A Novel Polyvinyl Alcohol/Salecan Composite Hydrogel Dressing with Tough, Biocompatible, and Antibacterial Properties for Infected Wound Healing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Synthesis of the Composite Hydrogel

2.2. Structural and FTIR Characterization

2.3. Adhesive and Mechanical Properties

2.4. In Vitro Antibacterial Properties

2.5. In Vitro Biocompatibility

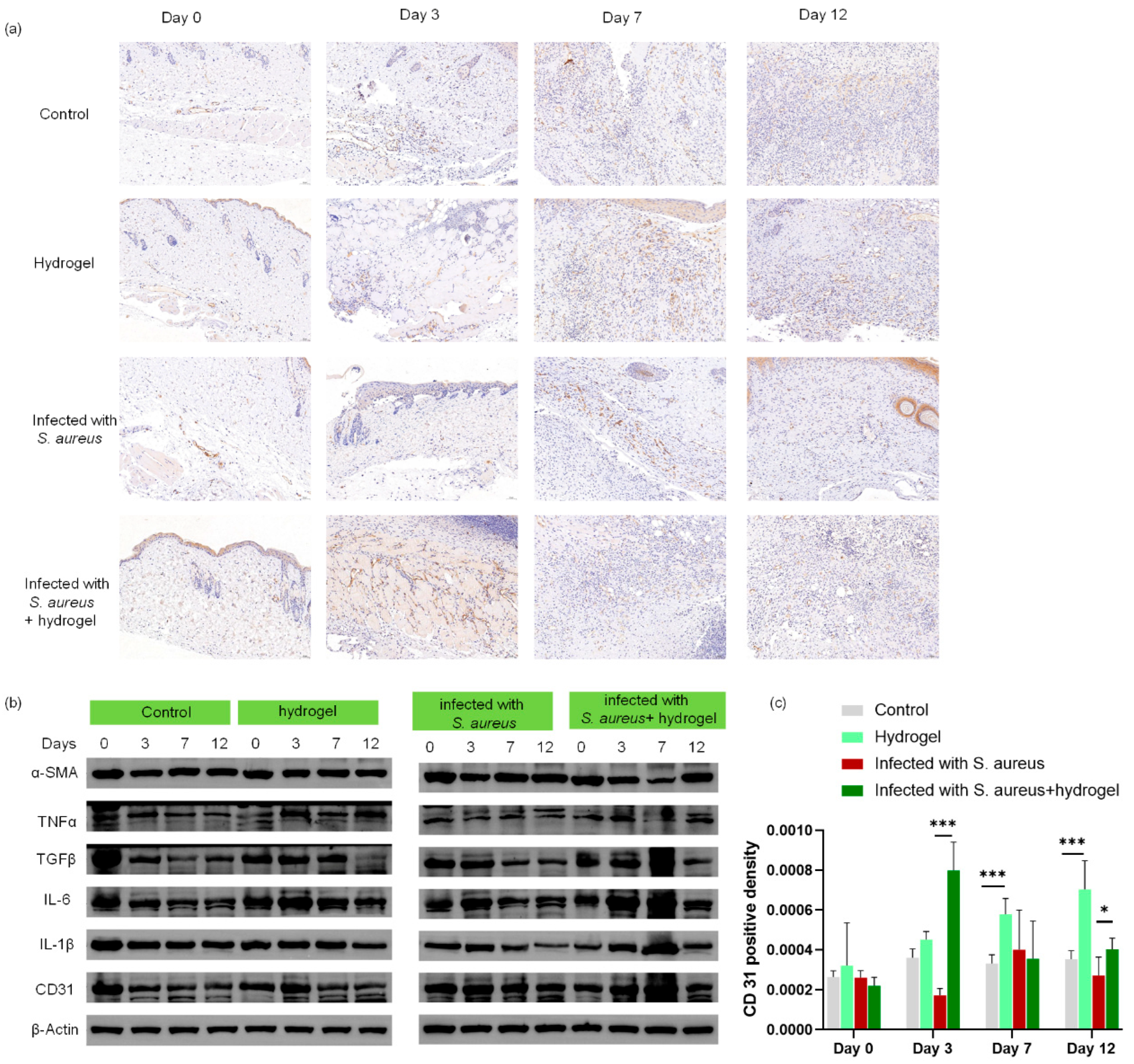

2.6. In Vivo Evaluation of Wound Healing

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Preparation of the Composite Hydrogel

4.3. Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy

4.4. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

4.5. Dynamic Rheological Characterization

4.6. Water Retention Capability

4.7. Swelling Performance

4.8. Mechanics Performance Test

4.9. In Vitro Antibacterial Activity

4.10. Ag+ Release Profile

4.11. Cytocompatibility of the Composite Hydrogel

4.12. In Vivo Infected Wound-Healing Model

4.13. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dong, L.; Han, Z.; Zhang, H.; Yang, R.; Fang, J.; Wang, L.; Li, X.; Li, X. Tea polyphenol/glycerol-treated double-network hydrogel with enhanced mechanical stability and anti-drying, antioxidant and antibacterial properties for accelerating wound healing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 208, 530–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghobril, C.; Grinstaff, M.W. The chemistry and engineering of polymeric hydrogel adhesives for wound closure: A tutorial. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 1820–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Qiu, P.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, L.; Gou, D. Chitosan-based hydrogel wound dressing: From mechanism to applications, a review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 244, 125250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, K.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Fan, X.; Wu, Z.; Wen, X.; Xie, W.; Wang, H.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, P. Phase transition behaviors of poly (N-isopropylacrylamide) nanogels with different compositions induced by (−)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate and ethyl gallate. Molecules 2023, 28, 7823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Q.; Nie, Y.; Xiang, J.; Xie, J.; Si, H.; Li, D.; Zhang, S.; Li, M.; Huang, S. Injectable sodium alginate hydrogel loaded with plant polyphenol-functionalized silver nanoparticles for bacteria-infected wound healing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 234, 123691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiu, A.; Kong, Y.; Zhou, M.; Zhu, B.; Wang, S.; Zhang, J. The chemical and digestive properties of a soluble glucan from Agrobacterium sp. ZX09. Carbohydr. Polym. 2010, 82, 623–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Xu, M. Construction of self-assembled polyelectrolyte complex hydrogel based on oppositely charged polysaccharides for sustained delivery of green tea polyphenols. Food Chem. 2019, 306, 125632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, R.; Li, C.; Yu, C.; Xie, H.; Shi, S.; Li, Z.; Wang, Q.; Lu, L. A novel electrospun membrane based on moxifloxacin hydrochloride/poly(vinyl alcohol)/sodium alginate for antibacterial wound dressings in practical application. Drug Deliv. 2014, 23, 39–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Qi, X.; Li, J.; Zuo, G.; Sheng, W.; Zhang, J.; Dong, W. Smart Macroporous Salecan/Poly(N,N-diethylacrylamide) Semi-IPN Hydrogel for Anti-Inflammatory Drug Delivery. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2016, 2, 1386–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.-C.; Ying, R.; Wang, W.; Guo, Y.; He, Y.; Mo, X.; Xue, C.; Mao, X. A Macroporous Hydrogel Dressing with Enhanced Antibacterial and Anti-Inflammatory Capabilities for Accelerated Wound Healing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 2000644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Xu, M.; Dong, W.; Zhang, J. Fabrication of Salecan/poly(AMPS-co-HMAA) semi-IPN hydrogels for cell adhesion. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 174, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, S.; Wang, D.; Yip, R.C.S.; Xie, W.; Chen, H. Injectable Salecan/hyaluronic acid-based hydrogels with antibacterial, rapid self-healing, pH-responsive and controllable drug release capability for infected wound repair. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 347, 122750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhang, G.; Cheng, P.; Wang, Y.; Fan, X.; Han, J.; Fan, Z. Development of salecan/konjac glucomannan biogels: Insights into advanced rheology, thermal behavior, and model fitting. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 315, 144688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Xu, M.; Zhang, J.; Dong, W. Photopatterned salecan composite hydrogel reinforced with α-Mo2C nanoparticles for cell adhesion. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 199, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, K.; Huang, Q.; Yan, X.; Dai, Y.; Zhao, J.; Xiong, X.; Wang, H.; Chen, X.; Chen, P.; Liu, L. Facile fabrication of a novel, photodetachable salecan-based hydrogel dressing with self-healing, injectable, and antibacterial properties based on metal coordination. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 264, 130551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhail, M.; Shih, C.-M.; Liu, J.-Y.; Hsieh, W.-C.; Lin, Y.-W.; Lin, I.L.; Wu, P.-C. Synthesis of glutamic acid/polyvinyl alcohol based hydrogels for controlled drug release: In-vitro characterization and in-vivo evaluation. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2022, 75, 103715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xu, Y.; Lei, Y.; Wen, X.; Liang, J. Tourmaline nanoparticles modifying hemostatic property of chitosan/polyvinyl alcohol hydrogels. Mater. Lett. 2022, 324, 132718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakkan, T.; Topham, P.D.; Mahomed, A.; Tighe, B.J.; Derry, M.J.; Krasian, T.; Tanadchangsaeng, N.; Srikaew, N.; Somsunan, R.; Jantanasakulwong, K. 2D–2D MoS2/g-C3N4 hybrid-loaded chitosan/PVA hydrogel for controlled curcumin delivery in diabetic wound healing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 330, 148185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, T.; Yan, L.; Wang, B.; Gong, Q.; Wang, G.; Chen, T.; Liu, S.; Wei, H.; He, G.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Preparation and composition analysis of PVA/chitosan/PDA hybrid bioactive multifunctional hydrogel for wound dressing. Eur. Polym. J. 2024, 221, 113527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Xu, A.; Liu, W. Comparative Analysis of Physicochemical Properties and Biocompatibility of Biomass-Derived and Fossil-Derived Polyvinyl Alcohol Hydrogels: Material Screening for Wound Dressing Applications. Gels 2025, 12, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koshy, J.T.; Sangeetha, D. Minocycline Hydrochloride-infused Polyvinyl Alcohol/Pectin-based bio-nanocomposite antibacterial hydrogel films reinforced with nanofibrillar cellulose from biomass for preventing bactericidal infections in wound dressings. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2025, 10, 100831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Fan, D.; Zhu, C.; Duan, Z.; Fu, R.; Li, X. Preparation of physically crosslinked PVA/HLC/SA hydrogel and exploration of its effects on full-thickness skin defects. Int. J. Polym. Mater. Polym. Biomater. 2019, 68, 1048–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Yang, J.; Lin, L.; Peng, K.; Chen, Y.; Jin, S.; Yao, W. Construction of Physically Crosslinked Chitosan/Sodium Alginate/Calcium Ion Double-Network Hydrogel and Its Application to Heavy Metal Ions Removal. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 393, 124728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Ji, J.; Yin, T.; Yang, J.; Pang, Y.; Sun, W. Affinity-Controlled Double-Network Hydrogel Facilitates Long-Term Release of Anti-Human Papillomavirus Protein. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Li, R.; Ao, N.; Zhang, H. A synergy between dopamine and electrostatically bound bactericide in a poly (vinyl alcohol) hybrid hydrogel for treating infected wounds. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 272, 118513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Alcântara, M.G.; de Freitas Ortega, N.; Souza, C.J.F.; Garcia-Rojas, E.E. Electrostatic hydrogels formed by gelatin and carrageenan induced by acidification: Rheological and structural characterization. Food Struct. 2020, 24, 100137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liparoti, S.; Speranza, V.; Marra, F. Alginate hydrogel: The influence of the hardening on the rheological behaviour. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2021, 116, 104341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Jiao, C.; Peng, X.; Liu, T.; Shi, Y.; Liang, M.; Wang, H. Biomimetic anisotropic poly(vinyl alcohol) hydrogels with significantly enhanced mechanical properties by freezing–thawing under drawing†. J. Mater. Chem. B 2019, 7, 3243–4249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, D.; Cui, Y.; Wan, Z.; Wang, S.; Peng, L.; Liao, Z.; Chen, C.; Liu, W. Study on swelling, compression property and degradation stability of PVA composite hydrogels for artificial nucleus pulposus. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2022, 136, 105496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velgosova, O.; Mudra, E.; Vojtko, M. Preparing, Characterization and Anti-Biofilm Activity of Polymer Fibers Doped by Green Synthesized AgNPs. Polymers 2021, 13, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Fu, R.; Duan, Z.; Zhu, C.; Fan, D. Mussel-inspired adhesive bilayer hydrogels for bacteria-infected wound healing via NIR-enhanced nanozyme therapy. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2021, 210, 112230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, D.; Azamthulla, M.; Santhosh, S.; Dath, G.; Ghosh, A.; Natholia, R.; Anbu, J.; Teja, B.V.; Muzammil, K.M. Development and characterization of chitosan-based hydrogels as wound dressing materials. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2018, 46, 498–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Huang, J.; Wu, X.; Ren, Y.; Li, Z.; Ren, J. Controlled release of silver ions from AgNPs using a hydrogel based on konjac glucomannan and chitosan for infected wounds. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 149, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Hu, X.; Wei, W.; Yu, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Dong, W. Investigation of Salecan/poly(vinyl alcohol) hydrogels prepared by freeze/thaw method. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 118, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Wei, W.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Hu, X.; Zhang, J.; Bi, L.; Dong, W. Fabrication and Characterization of a Novel Anticancer Drug Delivery System: Salecan/Poly(methacrylic acid) Semi-interpenetrating Polymer Network Hydrogel. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2015, 1, 1287–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajati, H.; Alvandi, H.; Rahmatabadi, S.S.; Hosseinzadeh, L.; Arkan, E. A nanofiber-hydrogel composite from green synthesized AgNPs embedded to PEBAX/PVA hydrogel and PA/Pistacia atlantica gum nanofiber for wound dressing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 226, 1426–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, L.; Tang, K. Highly stretchable and adhesive hydrogel dressing possessing rapid hemostasis and photothermal antibacterial properties for joint wound healing. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 519, 164834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Hui, F.; Tian, T.; Yan, R.; Xin, J.; Zhao, X.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Kuang, Y.; Li, N.; et al. A Novel Conductive Antibacterial Nanocomposite Hydrogel Dressing for Healing of Severely Infected Wounds. Front. Chem. 2021, 9, 787886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Akter, N.; Rahman, M.M.; Shi, C.; Islam, M.T.; Zeng, H.; Azam, M.S. Mussel-Inspired Immobilization of Silver Nanoparticles toward Antimicrobial Cellulose Paper. Acs Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 9178–9188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, T.; Zhang, L.; Chen, P.; Tang, S.; Chen, A.; Li, M.; Peng, G.; Gao, H.; Weng, H.; et al. Combination of lyophilized adipose-derived stem cell concentrated conditioned medium and polysaccharide hydrogel in the inhibition of hypertrophic scarring. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 12, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Peng, S.; Yao, Y.; Xie, J.; Li, S.; Tu, C.; Gao, C. A nanofibrous membrane loaded with doxycycline and printed with conductive hydrogel strips promotes diabetic wound healing in vivo. Acta Biomater. 2022, 152, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Sun, Y.; Wang, J.; Kang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Cao, W.; Ye, J.; Gao, C. A tough, antibacterial and antioxidant hydrogel dressing accelerates wound healing and suppresses hypertrophic scar formation in infected wounds. Bioact. Mater. 2024, 34, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jatoi, A.W.; Ogasawara, H.; Kim, I.S.; Ni, Q.-Q. Dopa-based facile procedure to synthesize AgNP/cellulose nanofiber composite for antibacterial applications. Appl. Nanosci. 2019, 9, 1661–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Hu, X.; Qi, X.; Yu, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Dong, W. A novel thermo-responsive hydrogel based on salecan and poly(N-isopropylacrylamide): Synthesis and characterization. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2014, 125, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, X.; Li, Z.; Shen, L.; Qin, T.; Qian, Y.; Zhao, S.; Liu, M.; Zeng, Q.; Shen, J. Highly efficient dye decontamination via microbial salecan polysaccharide-based gels. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 219, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Yan, L.; Xu, M.; Tang, L. Photo-degradable salecan/xanthan gum ionic gel induced by iron (III) coordination for organic dye decontamination. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 238, 124132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Wang, J.; Li, L.; Xu, L.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Fei, X.; Tian, J.; Li, Y. A novel high-strength poly(ionic liquid)/PVA hydrogel dressing for antibacterial applications. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 365, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskandarinia, A.; Gharakhloo, M.; Kermani, P.K.; Navid, S.; Salami, M.A.; Khodabakhshi, D.; Samadi, A. Antibacterial self-healing bilayer dressing for epidermal sensors and accelerate wound repair. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 319, 121171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, R.; Qin, X.; Yuan, P.; Lei, K.; Wang, L.; Bai, Y.; Liu, S.; Chen, X. Fabrication of Self-Healing Hydrogels with On-Demand Antimicrobial Activity and Sustained Biomolecule Release for Infected Skin Regeneration. Acs Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 17018–17027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Lin, J.; Tao, X.; Qu, J.; Liao, S.; Li, M.; Deng, K.; Du, P.; Liu, K.; Thissen, H. Harnessing colloidal self-assembled patterns (cSAPs) to regulate bacterial and human stem cell response at biointerfaces in vitro and in vivo. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 20982–20994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klopfenstein, N.; Cassat, J.E.; Monteith, A.; Miller, A.; Drury, S.; Skaar, E.; Serezani, C.H. Murine Models for Staphylococcal Infection. Curr. Protoc. 2021, 1, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, W.; Zhou, X.; Tu, C.; Wang, Z.; Liu, X.; Kang, Y.; Wang, J.; Deng, L.; Zhou, T.; Gao, C. A broad-spectrum antibacterial and tough hydrogel dressing accelerates healing of infected wound in vivo. Biomater. Adv. 2022, 145, 213244. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, J.; Li, C.; Zhang, Q.; Rao, Z.; Meng, Q.; Li, M.; Dai, J.; Deng, K.; Chen, P. A Novel Polyvinyl Alcohol/Salecan Composite Hydrogel Dressing with Tough, Biocompatible, and Antibacterial Properties for Infected Wound Healing. Gels 2026, 12, 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010060

Li J, Li C, Zhang Q, Rao Z, Meng Q, Li M, Dai J, Deng K, Chen P. A Novel Polyvinyl Alcohol/Salecan Composite Hydrogel Dressing with Tough, Biocompatible, and Antibacterial Properties for Infected Wound Healing. Gels. 2026; 12(1):60. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010060

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Jiayu, Can Li, Qi Zhang, Zhenhao Rao, Qinghuan Meng, Miao Li, Juan Dai, Ke Deng, and Pengfei Chen. 2026. "A Novel Polyvinyl Alcohol/Salecan Composite Hydrogel Dressing with Tough, Biocompatible, and Antibacterial Properties for Infected Wound Healing" Gels 12, no. 1: 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010060

APA StyleLi, J., Li, C., Zhang, Q., Rao, Z., Meng, Q., Li, M., Dai, J., Deng, K., & Chen, P. (2026). A Novel Polyvinyl Alcohol/Salecan Composite Hydrogel Dressing with Tough, Biocompatible, and Antibacterial Properties for Infected Wound Healing. Gels, 12(1), 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels12010060