity. Gels 2026, 12, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010009

Zvereva M. AuNP-Containing Hydrogels Based on Arabinogalactan and κ-Carrageenan with Antiradical Activity. Gels. 2026; 12(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleZvereva, Marina. 2026. "AuNP-Containing Hydrogels Based on Arabinogalactan and κ-Carrageenan with Antiradical Activity" Gels 12, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010009

APA StyleZvereva, M. (2026). AuNP-Containing Hydrogels Based on Arabinogalactan and κ-Carrageenan with Antiradical Activity. Gels, 12(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010009